Oleotourism: Local Actors for Local Tourism Development

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Sustainability and Territory

2.2. Agritourism

2.3. Oleotourism

3. Methodology

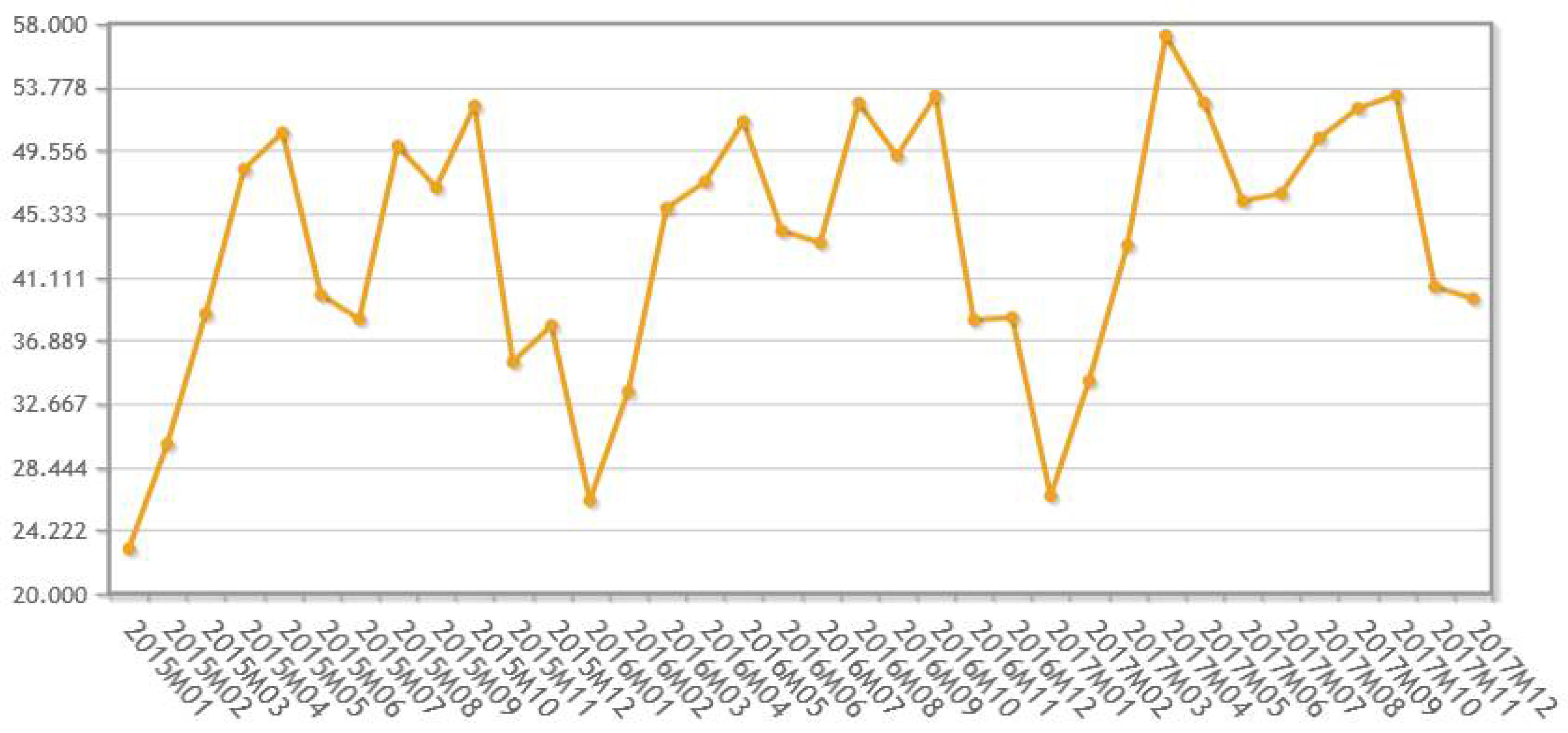

3.1. Research Context: Current Situation in Jaén

3.2. Aim and Research Process

4. Results

4.1. Involvement in Oleotourism

“There are tourists who come here and ask if you can do a tasting or if you can visit an oil mill; we have some flyers and brochures and we also answer that the tourism office in the old town has a lot of information about oil tourism.”(Interviewee n.6)

“Some tourists arrive at the restaurant and ask for an olive oil tasting session, but I am forced to state that I can’t because I need to plan it and fit it in with the guests we have at the restaurant. Mills should deliver the inquiry before; I can’t stop serving guests for a tasting session.”

“We have many requests to belong to the ‘Oleotour Program’, but when we tell them the requirements for example of mill, spa, singular accommodations, restaurants ... the people back out, but there are requests.”

4.2. Sustainability

“I made visits to the field because people wanted to see the olive harvest, you go, but without bothering the workers explaining what they are doing…”.(Interviewee n.7)

“…the real problem is sightseeing when there are no olives during the year. In these cases, frozen olives are used to make tourism activities.”(Interviewee n.5)

“When it is time to harvest, lots of people are attracted and come to the field to observe. They are attracted by the beauty of the field, with a unique view consisting of millions of olive trees. They enjoy experiencing both the activities and the physical context.”(Interviewee n.3)

“What is most requested is the visit to the mill and of course there is a relationship between the quality of the olive oil and the activities of oleotourism. For example, one of the parts of the quality of the oil is that the mill is clean, if it is not clean it has no quality.”(Interviewee n.1)

“The sustainability of these oleotourism activities is also guaranteed by new hired employees, as Picualia [an olive oil mill] has done in recent months.”.(Interviewee n.5)

4.3. Opportunities

“Olive oil is a healthy product that suits all kinds of products, almost like water, with sweet and salty ...”(Interviewee n.2)

“Foreign tourists are increasingly aware of the healthful properties of this product.”(Interviewee n.9)

“The facilities are new; the Diputación de Jaén financed the work. We have also adapted the area of the office with a section of exhibition and sale or for example we have enabled the upper part to make the tastings.”(Interviewee n.8)

“From 2013 until today, we want to end this stage with the formalization of a product club; a product club is, in rough outlines, to leave the subject at the hands of the entrepreneurs, create a kind of partnership and that among all they commercialize. We are in this stage right now.”

“Tourists visiting the Southern Coast—the Costa del Sol—move to Ubeda and Baeza due to their being part of the World Heritage List, while olive oil is just a possible complement; my outlook is that of an interesting market.”

4.4. Constraints

“Politics should encourage a little more; here, for example, the Diputación de Jaén is quite active, but the Junta de Andalucía and the City Council do almost nothing and Jaén does not have such an important position in the thoughts of the Junta de Andalucía. This cannot stand because the city has many attractions, the Cathedral, the Arab Baths, and then it would be quite simple to attract tourists here.”(Interviewee n.6)

“For example, you go to an oil mill and only have accident insurance during the harvesting season, and to do oleotourism actions you need to have insurance throughout the year. Or, for example, the law of data protection, the access for the disabled, or the information about the activities related to oleotourism, besides being open both summer and weekends.”

“There are mills making the decision to perform activities to introduce oleotourism, but they did not invest a single euro. This negatively affected the efforts performed by the other mills that opted to hire professionals and implement new services. When tourists visit mills with old machines, dirty areas, and without a guided tour in their own language, nor with the basic services needed, tourists have and spread a negative perception of oleotourism.”

“In these years, we have verified that those olive oil mills that have hired a tourism technician are the ones that are working properly. And those olive oil mills in which the staff is prepared with languages and that know how to make a visit are working better. I believe that the training of workers is fundamental. “

5. Discussion and Implications

6. Conclusions

7. Limitation and Further Research

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations. Measuring Sustainable Tourism: A Call for Action. 2017. Available online: https://www.e-unwto.org/doi/pdf/10.18111/9789284418954 (accessed on 29 March 2018).

- International Union for Conservation of Nature. A Step to Sustainability. 2017. Available online: http://www.iucn.org/news/commission-environmental-economic-and-social-policy/201702/step-sustainability-maes-mapping-and-assessment-ecosystem-services-european-cities-and-italy (accessed on 29 March 2018).

- Fien, J.; Calder, M.; White, C. Sustainable Tourism. 2011. Teaching and Learning for a Sustainable Future—UNESCO. Available online: http://www.unesco.org/education/tlsf/mods/theme_c/mod16.html (accessed on 29 March 2018).

- World Farmers’ Organization. From Farm to Fork—Agri-Tourism. 2017. Available online: http://www.wfo-oma.org/news/from-farm-to-fork-agri-tourism-the-potential-of-the-international-year-of-sustainable-tourism.html (accessed on 29 March 2018).

- World Tourism Organization. Tourism and the Sustainable Development Goals. 2015. Available online: https://www.e-unwto.org/doi/pdf/10.18111/9789284417254 (accessed on 29 March 2018).

- World Tourism Organization. Managing Growth and Sustainability in Tourism. 2017. Available online: https://www.e-unwto.org/doi/book/10.18111/9789284418909 (accessed on 29 March 2018).

- Cawley, M.; Gillmor, D.A. Integrated rural tourism: Concepts and Practice. Ann. Tour. Res. 2008, 35, 316–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McComb, E.J.; Boyd, S.; Boluk, K. Stakeholder collaboration: A means to the success of rural tourism destinations? A critical evaluation of the existence of stakeholder collaboration within the Mournes, Northern Ireland. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2017, 17, 286–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addinsall, C.; Scherrer, P.; Weiler, B.; Glencross, K. An ecologically and socially inclusive model of agritourism to support smallholder livelihoods in the South Pacific. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2017, 22, 301–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Despotović, A.; Joksimović, M.; Svržnjak, K.; Jovanović, M. Rural areas sustainability: Agricultural diversification and opportunities for agri-tourism development. Transcult. Stud. 2017, 63, 47–62. [Google Scholar]

- Morales, P.M.C.; Guzmán, T.J.L.-G.; Cuadra, S.M.; Agüera, F.O. Análisis de la demanda del oleoturismo en Andalucía/Analysis of demand of olive tourism in Andalusia. Rev. Estud. Reg. 2015, 104, 133. [Google Scholar]

- Millán, M.G.; Pablo-Romero, M.D.P.; Sánchez-Rivas, J. Oleotourism as a Sustainable Product: An Analysis of Its Demand in the South of Spain (Andalusia). Sustainability 2018, 10, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millán, G.; Arjona, J.M.; Amador, L. A new market segment for olive oil: Olive oil tourism in the south of Spain. Agric. Sci. 2014, 5, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carley, M.; Christie, I. Managing Sustainable Development; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Berque, A. Médiance: De milieux en paysages; Reclus: Montpellier, France, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Rees, J. Natural Resources: Allocation, Economics and Policy; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Clifford, S. Local distinctiveness: Everyday places and how to find them. In Local Heritage, Global Context; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2016; pp. 31–50. [Google Scholar]

- Camagni, R. Regional competitiveness: Towards a concept of territorial capital. In Seminal Studies in Regional and Urban Economics; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 115–131. [Google Scholar]

- Vivian, J.M. Foundations for sustainable development: Participation, empowerment and local resource management. In Grassroots Environmental Action; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2014; pp. 66–94. [Google Scholar]

- Brundtland, G.H. Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development: “Our Common Future”; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Sansone, M.; Tartaglione, M.A.; Bruni, R. Enterprise—Place relationship and value co-creation: Advance in Research. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2015, 10, 50–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruni, R.; Caboni, F. Place as Value Proposition: The Marketing Perspective; FrancoAngeli: Milano, Italy, 2017; ISBN 9788891761484. [Google Scholar]

- Guzmán, P.C.; Roders, A.P.; Colenbrander, B.J.F. Measuring links between cultural heritage management and sustainable urban development: An overview of global monitoring tools. Cities 2017, 60, 192–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coccossis, H. Sustainable development and tourism: Opportunities and threats to cultural heritage6from tourism. In Cultural Tourism and Sustainable Local Development; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2016; pp. 65–74. [Google Scholar]

- Coccossis, H. Sustainable tourism and carrying capacity: A new context. In The Challenge of Tourism Carrying Capacity Assessment; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2017; pp. 19–30. [Google Scholar]

- Mowforth, M.; Munt, I. Tourism and Sustainability: Development, Globalisation and New Tourism in the Third World; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Charters, S.; Spielmann, N. Characteristics of strong territorial brands: The case of champagne. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 1461–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarabia-Sanchez, F.J.; Cerda-Bertomeu, M.J. Place brand developers’ perceptions of brand identity, brand architecture and neutrality in place brand development. Place Brand. Public Dipl. 2017, 13, 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trono, A.; Ruppi, F.; Mitrotti, F.; Cortese, S. The Via Francigena Salentina as an Opportunity for Experiential Tourism and a Territorial Enhancement Tool. Almatourism 2017, 8, 20–41. [Google Scholar]

- Armesto López, X.A.; Martín, B.G. Productos agroalimentarios de calidad y turismo en España: Estrategias para el desarrollo local. Geographicalia 2005, 47, 87–110. [Google Scholar]

- Chase, L.C.; Amsden, B.; Phillips, R.G. Stakeholder engagement in tourism planning and development. In Handbook of Tourism and Quality-of-Life Research; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 475–490. [Google Scholar]

- Millán Vázquez de la Torre, G.; Caridad y Ocerín, J.; Arjona Fuentes, J.M.; Amador Hidalgo, L. Tequila tourism as a factor of development: A strategic vision in Mexico. Tour. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 20, 137–149. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, T.C. Agriculture tourism and the transformation of rural countryside. Tour. Geogr. 2018, 20, 354–357. [Google Scholar]

- Gil Arroyo, C.; Barbieri, C.; Rich, S.R. Defining agritourism: A comparative study of stakeholders’ perceptions in Missouri and North Carolina. Tour. Manag. 2013, 37, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leco, F.; Hernández, J.M.; Campón, A.M. Rural tourists and their attitudes and motivations towards the practice of environmental activities such as agrotourism. Int. J. Environ. Res. 2013, 7, 255–264. [Google Scholar]

- Coriglian, M.A. Wine routes and territorial events as enhancers of tourism experiences. In Wine and Tourism; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 41–56. [Google Scholar]

- Tourism Satellite Account. Recommended Methodological Framework, Eurostat, OECD, WTO, UNSD. 2001. Available online: http://stats.oecd.org (accessed on 29 March 2018).

- Croce, E.; Perri, G. Food and Wine Tourism; Cabi: Wallingford, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Maetzold, J.A. Nature-Based Tourism and Agritourism Trends: Unlimited Opportunities. 2002. Available online: https://www.agmrc.org/media/cms/agritourism_E6794269B3FF6.pdf (accessed on 29 March 2018).

- Galati, A.; Siggia, D.; Crescimanno, M.; Martín-Alcalde, E.; Saurí Marchán, S.; Morales-Fusco, P. Competitiveness of short sea shipping: The case of olive oil industry. Br. Food J. 2016, 118, 1914–1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souilem, S.; El-Abbassi, A.; Kiai, H.; Hafidi, A.; Sayadi, S.; Galanakis, C.M. Olive oil production sector: Environmental effects and sustainability challenges. In Olive Mill Waste; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017; pp. 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Duarte Alonso, A. Olives, hospitality and tourism: A Western Australian perspective. Br. Food J. 2010, 112, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, G. Gastronomy: An essential ingredient in tourism production and consumption. Tour. Gastron. 2002, 11, 2–20. [Google Scholar]

- Corigliano, M.A.; Baggio, R. Italian culinary tourism on the Internet. Gastron. Tour. 2002, 92–106. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, L.; Hall, D.; Morag, M. (Eds.) New Directions in Rural Tourism; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bramwell, B.; Lane, B. (Eds.) Tourism Collaboration and Partnerships: Politics, Practice and Sustainability; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2000; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Loumou, A.; Giourga, C. Olive groves: The life and identity of the Mediterranean. Agric. Hum. Values 2003, 20, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flanigan, S.; Blackstock, K.; Hunter, C. Generating public and private benefits through understanding what drives different types of agritourism. J. Rural Stud. 2015, 41, 129–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millán Vázquez de la Torre, G.; Pérez, L.M. Comparación del perfil de enoturistas y oleoturistas en España. Un estudio de caso. Cuadernos de Desarrollo Rural 2014, 11, 167–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, R.; Awais, M. Rural Tourism: An Emerging Paradigm in Rural Entrepreneurship. Adhyayan 2016, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karray, B. Olive oil world market dynamics and policy reforms: Implications for Tunisia. In Proceedings of the 98th Seminar of the EAAE, Chania, Greece, 29 June–2 July 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Duarte Alonso, A.; Northcote, J. The development of olive tourism in Western Australia: A case study of an emerging tourism industry. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2010, 12, 696–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, T.D.; Mossberg, L.; Therkelsen, A. Food and tourism synergies: Perspectives on consumption, production and destination development. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2017, 17, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlontzos, G. Greek Olive Oil: How Can Its International Market Potential Be Realized? Estey Cent. J. Int. Law Trade Policy 2008, 9, 32. [Google Scholar]

- Engeset, A.B.; Heggem, R. Strategies in Norwegian farm tourism: Product development, challenges, and solutions. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2015, 15, 122–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paddock, J.; Marsden, T. Revisiting evolving webs of agri-food and rural development in the UK: The case of Devon and Shetland. In Constructing a New Framework for Rural Development; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2015; pp. 301–324. [Google Scholar]

- Dias, C.; Franco, M. Cooperation in tradition or tradition in cooperation? Networks of agricultural entrepreneurs. Land Use Policy 2018, 71, 36–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kizos, T.; Vakoufaris, H. Valorisation of a local asset: The case of olive oil on Lesvos Island, Greece. Food Policy 2011, 36, 705–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagaria, C.; Schulp, C.J.; Kizos, T.; Verburg, P.H. Perspectives of farmers and tourists on agricultural abandonment in east Lesvos, Greece. Reg. Environ. Chang. 2018, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murgado Armenteros, E.M. Turning food into a gastronomic experience: Olive oil tourism. Options Mediterr. 2013, 106, 97–109. [Google Scholar]

- Murgado Armenteros, E.M.; Ruíz, F.J.T.; Rosa, M.P.; Zamora, M.V. El aceite de oliva como elemento nuclear para el desarrollo del turismo. In Turismo Gastronómico: Estrategias de Marketing y Experiencias de éxito; Universidad de Zaragoza: Zaragoza, Spain, 2011; pp. 191–220. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez-Beltrán, F.J.; López-Guzmán, T.; González Santa Cruz, F. Analysis of the relationship between tourism and food culture. Sustainability 2016, 8, 418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tudisca, S.; Di Trapani, A.M.; Donia, E.; Sgroi, F.; Testa, R. The market reorientation of farms: The case of olive growing in the Nebrodi area. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2015, 21, 179–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez Cohard, J.C.R.; Parras Rosa, M.P. Los canales de comercialización de los aceites de oliva españoles. Cuad. Estud. Agroaliment. 2012, 4, 93–102. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz Guerra, I.R.; López, V.M.M.; Moreno, V.M. Olive Oil intangibility for competitive advantage. Intang. Cap. 2012, 8, 150–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Areal, F.J.; Riesgo, L. Farmers’ views on the future of olive farming in Andalusia, Spain. Land Use Policy 2014, 36, 543–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zambrana Pineda, J.F. Los cambios en el mercado mundial de los aceites vegetales y las transformaciones en el olivar y en los aceites de oliva españoles, 1940–2009. Historia Agraria Revista de Agricultura e Historia Rural 2015, 67, 111–141. [Google Scholar]

- Martín Mesa, A.; Duro Cobo, J.J.; Alcalá Olid, F. Observatorio Económico de la Provincia de Jaén, Nº 202. Septiembre 2013. Available online: https://www.dipujaen.es/export/observatorio_economico/Numero202.pdf (accessed on 29 March 2018).

- D’Auria, A.; Tregua, M.; Marano-Marcolini, C. Setting up an empirical research on OleoTourism. In Proceedings of the Comunicaciones Científicas XVIII Simposium Expoliva, Jaén, Spain, 10–12 May 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Parra-López, C.; Hinojosa-Rodríguez, A.; Sayadi, S.; Carmona-Torres, C. Protected Designation of Origin as a Certified Quality System in the Andalusian olive oil industry: Adoption factors and management practices. Food Control 2015, 51, 321–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tew, C.; Barbieri, C. The perceived benefits of agritourism: The provider’s perspective. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, L.E. La mirada cualitativa en sociología: Una Aproximación Interpretativa; Fundamentos: Madrid, Spain, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Tosun, C. Expected nature of community participation in tourism development. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 493–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haven-Tang, C.; Jones, E.; Webb, C. Critical success factors for business tourism destinations: Exploiting Cardiff’s national capital city status and shaping its business tourism offer. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2007, 22, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, S.; Miller, G.A. The responsible marketing of tourism: the case of Canadian Mountain Holidays. Tour. Manag. 2005, 26, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, A.; Corbin, J.M. Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory Procedures and Techniques; Sage Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Mili, S. Market dynamics and policy reforms in the EU olive oil industry: An exploratory assessment. In Proceedings of the 98th EAAE Seminar ‘Marketing Dynamics within the Global Trading System: New Perspectives’, Chania, Greece, 29 June–2 July 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Senise Barrio, O.; Torres Ruiz, F.J.; Parras Rosa, M.; Murgado Armenteros, E.M. Factors that encourage environmentally sustainable behaviour: The case of olive oil cooperatives in the province of Jaén [Spain]. Revista de Economía Pública, Social y Cooperativa 2008. [Google Scholar]

| Estimation of Olive Oil Production 2017/2018 | (tons) |

|---|---|

| World | 2,854,000 |

| Spain | 1,150,000 |

| Andalusia | 884,900 |

| Province | Olive Production (.000 tons) | Olive oil Production (.000 tons) | Olive Oil, Comparison with the Last 5 Years (%) | Olive Oil, Comparison with Previous Year (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Almeria | 62.8 | 12.5 | 15.8 | 12.2 |

| Cádiz | 46.9 | 8.7 | −3.3 | −15.8 |

| Cordoba | 1,244.2 | 243.7 | 1.4 | −8.9 |

| Granada | 400 | 91.4 | −13.1 | −15.8 |

| Huelva | 37.7 | 7.2 | 23.2 | −1 |

| Jaén | 1,651 | 360 | −16.5 | −28.5 |

| Malaga | 295.6 | 57.7 | −4.9 | 23.2 |

| Sevilla | 564.3 | 103.7 | 8.6 | 7.7 |

| Andalusia | 4,302.5 | 884.9 | −7.7 | −15.8 |

| Province | Arrivals | % var | % | Nights Spent | % var | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Almeria | 1,715,058 | 4.1 | 7.8 | 7,039,661 | 2.5 | 10.3 |

| Cadiz | 3,045,976 | 5.5 | 13.8 | 9,369,993 | 5.4 | 13.7 |

| Cordoba | 1,364,170 | 47 | 6.2 | 2,304,153 | 4.1 | 3.4 |

| Granada | 3,140,759 | −1.9 | 14.2 | 6,859,161 | 0.2 | 10.05 |

| Huelva | 1,292,807 | 0.8 | 5.9 | 5,113,960 | 3.8 | 7.5 |

| Jaén | 683,172 | 4.1 | 3.1 | 1,342,091 | 5.8 | 2.0 |

| Malaga | 6,978,447 | 5.3 | 31.6 | 28,631,295 | 2.9 | 42.0 |

| Sevilla | 3,837,536 | 7.2 | 17.4 | 7,541,063 | 7.0 | 11.05 |

| Andalucia | 22,057,925 | 4.1 | 100.0 | 68,201,377 | 3.5 | 100.0 |

| Interviewee | Industry/Main Activity | PROFILE/ROLE |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Local governmental agency | Chief of the tourism services area |

| 2 | Olive oil museum | Director |

| 3 | Tourism and travel agency | Manager |

| 4 | Restaurant | Owner |

| 5 | Education | Academic/researcher |

| 6 | Hotel | Guest relation manager |

| 7 | Mill | Responsible for oleotourism |

| 8 | Mill | Responsible for oleotourism |

| 9 | Non-profit organization to promote olive oil | Manager |

| Main Issues | Tied Literature |

|---|---|

| Compatibility: | - Loumou and Giourga (2003): the activities take place in different parts of the year |

| Can oleotourism and farming co-exist and take place at the same time in the same place? Are there environmental sustainability issues? | - Millán Vázquez de la Torre et al. (2014): trees and surrounding areas can be damaged |

| Relationships among actors: | - Duarte Alonso (2010): relationships are expected only in fairs and operators know how to expand their core business |

| How do relationships between farmers and operators from other industries affect oleotourism? Should the extant relationships be further empowered? | - Kizos and Vakoufaris (2011): farmers are willing to further develop linkages with other actors |

| Mutual support: | - Karray (2008): hospitality can favor the olive oil industry |

| Can the linkages between olive oil industry and tourism companies be mutually supportive? | - Duarte Alonso and Northcote (2010): tourism can benefit from the olive oil industry |

| Further investments to be done in infrastructures: | - Millán Vázquez de la Torre et al. (2014): safety standards, new structures to host visitors and personnel to be hired |

| Are farmers worried about the need to further invest money to achieve suitable conditions to offer touristic activities? | - Trono et al. (2017): investments are needed to create a good reputation and acquire a multidisciplinary approach |

| Tourists’ involvement and participation: | - Leco et al. (2013): rural life is something attracting tourists’ attention and leading them to live it as a personal experience |

| Are there activities tourists are already doing or willing to do in olive groves landscape? | - Tudisca et al. (2015): tourists are willing to participate in harvesting |

| Conditions emerging from the market: | - Mili (2006): trends are positive and can be further developed |

| Is there an increasing trend in oleotourism? How is this development taking place? | - Cañero Morales et al. (2015) highlighted the need to further investigate and develop a new and appealing typology of tourism, as oleotourism is |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tregua, M.; D’Auria, A.; Marano-Marcolini, C. Oleotourism: Local Actors for Local Tourism Development. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1492. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10051492

Tregua M, D’Auria A, Marano-Marcolini C. Oleotourism: Local Actors for Local Tourism Development. Sustainability. 2018; 10(5):1492. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10051492

Chicago/Turabian StyleTregua, Marco, Anna D’Auria, and Carla Marano-Marcolini. 2018. "Oleotourism: Local Actors for Local Tourism Development" Sustainability 10, no. 5: 1492. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10051492

APA StyleTregua, M., D’Auria, A., & Marano-Marcolini, C. (2018). Oleotourism: Local Actors for Local Tourism Development. Sustainability, 10(5), 1492. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10051492