Bottom-Up Energy Transition Narratives: Linking the Global with the Local? A Comparison of Three German Renewable Co-Ops

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. A Framework to Analyze Energy Transition Narratives

2.1. Actors’ Roles and Bottom-Up Energy Transition Narratives

2.1.1. Innovators

2.1.2. Adopters

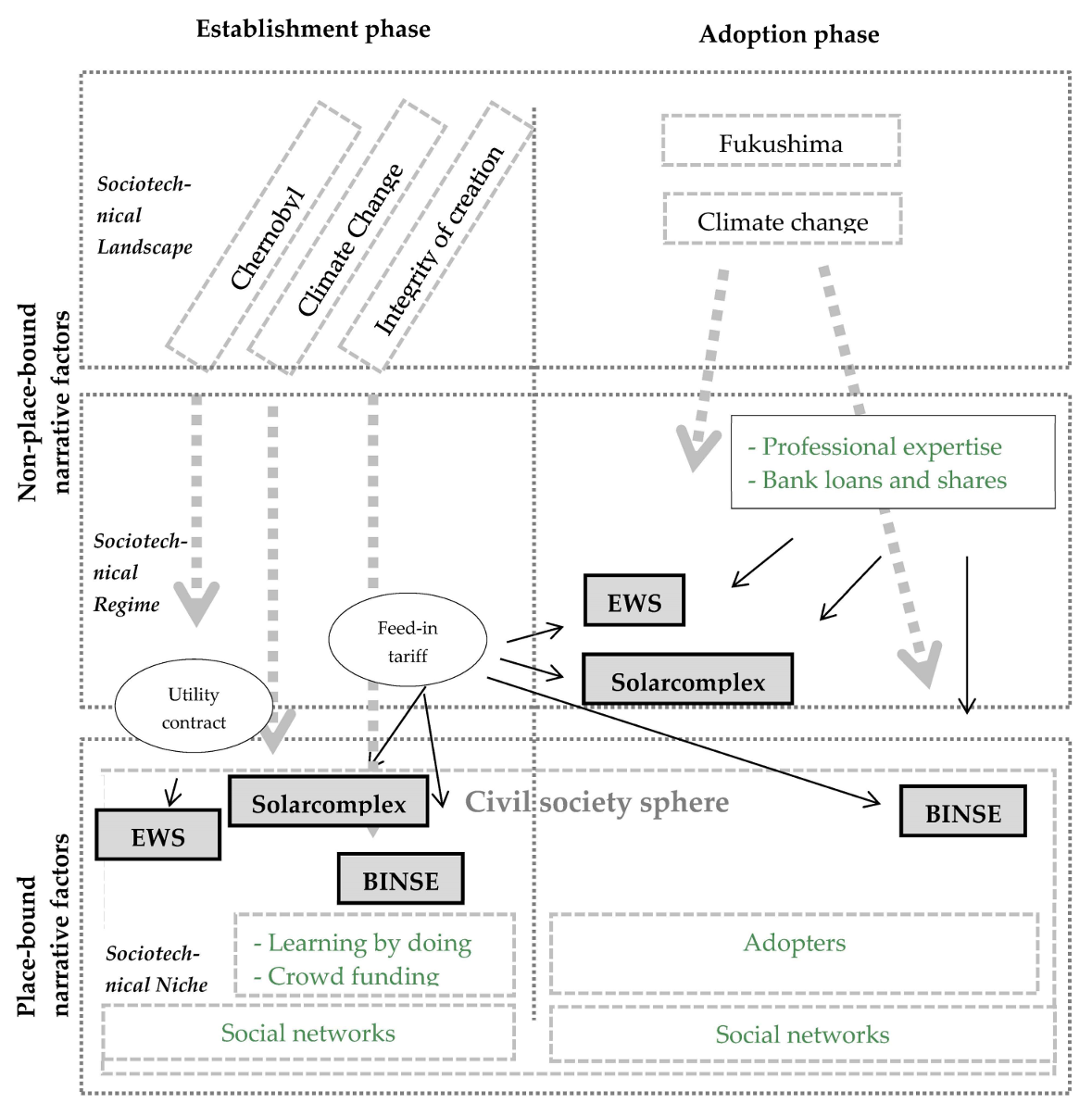

2.2. Spatial Dimensions of Bottom-Up Energy Transition Narratives

2.2.1. Non Place-Bound Factors

2.2.2. Place-Bound Factors

2.3. Interdiscursivity

3. Method

3.1. Sources

3.2. Procedure

4. Analyzing Energy Transition Narratives

4.1. Bottom-Up Energy Transition Narratives during the Establishment Phase

4.1.1. Case Briefings: Establishment Phase

- EWS. In 1988 the association Parents for Nuclear-Free Future (EfaZ; German: Eltern für atomfreie Zukunft) [50] was founded in Schönau, a city located in the South German Black Forest region in the state of Baden-Württemberg. In 1990, after a locally initiated energy saving campaign, EfaZ began articulating ambitions in the local council to repurchase the local electricity grid from the local electricity utility, since the utility’s contract with Schönau was about to expire and since this would allow them to later design tariffs (interviews 16, 38). A local debate evolved over the question of whether a citizen’s initiative or a professionalized firm should operate the Schönau grid (interview 17). After campaigning and two local referendums (1991 and 1996) [38], the people of Schönau voted for the experiment with the new energy initiative. The newly founded company began organizing the takeover of the grid in 1997 with Elektrizitätswerke Schönau Ltd. after a nationwide crowdfunding campaign. This ultimately brought EWS to a larger audience in Germany, spreading the success story of Schönau [38].

- Solarcomplex. Located within the Konstanz district and close to Lake Constance in the state of Baden-Württemberg, a group of sustainability-oriented people met every week in Singen Workshops (German: Singener Werkstätten), to debate issues of sustainability in light of the Agenda 21 process that was underway at that time [32] (Agenda 21 is an action program designed by the United Nations to foster sustainable development in the 21st century. The program was agreed upon in Rio de Janeiro in 1992 and aims also at community action). Soon a firm was founded which operated less confrontationally than EWS and started as a crowd-funding initiative that promoted solar roof panels. From the beginning, Solarcomplex launched public campaigns using the narrative of citizens’ participation and professionally printed brochures to inform citizens of the Western Lake Constance region about their idea to turn the region into a 100-percent renewable energy region. Further, Solarcomplex incorporated clear benchmarking goals, and internal hands-on learning processes helped to adapt the adoption pathways of renewable energy technologies as needed. This included photovoltaic system, hydro power and bioenergy generation for heating (wood and biogas) [51].

- BINSE. Initially, the motivation to set up BINSE in Berchum was the enthusiasm for photovoltaic technologies of its founder. Berchum is a district of Hagen, a city which is located in the state of North Rhine-Westphalia. In 2002, the installation of a community photovoltaic unit on the rooftop of the youth education center of the local Protestant church was successfully realized [38]. This marked the start of a close cooperation with local churches that would soon become a successful operational model. The project’s success was not only due to the cooperation with the church, it was also due to the cooperation of citizens who gave loans for investments (interview 3).

4.1.2. Non-Place-Bound Narrative Factors

4.1.3. Place-Bound Narrative Factors

4.1.4. Intermediate Results

4.2. Bottom-Up Energy Transition Narratives during the Adoption Process

4.2.1. Case Briefings: Adoption phase

- EWS. From 1999, after the liberalization of the German electricity market (due to EG directive 96/92), EWS’s next step was to distribute electricity not only in Schönau but all over Germany. EWS also started promoting the idea of local bottom-up energy transitions and the extension of its grid and its organization to neighboring communities and cities like Titisee-Neustadt (further, natural gas and electricity concessions started in the following small communities: on 1 January 2011, Fröhnd, Schönenberg, Tunau, and Wembach. 1 January 2012. On 1 January 2013 followed Wieden, Aitern, Utzenfeld, as well as Schönau-Aiterfeld as part of the city of Schönau [53]). Citizens from neighbor communities were given a say in the city council and participated in the capitalization of the operated electricity grid which they, like EWS, bought from the former operating utility.

- Solarcomplex. In 2005, Solarcomplex planned its first bioenergy village. The bioenergy village-series marks a new generation of projects (List of Solarcomplex’ Bioenergy villages: Mauenheim 2006, Lippertsreute 2008, Grosselfingen 2008, Schlatt 2009, Randegg 2009, Renquishausen 2009, Lautenbach 2010, Weiterdingen 2011, Meßkirch 2011, Büsingen 2012, Emmingen 2013, Bonndorf 2014/2015, Hilzingen 2015, Bonndorf 2015, Wald 2015/2016, Veringendorf 2016/2017, Storzingen 2017 [59]. This concerns also the collaboration with small neighboring towns like Engen, where passive energy house settlements relying on photovoltaics and wood pellet heating were built [60].) and makes particular use of photovoltaics and bioenergy heating systems, as professionalized during the establishment phase, but also a biogas plant and waste heat utilization (2018). In August 2012, an industry representative group, IG Hegauwind, was founded to escape discursive deadlocks in the regional wind sector. Since existing regional wind zoning rules were not sufficient, their own wind measurements started in 2013 [61] (Founding members IG Hegauwind were the Bürger-Energie Bodensee e.G., EKS AG, Gemeindewerke Steißlingen, Solarcomplex, Städtische Werke Schaffhausen/Neuhausen, Stadtwerke Engen, Stadtwerke Konstanz, Stadtwerke Radolfzell, Stadtwerke Singen, Stadtwerke Stockach, Stadtwerke Tuttlingen and the Thüga Energie [61]).

- BINSE. In 2004, BINSE participated for the first time in the national solar and photovoltaic competition (German: Solarbundesliga), which aims to honor innovative communities. This platform helped BINSE to share experiences, and refine its future vision [38] (Between 2002 and 2006, BINSE realized 50 photovoltaic and solar heat projects [62]. Later in 2009, BINSE realized a 10 kWp photovoltaic project in the neighboring district of Halden-Hagen on the rooftop of the Protestant-Lutheran Peace Church Halden-Hagen [63]. In 2010, a solar recharging station for e-mobility was installed. Furthermore, since 2012, BINSE has installed 20 wood-pellet-based heating systems and organized a platform to gather pellets). For instance, in 2012, a pioneering facility wood-pellet-based heating system was constructed in the parish house of the local Berchum Protestant church [64], which obviously became BINSE’s experimental incubation room (interviews 5, 34). Soon BINSE started other projects that did not rely on cooperation with local churches.

4.2.2. Non-Place-Bound Narrative Factors

4.2.3. Place-Bound Narrative Factors

4.2.4. Adopters and Bottom-Up Energy Transition Narratives

4.2.5. Intermediate Results

5. Discussion

5.1. Points of Contention on Landscape Level during the Establishment Phase

5.2. Readjusting the Catastrophe during the Adoption Phase

5.3. Establishing Place-Bound Stories of Civil Society’s Success

5.4. Adopting Local Success Stories and the Fixity–Travel Dilemma

6. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Interviews in Chronological Order

- Face to face, 3 interviewees, 24.02.2011, Schönau.

- Face to face, 15.04.2011, Singen.

- Face to face, 2 interviewees, 18.05.2011, Hagen, Berchum.

- Face to face, 11.07.2011, Singen.

- Face to face, 2 interviewees, 11.7.2011, Singen.

- Face to face, 12.07.2011, Singen.

- Face to face, 12.07.2011, Singen.

- Face to face, 13.07.2011, Singen.

- Face to face, 13.07.2011, Schönau.

- Face to face, 13.07.2011, Schönau.

- Face to face, 13.07.2011, Singen.

- Face to face, 13.07.2011, Singen.

- Face to face, 14.07.2011, Schönau.

- Face to face, 14.07.2011, Schönau.

- Face to face, 14.7.2011, Schönau.

- Face to face, 15.07.2011, Schönau.

- Face to face, 15.07.2011, Schönau.

- Face to face, 22.07.2011, Iserlohn.

- Face to face, 22.7.2011, Hagen.

- Face to face, 3 interviewees, 15.08.2012, Essen.

- Telephone, 04.09.2012, Schönau.

- Face to face, 05.09.2012, Stuttgart.

- Telephone, 10.10.2012, Waldshut-Tiengen.

- Telephone, 22.10.2012,Schönau

- Face to face, 25.10.2012, Köln.

- Face to face, 30.10.2012, Essen.

- Telephone, 05.11.2012, Schönau.

- Telephone, 07.11.2012, Singen.

- Face to face, 07.11.2012, Singen.

- Telephone, 13.11.2012, Singen.

- Telephone, 13.11.2012, Konstanz.

- Face to face, 28.11.2012, Essen.

- Face to face, 30.11.2012, Hagen, Berchum.

- Telephone, 07.12.2012, Hagen, Berchum.

- Face to face, 08.12.2012, Hagen, Berchum.

- Face to face, 2 interviewees, 10.12.2012, Singen.

- Face to face, 11.12.2012, Singen.

- Face to face, 08.02.2013, Schönau.

- Face to face, 08.02.2013, Schönau.

- Face to face, 09.02.2013, Schönau.

- Face to face, 3 interviewees, 09.02.2013, Schönau.

- Telephone, 20.02.2013, Schönau.

- Telephone, 01.03.2013, Schönau.

- Face to face, 13.08.2013, Iserlohn.

- Telephone, 06.08.2014, Hagen, Berchum.

References

- Espinosa, C.; Pregernig, M. Narrative und Diskurse in der Umweltpolitik: Möglichkeiten und Grenzen Ihrer Strategischen Nutzung; Federal Environment Agency: Dessau-Roßlau, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, T.J. Reading Policy Narratives: Beginnings, Middles, and Ends. In The Argumentative Turn in Policy Analysis and Planning, 2nd ed.; Fischer, F., Forester, J., Eds.; UCL Press, Taylor and Francis: London, UK, 2002; pp. 167–185. [Google Scholar]

- Viehöver, W. Diskurse als Narrationen. In Handbuch Sozialwissenschaftliche Diskursanalyse; Keller, R., Hirseland, A., Schneider, W., Viehöver, W., Eds.; VS-Verlag: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2006; pp. 179–208. [Google Scholar]

- Gadinger, F.; Jarzebski, S.; Yildiz, T. Politische Narrative. Konturen einer politikwissenschaftlichen Erzähltheorie. In Politische Narrative. Konzepte—Analysen—Forschungspraxis; Gadinger, F., Jarzebski, F., Yildiz, T., Eds.; Springer: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2014; pp. 3–38. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, L.; Müller, A.P. Narrative and Innovation. In Narrative and Innovation: New Ideas for Business Administration, Strategic Management and Entrepreneurship; Müller, A.P., Becker, L., Eds.; Springer: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2013; pp. 11–29. [Google Scholar]

- Tooth, R.; Renshaw, P. Reflections on pedagogy and place: A journey into learning for sustainability through environmental narrative and deep attentive reflection. Aust. J. Environ. Educ. 2009, 25, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A. Green niches in sustainable development: The case of organic food in the United Kingdom. Environ. Plan. C Gov. Policy 2006, 24, 439–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A. Translating Sustainabailities between Green Niches and Socio-Technical Regimes. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2007, 19, 427–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermwille, L. The role of narratives in socio-technical transitions—Fukushima and the energy regimes of Japan, Germany, and the United Kingdom. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2016, 11, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.; Raven, R. What is protective space? Reconsidering niches in transitions to sustainability. Res. Policy 2012, 41, 1025–1036. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, G.; Kraftl, P.; Pickerill, J.; Upton, C. Holding the future together: Towards atheorisation of the spaces and times of transition. Environ. Plan. A 2012, 44, 1607–1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feola, G.; Nunes, R. Success and failure of grassroots innovations for addressing climate change: The case of the Transition Movement. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2014, 24, 232–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geels, F.W. The multi-level perspective on sustainability transitions: Responses to seven criticisms. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2011, 1, 24–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geels, F.W. Technological transitions as evolutionary reconfiguration processes: A multi-level perspective and a case study. Res. Policy 2002, 31, 1257–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geels, F.; Schot, J. Typology of sociotechnical transition pathways. Res. Policy 2007, 36, 399–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franceschini, S.; Pansera, M. Beyond unsustainable eco-innovation: The role of narratives in the evolution of the lighting sector. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2015, 92, 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feola, G.; Butt, A. The diffusion of grassroots innovations for sustainability in Italy and Great Britain: An exploratory spatial data analysis. Geogr. J. 2017, 183, 16–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buijs, A.E.; Mattijssen, T.J.; Van der Jagt, A.P.; Ambrose-Oji, B.; Andersson, E.; Elands, B.H.; Møller, M.S. Active citizenship for urban green infrastructure: Fostering the diversity and dynamics of citizen contributions through mosaic governance. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2016, 22, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frantzeskaki, N.; Dumitru, A.; Anguelovski, I.; Avelino, F.; Bach, M.; Best, B.; Binder, C.; Barnes, J.; Carrus, G.; Egermann, M.; et al. Elucidating the changing roles of civil society in urban sustainability transitions. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2016, 22, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thörn, H.; Svenberg, S. ‘We feel the responsibility that you shirk’: Movement institutionalization, the politics of responsibility and the case of the Swedish environmental movement. Soc. Mov. Stud. 2016, 15, 593–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittmayer, J.M.; Avelino, F.; van Steenbergen, F.; Loorbach, D. Actor roles in transition: Insights from sociological perspectives. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2017, 24, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, E. Diffusion of Innovation; Free Press: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Dryzek, J. The Politics of the Earth: Environmental Discourses, 2nd ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Keller, R. Doing Discourse Research: An Introduction for Social Scientists; Sage: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Espinosa, C. Interpretive Affinities: The Constitutionalization of Rights of Nature, Pacha Mama, in Ecuador. J. Environ. Policy Plan. 2015, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, D.A. Causal Stories and the Formation of Policy Agendas. Political Sci. Q. 1989, 104, 281–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajer, M. The Politics of Environmental Discourse: Ecological Modernization and the Policy Process; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, J.D.; Chang, H.C. Internal and External Communication, Boundary Spanning, and Innovation Adoption: An Over-Time Comparison of Three Explanations of Internal and External Innovation Communication in a New Organizational Form. J. Bus. Commun. 2000, 37, 238–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barca, S. Energy, property, and the industrial revolution narrative. Ecol. Econ. 2011, 70, 1309–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, M. Exnovation as a successful strategy for energy transitions. In Oxford Energy and Society Handbook; Davidson, D., Gross, M., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018; pp. 520–537, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Gerhards, J. Framing dimensions and framing strategies: Contrasting ideal- and real-type frames. Soc. Sci. Inf. 1995, 34, 225–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa, C. The riddle of leaving the oil in the soil—Ecuador’s Yasuní-ITT project from a discourse perspective. For. Policy Econ. 2013, 36, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnam-Fink, M. Creating narrative scenarios: Science fiction prototyping at Emerge. Futures 2015, 70, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welzer, H. Selbst Denken: Eine Anleitung zum Widerstand; Fischer Verlag: Frankfurt am Main, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lakoff, G. Why it Matters How We Frame the Environment. Environ. Commun. 2010, 4, 70–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dedaic, M.N. Political speeches and persuasive argumentation. In Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics, 2nd ed.; Brown, K., Ed.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2005; pp. 700–705. [Google Scholar]

- Koselleck, R. Vergangene Zukunft: Zur Semantik Geschichtlicher Zeiten; Suhrkamp: Berlin, Germany, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- David, M.; Schönborn, S. Die Energiewende als Bottom-up-Innovation—Wie Pionierprojekte das Energiesystem Verändern; Reihe Transformationen, Oekom: Munich, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Storey, C.D.; Perks, H. Mixing rich and asynchronous communication for new service development performance. R&D Manag. 2014, 45, 107–125. [Google Scholar]

- Jørgensen, M.; Phillips, L. Discourse Analysis as Theory and Method; SAGE: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Cronon, W. A place for stories: Nature, history, and narrative. J. Am. Hist. 1992, 78, 1347–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettigrew, A.M. Longitudinal field research on change: Theory and Practice. Organ. Sci. 1990, 1, 267–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellman, J. Telling space and making stories: Art, narrative, and place. Art Educ. 1998, 51, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grunebaum-Ralph, H. Re-placing pasts, forgetting presents: Narrative, place, and memory in the time of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. Res. Afr. Lit. 2001, 32, 198–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaser, B.G. Retreading Research Materials: The Use of Secondary Analysis by the Independent Researcher. Am. Behav. Sci. 1963, 6, 11–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medjedovic, I.; Witzel, A. Sekundäranalyse Qualitativer Interviews. Verwendung von Kodierungen der Primärstudie am Beispiel einer Untersuchung des Arbeitsprozesswissens junger Facharbeiter Forum für qualitative Sozialforschung. 2005. Available online: https://www.ssoar.info/ssoar/handle/document/9224 (accessed on 30 January 2018).

- Abbott, A. Time Matters, On Theory and Method; The University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Lange, M. Comparative Historical Methods; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Poole, M.S.; Van de Ven, A.H.; Dooley, K.; Holmes, M.E. Organizational Change and Innovation Processes, Theory and Methods for Research; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Eltern für Atomfreie Zukunft e.V. Available online: http://www.efaz-schoenau.de/index.html (accessed on 28 January 2018).

- Müller, B. solarcomplex—Regionale Wertschöpfung in Millionenhöhe durch erneuerbare Energien. Umweltwirtschaftsforum 2007, 15, 162–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renn, O.; Marshall, J.P. Coal, nuclear and renewable energy policies in Germany: From the 1950s to the “Energiewende”. Energy Policy 2016, 1, 224–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graichen, P. Eine Public-Choice-Analyse der »Stromrebellen« von Schönau; Campus: Frankfurt am Main, Germany, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Nolte, W. Energie—Klimafreundlich und in Bürgerhand. Oya Anders Denken Anders Leben 2010, 4, 43–45. [Google Scholar]

- Oberer, F. Unternehmen Solarcomplex. Energ. Pflanz. 2010, 6, 24–26. [Google Scholar]

- Grassl, H.; Hennicke, P.; Kreibich, R. Erneuerbare Energien in der Region Hegau/Bodensee, Übersicht der Technisch Verfügbaren Potentiale; Wissenschaftlicher Beirat von Solarcomplex GmbH: Singen, Germany, 2002; Available online: http://www.bbsw.de/websitebaker-2.6.4-test/wb/media/Service/Download/potentialstudie_gross.pdf (accessed on 26 January 2018).

- Schönborn, S.; Gellrich, A.; David, M. Kirchengemeinden im Diffusionsprozess—Schlüssel zu neuen Milieus? Der qualitative und quantitative Blick auf Kirchengemeinden im Verbreitungsprozess Erneuerbarer Energien. GAIA 2014, 23, 236–242. [Google Scholar]

- David, M. Bürger-Energiewende: Wissen Durch Handeln? Eine Komparative Fallstudie über Soziale Dynamiken der Wissensgenese Zweier Deutscher Unternehmen im Erneuerbaren Energiebereich; Reihe Umweltsoziologie, Nomos: Baden-Baden, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Solarcomplex. Sonne, Wind, Wärme. 2018. Available online: http://www.solarcomplex.de/ (accessed on 30 January 2018).

- Solar System Haus, Bauen. 2018. Available online: http://www.solarsystemhaus.de (accessed on 26 January 2018).

- Solarcomplex. Wir Machen Ihre Windmessung, Die Kombilösung: Langzeitdaten + LiDAR. 2014. Available online: http://www.solarcomplex.de/info/service/windmessung.php (accessed on 7 January 2018).

- Hug, R. Solar-Politik von unten: Deutsche Solarinitiativen wollen die Energiewende. Solar-Report. 16 January 2007. Available online: http://www.solarserver.de/solarmagazin/artikeljanuar2007.html (accessed on 30 January 2018).

- Müller, B. Bioenergiedörfer—Bausteine der Energiewende im ländlichen Raum. Solarzeitalter 2013, 25, 83–85. [Google Scholar]

- Berchumer Initiative für Solare Energien e.V. [BINSE] Aus der Arbeit der Solarinitiative BINSE, 2011, internal document. Available online: http://binse.org/ (accessed on 30 January 2018).

- DerWesten.de, 17. Tour de Ruhr führt Sonntag ins Solardorf. 25 June 2008. Available online: http://www.derwesten.de/staedte/hohenlimburg/17-tour-de-ruhr-fuehrt-sonntag-ins-solardorf-id940425.html (accessed on 3 January 2018).

- Janzing, B. Störfall mit Charme, die Schönauer Stromrebellen im Widerstand Gegen Atomkraft; Dold Verlag: Vöhrenbach, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Stellmach, P. Hunderttausende Euro Schadensersatz für Titisee-Neustadt. Badische Zeitung. 2017. Available online: http://www.badische-zeitung.de/titisee-neustadt/hunderttausende-euro-schadensersatz-fuer-titisee-neustadt--144050374.html (accessed on 20 January 2018).

- Trah, C. Wind aus Südwest. Südkurier, 5 June 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Pedriana, N. Rational choice, structural context, and increasing returns: A strategy for analytic narrative in historical sociology. Sociol. Methods Res. 2005, 33, 349–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D.; Lewis, A. Organizing for Energy Democracy in Rural Electric Cooperatives. In Energy Democracy—Advancing Equity in Clean Energy Solutions; Fairchild, D., Weinrub, A., Eds.; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2017; pp. 93–112. [Google Scholar]

- Szulecki, K. Conceptualizing energy democracy. Environ. Politics 2018, 27, 21–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunze, C.; Becker, S. Collective ownership in renewable energy and opportunities for sustainable degrowth. Sustain. Sci. 2015, 10, 25–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felt, U.; Wynne, B. Taking European Knowledge Society Seriously; Office for Official Publications of the European Communities: Brussels, Belgium, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Tishman, M. Community-Anchor Strategies for Energy Democracy. In Energy Democracy—Advancing Equity in Clean Energy Solutions; Fairchild, D., Weinrub, A., Eds.; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2017; pp. 173–194. [Google Scholar]

| ←Cross-Case Comparison→ | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ←Within-case comparison→ | ←Within-case→ comparison | 4.1.1 Case briefings: establishment phase | EWS | Solarcomplex | BINSE | Establishment phase |

| 4.1.2 Non-place-bound narrative factors | ||||||

| 4.1.3 Place-bound narrative factors | ||||||

| 4.1.4 Intermediate results | ||||||

| ←Within-case→ comparison | 4.2.1 Case briefings: adoption phase | EWS | Solarcomplex | BINSE | Adoption phase | |

| 4.2.2 Non-place-bound narrative factors | ||||||

| 4.2.3 Place-bound narrative factors | ||||||

| 4.2.4 Adopters and bottom-up energy transition narratives | ||||||

| 4.2.5 Intermediate results | ||||||

| 5. Discussion (non-place-bound and place-bound narrative factors) | ||||||

| 6. Conclusions | ||||||

| Bottom-Up Transition Narrative Factors on Different Levels | EWS | Solarcomplex | BINSE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-place-bound | Sociotechnical landscape level | Chernobyl effects | Possible climate change | Integrity of creation |

| Sociotechnical regime level | Utility contract | Feed-in tariff | Feed-in tariff | |

| Place-bound | Sociotechnical niche level | Civil society - Church groups - Colleagues - Experts | Civil society - Friends from school - Colleagues - Business networks - Experts | Civil society - Church groups - Experts |

| Bottom-Up Transition Narrative Factors on Different Levels | EWS | Solarcomplex | BINSE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-place-bound | Sociotechnical landscape level | Argument - Fukushima - Possible climate change | Argument - Fukushima - Possible climate change | Argument - Fukushima - Possible climate change - Integrity of creation |

| Sociotechnical regime level | Argument - Liberalization of the electricity market - Adopters | Argument - Liberalization of the electricity market - Adopters | Argument - Liberalization of the electricity market - Adopters | |

| Barrier - Unloyalty to own narrative - Local affairs | Barrier - Ecosystem boundaries - Sociotechn. boundaries - Local affairs | Barrier - Bureaucracy | ||

| Place-bound | Sociotechnical niche level | Argument - Businesses - Friends - Neighbor communities - Adopters - Politicians - Experts | Argument - Businesses - Friends - Neighbor communities - Adopters - Politicians - Experts | Argument - Adopters - Church groups - Experts |

| Barrier - Liberalization of the electricity market - Professionalization - Local affairs | Barrier - Ecosystem boundaries (wood) - Sociotechn. Boundaries (rooftops) - Local affairs | |||

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

David, M.; Schönborn, S. Bottom-Up Energy Transition Narratives: Linking the Global with the Local? A Comparison of Three German Renewable Co-Ops. Sustainability 2018, 10, 924. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10040924

David M, Schönborn S. Bottom-Up Energy Transition Narratives: Linking the Global with the Local? A Comparison of Three German Renewable Co-Ops. Sustainability. 2018; 10(4):924. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10040924

Chicago/Turabian StyleDavid, Martin, and Sophia Schönborn. 2018. "Bottom-Up Energy Transition Narratives: Linking the Global with the Local? A Comparison of Three German Renewable Co-Ops" Sustainability 10, no. 4: 924. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10040924

APA StyleDavid, M., & Schönborn, S. (2018). Bottom-Up Energy Transition Narratives: Linking the Global with the Local? A Comparison of Three German Renewable Co-Ops. Sustainability, 10(4), 924. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10040924