The Relationship between Social Visibility and CSR Disclosure

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. CSR Disclosure about Developing Countries

3. Theoretical Framework

CSR Disclosure

Social Visibility

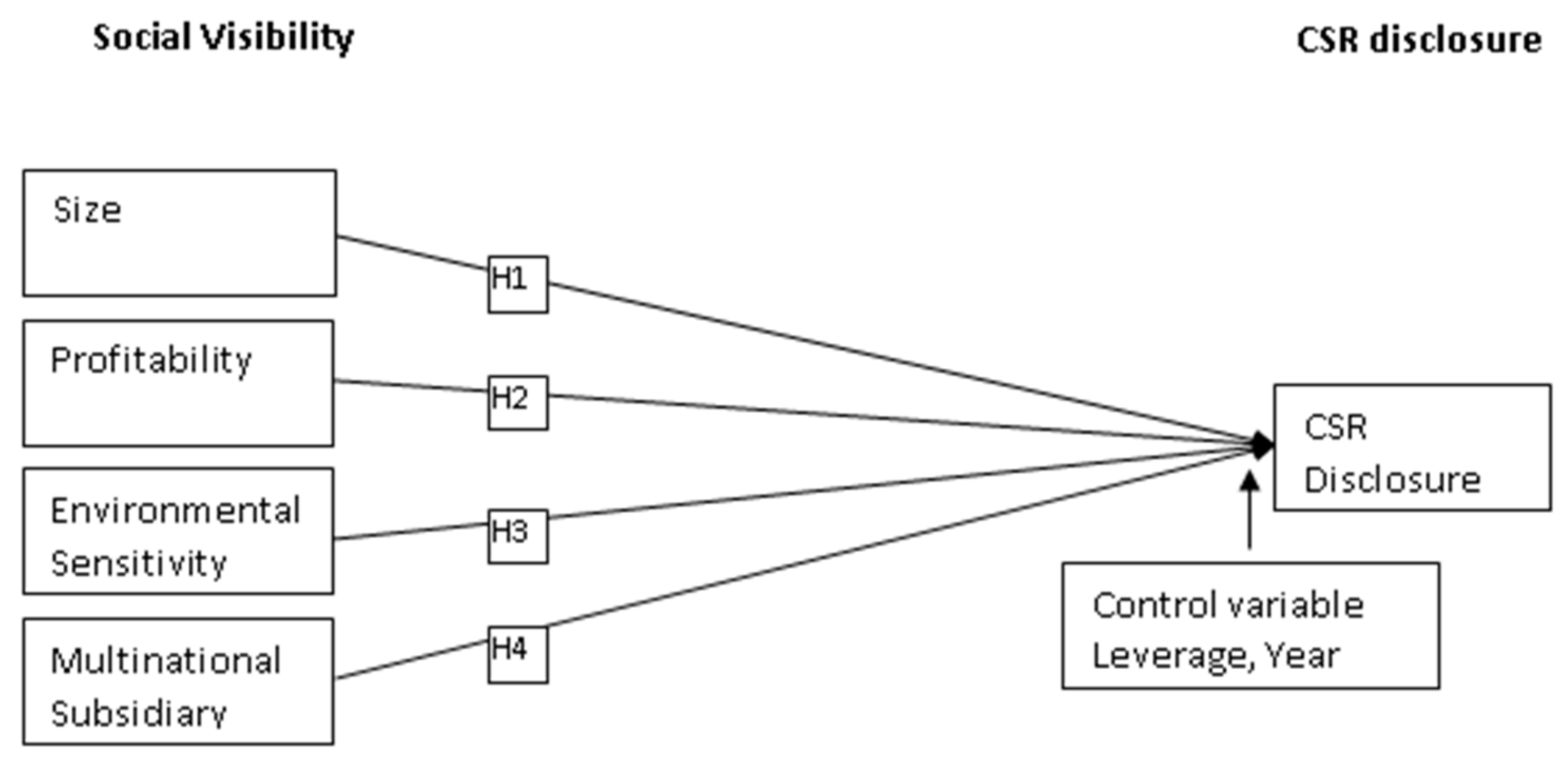

Hypotheses

Company’s Size

Company’s Profitability

Industry’s Sensitivity

Multinational Companies Subsidiaries

Control Variable

4. Materials and Methods

Research Method

Sample

Measurement of Dependent and Independent Variables

CSR Disclosure

Data Analysis Technique

- CS: Company Size

- CP: Corporate Profitability

- ES: Environmental sensitivity

- MNNs: Multinationals Subsidiaries

- t = 2008 and 2011

- i = 1, 2, 3… 253.

5. Results

Descriptive Results

Regression Analysis Assumptions

Regression Analysis Results

Robustness of Results

6. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Company’s Name: | Company’s Sector: | ||

| Company’s Products: | |||

| Company’s Code: | Total Score: | ||

| Coder’s Name: | □ □ |

| Disclosure Themes and Indicators | Where to locate information | Identification of indicator | Score |

| A. ENVIRONMENTAL DISCLOSURE: 1. Environmental Pollution: AIMS/INTENTIONS:

| Vi/Mii/CViii/SEiv |

| |

ACTIONS:

| DRvi/CSRSvii/ES viii |

| |

PERFORMANCE:

| DR/CSRS/ES |

| |

| 2. Conservation of Natural Resourcesix: AIMS/INTENTIONS:

| V/M/CV/SE |

| |

ACTIONS:

| CSRS/ES |

| |

PERFORMANCE:

| DR/C SRS/ES |

| |

| 3. Energy: AIMS/INTENTIONS:

| V/M/CV/SE |

| |

ACTIONS:

| DR/CSRS/ES |

| |

PERFORMANCE:

| DR/CSRS/ES |

| |

| 4. Aesthetics: AIMS/INTENTIONS:

| V/M/CV/SE |

| |

ACTIONS:

| DR/CSRS/ES |

| |

PERFORMANCE:

| DR/CSRS/ES |

| |

| 5. Environment Other: AIMS/INTENTIONS:

| V/M/CV/SE/CSRS |

| |

ACTIONS:

| DR/CSRS/ES |

| |

PERFORMANCE:

| DR/CSRS/ES |

| |

| B. HUMAN RESOURCE DISCLOSURE: 1. Training and Staff Development: AIMS/INTENTIONS:

| V/M/CV/SE |

| |

ACTIONS:

| DR/CSRS/EmpSx |

| |

PERFORMANCE:

| DR/EmpS/CNxi |

| |

| 2. Pay and Benefits:xii AIMS/INTENTIONS:

| V/M/CV/SE |

| |

ACTIONS:

| DR/EmpS POSxiii NTFSxiv |

| |

PERFORMANCE:

| DR/CSRS/EmpS/CN NTFS |

| |

| 3. Participation and Staff Involvement: AIMS/INTENTIONS:

| V/M/CV/SE |

| |

ACTIONS:

| DR/CSRS/EmpS/CN |

| |

PERFORMANCE:

| DR/CSRS/EmpS |

| |

| 4. Health and Safety and Individual Well-being: AIMS/INTENTIONS:

| V/M/CV/SE |

| |

ACTIONS:

| DR/CSRS/EmpS |

| |

PERFORMANCE:

| DR/CSRS/EmpS/CN |

| |

| 5. Measurement of Policies: AIMS/INTENTIONS:

| V/M/CV/SE |

| |

PERFORMANCE:

| DR/CSRS/EmpS |

| |

| 6. Employment Policy: AIMS/INTENTIONS:

| V/M/CV/SE |

| |

ACTIONS:

| DR/CSRS/EmpS |

| |

PERFORMANCE:

| DR/CSRS/EmpS |

| |

| 7. Equal Opportunities: AIMS/INTENTIONS:

| V/M/CV/SE |

| |

ACTIONS:

| DR/CSRS/EmpS |

| |

PERFORMANCE:

| DR/CSRS/EmpS |

| |

| 8. Work–life Balance: AIMS/INTENTIONS:

| V/M/CV/SE/CSRS |

| |

ACTIONS:

| DR/CSRS/EmpS |

| |

PERFORMANCE:

| DR/CSRS/EmpS |

| |

| C. PRODUCTS AND CONSUMERS DISCLOSURE: 1. Product Developments: AIMS/INTENTIONS:

| CSRS |

| |

ACTIONS:

| DR/CSR/PSxvii |

| |

PERFORMANCE:

| DR/CSRS/PS |

| |

| 2. Product Safety: AIMS/INTENTIONS:

| V/M/CV/SE/CSRS |

| |

ACTIONS:

| DR/CSRS/PS |

| |

PERFORMANCE:

| DR/CSRS/PS |

| |

| 3. Product Quality: AIMS/INTENTIONS:

| V/M/CV/SE/CSRS |

| |

ACTIONS:

| DR/CSRS/PS/Awards section |

| |

PERFORMANCE:

| DR/CSRS/PS/Awards section |

| |

| 4. Consumers’ Relations**: AIMS/INTENTIONS:

| V/M/CV/SE/CSRS |

| |

ACTIONS:

| DR/CSRS/PS |

| |

PERFORMANCE:

| DR/CSRS/PS |

| |

| D. COMMUNITY INVOLVEMENT DISCLOSURE: 1. Support for Education/training ***: AIMS/INTENTIONS:

| V/M/CV/SE/CSRS |

| |

ACTIONS:

| DR/CSRS/CRxviii |

| |

PERFORMANCE:

| DR/CSRS/CR |

| |

| 2. Support for Art and Culture: AIMS/INTENTIONS:

| V/M/CV/SE/CSRS |

| |

ACTIONS:

| DR/CSRS/CR |

| |

PERFORMANCE:

| DR/CSRS/CR |

| |

| 3. Support for Public Health ***: AIMS/INTENTIONS:

| V/M/CV/SE/CSRS |

| |

ACTIONS:

| DR/CSRS/CR |

| |

PERFORMANCE:

| DR/CSRS/CR |

| |

| 4. Sponsoring Sporting or Recreational Projects ***: AIMS/INTENTIONS:

| V/M/CV/SE/CSRS |

| |

ACTIONS:

| DR/CSRS/CR |

| |

PERFORMANCE:

| DR/CSRS/CR |

| |

| 5. Other Community Activities ***: AIMS/INTENTIONS:

| V/M/CV/SE/CSRS |

| |

ACTIONS:

| DR/CSRS/CR |

| |

PERFORMANCE:

| DR/CSRS/CR NTFSxix |

| |

| E. GENERAL DISCLOSURE: Includes disclosure which will not be covered by above CSR disclosure categories: environment, human resource, products and consumers, and community involvement disclosure. For example: Vendors/partners training and education.

|

| ||

ACTIONS:

|

| ||

PERFORMANCE:

|

| ||

| SOCIAL VISIBILITY VARIABLES: | |||

| Total Assets (0,000): ………………………………………… Total Debts (0,000):…………………………………………. Net Income (Net profit after taxes) (0,000): ……………………………………… Industry Sensitivity (If a company is operating in industry having SIC code 28XX excluding 283X, 22XX, 26XX, and 2911) Whether the company is a subsidiary of Multinationals □ Yes No □ |

References

- Branco, M.C.; Rodrigues, L.L. Factors influencing social responsibility disclosure by Portuguese companies. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 83, 685–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahadeo, J.; Oogarah–Hanuman, V.; Soobaroyen, T. A longitudinal study of corporate social disclosures in a developing economy. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 104, 545–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reverte, C. Determinants of corporate social responsibility disclosure ratings by Spanish listed firms. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 88, 351–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laan Smith, J.; Adhikari, A.; Tondkar, R.H. Exploring differences in social disclosures internationally: A stakeholder perspective. J. Account. Public Policy 2005, 24, 123–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amran, A.; Devi, S.S. The impact of government and foreign affiliate influence on corporate social reporting: The case of Malaysia. Manag. Audit. J. 2008, 23, 386–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagesson, T.; Blank, V.; Broberg, P.; Collin, S. What explains the extent and content of social and environmental disclosures on corporate websites: A study of social and environmental reporting in Swedish listed corporations? Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2009, 16, 352–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Kung, F. Drivers of environmental disclosure and stakeholder expectation: Evidence from Taiwan. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 96, 435–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, W.; Chang, Y.; Martynov, A. The effect of ownership structure on corporate social responsibility: Empirical evidence from Korea. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 104, 283–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, T.; Wang, Y. Determinants of social disclosure quality in Taiwan: An application of stakeholder theory. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 121, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorne, L.; Mahoney, L.S.; Manetti, G. Motivations for issuing standalone CSR reports: A survey of Canadian firms. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2014, 27, 686–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patten, D.M. Exposure, legitimacy, and social disclosure. J. Account. Public Policy 1991, 10, 297–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deegan, C. Introduction: The legitimising effect of social and environmental disclosures—A theoretical foundation. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2002, 15, 282–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deegan, C.; Rankin, M.; Tobin, J. An examination of the corporate social and environmental disclosures of BHP from 1983–1997: A test of legitimacy theory. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2002, 15, 312–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, L.D. Social and environmental accountability research: A view from the commentary box. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2005, 18, 842–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Dwyer, B. Managerial perceptions of corporate social disclosure: An Irish story. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2002, 15, 406–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, D. Chronicles of wasted time? A personal reflection on the current state of, and future prospects for, social and environmental accounting research. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2008, 21, 240–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blowfield, M.; Murray, A. Corporate Responsibility, 2nd ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, W.; Frynas, J.G.; Mahmood, Z. Determinants of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Disclosure in Developed and Developing Countries: A Literature Review. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2017, 24, 261–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belal, A.R.; Owen, D.L. The views of corporate managers on the current state of, and future prospects for, social reporting in Bangladesh: An engagement–based study. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2007, 20, 472–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, W.; Frynas, J.G. The Role of Normative CSR-Promoting Institutions in Stimulating CSR Disclosures in Developing Countries. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belal, A.R. A study of corporate social disclosures in Bangladesh. Manag. Audit. J. 2001, 16, 274–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.A.; Deegan, C. Motivations for an organisation within a developing country to report social responsibility information. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2008, 21, 850–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, R.; Kouhy, R.; Lavers, S. Corporate social and environmental reporting: A review of the literature and a longitudinal study of UK disclosure. Account. Audit. Account. J. 1995, 8, 47–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fifka, M.S. Corporate Responsibility Reporting and its Determinants in Comparative Perspective—A Review of the Empirical Literature and a Meta-analysis. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2013, 22, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Villiers, C.; van Staden, C.J. Can less environmental disclosure have a legitimising effect? Evidence from Africa. Account. Organ. Soc. 2006, 31, 763–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohd Ghazali, N.A. Ownership structure and corporate social responsibility disclosure: Some Malaysian evidence. Corp. Gov. 2007, 7, 251–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kansal, M.; Joshi, M.; Batra, G.S. Determinants of corporate social responsibility disclosures: Evidence from India. Adv. Account. 2014, 30, 217–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haji, A.A. Corporate social responsibility disclosures over time: Evidence from Malaysia. Manag. Audit. J. 2013, 28, 647–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belal, A.R.; Momin, M. Corporate social reporting (CSR) in emerging economies: A review and future direction. Res. Account. Emerg. Econ. 2009, 9, 119–143. [Google Scholar]

- Haniffa, R.M.; Cooke, T.E. The impact of culture and governance on corporate social reporting. J. Account. Public Policy 2005, 24, 391–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holder-Webb, L.; Cohen, J.R.; Nath, L.; Wood, D. The supply of corporate social responsibility disclosures among U.S. firms. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 84, 497–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, W. Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosure (CSRD): A Case Study of Pakistan. Ph.D. Thesis, Middlesex University, London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Abu, B.A.; Ameer, R. Readability of corporate social responsibility communication in Malaysia. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2011, 18, 50–60. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, D.R.; Ahuja, J.M. Corporate social reporting in India. Int. J. Account. 1983, 18, 151–169. [Google Scholar]

- Gul, S.; Muhammad, F.; Rashid, A. Corporate Governance and Corporate Social Responsibility: The Case of Small, Medium, and Large Firms. Pak. J. Commer. Soc. Sci. 2017, 11, 01–34. [Google Scholar]

- Wanderley, L.; Lucian, R.; Farache, F.; Sousa Filho, J. CSR information disclosure on the web: A context–based approach analysing the influence of country of origin and industry sector. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 82, 369–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, S.M. Voluntary environmental and social accounting disclosure practices in the Asia–Pacific region: An international empirical test of political economy theory. Int. J. Account. 1999, 34, 209–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamla, R. Critically Appreciating Social Accounting and Reporting in the Arab Middle East: A Postcolonial Perspective. Adv. Int. Account. 2007, 20, 105–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teoh, H.Y.; Thong, G. Another look at corporate social responsibility and reporting: An empirical study in a developing country. Account. Organ. Soc. 1984, 9, 189–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Muttakin, M.B.; Siddiqui, J. Corporate governance and corporate social responsibility disclosures: Evidence from an emerging economy. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 114, 207–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahaman, A.S.; Lawrence, S.; Roper, J. Social and environmental reporting at the VRA: Institutionalised legitimacy or legitimation crisis? Crit. Perspect. Account. 2004, 15, 35–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsang, E.W. A longitudinal study of corporate social reporting in Singapore: The case of the banking, food and beverages and hotel industries. Account. Audit. Account. J. 1998, 11, 624–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amran, A.; Devi, S.S. Corporate social reporting in Malaysia: A political theory perspective. Malays. Account. Rev. 2007, 6, 19–44. [Google Scholar]

- Momin, M.A.; Parker, L.D. Motivations for corporate social responsibility reporting by MNC subsidiaries in an emerging country: The case of Bangladesh. Br. Account. Rev. 2013, 45, 215–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belal, A.R.; Cooper, S. The absence of corporate social responsibility reporting in Bangladesh. Crit. Perspect. Account. 2011, 22, 654–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, C.G.; Hill, T. Corporate social and environmental reporting and the impact of internal environmental policy in South Africa. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2009, 16, 48–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Villiers, C.J. Why do South African companies not report more environmental information when managers are so positive about this kind of reporting? Meditari Account. Res. 2003, 11, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuasirikun, N. Attitudes to the development and implementation of social and environmental accounting in Thailand. Crit. Perspect. Account. 2005, 16, 1035–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, W.; Sandhu, M.A.; Iqbal, J.; Tufail, M.S. Corporate Governance and CSR Disclosure: Evidence from a Developing Country. Pak. J. Soc. Sci. 2016, 36, 225–238. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, H.U.Z. The effect of corporate governance elements on corporate social responsibility (CSR) reporting: Empirical evidence from private commercial banks of Bangladesh. Int. J. Law Manag. 2010, 52, 82–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackston, D.; Milne, M.J. Some determinants of social and environmental disclosures in New Zealand companies. Account. Audit. Account. J. 1996, 9, 77–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, R.; Owen, D.; Adams, C. Accounting & Accountability: Changes and Challenges in Corporate and Environmental Reporting; Prentice Hall: Hemel Hempstead, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Deegan, C.; Gordon, B. A study of the environmental disclosure practices of Australian corporations. Account. Bus. Res. 1996, 26, 187–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guthrie, J.; Parker, L.D. Corporate social reporting: A rebuttal of legitimacy theory. Account. Bus. Res. 1989, 19, 343–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patten, D.M. Intra–industry environmental disclosures in response to the Alaskan oil spill: A note on legitimacy theory. Account. Organ. Soc. 1992, 17, 471–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, J.L. Why would corporations behave in socially responsible ways? An institutional theory of corporate social responsibility. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2007, 32, 946–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Qian, C. Corporate philanthropy and corporate financial performance: The roles of stakeholder response and political access. Acad. Manag. J. 2011, 54, 1159–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauvey, J.N.; Giordano-Spring, S.; Cho, C.H.; Patten, D.M. The normativity and legitimacy of CSR disclosure: Evidence from France. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 130, 789–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowling, J.; Pfeffer, J. Organizational legitimacy social values and organizational behaviour. Pac. Sociol. Rev. 1975, 18, 122–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindblom, C.K. The implications of organizational legitimacy for corporate social performance and disclosure. In Proceedings of the Critical Perspectives on Accounting Conference, New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- McMurtrie, T. Factors influencing the publication of social performance information: An Australian case study. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2005, 12, 129–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, C.A.; Hill, W.; Roberts, C.B. Corporate social reporting practices in Western Europe: Legitimating corporate behaviour? Br. Account. Rev. 1998, 30, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotorrío, L.; Sánchez, J. Corporate social responsibility of the most highly reputed European and North American firms. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 82, 379–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, C.A. Internal organisational factors influencing corporate social and ethical reporting: Beyond current theorising. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2002, 15, 223–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thijssens, T.; Bollen, L.; Hassink, H. Secondary stakeholder influence on CSR disclosure: An application of stakeholder salience theory. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 132, 873–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, P.; Zakaria, Z. Corporate social responsibility reporting in Malaysia. J. Corp. Citizsh. 2004, 13, 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haniffa, R.M.; Cooke, T.E. Culture, corporate governance and disclosure in Malaysian corporations. Abacus 2002, 38, 317–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulkifi, N.; Amran, A. Realising corporate social responsibility in Malaysia: A view from the accounting profession. J. Corp. Citizsh. 2006, 24, 101–114. [Google Scholar]

- Imam, S. Corporate social reporting in Bangladesh. Manag. Audit. J. 2000, 15, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habbash, M.; Habbash, M. Corporate governance and corporate social responsibility disclosure: Evidence from Saudi Arabia. Soc. Responsib. J. 2016, 12, 740–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SECP. Securities and Exchange Commission of Pakistan Annual Report 2011; Securities and Exchange Commission of Pakistan: Karachi, Pakistan, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bichta, C. Corporate socially responsible (CSR) practices in the context of Greek industry. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2003, 10, 12–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahul, H. Corporate social responsibility—An Indian perspective. Adv. Manag. 2010, 3, 42–44. [Google Scholar]

- Sangle, S. Empirical analysis of determinants of adoption of proactive environmental strategies in India. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2010, 19, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rettab, B.; Brik, A.; Mellahi, K. A study of management perceptions of the impact of corporate social responsibility on organisational performance in emerging economies: The case of Dubai. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 89, 371–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyduch, J.; Krasodomska, J. Determinants of Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosure: An Empirical Study of Polish Listed Companies. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newson, M.; Deegan, C. Global expectations and their association with corporate social disclosure practices in Australia, Singapore, and South Korea. Int. J. Account. 2002, 37, 183–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez–Batres, L.; Miller, V.V.; Pisani, M.J.; Henriques, I.; Renau-Sepulveda, J. Why do firms engage in national sustainability programs and transparent sustainability reporting? Manag. Int. Rev. 2012, 52, 107–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobhani, F.A.; Amran, A.; Zainuddin, Y. Revisiting the practices of corporate social and environmental disclosure in Bangladesh. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2009, 16, 167–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belal, A.; Owen, D.L. The rise and fall of stand–alone social reporting in a multinational subsidiary in Bangladesh: A case study. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2015, 28, 1160–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Famiola, M.; Adiwoso, S.A. Corporate social responsibility diffusion by multinational subsidiaries in Indonesia: Organisational dynamic and institutional effect. Soc. Responsib. J. 2016, 12, 117–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva Monteiro, S.M.; Aibar-Guzmán, B. Determinants of environmental disclosure in the annual reports of large companies operating in Portugal. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2010, 17, 185–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belkaoui, A.; Karpik, P.G. Determinants of the corporate decision to disclose social information. Account. Audit. Account. J. 1989, 2, 36–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, W.F.; Monsen, R.J. On the measurement of corporate social responsibility: Self–reported disclosures as a method of measuring corporate social involvement. Acad. Manag. J. 1979, 22, 501–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milne, M.J.; Adler, R.W. Exploring the reliability of social and environmental disclosures content analysis. Account. Audit. Account. J. 1999, 12, 237–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouten, L.; Everaert, P.; Van Liedekerke, L.; De Moor, L.; Christiaens, J. Corporate social responsibility reporting: A comprehensive picture? Account. Forum 2011, 35, 187–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cormier, D.; Magnan, M.; Van Velthoven, B. Environmental disclosure quality in large German companies: Economic incentives, public pressures or institutional conditions? Eur. Account. Rev. 2005, 14, 3–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, R.; Kouhy, R.; Lavers, S. Constructing a research database of social and environmental reporting by UK companies. Account. Audit. Account. J. 1995, 8, 78–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, J.; Reber, B.H. Dimensions of disclosures: Corporate social responsibility (CSR) reporting by media companies. Public Relat. Rev. 2011, 37, 166–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeghal, D.; Ahmed, S.A. Comparison of social responsibility information disclosure media used by Canadian firms. Account. Audit. Account. J. 1990, 3, 38–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CSR Order. Companies (Corporate Social Responsibility) General Order; Securities and Exchange Commission of Pakistan: Karachi, Pakistan, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Vuontisjärvi, T. Corporate social reporting in the European context and human resource disclosures: An analysis of Finnish companies. J. Bus. Ethics 2006, 69, 331–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasseldine, J.; Salama, A.I.; Toms, J.S. Quantity versus quality: The impact of environmental disclosures on the reputations of UK Plcs. Br. Account. Rev. 2005, 37, 231–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, A.A.; Md-Hashim, M.F.A.; Abu-Bakar, F. Corporate social reporting: A preliminary study of Bank Islam Malaysia Berhad (BIMB). Issues Soc. Environ. Account. 2010, 4, 18–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cormier, D.; Magnan, M. Corporate environmental disclosure strategies: Determinants, costs and benefits. J. Account. Audit. Financ. 1999, 14, 429–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patten, D.M. The relation between environmental performance and environmental disclosure: A research note. Account. Organ. Soc. 2002, 27, 763–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Li, T.; Minor, D. A Test of Agency Theory: CEO Power, Firm Value, and Corporate Social Responsibility. Int. J. Manag. Financ. 2016, 12, 611–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coles, J.L.; Daniel, N.D.; Naveen, L. Managerial incentives and risk–taking. J. Financ. Econ. 2006, 79, 431–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Social Visibility Variables | |

| Variables | Measurement (References) |

| Company Size | Total assets [30,67,87,95] |

| Corporate Profitability | Return on assets [1,3,5,11,83] |

| Industry sensitivity: | 1—A company operating in an industry having SIC code 06XX, 12XX, 10XX, 13XX, 19XX, 17XX, 20XX,21XX, 22XX, 23XX, 24XX, 29XX, 27XX, 35Xx, 41XX, 51XX, 49XX, and 50XX 0—Otherwise [1,82,96] |

| Multinational Subsidiaries | 1 is assigned to company which is a subsidiary of a multinational and 0 if otherwise [82] |

| Control Variables | |

| Leverage | Total debts divided by total assets [1,67,83] |

| Variables | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | Std. Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSR disclosure (extent)-CSRD | 00 | 672 | 45.03 | 73.90 |

| Profitability (ROA) | −45.25% | 44.25% | 3.30% | 10.27% |

| Company Size (0.000)-CS | 11,263.00 | 1,153,480,100 | 30,682,678.420 | 1.0399E8 |

| Dummy Variables | %age | |||

| Environmental Sensitivity-ES | 0.00 | 1.00 | 34.8% | |

| Multinational Subsidiary-MNSs | 0.00 | 1.00 | 14.2% | |

| N = 253 | ||||

| NTCSRDQn | NCS | NROA | ES | MNNs | NC | Dummy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NTCSRDQn | 1.000 | ||||||

| NCS | 0.339 ** | 1.000 | |||||

| NROA | 0.229 ** | −0.026 | 1.000 | ||||

| ES | 0.355 ** | 0.208 ** | 0.147 * | 1.000 | |||

| MNNs | 0.331 ** | 0.219 ** | 0.203 ** | 0.215 ** | 1.000 | ||

| NC | 0.058 | 0.269 ** | −0.315 ** | −0.039 | −0.075 | 1.000 | |

| Dummy | −0.005 | 0.001 | −0.007 | 0.000 | −0.012 | −0.003 |

| Variables | Prediction | Model 1 Experimental Model | Model 2 Control Model | Model 3 Full Model | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social Visibility Variables | |||||

| NCS | +Ve | 0.255 *** (0.052) | 0.233 *** (0.054) | Accepted | |

| NROA | +Ve | 0.161 *** (0.052) | 0.182 *** (0.054) | Accepted | |

| ES | +Ve | 0.246 *** (0.108) | 0.246 *** (0.108) | Accepted | |

| MNNs | +Ve | 0.225 *** (0.147) | 0.230 *** (0.147) | Accepted | |

| Control Variables | |||||

| NC | 0.074 (0.061) | 0.081 (0.056) | |||

| Dummy | 0.008 (0.117) | 0.013 (0.099) | |||

| (Constant) | −0.234 *** (0.083) | 0.027 (0.085) | −0.236 *** (0.083) | ||

| N | 253 | 253 | 253 | ||

| F-Value (Sig. Value) | 20.969 (0.000) | 0.694 (0.500) | 17.878 (0.000) | ||

| Adjusted R2 | 28.7% | 0.6% | 28.7% | ||

| Tolerance Values | 0.913–0.999 | 1.000–1.000 | 0.870–0.999 | ||

| VIF Values | 1.001–1.095 | 1.000–1.000 | 1.001–1.149 | ||

| Durbin-Watson | 2.179 | 2.144 | 2.146 | ||

| Prediction | Model 1 Experimental Model | Model 2 Control Model | Model 3 Full Model | Decision | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social Visibility Variables | |||||

| NCS | +Ve | 0.193 ** (0.078) | 0.168 ** (0.080) | Accepted | |

| NROA | +Ve | 0.190 ** (0.080) | 0.203 ** (0.080) | Accepted | |

| ES | +Ve | 0.246 *** (0.162) | 0.253 *** (0.162) | Accepted | |

| MNNs | +Ve | 0.799 (0.218) | 0.217 (0.218) | ||

| Control Variable | |||||

| NC | 0.082 (0.088) | 0.107 (0.079) | |||

| (Constant) | −0.226 ** (0.096) | 0.027 (0.085) | −0.233 ** (0.095) | ||

| N | 119 | 119 | 119 | ||

| F-Value (Sig. Value) | 10.857 (0.000) | 0.799 (0.373) | 9.075 (0.000) | ||

| Adjusted R2 | 25% | 0.7% | 25.5% | ||

| Tolerance Values | 0.892–0.942 | 1.000 | 0.887–0.931 | ||

| VIF Values | 1.062–1.121 | 1.000 | 1.074–1.127 | ||

| Durbin-Watson | 2.106 | 2.180 | 2.076 | ||

| Variables | Prediction | Model 1 Experimental Model | Model 2 Control Model | Model 3 Full Model | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social Visibility Variables | |||||

| NCS | +Ve | 0.308 *** (0.071) | 0.295 *** (0.075) | Accepted | |

| NROA | +Ve | 0.142 * (0.069) | 0.159 * (0.076) | Accepted | |

| ES | +Ve | 0.244 *** (0.147) | 0.242 *** (0.147) | Accepted | |

| MNNs | +Ve | 0.238 *** (0.202) | 0.241 *** (0.203) | Accepted | |

| Control Variable | |||||

| NL | 0.066 (0.086) | 0.043 (0.083) | |||

| (Constant) | −0.218 ** (0.086) | 0.043 (0.080) | −0.217 ** (0.086) | ||

| N | 134 | 134 | 134 | ||

| F-Value (Sig. Value) | 15.587 (0.000) | 0.582 (0.447) | 12.452(0.000) | ||

| Adjusted R2 | 30.5% | 0.3% | 31.1% | ||

| Tolerance Values | 0.918–0.963 | 1.000 | 0.752–0.933 | ||

| VIF Values | 1.039–1.090 | 1.000 | 1.072–1.330 | ||

| Durbin-Watson | 2.209 | 2.113 | 2.190 | ||

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ali, W.; Faisal Alsayegh, M.; Ahmad, Z.; Mahmood, Z.; Iqbal, J. The Relationship between Social Visibility and CSR Disclosure. Sustainability 2018, 10, 866. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10030866

Ali W, Faisal Alsayegh M, Ahmad Z, Mahmood Z, Iqbal J. The Relationship between Social Visibility and CSR Disclosure. Sustainability. 2018; 10(3):866. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10030866

Chicago/Turabian StyleAli, Waris, Maha Faisal Alsayegh, Zubair Ahmad, Zeeshan Mahmood, and Javed Iqbal. 2018. "The Relationship between Social Visibility and CSR Disclosure" Sustainability 10, no. 3: 866. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10030866

APA StyleAli, W., Faisal Alsayegh, M., Ahmad, Z., Mahmood, Z., & Iqbal, J. (2018). The Relationship between Social Visibility and CSR Disclosure. Sustainability, 10(3), 866. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10030866