The Relationship between Firm Size and Age, and Its Social Responsibility Actions—Focus on a Developing Country (Romania)

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Social Responsibility: From Large Companies to SMEs

1.2. Are There Differences in the Practices Regarding the Implementation of CSR in Developed versus Developing Countries?

1.3. Social Responsibility: From New to Old Companies

2. Theoretical Overview of Corporate Social Responsibility of SMEs

2.1. Institutional Setting. How Legal and Institutional Systems Influence the Propensity of Firms for CSR?

2.2. Social Responsibility in SMEs and Its Determinants

3. Research Method

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Level of Formalisation

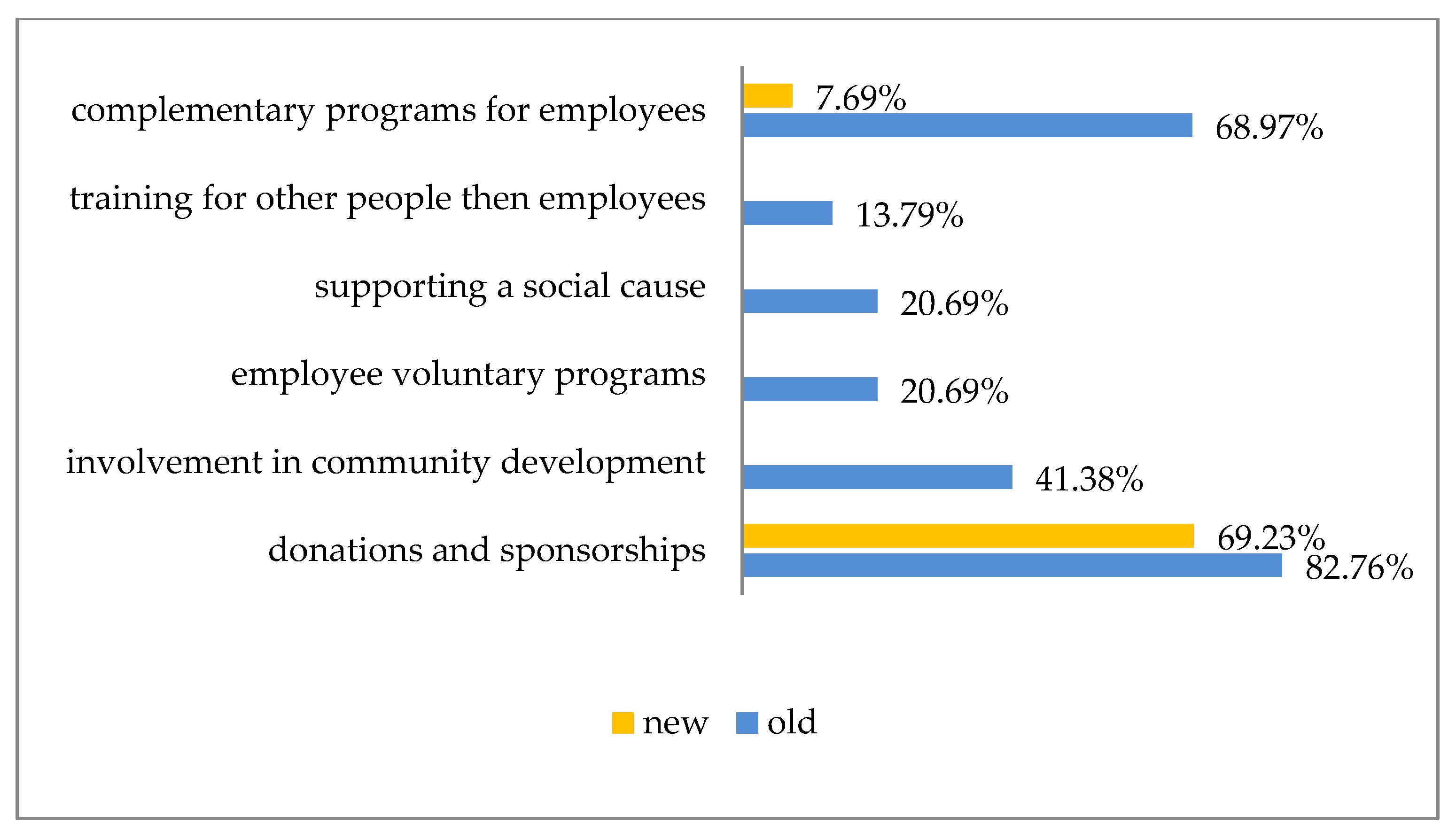

4.2. Types of Social Responsibility Actions

4.3. Attitudes of Managers Regarding the Role of Businesses to Promote Social Welfare

4.4. Impact of Different Factors on the Social Responsibility Type of Actions Scale

5. Conclusions and Limitations

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| Social welfare is solely the responsibility of governments. | Social welfare should be a priority for businesses. | ||||||||

| Area | Yes | No | |

| A | Sports | 1 | 0 |

| B | Culture | 1 | 0 |

| C | Environmental protection | 1 | 0 |

| D | Education | 1 | 0 |

| E | Community development | 1 | 0 |

| F | Charity | 1 | 0 |

| G | Charity (religious) | 1 | 0 |

| H | Others, please specify | 1 | 0 |

| Nature of the Action | 1. In the Past 12 Months | 2. In the Past 5 Years | |||

| Yes | No | Yes | No | ||

| A | Donations and sponsorship | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| B | Involvement in community development projects | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| C | Employee voluntary programs | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| D | Social marketing campaign | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| E | Supporting a social cause | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| F | Training for other people then its own employees | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| G | Complementary programs for employees | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| others, please specify... | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| Nature of the action | 1. Less than 215 Euros | 2. Between 215 and 2150 Euros | Between 2150 and 10,730 Euros | Over 10,730 Euros | |

| A | Donations and sponsorship | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| B | Involvement in community development projects | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| C | Employee voluntary programs | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| D | Social marketing campaign | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| E | Supporting a social cause | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| F | Training for other people then its own employees | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| G | Complementary programs for employees | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Others, please specify... | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| To a Very Small Extent | To a Small Extent | To a Large Extent | To a Very Large Extent | |

| Solving problems of the community | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Employee loyalty | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| A positive image of the company | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Client loyalty | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Financial gain | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Others, please specify … | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Partner | Yes | No | |

| A | NGO | 1 | 0 |

| B | Public administration institutions | 1 | 0 |

| C | Educational or research institutions | 1 | 0 |

| D | Others, please specify … | 1 | 0 |

- We rely on social or environmental diagnoses made by experts,

- We choose from the requests received from the beneficiaries,

- The company manager chooses the domains we are involved in.

| No. | Forms of Social Responsibility | Yes | No |

| 1. | Our company participates in activities which aim to protect and improve the quality of the natural environment. | 1 | 0 |

| 2. | Our company makes investments to create a better life for future generations. | 1 | 0 |

| 3. | Our company implements special programs to minimise its negative impact on the natural environment. | 1 | 0 |

| 4. | Our company targets sustainable growth which considers future generations. | 1 | 0 |

| 5. | Our company supports non-governmental organisations working in problematic areas. | 1 | 0 |

| 6. | Our company contributes to campaigns and projects that promote the well-being of society. | 1 | 0 |

| 7. | Our company encourages its employees to participate in voluntary activities. | 1 | 0 |

| 8. | Our company emphasises the importance of its social responsibilities to the society. | 1 | 0 |

| 9. | Our company policies encourage the employees to develop their skills and careers. | 1 | 0 |

| 10. | The management of our company is primarily concerned with employees’ needs and wants. | 1 | 0 |

| 11. | The managerial decisions related with the employees are usually fair. | 1 | 0 |

| 12. | Our company supports employees who want to acquire additional education. | 1 | 0 |

| 13. | Our company respects consumer rights beyond the legal requirements. | 1 | 0 |

| 14. | Our company provides full and accurate information about its products to its customers. | 1 | 0 |

| 15. | Customer satisfaction is highly important for our company. | 1 | 0 |

| 16. | Our company always pays its taxes on a regular and continuing basis. | 1 | 0 |

| 17. | Our company complies with legal regulations completely and promptly. | 1 | 0 |

References

- Szegedi, K.; Fülöp, G.; Bereczk, Á. Relationships between Social Entrepreneurship, CSR and Social Innovation: In Theory and Practice. Int. J. Soc. Behav. Educ. Econ. Bus. Ind. Eng. 2016, 10, 1421–1426. [Google Scholar]

- Tont, D.M.; Tont, M.D. An overview of innovation sources in SMEs. Oradea J. Bus. Econ. 2016, 1, 58–67. [Google Scholar]

- Rochlin, S.; Christoffer, B. Making the Business Case: Determining the Value of Corporate Community Involvement; Boston College Centre for Corporate Community Relations: Chestnut Hill, MA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Zadek, S.; Pruzan, P.; Evans, R. Building Corporate Accountability. Emerging Practices in Social and Ethical Accounting, Auditing and Reporting; Earthscan: London, UK, 1997; ISBN 978-1853834134. [Google Scholar]

- Raynard, O.; Forstater, M. Corporate Social Responsibility: Implications for Small and Medium Enterprises in Developing Countries; United Nations Industrial Development Organization: Vienna, Austria, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, H. Small Business Champions for Corporate Social Responsibility. J. Bus. Ethics 2006, 67, 241–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, L.J. CSR and small business in a European policy context: The five “C”s of CSR and small business research agenda. Bus. Soc. Rev. 2007, 112, 533–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweeney, L. Corporate social responsibility in Ireland: Barriers and opportunities experienced by SMEs when undertaking CSR. Corp. Gov. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2007, 7, 516–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaru, M.; Stoleriu, G.; Şandru, I. Social Responsibility Concerns of SMEs in Romania, from the Perspective of the Requirements of the EFQM European Excellence Model. Amfiteatru Econ. J. 2011, 13, 56–71. [Google Scholar]

- Aston, J.; Anca, C. Socially Responsible Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs): Guide on Integrating Social Responsibility Into Core Business. Project Co-Funded by the European Social Fund: Association of Romanian Exporters and Importers (ANEIR). 2011. Available online: https://www.astoneco.com/sites/default/files/public/downloads/downloads-smart/sme-guide-book-en.pdf (accessed on 3 January 2018).

- Obrad, C.; Petcu, D.; Ghergheş, V.; Suciu, S. Corporate Social Responsibility in Romanian Companies—Between Perceptions and Reality. Amfiteatru Econ. J. 2011, 13, 43–55. [Google Scholar]

- Visser, W. Corporate Social Responsibility in Developing Countries. In The Oxford Handbook of Corporate Social Responsibility; Crane, A., McWilliams, A., Matten, D., Moon, F., Siegel, D.S., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2008; pp. 473–499. ISBN 978-0199211593. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Millennium Development Goals Report 2006; United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Visser, W.; Matten, D.; Pohl, M.; Tolhurst, N. The A to Z of Corporate Social Responsibility; Wiley: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamali, D.; Lund-Thomsen, P.; Khara, N. CSR Institutionalized Myths in Developing Countries: An Imminent Threat of Selective Decoupling. Bus. Soc. 2017, 56, 454–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Morse, S.; Kambhamptati, U.; Li, B. Evolving Corporate Social Responsibility in China. Sustainability 2014, 6, 7646–7665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindgreen, A.; Swaen, V.; Campbell, T.T. Corporate Social Responsibility Practices in Developing and Transitional Countries: Botswana and Malawi. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 90, 429–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Withisuphakorn, P.; Jiraporn, P. The effect of firm maturity on corporate social responsibility (CSR): Do older firms invest more in CSR? Appl. Econ. Lett. 2015, 23, 298–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robbins, S.; Bergman, R.; Stagg, I.; Coulter, M. Management, 2nd ed.; Prentice Hall: Sydney, Australia, 2000; ISBN 978-1-442-50023-5. [Google Scholar]

- Pistoni, A.; Songini, L.; Perrone, O. The how and why of a firm’s approach to CSR and sustainability: A case study of a large European company. J. Manag. Gov. 2016, 20, 655–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Observatory of the European SMEs No. 4. European SMEs and Social and Environmental Responsibility; Office for Official Publications of the European Communities: Luxembourg, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, M. CSR in SMEs: Strategies, practices, motivations and obstacles. Soc. Responsib. J. 2011, 7, 490–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeppesen, S.; Kothuis, B.; Ngoc Tran, A. FOCALES 16: Corporate Social Responsibility and Competitiveness for SMEs in Developing Countries: South Africa and Vietnam; Agence Française de Développement: Paris, France, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Trencansky, D.; Tsaparlidis, D. The Effects of Company’s Age, Size and Type of Industry on the Level of CSR. The Development of a New Scale for Measurement of the Level of CSR. Master’s Thesis, Umeå School of Business and Economics, Umeå, Sweden, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wiklund, J. The Sustainability of the Entrepreneurial Orientation-Performance Relationship. Entrep. Theory Pract. 1999, 24, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blombäck, A.; Wigren, C. Challenging the importance of size as determinant for CSR activities. Manag. Environ. Qual. Int. J. 2009, 20, 255–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, S.; Wang, J.; Song, L. Determinants of Social Responsibility Disclosure by Chinese Firms; Discussion Paper 72; China Policy Institute, School of Contemporary Chinese Studies, University of Nottingham: Nottingham, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Zadek, S. The Path to Corporate Responsibility (From the December 2004 Issue). Available online: https://hbr.org/2004/12/the-path-to-corporate-responsibility (accessed on 12 December 2017).

- Visser, W. CSR 2.0. Transforming Corporate Sustainability and Responsibility; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; ISBN 978-3-642-40874-8. [Google Scholar]

- Vo, L.C. Corporate social responsibility and SMEs: A literature review and agenda for future research. Probl. Perspect. Manag. 2011, 9, 89–97. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, S. Supply chain specific? Understanding the patchy success of ethical sourcing initiatives. J. Bus. Ethics 2003, 44, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, J. Social responsibility and ethics: Clarifying the concepts. J. Bus. Ethics 2004, 52, 391–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castka, P.; Balzarova, M.A.; Bamber, C.J.; Sharp, J.M. How can SMEs effectively implement the CSR agenda? A UK case study perspective. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ Manag. 2004, 11, 140–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarkson, M.B.E. A stakeholder framework for analyzing and evaluating corporate social performance. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 92–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arlow, P.; Gannon, M. Social responsiveness, corporate structure, and economic performance. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1982, 7, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matten, D.; Crane, A. Corporate citizenship: Toward an extended theoretical conceptualization. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2005, 30, 166–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlsrud, A. How Corporate Social Responsibility is Defined: An Analysis of 37 Definitions. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ Manag. 2006, 15, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, T.; Vocht, C. Social role conceptions and CSR policy succes. J. Bus. Ethics 2007, 74, 363–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazzola, P.; Mella, P. Corporate Performance and Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR). A necessary choice? Econ. Azziendale Online 2006, 3, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, M.T. The Traditional Corporation, Corporate Social Responsibility and the ‘Outsourcing’ Debate. J. Am. Acad. Bus. Camb. 2005, 6, 91–97. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10536/DRO/DU:30032803 (accessed on 12 December 2017).

- Longo, M.; Mura, M.; Bonoli, A. Corporate social responsibility and corporate performance: The case of Italian SMEs. Corp. Gov. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2005, 5, 28–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matten, D.; Moon, J. “Implicit” and “Explicit” CSR: A Conceptual Framework for a Comparative Understanding of Corporate Social Responsibility. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2008, 33, 404–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Porta, R.; Lopez-De-Silanes, F.; Shleifer, A.; Vishny, R. Legal determinants of external finance. J. Financ. 1997, 52, 1131–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolk, A.; Perego, P. Determinants of the adoption of sustainability assurance statements: An international investigation. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2010, 19, 182–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amor-Esteban, V.; García-Sánchez, I.-M.; Galindo-Villardón, M. Analysing the Effect of Legal System on Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) at the Country Level, from a Multivariate Perspective. Soc. Indic. Res. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, J. Institutional analysis and the paradox of corporate social responsibility. Am. Behav. Sci. 2006, 49, 925–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirbag, M.; Wood, G.; Makhmadshoev, D.; Rymkevich, O. Varieties of CSR: Institutions and Socially Responsible Behaviour. Int. Bus. Rev. 2017, 26, 1064–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steurer, R. The role of governments in corporate social responsibility: Characterising public policies on CSR in Europe. Policy Sci. 2010, 43, 49–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger-Walliser, G.; Scott, I. Redefining Corporate Social Responsibility in an Era of Globalization and Regulatory Hardening. Am. Bus. Law J. 2018, 55, 167–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cominetti, M.; Seele, P. Hard soft law or soft hard law? A content analysis of CSR guidelines typologized along hybrid legal status. uwf UmweltWirtschaftsForum 2016, 24, 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besser, T.L.; Miller, N. Is the good corporation dead? The community social responsibility of small business operators. J. Socio-Econ. 2001, 33, 221–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wennekers, S.; Thurik, R. Linking entrepreneurship and economic growth. Small Bus. Econ. 1999, 13, 27–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mella, P.; Gazzola, P. Capitalistic Firms as Cognitive Intelligent and Explorative Agents. The Beer’s VSM and Mella’s Most Views. Manag. Dyn. Knowl. Econ. 2015, 3, 645–674. [Google Scholar]

- Badulescu, D.; Petria, N. Social Responsibility of Romanian Companies: Contribution to a “Good Society” or Expected Business Strategy? Ann. Univ. Oradea. Econ. Sci. 2013, 22, 590–600. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, A.; Thomsen, C. Investigating CSR communication in SMEs: A case study among Danish middle managers. Bus. Ethics 2009, 18, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, I.A.; Crane, A. Corporate social responsibility in small-and medium-size enterprises: Investigating employee engagement in fair trade companies. Bus. Ethics 2010, 19, 126–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousiolis, D.T.; Zaridis, A.D.; Karamanis, K.; Rontogianni, A. Corporate Social Responsibility in SMEs and MNEs. The Different Strategic Decision Making. Procedia Soc. Behv. 2015, 175, 579–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, R.W. Determinants of Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosure: An Application of Stakeholder Theory. Account. Org. Soc. 1992, 17, 595–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, G. Corporate Social and Financial Performance: An Investigation in the U.K. Supermarket Industry. J. Bus. Ethics 2001, 34, 299–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saveanu, T.; Abrudan, M.-M. Trends in the Social Responsibility Expenditures of Small and Medium Enterprises from Oradea. Mediterr. J. Soc. Sci. 2015, 6, 212–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Preuss, L.; Perschke, J. Slipstreaming the larger boats: Social responsibility in medium-sized firms. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 92, 531–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez-Carrasco, R.; Eugenia López-Pérez, M. Small & medium-sized enterprises and Corporate Social Responsibility: A systematic review of the literature. Qual. Quant. 2013, 47, 3205–3218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamali, D.; Zanhour, M.; Keshishian, T. Peculiar Strengths and Relational Attributes of SMEs in the Context of CSR. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 87, 355–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panwar, R.; Nybakk, E.; Hansen, E.; Pinkse, J. The effect of small firms’ competitive strategies on their community and environmental engagement. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 129, 578–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangi, F.; Meles, A.; Monferrà, S.; Mustilli, M. Does Corporate Social Responsibility Help the Survivorship of SMEs and Large Firms? Glob. Financ. J. 2018, in press. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1044028317304106 (accessed on 2 February 2018).

- Němec, O.; Surynek, A. Age management as a part of Corporate Social Responsibility. In Proceedings of the 9th International Days of Statistics and Economics, University of Economics, Prague, Czech Republic, 10–12 September 2015; pp. 1180–1190. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Centre for Corporate Social Responsibility (ACCSR). The CSR Manager in Australia. Research Report on Working in Corporate Social Responsibility; Australian Centre for Corporate Social Responsibility: Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Delai, I.; Takahashi, S. Sustainability measurement system: A reference model proposal. Soc. Responsib. J. 2011, 7, 438–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turker, D. Measuring Corporate Social Responsibility: A Scale Development Study. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 85, 411–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portney, P.R. The (Not So) New Corporate Social Responsibility: An Empirical Perspective. Rev. Environ. Econ. Policy 2008, 2, 261–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturdivant, F.D.; Ginter, J.L. Corporate social responsiveness: Management attitudes and economic performance. Calif. Manag. Rev 1997, 19, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boutin-Dufresne, F.; Savaria, P. Corporate Social Responsibility and Financial Risk. J. Invest. 2004, 13, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, H. A Critique of Conventional CSR Theory: An SME Perspective. J. Gen. Manag. 2004, 29, 37–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, T.; Cecilio, T.; Douglas, G.; Caeiro, S. Corporate sustainability reporting and the relations with evaluation and management frameworks: The Portuguese case. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 52, 317–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badulescu, A.; Badulescu, D.; Saveanu, T.; Hatos, R. SMEs and social responsibility: Does firm age matter? In Proceedings of the STRATEGICA Conference “Opportunities & Risks in the Contemporary Business Environment”, Bucharest, Romania, 20–21 October 2016; pp. 963–975, ISBN 978-606-749-181-4. [Google Scholar]

- Ayyagari, M.; Demirguc-Kunt, A.; Maksimovic, V. Small vs. Young Firms across the World: Contribution to Employment, Job Creation, and Growth. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper, No. 5631. 2011. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1807732 (accessed on 5 March 2018).

- Aga, G.; Francis, D.C.; Meza, J.R. SMEs, Age, and Jobs. A Review of the Literature, Metrics, and Evidence. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper, No. 7493. 2015. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2690632 (accessed on 5 March 2018).

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Young SMEs, Growth and Job Creation; OECD: Directorate for Science, Technology and Industry: Paris, France, 2014; Available online: https://www.oecd.org/sti/young-SME-growth-and-job-creation.pdf (accessed on 7 March 2018).

| No. | Name | Description | Measures |

|---|---|---|---|

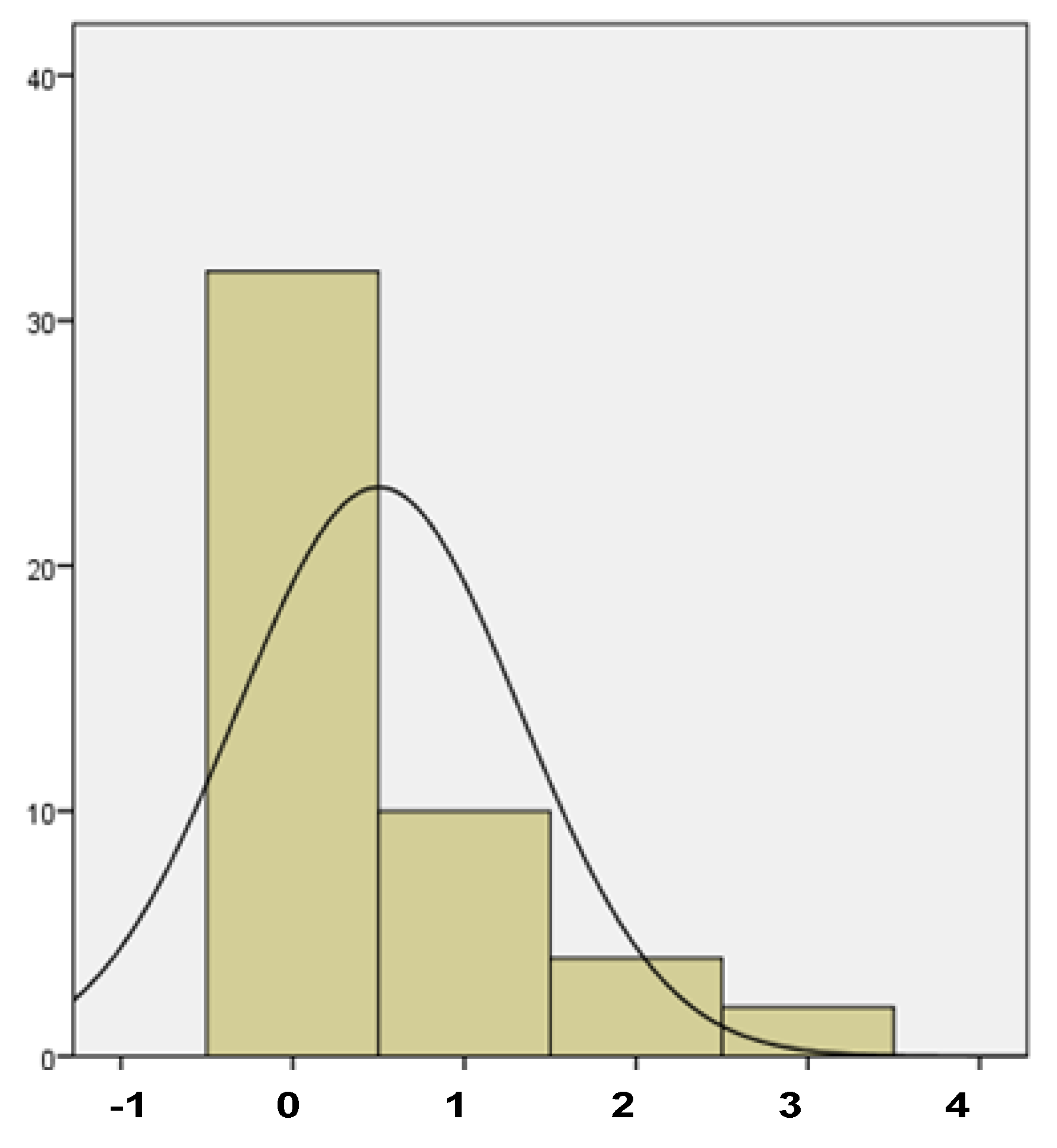

| 1 | The social responsibility action scale | Summative scale regarding the type of social actions undertaken by organisations based on question (Q)11_1: “Did your company organise the following activities: donations and sponsorship, involvement in community development projects, employee voluntary programs, social marketing campaigns, supporting a social cause, training for other people then its own employees, complementary programs for employees”. The answers were yes/no to each. | Mean: 1.73 Median: 1 Std. Deviation: 1.759 Skewness: 1.020 Kurtosis: 118 Minimum: 0 Maximum: 6 |

| 2 | Year of founding | “Year of establishment” (Q6) Indicates the year when the business started. This variable was also recoded in order to group firms: old—founded between 1991 and 2009, and new—founded between 2010 and 2012, based on the OECD and World Bank categorisations between new and old firms | Mean: 2004.17 Median: 2007 Std. Deviation: 6.982 Skewness: −0.774 Kurtosis: −0.992 Minimum: 1991 Maximum: 2012 |

| 3 | Number of employees | Indicates the number of employees at the time of response (Q3). | Mean: 61.21 Median: 9.00 Std. Deviation: 226.93 Skewness: 4.65 Kurtosis: 20.63 Minimum: 1 Maximum: 249 |

| 4 | Turnover (thousands of Euros) | Indicates the firm‘s turnover in the previous year (2015) (Q4). | Mean: 2084.56 Median: 196.37 Std. Deviation: 8579.54 Skewness: 4.671 Kurtosis: 20.74 Minimum: 34.87 Maximum: 42,313.90 |

| 5 | Level of formalisation | Mean scale based on the questions: “Are there social responsibility components in the profile of your firm‘s activity?” (Q7); “Is there explicit reference regarding social responsibility values or principles in your firm‘s strategic or operational documents?” (Q8) and “Is there a department or a person employed for dealing with CSR?” (Q9). The answers were yes/no to each. | Mean: 0.5000 Median: 0.0000 Std. Deviation: 0.82514 Skewness: 1.660 Kurtosis: 2.066 Minimum: 0.00 Maximum: 3.00 |

| 6 | Managers’ opinions regarding their responsibility towards collective welfare | Self-assessment on a 10-point scale for the question, “To what extent do you consider that social welfare is the responsibility of the business sector?”(Q6), where 1 means that social welfare is solely the responsibility of governments and 10 that the welfare of the society should be a priority for the business sector. | Mean: 4.73 Median: 5.00 Std. Deviation: 2.050 Skewness: −0.035 Kurtosis: −0.322 Minimum: 1 Maximum: 9 |

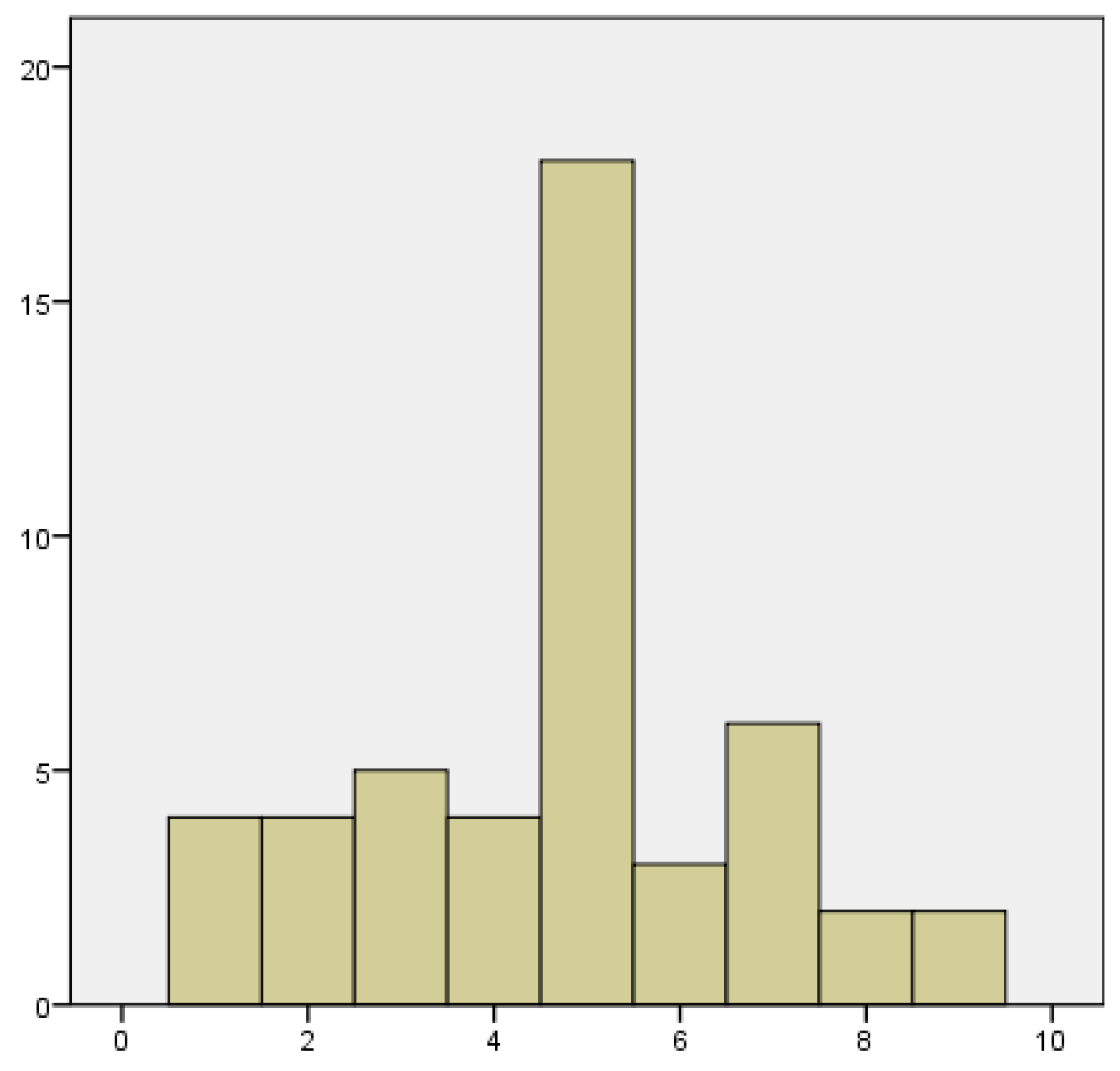

| 7 | Age of respondent | Indicates the age of the respondent (in years) (your age, in the final section, "Finally, we have some general questions“). | Mean: 42.85 Median: 40.00 Std. Deviation: 9.698 Skewness: 0.322 Kurtosis: −0.766 Minimum: 27 Maximum: 60 |

| Less than 215 Euros | Between 215 and 2150 Euros | Between 2150 and 10,730 Euros | Over 10,730 Euros | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Donations and sponsorship | 12.5% | 50.0% | 0.0% | 8.3% |

| Involvement in community development projects | 0.0% | 16.7% | 4.2% | 0.0% |

| Employee voluntary programs | 4.2% | 8.3% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| Social marketing campaign | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| Supporting a social cause | 8.3% | 4.2% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| Training for other people then its own employees | 0.0% | 4.2% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| Complementary programs for employees | 12.5% | 22.9% | 8.3% | 0.0% |

| Unstandardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | t | Sig. | Collinearity Statistics | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Std. Error | Beta | Tolerance | VIF | |||

| (Constant) | 57.459 | 55.031 | 1.044 | 0.303 | |||

| Year of founding | −0.028 | 0.027 | −0.109 | −1.016 | 0.316 | 0.705 | 1.419 |

| Turnover (thousands of euro) | 0.000 | 0.000 | −0.124 | −1.266 | 0.213 | 0.845 | 1.184 |

| Level of formalization | 1.430 | 0.231 | 0.669 | 6.181 | 0.000 | 0.687 | 1.457 |

| Managers’ opinions regarding their responsibility towards collective welfare | 0.155 | 0.096 | 0.181 | 1.618 | 0.113 | 0.643 | 1.556 |

| Age of respondent | −0.042 | 0.021 | −0.233 | −2.041 | 0.048 | 0.620 | 1.613 |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Badulescu, A.; Badulescu, D.; Saveanu, T.; Hatos, R. The Relationship between Firm Size and Age, and Its Social Responsibility Actions—Focus on a Developing Country (Romania). Sustainability 2018, 10, 805. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10030805

Badulescu A, Badulescu D, Saveanu T, Hatos R. The Relationship between Firm Size and Age, and Its Social Responsibility Actions—Focus on a Developing Country (Romania). Sustainability. 2018; 10(3):805. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10030805

Chicago/Turabian StyleBadulescu, Alina, Daniel Badulescu, Tomina Saveanu, and Roxana Hatos. 2018. "The Relationship between Firm Size and Age, and Its Social Responsibility Actions—Focus on a Developing Country (Romania)" Sustainability 10, no. 3: 805. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10030805

APA StyleBadulescu, A., Badulescu, D., Saveanu, T., & Hatos, R. (2018). The Relationship between Firm Size and Age, and Its Social Responsibility Actions—Focus on a Developing Country (Romania). Sustainability, 10(3), 805. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10030805