Abstract

By restoring forest ecosystems and fostering resilient and sustainable land use practices, Forest Landscape Restoration (FLR) contributes to climate change mitigation, adaptation and sustainable development as well as the protection of biological diversity and combating desertification. This integrative approach provides the opportunity for multiple wins, but it necessitates the management of complex institutional interactions arising from the involvement of multiple international organizations. Focusing on the pivotal aspect of financing, this article surveys the landscape of public international institutions supporting FLR and analyzes the effectiveness of existing mechanisms of inter-institutional coordination and harmonization. Methodologically, our research is based on a document analysis, complemented by participant observation of the two Bonn Climate Change Conferences in May and November 2017 as well as the Global Landscapes Forum in December 2017. We find that financial institutions have established fairly effective rules for the management of positive and negative externalities through the introduction of co-benefits and safeguards. The fact that each institution has their own safeguards provisions, however, leads to significant transaction costs for recipient countries. In the discussion, we thus recommend that institutions should refrain from an unnecessary duplication of standards and focus on best practice.

1. Introduction

Forest Landscape Restoration (FLR) is an action-oriented set of ideas about how to best achieve several forest-related international policy goals in a multiple-win approach. These goals include Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 15 on the sustainable use of terrestrial ecosystems [1] (p. 24), the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) Aichi Target 15 [2] to restore at least 15 percent of degraded ecosystems, the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) objectives regarding Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation in Developing Countries (REDD+) [3] and the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD) Land Degradation Neutrality (LDN) Project [4]. The fundamental aim of the FLR approach is to shift attention “away from simply maximizing tree cover to truly considering forest functions in the overall configuration of landscapes people depend on” [5]. As such, FLR has become a collective action frame for a wide variety of international actors to scale up forest restoration projects in an integrated landscape approach, based on national priorities and voluntary commitment. With FLR, stakeholders’ perceptions and activities can be directed towards “the process of regaining ecological functionality and enhancing human well-being across deforested or degraded forest landscapes”, considering “natural resource use (forests, energy, agriculture, water, etc.), conservation and livelihoods within a given area […] in an integrated manner” [5].

Large-scale forest restoration projects have already been undertaken in the 19th century [6]. Early examples of successful programs are the restoration of degraded heathland areas in mainland Denmark [7] and southern Sweden [8] as well as the creation of the Tijuca Forest and Paineiras conservation area in the 1860s in Brazil [9]. Prominent forest restoration initiatives in the 20th century include the countrywide reforestation effort in South Korea after the Korean War [10], the Kenya-based Green Belt Movement, founded in 1977 by Nobel Prize laureate Wangari Maathai [11], and natural regeneration programs in Costa Rica and Tanzania of the 1980s [12,13], ([14] p. 12). The international forest agenda was however largely dominated by conservation and sustainable management issues until the end of the 20th century. The concept of Forest Landscape Restoration (FLR) and its vision of multiple-wins were developed in 2000 at a workshop organized by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) and the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) in Spain [14] (p. 11). It was only after this that FLR began to gain momentum as a global movement. An important catalyst was the launch of the Bonn Challenge [15] in 2011 which calls for the restoration of 150 million hectares by 2020. This target was further extended by the New York Declaration on Forests in 2014 [16], approving an extra 200 million hectares by 2030 [17].

The integrative nature of the FLR approach corresponds to the increasing recognition in science as well as politics that global environmental problems need to be tackled in an integrated manner. Not only are different environmental problems such as climate change, desertification and biodiversity loss linked to each other, they also interact with social dynamics. Recent scientific approaches address environmental problems as embedded in complex and dynamic “coupled human and natural systems” [18] or “social-ecological systems” [19,20]. Their solution is assumed to require “systems integration” [21]. In the political realm, various attempts to coordinate the efforts of different international environmental organizations [22] (pp. 36–45) and the universal SDGs underline more integrated thinking.

The existing international institutional architecture, however, does not easily support integrated approaches like FLR. International regimes were set up to address specific issue areas. Over time, these regimes have developed considerable functional overlaps and new institutions have been founded for strategic reasons, further complicating the existing non-hierarchical network of co-governing organizations. The literature on regime complexes [23,24], regime complexity [25] and institutional fragmentation [26,27] addresses the question whether or under what conditions, situations of functional overlap will produce positive or negative governance effects and how institutional interaction can be managed [17,28]. For integrated approaches like FLR, this question poses special challenges because FLR governance is still in its infancy and requires a dynamic and process-oriented approach in contrast to the existing analytical and rather static forest governance approaches [29] (p. 271). The aim of this article is to study international organizations’ reactions to these challenges. We thereby focus on public financial institutions supporting FLR and map the institutional landscape. We analyze to what extent allocation criteria are compatible with the integrative vision of FLR.

The effective integration of different policy goals hinges on the management of the potential positive as well as negative externalities policy measures have on other issue areas. For this purpose, regulative as well as international financial and implementing institutions related to forest policy have specified co-benefits and established safeguard systems. While there is a growing body of literature discussing characteristics, opportunities and challenges of FLR as well as stakeholder engagement both at a global and national level [14,29,30,31,32,33,34,35], there has been less academic discussion on institutional interplay and rule-making with regard to FLR. We can however draw on a significant body of literature on related policy processes such as REDD+ and the CBD which addresses the challenges of institutional fragmentation [28,36,37] and operationalization of safeguards [38,39,40,41,42,43,44].

The result of our analysis is that all institutions have developed fairly efficient measures to manage positive and negative externalities of their activities for other policy fields related to FLR. While there are few variances between the different safeguard systems, each institution however cultivates its own system. This not only binds a lot of energy in the institutions themselves, but also creates high transaction costs for recipient countries, which often deal with several institutions and consequently requirements and procedures in parallel.

2. Theoretical Framework, Materials and Methods

To analytically grasp the growing institutional density [45] or complexity [46] of international relations, scholars have worked out concepts like regime complexes [23,24], regime complexity [25] or institutional fragmentation [26,27]. All of them seek to better understand the impact of increasing institutional interlinkages “in the absence of hierarchical coordination on the strategic behavior of state actors and on the governance of specific issue areas” [37] (p. 3), (see also [47,48]).

Functional overlap between institutions can be deliberately created by states which are dissatisfied with the regulatory work of a specific organization and want to shift rule-making to another existing organization or even create a new organization [49] (p. 297). Unintentional functional overlap occurs if an organization is created for functional reasons in an existing issue area already covered by other organizations [49] (p. 298). With regard to climate finance, the establishment of the Green Climate Fund (GCF) could be an example as the funding to be managed by the GCF has so far predominantly been covered by the World Bank. Finally, functional overlap can also occur independently from member states’ intentions if an international organization pursues a mission creep, meaning that the organization itself expands its regulatory competencies [49] (p. 298), [50].

Complexes of international institutions with functional overlap present states with strategic opportunities for forum-shopping [24,51] and regime-shifting [52]. Some scholars [53,54,55,56] argue that functional overlap and institutional interplay are “potentially problematic” [56] (p. 29) and harm the effectiveness of global governance because states strategically use institutional fragmentation to pursue their parochial interests. Consequently, rules-based cooperation is undermined by the evolution of contradictory rules and the performance of international organizations is restricted.

This position is opposed by Gehring and Faude [57] who develop a functional argumentation based on differentiation theory and institutional ecology. They attribute more positive features to the functional overlap among regulative international institutions and consider institutional fragmentation as a “rational response to the increasing complexity of society” [47] (p. 120). Gehring and Faude argue that states as members of multiple overlapping institutions have a general interest in coherent rules and institutional complementarity and take this into account “when determining their behavior within either of these institutions” [57] (p. 471). Especially when the distribution of power between states is balanced, they expect the emergence of sophisticated patterns of co-governance [57] (p. 481), (see also: [58] (pp. 374–375)). “In the absence of inter-institutional negotiations and a written contract” [57] (p. 482), Gehring and Faude hold that a division of labor will spontaneously evolve in a process of mutual adaptation. Faude further argues that international organizations themselves have an interest in resolving functional overlap because this exposes them to inter-organizational competition [49] (p. 300), (see also: [25,59,60]). He expects organizations to react by specializing in specific issues, functions or policy instruments, but also considers the assimilation of rules among institutions as an alternative solution [49] (pp. 301–303).

Holzscheiter [61] (p. 323) adds a constructivist perspective to the debate. She argues that inter-organizational relations and cooperative structures are a result of influential and contested global norms. The norms which she reconstructs—similar to the functional logic of Faude and Gehring—prescribe harmonization of rules and inter-organizational coordination, including division of labor, as a precondition for effective global governance [61] (pp. 335–336). In contrast to Faude and Gehring, who explicitly delimit their argument to regulative international institutions [57] (pp. 493–494), Holzscheiter focuses on organizations in the global health sector which have more operative functions [61] (p. 335). In this context, functional overlap is problematic not only because it gives countries opportunities for forum shopping and might lead to contradictory rules, but also because a lack of coordination can easily lead to a duplication of structures and efforts, which results in high transaction costs [61] (p. 339), [62,63,64]. Holzscheiter’s constructivist perspective allows for an analysis of unintended or irrational effects of inter-organizational cooperation. She argues that institutionalization of such a cooperation often leads to hypercollective action [65] which neither increases efficiency nor reduces institutional structures. Instead, the proliferation of cooperative structures can increase transaction costs [61] (pp. 327–328).

FLR as a collective action frame and related institutional initiatives such as the Global Partnership on Forest and Landscape Restoration (GPFLR) and the Bonn Challenge are premium examples of actors’ awareness of a functional overlap between the CBD, UNFCCC and UNCCD. They seek to streamline related restoration goals in an integrated way and to establish an institutional arrangement that creates win-win-win solutions in terms of the protection of biodiversity and the global climate while at the same time promoting and supporting sustainable livelihoods [15]. The funding of FLR activities is central to the realization of the conventions’ goals. However, as the financing for REDD+ has already shown [37], both functionally overlapping rule-making and diverse allocation principles as well as competition for funds make the implementation burdensome for those seeking to realize and manage projects on the ground.

In the following section, we will map the diverse funding mechanisms in place and analyze their safeguards and co-benefits rules. The aim is to analyze whether there is—or is the potential for—inter-organizational coordination to streamline FLR into international forest financing, resulting in the harmonization of rules among the different issue areas and organizations to better address FLR governance challenges. In addition to coordination and harmonization efforts at the operative level of financial institutions, we also consider relevant decision at the regulative level of international negotiating bodies. We examine whether inter-institutional coordination and harmonization are produced by processes of mutual adjustment or by negotiated agreements, whether they take the form of functional differentiation or assimilation of rules, and whether they result in increased effectiveness, coherent rules and low transaction costs or have negative impacts.

The analysis is methodologically rooted in a qualitative research agenda. Because the objective of this article is to study the different organizations involved in FLR financing and their respective safeguards and co-benefits rules, this analysis is based on a document analysis of UN and World Bank documents as well as secondary literature on FLR related financing and rule-making. This document analysis is further enriched by insights gained from participant observation of the two UNFCCC climate negotiations in May (SBI, SBSTA) and November (COP 23) as well as the Global Landscapes Forum in December 2017, all taking place in Bonn, Germany.

3. Results

It is consensus among those involved in international efforts to protect and restore forests that dedicated multilateral public finance will only be able to supply a minor amount of the money needed. It is thus essential not only to attract some niche private investments but to green regular flows of private and public money, most importantly in the area of agriculture [66,67]. However, big multilateral funds—especially climate funds—play a central role in setting standards, catalyzing other investments, and fostering the reform of national regulations. We therefore focus on the Global Environment Facility (GEF), the Green Climate Fund (GCF), the UN-REDD Programme and the World Bank climate funds.

The GEF has existed since 1994 and is the major financial mechanism of the CBD and the UNCCD. It is also one of the most important sources of REDD+ finance. Within its integrated strategy of Sustainable Forest Management (SFM), the GEF provides a specific funding window for FLR [68] (p. 163). The GCF was set up in 2010 as an additional UNFCC funding mechanism and assists developing countries in their climate change mitigation and adaptation activities. It has recently announced a pilot program for REDD+ results-based payments [69] and also provides support for REDD+ readiness and implementation activities [70]. While the GCF has no special funding window for FLR, the “landscape approach” is explicitly mentioned as an important instrument for “coordinating agriculture, restoration of degraded lands, sustainable forest management, and conservation in an integrated manner […] [which] applies to virtually all eligible REDD-plus activities” [70] (p. 9).

The UN-REDD Programme, a UN collaborative program established in 2008, supports countries in preparing and implementing REDD+ strategies. It is jointly managed by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). In 2014, UNEP and IUCN announced a collaboration [71] which aims at making FLR knowledge and restoration opportunity assessment tools available to UN-REDD Programme countries. Initial steps included the institution of an FLR helpdesk and pilot projects in several selected countries.

The World Bank not only plays a central role in multilateral development finance, but also administers three important climate funds which support REDD+ activities: The Bio Carbon Fund (BioCF), operational since 2004, the Forest Carbon Partnership Facility (FCPF), operational since 2008, and the Forest Investment Program (FIP), operational since 2009. The BioCF in its current Initiative for Sustainable Forest Landscapes (ISFL) follows an integrated landscape approach, supports large-scale land-use change programs and pilots a carbon accounting methodology which assesses overall emissions reductions from land-use change including restoration activities [72]. In comparison, the FCPF is more narrowly focused on REDD+ [73]. The FIP is intended to pilot or scale-up innovative approaches to forests as a climate change issue. Similar to the BioCF it aims at large-scale projects which result in nationally significant shifts in forest management practices [74] (p. 5). An increasing amount of FIP finance goes to “landscape approaches” [75] (p. 4). In its overall Forest Strategy, published in 2002 [76], and its Forest Action Plan for 2016–2020 [77], the World Bank proclaims its intention to move beyond small-scale forest projects to a programmatic approach, which supports forest-smart national development policies. One important feature of this are integrated finance packages which combine funding from the World Bank Group development agencies with money from the climate change trust funds administered by the World Bank as well as other sources [77] (pp. 53–55). An “integrated landscape approach” [77] (p. 14) is supposed to guide all World Bank forest interventions [77] (p. 28).

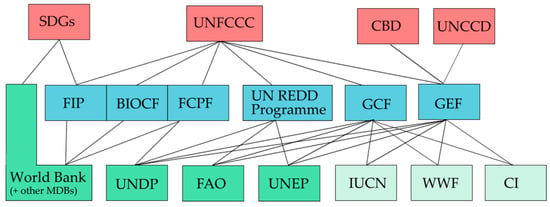

In the overall landscape of international institutions contributing to the governance of FLR (see Figure 1), these funds constitute a middle layer between regulative institutions and implementing institutions. The former include the UNFCCC, the CBD, the UNCCD, and the SDGs. The latter comprise the World Bank and other multilateral development banks (MDBs) as well as several UN subsidiary organizations and international non-governmental organizations (NGOs). Thus, the World Bank, several regional MDBs, the FAO, UNDP, UNEP, Conservation International (CI), IUCN and the WWF are accredited among others as implementing agencies to both the GEF and the GCF. The Inter-American Development Bank (IADB) and UNDP also serve alongside the World Bank as delivery partners for the FCPF. The FIP is implemented by the World Bank together with other MDBs. The BioCF is implemented by the World Bank. UNDP, UNEP and FAO together implement the UN-REDD Programme. Notably, the financing landscape for FLR does hardly differ from the one for REDD+. However, for the more integrative approach of FLR, the issue of cooperation and harmonization between these institutions needs to be reconsidered.

Figure 1.

The institutional landscape around multilateral public funds supporting FLR activities: The financial institutions are displayed in blue, the regulative institutions in red, the governmental implementing agencies in green, and the non-governmental implementing agencies in light green (own illustration).

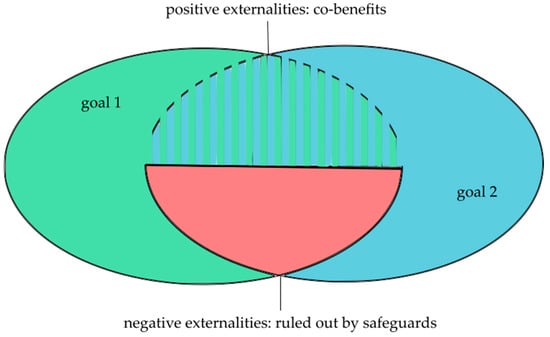

The need for inter-institutional coordination and harmonization of rules in the area of FLR arises not because the goals of the relevant regulatory organizations inherently contradict each other, but because their operationalization in specific projects can produce—positive or negative—externalities for other areas of action. Throughout the institutional landscape relevant for FLR, two instruments for the harmonization of rules have evolved, which we will analyze in the following: through the specification of co-benefits, institutions intend to provide for positive externalities and through the establishment of safeguard systems, they seek to avoid negative externalities. In reality, the distinction between the two instruments is not as clear-cut as depicted here. Often, safeguard standards also stipulate some areas where co-benefits are to be sought. Their central purpose, however, is to “safeguard” against unintended negative consequences, while the purpose of co-benefits is to generate other benefits in addition to the core objective. The difference between the two instruments as ideal types is illustrated by Figure 2.

Figure 2.

How safeguards and co-benefits address externalities: Safeguards rule out actions in the red area, but permit all actions, which are fully or partly green (for institutions aiming at goal 1) or blue (for institutions aiming at goal 2). A co-benefits approach focuses on the smaller green-blue striped area (own illustration).

3.1. Specification of Co-Benefits

At the level of regulative institutions, co-benefits are not specified in a very concrete or binding manner, but institutions seek to integrate goals from other issue areas into their programs. Most vigorously, the SDGs have brought together economic, social and environmental dimensions of global development. In the preamble of the Agenda 2030, the “protect[ion of] the planet from degradation, including through […] sustainably managing its natural resources and taking urgent action on climate change” comes second, right after the determination to “end poverty and hunger, in all their forms and dimensions” [1]. SDG 13 addresses climate change mitigation and adaptation and, in SDG 15, countries resolve to “protect, restore and promote sustainable use of terrestrial ecosystems, sustainably manage forests, combat desertification, and halt and reverse land degradation and halt biodiversity loss” [1] (p. 14).

The UNFCCC Paris Agreement “aims to strengthen the global response to the threat of climate change, in the context of sustainable development and efforts to eradicate poverty” [78] (§ 2). In 2010, REDD+ parties affirmed at the 16th Conference of Parties (COP 16) in Cancún that REDD+ actions should be “consistent with the objective of environmental integrity” and “implemented in the context of sustainable development and reducing Poverty” [79] (p. 26).

The CBD Strategic Plan for Biodiversity 2011–2020 emphasizes that “[b]iological diversity underpins ecosystem functioning and the provision of ecosystem services essential for human well-being […] and is essential for the achievement of the Millennium Development Goals, including poverty reduction” [2] (p. 6). Strategic goal D is to “enhance the benefits to all from biodiversity and ecosystem services” [2] (p. 9). Aichi target 14 aims to restore ecosystems that provide essential services, taking into account the needs of women, indigenous and local communities as well as the poor and vulnerable by 2020. Aichi target 15 sets the goal to restore 15 percent of degraded ecosystems by 2020 with the rationale of contributing to climate change mitigation and adaptation and to combating desertification [2] (p. 9).

In its ten-year strategic plan 2018–2028, the UNCCD lists the improvement of the living conditions of affected populations as its second strategic objective right after the improvement of the conditions of affected ecosystems. Biodiversity and climate change are addressed under strategic objective number 4: “To generate global environmental benefits through effective implementation of the UNCCD” [80] (pp. 3–4).

Financing institutions adopt these proclamations of integrated aims from the regulative institutions they serve and make them effective through the more concrete specification of co-benefits recipient countries need to include in their funding proposals. If financial institutions are connected to several regulative institutions, this can foster an enhanced integration of goals as exemplified by the GEF, which has since 2000 promoted projects that cut across several of its convention-related focal areas and integrated funding lines like the GEF-6 SFM strategy [81] (p. 7). The objective of the sub-program on FLR is to “reverse the loss of ecosystem services within degraded forest landscapes” [68] (p. 171). Success is measured in terms of the “area of forest resources restored in the landscape” in hectare [68] (p. 171). Poverty reduction and livelihood enhancement are mentioned as goals of the SFM strategy alongside biodiversity conservation, climate change mitigation, and combating desertification [68] (pp. 153–158), but not translated into indicators.

Member countries are not as enthusiastic about integrated funding lines as the GEF Secretariat, because it is unclear how integrated approaches count in member countries’ commitments under the Rio Conventions. Furthermore, ministries want to have clear budgets for their respective policy fields, which is not necessarily compatible with the idea of policy integration. Representatives of the Rio Conventions, too, lobby for clear budgets allocated to the implementation of their programs, which indicates an inter-institutional competition for funds [82,83]. GEF Programming Directions are consequently a compromise between the integrative ambitions of the GEF Secretariat and the needs of member countries. The Secretariat’s first draft for the GEF-7 Programming Directions, for example, focused on 14 integrated Impact Programs including one on Landscape Restoration [84]. After discussions with stakeholders at the first replenishment meeting in March 2017, the Secretariat revised this draft. As a result, the focus was shifted back to focal area strategies and the number of Impact Programs was reduced to four. FLR became part of a new Impact Program on Food Systems, Land Use and Restoration. In addition, it will continue to be an important instrument within the Impact Program on SFM. In GEF-7, the focus of the SFM Impact Program will be on three selected ecosystems (the Amazon, the Congo Basin, and important drylands) [85].

The core goals of the GCF are climate change mitigation (measured in tons of carbon dioxide equivalent reduced) and adaptation (measured in total number of beneficiaries and number of beneficiaries relevant to population) [86] (p. 7). The fund’s Initial Investment Framework contains further criteria for funding decisions. These include the projects’ “sustainable development potential” in terms of environmental co-benefits (e.g., in the areas of eco-system services and biodiversity conservation), social co-benefits (e.g., in the areas of health and safety, education, good governance and culture), economic co-benefits (e.g., in the areas of job creation, poverty alleviation, and economic development), and gender-sensitive development impact (with regard to correcting existing inequalities in climate change vulnerability) [87]. In the GCF’s pilot project on REDD+ results-based payments, the provision of information on non-carbon benefits is optional. However, non-carbon benefits can improve the overall scoring of funding proposals with regard to project selection [88] (p. 19). This is in accordance with UNFCCC decisions on REDD+, which recognize the importance of non-carbon benefits [89] (p. 26) but leave their consideration at the discretion of countries [90] (p. 15).

The UN-REDD Programme closely follows UNFCCC guidance. Accordingly, it supports countries to enhance non-carbon benefits “where desired” [91] (p. 13). Nonetheless, the declared overall development goal of the Programme is to “reduce forest emissions and enhance carbon stocks from forests while contributing to national sustainable development” [91] (p. 7) and its safeguard standards address positive externalities for poverty reduction and sustainable development, including biodiversity protection and other environmental and natural resource management objectives [92] (p. 6).

The World Bank’s Forest Action plan is designed to address the bank’s core mission “to end extreme poverty and boost shared prosperity in a sustainable manner” [77] (p. vii) in an integrated way. The livelihood value and economic potential of forests plays the central role in the Forest Action Plan, but climate change adaptation and mitigation are also understood as genuine goals of World Bank activities. The Forest Action Plan is aligned with the World Bank’s Climate Change Action Plan and supposed to serve the “global forest agenda” [77] (p. 2), which includes the SDGs, the UNFCCC Paris Agreement and the Bonn Challenge as well as the United Nations Forum on Forests (UNFF) agenda. The Forest Action Plan’s second focus area of forest-smart interventions in other sectors is intended to address trade-offs between different land uses and to deliver integrated solutions for complex developmental problems. Emphasis is placed on comprehensive ex-ante analysis of possible trade-offs and synergies [77] (p. 29).

Reflecting the overall World Bank approach, non-carbon benefits are an integral part of the FCPF emissions reductions program as well as BioCF and FIP programs. The FCPF and the BioCF list improved local livelihoods, transparent and effective forest governance structures, securing of land tenure, protection of biodiversity and/or other ecosystem services as desirable co-benefits [93] (p. 25), [94] (p. 7). The FIP focuses on co-benefits for forest-dependent communities, including indigenous peoples, the protection of biodiversity and the adaptive capacity of forest ecosystems and their human inhabitants. Both in the BioCF [95] (p. 8) and the FIP [96] (pp. 5–6) countries are required to report on the number of people having received livelihood benefits.

3.2. Establishment of Safeguard Systems

At the level of regulative institutions, the UNFCCC COP 16 in 2010 in Cancún has adopted a set of broad but not very detailed safeguards for REDD+ activities [79] (pp. 26–27). The CBD COP 9 in Bonn in 2008 took up the issue of potential REDD+ impacts on biodiversity and an Ad Hoc Technical Expert Group on Biodiversity and Climate Change (ADTEG-BDCC) was established, which produced a report on Connecting Biodiversity and Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation, published in 2009 [97]. However, the report was not officially endorsed by the CBD COP. Even though UNFCCC negotiators were unwilling to consider the report or include very specific biodiversity provisions into REDD+ safeguards, the report nevertheless raised attention for the issue of REDD+ impacts on biodiversity. At the CBD COP 10 in Nagoya in 2010, important REDD+ recipient countries resisted any formal input to the UNFCCC, but the COP mandated the CBD Secretariat to provide advice on the application of REDD+ safeguards in a biodiversity-protecting manner and to convene an expert workshop on the issue together with the UNFCCC. In addition, the CBD organized three regional workshops. [98] (pp. 15–16). The resulting recommendations [99] were adopted as voluntary guidance for countries by the CBD COP 11 in Hyderabad in 2012 [100] (p. 212). Binding biodiversity safeguards for REDD+ were prevented by several recipient countries, which had no interest in strong and specific regulations. In the UNFCCC as well as the CBD, they raised the argument, that the institution had no mandate to deal with issues of the other institution [98] (pp. 15–16), [42] (pp. 1–2). This case illustrates how complicated and challenging inter-institutional cooperation and coordination can be when regulative institutions try to find ways to better integrate policies and related regulations. Legal aspects and member countries’ interests and commitment play a decisive role in the pursuit of more integrated approaches.

At the level of financing and implementing institutions, each organization has its own safeguards policy, which all of its projects need to comply with. There are some differences between these policies, but diversity is limited by the fact that all of them are directly or indirectly informed by the World Bank safeguards. These have become a kind of de-facto minimum standard. The World Bank has recently updated its safeguards policy. The new Environmental and Social Framework (ESF) [101], which is 148 pages long, becomes effective in January 2018 and contains 10 Environmental and Social Standards, which are—in contrast to the UNFCCC Cancún safeguards—spelled out in quite some detail.

The GCF is still in the process of developing its own safeguard standards. It has adopted interim safeguards based on the 2012 Performance Standards for Environmental and Social Sustainability of the International Finance Corporation (IFC) [102], the World Bank daughter for engagement with the private sector [86] (p. 3). While geared more to private sector project partners, the 2012 IFC performance standards are otherwise more or less identical with the 2018 World Bank ESF. The GEF’s Agency Minimum Standards on Environmental and Social Safeguards adopted in 2012 [103] are modeled very closely on the 2005 World Bank Environmental and Social Safeguard Policies [104], which are still much less systematic in their coverage than the new World Bank ESF.

The UN-REDD Programme’s Social and Environmental Principles and Criteria (SEPC) adopted in 2012 build on the UNFCCC Cancún Safeguards as well as the safeguard policies of the three implementing agencies [92] (p. 2). Considering that the FAO, the UNEP and the UNDP are accredited to the GEF and the GCF, which require their implementing agencies to meet standards modeled on the World Bank safeguards, their respective safeguards systems can be assumed to be consistent with (at least the 2005) World Bank standards. Nevertheless, the UN-REDD Programme SEPC is unique in its integration of the UNFCCC Cancún safeguards.

The other financial institutions funding REDD+ activities have found different ways to address the Cancún safeguards (see Table 1). In its Methodological Framework for the Carbon Fund, the FCPF requires Emissions Reductions Proposals to “promote and support” the Cancún safeguards in addition to “meet[ing]” the World Bank safeguards [93] (p. 18). Tasked with clarifying how the two standards relate to each other, the FCPF management team concluded that the “application of the World Bank’s safeguards […] should be sufficient to ensure that the World Bank’s safeguards successfully promote and support the UNFCCC safeguards for REDD+” [105] (p. 1). The World Bank can revert to this position also with regard to the FIP which, too, requires implementing MDBs to ensure projects’ consistency with UNFCCC decisions on safeguards [106] (p. 8). The BioCF does not explicitly require application of the Cancún safeguards, but in the ISFL Emissions Reductions Program Requirements, it is nevertheless pointed out that UNFCCC REDD+ safeguards will be satisfied through the application of the World Bank safeguards [94] (p. 5).

Table 1.

Safeguards required by financial institutions supporting FLR.

Contrary to the World Bank’s assessment, the GCF concludes that “there are key differences between the Cancun safeguards and the GCF environmental and social safeguards standards” [69] (p. 8). In its pilot program for REDD+ results-based payments, the GCF has split the task of complying with both standards between actors: While it is the responsibility of the GCF accredited entities implementing REDD+ projects to describe how the GCF safeguards have been met, the countries are responsible for demonstrating how the Cancún safeguards have been addressed [69] (p. 9). The GEF, which does not have a specific REDD+ program, does not require projects to meet the Cancún safeguards.

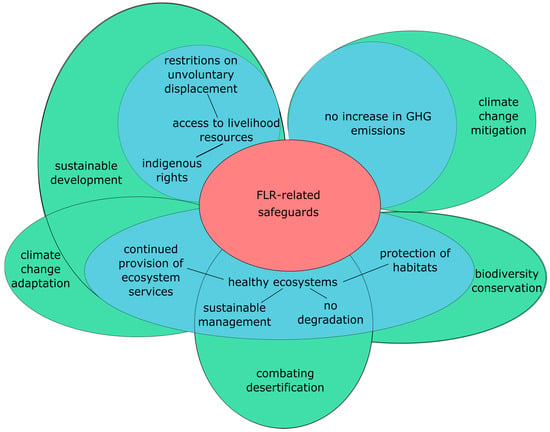

All of the safeguard standards cover a wide array of topics including provisions on good governance, stakeholder engagement, and the protection of human rights and security as well as obligations to avoid negative (and to some extent foster positive) externalities for environmental integrity and sustainable development. With regard to negative externalities for FLR, three clusters of provisions are most important: (1) provisions addressing GHG emissions, which prevent negative externalities for the UNFCCC goal of climate change mitigation; (2) provisions aiming to protect healthy eco-systems and to prevent negative externalities for the CBD aim of biodiversity protection (if they protect habitats), the UNCCCD mission of combating desertification (if they halt degradation and foster sustainable management of natural resources), and the UNFCCC goal of climate change adaptation as well as the SDG project of sustainable development (as they ensure people’s continued access to ecosystem services); and (3) provisions guaranteeing access to livelihood resources by protecting indigenous rights and restricting involuntary resettlement to prevent negative externalities for sustainable development as enshrined in the SDGs (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

FLR-related safeguard provisions and how they relate to goals in different issue areas (own illustration).

Surprisingly, provisions against project-related increases in GHG-emissions are not part of the 2005 World Bank safeguards (or those of the GEF). These were integrated into the World Bank safeguard systems in 2012 when IFC performance standards were set up. There and in the 2018 World Bank ESF, climate pollutants are considered within the standard on Resource Efficiency and Pollution Prevention and Management. The stated objective is to “avoid or minimize project-related emissions of short and long-lived climate pollutants” [101] (p. 61). Due to climate change mitigation being the primary goal of REDD+, the Cancún safeguards and the UN-REDD SPEC focus on the more specific risk of reversals of emissions reductions achieved in the forest sector or their displacement to other forest or non-forest carbon stocks [79] (p. 27), [92] (p. 7).

Safeguards for the protection of healthy ecosystems are developed most with regard to biodiversity conservation. Provisions against land degradation are mainly treated as an aspect of habitat protection. Sustainable forest management and eco-system services are not as prominent as biodiversity concerns, but nevertheless receive increased attention.

The World Bank 2005 safeguards contain standards on Natural Habitats and on Forests (the GEF safeguards combine them under the heading of Protection of Natural Habitats). These standards focus on the protection of forests and other natural habitats from degradation or conversion, including conversion to planted forests. Plantations need to be designed to prevent the introduction of invasive species [107] (pp. 1–2) [108] (p. 1), and commercial harvesting operations must follow standards of “responsible forest management” [107] (p. 2). The maintenance of ecological functions is mentioned as an aim in the standard on Natural Habitats [108] (p. 1) and the standard on Forests specifies that forest restoration activities shall maintain or enhance ecosystem functionality [107] (p. 1). GEF standards are more stringent than the 2005 World Bank standards with respect to the introduction of potentially invasive, non-indigenous species [103] (p. 5).

In the 2018 World Bank ESF (as well as the 2012 IFC performance standards), the issues of natural habitats and forests are integrated into a general standard on Biodiversity Conservation and Sustainable Management of Living Natural Resources. Protection is extended to modified habitats with significant biodiversity value and restrictions on the introduction of potentially invasive alien species are strengthened [101] (pp. 102–103). Commercial production and harvesting of living natural resources now needs to follow standards of “sustainable management” [101] (p. 103). Reflecting its connection to human livelihoods, the issue of eco-system services has moved to the standard on Community Health and Safety. More emphasis is put on avoiding negative impacts on ecosystem services [101] (p. 69).

In the same way but less detailed as the World Bank standards, the Cancún safeguards call for REDD+ activities to be “consistent with the conservation of natural forests and biodiversity, ensuring […] [they] are not used for the conversion of natural forests, but are instead used to incentivize the protection and conservation of natural forests and their ecosystem services” [79] (p. 26). While this is not part of the provisions labeled as safeguards, the UNFCCC decisions taken in Cancún 2010 stipulate that REDD+ activities shall “promote sustainable management of forests” [79] (pp. 26–27). Elaborating on the Cancún safeguards, the UN-REDD SEPC requires REDD+ programs to “protect natural forests from degradation and/or conversion” [92] (p. 6) through REDD+ activities and to avoid negative impacts on biodiversity. REDD+ programs shall not involve the conversion of natural to planted forest, unless as part of forest restoration. They shall “maintain and enhance multiple functions of forests including conservation of biodiversity and provision of ecosystem services” [92] (p. 7) through land-use planning and forest management and also “avoid or minimize adverse impacts on non-forest ecosystem services and biodiversity” [92] (p. 7).

With regard to negative externalities for people’s livelihoods, two issues are addressed: involuntary resettlement and indigenous rights. The World Bank 2005 (and the GEF) safeguards contain rules on avoiding, minimizing and mitigating restrictions in access to land and involuntary resettlement. Affected people shall be assisted in enhancing or at least restoring their livelihoods [109]. The most important strengthening in the World Banks 2018 ESF is a prohibition of forced evictions [101] (p. 77). The Cancún safeguards do not address the issue, but the UN-REDD SEPC even goes beyond World Bank standards by stipulating that countries should “ensure there is no involuntary resettlement as a result of REDD+” [92] (p. 5).

The World Bank standards on Indigenous peoples require full respect for indigenous people, their rights and culture. Adverse impacts on them are to be avoided, minimized and mitigated including through provisions on culturally appropriate social and economic benefits. While the 2005 World Bank standards [110] only ask for Free, Prior and Informed Consultation with indigenous people, the UNFCCC REDD+ safeguards (even though only implicitly) [79] (p. 26) as well as the UN-REDD SEPC [92] (p. 5) make projects that affect indigenous peoples dependent on their Free, Prior and Informed Consent, as required by the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. The 2018 World Bank ESF (and the 2012 IFC performance standards) require Free, Informed and Prior Consent at least with respect to the most relevant situations [101] (p. 107).

Even though the differences between the safeguard systems of the different financial institutions are not very large, the coexistence of several standards constitutes an organizational hurdle unnecessarily burdening national institutions tasked with coordinating REDD+ and FLR activities [37] (p. 11). Recognizing this as a problem, the two major financing institutions supporting REDD+ readiness activities, the FCPF RF and the UN-REDD Programme sought to coordinate their approaches from a very early point on. In 2012, they adopted joint Guidelines on Stakeholder Engagement in REDD+ Readiness [111] and a common Readiness Preparation Proposal Template [112]. While financial as well as implementing institutions routinely collaborate with other institutions in individual forest projects, the FCPF RF and the UN-REDD-Programme have so far been the only two institutions integrating their procedures in a permanent way.

4. Discussion

All of the financial institutions analyzed in this article have established fairly effective rules for safeguards in order to manage positive and negative externalities relevant for FLR. They thus provide a reasonably well financial infrastructure for FLR activities in developing countries. All funds promote the integration of co-benefits and consider them in their funding decisions, but countries retain great leeway in determining which co-benefits they will integrate in their programs. This is reasonable for general institutional safeguard standards, which need to fit a great variety of activities in diverse contexts. It would be desirable, however, for forest-related multilateral public funds to develop FLR-specific funding lines that contain more stringent requirements pertaining to the multiple benefits associated with the FLR concept.

The safeguard systems of all financial institutions are quite elaborate and coherent across organizations. However, areas for further improvement exist. Safeguards regarding GHG emission could become more detailed and standards for the protection of healthy ecosystems could integrate issues beyond biodiversity like land degradation and eco-system services to a greater extent. Biodiversity NGOs advocate for the inclusion of requirements regarding genetic diversity and adaptation potential of seeds used for restoration projects [113,114]. Indigenous peoples demand that their right to Free, Prior and Informed Consent is respected in all situations and that consent is clearly defined as a positive decision by affected communities’ own institutions [115], ([116], p. 51). It would be desirable that all institutions clearly rule out involuntary resettlement and include general provisions requiring countries to ensure that projects do not negatively affect local communities’ livelihoods.

Comparing institutions at the operative level of financial (and implementing) organizations with rules at the regulative level of international negotiating bodies, co-benefits as well as safeguards are more developed and inter-institutional coordination is more successful at the operative level. The UNFCCC’s Cancún safeguards for REDD+ are much less detailed and encompassing than the safeguard systems at the institutional level of the funds. While the attempt of the CBD to provide input to the UNFCCC negotiations regarding biodiversity safeguard standards for REDD+ failed to produce a binding outcome, inter-institutional coordination at the operative levels works fairly well. It involves negotiated agreements like the common standards of the FCPF and the UN-REDD Programme as well as processes of mutual adjustment. Prevailing inter-institutional dynamics at the operative level can be seen to support a race to the top: Organizations periodically update their safeguard systems to catch up with advances made by other organizations. In addition, is it usually agreed that in projects involving several funding organizations the more stringent of the safeguard provisions apply (see, e.g., ([117], p. 3), ([118], p. 12)).

Harmonization, however, takes the form of assimilation rather than resulting in a division of labor. The concept of functional differentiation would suggest that institutions take the lead in developing provisions regarding positive and negative externalities for the area of their own expertise. This has been attempted but proven unsuccessful at the regulatory level, when the CBD tried to provide biodiversity safeguards for REDD+. At the operative level, no attempts in this regard have been made. It is the World Bank that de facto sets minimum standards in all safeguard areas, including environmental issues where it has less expertise than other institutions in the field. However, while the safeguard provisions of all funds are oriented on the World Bank’s in some way, each organization nonetheless cultivates its own safeguards system. At first sight, this seems to contradict the idea of an integrated approach to FLR, suggesting that each institution has an ax to grind leading to institutional competition rather than to cooperation. Inter-institutional cooperation has proven the opposite, leading to a harmonization of safeguard rules between financial institutions supporting FLR, which do not provide problematic opportunities for forum shopping. The problem is that they have not led to a reduction of transaction costs, particularly for implementing agencies. The continuous mutual adaptation of standards requires a lot of energy from the institutions and the fact that each institution still has their own safeguard system is burdensome for recipient countries, which often need to fulfill the requirements of several institutions at the same time. It would not be desirable to reduce transaction costs by dropping some provisions from safeguard systems and thus lowering their standards. However, organizations should strive to reduce transaction costs by eliminating unnecessary duplications of standards and harmonizing application procedures (see FCPF RF/UN-REDD Programme). Ideally, all organizations would use the same safeguard system. In a functional division of labor, the standards for each issue area would be supplied by the organization with most expertise. Thus, for instance, the CBD would provide provisions for the protection of biodiversity, which would be used by all organizations. However, such a division of labor is probably too far away from prevailing practices to be easily implemented. In addition, as the CBD/UNFCCC example has shown, member countries seem to be rather reluctant to expand existing mandates. A pragmatic way to reduce transaction costs for recipient countries would be the adoption of the World Bank ESF by all organizations. De facto, all other organizations’ safeguard systems are modeled on those of the World Bank anyway. The replacement of their safeguard systems with the World Bank ESF would thus not change the substance of requirements, but it would simplify procedures for recipient countries and spare the organizations the work of periodically comparing and updating their safeguard systems. This, in turn, would require an institutionalized way of inter-organizational cooperation to jointly update and adapt safeguards, to support a race to the top and to avoid a sense of patronization. Where organizations or some of their projects really want to address safeguard issues that go beyond those of the World Bank, they could specify additional requirements in their procedures. This would make actual differences more transparent than the co-existence of several largely congruent safeguard-systems.

Acknowledgments

This article is an outcome of a research project on Raising Transformative Ambitions—Contributions of Effective Climate Instruments (Transformative Ambitionssteigerung—Der Beitrag effektiver Klimapolitikinstrumente (TABEK)), jointly carried out by Perspectives Climate Research gGmbH and the University of Freiburg (Department of Forest and Environmental Policy & Department of Political Science). The project is funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research under grant No. 01LS1621A. The research grant is part of the program on Contribution to the IPCC Special Report 1.5 degree warming (Beitrag zum IPCC Sonderbericht 1.5 Grad Erwärmung). The article processing charge was funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG) and the University of Freiburg in the funding program Open Access Publishing. We thank the two anonymous reviewers for their very constructive and helpful feedback.

Author Contributions

Astrid Carrapatoso, as first author, conceived the research question and theoretical framework and wrote the corresponding sections of this article. Angela Geck, as second author, carried out the empirical research and wrote the corresponding sections of the paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The founding sponsors had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, and in the decision to publish the results.

References

- UN General Assembly. A/RES/70/1: Seventieth Session, Agenda Items 15 and 116. Resolution Adopted by the General Assembly on 25 September 2015 [Without Reference to a Main Committee (A/70/L.1)]. 70/1. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; UN General Assembly: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD). UNEP/CBD/COP/DEC/X/2: Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity. Tenth Meeting Nagoya, Japan, 18–29 October 2010. Agenda Item 4.4: Decision Adopted by the Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity at Its Tenth Meeting X/2. The Strategic Plan for Biodiversity 2011–2020 and the Aichi Biodiversity Targets; CBD: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- UNFCCC. REDD+ Web Platform, Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation in Developing Countries. 2017. Available online: http://redd.unfccc.int/ (accessed on 29 December 2017).

- UNCCD. The LDN Target Setting Programme. 2017. Available online: http://www2.unccd.int/actions/ldn-target-setting-programme (accessed on 29 December 2017).

- GPFLR. Our Approach: The Landscape Approach. 2016. Available online: http://www.forestlandscaperestoration.org/tool/our-approach-landscape-approach (accessed on 29 December 2017).

- Hanson, C.; Buckingham, K.; DeWitt, S.; Laestadius, L. The Restoration Diagnostic: A Method for Developing Forest Landscape Restoration Strategies by Rapidly Assessing the Status of Key Success Factors; World Resources Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hanson, C. The Restoration Diagnostic: Case Example: Jutland, Denmark; World Resources Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Laestadius, L. The Restoration Diagnostic: Case Example: Southern Sweden; World Resources Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Buckingham, K.; Hanson, C. The Restoration Diagnostic: Case Example: Tijuca National Park, Brazil; World Resources Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Buckingham, K.; Hanson, C. The Restoration Diagnostic: Case Example: South Korea; World Resources Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- The Green Belt Movement. Our History. 2017. Available online: http://www.greenbeltmovement.org/who-we-are/our-history (accessed on 30 December 2017).

- Buckingham, K.; Hanson, C. The Restoration Diagnostic: Case Example: Costa Rica; World Resources Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Buckingham, K.; Hanson, C. The Restoration Diagnostic: Case Example: Shinyanga Region, Tanzania; World Resources Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Laestadius, L.; Buckingham, K.; Maginnis, S.; Saint-Laurent, C. Before Bonn and beyond: The history and future of forest landscape restoration. Unasylva 2015, 66, 11–18. [Google Scholar]

- Bonn Challenge. Home. 2017. Available online: http://www.bonnchallenge.org/ (accessed on 29 December 2017).

- UN Climate Summit. Forests. Action Statements and Action Plans; UN Climate Summit: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Pistorius, T.; Carodenuto, S.; Wathum, G. Implementing Forest Landscape Restoration in Ethiopia. Forests 2017, 8, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Dietz, T.; Carpenter, S.R.; Alberti, M.; Folke, C.; Moran, E.; Pell, A.N.; Deadman, P.; Kratz, T.; Lubchenco, J.; et al. Complexity of coupled human and natural systems. Science 2007, 317, 1513–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berkes, F.; Colding, J.; Folke, C. Navigating Social-Ecological Systems: Building Resilience for Complexity and Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Folke, C. Resilience: The emergence of a perspective for social–ecological systems analyses. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2006, 16, 253–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Mooney, H.; Hull, V.; Davis, S.J.; Gaskell, J.; Hertel, T.; Lubchenco, J.; Seto, K.C.; Gleick, P.; Kremen, C.; et al. Systems integration for global sustainability. Science 2015, 347, 1258832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Najam, A.; Papa, M.; Taiyab, N. Global Environmental Governance: A Reform Agenda; International Institute for Sustainable Development (Institut International du Développement Durable): Winnipeg, MB, Canada, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Keohane, R.O.; Victor, D.G. The Regime Complex for Climate Change. Perspect. Politics 2011, 9, 7–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raustiala, K.; Victor, D.G. The Regime Complex for Plant Genetic Resources. Int. Organ. 2004, 58, 277–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alter, K.J.; Meunier, S. The Politics of International Regime Complexity. Perspect. Politics 2009, 7, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Asselt, H.; Zelli, F. Connect the dots: Managing the fragmentation of global climate governance. Environ. Econ. Policy Stud. 2014, 16, 137–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biermann, F.; Pattberg, P.; van Asselt, H.; Zelli, F. The Fragmentation of Global Governance Architectures: A Framework for Analysis. Glob. Environ. Politics 2009, 9, 14–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Pistorius, T.; Vijge, M.J. Managing fragmentation in global environmental governance: The REDD+ Partnership as bridge organization. Int. Environ. Agreem. Politics Law Econ. 2016, 16, 355–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansourian, S. Understanding the relationship between governance and forest landscape restoration. Conserv. Soc. 2016, 14, 267–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansourian, S. Governance and forest landscape restoration: A framework to support decision-making. J. Nat. Conserv. 2017, 37, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamb, D.; Stanturf, J.; Madsen, P. What Is Forest Landscape Restoration? In Forest Landscape Restoration: Integrating Natural and Social Science; Stanturf, J., Lamb, D., Madsen, P., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2012; Volume 15, pp. 3–23. [Google Scholar]

- Van Oosten, C. Forest Landscape Restoration: Who Decides? A Governance Approach to Forest Landscape Restoration. Natureza Conservação 2013, 11, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chazdon, R.L.; Brancalion, P.H.S.; Lamb, D.; Laestadius, L.; Calmon, M.; Kumar, C. A Policy-Driven Knowledge Agenda for Global Forest and Landscape Restoration. Conserv. Lett. 2017, 10, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabogal, C.; Besacier, C.; McGuire, D. Forest and landscape restoration: Concepts, approaches and challenges for implementation. Unasylva 2015, 66, 3–10. [Google Scholar]

- Buckingham, K.; Laestadius, L. 3 Myths and Facts about Forest Landscape Restoration, WRI Blog Series New Perspectives on Restoration 3. 2014. Available online: http://www.wri.org/blog/2014/06/3-myths-and-facts-about-forest-and-landscape-restoration (accessed on 30 December 2017).

- Reinecke, S.; Pistorius, T.; Pregernig, M. UNFCCC and the REDD+ Partnership from a networked governance perspective. Environ. Sci. Policy Spec. Issue For. Clim. Policy 2014, 35, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Well, M.; Carrapatoso, A. REDD+ finance: Policy making in the context of fragmented institutions. Clim. Policy 2016, 60, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbera, E.; Schroeder, H. Governing and implementing REDD+. Environ. Sci. Policy 2011, 14, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhatre, A.; Lakhanpal, S.; Larson, A.M.; Nelson, F.; Ojha, H.; Rao, J. Social safeguards and co-benefits in REDD+: A review of the adjacent possible. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2012, 4, 654–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDermott, C.L.; Coad, L.; Helfgott, A.; Schroeder, H. Operationalizing social safeguards in REDD+: Actors, interests and ideas. Environ. Sci. Policy 2012, 21, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelsen, A.; Brockhaus, M.; Sunderlin, W.D.; Verchot, L. (Eds.) Analysing REDD+: Challenges and Choices; Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR): Bogor, Indonesia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Pistorius, T.; Reinecke, S. The interim REDD+ Partnership: Boost for biodiversity safeguards? For. Policy Econ. 2013, 36, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arhin, A.A. Safeguards and Dangerguards: A Framework for Unpacking the Black Box of Safeguards for REDD+. For. Policy Econ. 2014, 45, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tegegne, Y.T.; Ramcilovic-Suominen, S.; FOBISSIE, K.; Visseren-Hamakers, I.J.; Lindner, M.; Kanninen, M. Synergies among social safeguards in FLEGT and REDD + in Cameroon. For. Policy Econ. 2017, 75, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, O.R. Institutional Linkages in International Society: Polar Perspectives. Glob. Gov. 1996, 2, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Oberthür, S.; Gehring, T. Institutional Interaction. In Managing Institutional Complexity; Oberthür, S., Stokke, O.S., Eds.; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2011; pp. 25–58. [Google Scholar]

- Zürn, M.; Faude, B. Commentary: On Fragmentation, Differentiation, and Coordination. Glob. Environ. Politics 2013, 13, 119–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer-Lescano, A.; Teubner, G. Regime-collisions: The vain search for legal unity in the fragmentation of global law. Mich. J. Int. Law 2004, 25, 999–1046. [Google Scholar]

- Faude, B. Zur Dynamik interorganisationaler Beziehungen: Wie aus Konkurrenz Arbeitsteilung entsteht. PVS Sonderheft 2014, 49, 294–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, M.; Finnemore, M. Rules for the World: International Organizations in Global Politics; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Busch, M.L. Overlapping institutions, Forum Shopping and Dispute Settlement in International Trade. Int. Organ. 2007, 61, 735–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morse, J.C.; Keohane, R.O. Contested multilateralism. Rev. Int. Organ. 2014, 9, 385–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drezner, D.W. Two challenges to institutionalism. In Can the World Be Governed? Possibilities for Effective Multilateralism; Alexandroff, A., Ed.; Wilfrid Laurier University Press; Center for International Governance Innovation (CIGI): Waterloo, ON, USA, 2008; pp. 139–159. [Google Scholar]

- Drezner, D.W. The Power and Peril of International Regime Complexity. Perspect. Politics 2009, 7, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benvenisti, E.; Downs, G.W. The empire’s new clothes: Political economy and the fragmentation of international law. Stanf. Law Rev. 2007, 60, 595–632. [Google Scholar]

- Orsini, A.; Morin, J.-F.; Young, O.R. Regime Complexes: A Buzz, a Boom, or a Boost for Global Governance? Glob. Gov. 2013, 19, 27–39. [Google Scholar]

- Gehring, T.; Faude, B. A theory of emerging order within institutional complexes: How competition among regulatory international institutions leads to institutional adaptation and division of labor. Rev. Int. Organ. 2014, 9, 471–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Underdal, A.; Young, O.R. Research strategies for the future. In Regime Consequences: Methodological Challenges and Research Strategies; Underdal, A., Young, O.R., Eds.; Kluwer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2004; pp. 361–380. [Google Scholar]

- Abbott, K.W.; Green, J.F.; Keohane, R.O. Organizational Ecology and Organizational Strategies in World Politics; Harvard Kennedy School: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hanrieder, T. Die Weltgesundheitsorganisation unter Wettbewerbsdruck. Auswirkungen der Vermarktlichung globaler Gesundheitspolitik. In Die Organisierte Welt. Internationale Beziehungen und Organisationsforschung; Dingwerth, K., Kerwer, D., Nölke, A., Eds.; Nomos: Baden-Baden, Germany, 2009; pp. 165–188. [Google Scholar]

- Holzscheiter, A. Interorganisationale Harmonisierung als sine qua non für die Effektivität von Global Governance? Eine soziologisch-institutionalistische Analyse interorganisationaler Strukturen in der globalen Gesundheitspolitik. PVS Sonderheft 2014, 49, 322–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lee, D.; Pistorius, T. The Impacts of International REDD+ Finance. 2015. Available online: http://www.climateandlandusealliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Impacts_of_International_REDD_Finance_Report_FINAL.pdf (accessed on 11 February 2018).

- Falconer, A.; Glenday, S. Taking Stock of International Contributions to Low Carbon, Climate Resilient Land Use in Indonesia; A CPI Working Paper; Climate Policy Initiative: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Daviet, F.; Larsen, G.; Lee, D.; Roe, S.; O’Sullivan, R.; Streck, C. Safeguards for REDD+ from a Donor Perspective. 2013. Available online: http://www.fcmcglobal.org/documents/Climate_Focus_Safeguards_Report.pdf (accessed on 11 February 2018).

- Severino, J.-M.; Ray, O. The End of ODA (II). The Birth of Hypercollective Action; Center for Global Development: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Climate Focus. Progress on the New York Declaration on Forests: Finance for Forests—Goals 8 and 9 Assessment Report. Prepared by Climate Focus in Cooperation with the New York Declaration on Forest Assessment Partners with Support from the Climate and Land Use Alliance; Climate Focus: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- FAO; Global Mechanism of the UNCCD. Sustainable Financing for Forest and Landscape Restoration: Opportunities, Challenges and the Way Forward: Discussion Paper; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Global Environment Facility (GEF). GEF-6 Programming Directions: Extract from GEF Assembly Document GEF/A.5/07/Rev.01; GEF: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Green Climate Fund (GCF). GCF/B.18/06: Meeting of the Board, 30 September–2 October 2017, Cairo, Arab Republic of Egypt, Provisional Agenda Item 14(b): Request for Proposals for the Pilot Programme for REDDplus Results-Based Payments; GCF: Songdo, Korea, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Green Climate Fund (GCF). GCF/B.17/16: Meeting of the Board, 5–6 July 2017, Songdo, Incheon, Republic of Korea, Provisional Agenda Item 19(b): Green Climate Fund Support for the Early Phases of REDD-Plus; GCF: Songdo, Korea, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- UNEP. Press Release: New Collaboration Launched to Restore the World’s Forests. 2014. Available online: https://www.unenvironment.org/news-and-stories/press-release/new-collaboration-launched-restore-worlds-forests (accessed on 19 November 2017).

- BioCF ISFL. The ISFL Vision; BioCF ISFL: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- FCPF. About. 2017. Available online: https://www.forestcarbonpartnership.org/about-fcpf-0 (accessed on 20 November 2017).

- Climate Investment Funds (CIF). CIF/DMFIP.2/2: Second Design Meeting on the Forest Investment Program, Washington, D.C, March 5–6, 2009: Forest Investment Program Design Document (Prepared by the Forest Investment Program Working Group); CIF: Washington, DC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Forest Investment Program (FIP). Forests, Development, and Climate: Achieving a Triple Win; FIP: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Sustaining Forests. A Development Strategy; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. World Bank Group Forest Action Plan FY16–20; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). FCCC/CP/2015/10/Add.1: Report of the Conference of the Parties on Its Twenty-First Session, Held in Paris from 30 November to 13 December 2015, Addendum, Part Two: Action Taken by the Conference of the Parties at Its Twenty-First Session. Decisions Adopted by the Conference of the Parties. 1/CP.21 Adoption of the Paris Agreement; UNFCCC: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). FCCC/CP/2010/7/Add.1: Conference of the Parties: Report of the Conference of the Parties on Its Sixteenth Session, Held in Cancun from 29 November to 10 December 2010, Addendum Part Two: Action Taken by the Conference of the Parties at Its Sixteenth Session; UNFCCC: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD). ICCD/COP(13)/L.18: Conference of the Parties, Thirteenth Session, Ordos, China, 6–16 September 2017, Agenda Item 2 (b): 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development: Implications for the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification. The Future Strategic Framework of the Convention; UNCCD: Bonn, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- GEF STAP. GEF/R7/Inf.10: Second Meeting for the Seventh Replenishment of the GEF Trust Fund, October 3–5, 2017, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: GEF-7 Replenishment. Draft STAP Working Paper: Why the Scientific Community Is Moving towards Integration of Environmental, Social, and Economic Issues to Solve Complicated Problems. (Prepared by the Scientific and Technical Advisory Panel); GEF STAP: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Interview with Representative of a GEF Implementing Agency at the UNFCCC COP23; UNFCCC: Bonn, Germany, 2017.

- Interview with GEF Representative at the Global Landscape Forum; UNFCCC: Bonn, Germany, 2017.

- Global Environment Facility (GEF). GEF/R.7/02: First Meeting for the Seventh Replenishment of the GEF Trust Fund, March 28–30, 2017, Paris: GEF-7 Programming Directions and Policy Agenda (Prepared by the GEF Secretariat); GEF: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Global Environment Facility (GEF). GEF/R.7/06 Draft: Second Meeting for the Seventh Replenishment of the GEF Trust Fund: GEF-7 Replenishment. Programming Directions and Policy Agenda (Prepared by the Secretariat); GEF: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Green Climate Fund (GCF). GCF/B.07/11: Decisions of the Board—Seventh Meeting of the Board, 18–21 May 2014; GCF: Songdo, Korea, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Green Climate Fund (GCF). GCF/B.09/23, Annex 3: Initial Investment Framework: Activity-Specific Sub-Criteria and Indicative Assessment Factors; GCF: Songdo, Korea, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Green Climate Fund (GCF). GCF/B.17/13: Meeting of the Board, 5–6 July 2017, Songdo, Incheon, Republic of Korea, Provisional Agenda Item 19(a): Pilot Programme for REDD+ Results-Based Payments; GCF: Songdo, Korea, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). FCCC/CP/2013/10/Add.1: Report of the Conference of the Parties on Its Nineteenth Session, Held in Warsaw from 11 to 23 November 2013, Addendum, Part Two: Action Taken by the Conference of the Parties at Its Nineteenth Session; UNFCCC: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). FCCC/CP/2015/10/Add.3: Report of the Conference of the Parties on Its Twenty-First Session, Held in Paris from 30 November to 11 December 2015. Addendum. Part Two: Action Taken by the Conference of the Parties at Its Twenty-First Session; UNFCCC: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- UN-REDD Programme. UNREDD/PB7/2011/I/1: UN-REDD Programme Strategic Framework 2016-20 (Revised Draft—7 Mas 2015) UN-REDD Programme Fourteenth Policy Board Meeting 20–22 May 2015, Washington, DC, USA; UN-REDD Programme: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- UN-REDD Programme. UNREDD/PB8/2012/V/1: UN-REDD Programme Social and Environmental Principles and Criteria. UN-REDD Programme Eights Policy Board Meeting 25–26 March 2012. Asunción, Paraguay; UN-REDD Programme: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Forest Carbon Partnership Facility (FCPF). Carbon Fund Methodological Framework; FCPF: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- BioCF ISFL. ISFL Emission Reductions (ER) Program Requirements: Version 1; BioCF ISFL: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- BioCF ISFL. Monitoring, Evaluation, and Learning (MEL) Framework; BioCF ISFL: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Climate Investment Funds (CIF). Results Monitoring and Reporting in the FIP; CIF: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- CBD Secretariat. Connecting Biodiversity and Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation: Report of the Second Ad Hoc Technical Expert Group on Biodiversity and Climate Change; CBD Secretariat: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Pistorius, T.; Schmitt, C.B. (Eds.) The Protection of Forests under Global Biodiversity and Climate Policies: Policy Options and Case Studies on Greening REDD+; BfN Federal Agency for Nature Conservation: Bonn, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD). UNEP/CBD/SBSTTA/16/8: Subsidiary Body on Scientific, Technical and Technological Advice: Sixteenth Meeting, Montreal, 30 April–5 May 2012. Item 7.1 of the Provisional Agenda: Advice on the Application of Relevant REDD+ Safeguards for Biodiversity, and on Possible Indicators and Potential Mechanisms to Assess Impacts of REDD+ Measures on Biodiversity. Note by the Executive Secretary; CBD: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD). UNEP/CBD/COP/11/35: Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity. Eleventh Meeting, Hyderabad, India, 8–19 October 2012. Report on the Eleventh Meeting of the Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity; CBD: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Environmental and Social Framework: Setting Environmental and Social Standards for Investment Project Financing; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- International Finance Corporation (IFC). Performance Standards on Environmental and Social Sustainability; IFC: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Global Environment Facility (GEF). Policy: SD/PL/03: Agency Minimum Standards on Environmental and Social Safeguards; Last Updated 19.02.2015; GEF: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Operational Manual—OP 4.00—Piloting the Use of Borrower Systems to Address Environmental and Social Safeguard Issues in Bank-Supported Projects; Revised April 2013; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- FCPF Carbon Fund. FMT Note CF-2013-3: World Bank Safeguard Policies and the UNFCCC REDD+ Safeguards; FCPF Carbon Fund: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Climate Investment Funds (CIF). FIP: Investment Criteria and Financing Modalities; CIF: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Operational Manual—OP 4.36—Forests; Revised April 2013; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Operational Manual—OP 4.04—Natural Habitats; Revised April 2013; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Operational Manual—OP 4.12—Involuntary Resettlement; Revised April 2013; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Operational Manual—OP 4.10—Indigenous Peoples; Revised April 2013; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- FCPF; UN-REDD Programme. Guidelines on Stakeholder Engagement in REDD+ Readiness: With a Focus on the Participation of Indigenous Peoples and Other Forest-Dependent Communities; FCPF; UN-REDD Programme: Washington, DC, USA; Geneva, Switzerland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- FCPF; UN-REDD Programme. Readiness Preparation Proposal (R-PP) Template; Version 6 Working Draft, for Country Use; FCPF; UN-REDD Programme: Washington, DC, USA; Geneva, Switzerland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Interview with NGO Representative at the Global Landscape Forum; UNFCCC: Bonn, Germany, 2017.

- Bioversity International. Safeguarding Investments in Forest Ecosystem Restoration: Policy Brief; Bioversity International: Rome, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Interview with Representative of Indigenous Peoples Organization at the Global Landscape Forum; UNFCCC: Bonn, Germany, 2017.

- Tebtebba Foundation. Indigenous People and the Green Climate Fund; Tebtebba Foundation: Baguio City, Philippines, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- FCPF Readiness Fund. Common Approach to Environmental and Social Safeguards for Multiple Delivery Partners: Revised Version; FCPF Readiness Fund: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Green Climate Fund (GCF). GCF/2017/Inf.02: Meeting of the Board, 30 September–2 October 2017, Cairo, Arab Republic of Egypt: Environmental and Social Management System; GCF: Songdo, Korea, 2017. [Google Scholar]

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).