Environmental Practices. Motivations and Their Influence on the Level of Implementation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Contextualization of the Topic and Working Hypotheses

2.1. Environmental Management in the Health Resort

2.2. Hypothesis Testing: Motivations

3. Methodology

3.1. Universe Study, Questionnaire and Measurement

3.2. Analysis of Data

4. Results

4.1. Environmental Diagnosis of Health Resorts

4.1.1. Reasons for Implementing Environmental Practices

4.1.2. Organization vs. Environmental Practices

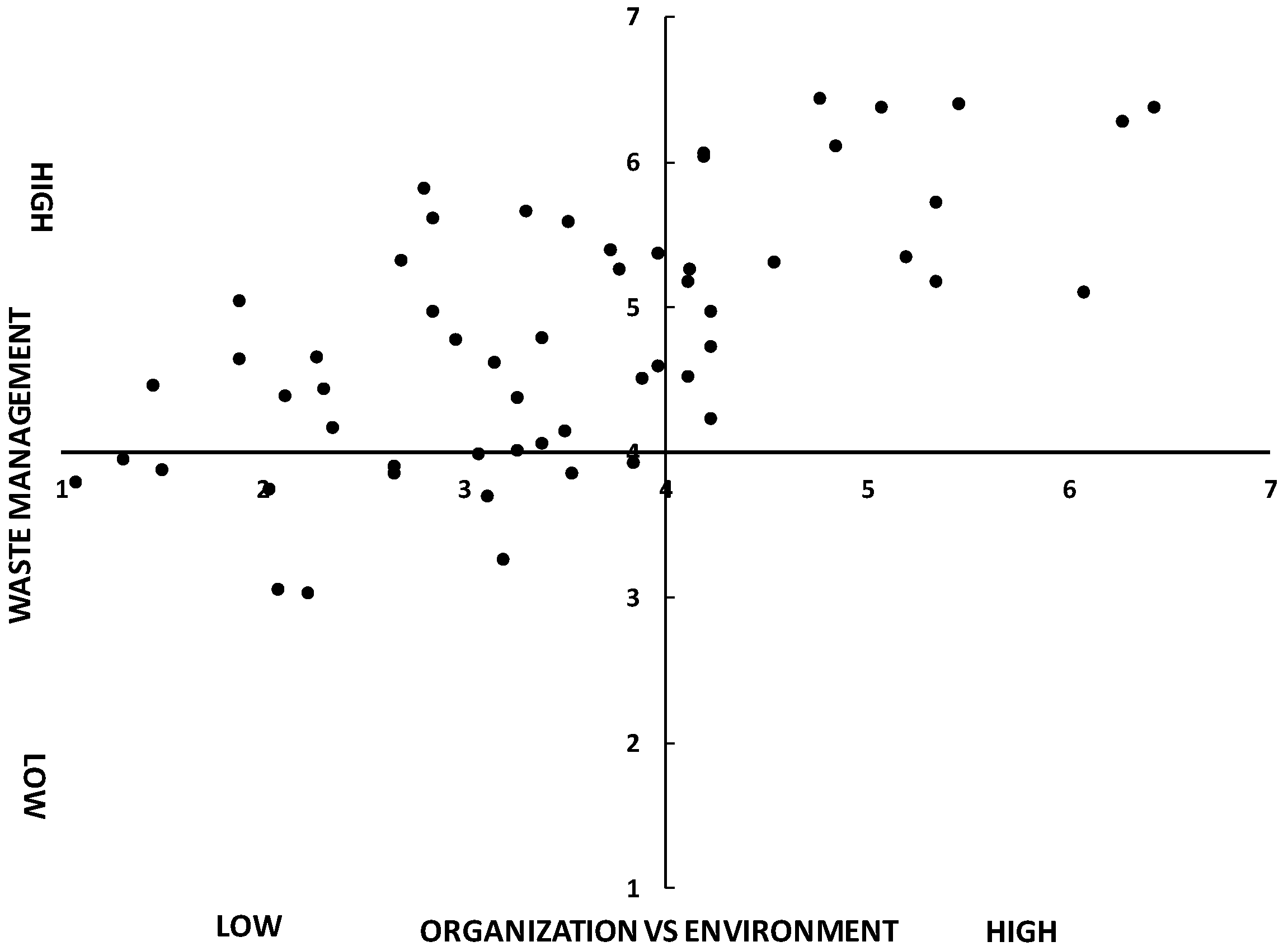

4.1.3. The Organization vs. Environment

4.1.4. Resources Management

4.2. Testing the Working Hypotheses

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Items | Mean | S.D. | (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Organization vs. Environmental Practices | |||

| We have clearly defined an environmental policy, with realistic objectives, clearly defined and measurable | 4.57 | 1.64 | 65.34 |

| We have an environment manager, with clearly defined tasks | 3.72 | 1.66 | 53.16 |

| The staff is informed of the environmental policy and objectives | 4.48 | 1.75 | 63.93 |

| The staff is trained and aware about environmental management | 4.52 | 1.44 | 64.64 |

| The staff is aware-involved in environmental management | 4.55 | 1.52 | 65.00 |

| Training schemes on environmental issues are carried out | 3.39 | 1.86 | 48.48 |

| We encourage our staff to contribute their own ideas to improve in environmental issues and the best ones are developed | 3.98 | 1.66 | 56.91 |

| We have an incentive scheme to motivate staff to provide environmental ideas and the best ones are developed | 2.30 | 1.39 | 32.79 |

| The results obtained in environmental issues are evaluated and compared with those planned, with the aim of achieving improvements | 3.21 | 1.88 | 45.90 |

| With the results obtained in environmental issues the objectives are achieved | 3.36 | 1.76 | 48.01 |

| Workers and customers are informed of the results obtained | 3.02 | 1.74 | 43.10 |

| Total | 3.74 | --- | 53.39 |

| The organization vs the environment (customers, suppliers and society) | |||

| Customers | |||

| We have a defined environmental commitment that is public (on the web, at reception ... etc.) | 3.23 | 2.19 | 46.14 |

| The results obtained in environmental issues are available to clients in a visible place (on the web, in reception ...) | 2.57 | 1.66 | 36.77 |

| Adequate means are available to clients (forms, suggestion boxes, etc.) to express their opinions and suggestions on environmental issues and the best ones are developed | 3.98 | 2.21 | 59.91 |

| We contribute to the environmental awareness of our customers by informing them of our policy and requirements, as well as providing guides (upcoming ecological itineraries ...), brochures (water, energy ... etc. saving) or other means | 3.93 | 1.99 | 56.21 |

| Customers are interested in our environmental policy | 2.75 | 1.41 | 39.34 |

| Total | 3.29 | --- | 47.07 |

| Suppliers | |||

| Our suppliers are informed of our interest in the environment, by informing them of our environmental policy and its requirements (environmentally-friendly products) | 3.85 | 1.97 | 55.04 |

| We are preferably looking for recyclable products or recycled material and in general, those with characteristics that minimize environmental impact | 4.43 | 1.70 | 63.23 |

| We are willing to pay more for environmentally-friendly products | 3.89 | 1.53 | 55.50 |

| We inform our suppliers of the results obtained | 2.46 | 1.58 | 35.13 |

| Suppliers show interest in our environmental policy | 2.45 | 1.54 | 35.00 |

| Total | 3.41 | --- | 48.79 |

| Society | |||

| The local society is aware of our interest in the environment | 3.13 | 1.77 | 44.73 |

| We participate in local initiatives (of associations, diverse institutions, etc.) that are carried out in favour of the environment | 3.39 | 1.86 | 48.48 |

| We carry out actions that contribute to the ecological and vegetal restoration of our natural environment | 4.56 | 1.74 | 65.11 |

| We inform the local society of the results obtained | 2.87 | 1.62 | 40.98 |

| The local society shows interest in our environmental policy | 2.67 | 1.42 | 38.17 |

| Total | 3.32 | --- | 47.50 |

| Resources | |||

| Water saving | |||

| We know our water consumption | 6.41 | 0.94 | 91.57 |

| We have set measurable targets to reduce our water consumption | 5.67 | 1.36 | 81.03 |

| We know and control consumption by areas or sections (thermal area, rooms, kitchen, etc.) to establish savings measures | 5.08 | 1.77 | 72.60 |

| We have continuous measuring and network analysis equipment to obtain information and determine the required savings and adjustments | 4.75 | 1.78 | 67.92 |

| We have a leak detection system for immediate repair | 3.74 | 1.94 | 53.40 |

| We have installed low-consumption taps, showers and cisterns (with eco function) suitable for saving water | 5.10 | 1.69 | 72.83 |

| We offer our clients the necessary information for the proper use of water and saving in its consumption | 5.18 | 1.54 | 74.00 |

| The water circuit allows closing the water supply in unoccupied areas | 4.97 | 1.92 | 70.96 |

| Rainwater is collected for watering gardens | 3.00 | 2.23 | 42.86 |

| We have native plants in our gardens, prepared to survive with natural water resources | 4.84 | 1.93 | 69.09 |

| The gardens are equipped with irrigation systems that save water consumption (with eco function) | 4.30 | 2.09 | 61.36 |

| Watering gardens is done at hours when there is less sunlight to reduce loss of water due to its evaporation | 5.48 | 1.62 | 78.22 |

| Workers and clients are informed of the consumption obtained | 2.62 | 1.59 | 37.47 |

| The staff has precise knowledge and instructions aimed at promoting water consumption as efficiently as possible | 5.13 | 1.74 | 73.30 |

| Total | 4.73 | --- | 67.61 |

| Energy saving | |||

| We know our energy consumption | 6.48 | 0.84 | 92.51 |

| We have established measurable goals to reduce our energy consumption | 5.85 | 1.10 | 83.61 |

| We know and control consumption by areas or sections to establish savings measures (thermal area, rooms, kitchen, etc.) | 5.13 | 1.60 | 73.30 |

| We have energy control systems (timers, thermostats, presence detectors, etc.) | 5.66 | 1.38 | 80.80 |

| Energy audits of the facilities are performed | 4.70 | 1.72 | 67.21 |

| The heated areas are organized, thus avoiding useless energy expenditures | 5.25 | 1.26 | 74.94 |

| We perform adequate maintenance of boilers, pipes and radiators (cleaning and regular purging) and air conditioning facilities (cleaning filters and changing them) | 6.13 | 0.99 | 87.59 |

| The health resort establishment has good ventilation and thermal insulation to avoid resorting as little as possible to air conditioning and avoid condensation | 5.52 | 1.35 | 78.92 |

| We have revolving doors to avoid the loss of heat or cold in each case, windows with thermal bridge breaking and double glass | 4.00 | 1.86 | 57.14 |

| We have installed solar panels, and we intend to progressively increase the generation and use of this type of energy (clean) | 3.49 | 2.38 | 49.88 |

| When replacing equipment, we always opt for the most energy efficient | 5.66 | 1.46 | 80.80 |

| The lighting of the establishment is calculated and aimed at reducing energy consumption (energy-saving bulbs or low consumption LEDs, etc.) | 5.90 | 1.37 | 84.31 |

| We have installed photovoltaic sensors in outdoor lighting | 4.05 | 2.19 | 57.85 |

| Workers and clients are informed about the consumption obtained | 2.43 | 1.45 | 34.66 |

| The staff has precise knowledge and instructions aimed at promoting energy consumption that is as efficient as possible | 5.07 | 1.52 | 72.37 |

| Total | 5.02 | --- | 71.73 |

| Pollution and waste management | |||

| We know and control the quantities of waste generated and in their different categories: containers and packaging, organic waste, special waste (cooking oils and grease, toner ...) and hazardous waste (batteries, fluorescents, light bulbs ...) | 5.21 | 1.70 | 74.47 |

| We have set measurable targets to reduce waste generation | 4.15 | 2.00 | 59.25 |

| We have a record of the hazardous waste we generate | 4.93 | 2.05 | 70.49 |

| This hazardous waste is stored in a safe place until its collection to avoid its manipulation | 5.54 | 1.78 | 79.16 |

| Special and hazardous waste is treated in a special way, being withdrawn by authorized companies specialized in its treatment | 5.77 | 1.59 | 82.44 |

| We classify the containers and packaging separating their different types: glass, plastic, metal and paper-cardboard for recycling | 5.56 | 1.54 | 79.39 |

| In order to facilitate the collection of waste and recycling by staff and/or customers, rubbish containers are of different colours in accordance with the regulations | 5.31 | 1.80 | 75.88 |

| We have posters in visible places to remind staff and customers of the need to separate waste for recycling | 4.44 | 2.18 | 63.47 |

| Workers and clients are informed about the results obtained | 2.67 | 1.68 | 38.17 |

| The staff has precise knowledge and instructions aimed at reducing the generation of waste | 5.20 | 1.79 | 74.24 |

| Total | 4.88 | --- | 69.70 |

| Noise | |||

| To reduce noise, the doors and windows of the facilities are made of materials suitable for this purpose | 4.92 | 1.63 | 70.26 |

| In areas with greater noise (dining room, meeting room ...), the walls are covered with materials that absorb the noise | 4.25 | 1.60 | 60.66 |

| The floors are covered with suitable materials to avoid the noise that occurs with people‘s movements | 4.31 | 1.78 | 61.59 |

| When choosing machinery for our facilities, we choose the ones that give off the least possible noise (boilers, purifiers, etc.) | 4.98 | 1.73 | 71.19 |

| We have installed volume limiters in Televisions, etc. | 3.57 | 2.19 | 51.05 |

| The machinery of greater acoustic impact is installed in suitable areas reducing its acoustic impact. | 5.16 | 1.70 | 73.77 |

| Total | 4.53 | --- | 64.75 |

References

- WTTC. Economic Impact Annual Update Summary. World Travel & Tourism Council, 2016. Available online: http://sp.wttc.org/-/media/files/reports/economic-impact-research/2016-documents/economic-impact-summary-2016_a4-web.pdf (accessed on 22 August 2017).

- WTTC. Travel and Tourism. Economic Impact 2016 Spain. World Travel & Tourism Council, 2013. Available online: http://sp.wttc.org/-/media/files/reports/economic-impact-research/countries-2016/spain2016.pdf (accessed on 14 September 2017).

- Crosby, A.; Moreda, A. Elementos Básicos Para un Turismo Sostenible en Las Áreas Naturales; Centro Europeo de Formación Ambiental y Turística (CEFAT): Madrid, Spain, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- WTO. World Tourism Organization. Available online: http://sdt.unwto.org/es/content/definicion (accessed on 28 August 2016).

- Word Tourism Organization. Word Tourism Organization Network. Available online: http://www2.unwto.org/es (accessed on 28 August 2017).

- Fullana, P.; Ayuso, S. Turisme Sostenible, Rubes ed.; Departament de Medi Ambient: Barcelona, Spain, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Saizarbitoria, I.H.; Landín, G.A.; Azorín, J.F.M. EMAS Versus ISO 14001: Un Análisis de su Incidencia en la UE y España; Boletín Económico de ICE: Madrid, Spain, 2008; pp. 49–64. [Google Scholar]

- Conde, J.; Pascual, S.; Sánchez, I. La gestión ambiental en la empresa. In Empresa y Medio Ambiente, Hacia la Gestión Sostenible; Conde, J., Ed.; Nivola: Madrid, Spain, 2003; pp. 43–67. [Google Scholar]

- Melnyk, S.A.; Sroufe, R.P.; Calantone, R.L. Assessing the effectiveness of US voluntary environmental programmes: An empirical study. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2002, 40, 1853–1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J. A comparative study on motivation for and experience with ISO 9000 and ISO 14000 certification among Far Eastern countries. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2003, 103, 564–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zutshi, A.; Sohal, A. Environmental management system adoption by Australasian organisations: Part 1: Reasons, benefits and impediments. Technovation 2004, 24, 335–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, S.X.; Tam, C.M.; Tam, V.W.; Deng, Z.M. Towards implementation of ISO 14001 environmental management systems in selected industries in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2005, 13, 645–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poksinska, B.; Jörn Dahlgaard, J.; Eklund, J.A. Implementing ISO 14000 in Sweden: Motives, benefits and comparisons with ISO 9000. Int. J. Qual. Reliab. Manag. 2003, 20, 585–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavronski, I.; Ferrer, G.; Paiva, E.L. ISO 14001 certification in Brazil: Motivations and benefits. J. Clean. Prod. 2008, 16, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Link, S.; Naveh, E. Standardization and discretion: Does the environmental standard ISO 14001 lead to performance benefits? IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2006, 53, 508–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, K.S. Factors influencing ISO 14000 implementation in printed circuit board manufacturing industry in Hong Kong. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 1999, 42, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, A.A.; Lenox, M.J.; Terlaak, A. The strategic use of decentralized institutions: Exploring certification with the ISO 14001 management standard. Acad. Manag. J. 2005, 48, 1091–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potoski, M.; Prakash, A. Covenants with weak swords: ISO 14001 and facilities’ environmental performance. J. Policy Anal. Manag. 2005, 24, 745–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas Sánchez, A.; Vaca Acosta, R.M.; García De Soto Camacho, E. Guía de Buenas Prácticas Ambientales. Sector Turismo (Hoteles y Campos de Golf) 2003. Fundación Biodiversidad. Available online: http://www.uhu.es/alfonso_vargas/archivos/GUIA%20BUENAS%20PRACTICAS%20AMBIENTALES %20TURISMO%20definitiva-Huelva-2003.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2017).

- López López, A. El medio ambiente y las nuevas tendencias turísticas: Referencia a la región de Extremadura. Obs. Medioambient. 2001, 4, 205–251. [Google Scholar]

- Casadesus, M.; Heras, I.; Merino, J. Calidad Práctica. Una Guía Para No Perderse en el Mundo de la Calidad; Prentice Hall: Madrid, Spain, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Greeno, J.L.; Hedstrom, G.S.; Diberto, M. Enviromental Auditing-Fundamentals and Techniques; John Wiley and Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Yiridoe, E.K.; Clark, J.S.; Marett, G.E.; Gordon, R.; Duinker, P. ISO 14001 EMS standard registration decisions among Canadian organizations. Agribusiness 2003, 19, 439–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montabon, F.; Melnyk, S.A.; Sroufe, R.; Calantone, R.J. ISO 14000: Assessing its perceived impact on corporate performance. J. Supply Chain Manag. 2000, 36, 4–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolln, K.; Prakash, A. EMS-based environmental regimes as club goods: Examining variations in firm-level adoption of ISO 14001 and EMAS in UK, US and Germany. Policy Sci. 2002, 35, 43–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, P.; Bogner, W.C. Deciding on ISO 14001: Economics, institutions, and context. Long Range Plan. 2002, 35, 269–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rondinelli, D.; Vastag, G. Panacea, common sense, or just a label?: The value of ISO 14001 environmental management systems. Eur. Manag. J. 2000, 18, 499–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariotti, F.; Kadasah, N.; Abdulghaffar, N. Motivations and barriers affecting the implementation of ISO 14001 in Saudi Arabia: An empirical investigation. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excell. 2014, 25, 1352–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boiral, O.; Henri, J.F. Modelling the impact of ISO 14001 on environmental performance: A comparative approach. J. Environ. Manag. 2012, 99, 84–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bansal, P.; Roth, K. Why companies go green: A model of ecological responsiveness. Acad. Manag. J. 2000, 43, 717–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schylander, E.; Martinuzzi, A. ISO 14001—Experiences, effects and future challenges: A national study in Austria. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2007, 16, 133–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Durana, D.D.J.G. Regulación Empresarial Voluntaria y Medio Ambiente: Análisis de la Adopción de ISO 14001 en Las Organizaciones de la CAPV. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad del País Vasco, Leioa, Spain, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Generalitat Valenciana. Las Buenas Prácticas Ambientales en la Hostelería y Ocio. Conselleria De Medi Ambient, Generalitat Valenciana. 2003. Available online: http://www.fundacionglobalnature.org/proyectos/tuismo_y_ma/Manual%20BP%20Hosteler%EDa%20y%20ocio.pdf (accessed on 17 June 2017).

- Ministerio de Trabajo y Asuntos Sociales (MTAS). Manual de Buenas Prácticas Ambientales en Las Familias Profesionales: Turismo y Hostelería. España: ANALITER. 2017. Available online: http://www.magrama.gob.es/es/calidad-y-evaluacion-ambiental/temas/red-de-autoridades-ambientales-raa-/sensibilizacion-medioambiental/manuales-de-buenas-practicas/ (accessed on 17 June 2017).

- Nunnally, J.C. Pychometric Theory; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Bagozzi, R.B.; Baumgartner, H. The evaluation of structural equation models and hypothesis testing. In Principles of Marketing Research; Richard, P.B., Ed.; Blackwell Publishers: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1994; pp. 386–422. [Google Scholar]

- Nurosis, M.J. SPSS. Statistical Data Análisis; SPSS Inc.: Chicago, IL, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Grande, I.; Abascal, E. Fundamentos y Técnicas de Investigación Comercial, 5th ed.; ESIC Editorial: Madrid, Spain, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Darnall, N.; Gallagher, D.R.; Andrews, R.N. ISO 14001: Greening management systems. In Greener Manufacturing and Operations; Greenleaf Publishing: Oxon, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Hillary, R. Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises and the Environment: Business Imperatives; Greenleaf Publishing: Oxon, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Kitazawa, S.; Sarkis, J. The relationship between ISO 14001 and continuous source reduction programs. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2000, 20, 225–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeBoer, J.; Panwar, R.; Rivera, J. Toward A Place-Based Understanding of Business Sustainability: The Role of Green Competitors and Green Locales in Firms’ Voluntary Environmental Engagement. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2017, 26, 940–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fryxell, G.E.; Chung, S.S.; Lo, C.W. Does the selection of ISO 14001 registrars matter? Registrar reputation and environmental policy statements in China. J. Environ. Manag. 2004, 71, 45–57. [Google Scholar]

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Internal Motivation | 1 | ||||

| External Motivation | 0.538 * | 1 | |||

| Organization vs Practices | 0.373 ** | 0.420 * | 1 | ||

| Organization vs Environmental | 0.445 * | 0.442 * | 0.776 * | 1 | |

| Resources | 0.492 * | 0.345 ** | 0.554 * | 0.712 ** | 1 |

| Dependent Variables | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organization | Organization vs Environmental | Resource Management | Environmental Practices | |

| Independent variables | ||||

| Internal motivations | 0.308 * | 0.291 * | 0.113 | 0.329 * |

| External Motivations | 0.207 | 0.286 * | 0.432 * | 0.287 * |

| Model Information | ||||

| R2 | 0.206 | 0.256 | 0.252 | 0.287 |

| F for Regression | 7.545 ** | 9.976 ** | 9.9746 ** | 11.685 ** |

| Durbin Watson | 2.176 | 2.127 | 1.680 | 1.966 |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Del Río-Rama, M.D.l.C.; Álvarez-García, J.; Oliveira, C. Environmental Practices. Motivations and Their Influence on the Level of Implementation. Sustainability 2018, 10, 713. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10030713

Del Río-Rama MDlC, Álvarez-García J, Oliveira C. Environmental Practices. Motivations and Their Influence on the Level of Implementation. Sustainability. 2018; 10(3):713. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10030713

Chicago/Turabian StyleDel Río-Rama, María De la Cruz, José Álvarez-García, and Cristiana Oliveira. 2018. "Environmental Practices. Motivations and Their Influence on the Level of Implementation" Sustainability 10, no. 3: 713. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10030713

APA StyleDel Río-Rama, M. D. l. C., Álvarez-García, J., & Oliveira, C. (2018). Environmental Practices. Motivations and Their Influence on the Level of Implementation. Sustainability, 10(3), 713. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10030713