Abstract

Policymakers worldwide are promoting the use of bio-based products as part of sustainable development. Nonetheless, there are concerns that the bio-based economy may undermine the sustainability of the transition, e.g., from the overexploitation of biomass resources and indirect impacts of land use. Adequate assessment methods with a broad systems perspective are thus required in order to ensure a transition to a sustainable, bio-based economy. We review the scientifically published life cycle studies of bio-based products in order to investigate the extent to which they include important sustainability indicators. To define which indicators are important, we refer to established frameworks for sustainability assessment, and include an Open Space workshop with academics and industrial experts. The results suggest that there is a discrepancy between the indicators that we found to be important, and the indicators that are frequently included in the studies. This indicates a need for the development and dissemination of improved methods in order to model several important environmental impacts, such as: water depletion, indirect land use change, and impacts on ecosystem quality and biological diversity. The small number of published social life cycle assessments (SLCAs) and life cycle sustainability assessments (LCSAs) indicate that these are still immature tools; as such, there is a need for improved methods and more case studies.

Keywords:

sustainability; life cycle assessment; SLCA; social; economic; LCC; LCSA; bio-based; bioeconomy 1. Introduction

Policymakers in many countries have developed goals and strategies for the development of bio-economies as a means to reach sustainability goals, secure energy supplies, and develop competitive, innovative products [1,2,3,4]. Sweden, in particular, with vast resources of biomass, has created increased optimism on the emergence of a bio-based economy [5]. In recent years, the use of renewable energy has dramatically increased compared with other European member states, and the share of renewables in the Swedish transport sector is dominated by biofuels [6]. In addition, the use of bio-based materials in other sectors has also continually increased to meet demands [5].

Nonetheless, while several policy documents have promoted the bio-based economy in Sweden on many positive premises [3], there are also concerns that the expectations created for the bio-based economy may undermine the sustainability of the transition [7]. Examples include the overexploitation of biomass resources, and indirect impacts of land use [8,9].

In order to ensure a sustainable transition to a bio-based economy, it is important that appropriate assessment methods exist and are applied for assessing the advantages and disadvantages of available options from a sustainability perspective. To reduce the risk of sub-optimization and burden-shifting, methods should have a broad systems perspective. Addressing such concerns, life cycle-based tools have been developed, including tools to review environmental impacts through life cycle assessments (LCA), economic indicators through life cycle costing (LCC), and social indicators throughout the life cycle using social life cycle assessments (SLCA).

The past decade saw the development of different frameworks for life cycle sustainability assessments (LCSA) in order to combine the environmental, economic, and social perspectives; e.g., Klöpffer [10] and Guinée et al. [11]. While the importance of using the life cycle perspective is not contested, the way in which such an assessment can and should be conducted is still debated, as LCSA struggles with applicability challenges [12]. Examples of challenges include identifying the scope of the economic, social and environmental impacts that need to be assessed, understanding and managing the complex relationship between these impacts, selecting indicators for the impacts, and finding input data [13,14]. Therefore, it is important to understand how LCSA is being used, as well as its development and potential for improvement. In this study, we focus on the choice of indicators in life cycle studies relevant to a bio-based Swedish economy.

There is a limited number of reviews specific to the indicators, their selection, etc. in the literature for LCSA. However, Kühnen and Hahn [15] recently presented a systematic review of indicators in the global scientific SLCA literature across all of the sectors, finding that the social aspects most commonly accounted for relate to workers’ health and safety. A review of environmental life cycle assessments on biofuels in Sweden found that these studies typically include a small number of environmental indicators; see Lazarevic and Martin [16]. Several previous reviews with a broad scope have criticized such limitations, and recommend including a wider range of indicators [17,18,19] as the different environmental impacts do not necessarily correlate and trade-offs can occur [20,21,22]. This argument grows even stronger when the scope of the study is expanded to also include social and economic impacts.

2. Aim and Scope

This study expands on the review by Lazarevic and Martin [16] by expanding from biofuels to bio-based products in general, and from environmental impacts to sustainability indicators. Our aim, then, is to investigate to what extent important sustainability indicators are already used in the life cycle studies of bio-based products. We also discuss how LCSA can be expanded or improved in order to better contribute to the transition to a sustainable bio-based economy.

The scope of our investigation is limited to scientific publications between 2010 and 2015. We focus on assessments that are relevant to decisions made in Sweden, i.e., assessments of products that are produced or used in Sweden. The discussion on how LCSA can be improved is relevant also beyond the Swedish decision-making context.

The target audience of the article is the scientific community, practitioners who seek tools for evaluating the value chains of bio-based products, and decision-makers in industry and governmental institutions with a drive to understand what sustainability aspects are most important to consider in the development, production, and promotion of bio-based products.

3. Methodology

3.1. Identifying Important Sustainability Indicators

To investigate to what extent relevant sustainability indicators are used in life cycle studies, we first need to establish which indicators are important. There is no objective truth regarding what impacts should be included in a sustainability assessment. Instead, the perception regarding the importance of impacts and indicators is subjective. In the context of this paper, we combine stakeholder processes in order to identify prominent indicators. We use the following literature to establish what environmental and social indicators are important in sustainability assessments in general:

- impacts addressed by the planetary boundaries (PB) framework [23],

- the default list of impact categories in the European guide for Product Environmental Footprints [24], and

- impacts covered by the United Nations Environmental Programme and Society of Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry UNEP-SETAC Life Cycle Initiative guide for social life cycle assessment [25].

The planetary boundaries are chosen because of the widespread impact of this framework. We chose to use the guides for Product Environmental Footprint (PEF) and UNEP-SETAC SLCA because each of them is a product of a process involving a broad range of researchers involved in life cycle studies, and in the case of PEF, many stakeholders are involved as well.

We also carried out an ‘Open Space’ workshop (OSW) with experts in Sweden to identify and validate important indicators in the sustainability assessments of bio-based products. This serves the purpose of capturing aspects that are specific to bio-based products and/or to the Swedish context. Information on how the OSW was carried out in will be provided later in this paper.

Life cycle sustainability assessments include the social, environmental, and economic pillars of sustainability. However, the aforementioned approaches and frameworks do not cover the economic dimension. Thus, in addition to the indicators from these sources, we claim the life cycle cost to be an important sustainability indicator. This is the only economic indicator in the LCSA framework presented by Klöpffer [10]. It can be regarded as relevant because environmentally preferable products often have a higher acquiring cost, but can be cheaper over the span of a life cycle due to, for example, lower energy demand; see, e.g., Klöpffer and Ciroth [26]. Another reason is that the competitiveness of sustainable products on the market depends on their production costs [27]. Bio-based products often compete with cheaper alternatives, and an assessment of the production cost may be important in order to estimate what market penetration is possible. However, it has been argued that the life cycle cost indicator might not be sufficient to assess the economic dimension of sustainability [13], as it does not reflect the extent to which products affect the economic capital available for future generations [28]. Ekvall et al. [29] also demonstrated that economic sustainability can include aspects such as business opportunities and business risks.

3.2. Open Space Workshop

Open Space is a self-organizing technique that aims to generate creativity and informal discussion on a common theme [30]. Open Space workshops begin without a fixed agenda beyond this overall theme; specifying the agenda is instead one of the tasks assigned to the workshop participants. Ekvall et al. [29] previously used this method to identify important indicators and research questions in a LCSA of a 50-km pipeline for residual heat.

Invitations to our Open Space workshop were distributed mainly to researchers and industry practitioners in Sweden. The 19 participants who attended the workshop were primarily researchers in academia, institutes, and industry, with a background in environmental life cycle assessment (LCA) or energy systems analysis.

At the beginning of the workshop, the participants generated ideas for important sustainability aspects and indicators. After an initial allotted time for individual brainstorming, the participants formed five small groups, each of which selected three to five sustainability aspects or indicators that they considered important for assessments of bio-based products. The ideas were presented for the rest of the workshop participants and posted on a wall, and the overlaps were eliminated. From these aspects and indicators, the participants selected eight for in-depth group discussions with an aim to agree on why the indicator is important, and on what aspects or indicators should be considered and accounted for in a sustainability assessment of bio-based products.

At the end of the workshop, each participant was given six yes-votes and three no-votes to freely distribute among all of the ideas for sustainability indicators, in addition to all of the aspects identified in the previous group discussions. We interpreted the result of the voting as an indication of what the workshop participants considered important to account for in a sustainability assessment of bio-based products.

3.3. Inventory of Existing Life Cycle Studies

We performed a systematic literature review (cf. [16,31]) to identify what sustainability indicators are included in scientifically published life cycle studies. This included LCSAs, but also LCAs, SLCAs, and LCCs.

We used a Boolean string to find peer-reviewed publications in the Scopus database (www.scopus.com). This string included the following terms (see Supplementary material for the exact Boolean search strings):

- “bio”, “biomass”, and “bio-based”, because they are common words in discussions of bio-based products,

- “forest” and “wood” because forestry is an important industry in Sweden,

- “bioenergy”, “biofuel”, “biogas”, “biodiesel”, “ethanol”, Hydrogenated vegetable oil “HVO” and Fatty Acid Methyl Esters “FAME”, because they denote the most common biofuels in Sweden [6], and

- “district heating”, because this is an important sector for the use of solid biofuel.

The abstracts found were reviewed to find papers that applied at least a cradle-to-gate perspective. These included more than 900 LCAs. In order to facilitate the analysis of the papers, we excluded LCA papers that did not have any co-author from a Swedish research institution. We gave priority to research at Swedish institutions because it is often funded by the Swedish government or industry, which are likely to have an interest in the feedstock, processes and products that are relevant for the Swedish market, which limited the number of studies to 63.

The number of LCSAs, SLCAs, and LCCs was much smaller, and we included not only papers with contributions from Swedish institutions, but also from countries that are important for imports from and/or exports to Sweden of bio-based products, including: Norway, the United Kingdom (UK), Germany, Finland, Denmark, the Netherlands, Russia, the United States of America (USA), Poland, Portugal, Latvia, Estonia, Italy, China, Brazil, Australia, Indonesia, Ukraine, and Lithuania; see information on trade statistics; see e.g., Swedish Energy Agency [6] and SLU [32]. See more information in Table A1, Table A2, Table A3 and Table A4 Appendix A.

The selected papers were reviewed, and key information about each paper was compiled, including the goal of the study, indicators, methodological considerations, system boundaries, stakeholders, etc. This information was collected in a separate matrix for LCAs, SLCAs, LCCs, and LCSAs (see Supplementary materials for more details). We used it to determine the extent to which important sustainability indicators are considered in the studies. Furthermore, we merged some indicators. For example, we included assessments of changes in soil organic carbon in the broader category “direct land use change”. All of the indicators related to toxicity (e.g., human and freshwater toxicity) were grouped as “toxicity potential”.

4. Results

4.1. Important Indicators

For the context of this paper, we identified the following sustainability indicators and aspects to be important, besides the life cycle cost:

- from the PB framework [23]: climate change, stratospheric ozone depletion, chemical pollution, atmospheric aerosol concentration, nitrogen and phosphorus emissions, acidification of oceans, freshwater consumption, land-system change, and biodiversity loss;

- from the PEF guide [24]: climate change, ozone depletion, freshwater eco-toxicity, human toxicity (cancer and non-cancer impacts), emissions of particulate matter, human health impacts of radiation, photochemical ozone formation, acidification, eutrophication (terrestrial and aquatic), water depletion, depletion of fossil and mineral resources, and land transformation;

- from the UNEP-SETAC guide for SLCA [25]:

- ⚪

- impacts on workers: freedom of association, child labor, fair salary, working hours, forced labor, discrimination, health and safety, and social benefits and security;

- ⚪

- impacts on local community: access to material and immaterial resources, delocalization and migration, cultural heritage, safe and healthy living conditions, indigenous rights, community engagement, local employment, and secure living conditions;

- ⚪

- impacts on consumers: health and safety, feedback mechanisms, consumer privacy, transparency, and end-of-life responsibility;

- ⚪

- impacts on other value-chain actors: fair competition, social responsibility, supplier relationships, and intellectual property rights; and

- ⚪

- impacts on society overall: public commitments to sustainability issues, contribution to economic development, the prevention and mitigation of armed conflicts, technology development, and corruption.

- from the Open Space workshop [33] (see Table 1): climate change, biodiversity, working conditions, water use, ecosystem functions, and the use of various resources.

Table 1. Sustainability aspects identified by the participants in the Open Space workshop as potentially important to include in a sustainability assessment of bio-based products, and the result of the voting indicating which indicators were considered important [33].

Table 1. Sustainability aspects identified by the participants in the Open Space workshop as potentially important to include in a sustainability assessment of bio-based products, and the result of the voting indicating which indicators were considered important [33].

There is a large overlap between the PB framework and the impact categories in the PEF guide, because both focus on environmental sustainability and its impacts. The overlap is clear in the impact categories of climate change and ozone depletion. Ocean acidification is closely linked to climate change, since carbon dioxide emissions drive both. Chemical pollution and aerosols in the PB framework can affect the climate, but also dominate the toxicity impacts in the PEF guide. Eutrophication is dominated by emissions of nitrogen and phosphorus.

The PB framework and the PEF guide also differ on some points. The PB indicator for water use relates to the global consumptive use of freshwater, while the PEF indicator takes regional water scarcity into account. The PB indicator for particles includes solid and liquid particles that reside in the atmosphere, while the PEF indicator focuses on solid particles that are emitted to the atmosphere. The PEF indicator for land transformation focuses on changes in organic soil content, while the corresponding indicator in the PB framework has a broader scope related to the function, quality, and spatial distribution of the land cover. This has implications for biodiversity, which also is an explicit indicator in the PB framework, but is not included in the PEF impact categories. The PEF guide, on the other hand, includes more detailed indicators that are related to toxicity impacts and also several impacts that are not in the PB framework, such as: ionizing radiation, photochemical ozone creation, and the depletion of resources other than water.

The results from the Open Space workshop, with its focus on impacts related to bio-based products and the Swedish context, also strongly overlaps the PB framework and PEF guide, because the indicators identified as important are dominated by environmental aspects. However, note that the workshop participants identified biodiversity as one of the top environmental indicators for sustainability assessments of bio-based products, indicating that the impact categories listed in the PEF guide might not be enough for this purpose.

The indicator “working conditions” was the non-environmental aspect that was given top priority in the workshop. This indicator really includes a broad range of aspects and impacts. The UNEP-SETAC guide for SLCA, for example, divides work-related social aspects into the sub-categories Freedom of Association and Collective Bargaining, Child Labor, Fair Salary, Working Hours, Forced Labor, Equal opportunities/Discrimination, Health and Safety, and Social Benefits/Social Security.

Notably, the only clearly economic indicator that was identified as even potentially important is not life cycle cost, but regional value creation. This indicator also received a few votes in the end.

4.2. Life Cycle Studies Identified

Our literature search resulted in more than 100 scientifically published life cycle studies of bio-based products: 63 LCAs, 30 LCCs, seven SLCAs, and six LCSAs. Most of these were assessments of products produced from wood or food crops (such as cereals and vegetable oils), but the literature also covered the assessment of products made from several other biological feedstock materials (Table 2). In many cases, the biological material was part of an assessment that also included other materials. In some cases, the exact feedstock material was not clear in the published paper. In several cases, the articles identified in the literature review applied more than one of the life cycle methods, i.e., two or three of the LCA, LCC, and SLCA methods (see e.g., [34,35,36]). In this case, the feedstock type and product type in Table 2 and Table 3 were applied to only one column. For those reviewing all three tools, these were applied in the LCSA column, and for those reviewing environmental and economic tools, these were applied in the LCA column.

Table 2.

Type of feedstocks in the life cycle studies found in the literature review. Figures shown in parenthesis, e.g., (+10), refer to studies that include the biological feedstock as one of two or more feedstock types. LCA: life cycle assessment; LCC: life cycle costing; LCSA: life cycle sustainability assessments; SLCA: social life cycle assessments.

Table 3.

Type of products assessed in the different methods from the literature review.

A majority of the studies were LCAs or LCCs of energy products, but a broad range of other products were also assessed (Table 3). Energy products included various biofuels (e.g., ethanol, biogas, and Fischer–Tropsch diesel) and heating systems (e.g., district heating, pellets, and briquettes). Construction products included individual products, such as coatings, as well as whole building systems. Commodities included products such as bioplastics, cups, and fertilizers.

The products assessed are produced in various regions of the world. Approximately a quarter of the LCA studies and the majority of the LCC studies were assessments of products produced outside Europe. The SLCAs, for example, include products produced in Brazil [37,38], Indonesia [39], Australia [40,41], China [34,41], and the UK [42], as well as France, the USA, and Lithuania [37]. The LCSAs were primarily of European origin, but examples from China [34] and Mexico [35] were also present. More details about the distribution of the literature can be found in the Supplementary Materials.

4.3. Indicators Present in Life Cycle Assessments

Climate change is accounted for in all 63 LCA papers in our review (see Table 4). Energy use is also included in most LCAs. Acidification and eutrophication are both included in about half of the studies. Many studies also include direct land use and/or land use change. The former is primarily calculated as land occupation in square meters, while the latter usually focus on changes in the organic carbon content of the soil, as proposed in the PEF guide (and ultimately related to greenhouse gas emissions). Overall, though, the LCAs of bio-based products typically include few impact categories.

Table 4.

Environmental impact categories included in the 63 LCA publications and their explicit (exp.) or implicit (imp.) importance according to the planetary boundaries (PB) framework [23], the European Union (EU) guide to Product Environmental Footprints (PEF) [24], and our Open Space workshop (Table 1).

Compared to the environmental impacts and indicators that we identified as important, nearly all of the important indicators are covered in at least one case study. However, there is a divergence between what impacts are important, and how often they are used. Climate change and water use or depletion was explicitly listed as a significant impact in all three sources: the PB framework, the PEF guide, and the Open Space workshop. Climate change was included in all of the LCAs, but only two case studies accounted for water depletion. Acidification, which neither the PB framework or the Open Space workshop listed as very important, was included in more than half of the LCAs. Ecosystem quality, resource use, and indirect land use change are important according to two or all three sources, but were only included in very few scientifically published LCAs. Impacts on biodiversity were explicitly mentioned as important in the PB framework and were one of the top-priority indicators according to the Open Space workshop; still, it was not accounted for in any of the LCAs in our literature review.

Only eight of the 63 LCA articles included in our literature review provide reasons for the choice of impact categories. Five studies specified the product type (e.g., biofuel or fertilizer) as the cause of the selection, while one study also specified the biomass type (i.e., Jatropha) as the cause of selection.

None of the studies justified their choices through referring to the geographical context of the assessment. Which indicators are important can otherwise depend on where in the world the biomass is extracted and converted into products. For example, Lazarevic and Martin [16] indicated that environmental challenges in regions outside of Sweden can be different to those in regions that are more commonly assessed with LCA (Europe and USA), and that the choice of impact categories normally coincides with European environmental problems. The geographical context can significantly affect the technique and technology used, and how the bio-based product is treated at the end-of-life. It can also affect the impacts of a specific environmental intervention (emission or resource extraction).

4.4. Indicators Present in LCCs

It is clear from the number of LCCs found that life cycle costs are included in many LCA studies. Of the 30 identified LCCs, 17 were included in studies that combined it with LCA; only 13 solely reviewed the LCC. Economic indicators included the life cycle cost, which were shown as different monetary values per functional unit, and other economic indicators to show the economic viability and sustainability of the different systems. While most studies reviewed the life cycle cost from a producer’s (company) perspective, several studies also outlined the societal costs and benefits when comparing different technologies. Similar to the indicator “regional value creation” identified in the OSW, these studies took a larger perspective in order to understand the implications of regional production and consumption.

4.5. Indicators Present in Social LCAs

Several of the seven identified SLCAs (c.f. [34,37,38,39,40,41,42]) used the UNEP-SETAC guide [25] as the basis for their choice of impact categories. Furthermore, Ekener-Petersen et al. [37] used the Social Hotspots Database, where the categories are also based on the UNEP-SETAC guidelines, although they were somewhat adjusted. The other studies defined their own impacts categories. While the number of aspects or impact categories accounted for differences between the studies, working conditions and socio-economic repercussions, such as local employment, food security, and energy security, are reoccurring. Other aspects such as human rights (e.g., indigenous rights, child labor, etc.), governance (e.g., corruption, public commitments to sustainability, etc.) and cultural heritage (e.g., land acquisition, community engagement, etc.) are also addressed in several studies. The social aspects assessed in the articles reviewed cover both positive and negative impacts. Positive impacts relate, for example, to the increase in numbers of jobs (e.g., [38,42]) or public commitment to the sustainability of businesses [39].

All of the articles covered impacts on the stakeholder groups, or “workers”, which was indicated as important both in the UNEP-SETAC guidelines and in the results from our Open Space workshop (Table 1). All of the papers also included impacts on the “local community”. Impacts on the society at large and value chain actors are covered in only a selected few of the studies; c.f. [34,37,39]. The stakeholder categories were not explicitly selected and justified in most of the case studies reviewed. It is also important to note that the reviewed case studies primarily covered stakeholders who were involved in the production phase of the life cycle.

4.6. Indicators Present in Life Cycle Sustainability Assessments

The six LCSA articles found in the literature review [34,35,43,44,45,46] each applied in total between eight and 29 indicators in the assessment of environmental, economic, and social sustainability. A total of eight environmental impact categories were included in the studies reviewed: climate change, energy use, acidification, eutrophication, abiotic depletion, photochemical oxidant creation, toxicity, and particulate emissions. All of these were also included in multiple LCA studies (see Table 4). All of the articles covered climate change. Other commonly used environmental impact categories included acidification and energy use. Eutrophication, abiotic depletion, photochemical oxidant creation, toxicity, and particle emissions were less frequently used. All of the environmental impact categories found in the LCSA studies were recommended in the PEF guide. Most of them are also part of the PB framework, although the latter does not address abiotic depletion. Similar to the results from the review of LCA studies, none of the LCSA studies accounted for biodiversity, although both the OSW and PB frameworks identified these as important.

The LCSAs included, in total, four economic indicators. Life cycle cost was the most prevalent of these. Other economic indicators included investment cost and net present value. The social sustainability was assessed using a range of quantitative and qualitative indicators. The most common indicators in the LCSA studies reflected different aspects of accidents/safety risks, economic development, and education. Keller et al. [44] also accounted for impacts on a higher systems level through the indicator “socio-economic repercussions”. Furthermore, Santoyo-Castelazo and Azapagic [35] used qualitative indicators such as public acceptability and diversity of supply. They modeled health impacts through the use of the indicator “human health potential”, and suggested that global warming potential and abiotic resource depletion be used to account for social impacts on future generations. This creates a link between LCA and SLCA in the LCSA.

Many of the studies justified their choice of impact categories and indicators. The majority of the studies used stakeholder input in order to identify relevant indicators and aspects for the LCSA. Several of the studies discussed the challenges of combining all three pillars. These challenges were primarily related to developing a methodology for several of the impacts and indicators, combining quantitative and qualitative indicators, and adapting the assessments to the objects under review.

5. Discussion

5.1. Why Important Indicators are Missing

Our literature review suggests that the current practices of impact category selection for LCAs of bio-based products, and for the environmental dimension of LCSAs, focus on a limited, reoccurring set of indicators with limited justifications provided. These results are coherent with the recently published review of LCAs on biofuels in Sweden [16].

There is a discrepancy between how often an impact category is used in the LCAs, and how important it is according to the sources we have used. In particular, water depletion, ecosystem quality, indirect land use change, and biodiversity are important according to two or all three of our sources, and also implied by, for example, Lewandowski [8] and O’Brien et al. [9]. Still, they are excluded from most or all of the published LCAs. Impact categories that are less clearly important for bio-based products, e.g., acidification impacts, are included in a much larger number of studies. This suggests that the choice of impact categories in LCAs of bio-based products is not primarily decided by the importance of the environmental impact.

A simple explanation for the discrepancy between the importance and frequency of the indicators would be that the indicators we identified as important in our project are, in fact, not really that important. This explanation is contradicted by, for example, the United Nations (UN) Sustainable Development Goals, which state that water-use efficiency should substantially increase, and water scarcity should be addressed in order to substantially reduce the number of people suffering from water scarcity [47]. They also call for urgent and significant actions in order to reduce the degradation of natural habitats and halt the loss of biodiversity, including the integration of ecosystem and biodiversity values into national and local planning [48]. From the Swedish perspective, water scarcity is not yet an urgent matter in most parts of the country; however, the national environmental objective related to groundwater mentions the increased demand for, and hence pressure, on groundwater reservoirs [49]. One of the 16 national environmental objectives focuses entirely on biodiversity [50], and another four focus on land use and its impacts on ecosystems [51,52,53,54].

Another explanation for why important impact categories and indicators were excluded would be that no methods (or data) exist that allow for including all of them in an LCA. This is contradicted by all of the important indicators, except biodiversity, being included in at least one study. Methods also exist for taking impacts on biodiversity into account [55,56]. Hence, rudimentary methods, at least, exist to account for all of the important environmental impacts in LCAs. However, data availability in order to allow for the review of certain systems will need to be improved; see e.g., discussions by Martin and Brandão [57].

A more plausible explanation for why several important environmental indicators are often missing in the LCAs is that the methods that exist generate results that are regarded as poor indications of the actual impacts. For example, several of the studies recognized the importance of biodiversity, but referred to methodological immaturity for the exclusion of the indicator; see also [55,56].

The existing methods can also be difficult to apply. Indirect land use change can, for example be quantified through the use of the general equilibrium model from the Global Trade Analysis Project (GTAP); see Kløverpris et al. [58]. However, learning to run such a model might require more time and resources than are available for a specific LCA.

All of the SLCAs include impacts on workers, which is the stakeholder group that was given the highest priority in the Open Space workshop. This is consistent with the finding of Kühnen and Hahn [15] that indicators related to workers, in particular their health and safety, are the most common type of indicators in the global SLCA literature. The small total number of published SLCAs and LCSAs means that no social indicator is included in a large number of life cycle studies of bio-based products. This might be because the expertise needed to carry through SLCAs is still scarce, and/or because of a lack of mature methods. The latter reason is supported by three of the seven SLCAs having the explicit aim of developing the SLCA methodology.

5.2. The Need for Improved Indicator Modeling Methods

The discussion above indicates a need for the continued development and dissemination of operational methods in order to model specific, important impacts. This need concerns several environmental impacts and indicators, in particular water depletion, ecosystem quality, indirect land use change, and biodiversity.

As stated in Section 4.3, the impacts of a specific emission or resource extraction can significantly vary, depending on where it occurs. This may be accounted for through spatially explicit impact assessment methods. Lazarevic and Martin recommended taking regional differences into account when reviewing impacts in a Swedish context [16] through using, e.g., the Swedish Environmental Objectives [51]; however, the use of such methods is still not common practice in LCA databases [16,22].

The need for improved life cycle impact assessment methods includes social impacts in general, and impacts on workers in particular. Social impacts also depend on the geographical context. Our study takes a Swedish perspective, which includes a well-developed social welfare system; as a result, negative social impacts might not be as important to address as in other regions. However, the biomass that is employed to produce products consumed in Sweden is often sourced from other parts of the world, thus, it has implications that extend outside of Sweden [59,60]. An accurate assessment of the social sustainability needs to take this into account.

There is also a need for development of methods in order to assess the economic impacts, and associated indicators. The relevance of the life cycle cost as an indicator was that the competitiveness of a product depends on its production costs [27], and that environmentally preferable products often have a higher acquiring cost, but can be cheaper to use because of lower energy demand [26]. This indicates the need for two different economic cost indicators: a cradle-to-consumer calculation of the costs of production and distribution, and a life cycle calculation of the costs for the consumer. In addition, as indicated in Section 3.1, operational methods should perhaps be developed and disseminated for estimating the business risks and opportunities [29], and the impact of the product on the economic capital of future generations [28].

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at http://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/10/2/547/s1. Excel File: The excel file includes details from the matrices produced to document the articles reviewed in the literature review for the LCA, LCC, SLCA and LCSA articles.

Acknowledgments

The research in this project has been funded through the Swedish Research Council for Sustainable Development (FORMAS Grant Number 2015-14057). The final analysis and writing of the paper was also co-funded through the EU ERA-Net Sumforest project BenchValue (Formas Grant Number 2016-02113). The authors would also like to thank participants in the open space workshop for their participation, and the valuable input provided by Miguel Brandão to further develop the article. Finally, we would like to acknowledge the support provided by Anja Karlsson and Albin Pettersson of IVL in the literature review conducted for this research project.

Author Contributions

Michael Martin, Frida Røyne and Tomas Ekvall conceived and designed the study methodology and contributed to the primary share of the article writing. Åsa Moberg contributed in the SLCA sections, revisions and discussions. All authors were involved in the data collection, revisions and study design.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funding sponsors had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, nor in the decision to publish the results.

Appendix A. Literature Search Details

The following subsections provide details on the literature search, terms used for the searches used to identify the articles in Scopus and details about input into the matrices.

Appendix A.1. Life Cycle Assessment (LCA)

Table A1.

LCA literature search specifications.

Table A1.

LCA literature search specifications.

| Document Search Settings | Specification |

|---|---|

| Boolean string (article title, abstract, keywords) | “LCA” OR ”life cycle assessment” OR ”life cycle analysis” AND “bio” OR “biomass” OR “biobased” OR “forest” OR “wood” OR “biofuel” OR “biodiesel” OR “biogas” OR “ethanol” OR “HVO” OR “FAME” OR “bioenergy” OR “district heating” |

| Date range (inclusive) published | 2000 to 2015 |

| Country/territory limited to | Sweden |

Appendix A.2. Life Cycle Sustainability Assessment (LCSA)

Table A2.

LCSA literature search specifications.

Table A2.

LCSA literature search specifications.

| Document Search Settings | Specification |

|---|---|

| Boolean string (article title, abstract, keywords) | “Life Cycle Sustainability Assessment” OR ”life cycle sustainability analysis” OR ”life cycle” OR “sustainability assessment” OR LCSA OR “sustainability analysis” OR “Economic” OR “social” OR “environmental” AND “bio” OR “biomass” OR “biobased” OR “forest” OR “wood” OR “biofuel” OR “biodiesel” OR “biogas” OR “ethanol” OR “HVO” OR “FAME” OR “bioenergy” OR “district heating” |

| Date range (inclusive) published | 2000 to 2015 |

| Country/territory limited to | Sweden, Norway, UK, Germany, Finland, Denmark, The Netherlands, Russia, USA, Poland, Portugal, Latvia, Estonia, Italy, China, Brazil, Australia, Indonesia, Ukraine, Lithuania. |

Appendix A.3. Life Cycle Costing (LCC)

Table A3.

LCC literature search specifications.

Table A3.

LCC literature search specifications.

| Document Search Settings | Specification |

|---|---|

| Boolean string (article title, abstract, keywords) | “Life Cycle” OR “LCC” OR ”life cycle cost” OR ”life cycle costing” OR “Life Cycle Cost Analysis” OR LCCA OR “Life cycle cost assessment” OR “Life Cycle Economic Analysis” AND “bio” OR “biomass” OR “biobased” OR “forest” OR “wood” OR “biofuel” OR “biodiesel” OR “biogas” OR “ethanol” OR “HVO” OR “FAME” OR “bioenergy” OR “district heating” |

| Date range (inclusive) published | 2000 to 2015 |

| Country/territory limited to | Sweden, Norway, UK, Germany, Finland, Denmark, The Netherlands, Russia, USA, Poland, Portugal, Latvia, Estonia, Italy, China, Brazil, Australia, Indonesia, Ukraine, Lithuania. |

Appendix A.4. Social Life Cycle Assessment (SLCA)

Table A4.

SLCA literature search specifications.

Table A4.

SLCA literature search specifications.

| Document Search Settings | Specification |

|---|---|

| Boolean string (article title, abstract, keywords) | “Life Cycle” OR “SLCA” OR ”social life cycle” OR ”life cycle assessment” OR “Socio-economic” OR S-LCA OR “life cycle analysis” OR “LCA” OR “social impacts” OR “social sustainability” AND “bio” OR “biomass” OR “biobased” OR “forest” OR “wood” OR “biofuel” OR “biodiesel” OR “biogas” OR “ethanol” OR “HVO” OR “FAME” OR “bioenergy” OR “district heating” |

| Date range (inclusive) published | 2000 to 2015 |

| Country/territory limited to | Sweden, Norway, UK, Germany, Finland, Denmark, The Netherlands, Russia, USA, Poland, Portugal, Latvia, Estonia, Italy, China, Brazil, Australia, Indonesia, Ukraine, Lithuania. |

Appendix A.5. Limitations for the Literature Search

The search was also limited to a set of specified feedstock materials and biomass value chains. In addition to the general keywords “bio”, “biomass” and “biobased”, the specification is based on three Swedish bio-based markets:

Appendix A.5.1. The Forest Product Market (Forest Products are Here Defined as Products Derived from Forest Biomass)

Sweden is covered by almost 70% forest [61], and forestry is an important industry in Sweden. Sweden has both export and import of forest products (round wood, chips, pellets, wooden products (e.g., particle boards, paper, and pulp)) with several countries (more than 5000 M SEK per year: Norway, Germany, Finland, Poland, Denmark, Latvia, Estonia, The Netherlands, China, Russia, UK, Portugal, USA, and Italy) [62]. The keywords “forest” and “wood” were therefore added to the Boolean string.

Appendix A.5.2. The Biofuel Market

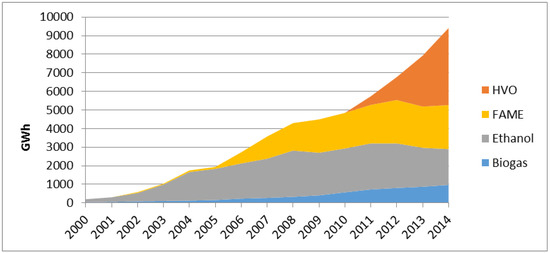

The biofuel market in Sweden mainly consists of three markets: a local (Swedish); biogas, a regional (European); biodiesel, and a global; ethanol [63]. The keywords “biofuel*”, “biogas”, “biodiesel” and “ethanol” were therefore added to the Boolean string. Figure A1 shows the biofuels with the highest consumption volumes in Sweden. Based on the figure, the keywords “HVO” and “FAME” were also added to the Boolean string.

Figure A1.

Biofuel consumption in Sweden from 2000 to 2014 (shown in GWh annually). Figure from [60].

Appendix A.5.3. The Bioenergy Market

Main energy sources for district heating are residues from the forest industry, forest residues, recovered waste wood, refined wood fuels, municipal and industrial biogenic waste, bio-oils, and peat. Bioenergy also plays an important role in industry and electricity production [64]. Sweden also imports waste, mainly from Norway and the UK, of which 85% goes to energy recovery [65]. The keywords “bioenergy” and “district heating” were therefore added to the Boolean string.

Appendix A.5.4. Date Range, Document Type, and Subject Areas

The project focuses on documents published 2000–2015.

Appendix A.5.5. The Swedish Context

The project focuses on research which is relevant for Swedish conditions. We therefore limited the literature review to articles written by one or more authors from a Swedish institution. Our rationale is that Sweden based authors (often) are financed by the Swedish state or industry. These have an interest in feedstock, processes and products relevant for the Swedish market. For LCC and SLCA, a limitation to Sweden resulted in too few studies. If this is the case, the scope can be broadened to include the countries that are most important in a Swedish import/export context of forestry products [62], biofuels [60,66,67] and waste [65]. These included Norway, UK, Germany, Finland, Denmark, The Netherlands, Russia, USA, Poland, Portugal, Latvia, Estonia, Italy, China, Brazil, Australia, Indonesia, Ukraine and Lithuania.

Appendix A.5.6. Criteria for Selection

From the studies identified from the literature searches above, only those studies meeting the following guidelines were chosen for the review. These included:

- (1)

- Following the LCA methodology (excluding LCI studies),

- (2)

- focusing on biomass value chains (for example, the waste for district heating should be (mainly) bio-derived),

- (3)

- involving case studies (e.g., no review studies, discussions) and

- (4)

- following a peer-review process.

Thereafter, each article abstract was reviewed to ensure that it was relevant for the study. As identified in the text, the articles were then reviewed and relevant information and details on the articles, and key information such as the goal of the study, methodological considerations, system boundaries, stakeholders, impact categories and specific aspects covered were compiled. The information was used to determine the extent and details of important sustainability aspects considered in LCA, LCC, SLCA and LCSAs applied to biomass value chains of relevance for Swedish conditions, see the Supplementary materials for a copy of the matrices for the respective life cycle based methods.

References

- EuropaBio. Building A Bio-Based Economy for Europe in 2020, EuropaBio Policy Guide; European Association for Bioindustries (EuropaBio): Brussels, Belgium, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Innovating for Sustainable Growth: A Bioeconomy for Europe; European Association for Bioindustries (EuropaBio): Brussels, Belgium, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- McCormick, K.; Kautto, N. The Bioeconomy in Europe: An Overview. Sustainability 2013, 5, 2589–2608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staffas, L.; Gustavsson, M.; McCormick, K. Strategies and Policies for the Bioeconomy and Bio-Based Economy: An Analysis of Official National Approaches. Sustainability 2013, 5, 2751–2769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Formas. Swedish Research and Innovation Strategy for a Bio-based Economy Report: R3:2012. Available online: http://www.formas.se/PageFiles/5074/Strategy_Biobased_Ekonomy_hela.pdf (accessed on 20 February 2018).

- Swedish Energy Agency. Drivmedel Och Biobränslen 2015—Mängder, Komponenter Och Ursprung Rapporterade I Enlighet Med Drivmedelslagen Och Hållbarhetslagen; ER 2016:12; Swedish Energy Agency: Stockholm, Sweden, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hedlund-de wit, A. An integral perspective on the (un)sustainability of the emerging bio-economy: Using the integrative worldview framework for illuminating a polarized societal debate. In Proceedings of the Integral Theory Conference, San Francisco, CA, USA, 18–21 July 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lewandowski, I. Securing a sustainable biomass supply in a growing bioeconomy. Glob. Food Secur. 2015, 6, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, M.; Schütz, H.; Bringezu, S. The land footprint of the EU bioeconomy: Monitoring tools, gaps and needs. Land Use Policy 2015, 47, 235–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kloepffer, W. Life cycle sustainability assessment of products. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2008, 13, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guinée, J.; Heijungs, R.; Huppes, G.; Zamagni, A.; Masoni, P.; Buonamici, R.; Ekvall, T.; Rydberg, T. Life cycle assessment: Past, present, and future. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 45, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finkbeiner, M.; Schau, E.M.; Lehmann, A.; Traverso, M. Towards life cycle sustainability assessment. Sustainability 2010, 2, 3309–3322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamagni, A.; Pesonen, H.-L.; Swarr, T. From LCA to Life Cycle Sustainability Assessment: Concept, practice and future directions. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2013, 18, 1637–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaubroeck, T.; Rugani, B. A revision of what life cycle sustainability assessment should entail: Towards modeling the Net Impact on Human Well-Being. J. Ind. Ecol. 2017, 21, 1464–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kühnen, M.; Hahn, R. Indicators in Social Life Cycle Assessment—A Review of Frameworks, Theories, and Empirical Experience. J. Ind. Ecol. 2017, 21, 1547–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarevic, D.; Martin, M. Life cycle assessments, carbon footprints and carbon visions: Analysing environmental systems analyses of transportation biofuels in Sweden. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 137, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Voet, E.; Lifset, R.J.; Luo, L. Life-cycle assessment of biofuels, convergence and divergence. Biofuels 2010, 1, 435–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, M.; Haufe, J.; Carus, M.; Brandão, M.; Bringezu, S.; Hermann, B.; Patel, M.K. A Review of the Environmental Impacts of Biobased Materials. J. Ind. Ecol. 2012, 16, S169–S181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Blottnitz, H.; Curran, M.A. A review of assessments conducted on bio-ethanol as a transportation fuel from a net energy, greenhouse gas, and environmental life cycle perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 15, 607–619. [Google Scholar]

- Janssen, M.; Xiros, C.; Tillman, A.M. Life cycle impacts of ethanol production from spruce wood chips under high-gravity conditions. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2016, 9, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pascual-González, J.; Guillén-Gosálbez, G.; Mateo-Sanz, J.M.; Jiménez-Esteller, L. Statistical analysis of the ecoinvent database to uncover relationships between life cycle impact assessment metrics. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 112, 359–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinmann, Z.J.N.; Schipper, A.M.; Hauck, M.; Huijbregts, M.A.J. How Many Environmental Impact Indicators Are Needed in the Evaluation of Product Life Cycles? Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 3913–3919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steffen, W.; Richardson, K.; Rockström, J.; Cornell, S.E.; Fetzer, I.; Bennett, E.M.; Biggs, R.; Carpenter, S.R.; de Vries, W.; de Wit, C.A.; et al. Planetary boundaries: Guiding human development on a changing planet. Science 2015, 347, 1259855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EC. Commission Recommendation of 9 April 2013 on the use of common methods to measure and communicate the life cycle environmental performance of products and organisations. European Commission (EC). Off. J. Eur. Union 2013, 54, 124. [Google Scholar]

- Benoît, C.; Mazijn, B. (Eds.) Guidelines for Social Life Cycle Assessment of Products—A Social and Socio-Economic LCA Code of Practice Complementing Environmental LCA and Life Cycle Costing, Contributing to the Full Assessment of Goods and Services Within the Context of Sustainable Development; United Nations Environment Programme: Paris, France, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Klöpffer, W.; Ciroth, A. Is LCC relevant in a sustainability assessment? Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2011, 16, 99–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannouf, M.; Assefa, G. Comments on the relevance of life cycle costing in sustainability assessment of product systems. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2016, 21, 1059–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jørgensen, A.; Herrmann, I.T.; Bjørn, A. Analysis of the link between a definition of sustainability and the life cycle methodologies. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2013, 18, 1440–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekvall, T.; Ljungkvist, H.; Ahlgren, E.; Sandvall, A. Participatory Life Cycle Sustainability Analysis; Report B2268; IVL; Swedish Environmental Research Institute: Stockholm, Sweden, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Owen, H. Open Space Technology: A User’s Guide, 3rd ed.; Berrett-Koehler Publishers: San Fransisco, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Zumsteg, J.M.; Cooper, J.S.; Noon, M.S. Systematic Review Checklist: A Standardized Technique for Assessing and Reporting Reviews of Life Cycle Assessment Data. J. Ind. Ecol. 2012, 16, S12–S21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- SLU. Forest Statistics 2015; Official Statistics of Sweden, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences (SLU): Genevå, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ekvall, T. Open Space Workshop on Sustainability Indicators for Bio-Based Products; Report B238; IVL Swedish Environmental Research Institute: Stockholm, Sweden, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, J.; Manzardo, A.; Mazzi, A.; Zuliani, F.; Scipioni, A. Prioritization of bioethanol production pathways in China based on life cycle sustainability assessment and multicriteria decision-making. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2015, 20, 842–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoyo-Castelazo, E.; Azapagic, A. Sustainability assessment of energy systems: Integrating environmental, economic and social aspects. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 80, 119–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Rosa, A.D.; Cozzo, G.; Latteri, A.; Recca, A.; Björklund, A.; Parrinello, E.; Cicala, G. Life cycle assessment of a novel hybrid glass-hemp/thermoset composite. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 44, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekener-Petersen, E.; Höglund, J.; Finnveden, G. Screening potential social impacts of fossil fuels and biofuels for vehicles. Energy Policy 2014, 73, 416–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, A.; Watanabe, M.D.B.; Cavalett, O.; Ugaya, C.M.L.; Bonomi, A. Social life cycle assessment of first and second-generation ethanol production technologies in Brazil. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2016, 23, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manik, Y.; Leahy, J.; Halog, A. Social life cycle assessment of palm oil biodiesel: A case study in Jambi Province of Indonesia. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2013, 18, 1386–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weldegiorgis, F.; Franks, D. Social dimensions of energy supply alternatives in steelmaking: Comparison of biomass and coal production scenarios in Australia. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 84, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Lei, T.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Y.X.; Shi, X.; Zaifeng, L.; Xiaofeng, H.; Zhang, Q. Economic, environmental and social assessment of briquette fuel from agricultural residues in China: A study on flat die briquetting using corn stalk. Energy 2014, 64, 557–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamford, L.; Azapagic, A. Life cycle sustainability assessment of UK electricity scenarios to 2070. Energ. Sustain. Dev. 2014, 2, 194–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, S.; Brandstetter, P.; Beck, T.; Fullana-i-Palmer, P.; Grönman, K.; Baitz, M.; Deimling, S.; Sandilands, J.; Fischer, M. An extended life cycle analysis of packaging systems for fruit and vegetable transport in Europe. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2013, 18, 1549–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, H.; Rettenmaier, N.; Reinhardt, G.A. Integrated life cycle sustainability assessment—A practical approach applied to biorefineries. Appl. Energ. 2015, 154, 1072–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colodel, C.M.; Kupfer, T.; Barthel, L.P.; Albrecht, S. R&D decision support by parallel assessment of economic, ecological and social impact—Adipic acid from renewable resources versus adipic acid from crude oil. Ecol. Econ. 2009, 68, 1599–1604. [Google Scholar]

- Vinyes, E.; Oliver-Solà, J.; Ugaya, C.; Rieradevall, J.; Gasol, C.M. Application of LCSA to used cooking oil waste management. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2013, 18, 445–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN a. Goal 6: Access to Water and Sanitation for All. United Nations, 2017. Available online: http://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/water-and-sanitation/ (accessed on 14 November 2017).

- UN b. Goal 15: Sustainably Manage Forests, Combat Desertification, Halt and Reverse Land Degradation, Halt Biodiversity Loss. United Nations, 2015. Available online: http://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/biodiversity/ (accessed on 14 November 2017).

- SEPA. Swedish Environmental Objectives. Swedish Environmental Objectives; Swedish Environmental Protection Agency (SEPA): Stockholm, Sweden, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- SEPA a. Objective 9. Good-Quality Groundwater. Swedish Environmental Protection Agency. 2017. Available online: http://www.miljomal.se/Environmental-Objectives-Portal/Undre-meny/About-the-Environmental-Objectives/9-Good-Quality-Groundwater/ (accessed on 14 November 2017).

- SEPA b. Objective 16. A Rich Diversity of Plant and Animal Life. Swedish Environmental Protection Agency. 2017. Available online: http://www.miljomal.se/Environmental-Objectives-Portal/Undre-meny/About-the-Environmental-Objectives/16-A-Rich-Diversity-of-Plant-and-Animal-Life/ (accessed on 14 November 2017).

- SEPA c. Objective 11. Thriving Wetlands. Swedish Environmental Protection Agency. 2017. Available online: http://www.miljomal.se/Environmental-Objectives-Portal/Undre-meny/About-the-Environmental-Objectives/11-Thriving-Wetlands/. (accessed on 14 November 2017).

- SEPA d. Objective 12. Sustainable Forests. Swedish Environmental Protection Agency. 2017. Available online: http://www.miljomal.se/Environmental-Objectives-Portal/Undre-meny/About-the-Environmental-Objectives/12-Sustainable-Forests/ (accessed on 14 November 2017).

- SEPA e. Objective 13. A Varied Agricultural Landscape. Swedish Environmental Protection Agency. 2017. Available online: http://www.miljomal.se/Environmental-Objectives-Portal/Undre-meny/About-the-Environmental-Objectives/13-A-Varied-Agricultural-Landscape/ (accessed on 14 November 2017).

- De Baan, L.; Curran, M.A.; Rondinini, C.; Visconti, P.; Hellweg, S.; Koellner, T. High-resolution assessment of land use impacts on biodiversity in life cycle assessment using species habitat suitability models. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 2237–2244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teixeira, R.F.M.; De Souza, D.M.; Curran, M.P.; Antón, A.; Michelsen, O.; Milá I Canals, L. Towards consensus on land use impacts on biodiversity in LCA: UNEP/SETAC Life Cycle Initiative preliminary recommendations based on expert contributions. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 112, 4283–4287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, M.; Brandão, M. Evaluating the Environmental Consequences of Swedish Food Consumption and Dietary Choices. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kløverpris, J.; Wenzel, H.; Nielsen, P.H. Life cycle inventory modeling of land use induced by crop consumption. Part 1: Conceptual analysis and methodological proposal. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2008, 13, 13–21. [Google Scholar]

- Harnesk, D.; Brogaard, S. Social Dynamics of Renewable Energy—How the European Union’s Renewable Energy Directive Triggers Land Pressure in Tanzania. J. Env. Dev. 2016, 26, 156–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, M.; Larsson, M.; Oliveira, F.; Rydberg, T. Reviewing the environmental implications of increased consumption and trade of biofuels for transportation in Sweden. Biofuels 2017, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SLU. Official Statistics of Sweden & Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences Umeå (SLU). In Forest Statistics 2015; The Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences: Uppsala, Sweden, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Swedish Forest Agency. Skogsstatistisk årsbok 2014 [Swedish Statistical Yearbook of Forestry]. Available online: https://www.skogsstyrelsen.se/globalassets/statistik/historisk-statistik/skogsstatistisk-arsbok-2010-2014/skogsstatistisk-arsbok-2014.pdf (accessed on 20 February 2018).

- Bioenergiportalen. Andelen Biodrivmedel ökar. [The Share of Biofuels Is Increasing]. Available online: http://www.bioenergiportalen.se/?p=1443 (accessed on 21 January 2015).

- Svebio. The Swedish Experience. How bioenergy became the largest energy source in Sweden. Available online: https://www.svebio.se/sites/default/files/Bioenergy%20in%20Sweden_web.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2016).

- SEPA. Import Och Export Av Avfall 2004–2013 [Import and Export of Waste 2004–2013. Swedish Environmental Protection Agency (SEPA). Available online: https://www.naturvardsverket.se/Sa-mar-miljon/Statistik-A-O/Avfall-import-och-export-2004-2013/# (accessed on 23 February 2016).

- Swedish Energy Agency. Analys Av Marknaderna FöR Biodrivmedel. Tema: Fordonsgasmarknaden. [Analysis of the Biofuel Markets. Theme: The Biofuel Market]. Available online: https://www.energimyndigheten.se/globalassets/nyheter/2013/analys-av-marknaderna-for-biodrivmedel.pdf 2013 (accessed on 24 February 2016).

- Swedish Energy Agency. Hållbara Biodrivmedel Och Flytande BiobräNslen 2014. [Sustainable Biofuels and Liquid Bioenergy 2014]. Available online: https://energimyndigheten.se.2014 (accessed on 23 November 2015).

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).