Peace with Hunger: Colombia’s Checkered Experience with Post-Conflict Sustainable Community Development in Emerald-Mining Regions

Abstract

:1. Introduction

“I was told by a senior executive in the mining emerald industry they had spent many millions of dollars, so that well-known princesses, princes and famous top models could wear a luxurious necklace. You are speaking in a different language—I said. Thank you for letting me know this but my heart cries for those single mothers in Muzo who cannot afford food for their children. All that money you are talking about is being spent abroad. We have not got a coin from that luxurious necklace” [1].

2. Governance and Sustainable Community Development

3. Case Study Selection and Methodology

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Contrasting Stakeholders’ Perceptions at All Levels of Governance

4.2. Perceptions at the Local Level of Governance

“When I first started the ‘guaqueo’, or informal mining, I used to exchange emeralds for groceries. Over the time, I was able to get some money that helped me pay my children’s education. Nowadays, there is no artisanal mining. Unfortunately, the government think we all are criminals. There are policies in place but those only applied to multinational companies. We were told we were not allowed to mine. We will be persecuted if we continue undertaking artisanal mining activities on informal basis. We need to have money to be able to mine. This is a very complex issue and we are witnessing the beginning of a huge social problem that will exacerbate in the coming years. Due to the loss of mining as a livelihood option, people are embarking on criminal activities. They do not have any other option. What do you do when you have no job and you are starving? You engage in illegal activities, right? If we do not diversify the economy, if we do not educate people, if we do not build capacity in other areas different from mining such as entrepreneurship, we will start witnessing the rising of the worse criminals in this region [1].”

“In the past, 100% of mining royalties were allocated to Muzo. Now with the new royalty system Muzo receives only between 20 and 30% of mining royalties. This money has been invested mainly in projects in potable water, education and health. Muzo is a producer area that deserves to have 100% of mining revenues and royalties. We disagree with the new system and decision made on the new royalty allocation system [34].”

“There is insufficient communication between us and the American mining company operating in Muzo. But we have managed to brainstorm some ideas and somehow collaborate for key initiatives in alignment with their social responsibility agenda. The local government has also encouraged the private sector to align with the local development plan. Otherwise, we will end up embarking on programs irrelevant for us. We hope the company helps us to provide locals with potable water. This is a huge challenge. We are also thinking of developing a tourism plan in collaboration with the American mining company. We want tourists to be able to access large mine sites and get a better understanding of emerald mining. Third, we are aiming at diversifying the economy through agriculture. However, we are very upset about this initiative because, the private company is not targeting communities adjacent to the mine site [34].”

4.3. Perceptions at the Regional and National Levels of Governance

“Universities and government organizations have come here to provide us with capacity-building. But you know what they do. They get our signatures to show they did the job and get credit at our expense. We need something of value in Muzo. For example, productive projects that target single mothers, widows and the elderly” [1].

“Some projects have been approved under the new royalty system. However, existing governance arrangement to access resources coming from mining revenues are difficult to access. When financial resources are allocated at the local level, they have already passed through so many hands that we got nothing at the end. We have proposed projects but usually our proposals have been thrown away. There is not an effective allocation of those resources” [1].

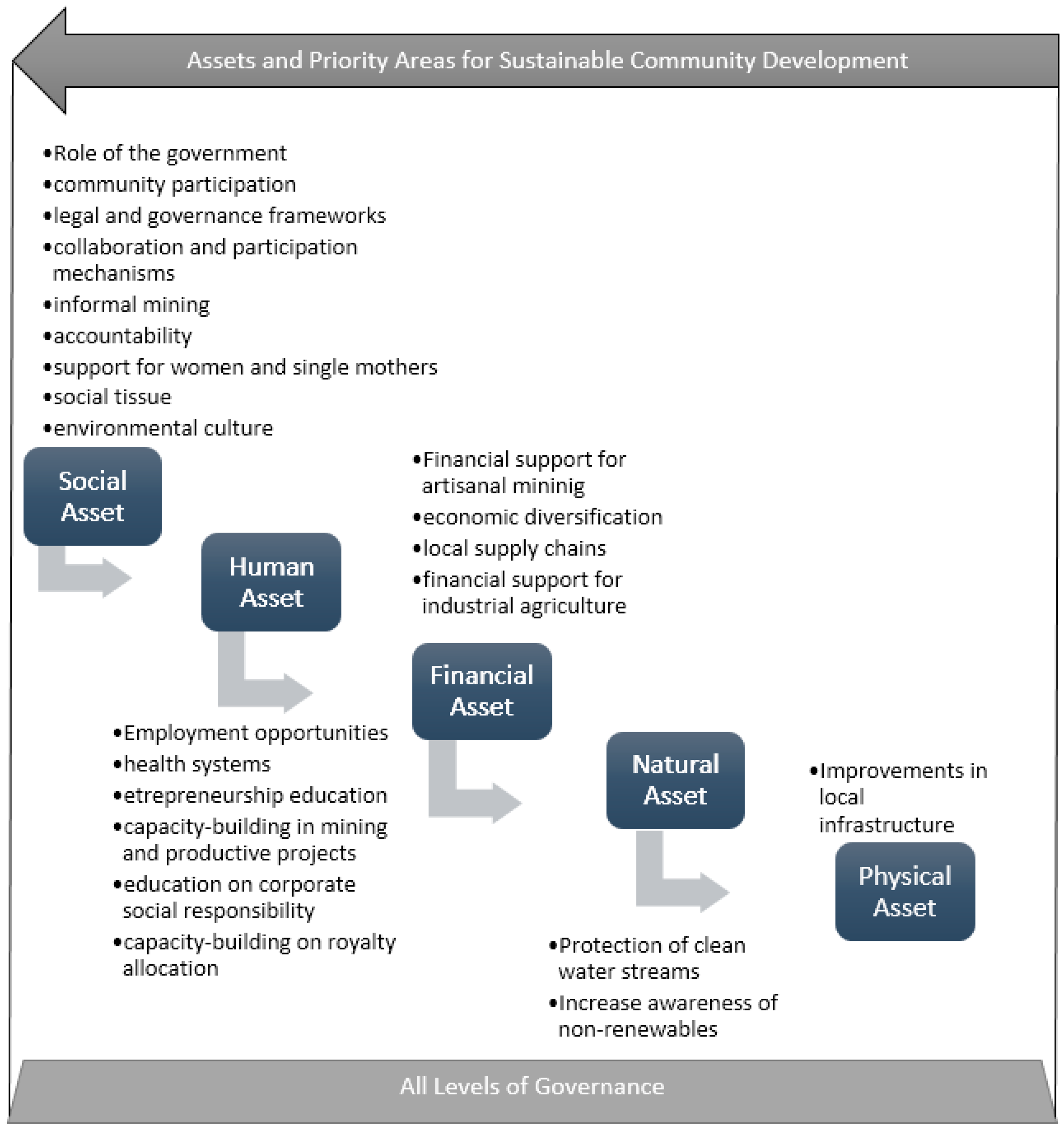

4.4. Collaborative Governance Approach to Sustainable Community Development in Resource Regions

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Community Members. Local Level of Governance; Focus Group Discussion: Muzo, Colombia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, J.S. Local Governance and the Dialectics of Hierarchy, Market and Network. Policy Stud. 2005, 26, 311–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Food Program (WFP). Fighting Hunger with Peace. 2017. Available online: https://www.wfp.org/stories/fighting-hunger-peace (accessed on 12 December 2017).

- Kwarteng, K. War and Gold: A Five-Hundred-Year History of Empires, Adventures, and Debt, 1st ed.; PublicAffairs: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, I. War! What Is It Good For?: Conflict and the Progress of Civilization from Primates to Robots; Farrar, Straus and Giroux: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Franco, I.B. Building Sustainable Communities: Enhancing Human Capital in Resource Regions. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Franco, I.; Ali, S. Decentralization, Corporate Community Development and Resource Governance: A Comparative Analysis of Two Mining Regions in Colombia. Extr. Ind. Soc. 2016, 4, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minnery, J. Stars and their Supporting Cast: State, Market and Community as Actors in Urban Governance. Urban Policy Res. 2007, 25, 325–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alizar, A.; Scott, R. Working at the Local Level to Support Sustainable Mining. Can. Min. J. 2009, 130, 24–25. [Google Scholar]

- Muthuri, J.N. Corporate Citizenship and Sustainable Development—Fostering Multi-Sector Collaboration in Kenya. J. Corp. Citizensh. 2007, 28, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warhust, A. Corporate Citizenship and Corporate Social Investment. J. Corp. Citizensh. 2001, 2001, 57–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Council on Mining and Metals (ICMM). Community Development Toolkit. 2005. Available online: https://www.icmm.com/news-and-events/news/articles/icmm-presents-updated-community-development-toolkit (accessed on 12 December 2017).

- Bond, C.J. Positive peace and sustainability in the mining context: Beyond the triple bottom line. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 84, 164–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Himley, M. Global mining and the uneasy neoliberalization of sustainable development. Sustainability 2010, 2, 3270–3290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Awuah-Offei, K.; Que, S.; Yang, W. Eliciting Drivers of Community Perceptions of Mining Projects through Effective Community Engagement. Sustainability 2016, 8, 658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, C.; Everingham, J.A.; Franks, D. Managing the Cumulative Impacts of Mining through Collaboration: The Moranbah Cumulative Impacts Group (MCIG); The University of Queensland: Brisbane, Australia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- International Council on Mining and Metals (ICMM). 10 Principles. 2003. Available online: http://www.icmm.com/our-work/sustainable-development-framework/10-principles (accessed on 12 December 2017).

- Liu, Q.; Yang, Z.; Wang, F. Conservation Policy-Community Conflicts: A Case Study from Bogda Nature Reserve, China. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mate, K. Capacity-Building and Policy for Sustainable Development Networking. Miner. Energy Raw Mater. Rep. 2001, 16, 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institute for Environment and Development (IED). Building Partnerships: Key Elements of Capacity Building; An Exploration of Experiences with Mining Communities in America Latina; Mining, Minerals and Sustainable Development; International Institute for Environmental Development: London, UK, 2001; Volume 33. [Google Scholar]

- Asamoah, E.F.; Zhang, L.; Liang, S.; Pang, M.; Tang, S. Emergy Perspectives on the Environmental Performance and Sustainability of Small-Scale Gold Production Systems in Ghana. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veiga, M.; Scoble, M.; McAllister, M.L. Mining with Communities. Nat. Resour. Forum 2001, 25, 191–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahiri-Dutt, K.; Slack, K.; Secretariat of the IGCP Programme; Baker, L.; Downs, T.J.; MaNeely, J.A.; Tambunan, T.; Iftekhar, M.S.; Franks, D.; Souza, W.; et al. How Can Revenues from Natural Resources Extraction Be More Efficiently Utilized for Local Sustainable Development? Nat. Resour. Forum 2009, 33, 245–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanzi, D. Capabilities, Human Capital and Education. J. Socio-Econ. 2007, 36, 424–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridge, G. Harnessing the Bonanza: Economic Liberalization and Capacity Building in the Mineral Sector. Nat. Resour. Forum 1999, 23, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milanez, B.; de Oliveira, J.A.P. Innovation for sustainable development in artisanal mining: Advances in a cluster of opal mining in Brazil. Resour. Policy 2013, 38, 427–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Oliveira, J.A.P.; Ali, S.H. Gemstone mining as a development cluster: A study of Brazil’s emerald mines. Resour. Policy 2011, 36, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, I. The Mineral Industry of Colombia. 2001. Available online: http://minerals.usgs.gov/minerals/pubs/country/2001/comyb01r.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2017).

- De la Hoz, J.V. Cerro Matoso y la Economía del Ferroníquel en el Alto San Jorge (Córdoba). Econ. Soc. 2009, 20, 41–58. [Google Scholar]

- Ragin, C.C. What is a Case? Exploring the Foundations of Social Inquiry; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, B.W.; Carroll, T. Civic Networks, Legitimacy and the Policy Process. Governance 1999, 12, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilson, G.M. Championing the Rhetoric? “Corporate Social Responsibility” in Ghana’s mining sector. Greener Manag. Int. 2006, 53, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Congreso de la Republica de Colombia. Constitución Política de Colombia; Congreso de la Republica de Colombia: Bogota, Colombia, 1991.

- Government Representatives. Local Level of Governance; Focus Group Discussion: Bogota, Colombia, 2017.

- Corporate Representatives. Focus Group Discussion, Muzo, Colombia, 2017.

- Government Representatives. Regional and National Level of Governance; Focus Group Discussion: Bogota, Colombia, 2017.

- Bebbington, A. (Ed.) Social Conflict, Economic Development and Extractive Industry: Evidence from South America, 1st ed.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

| Dimensions | Strengths and Opportunities | Weaknesses and Threats |

|---|---|---|

| Human |

|

|

| Community/Local |

|

|

| Natural |

|

|

| Economic |

|

|

| Infrastructure |

|

|

| Dimensions | Strengths and Opportunities | Weaknesses and Threats |

|---|---|---|

| Human |

|

|

| Community/Local |

|

|

| Natural |

| |

| Economic |

|

|

| Infrastructure |

|

|

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Franco, I.B.; Puppim de Oliveira, J.A.; Ali, S.H. Peace with Hunger: Colombia’s Checkered Experience with Post-Conflict Sustainable Community Development in Emerald-Mining Regions. Sustainability 2018, 10, 504. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10020504

Franco IB, Puppim de Oliveira JA, Ali SH. Peace with Hunger: Colombia’s Checkered Experience with Post-Conflict Sustainable Community Development in Emerald-Mining Regions. Sustainability. 2018; 10(2):504. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10020504

Chicago/Turabian StyleFranco, Isabel B., Jose A. Puppim de Oliveira, and Saleem H. Ali. 2018. "Peace with Hunger: Colombia’s Checkered Experience with Post-Conflict Sustainable Community Development in Emerald-Mining Regions" Sustainability 10, no. 2: 504. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10020504

APA StyleFranco, I. B., Puppim de Oliveira, J. A., & Ali, S. H. (2018). Peace with Hunger: Colombia’s Checkered Experience with Post-Conflict Sustainable Community Development in Emerald-Mining Regions. Sustainability, 10(2), 504. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10020504