Identifying Project Management Practices and Principles for Public–Private Partnerships in Housing Projects: The Case of Tanzania

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Conceptualization and Theoretical Basis: Innovation Diffusion Theory

3. Literature Review

3.1. Principles of PPP Project Implementation

3.2. Desirable CSFs for Project Management Projects and PPPs

3.3. Contextual Background—Tanzanian Specific PPPs

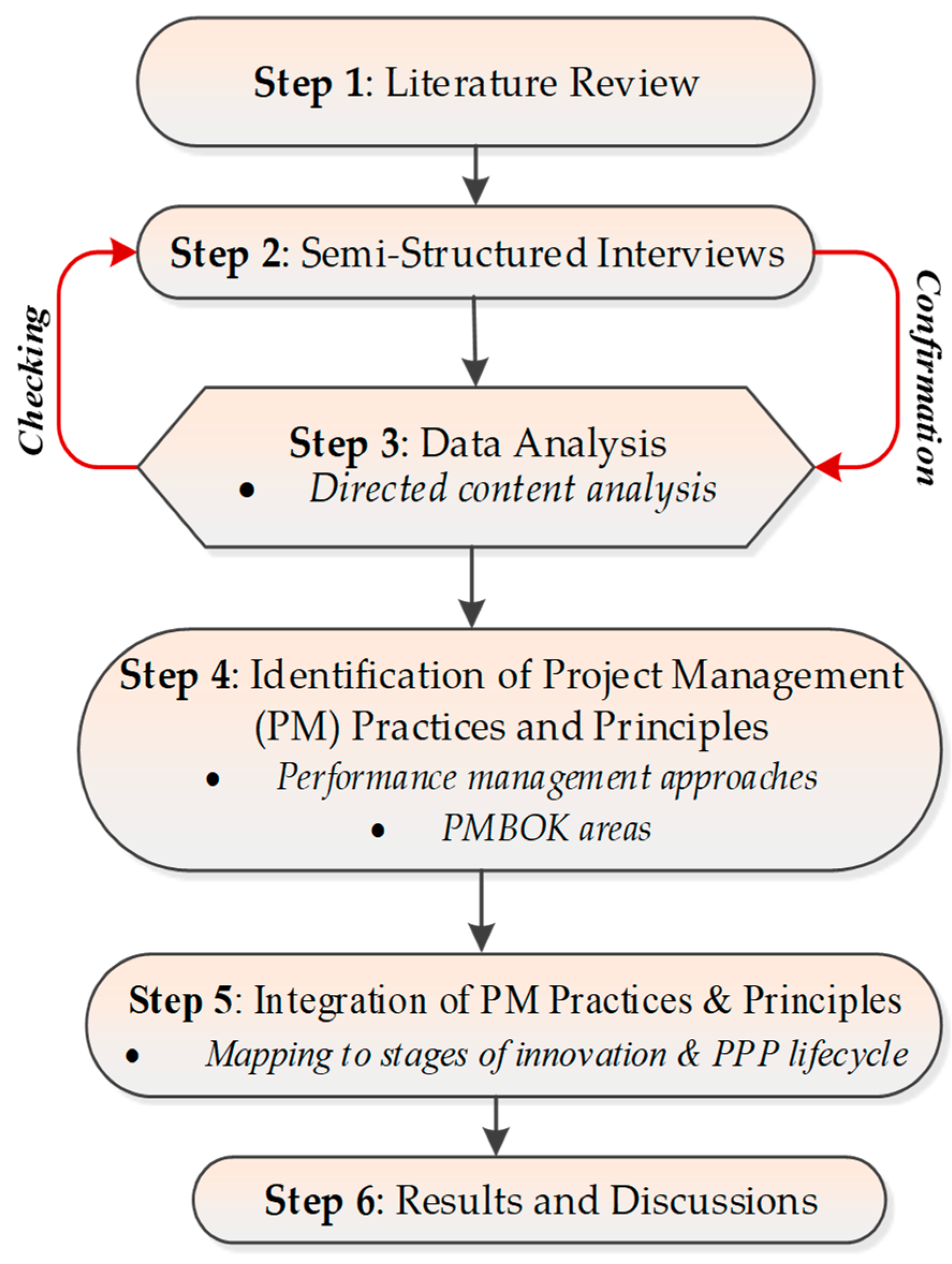

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Research Design

4.2 Selection of respondents

4.3. Interview Protocol

4.4. Data Collection, Confirmation Procedure, and Analysis

4.4.1. Individual Characteristics

4.4.2. Organisational Characteristics

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Project Management Practices and Principles for PPPs Implementation

5.2. Project Management Themes

5.2.1. Management and Monitoring of the PPP Projects

[…] being a private partner and Economist by profession, I did not have Construction project management skills. Therefore, I looked for a competent Engineer to visit and inspect the site on daily basis. […].(Interviewee D)

[…] I gave motivation to the structural site engineer to make him come and inspect the project frequently. After this he had to write a report on each stage which was filed for future reference in case of anything and this made him to be committed and true to the work inspected and report written by him […].

5.2.2. Performance Management

“Yes, by assessing the actual work done using time, cost and quality. But in case of poor performance it was very hard to rectify the situations and at the end some projects remained stalled or incomplete for a longer period”.

“Yes, by daily site visits and inspection by the Private partner engineer. But also, Government representatives inspected the works at some intervals (irregular)”.

By inspecting the works on daily basis and writing and filing reports which were [I] submitted to the project manager on monthly basis. Therefore, any technical failures or weaknesses were identified early enough.

5.2.3. Post Implementation and Operational Aspects

“[…] NHC had a share of 25% in most projects this being the value of the land while the partner had a share of 75%. The PPP contract lasts forever… There is a possibility of the private partner operating the property and pay NHC rent or each operating its own units within the property […]”

“Majority of properties are operated by private partners and then pay us our portion/share. This way it has helped we concentrate into other things”.

6. Conclusions

6.1. Limitations

6.2. Structured Framework for Future Studies

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abebe, F.K. Modelling Informal Settlement Growth in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Master’s Thesis, University of Twente, Enschede, The Netherlands, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- NHC. The National Housing Corporation Strategic Plan for 2010/11–2014/15; NHC: Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, 2010.

- Kidata, A. A Brief of Urbanization in Tanzania. Prime Minister’s Office Regional Administration and Local Government. In Proceedings of the Resilient Cities Conferences, Bonn, Germany, 1 June 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Sengupta, U. Government intervention and public–private partnerships in housing delivery in Kolkata. Habitat Int. 2006, 30, 448–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobuza, Y. Social Housing in South Africa: Are Public Private Partnerships (PPPs) a Solution; MBA Degree; University of Pretoria: Pretoria, South Africa, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Moskalyk, A. Public-private Partnerships in Housing and Urban Development; UN-HABITAT: Nairobi, Kenya, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Romero, M.J. What Lies Beneath? A critical Assessment of PPPs and Their Assessment of PPPs and Their Impact on Sustainable Development. European Network on Debt and Development (Eurodad), 2016. Available online: http://www.eurodad.org/whatliesbeneath (accessed on 4 March 2018).

- Trangkanont, S.; Charoenngam, C. Private partner’s risk response in PPP low-cost housing projects. Prop. Manag. 2014, 32, 67–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rwelamila, P.D.; Ogunlana, S. W107- Construction in Developing Countries Research Roadmap—Report for Construction. Report for the International Council for Research and Innovation in Building and Construction; CIB General Secretariat: Delft, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Verweij, S.; Teisman, G.R.; Gerrits, L.M. Implementing public-private partnerships: How management responses to events produces (un) satisfactory outcomes. Public Works Manag. Policy 2017, 22, 119–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavishe, N.; Jefferson, I.; Chileshe, N. An analysis of the delivery challenges influencing Public Private Partnership in housing projects: The case of Tanzania. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2018, 25, 202–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jefferies, M.; Gameson, R.; Rowlinson, S. Critical success factors of the BOOT procurement system: Reflections from the Stadium Australia case study. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2002, 9, 352–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, E.; Chan, A.P.C.; Kajewski, S. Factors contributing to successful public private partnership projects: Comparing Hong Kong with Australia and the United Kingdom. J. Facil. Manag. 2012, 10, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, S. Critical success factors of public private partnership (PPP) implementation in Malaysia. Asia-Pac. J. Bus. Admin. 2013, 5, 6–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. Tanzania Economic Update The Road Less Traveled Unleashing Public Private Partnerships in Tanzania, Africa Region Macroeconomics and Fiscal Management Global Practice. 2016. Available online: http://www.worldbank.org/tanianla/economlcupdate (accessed on 10 March 2018).

- URT. Prime Minister’s Office: National Public Private Partnership (PPP) Policy; Restricted Circulation: Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Jamali, D. Success and failure mechanisms of public private partnerships (PPPs) in developing countries: Insights from the Lebanese context. Int. J. Public Sect. Manag. 2004, 17, 414–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akintoye, A.; Kumaraswamy, M. Public Private Partnerships: CIB TG72 Research Roadmap Report for the International Council for Research and Innovation in Building and Construction; CIB General Secretariat: Delft, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Aundhe, M.D.; Narasimhan, R. Public private partnership (PPP) outcomes in e-government—A social capital explanation. Int. J. Public Sect. Manag. 2016, 29, 638–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, E. Diffusion of Innovations; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, E. Diffusion of preventive innovations. Addict. Behav. 2002, 27, 989–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, E. A prospective and retrospective look at the diffusion model. J. Health Commun. 2004, 9, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogers, E.M. Diffusion of Innovations, 5th ed.; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, E. Diffusion of Innovations; Free Press of Glencoe: New York, NY, USA, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Elison, S.; Ward, J.; Davies, G.; Moody, M. Implementation of computer-assisted therapy for substance misuse: A qualitative study of Breaking Free Online using Roger’s diffusion of innovation theory. Drugs Alcohol Today 2014, 14, 207–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, M.R.; Chileshe, N.; Zuo, J.; Baroudi, B. Adopting global virtual engineering teams in AEC Projects: A qualitative meta-analysis of innovation diffusion studies. Constr. Innov. 2015, 15, 151–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.-H. The antecedents of creative article diffusion on blogs: Integrating innovation diffusion theory and social network theory. Inf. Rev. 2017, 41, 70–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewett, T.; Whittier, N.C.; Williams, S.D. Internal diffusion: The conceptualizing innovation implementation. Compet. Rev. Int. Bus. J. 2007, 17, 8–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suprun, E.V.; Stewart, R.A. Construction innovation diffusion in the Russian Federation: Barriers, drivers and coping strategies. Constr. Innov. 2015, 15, 278–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obwegeser, N.; Müller, S.D. Innovation and public procurement: Terminology, concepts, and applications. Technovation 2018, 74–75, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, C.; Liu, Y.; Hope, A.; Wang, J. Review of studies on the public-private partnerships (PPP) for infrastructure projects. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2018, 36, 773–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel Aziz, A.M. Successful delivery of public-private partnerships for infrastructure development. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2007, 133, 918–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Project Management Institute (PMI). A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK Guide), 6th ed.; Project Management Institute: Newtown Square, PA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Abednego, M.P.; Ogunlana, S.O. Good project governance for proper risk allocation in public-private partnerships. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2006, 24, 622–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Tam, V.; Gan, L.; Ye, K.; Zhao, Z. Improving sustainability performance for public-private partnership (PPP) projects. Sustainability 2016, 8, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osei-Kyei, R.; Dansoh, A.; Ofori-Kuragu, J.K. Reasons for adopting Public-Private Partnership (PPP) for construction projects in Ghana. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 2014, 14, 227–238. [Google Scholar]

- Ameyaw, E.E.; Chan, A.P.C. Risk ranking and analysis in PPP water supply infrastructure projects: An international survey of industry experts. Facilities 2015, 33, 428–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavishe, N.; Jefferson., I.; Chileshe, N. Evaluating issues and outcomes associated with public–private partnership housing project delivery: Tanzanian practitioners’ preliminary observations. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavishe, N.; Chileshe, N. Critical success factors in public-private partnerships (PPPs) on affordable housing in Tanzania. J. Facil. Manag. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul-Aziz, A.R.; Kassim, P.S.J. Objectives, success and failure factors of housing public-private partnerships in Malaysia. Habitat Int. 2011, 35, 150–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babatunde, S.O.; Opawole, A.; Akinsiku, O.E. Critical success factors in public-private partnership (PPP) on infrastructure delivery in Nigeria. J. Facil. Manag. 2012, 10, 212–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Famakin, I.O.; Aje, I.O.; Ogunsemi, D.R. Assessment of success factors for joint venture construction projects in Nigeria. J. Financ. Manag. Prop. Constr. 2012, 17, 153–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwofie, T.E.; Afram, S.; Botchway, E. A critical success model for PPP public housing delivery in Ghana. Built Environ. Proj. Asset Manag. 2016, 6, 58–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. World Bank Group Support to Public-Private Partnerships: Lessons from Experience in Client Countries; fy02–1202–12; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2015; pp. 121–139. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, Z.A.; Thorton, N.; Frazer, M. Experience of a financial reforms project in Bangladesh. Public Admin. Dev. 2003, 20, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hueskes, M.; Verhoest, K.; Block, T. Governing public-private partnerships for sustainability—An analysis of procurement and governance practices of PPP in infrastructure projects. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2017, 35, 1184–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikwasi, G.J. Causes and Effects of Delays and Disruptions in Construction Projects in Tanzania. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference and Workshop on Built Environment in Developing Countries ‘Fragmented Futures: The Built Environment in a Volatile World’, Adelaide, Australia, 4–5 December 2012; pp. 138–148. [Google Scholar]

- South, A.; Eriksson, K.; Levitt, R. How infrastructure public-private partnership projects change over project development phases. Proj. Manag. J. 2018, 49, 62–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itika, J.; Mashindano, O.; Kessy, F.L. Successes and constraints for improving Public Private Parternship in health services delivery in Tanzania. Econ. Soc. Res. Found. (ESRF) 2011, 36, 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Kassanda, P. Public Private Partnerships in Tanzania: The new regime explained. Proj. Constr. 2013. Available online: http://www.clydeco.com/uploads/Files/Publications/2013/MEBE_-_010_-_Public_Private_Partnerships_in_Tanzania_the_new_regime_explained_-_Eng_-_Sep2013_2.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2018).

- Kavishe, N.; An, M. Challenges for Implementing Public Private Partnership in Housing Projects in Dar es Salaam City, Tanzania. In Proceedings of the 32nd Annual ARCOM Conference, Manchester, UK, 5–7 September 2016; Volume 2, pp. 931–940. [Google Scholar]

- Osei-Kyei, R.; Chan, A.P.C. Review of studies on the Critical Success Factors for Public-Private Partnership (PPP) projects from 1990 to 2013. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2015, 33, 1335–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavishe, N.; Chileshe, N. Joint venture housing projects in Dar es Salaam City: An analysis of the challenges and effectiveness. In Proceedings of the 33rd Annual ARCOM Conference, Cambridge, UK, 4–6 September 2017; Volume 2, pp. 144–153. [Google Scholar]

- Kavishe, N.; Chileshe, N. Driving forces for adopting in Tanzanian housing projects. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chileshe, N. Delivering Sustainability through Construction and Project Management: Principles, Tools and Practices. In Creating Sustainable Communities in a Changing World; Roetman, P., Daniels, C., Eds.; Crawford House Publishing: Goolwa, Australia, 2011; pp. 111–118. [Google Scholar]

- World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED). Our Common Future; University Press: Oxford, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Abidin, N.Z.; Pasquire, C.L. Delivering sustainability through value management: Concept and performance overview. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2005, 12, 168–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kivila, J.; Martinsuo, M.; Vuorinen, L. Sustainable project management through project control in infrastructure projects. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2017, 35, 1167–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chileshe, N.; Rameezdeen, R.; Hosseini, M.R. Drivers for adopting reverse logistics in the construction industry: A qualitative study. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2016, 23, 134–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axinn, W.G.; Pearce, L.D. Mixed Method Data Collection Strategies; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Denscombe, M. The Good Research Guide: For Small-Scale Social Research Projects; McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, T.; Wilkinson, S. Adopting innovative procurement techniques: Obstacles and drivers for adopting Public Private Partnerships in New Zealand. Constr. Innov. 2011, 11, 452–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, S.Q.; Dumay, J. The qualitative research interview. Qual. Res. Account. Manag. 2011, 8, 238–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, D.W.; Dressel, U.; Chevers, D.; Zeppetella, L. Agency theory perspective on public-private-partnerships: International development project. Int. J. Prod. Perform. Manag. 2018, 67, 239–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches; SAGE Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Almarri, K.; Abuhijleh, B. A qualitative study for developing a framework for implementing public-private partnerships in developing countries. J. Facil. Manag. 2017, 15, 170–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, M.Q. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods; Sage Publication: London, UK; Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Osei-Kyei, R.; Chan, A.P.C. Public sector’s perspective on implementing Public-Private Partnership (PPP) policy in Ghana and Hong Kong. J. Facil. Manag. 2018, 16, 175–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, G.A. Naturalistic inquiry and the saturation concept: A research note. Qual. Res. 2008, 8, 137–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, B.; Sim, J.; Kingstone, T.; Baker, S.; Waterfield, J.; Bartlam, B.; Burroughs, H.; Jinks, C. Saturation in qualitative research: Exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Qual. Quant. 2018, 52, 1893–1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burmeister, E.; Aitken, L.M. Sample size: How many is enough? Aust. Crit. Care 2012, 25, 271–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ardichvili, A.; Page, V.; Wentling, T. Motivation and barriers to participation in virtual knowledge sharing communities of practice. J. Knowl. Manag. 2003, 7, 64–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zawawi, M.I.Z.; Kulatunga, U.; Thayaparan, M. Malaysian experience with public-private partnership (PPP): Managing unsolicited proposal. Built Environ. Proj. Asset Manag. 2016, 6, 508–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.Y.; Shen, Q.P.; Cheng, E.W.L. A review of studies on Public-Private Partnership projects in the construction industry. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2010, 28, 683–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odoemena, A.T.; Horita, M. A strategic analysis of contract termination in public-private partnerships: Implications from cases in sub-Sahara Africa. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, N.; Ying, F. Method selection: A conceptual framework for public sector PPP selection. Built Environ. Proj. Asset Manag. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, H.R. Public Private Partnerships (PPPs): The Concept, Rationale and Evolution Stakeholders’ Perspective. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Public-Private Partnerships, Austin, TX, USA, 26–29 May 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bayiley, Y.T.; Teklu, G.K. Success factors and criteria in the management of international development projects: Evidence from projects funded by the European Union in Ethiopia. Int. J. Manag. Proj. Bus. 2016, 9, 562–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verweij, S. Producing satisfactory outcomes in the implementation phase of PPP infrastructure projects: A fuzzy set of qualitative comparative analysis of 27 road constructions in the Netherlands. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2015, 33, 1877–1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak, Y.H.; Chih, Y.Y.; Ibbs, C.W. Towards a comprehensive understanding of public-private partnerships for infrastructure development. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2009, 51, 51–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manu, P.; Mahamadu, A.-M.; Booth, C.; Olomolaiye, P.; Ibrahim, A.D.; Coker, A. Assessment of procurement capacity challenges inhibiting public infrastructure procurement: A Nigerian inquiry. Built Environ. Proj. Asset Manag. 2018, 8, 386–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ika, L.A.; Diallo, A.; Thuillier, D. Critical success factors for World Bank projects: An empirical investigation. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2012, 30, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalegama, S.; Chileshe, N.; Ma, T. Critical success factors for community—Driven development projects: A Sri Lankan community perspective. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2016, 34, 643–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rwelamila, P.D. Construction project performance in developing countries. In Contemporary Issues in Construction in Developing Countries; Spoon Press, Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 2012; pp. 318–346. [Google Scholar]

- Shokri-Ghasabeh, M.; Chileshe, N. Knowledge management: Barriers to capturing lessons learned from Australian construction contractor’s perspective. Constr. Innov. Inf. Process Manag. 2014, 14, 108–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarmento, J.M.; Renneboog, L. Anatomy of public-private partnerships: Their creation, financing and renegotiations. Int. J. Manag. Proj. Bus. 2016, 9, 94–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chileshe, N.; Kikwasi, G.J. Critical success factors for implementation of risk assessment and management practices within the Tanzanian construction industry. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2014, 21, 291–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chileshe, N.; Kikwasi, G.J. Risk assessment and management practices (RAMP) within the Tanzanian construction industry: Implementation barriers and advocated solutions. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 2014, 14, 239–254. [Google Scholar]

- Muller, R.; Klein, G. What constitutes a contemporary contribution to Project Management Journal? Manag. J. 2018, 49, 3–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whetten, D.A. What constitutes a theoretical contribution? Acad. Manag. 1989, 14, 490–495. [Google Scholar]

- Colquitt, J.A.; Zapata-Phelan, C.P. Trends in theory building and theory testing: A five-decade study of the academy of management journal. Acad. Manag. J. 2007, 50, 1281–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voordijk, H. Contemporary issues in construction in developing countries. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2012, 30, 331–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chileshe, N.; Hosseini, M.R.; Jepson, J. Critical barriers to implementing risk assessment and management practices (RAMP) in the Iranian construction sector. J. Constr. Dev. Countries 2016, 21, 81–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | Author | PPP Principles | Emergent Themes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | [32] | 1. Availability of PPP institutional/legal framework | Through thee examination of these eight principles, 3 themes emerged: (1) Enabling environment; (2) PPP skills and awareness; (3) Meeting output specifications. Both the ‘themes’ and ‘principles’ are comparable to CSFs identified in previous studies associated with challenges to PPPs [11] Such an approach increases their reliability and validity |

| 2. Availability of PPP policy and implementation units | |||

| 3. Perception of private finance objectives | |||

| 4. Perception of risk allocation and contractor’s compensation | |||

| 5. Perception of value-for-money | |||

| 6. PPP process transparency and disclosure | |||

| 7. Standardization of PPP procedures and contracts | |||

| 8. Performance specification and method specification | |||

| 2. | [6] | 1. The interest of the public is supreme | Likewise, in this et, the following 3 themes emerged: (1) Satisfying the need of the public; (2) Meeting output specification; and (3) Measuring project viability. These too are comparable to the challenges and benefits of PPPs as well as potential CSFs identified in previous studies to PPPs [11,32,33] |

| 2. Good practices must be maintained throughout the life of the project | |||

| 3. PPP project should be carefully planned and defined in scope, size and objectives | |||

| 4. Measuring the viability of the project against the criteria set by the initiating partner | |||

| 5. The PPP model selected should offer value for money (VfM) | |||

| 6. Competitive, transparent and fair tendering process | |||

| 7. For an urban sector PPP project, must mirror the needs of the community | |||

| 8. Adequate management of the project throughout the agreement period as stated in the contract |

| No | Theme | Typical Interview Questions | Stages of Adoption 1,* | PPP Project Life Cycle 2,3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Management and monitoring | How did you manage and monitor the PPP affordable housing schemes projects? | IU | Project implementation phase |

| 2 | Performance management | Did you carry out performance measurements? | IU | Project implementation phase |

| Probe: How did measure the performance? | ||||

| 3 | Post implementation and operational aspects | After building the project, how did you operate the project? | CU | Closing 4 |

| Interviewee | Designation of Respondents | Experience in Current Position | Education Level |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | Managing director | 11–15 years | Master’ degree |

| B | Senior Legal Officer | <5 years (4 years) | Master’ degree |

| C | Assistant Legal officer | <5 years (1 year) | Master’ degree |

| D | CEO | 11–15 years (12 years) | Master’ degree |

| E | Project manager | >5 years | Master’ degree |

| F | PPP Clerk of Works | >15 years | Master’ degree |

| G | Managing Director | >15 years | Ph.D. in Economics |

| H | Project Manager | >15 years | Master’ degree |

| I | Associate Professor | >15 years (20 years) | Ph.D. |

| J | Acting Director | 6–10 years | Master’ degree |

| Interviewee | Current Position 1 | Implementing PPPHP | Experience 2 (Years) | Type of PPP Contract 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Public partner | Yes | >10 | BOT and TURNKEY |

| B | Public partner | Yes | >10 | BOT and DB |

| C | Public partner | Yes | 1–2 | BOT and DB |

| D | Public partner | Yes | 1–2 | DB |

| E | Public partner | Yes | >10 | DB |

| F | Consultant | Yes | 1–2 | DB |

| G | Private Partner | Yes | 1–2 | DB |

| H | Public partner | Yes | >10 | BOT and DB |

| I | Teaching/Consultant | No | No * | N/A |

| J | PPP advisor | No | N/A | N/A |

| No. | Project Management Practices and Principles | Interviewees 1 | No 4 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A * | B * | C * | D | E * | F * | G | H * | I a | J a | |||

| 1 | Undertaking checks and balance from design to construction stage | √ | 1 | |||||||||

| 2 | Site meetings | √ | √ | √ | 3 | |||||||

| 3 | Official and unofficial site visits and inspections 2 | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | 5 | |||||

| 4 | Having a consultant manager to receive all PPP project reports | √ | √ | 2 | ||||||||

| 5 | Coordinated team (Quantity surveyors, architects, and engineers) to oversee the project | √ | 1 | |||||||||

| 6 | Some projects have public partner consultants to oversee and manage the project | √ | 1 | |||||||||

| 7 | NHC managing the project to a very lesser extent as majority left to private partner | √ | 1 | |||||||||

| 8 | Engagement of a competent engineer to visit and inspect the site on daily basis | √ | 1 | |||||||||

| 9 | Steering committee meeting every three months unless there is an emergency | √ | 1 | |||||||||

| 10 | Board meetings | √ | 1 | |||||||||

| 11 | Government representatives inspecting the works at some intervals (irregular) 3 | √ | 1 | |||||||||

| 12 | Assessing the actual work done against the schedule of works | √ | 1 | |||||||||

| 13 | Preparation of projects and submission to the PPP technical committee | √ | 1 | |||||||||

| 14 | Documenting the site inspections (Reports) | √ | √ | √ | √ | 4 | ||||||

| Total | 6 | 2 | 1 | 7 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 24 | |

| Performance Management Approach | Interviewees 1 | No | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A * | B * | C * | D | E * | F * | G | H * | I | J | ||

| Assessing the actual work done against the schedule of works | √ | √ | √ | √ | 4 | ||||||

| Assessing the actual work done using time, cost and quality | √ | 1 | |||||||||

| Daily inspection of works | √ | 1 | |||||||||

| Assessing the progress of the work by both partners | √ | 1 | |||||||||

| Total | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 7 |

| Interviewee Code | Response to Post Implementation and Operational Aspects |

|---|---|

| D | The private partner operates the whole project, but each partner receives his share after maintenance and operation costs have been deducted |

| E | Private partners have been operating the properties and pay us our percentage (%) share of the project |

| F | It is still on its early stages of construction hence it’s not measurable yet. |

| G | The whole project is managed by private partner and the National Housing Corporation (NHC) is paid its share on the agreed time frame |

| H | Private partners have been operating the projects |

| I * | - |

| J * | - |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kavishe, N.; Chileshe, N. Identifying Project Management Practices and Principles for Public–Private Partnerships in Housing Projects: The Case of Tanzania. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4609. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10124609

Kavishe N, Chileshe N. Identifying Project Management Practices and Principles for Public–Private Partnerships in Housing Projects: The Case of Tanzania. Sustainability. 2018; 10(12):4609. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10124609

Chicago/Turabian StyleKavishe, Neema, and Nicholas Chileshe. 2018. "Identifying Project Management Practices and Principles for Public–Private Partnerships in Housing Projects: The Case of Tanzania" Sustainability 10, no. 12: 4609. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10124609

APA StyleKavishe, N., & Chileshe, N. (2018). Identifying Project Management Practices and Principles for Public–Private Partnerships in Housing Projects: The Case of Tanzania. Sustainability, 10(12), 4609. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10124609