Abstract

This paper presents the development of a concept for a circular economy (CE) regional monitoring framework for European countries, an example that can be used by regional policymakers as a supportive instrument for faster and more effective implementation of the CE model of regional development. The work identifies appropriate focus areas and ‘pillars’ for such a framework, and proposes key aspects for evaluating CE-based regional development. The concept for the CE regional monitoring framework is divided into a basic (conceptual) level and an applied (practical) level in order to connect the concept of CE with its practical implementation, evaluation, and monitoring in a given region. The study also highlights the European context of the CE concept and its similarities and differences in relation to existing CE concepts around the world.

1. Introduction

According to the International Institute for Sustainable Development, the global economy currently totals an estimated US $80 trillion—double what it was at the beginning of the 21st century. At the same time, the world’s population is four times what it was in comparison with the beginning of the 20th century, and numerous forecasts show that another 50% increase—to about 11 billion people—could occur by the year 2100. These changes could be challenging for the current economic model based on ever growing production and consumption. Such a situation moves humanity steadily toward greater scarcity of, and unequal access to, natural resources and energy, as well as increasing environmental, social, and geopolitical concerns [1].

In response to these challenges, the circular economy (CE) concept has been explored as an alternative approach, a leaner economy concept than the prevailing “take-make-dispose” model [2,3]. Instead of using up natural resources and disposing of products when they are damaged or no longer needed, a circular economy is focused on creating more durable materials and retaining their worth in the value chain for as long as possible [1].

Recently a number of studies have been devoted to the ongoing debate surrounding definitions of the concept of a circular economy [4,5,6,7,8]. In the last few years, the concept has become increasingly popular not only within the academic community, but primarily among policymaking, advocacy, and consultancy representatives. Despite the popularity of the concept, CE does not have a commonly accepted definition among scientists and other professionals [4,9]. In a CE study from 2015, Murray A. et al. noted that “One interesting difference between CE and most of the other schools of sustainable thought is that it has largely emerged from legislation rather than from a group of academics who have split from one field and have started a new one. It could be an explanation of why the CE has not yet acquired a journal, editorial board, and group of faculties of its own, as these are the normal territorial markings of a group of academics” ([10], p. 373).

Since 2014, the EU has actively implemented the CE concept at various operational levels, but there has been no procedure to track its progress and monitor its implementation. Yet monitoring of actions planned and accomplished is one of the most important aspects of the transition to CE. It is therefore vital to develop an EU, national, regional, and local level monitoring framework in order to track the progress and effects of the EU’s transition towards CE. That is why one of the European Commission’s initiatives for 2017 was to prepare such a monitoring framework for assessing the progress of the circular economy at the national level across the EU Member States. It was claimed that such a monitoring framework would be based on existing EU Scoreboards for Resource Efficiency and for Raw Materials usage, and would include other meaningful indicators that measure the main elements of the circular economy. The framework was also supposed to be aligned with the monitoring of the Sustainable Development Goals program [11], as the CE idea is driven by the concept of sustainable development [12].

In December 2017 the European Commission finally released a CE monitoring framework intended to monitor the progress of CE implementation at the Member States’ level. There are four main monitoring areas: production and consumption, waste management, secondary raw materials, and innovations. The framework consists of 10 indicators, some of which are broken down into sub-indicators. The framework released could be described as basic; its monitoring areas are focused mainly on resources and materials issues at the EU Member States’ levels.

Such a framework may not be detailed enough for monitoring the effects of important CE areas like social innovations, eco-innovations, sharing economy initiatives, the level of greening of the main economic sectors, new business models’ implementation, eco-design, and architecture initiatives—all identified in the latest research on CE from a European perspective and which could also be important at regional and local levels [3,8,13]. For the time being, the European Commission’s monitoring actions were proposed only for the national level, with no proposals for the other operational levels of implementation. Thus, even when first steps towards CE monitoring at the national level are taken, the framework would not adequately capture CE effects at the local and regional levels. The region as an administrative unit is, however, vital in the context of European Union development policy.

A strong, regionally-focused orientation of development policy could be supported by the role of regions in redistributing European Union financial resources where European Structural and Investment Funds are regionally oriented (specifically the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) and the European Social Fund (ESF), the Cohesion Fund, the European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development (EAFRD), and the European Maritime and Fisheries Fund (EMFF)). EU regional policy addressing those funds constitutes the single largest share of the EU budget for 2014–2020 (€351.8 billion out of a total €1082 billion) and is therefore the Union’s main investment arm.

Financial resources accumulated in these funds are used for improving strategic transport and communications infrastructure. At the same time, they help to transition toward a more environmentally friendly economy, to support innovative and more competitive entrepreneurship, to create job opportunities, to adapt education systems to the modern labor market, and to eliminate social exclusion [14]. The main direction of such investment funds is highly supportive of the CE concept.

Moreover, one of the key tasks of the EU Cohesion Policy for 2014–2020 is making the circular economy a reality. In the policy’s new investment framework, significant funding (150 billion euros) was planned for waste management, CE related innovation, SME competitiveness, resource efficiency, and low-carbon investments [15].

Taking into account such an influential role of the regions in EU development policy and the allocation of substantial funds for transition to circular economy within regional development funding, the current study focuses on the regional level of CE implementation. This study is devoted to developing the concept of the CE regional monitoring framework in order to support regional policymakers in CE implementation via more effective monitoring actions.

There are a few more arguments supporting the importance of CE-oriented research specifically emphasizing European regions. Since announcing the program, “Towards a circular economy: A zero waste programme for Europe” [16], CE issues have started to be discussed more frequently at the regional and local levels. In 2016, some initiatives demonstrating the importance of CE implementation at those levels were, in fact, launched. One of them is the Urban Agenda for the EU (Pact of Amsterdam), an initiative that promotes the role of urban authorities in achieving better regulations, including circular economy aspects with a focus on waste management (turning waste into a resource), the “sharing economy”, and resource efficiency [17].

One more regional level CE support initiative is the Interreg V Europe program 2014–2020, which helps regional and local governments across Europe to develop and deliver better policies. Since it was launched, 26 approved projects address the topic of environment and resource efficiency. Twelve of these target resource efficiency and circular economy. This illustrates the growing interest of Europe’s regions in moving in this direction [18].

Circular economy has thus become a strategic approach for further EU growth and sustainable development not only at the national level among the EU Members, but also on local and regional scales. This suggests that a more thorough study is urgently needed which develops the concept of monitoring the effects of CE implementation within the European-specific context.

In order to reach this study’s goal of developing the concept of a CE regional monitoring framework, the following objectives were accomplished:

- identifying the European context of the CE concept and the areas of regional development focus that are potentially the most influenced by CE

- investigating the potential impact of the CE model on regional development

- developing the concept for a CE regional monitoring framework based on identification of the main focus areas and pillars of CE-based regional development

- proposing key aspects for evaluating CE-based regional development within the proposed CE focus areas

These aspects of analysis are important because a priority for effective public sector management of CE transition is quality assurance. According to scientists researching public sector performance measurement, such quality assurance includes: prioritizing, indicator selection, data collection, analysis, and reporting [19]. The current research was focused on the ‘prioritizing’ aspect. This was an opportunity to establish the main priorities for effective CE regional monitoring as well as to investigate the potential impact of CE on regional development. Moreover, evaluation of the potential impact of the CE model on regional development has a role to play in further steps of quality assurance—‘analysis’ and ‘reporting’.

2. Materials and Methods

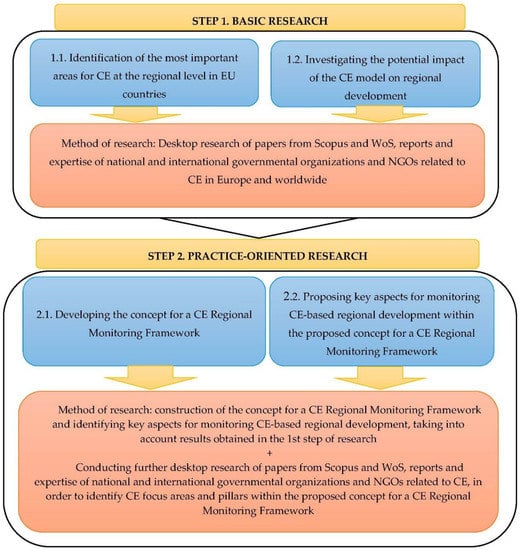

In order to develop the concept for a CE regional monitoring framework for European countries, research was designed according to the scheme presented in Figure 1. The two main divisions of the research, divided into Steps 1 and 2, are outlined.

Figure 1.

Research design for developing the concept of the CE regional monitoring framework for European Regions.

A review of academic literature, policy documents, reports, and expertise of national and international governmental organizations and NGOs related to CE was undertaken to comprehensively examine CE theory and its practical implementation. The aim of this approach was to analyze recent world trends in CE, identifying potential impacts of CE on regional development, and to propose the most important focus areas and pillars that should be monitored by regional policymakers in order to track the progress and measure the effects of the CE model of development.

The literature review consisted of the following main steps:

- (1)

- The first step of the review was comprised of desktop research of papers devoted to CE which were indexed in Scopus and WoS. The search option was used to find such key words as “circular economy”, “circular economy monitoring”, “circular economy in regions”, and “circular economy indicators”. This process identified the current trends in CE research studies, including existing definitions as well as the potential and limitations that scientists see for CE’s basic (theoretical) and applied (practical) levels.

- (2)

- The second step of the review was focused on reports and expertise of national and international governmental organizations and NGOs related to CE in Europe and worldwide. This step analyzed the understanding and approaches to implementation of CE issues at municipal, national, and even international levels. This was necessary because the earlier review of academic literature related to CE showed that there was no common understanding of the CE concept. Moreover, the understanding of the CE concept differs based on the environment and development priorities of the particular areas of implementation.

Section 3 of the paper presents the main results of the research. Section 3.1 provides a review of existing literature studying the CE concept’s development in the world’s largest national economies, as well as how the CE concept emerged and continues to develop in Europe. Importantly, this helped to identify the specific character of CE in Europe, one of the key competencies needed for preparing the next steps of the research. Section 3.2 and Section 3.3 were devoted to examining interrelations between the relatively well-known concept of regional development (RD) and CE as a new model for such development. At this stage of the research, it was possible to define the focus areas of CE in relation to RD, as well as to investigate the potential impact of CE on regional development. Section 3.4 presents the main findings of the research—the concept developed by the author for a CE regional monitoring framework, and the proposed main aspects for evaluating CE effects within the framework. Section 4 draws conclusions, highlighting certain limitations and further directions for research.

3. Results

3.1. Modern European and Worldwide Context of the CE Concept

The concept of CE is not new, having been introduced for the first time more than 50 years ago. The term “closed economy” was initially used in 1966 [20]. Being a multidisciplinary field, it contained elements from various branches of research that are the predecessors of the current concept.

The authors of recent studies, however, do not always agree with the earlier notion that CE should be based on closed loops, observing that “the economy of nature is based on an open system, not a closed system, that nature operates using short cycles, not extended lifetimes, that nature is sub-optimal, not optimal, and that nature is eco-inefficient, not eco-efficient” ([21], p. 479).

From the very beginning, the circular economy concept was focused mostly on resource efficiency, energy efficiency, and waste management approaches. That is why it appeared in national, regional, and local policies as an answer to large-scale environmental challenges, resource inefficiency and scarcity, air pollution, and so on. Such an approach was represented by the first global initiatives aimed at CE implementation in the resource and environmental policies of Germany, Japan, and the Netherlands [3,22,23,24] which also inspired Chinese policymakers to develop a national strategy since 2009 with its Circular Economy Promotion Law, and in the 11th, 12th, and 13th “Five-Year Plans” in China. It is widely acknowledged that China’s economic miracle has been achieved at the expense of its natural capital and environment. In order to deal with this problem, the CE approach has been chosen as a national policy for sustainable development of the country going forward [25]. Nevertheless, there remains a significant gap in CE development between China’s poorer western and richer eastern regions [25,26,27].

European Union experience with the CE model of development started in 2008 with Directive 2008/98/EC on waste [28], and further in the Europe 2020 Strategy for Smart, Sustainable, and Inclusive Growth for 2014–2020 [29]. Since then, a new era for circular economy development can be observed. The European CE concept has become broader and more complex. A major contribution to CE development was made by the UK-based Ellen MacArthur Foundation (EMF). The foundation, in cooperation with McKinsey & Company, prepared three reports on the concept [2,30,31] examining the potential of CE for the EU countries.

According to the foundation’s findings, adopting CE principles in Europe can substantially accelerate technological innovation creating a net benefit of €1.8 trillion by 2030, or €0.9 trillion more than on the current linear development path. Such changes would also bring about a projected increase of €3000 in household income, a reduction in the cost of time lost to congestion by 16%, and a halving of carbon dioxide emissions compared with current levels due to the decoupling effect [32].

Since 2012 the Foundation, with its partners (McKinsey & Company, SYSTEMIQ, SUN, ClimateWorks, and UNCTAD), has been actively engaged in the field of practical CE implementation while continuing research devoted to different aspects of CE, including priority sectors for CE implementation, plastic economy, the most important investment opportunities, and policy reforms and business actions needed to unlock CE potential [33,34,35]. The Ellen MacArthur Foundation recently presented research exploring CE opportunities in India [36] and China [37].

The foundation’s conceptual and practical proposals for CE in Europe were positively received by the European Commission. The founder of the EMF—Dame Ellen MacArthur—actively participates in shaping EU resource policy as a member of the European Commission’s Resource Efficiency Platform [38]. At the same time, the findings of the EMF report “Growth within: a circular economy vision for a competitive Europe” [32] were considered by the European Commission during work on the EU circular economy Action Plan (presented by the Commission at the end of 2015) [39,40]. Thus, the CE Action Plan’s general areas (product design, production process, consumption, waste management and secondary raw materials issues, innovation, and investments) and specific materials and sectors (plastic, food value chain, critical raw materials, construction and demolition, biomass, and bio-based products) to a high degree overlap with the areas of research activities carried out by the EMF since 2012.

In addition, EMF representatives also interact regularly with various European Commission bodies (DG Environment, DG Internal Market, Industry, Entrepreneurship and SMEs, DG Regional and Urban Policy, and DG Research and Innovation) and international institutions such as the OECD and the UN in order to boost CE implementation not only within the European community, but also at the international level. As a result of such fruitful cooperation, findings from EMF reports on CE provided sources of information for numerous strategies and studies commissioned by EC executive bodies [41,42,43].

CE-related actions have been taken not only at the EU level, but also at the national and regional government levels within EU countries. For the time being, such initiatives have consisted of the following: A circular economy in the Netherlands by 2050 [44]; Finland’s National Circular Economy Roadmap (Sitra, 2016) [45]; ProgRess II—German Resource Efficiency Programme (Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation, Building and Nuclear Safety, 2016) [46]; Leading the transition: a circular economy action plan for Portugal (Ministry of Environment, 2017) [47]; Towards a Model of Circular Economy for Italy—Overview and Strategic Framework (Ministry for the Environment, Land and Sea Ministry of Economic Development, 2017) [48]; France Unveils Circular Economy Roadmap (The French Ministry of Ecological and Solidarity Transition, 2018) [49]; and Roadmap towards the Circular Economy in Slovenia (Circular Change and other consortia of partners, 2018) [50]. At the regional and local levels, one can see initiatives such as Catalonia’s Promoting Green and Circular Economy in Catalonia: Strategy of the Government of Catalonia (Government of Catalonia, 2015) [51]; the Brussels Region’s Programme Régional en Economie Circulaire (2016) [52]; Scotland’s Making Things Last: A Circular Economy Strategy for Scotland [53]; Amsterdam’s Circular Amsterdam (City government of Amsterdam, 2016) [54]; Paris’ White Paper on the Circular Economy of Greater Paris (City government of Paris, 2016) [55]; Extremadura’s Extremadura 2030: Strategy for a Green and Circular Economy (Regional Government of Extremadura, 2017) [56]; London’s Circular Economy Route Map (London Waste and Recycling Board, 2017) [57]; and Flanders’ Circular Flanders kick-off statement (Vlaanderen Circulair, 2017) [58].

European research and actions supporting CE have brought about completely new directions. Comparative analysis of CE policy in China and Europe presented in [3] has shown that they “…have different focuses framed by different problems. China is more concerned with general environmental problems and pollution, while Europe is specifically focused on materials, resource efficiency, waste, new business models, new jobs, eco-innovations, social innovations, etc.” CE in Europe is based on the use of services and intelligent digital solutions, and on the design and production of more durable, repairable, reusable, and recyclable products, so that waste is treated as a valuable source of secondary raw materials and so that products are not owned by end users, but rather shared, leased, or rented [1]. Hence, modern CE for Europe is not only about resources, energy, waste, and air and soil pollution; it also considers the following:

- New ways of living and thinking

- New types of supplier and consumer relationships and connections

- New types of owning and usage

- New systems of taxation and income generation

- New approaches in production and consumption

- New approaches in design and construction

- New understanding of value-added creation

- New indicators of economic growth and development

- New meanings of national, regional, and local prosperity

- New approaches in strategic planning and development

All these changes began inter alia due to the introduction and integration of smart solutions and interference of the Internet of Things in all spheres of life at all operational levels [59,60]. Moreover, due to the complexity of the idea, CE became an umbrella covering strategies and practical solutions for economic system transformation at micro and macro levels. CE is observed as a concept that presents “new and unprecedented opportunities to create wealth and support well-being, as well as… the essential engine for achieving the ambitious UN Agenda 2030 and Sustainable Development Goals” (IISD, 2017) ([1], p. 1).

Even the European CE Action Plan could be used to support the argument that European CE is not limited to waste management issues, but should be treated as a broad sustainable development strategy covering a wide spectrum of issues specified in the plan, such as eco-design, support of e-commerce (online sales), elimination of false green sales and introduction of standardized ecolabeling, introduction of green public procurement, promotion of safe and cost-effective water reuse, support of biomass and bio-based materials, strong support for Member States and regions in strengthening CE-related innovation through smart specialization, etc. [39].

As soon as the importance of the circular economy model for EU countries was announced as a new strategic direction for development, a larger number of national, regional, and local initiatives were pushed into action with the purpose of transforming the previously used, leaner economy model into the circular economy approach [5,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,61].

“Towards a circular economy: A zero waste programme for Europe” [16] and “Closing the loop—An EU action plan for the Circular Economy” [39] are the main EU framework documents introducing and supporting the European CE model. In January 2017, the first report on year one CE implementation actions was released. According to the report, the following actions were accomplished on the EU level during 2016 [11]:

- Adopted eco-design working plan for 2016–2019

- Included guidance on circular economy in the Best Available Techniques reference documents (BREFs) for several industrial sectors

- Established CE criteria were integrated into the Green Public Procurement procedure (for buildings, roads, computers and monitors)

- Adopted an initiative on waste to energy

- Introduced waste shipment regulations

- Presented guidance on the integration of water reuse in water planning and management

- Completed sectoral-related actions on food waste, contracting and demolition, biomass, and bio-based materials

- Undertook innovation and investment actions related to CE (Innovation Deals pilot project; Establishment of a circular economy finance support platform; Horizon 2020 call for proposals: “Industry 2020 in the circular economy”, a €650 million investment in 2016 and 2017)

For 2017 the European Commission continued to implement the CE Action Plan and to work on a strategy for plastics in the CE, assessing options for the improvement of interface among chemicals, products, and waste legislation, as well as legislative proposals on water reuse and the CE monitoring framework for EU countries by the European Commission. As noted above, such a monitoring framework was not presented at the beginning of the CE Action Plan’s realization but was instead presented at the end of 2017 for the Member States’ level, and lacking assumptions for regional monitoring of the CE model of development. At the very beginning, the Commission only established targets for waste and recycling, while this is unlikely to be enough for such a complex and interdisciplinary field as CE. In April 2017 the Roadmap for Development of a Monitoring Framework for the Circular Economy was released. The document outlined the main trends in CE which must be taken into account. It also included information regarding what the initiative aims to achieve and how.

The current lack of CE monitoring instruments for European regions creates barriers to CE policy’s effective implementation, potentially slowing the realization of processes and strategies directed toward CE. The review of recent research on the modern concept of CE has shown that monitoring instruments should consider the differences in CE’s main objectives and specific factors in the EU’s various regions [62]. The current research results are intended to create added value by increasing CE monitoring’s effectiveness, and to be a supportive instrument for policymakers at different operational levels. As the research was focused on regional level monitoring, the specifics of CE in Europe discussed in the present chapter were taken into account in the development of the concept for a CE Regional Monitoring Framework.

3.2. Focus Areas for CE-Based Regional Development

For the effective regional monitoring of CE, one of the most important research tasks was identification of regional development areas that may be most influenced by the transition to CE, including potential benefits that CE will bring to regional development as well as challenges stemming from the shift from the leaner to the circular model. Such benefits and challenges look differently to the various stakeholder groups responsible for introduction of this new model in practice. Tasks, actions, and roles vary among local and regional authorities, business and finance sector representatives, academia, the R&D sector, and civil society and citizens. The CE regional monitoring framework was developed under the assumption that such a framework would be used in regional strategic planning and management processes.

In order to identify focus areas for monitoring within the CE regional monitoring framework, a review was conducted of recent regional studies on the CE model worldwide. Numerous region-specific studies on the CE model have been carried out for Chinese regions [26,27,63,64,65], but as was already noted, European and Chinese approaches differ. There are conceptual differences in policy activities.

Two key divergences are observed—priorities across the value chain and treatment of the spatial dimension of the CE. If waste and resources are important for both Europe and China, consumption patterns and product design appear as factors only in the EU’s policies. The Europeans are actively working on eco-design, durability, and consumption-oriented measures. As for the spatial dimension of the CE, EU regulations are almost entirely silent on issues of spatial management, whereas Chinese CE policy includes ambitions to integrate CE principles into land-use planning, paying special attention to environmentally sensitive spatial integration of residential, agricultural, and industrial activities [3]. From the very beginning, Chinese CE policy was strongly focused on the creation of CE areas in provinces, cities, and such zones as industrial parks [25].

Such differences in CE focus in China and European counties could be also explained by the fact that eco-design, durability, consumption-oriented measures, and sustainable production and consumption actually give a competitive advantage to European countries over their developing Asian counterparts, and could be treated as European core competencies. As the EU Member States are often unable to compete with developing countries in terms of cost, they should try to maintain a competitive advantage related to higher quality, durability, and utility of products and services for end-consumers and end-users. In such a situation, CE with a focus on innovations, smart solutions, and new business models is the main opportunity for Europe to retain this superiority.

Due to the mentioned differences in approaches to CE, measures of progress in China and Europe have different assumptions and focuses, but such differences provide an opportunity for both of these leading world macro regions to learn from each other’s experiences and to adopt a wider view of CE issues and their monitoring frameworks. CE monitoring has existed in China since 2009, but it should be noted that areas (groups) of monitoring are represented by resource output and consumption rate, integrated resource utilization rate, waste disposal, and pollutant emissions [25]. Such a system of monitoring has been seriously criticized due to the lack of social indicators, absolute emissions reduction indicators, absolute material and energy reduction indicators, and prevention-oriented indicators [3,25,66,67].

Although Chinese monitoring is criticized, it is useful in tracking progress at the macro, meso, and micro levels. As for Europe, the main problem is that a monitoring framework proposed only for the national level makes regional monitoring difficult, since the regional level’s main areas remain unidentified and key indicators do not exist.

The current study was focused on the CE model as a new concept for regional development within Europe at the NUTS 2 level. The NUTS (Nomenclature of Territorial Unit of Statistics) classification provides an objective basis for the allocation of EU structural funds. Such classification is used to define regional boundaries and to determine geographic eligibility for structural and investment funds. According to NUTS 2, regions were ranked and split into three groups: less developed regions (where GDP per inhabitant was less than 75% of the EU-27 average); transition regions (where GDP per inhabitant was between 75% and 90% of the EU-27 average); and more developed regions (where GDP per inhabitant was more than 90% of the EU-27 average) [68].

In identifying areas of regional development most influenced by the CE model’s implementation, it was reasonable to consider concepts and theories that examine regional development from the sustainable development point of view [69,70,71] because, as was pointed out earlier, CE is a sustainable development-driven concept. Moreover, according to the European Commission’s assumptions, activities related to circular economy tie in closely with key EU policy priorities and with global efforts on sustainable development [12].

Sustainable regional development became mainstream at the end of the 20th century [72]. Its popularity has increased as it focuses, inter alia, on solving environmental problems of existing patterns of resource use, fighting social inequalities, and at the same time looking for opportunities for economic growth. Regional development based on the sustainability concept therefore helps regions to develop in economic, social, and environmental terms [73].

As CE is directly related to the sustainable development concept and as it was defined by the International Institute of Sustainable Development, CE is essential for achieving the UN Sustainable Goals for 2030 [1,74]. Other researchers have defined CE as “…a new way of thinking about the future and how we organize ourselves, our economies, and societies. It is a positive and restorative approach that goes ‘beyond sustainability’: rather than minimizing the harm we do to natural ecosystems, we can seek to do them good” ([75], p. 246).

The European Commission sees the transition to a more circular economy “…as a supportive instrument for the EU’s efforts to develop a sustainable, low carbon, resource efficient, and competitive economy, and as an opportunity to transform our economy and generate new and sustainable competitive advantages for Europe.” [39].

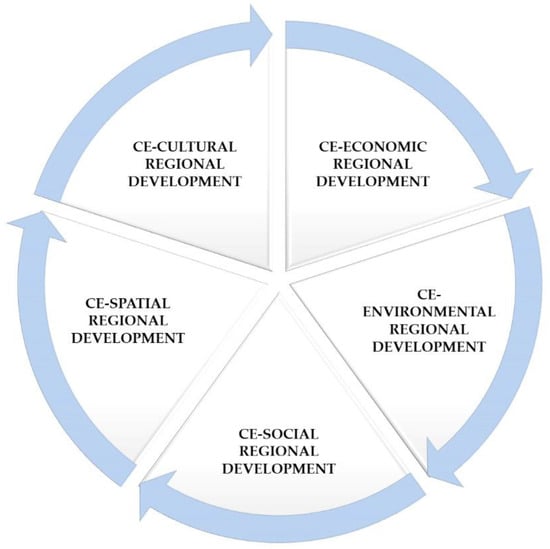

Such an approach to CE by the academic world and policymakers both in Europe and worldwide has prompted this author to base focus areas for CE monitoring on regional sustainable development. The current research therefore proposes a so-called CE-based regional development approach in the monitoring process. As this approach is an extension of sustainable regional development, its core elements—economic development, environmental restoration, and social wellbeing—were factored into the development of the concept for the CE regional monitoring framework. In addition to core sustainability aspects, to better reflect the modern CE concept and its possible influence on regional development, two more areas important for the CE model’s implementation were added, based on the findings of the research presented in Section 3:

- (1)

- Spatial regional development as an area that was already developed in the Chinese CE model of development, an area of potentially significant importance for the European model due to the integration of CE assumptions into land-use planning, which could stimulate such CE-related instruments as industrial and urban symbiosis [3,76,77,78]. Paying attention to the spatial area of CE-based regional development could also bring such advantages as integration of CE ideas into public transport infrastructure and public space organization.

- (2)

- The cultural regional development area which, from one perspective, could be interlinked with social development because CE, as a new way of thinking and behaving, is influential for new values and consumption patterns in society. From another perspective, the CE concept also causes changes in architecture and design and creates new forms of art inspired by CE thinking [79,80,81]. Cultural CE-based regional development is thus an additional focus area examined for the CE regional monitoring framework.

Cultural regional development was added here as a separate branch of CE-based regional development because, despite the appearance of numerous recent studies on the CE concept [4,6,7,8,10], it has also been observed that “…the values, societal structures, cultures, underlying world-views and the paradigmatic potential of CE remain largely unexplored” ([6], p. 544). It has also been argued that the cultural-cognitive aspect is a separate pillar of CE [13].

In their study, Ranta et al. [13] highlighted that norms and cultural aspects play an important role in shaping the transition towards more sustainable choices and adoption of CE principles. At the same time, they noticed that existing CE research is more focused on technical issues and technology, and less on social and cultural aspects. Thus, their study on CE issues took into account regional specifics in cultural-cognitive institutional drivers and barriers impacting the adoption of CE, and presented case studies for China, the US, and Europe.

Still, Ranta et al. were more focused on institutional aspects of the cultural issue and did not investigate how CE adoption influences the creation of new, and the development of existing, forms of art and urban design, which are also an important part of local cultures. As this specific part of regional development has not been adequately discussed to date, the current study has examined its potential positive impact on regional development. Moreover, this study proposes evaluation aspects of CE-based cultural regional development in order to monitor this little explored area.

As a result of such analysis, conclusions can be drawn regarding regional development areas that are potentially the most influenced by CE. The areas thus selected appear in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Focus areas for CE-based regional development.

The presented focus areas for CE-based regional development cover the mainstream directions of CE in Europe and elsewhere. Due to the complexity of this approach, the CE regional monitoring framework focus areas proposed in the study include a wide spectrum of processes influenced by transition to the CE model of development. One more crucially important research task before proposing the general concept for the CE regional monitoring framework was identification of the potential impacts, positive and negative, that the CE model could have at the regional level—something that will be addressed in the next chapter of the paper.

3.3. Potential Impact of CE on Regional Development

An examination of the potential impacts of the CE model was helpful in order to better investigate the identified CE focus areas for developing the concept of the framework. The CE model, as a basis for regional development, could have positive or negative effects as with any transition process. Exploration of positive impacts (potential benefits and opportunities) is particularly useful at the regional level for assessing whether or not the CE-based actions helped to achieve particular CE related benefits. These positive impacts of CE-based regional development are presented in Table 1 and based on the review of existing CE-related literature (academic papers, reports, and expertise of national and international governmental organizations and NGOs).

Table 1.

Potential positive impacts (benefits and opportunities) of CE-based regional development.

Although the above-mapped benefits of the circular economy indicate potentially positive influences on regional development, the European Environmental Agency Report on Circular Economy suggests the need for further evaluation: “Some aspects of current policy development, particularly in terms of wastes and new business model practices in several sectors, are moving tentatively towards circularity, but not necessarily in a systematic and coordinated way. More information is needed to inform decision makers and combine thinking about environmental, social, and economic impact.” ([82], p. 6).

As suggested earlier, CE—as in any transition causing substantial changes in regional development—could have not only positive but also some negative effects, barriers and challenges including negative impacts from the CE model for some stakeholders in a region. Prominent examples of areas facing transitional costs are industries producing virgin materials or low-quality consumer goods. The CE transition could have not only economic costs, but also social costs due to changes in employment rates in industries that find themselves in competition with CE-based alternatives. In this situation, policymakers have serious and broad responsibilities for preparing thoroughly-considered CE-related policies that balance the numerous benefits of the CE model with the need to reduce transitional costs as much as possible [82].

There are a few studies presenting barriers related to CE implementation in China [63,67,91]. Similar barriers to those presented in these studies can be observed in European countries, although barriers to CE in European regions are generally more region-specific, once again differing from Chinese circumstances. Studies on CE barriers identified four main groups of barriers:

- informational barriers and lack of CE awareness among various stakeholder groups—the general public, business sector, policymakers, NGO members, etc. [92,93,94,95,96,97,98]

- economic/financial/market barriers related to a lack of financial support for activities related to circular economy transition [84,98,99,100]

- institutional/regulatory/policy barriers [13,84]

- technical/technological barriers [84,100]

Additional studies devoted to the difficulties facing CE implementation [101,102,103] also emphasized the above-mentioned barriers as the main limitations. In [101], surveys and results of interviews with CE experts (businesses and policymakers) were presented, the main findings of which show that cultural barriers (a lack of consumer interest and awareness as well as hesitant business culture) are of primary significance. Those experts also singled out market barriers, specifying a lack of synergistic governmental interventions to accelerate the transition towards a circular economy. Notably, experts were in agreement that not a single technological barrier ranked among the most pressing CE deterrents.

One more valuable study on CE limitations and barriers was prepared by the Technopolis group and its partners (Fraunhofer ISI, Thinkstep, and Wuppertal Institute) and presented in the report “Regulatory Barriers for the Circular Economy”, which provided case studies identifying CE barriers related to contradictions in EU directives, legislation, and regulations [104].

The identified groups of barriers could be related to each CE focus area, as a majority of them have a horizontal character, meaning they could have an impact on economic, environmental, social, spatial, and even cultural aspects of the CE-based model of regional development.

It is also important to note that, while the CE model recently became a new strategy of development for both developing and developed countries, serious differences in its implementation can be observed between these two categories [105,106]. As recent research has also shown, the CE model differs in every European city and region depending on geographic, environmental, economic, and social factors [62]. That is why it is recommended for each region to identify not only the broader positive and negative impacts (benefits and opportunities, challenges, and barriers) presented above, but also to look for its own, region-specific processes that the CE model affects. A combination of identification of general impact and region-specific impact approaches in studying potential consequences of CE-based regional development seems to be the most effective for CE-based regional development policymaking.

3.4. CE Regional Monitoring Framework

3.4.1. Concept for CE Regional Monitoring Framework

The concept for a CE regional monitoring framework prepared within the current study was addressed mainly to regional policymakers to play a supporting role as a driving mechanism for CE-based regional development. It is based on focus areas described in Section 4. It is important to note that in EU countries, CE issues are at very different stages of implementation. Some countries are at advanced stages in the process like Germany, the Netherlands, Finland, Denmark, Sweden, and Spain, which already have national plans and strategies for CE [105]. At the same time, eastern European Union countries like Poland and the Czech Republic have made only initial steps in CE implementation, not necessarily considering CE-based regional development [106]. The concept for the presented Framework is therefore essential for forming a coherent approach to monitoring CE progress and identifying differences in advancement levels for individual regions, as well as building more efficient CE-based regional development strategies.

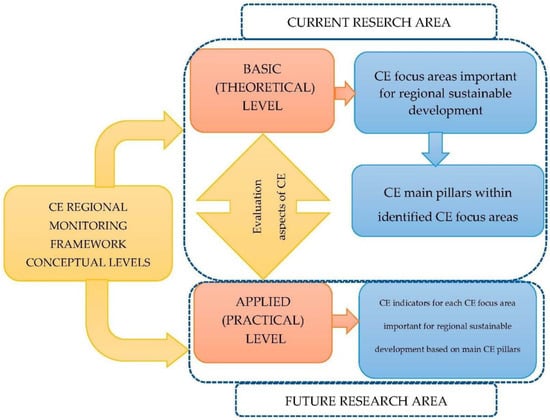

It is proposed here to distinguish two levels for developing the concept for the CE regional monitoring framework (Figure 3):

Figure 3.

CE regional monitoring framework conceptual levels.

- (1)

- Basic (conceptual) level which includes general CE areas and pillars of CE-based regional development

- (2)

- Applied (practical) level which includes monitoring indicators for measuring the progress and investigating effects in each core CE area important for regional development

The current study was focused on the basic (conceptual) level of the Framework, identifying the main pillars for each focus area of circular economy within the European context, and considering evaluation aspects for tracking progress in those areas.

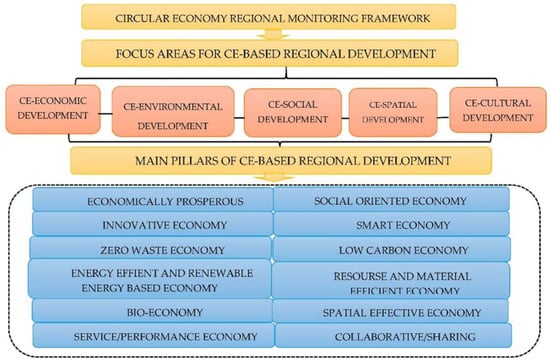

As noted, the CE concepts in Europe are diverse in scope, targeting not only primary and secondary resource efficiency, but also a wide spectrum of issues such as innovation, new business models, new patterns of consumption, active implementation of smart solutions, eco-design, green-jobs, etc. Given the interdisciplinary character of the various aspects of regional development, the pillars proposed were based on the earlier examined research, reports, and expertise on CE. The main criterion for choosing the pillars was a high level of potential influence on the above-proposed CE-based focus areas important for regional development.

The majority of the pillars are related to more than one focus area, so monitoring based on such pillars can be expected to result in a high degree of synergy from their mutual development. The pillars proposed are presented in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

CE regional monitoring framework focus areas and pillars.

As mentioned in the Introduction and Section 3.1 and Section 3.2, the CE concept at the European level refers to multiple mainstreams and trade-offs which sometimes cause inconsistences and contradictions in existing CE approaches between the conceptual and practical level. Multiple approaches to CE implementation can be seen at the level of EU Member States and regions. Figure 4 presents CE pillars based on the approaches developed in recent studies on CE indicated in Table 2. The complex character of European CE could certainly lead to complications for understanding and monitoring the transition process at the many levels involved. Such complexity could also provoke conflicts of interest among actors implementing different aspects of CE-based regional development. These factors reiterate the necessity that the stakeholders involved in CE implementation attempt to arrive at a common vision for CE in Europe.

Table 2.

Pillars proposed for monitoring CE effects within the CE regional monitoring framework

The results of a review of past research supporting the choice of the main pillars are presented in Table 2.

The pillars proposed in Table 2 address a wide spectrum of issues related to the European CE concept, within which numerous sub-concepts intersect to support CE implementation across the national, regional, and municipal levels. Depending on the given operational level, any of these pillars could be associated with CE-based development, but regional stakeholders would need to adapt implementation of the pillars to specific regional development needs. This tool provides one standard CE model which could be used as a common starting point for all EU regions. The main task for a regional stakeholder would be to concentrate on such focuses as are optimal for development in their particular region.

At the same time, monitoring CE progress in the region can, with a common framework, be based on standardized and comparable criteria. The proposed CE regional monitoring framework would thus support the broader tracking of progress on CE implementation even though different regions might have differing specific priorities for development.

Some of these pillars—such as innovative economy, low carbon economy, resource and energy efficient economy, zero waste—have been known for many years and were even included in “Europe 2020: A strategy for smart, sustainable, and inclusive growth” [29]. Moreover, there have already been such initiatives as the Innovation Union and Energy Union.

At the same time, pillars like the sharing/collaborative economy and service/performance economy have not previously been thoroughly researched but have become popular in recent years. These pillars sometimes have fewer supportive instruments at the national, regional, and local levels. CE actions taken at the EU level, on the other hand, have aided developments in these pillars; recently they have been actively discussed by scholars from all over the world, accelerating their implementation and making it possible to observe their direct interrelations with the CE model [121]. Additionally, the smart economy pillar links all the previously mentioned pillars and is one of the core instruments making CE a reality.

The smart economy pillar contributes to optimal planning and execution of urban development. Smart solutions, which are at the core of Smart Economy, are based on information and communications technology (ICT). Such technologies shape socio-cultural and politico-institutional structures, so the success and expansion of smart, sustainable solutions in urban areas strengthen regions economically. It can be concluded that “circular cities” would be main drivers on the path to circular economy model implementation in their surrounding regions [118].

The smart economy pillar is also vital because of public services that are proposed by local and regional authorities. Such services, based on ICT and the Internet of Things approach, make it possible to develop new means of communication between local or regional authorities and citizens.

The sharing economy pillar could be treated as an umbrella for a range of non-ownership forms of consumption activities such as swapping, bartering, trading, renting, sharing, and exchanging [117]. Such solutions are the most popular among so-called millennials (people born between the early 1980s and the early 2000s) [116]. The sharing economy reflects the specific lifestyle of its participants based on this access to goods and services without owning [115]. A major shift to employing sharing economy solutions such as collaboration (Zipcar, Traficar, Airbnb, Couchsurfing, etc.) also significantly contributes to CE, due to more efficient usage of existing property, offering society new forms of collaboration, communication, cooperation, and co-working.

The product as service economy pillar is based on so-called “product-service systems” which reflect new types of relationships between producers and their clients, a possibility due to a combination of tangible products and intangible services fulfilling final customer needs [114,122].

The product as service economy pillar and its importance for sustainability and resource efficiency was first discussed in the early 1980s by Walther Stahel [113]. The 21st century saw a new era in this approach, with ICT and innovation contributing dramatically to product-service system development. This development has already started to change buying and owning into renting and leasing of products. The task of regional authorities is to introduce and support relevant initiatives for stimulating consumers and producers to behave according to the rules set by product-service systems. Businesses based on the Product as Service Economy concept stimulate green growth and support CE-based regional development. At the same time, such businesses increase the economic performance of a region and create CE sector jobs.

To summarize, the basic (conceptual) level of the CE regional monitoring framework should include pillars that are the most important and influential for the European concept of CE-based regional development. The pillars identified above were instrumental in preparing the next element of the concept for the CE regional monitoring framework—the main evaluation aspects of the focus areas for CE-based regional development.

3.4.2. Main Aspects of Evaluating CE Regional Monitoring Framework Focus Areas

Identifying key measures for monitoring CE effects within the concept for CE regional monitoring framework focus areas makes it possible to switch from the basic (conceptual) level to the applied (practical) level of the proposed concept for the Framework. Such an evaluation indicates how both levels are interrelated. As the applied (practical) level of the framework should contain indicators for monitoring the progress within each of the CE focus areas, the proposed evaluation criteria would be helpful for the next stages of research focusing on developing a system of indicators for monitoring the progress and effects of CE implementation in a region.

Focus areas for each strategic plan of development prepared by policymakers in the public sector should be estimated on the basis of basic and planned indicators that show the progress and effects of CE [19]. A system of indicators would be the most efficient and the most transparent method of monitoring because, in an examined case, CE would be a core element of strategic development for a region.

Several recent studies were devoted to assessing CE with the help of specific indicators. Different methods were discussed for measuring CE conditions at the micro level and at the level of industrial parks [123,124,125,126]. Some studies dedicated to CE indicators at a regional level were based on Chinese case studies [63,127,128,129,130,131]. There have also been attempts to propose indicators for public management at national and international levels [132].

The majority of regional monitoring indicators were based on an index method where local and regional peculiarities were taken into account. However, a review of those indicators suggests they could not be directly applied for European regions. The national system of circular economy indications that was introduced in China consisted of four main groups—resource output, resource consumption, integrated resource utilization, and waste disposal/pollutant emission indicators [25]. Some of the limitations of this approach were presented in previous sections of the paper. One additional drawback of the Chinese approach is that the same indicators were proposed for both the national and regional levels, thus failing to make a more thorough accounting for region-specific circumstances.

Deeper analyses are needed to investigate which indicators from these earlier studies are appropriate for European realities, and which new or modified indicators should be added for effective monitoring of CE-based regional development. This extends beyond the scope of the current study, but more extensive research is planned by this author in order to propose particular indicators of regional development within the framework. However, one of the tasks for the current study was proposing key aspects for evaluating CE-based regional development within the Framework’s CE focus areas. These evaluation aspects are presented in Table 3 based on the results of the previous research stages—specifically the potential impact of CE on regional development and the CE pillar on which CE monitoring should be based.

Table 3.

Evaluation aspects for CE regional monitoring framework focus areas

Knowing which evaluation aspects are important for monitoring the effects of CE-based regional development makes it possible to propose, in the next step of the research, a relevant and effective system of indicators helpful for regional policymakers.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

This study has focused on recent trends in the European CE model at the regional level. Its findings are intended to help regional policymakers to realize their regions’ full CE potential, improving competitiveness, and making use of all relevant opportunities for smart and sustainable growth. The concept for the CE regional monitoring framework proposed as the main result of the current research is intended to be an additional supporting instrument for developing monitoring actions in order to track the effects of CE-based regional development within the European context.

The concept for the Framework allows regional policymakers to look at CE not only in terms of a traditional regional sustainable development concept covering environmental, social, and economic impacts, but also to pay attention to such areas as spatial and cultural considerations affected by CE implementation. Thus, the CE model contains circular-based spatial planning in the form of circular economy urban planning processes, and by developing industrial and urban symbiosis. Moreover, CE-oriented regional development has the potential to encourage new forms of art, changing mainstream trends in urban design.

The research has also shown that on the one hand, regional policymakers managing a CE transition process can expect numerous benefits and competitive advantages, boosting regional sustainable development, creating new local jobs, and having a positive influence on the wellbeing of a region’s population thanks to such factors as improved environmental quality. On the other hand, CE transformation does come with transitional costs—those related to stimulating CE processes and those that are the effect of implementing a leaner economy model. The current research should help regional authorities to account for the potential pros and cons of CE-based regional development.

As a tool supporting CE regional monitoring, the framework has the following pragmatic and applicable aspects:

- -

- guidance for preparing regional development strategies based on the CE approach through identification of the focus areas and pillars on which CE should be based

- -

- evaluation criteria for monitoring each pillar of the Framework to develop further action plans for CE development within those regions

This study could be characterized as an extension of the current discussion on effective CE monitoring, and specifically as a proposal for which areas and pillars should be the subjects of analysis to evaluate and track CE implementation. The current research was an attempt both to summarize general knowledge and approaches to CE monitoring, and to address the specific character of European and regional CE monitoring actions.

Some limitations of this study are also acknowledged as this research was focused mainly on the basic (conceptual) level of a CE regional monitoring framework—identifying focus areas, pillars, and evaluation aspects that are important for CE-based regional development. The study was not intended to present extensive research into the area of the applied (practical) level of the framework, which has more to do with CE monitoring indicators for instruments supporting regional development and implementation of CE-based strategies. Such limitations will be addressed with the author’s future research into these specifics. Preliminary findings related to existing indicators for CE monitoring will be expanded upon to provide further analysis of their applicability to the CE regional monitoring framework for European countries. Additional indicators will then be proposed to cover all focus areas and supporting pillars of CE-based regional development.

Future studies on the applied (practical) level of the framework should analyze challenges to the operational application of the various pillars in terms of quantifiable indicators. Those challenges would be, first and foremost, caused by the limited access to and sometimes even a lack of needed data for evaluating and monitoring progress towards CE implementation.

Even though there have been attempts to pose the questions which should be answered while realizing the CE monitoring process [82], some of those questions cannot be answered due to numerous gaps in the data collected for tracking CE transitional processes. Thus, the European Environmental Agency’s research devoted to CE implementation and monitoring identified areas for which source information for monitoring-based indicators would be limited [82], such as: average lifetime of selected products, market share of products prepared for reuse and repair services related to them, recycled material quality compared with virgin material quality, the share of remanufacturing business in the manufacturing economy, the involvement of companies in circular company networks, etc.

The limited access to data for CE monitoring is paralleled by limitations in the CE monitoring framework presented by the EC in 2017. The EC framework contains indicators which still are not monitored at the EU level, nor by most Member States, like the level of green public procurement, EU self-sufficiency for raw materials (in %), food waste level, end-of-life recycling input rates, circular material use rate, etc. These deficiencies suggest the development of effective monitoring of CE processes remains at an early stage, and further research is urgently needed to propose indicators to evaluate the progress towards CE at different operational levels.

Even having a set of indicators for monitoring CE processes, it would be difficult to accurately evaluate the aggregate transitional cost of the CE model of regional development. Thus, such estimations should use both qualitative and quantitative methods of analysis to better understand the economic and social effects of CE solutions, and to decide whether the costs of implementing a circular solution are justified by the positive effects on regional development.

The most effective method for qualitative analysis of CE solutions is in-depth interviews with the main stakeholders involved in the transition to a CE model of development. Such interviews could help prepare insights into the most and least successful decisions related to CE practices. The interviewed groups of stakeholders should include CE experts from business, the public sector, and even NGOs and representatives of international organizations if they are involved in regional CE-development activities, in order to have the most complete assessment of all processes which are affected by the transition. Such interviews could also be complemented by collecting opinions regarding transitional costs using surveys from representatives of economic sectors most influenced by CE (energy, automotive, technology and electronics, construction, agriculture, etc.) [121].

In addition to qualitative methods, quantitative methods should be applied for more precise measurements of CE progress and for developing systems of CE regional indicators. Recent research devoted to these measures has used an index method approach [124,129], hierarchical structure model and evaluation index system [127], and fuzzy mathematic and matter elements approaches [130]. A selection and substantiation of methods of qualitative and quantitative analysis could be conducted after more extended research on the specifics of transitional processes that should be evaluated, and the specifics of methods used for those analyses. Such investigations are also planned within the next step of research devoted to the applied (practical) level of the CE regional monitoring framework.

Funding

“This research was funded by European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement no. 665778; The project has also received funding from the National Science Centre, Poland, POLONEZ funding program (project registration number 2015/19/P/HS4/02098)” and “The APC was funded by AGH University of Science and Technology”.

Acknowledgments

This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement no. 665778. The project has also received funding from the National Science Centre, Poland, POLONEZ funding program (project registration number 2015/19/P/HS4/02098).

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest. The founding sponsors had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD). Report from the World Circular Economy Forum; International Institute for Sustainable Development: Winnipeg, MB, Canada, 2017; Volume 208, No. 20. [Google Scholar]

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation (EMF). Towards the Circular Economy Vol. 1: An Economic and Business Rationale for an Accelerated Transition; Ellen MacArthur Foundation (EMF): Cowes, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- McDowall, W.; Geng, Y.; Huang, B.; Bartekova, E.; Bleischwitz, R.; Turkeli, S.; Kemp, R.; Domenech, T. Circular Economy Policies in China and Europe. J. Ind. Ecol. 2017, 21, 651–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchherr, J.; Reike, D.; Hekkert, M. Conceptualizing the circular economy: An analysis of 114 definitions. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 127, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smol, M.; Kulczycka, J.; Avdiushchenko, A. Circular economy indicators in relation to eco-innovation in European regions. Clean Technol. Environ. 2017, 19, 669–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korhonen, J.; Nuur, C.; Feldmann, A. Circular economy as an essentially contested concept. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 175, 544–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reike, D.; Walter, J.V.; Vermeulen, W.J.V.; Witjes, S. The circular economy: New or Refurbished as CE 3.0?—Exploring Controversies in the Conceptualization of the Circular Economy through a Focus on History and Resource Value Retention Options. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 135, 246–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieto-Sandoval, V.; Ormazabal, C.J.M. Towards a consensus on the circular economy. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 179, 605–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.; Bi, J.; Moriguichi, Y. The circular economy: A new development strategy in China. J. Ind. Ecol. 2008, 10, 4–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, A.; Skene, K.; Haynes, K. The Circular Economy: An Interdisciplinary Exploration of the Concept and Application in a Global Context. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 140, 369–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commission of European Communities. Report from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions on the implementation of the Circular Economy Action Plan (COM (2017), 33); Communication No. 33; Commission of European Communities: Brussels, Belgium, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Eurostat: CE Overview. 2018. Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/circular-economy (accessed on 1 September 2018).

- Ranta, V.; Aarikka-Stenroosa, L.; Ritala, P.; Mäkinena, S.J. Exploring institutional drivers and barriers of the circular economy: A cross regional comparison of China, the US, and Europe. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 135, 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission Directorate-General (EC, DG) for Communication Citizens Information. The European Union Explained: Regional Policy; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2014; Available online: https://europa.eu/european-union/topics/regional-policy_en (accessed on 1 September 2018). [CrossRef]

- Commission of European Communities. Cohesion Policy Support for the Circular Economy; Commission of European Communities: Brussels, Belgium, 2016; Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/en/policy/themes/environment/circular_economy/ (accessed on 1 September 2018).

- Commission of European Communities. Towards a Circular Economy: A Zero Waste Programme for Europe (COM (2014), 398); Communication No. 398; Commission of European Communities: Brussels, Belgium, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Pact of Amsterdam. Urban Agenda for the EU. 2016. Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/sources/policy/themes/urban-development/agenda/pact-of-amsterdam.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2018).

- Interreg Europe. 2016. Available online: https://www.interregeurope.eu/retrace/news/news-article/144/promoting-circular-economy/ (accessed on 20 August 2018).

- Van Dooren, W.; Bouckaert, G.; Halligan, J. Performance Management in the Public Sector, 2nd ed.; Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2015; ISBN 978-1-315-81759-0. [Google Scholar]

- Boulding, K.E. The economics of coming spaceship earth. In Environmental Quality in a Growing Economy; Jarrett, H., Ed.; Resources for the Future/Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1966; pp. 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Skene, K.R. Circles, spirals, pyramids and cubes: Why the circular economy cannot work. Sustain. Sci. 2018, 13, 479–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triebswetter, U.; Hitchens, D. The impact of environmental regulation on competitiveness in the German manufacturing industry: A comparison with other countries of the European Union. J. Clean. Prod. 2005, 13, 733–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriguchi, Y. Material flow indicators to measure progress toward a sound material-cycle society. J. Mater. Cycles Waste 2007, 9, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilitewski, B. Circular Economy in Germany. In Proceedings of the Eleventh International Waste Management and Landfill Symposium, Cagliari, Italy, 1–5 October 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Geng, Y.; Fu, J.; Sarkis, J.; Xue, B. Towards a national circular economy indicator system in China: An evaluation and critical analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2012, 23, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, G.; Li, Y. The Effect of Reinforcing the Concept of Circular Economy in West China Environmental Protection and Economic Development. Procedia Environ. Sci. 2012, 12, 785–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; Qi, C. Countermeasures towards Circular Economy Development in West Regions. Energy Procedia 2012, 16(Pt. B), 927–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Directive 2008/98/EC of The European Parliament and of The Council of 19 November 2008 on Waste. Off. J. Eur. Union 2008. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32008L0098&from=EN (accessed on 1 September 2018).

- Communication from the Commission. Europe 2020. A Strategy for Smart, Sustainable and Inclusive Growth (COM (2010), 2020); Communication No. 2020; Commission of European Communities: Brussels, Belgium, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation (IMF). Towards the Circular Economy Volume 2: Opportunities for the Consumer Goods Sector; Ellen MacArthur Foundation (EMF): Cowes, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation (EMF). Towards the Circular Economy Volume 3: Accelerating the Scale-Up across Global Supply Chains; Ellen MacArthur Foundation (EMF): Cowes, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation (EMF). Growth within: A Circular Economy Vision for a Competitive Europe; Ellen MacArthur Foundation (EMF): Cowes, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation (EMF). Towards a Circular Economy: Business Rationale for an Accelerated Transition; Ellen MacArthur Foundation (EMF): Cowes, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation (EMF). Delivering the Circular Economy: A Toolkit for Policymakers; Ellen MacArthur Foundation (EMF): Cowes, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation (EMF). The New Plastics Economy: Rethinking the Future of Plastics; Ellen MacArthur Foundation (EMF): Cowes, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation (EMF). Circular Economy in India: Rethinking Growth for Long-Term Prosperity; Ellen MacArthur Foundation (EMF): Cowes, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation (EMF). The Circular Economy Opportunity for Urban & Industrial Innovation in China; Ellen MacArthur Foundation (EMF): Cowes, UK, 2018; Available online: https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/assets/downloads/The-circular-economy-opportunity-for-urban-industrial-innovation-in-China_19-9-18_1.pdf (accessed on 28 October 2018).

- European Commission, Innovation Union. A Europe 2020 Initiative. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/research/events/eib/ic2014/speaker.cfm?id=58 (accessed on 1 November 2018).

- Commission of European Communities. Closing the Loop—An EU Action Plan for the Circular Economy (COM (2015), 614); Communication No. 614; Commission of European Communities: Brussels, Belgium, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation (EMF). News. 2015. Available online: https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/news/circular-economy-would-increase-european-competitiveness-and-deliver-better-societal-outcomes-new-study-reveals (accessed on 28 October 2018).

- European Commission. Circular Economy Research and Innovation—Connecting Economic and Environmental Gains; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2017; Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/programmes/horizon2020/sites/horizon2020/files/ce_booklet.pdf (accessed on 28 October 2018). [CrossRef]

- Commission of European. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, The Council, The European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions a European Strategy for Plastics in a Circular Economy; Communities No 28; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2018; Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/environment/circular-economy/pdf/plastics-strategy.pdf (accessed on 28 October 2018).

- European Commission. Joint Research Centre 2017. Critical Raw Materials and the Circular Economy. Available online: http://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/bitstream/JRC108710/jrc108710-pdf-21-12-2017_final.pdf (accessed on 28 October 2018).

- Dutch Ministry of Environment. A Circular Economy in the Netherlands by 2050. 2016. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/environment/ministerial/whatsnew/2016-ENV-Ministerial-Netherlands-Circular-economy-in-the-Netherlands-by-2050.pdf (accessed on 28 October 2018).

- Sitra Foundation. Leading the Cycle Finnish Road Map to a Circular Economy 2016–2025. Sitra Studies 121. 2016. Available online: https://media.sitra.fi/2017/02/24032659/Selvityksia121.pdf (accessed on 28 October 2018).

- Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation, Building and Nuclear Safety. Germany-German Resource Efficiency Programme (ProgRess II). 2016. Available online: http://www.bmub.bund.de/fileadmin/Daten_BMU/Pools/Broschueren/german_resource_efficiency_programme_ii_bf.pdf (accessed on 14 October 2018).

- Ministry of Environment of Portugal. Leading the Transition: A Circular Economy Action Plan for Portugal: 2017–2020. 2017. Available online: https://circulareconomy.europa.eu/platform/sites/default/files/strategy_-_portuguese_action_plan_paec_en_version_3.pdf (accessed on 14 October 2018).

- Ministry for the Environment, Land and Sea Ministry of Economic Development. Towards a Model of Circular Economy for Italy—Overview and Strategic Framework. 2017. Available online: https://circulareconomy.europa.eu/platform/sites/default/files/strategy_-_towards_a_model_eng_completo.pdf (accessed on 14 October 2018).

- The French Ministry of Ecological and Solidarity Transition. France Unveils Circular Economy Roadmap. 2018. Available online: https://www.ecologique-solidaire.gouv.fr/sites/default/files/FREC%20-%20EN.pdf (accessed on 14 October 2018).

- Košir, L.G.; Korpar, N.; Potočnik, J.; Kocjančič, R. Proposal for a Uniform Document on the Potentials and Opportunities for the Transition to a Circular Economy in Slovenia; Slovenia, 2018; pp. 1–56. Available online: http://www.vlada.si/fileadmin/dokumenti/si/projekti/2016/zeleno/ROADMAP_TOWARDS_THE_CIRCULAR_ECONOMY_IN_SLOVENIA.pdf (accessed on 14 October 2018).

- The Government of Catalonia. Promoting Green and Circular Economy in Catalonia: Strategy of the Government of Catalonia. 2015. Available online: https://circulareconomy.europa.eu/platform/strategies; http://mediambient.gencat.cat/web/.content/home/ambits_dactuacio/empresa_i_produccio_sostenible/economia_verda/impuls/IMPULS-EV_150519.pdf (accessed on 14 October 2018).

- Ministry of Housing, Quality of Life, Environment and Energy of Belgium; Minister of the Economy, Employment and Professional Training. Programme Régional En Economie Circulaire 2016–2020. 2016. Available online: http://document.environnement.brussels/opac_css/elecfile/PROG_160308_PREC_DEF_FR (accessed on 14 October 2018).

- The Scottish Government. A Circular Economy Strategy for Scotland Report. 2016. Available online: https://circulareconomy.europa.eu/platform/sites/default/files/making_things_last.pdf (accessed on 14 October 2018).

- City Government of Amsterdam. Circular Amsterdam: A Vision and Action Agenda for the City and Metropolitan Area. 2016. Available online: https://www.circle-economy.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Circular-Amsterdam-EN-small-210316.pdf (accessed on 14 October 2018).

- City Government of Paris. White Paper on the Circular Economy of the Greater Paris. 2016. Available online: https://api-site.paris.fr/images/77050 (accessed on 14 October 2018).

- Regional Government of Extremadura. Extremadura 2030: Strategy for a Green and Circular Economy. 2017. Available online: http://extremadura2030.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/estrategia2030.pdf (accessed on 14 October 2018).

- London Waste and Recycling Board. London’s Circular Economy Route Map. 2017. Available online: https://www.lwarb.gov.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/LWARB-London%E2%80%99s-CE-route-map_16.6.17a_singlepages_sml.pdf (accessed on 14 October 2018).

- Vlaanderen Circulair. Circular Flanders Kick-Off Statement. 2017. Available online: https://circulareconomy.europa.eu/platform/sites/default/files/kick-off_statement_circular_flanders.pdf (accessed on 14 October 2018).

- Thürer, M.; Pan, Y.H.; Qu, T.; Luo, H.; Li, D.C.; Huang, G.Q. Internet of Things (IoT) driven kanban system for reverse logistics: Solid waste collection. J. Intell. Manuf. 2016, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobre, G.C.; Tavares, E. Scientific literature analysis on big data and internet of things applications on circular economy: A bibliometric study. Scientometrics 2017, 111, 463–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, M.S. An introductory note on the environmental economics of the circular economy. Sustain. Sci. 2007, 2, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]