Social Life Cycle Assessment: Specific Approach and Case Study for Switzerland

Abstract

1. Introduction

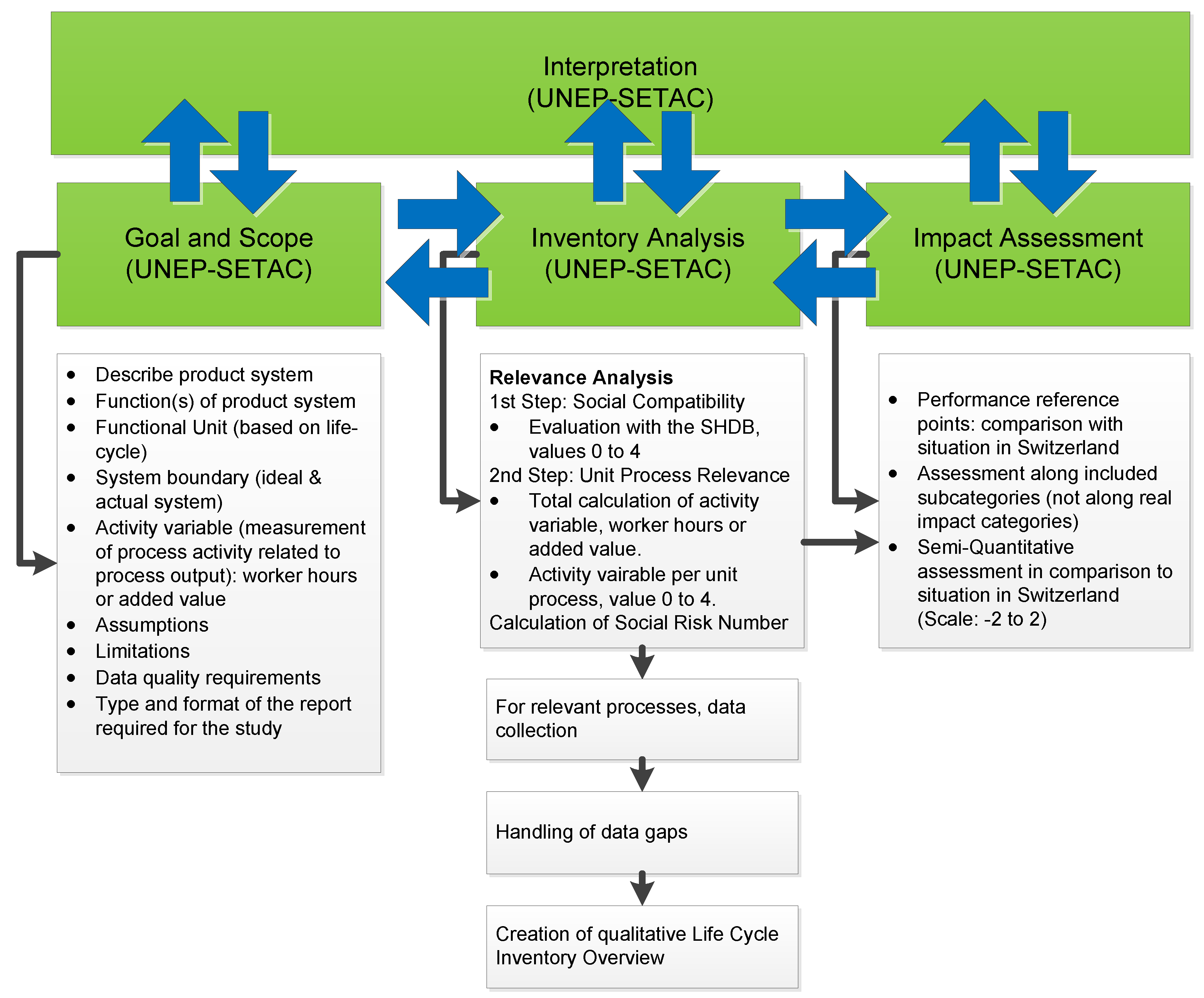

1.1. Social Life Cycle Assessment

1.2. The Proposed Specific Approach to the S-LCA and the Case Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Goal & Scope

- For each UNEP–SETAC subcategory, the best corresponding SHDB table theme in regard to content was assigned. The judgment of “best corresponding” was left to the practitioner.

- Multiple SHDB table themes per UNEP–SETAC subcategory are possible.

- For each SHDB table theme, only one issue is defined for assessment.

- The following criteria for defining the issues were applied:

- ○

- As general as possible (for example, total child labour instead of female child labour)

- ○

- Issues from the Social Hotspot Index were the priority

- Sector-specific issues are preferred.

2.2. Relevance Analysis

2.2.1. First Step of the Relevance Analysis: Social Compatibility

2.2.2. Second Step of the Relevance Analysis: Unit Process Relevance

- Added monetary value (AMV in $): The more added value a single unit process has, the more important it is to investigate its social impacts. In this manner, the AMV of the unit process under assessment (AMVPS) is evaluated according to the discrete intervals proposed in Table 2. As such, the activity variable obtains a value from 1 to 4, with 1 being an insignificant added value and 4 a very significant added value.

- WHs: If the unit process is work-intensive then it is important to investigate it. WHs are measured in hours (h) and refer to the time a worker requires to carry out such a unit process. Analogously to the monetary approach, the WHs are evaluated on a discrete scale (see Table 2) and thus the unit process obtains a value from 1 to 4, where 1 is almost no worker time involved and 4 is very labour intensive. It is worth noting that for the case study in this paper, WHs were selected as the activity variable.

2.2.3. Calculating the Social Relevance Number

- SRN: Social Relevance Number

- SC: Social Compatibility

- UPR: Unit Process Relevance

2.3. Social Life Cycle Inventory

2.4. Social Life Cycle Impact Assessment

2.4.1. Swiss Performance Reference Points

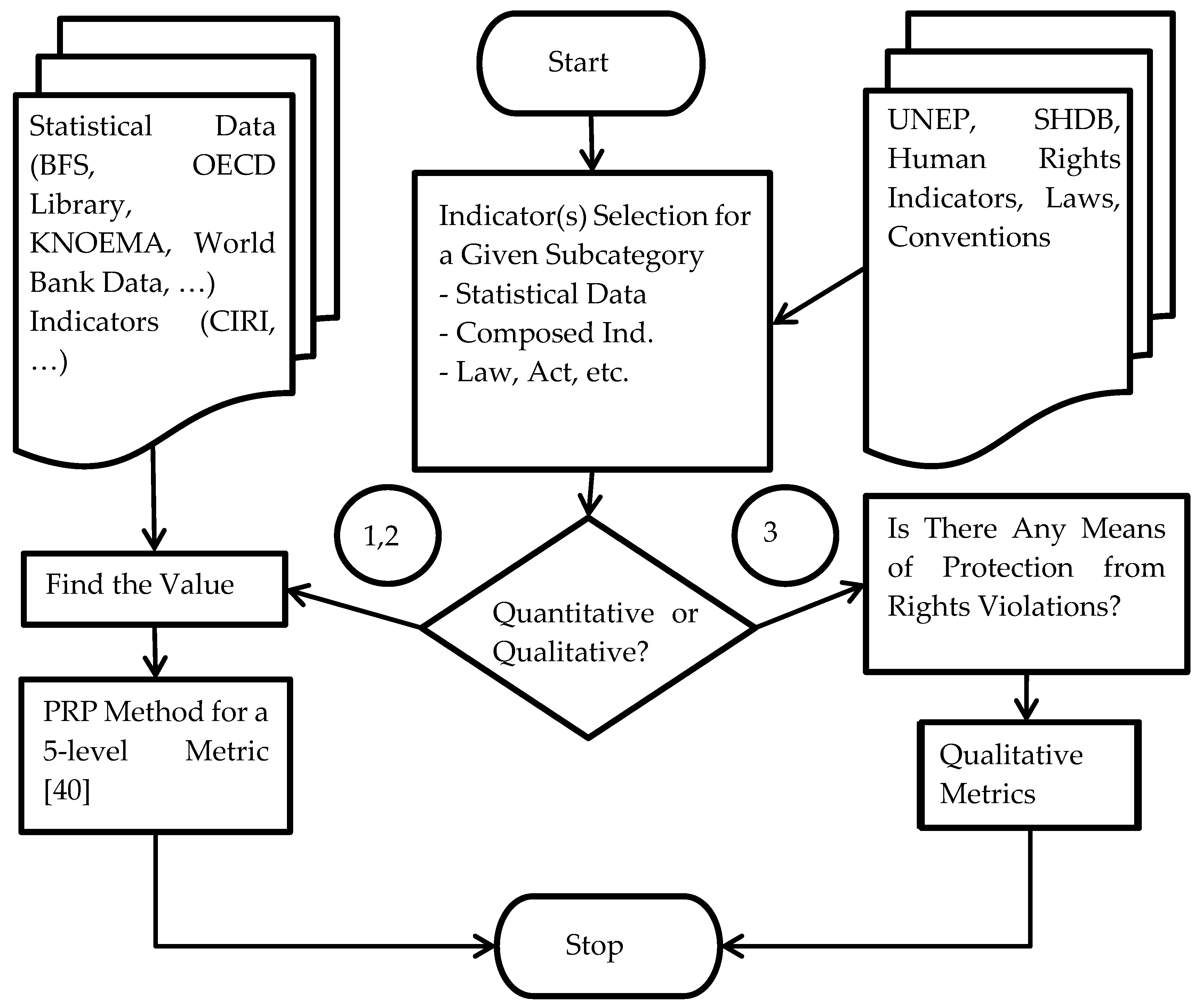

- Quantitative: The data have to be clearly defined and shall be as quantifiable and objective as possible (that is, statistical data based on facts).

- Semiquantitative: If no quantifiable relevant data can be found, semi-quantifiable data shall be chosen (that is, composed of indicators from different organisations).

- Qualitative: If no quantifiable or semiquantifiable relevant data can be found, the situation has to be described qualitatively. This mainly involves assessing a given threat in a geographical region or the state’s efforts at fighting a given threat to human rights.

Quantitativee and Semiquantitative Indicators

- The range and the resolution of the original indicator are smaller than those of the PRP.

- -

- Example: Characteristic CIRI indicators are discrete and are often just between 0 and 2 or 3.

- -

- Possible solution: Reduce the PRP range and metric by transposing the original indicators to the PRP values (for example, an index with possible values of 0, 1 and 2 would become PRP −2, −1 and 0, as long as the reference situation has an index value of 2).

- The reference (Switzerland) which, per definition, scores 0 SRPR, has the maximal (or minimal) possible value of the original indicator. In this case, half of the SPRP scale cannot be used, which results in a loss of resolution.

- -

- Example: This is characteristic of CIRI indicators and statistical data expressed in rates where the reference values are near 100% or 0%.

- -

- Possible solution: Reduce the PRP range and use only half of the scale.

- The PRP may give the wrong idea about the situation when the defined percentage in Table 4 is not proportional with a real difference in the indicator.

- -

- Example: This can happen with many indicators, since there is no given reason for proportionality between the methodology according to authors of a previous paper [40] and the real indicator’s behaviour. This possible distortion is also the most difficult to recognise. Good practice involves taking a general view of the distribution of the total statistical data available and estimating how many countries would end up with which SPRP.

- -

- Possible solution: Define a specific scale for just this indicator on the basis of the indicator itself, international standards, or recommended practices. One strategy could be to check the statistical distribution and adjust the SPRP levels so that the nations are evenly distributed between the SPRP.

Qualitative Indicators

Prioritisation of Legislative Levels

General Consideration of the Reference Situation Switzerland

Example of Swiss Performance Reference Point Definitions

2.5. Interpretation

3. Results of the Case Study

3.1. Goal & Scope

- The material is present in most electric appliances.

- It is of importance for the energy industry.

- It is mined in both small (artisanal) and large-scale mining operations.

- Delocalisation and Migration (DM)—KI: Risk that a country has not ratified international conventions or set up policies for immigrants

- Access to material resources (RM)—KI: Risk of no access to an improved source of sanitation

- Child Labour (CH)—KI: Risk of child labour in the sector

- Forced Labour (FL)—KI: Risk of forced labour in the sector

3.2. Relevance Analysis: The Case of Copper

3.2.1. First Step of the Relevance Analysis: Social Compatibility: The Case of Copper

3.2.2. Second Step of the Relevance Analysis: Unit Process Relevance: The Case of Copper

3.2.3. Calculating the Social Relevance Number: The Case of Copper

3.3. Social Life Cycle Inventory: The Case of Copper

3.3.1. Mining in the Democratic Republic of the Congo

Delocalisation and Migration

Access to Material Resources

Child Labour

Forced Labour

3.3.2. Mining in Chile

Delocalisation and Migration

3.3.3. Processing in Turkey

3.4. Social Life Cycle Impact Overview: The Case of Copper

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, J.-J.; Jing, Y.-Y.; Zhang, C.-F.; Zhao, J.-H. Review on multi-criteria decision analysis aid in sustainable energy decision-making. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2009, 13, 2263–2278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neugebauer, S.; Traverso, M.; Scheumann, R.; Chang, Y.-J.; Wolf, K.; Finkbeiner, M. Impact pathways to address social well-being and social justice in SLCA—Fair wage and level of education. Sustainability 2014, 6, 4839–4857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jørgensen, A.; Finkbeiner, M.; Jørgensen, M.S.; Hauschild, M.Z. Defining the baseline in social life cycle assessment. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2010, 15, 376–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swiss National Science Foundation. Energy Turnaround Nationale Research Programme NRP 70; SNSF: Bern, Switzerland, 2015; Available online: http://www.nfp70.ch/en (accessed on 15 August 2018).

- Maxim, A. Sustainability assessment of electricity generation technologies using weighted multi-criteria decision analysis. Energy Policy 2014, 65, 284–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaaban, M.; Scheffran, J.; Böhner, J.; Elsobki, M.S. Sustainability assessment of electricity generation technologies using weighted multi-criteria decision analysis. Energies 2018, 11, 1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmer, K.; Fröhling, M.; Breun, P.; Schultmann, F. Assessing social risks of global supply chains: A quantitative analytical approach and its application to supplier selection in the German automotive industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 149, 96–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015; Volume 16301. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, R.; Yang, D.; Chen, J. Social Life Cycle Assessment Revisited. Sustainability 2014, 6, 4200–4226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNEP-SETAC. Guidelines for Social Life Cycle Assessment of Products; UNEP-SETAC: Paris, France, 2009; Volume 15, ISBN 9789280730210. [Google Scholar]

- Benoît, C.; Norris, G.A.; Valdivia, S.; Ciroth, A.; Moberg, A.; Bos, U.; Prakash, S.; Ugaya, C.; Beck, T. The guidelines for social life cycle assessment of products: Just in time! Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2010, 15, 156–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corona, B.; Bozhilova-Kisheva, K.P.; Olsen, S.I.; San Miguel, G. Social Life Cycle Assessment of a Concentrated Solar Power Plant in Spain: A Methodological Proposal. J. Ind. Ecol. 2017, 21, 1566–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benoît Norris, C.; Traverso, M.; Valdivia, S.; Vickery-Niederman, G.; Franze, J.; Azuero, L.; Ciroth, A.; Mazijin, B.; Aulisio, D. The Methodological Sheets for Sub-categories in Social Life Cycle Assessment (S-LCA); UNEP-SETAC: Paris, France, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Chhipi-Shrestha, G.K.; Hewage, K.; Sadiq, R. ‘Socializing’ sustainability: A critical review on current development status of social life cycle impact assessment method. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2015, 17, 579–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parent, J.; Cucuzzella, C.; Revéret, J.-P. Impact assessment in SLCA: Sorting the sLCIA methods according to their outcomes. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2010, 15, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo Garrido, S.; Parent, J.; Beaulieu, L.; Revéret, J. A literature review of type I SLCA: Making the logic underlying methodological choices explicit. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2016, 23, 432–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- New Earth Social Hotspot Database. Available online: http://socialhotspot.org/ (accessed on 15 August 2018).

- Hosseinijou, S.A.; Mansour, S.; Shirazi, M.A. Social life cycle assessment for material selection: A case study of building materials. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2014, 19, 620–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talantsev, A. A Systematic Approach to Reputation Risk Assessment. In Modelling, Computation and Optimization in Information Systems and Management Sciences; Le Thi, H.A., Pham Dinh, T., Nguyen, N.T., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 461–473. [Google Scholar]

- Interdepartementaler Ausschuss Nachhaltige Entwicklung (IDANE). Nachhaltige Entwicklung in der Schweiz: Ein Wegweiser; IDANE: Bern, Switzerland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Jørgensen, A.; Le Bocq, A.; Nazarkina, L.; Hauschild, M. Methodologies for social life cycle assessment. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2008, 13, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austrian Standards Plus. ÖNORM ISO 3100:2010, 2nd ed.; Austrian Standards Instiute: Vienna, Austria, 2014; ISBN 978-3-85402-295-4. [Google Scholar]

- Dreyer, L.C.; Hauschild, M.Z.; Schierbeck, J. A framework for social life cycle impact assessment. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2006, 11, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federal Statistical Office. Statistical Data on Switzerland 2015; Federal Statistical Office Section Dissemination and Publications: Neuchâtel, Switzerland, 2015; ISBN 9783303005309. [Google Scholar]

- Walter, P.; Herrmann, A.B.; Cangemi, V.; Murier, T.; Perrenoud, S.; Reutter, R.; Saucy, F.; Schmassmann, S. Arbeitsmarktindikatoren 2015; Bundesamt für Statistik: Neuchâtel, Switzerland, 2015; ISBN 9783303032763. [Google Scholar]

- Kraszewska, K.; Knauth, B.; Thorogood, D. Indicators of Immigrant Integration: A Pilot Study; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, Luxembourg, 2011; ISBN 978-92-79-20238-4. [Google Scholar]

- Eurostat. The Measurement of Poverty and Social Inclusion in the EU: Achievements and Further Improvements; UNECE: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- UNDP. Human Development Report 2015: Work for Human Development; United Nations Development Programme: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation. World Health Statistics 2015; World Health Organisation: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015; ISBN 9780874216561. [Google Scholar]

- The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Health at a Glance 2015: OECD Indicators; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2015; ISBN 978-92-64-24351-4. [Google Scholar]

- Cingranelli, D.L.; Richards, S.D.L.; Clay, C.K.C. CIRI Human Rights Data Project: Short Variable Description, 2013.

- Cingranelli, D.L.; Richards, S.D.L.; Clay, C.K.C. CIRI Data 1981–2011. Available online: http://www.humanrightsdata.com/p/data-documentation.html (accessed on 15 August 2018).

- Messner, J.J.; Haken, N.; Taft, P.; Blyth, H.; Lawrence, K.; Graham, S.P.; Umana, F. Fragile States Index 2015; Fund for Peace: Washington, DC, USA, 2015; pp. 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO Institute for Statistics. Data Centre: Out of School Children. Available online: http://uis.unesco.org/en/topic/out-school-children-and-youth (accessed on 15 August 2018).

- Diallo, Y.; Etienne, A.; Mehran, F. Global Child Labour Trends 2008 to 2012; IPEC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Business Social Compliance Initiatie (BSCI). BSCI Code of Conduct; Foreign Trade Association: Brussels, Belgium, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF. Child Labour Database. Available online: https://data.unicef.org/topic/child-protection/child-labour/ (accessed on 15 August 2018).

- Sano, H.; McInerney-Lankford, S. Human Rights Indicators in Development. A World Bank Study; The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development: Washington, DC, USA, 2010; ISBN 9780821386040. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Human Rights. Human Rights Indicators: A Guide to Measurement and Implementation; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2012; ISBN 9211541980. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, C.-W.; Wang, S.-W.; Hu, A.H. Development of a New Methodology for Impact Assessment of SLCA. In Proceedings of the 20th CIRP International Conference on Life Cycle Engineering, Singapore, 17–19 April 2013; pp. 469–473. [Google Scholar]

- Transparency International Corruption Perceptions Index 2014: Results. Available online: https://www.transparency.org/cpi2014/results (accessed on 16 August 2018).

- Amnesty International. Amnesty International Report: The State of the World’s Human Rights; Amnesty International: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Die Bundesversammlung der Schweizerischen Eidgenossenschaft. Bundesgesetz über die Ausländerinnen und Ausländer, 2015th ed.; Die Bundesversammlung der Schweizerischen Eidgenossenschaft: Bern, Switzerland, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Human Rights Watch. Democratic Republic of Congo Events of 2017. Available online: https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2018/country-chapters/democratic-republic-congo (accessed on 22 January 2018).

- Tsurukawa, N.; Prakash, S.; Manhart, A. Social Impacts of Artisanal Cobalt Mining in Katanga, Democratic Republic of Congo; Institute for Applied Ecology: Freiburg, Germany, 2011; Volume 49. [Google Scholar]

- Vanbrabant, Y.; Burlet, C.; Goethals, H.; Thys, T. Multidisciplinary characterisation of heterogenite—Oxidized cobalt ore deposits (Katanga Province, Democratic Republic of Congo). In Proceedings of the Colloque Quête des Ressources II, Tervuren, Belgium, 1–3 December 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Meersohn, S. La producción de cobre de Minera Escondida fue de 97.103 toneladas. Area Minera 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bechtel. Escondida Phase IV. Available online: http://www.bechtel.com/projects/escondida-phase-iv-expansion/ (accessed on 16 August 2018).

- Dirección del Trabajo. ENCLA 2014. Informe de Resultados Octava Encuesta Laboral; Salinero Berardi, J., Ed.; Dirección del Trabajo: Santiago de Chile, Chile, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Demirer Kablo. Demirer Manufacturing Process. Available online: http://www.demirerkablo.com/demİrer/factory-manufacturing-process.aspx (accessed on 19 January 2018).

- Manhart, A.; Schleicher, T. Conflict Minerals: An Evaluation of the Dodd-Frank Act and Other Resource-Related Measures; Institute for Applied Ecology: Freiburg, Germany, 2013; Volume 49. [Google Scholar]

- Zorba, L.; Sarich, J.; Stauss, K. The Congo Report: Slavery in Conflict Minerals; Free the Slaves: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Jeska, A. Sklaverei im Kongo: Arbeiten, wo der Teufel Wohnt. Available online: https://www.welt.de/politik/ausland/article106139906/Sklaverei-im-Kongo-Arbeiten-wo-der-Teufel-wohnt.html (accessed on 16 August 2018).

- Grown, C. How Mining Affects Women in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2015/09/how-mining-affects-women-in-the-democratic-republic-of-congo/ (accessed on 30 January 2018).

- ITUC. Report for the WTO General Council Review of the Trade Policies of Democratic Republic of Congo; ITUC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Source Intelligence. What are Conflict Minerals? Available online: https://www.sourceintelligence.com/what-are-conflict-minerals/ (accessed on 16 August 2018).

- Heath, N. How Conflict Minerals Funded a War That Killed Millions, and Why Tech Giants Are Finally Cleaning Up Their Act. Available online: https://www.techrepublic.com/article/how-conflict-minerals-funded-a-war-that-killed-millions/ (accessed on 16 August 2018).

- Coderre-Proulx, M.; Campbell, B.; Mandé, I. International Migrant Workers in the Mining Sector; International Labour Office: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016; ISBN 978-92-2-128888-6. [Google Scholar]

- Bundesversammlung der Schweizerischen Eidgenosseschaft. Bundesgesetz über die Arbeit in Industrie, Gewerbe und Handel, 2013th ed.; Die Bundesversammlung der Schweizerischen Eidgenossenschaft: Bern, Switzerland, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Bundesversammlung der Schweizerische Eidgenossenschaft. Konvention zum Schutze der Menschenrechte und Grundfreiheiten, 2012th ed.; Bundesversammlung der Schweizerische Eidgenossenschaft: Bern, Switzerland, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Blanco, J.; Lehmann, A.; Muñoz, P.; Antón, A.; Traverso, M.; Rieradevall, J.; Finkbeiner, M. Application challenges for the social Life Cycle Assessment of fertilizers within life cycle sustainability assessment. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 69, 34–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekener-Petersen, E.; Finnveden, G. Potential hotspots identified by social LCA—Part 1: A case study of a laptop computer. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2013, 18, 127–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, D.W.; Fanning, A.L.; Lamb, W.F.; Steinberger, J.K. A good life for all within planetary boundaries. Nat. Sustain. 2018, 1, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank Group: International Development, Poverty, Sustainability. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/ (accessed on 16 August 2018).

- United Nations. Available online: http://www.un.org/en/index.html (accessed on 16 August 2018).

- Helliwell, J.F.; Layard, R.; Sachs, J.D. World Happiness Report 2018, New York, NY, USA, 2018.

| SHDB Rating | Social Compatibility | Category Social Compatibility |

|---|---|---|

| Evidence of no risk | Very high social compatibility | 0 |

| Low | High social compatibility | 1 |

| Medium | Limited social compatibility | 2 |

| High | Low social compatibility | 3 |

| Very high | Very low social compatibility | 4 |

| No data | Unknown social compatibility but considered relevant due to lack of information | n/a |

| Activity Variable’s Threshold of Cruciality in % | Relevance in Life Cycle | Unit Process Relevance (UPR) |

|---|---|---|

| >0 to 1% | Low relevance | 1 |

| 1% to 5% | Medium relevance | 2 |

| 5% to 10% | High relevance | 3 |

| >10% | Very high relevance | 4 |

| No data | Possibly high relevance | 1 to 4 (according to own estimation) |

| Organisation | Main Publications/Data Sets | Online Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Federal Statistical Office | Statistical Data on Switzerland [24] Labour market indicators [25] | www.bfs.admin.ch |

| Eurostat | Indicators of Immigrant Integration—A Pilot Study [26] The measurement of poverty and social inclusion in the EU: achievements and further improvements [27] | www.ec.europa.eu/eurostat |

| United Nations Development Program | Human Development Report 2015 [28] | www.hdr.undp.org |

| World Health Organisation (WHO) | World health statistic 2015 [29] | www.who.int/gho/en/ |

| The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) | Health at a glance 2015: OECD Indicators [30] | www.oecd-ilibrary.org/ and data.oecd.org/ |

| CIRI Human Rights Data Project | CIRI Human Rights—Short Variable Description [31] CIRI Data Online [32] | www.humanrightsdata.com |

| The Fund for Peace | Fragile States Index [33] | www.fsi.fundforpeace.org/ |

| United Nations Educational Scientific Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) | UNESCO Institute for Statistics [34] | www.data.uis.unesco.org/ |

| International Labour Office | Global child labour trends 2008 to 2012 [35] | www.ilo.org/ |

| Business Social Compliance Initiative | BSCI Code of Conduct [36] | www.bsci-intl.org/ |

| United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF) | UNICEF Child labour database [37] | www.unicef.org/ |

| The World Bank | Human Rights Indicators in Development. A World Bank Study [38] | www.worldbank.org/ |

| United Nations Human Rights (UNHR) | Human Rights Indicators: A Guide to Measurement and Implementation [39] | www.ohchr.org |

| Observation | PRP Value | % of Reference for Positive Indicator | % of Reference for Negative Indicator |

|---|---|---|---|

| Really worse than reference | −2 | <25% | >175% |

| Worse than reference | −1 | 25–75% | 125–175% |

| Same as reference | 0 | 75–125% | 75–125% |

| Better than reference | 1 | 125–175% | 25–75% |

| Really better than reference | 2 | >175% | <25% |

| Indicator 1 (Quantitative) | Indicator 2 (Qualitative) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subcategory | Delocalisation and Migration | |||||||

| Example of Indicators UNEP | Integration for migrant workers | |||||||

| SHDB Issue | Risk that a country has not ratified international conventions or set up policies for immigrants | |||||||

| Explicit Indicator | Foreign unemployment/total unemployment | Is there a law regulative for the immigration and integration of immigrants? Does it promote integration? If yes, does it seem to be enforceable? | ||||||

| Situation in Switzerland | 7.9%/4.4% = 1.8 [24] | The federal law on foreigners [43] defines the admission (Art. 3) and the integration (Art. 4) of immigrant workers. What is decisive for admission is the interest of the national economy, whereby it is explicitly stated that sustainable integration and the social environment are crucial aspects. | ||||||

| Swiss Performance Reference Points Levels | −2 > 3.15 | −1 > 2.25 and <3.15 | 0 > 1.35 and <2.25 | +1 > 0.45 and <1.35 | −2 < 0.45 | −2 There is a law on immigration, but it does not really promote integration | −1 There is a law, it promotes integration, but it does not seem to be enforceable | 0 There is a law, it promotes integration and it seems to be enforceable |

| LCA-Phase 1: Raw Material Extraction | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Process 1: Copper Mining | |||||||

| 1st Step Social Compatibility | Activity Variable Value [% of total Working Hours] | 2nd Step Unit Process Relevance | Social Relevance Number | If Relevant, Qualitative Assessment of Sector | SPRP | ||

| DM | Congo, DR | n/a | 2.3% | 2 | n/a | Relevant | −1 |

| Chile | 3 | 1.7% | 2 | 6 | Relevant | 0 | |

| MR | Congo, DR | 4 | 2.3% | 2 | 8 | Relevant | −2 |

| Chile | 1 | 1.7% | 2 | 2 | Not Relevant | 0 | |

| CH | Congo, DR | 4 | 2.3% | 2 | 8 | Relevant | −2 |

| Chile | 1 | 1.7% | 2 | 2 | Not Relevant | 0 | |

| FL | Congo, DR | 4 | 2.3% | 2 | 8 | Relevant | −1 |

| Chile | 2 | 1.7% | 2 | 4 | Not Relevant | 0 | |

| LCA-Phase 2: Production | |||||||

| Process 2: Copper Processing | |||||||

| 1st Step Social Compatibility | Activity Variable Value [% of total Working Hours] | 2nd Step Unit Process Relevance | Social Relevance Number | If relevant, qualitative assessment of sector | SPRP | ||

| DM | Turkey [h] | 3 | 0.02% | 1 | 3 | Not Relevant | 0 |

| MR | Turkey [h] | 2 | 0.02% | 1 | 2 | Not Relevant | 0 |

| CH | Turkey [h] | 1 | 0.02% | 1 | 1 | Not Relevant | 0 |

| FL | Turkey [h] | 3 | 0.02% | 1 | 3 | Not Relevant | −1 |

| Mining/DRC | Value | Unit | Source/Comment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total time to finish product | 70 | [h/finished product] | Assumption |

| Mass copper in product | 16 | [kg Cu] | |

| Proportion provenance | 0.05 | [kg Cu DRC/kg Cu] | Assumption |

| Mass in unit process | 0.80 | [kg Cu] | |

| Worker hours per 50-kg bag | 11 | [h/bag] | Assumption based on a past paper [45] “11 to 26 worker hours per bag” |

| CuO concentration in ore | 0.14 | [h] | [46] |

| Pure Cu in CuO | 0.80 | [kg Cu/Kg CuO] | Stoichiometry |

| Pure Cu in 50-kg bag | 5.68 | [kg Cu/bag] | |

| Worker hours per kg Cu | 1.97 | [h/kg Cu] | |

| Hours per unit process | 1.57 | [h] | |

| % time of finished product | 2.3 | % | Therefore, the UPR is 2. See Table 6 |

| Mining/Chile | Value | Unit | Source/Comment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total time to finish product | 70 | [h/finished product] | |

| Mass copper in product | 16 | [kg Cu] | |

| Proportion provenance | 0.95 | [kg Cu CL/kg Cu] | Assumption |

| Mass in unit process | 15.2 | [kg Cu] | |

| Mine production | 265,597 | [metric ton] | Production of 2016 [47] |

| Number of workers | 10,000 | [pers] | [48] |

| Hours per week | 45 | [h/week] | [49] |

| Weeks per year | 46.6 | [week/a] | [49] |

| Worker hours per kg Cu | 0.79 | [h/kg Cu] | |

| Hours per unit process | 1.2 | [h] | |

| % time of finished product | 1.7 | % | Therefore, the UPR is 2. See Table 6 |

| Processing/Turkey | Value | Unit | Source/Comment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total time to finish product | 70 | [h/finished product] | |

| Mass copper in product | 16 | [kg Cu] | |

| Proportion provenance | 1 | [kg Cu TR/kg Cu] | Assumption |

| Mass in unit process | 16 | [kg Cu] | |

| Machine processing capacity | 1300 | [kg Cu/h] | [50] |

| Number of workers | 1 | [pers/machine] | |

| Worker hours per kg Cu | 0.001 | [h/kg Cu] | |

| Hours per unit process | 0.012 | [h] | |

| % time of finished product | 0.02 | % | Therefore, the UPR is 1. See Table 6 |

| Unit Process Relevance | |

|---|---|

| 0 to 1% | 1 |

| 1 to 5% | 2 |

| 5 to 10% | 3 |

| 10% upwards | 4 |

| Subcategory | Evaluation of Switzerland | Performance Reference Point Levels |

|---|---|---|

| Delocalisation and Migration | The federal law on strangers [59] defines the admission (Art. 3) and the integration (Art. 4) of immigrant workers. What is decisive for admission is the interest of the national economy, whereby it is explicitly stated that sustainable integration and the social environment are crucial aspects. Moreover, Art. 4 states that the goal of the integration is the cohabitation of local and migrant populations based on the values of the federal constitution and reciprocal respect and tolerance | −2 There is a law on immigration, but it does not really promote integration −1 There is a law, it promotes integration, but it does not seem to be enforceable 0 There is a law, it promotes integration and it seems to be enforceable |

| Access to Material Resources | 100% of population (urban, rural and total) with access to improved sanitation facilities [29] | −2 < 25% −1 > 25% < 75% 0 > 75% |

| Child Labour | Art. 30 of the law on labour [59] prohibits the employment of people before their 15th birthday with reservations defined in paragraphs 2 and 3 | −2 The law does not protect children from working −1 The law protects children from working, but it does not seem to be enforceable 0 There is a law to protect children from working and it seems to be enforceable |

| Forced Labour | Art. 4 of the European Convention of Human Rights prohibits slavery, servitude and forced labour [60] | −2 No convention which prohibits slavery and forced labour has been signed/ratified −1 A convention has been signed/ratified, but it does not seem to be enforceable 0 A convention has been signed/ratified and it seems to be enforceable |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lobsiger-Kägi, E.; López, L.; Kuehn, T.; Roth, R.; Carabias, V.; Zipper, C. Social Life Cycle Assessment: Specific Approach and Case Study for Switzerland. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4382. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10124382

Lobsiger-Kägi E, López L, Kuehn T, Roth R, Carabias V, Zipper C. Social Life Cycle Assessment: Specific Approach and Case Study for Switzerland. Sustainability. 2018; 10(12):4382. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10124382

Chicago/Turabian StyleLobsiger-Kägi, Evelyn, Luis López, Tobias Kuehn, Raoul Roth, Vicente Carabias, and Christian Zipper. 2018. "Social Life Cycle Assessment: Specific Approach and Case Study for Switzerland" Sustainability 10, no. 12: 4382. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10124382

APA StyleLobsiger-Kägi, E., López, L., Kuehn, T., Roth, R., Carabias, V., & Zipper, C. (2018). Social Life Cycle Assessment: Specific Approach and Case Study for Switzerland. Sustainability, 10(12), 4382. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10124382