Abstract

The budget for disaster and safety management can be characterized as a large-scale public asset in which the government has a significant role. However, this budget has been managed in a somewhat scattered and inconsistent manner by different government ministries, until the Sewol ferry incident in Korea 2014. After the Sewol incident, the Ministry of Public Safety and Security has introduced a prior consultation system for budget allocation in the field of disaster and safety management, so that the budget can be reviewed in a holistic manner, effectively managed, and invested according to agreeable priorities. This study introduces the prior consultation system for the budget in disaster and safety management, which has been implemented since 2015, analyzes budget allocation procedures, and provides possible solutions to improve the current status of the prior consultation system for classification and prioritization. (1) The issues that were found in the budget plans for the fiscal years of 2016 to 2017 are, firstly, unclear classification criteria that made it hard to differentiate much more disaster-related programs and projects from less-related ones. Secondly, investment priorities of projects and programs for disaster and safety management are controversial, due to the lack of objective standards and procedures. To firmly settle down the prior consultation system, several possible solutions to these two main issues are suggested. (2) To improve actual budget classification, the current classification system needs to be reviewed at first, and social issues will be analyzed to be included as a criterion and, finally, authors will propose additional criteria and items based on the Disaster and Safety Management Framework Act. In order to improve prioritization procedures for budget allocation, disaster damage and loss are compiled to find implications and other related prioritization practices, such as prioritization in natural disaster-prone area improvement programs, which need to be analyzed to provide suggestions on improvement in prioritization. Through the proposed improvement of the classification system, projects that are not related to disaster safety are not included in the disaster safety project. Projects that are deeply related to disaster safety can be further explored. It is also recommended that an investment direction be established in consideration of damage characteristics through the investment priority improvement plan, and that qualitative assessment criteria should be considered in the criteria for similar projects, and weights should be required. The improvement measures derived can be used as follows: the scale can be clearly identified by clarifying the subject of the disaster safety budget. This gives a sense of where investment is lacking, and where it is sufficient. Investment priority is reviewed in a variety of ways, preventing budgetary bias in advance. As a result, these two improvements enable efficient operation of the disaster safety budget.

1. Introduction

The Sewol Ferry Disaster in 2014 led to emphasis on the importance of and expertise in disaster and safety management. The Ministry of Public Administration and Security (former Ministry of Public Safety and Security) has supported the budget procurement required for disaster and safety management for each ministry and relevant organization through the prior consultation system of disaster and safety budgets under Article 10-2 of the Disaster and Safety Management Framework Act. The budget for disaster and safety management refers to the one invested in projects and policies, managed under each ministry and relevant organization in relation to items included as disasters under the Disaster and Safety Management Framework Act. Through a prior consultation review of the budget for disaster and safety management for making decisions regarding investment priorities, the Korean government is aiming at enhancement of the investment efficiency of disaster and safety management projects.

Review of the Literature on Budgeting for Safety and Disaster Management

The budget for disaster and safety projects is in a field with strong public goods characteristics. The state plays a pivotal role, and a large public financial instrument is invested. The amount of the budget for disaster and safety management is also limited and, thus, requires planned operations that consider investment priorities and appropriateness when implementing projects.

The previous studies into disaster- and safety-related policies are relatively insufficient. Among them, the research concerning the budget for disaster and safety was related to the policy and institutional aspects of disaster management, and to determine the priority of investment on how to manage and share a limited budget. A key discussion at the UN Conference on Mitigation of Accident Risk in Sendai, Japan, in 2016, identified that one of the issues was the establishment of an integrated disaster management governance system for disaster risk management [1]

Sperling & Szekely (2010) [2] analyzed the lsidore Hurricane in Mexico, and pointed out that the establishment of an effective national disaster management system required an integrated disaster response. It also stressed the need to facilitate communication and build an institutional framework. It was suggested that financial resources should be provided with a stable arrangement, and the system should be operated by sharing information. Meissner et al. (2002) [3] suggested that IT technologies could significantly increase the effectiveness and effectiveness of disaster response and utilized the information management mechanisms for the response and recovery of disasters.

Cejun Cao et al. (2017) [4] stated that an integrated framework, including several elements for the effective disaster response, is needed. Donahue and Joyce (2001) [5] have reviewed alternatives for reforming disaster-related budgetary structures, and clarified criteria for determining crisis situations. Marvin and Charlotte (2010) [6] argue that it is necessary to overcome obstacles that make it difficult to establish preventive budgets. They pointed out that budgets for disaster prevention do exist, but information on their effectiveness is not sufficient.

Choi Seong-eun (2014) [7] has criticized the disaster and safety budget for not being managed in a holistic way. Choi has suggested that, for a comprehensive management method, a work scope and budget estimation of the disaster and safety sector should be conducted, evaluation of disaster prevention projects should be enhanced and, finally, it is required for the local government to improve autonomy and accountability of relevant expenditure.

Lee (2012) [8] analyzed the disaster management budget process for local government from the rent-seeking theory. Local governments were more likely to depend on the central government budget because their performance and expectations for disaster management services were mismatched.

The other is research related to the prioritization of projects implemented by budget for disaster and safety management, which has only been conducted in some specific projects or cases.

Research related to investment prioritization is mainly studied by cost–benefit analysis. The studies include a preliminary feasibility assessment of reclaimed land systems in response to floods by Mechler [9,10], the disaster mitigation project effects of the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) [11], and the Four Rivers Restoration Project by Lee [12]. Also, other studies include post-evaluation of flood control in China for the past 40 years by Benson [13], mangrove planting project in Vietnam to protect coastal residents from typhoons and storms by the International Federation of the Red Cross (IFRC), of a disaster prevention and preparedness program by Venton and Venton [14], and the effects of investment in Korea’s disaster prevention by the National Emergency Management Agency (NEMA) [15]. Specifically, Mechler and Venton used the internal rate of return (IRR) and net present value (NPV) along with the cost- benefit ratio.

Besides, Yang Ki-geun and Lee Dong-gyu (2010) [16,17] have attempted to derive policy priorities to build a more efficient program for making restoration policies for disaster-affected areas. An AHP (analytic hierarchy process) investigation was conducted on the 2007 oil spill accident in Taean. As a result, it was concluded that the restoration policy of disaster-affected areas should be carefully designed based on the viewpoints of the quality of life of local residents, and the strengthening of local competitiveness. Yang Kyung-geun (2013) [15,18] measured the priority of the foot-and-mouth disease management policy, and suggested that policy priority should be placed on prevention and preparedness, rather than on restoration and rehabilitation.

The investment priority criteria can be improved by AHP analysis. AHP can be allocated weight between investment priority criteria. Most of them already have criteria. However, damage types and projects of disaster and safety budgets should be considered preferentially, establishing criteria that could be commonly applied.

Based on the research outlined above (Choi Seong-eun, Yang Ki-geun, and Lee Dong-gyu) the research for budget in disaster and safety management needs to be designed and operated in a holistic and systematic way, and the standards for investment prioritization are needed to review its effectiveness.

Investment priority criteria have been carried out in some limited research related to specific cases. There were not studies for all types, such as natural disaster, social disaster, safety management. It was very difficult to consider because it took into consideration all types of characteristics. Other additional research is needed to comprehensively review the investment direction and priority of a disaster safety budget.

Prior consultation on the budget allocation for disaster and safety management has recently been under review for the 2017 disaster and safety budgets (plans), but enforcing them requires improving the budget classification and investment priority selection criteria.

In this article, modification and supplementary items were drawn up through the current prior consultation, at first, and secondly, recent social issues and reviews of basic laws have been added to identify additional items and, finally, the authors suggest ways to improve the classification system. Through the analysis of current damage status from natural and man-made accidents, and selection criteria of similar priority investments, suggestions will be provided to improve the selection of investment priorities for the budget allocation in disaster and safety management.

This information provides a picture of the overall size of the disaster safety budget. Hence, we can see where and how it is being invested. We can see where the budget falls short, and where it needs to be concentrated. Also, the direction and scale of investment can be identified through integrated management of the disaster safety budget. Thus, integrated management would enable the distribution of the budget and provide a clear blueprint for disaster management. Before, each ministry was carrying out a budget plan. Therefore, the disaster safety budget was not systematically managed.

The goal of this study is to offer a framework for the following goal: “the investment efficiency of projects for disaster and safety management in the Republic of Korea will be improved by stable setup of the prior consultation system for the budget allocation in the field”.

2. Current Status of the Prior Consultation System for Disaster and Safety Management

2.1. Background

Over the past five years, more than 8000 deaths and missing person incidents have occurred annually, due to various natural and social disasters and accidents, and natural disasters on their own generated an annual average of 530 billion Korean won in damages. Furthermore, in the case of damage from storms and floods, 1.487 trillion Korean won, in average annual restoration expenditures, were incurred during the last 10 years. The cost of restoring rivers and streams has been the greatest: 53.8% of all the expenses. In the case of social disasters, the number of incidents and the frequency of disaster and safety accidents, such as the Sewol Ferry Disaster and Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) are increasing in recent years, leading to massive damage. Even in the case of accidents, there has been an annual average of 21,000 deaths, and more than 430,000 injuries in the last five years, including traffic, workplace, and food safety accidents. Damage by disasters and accidents need national disaster management measures beyond individual responses, because of their impact and unpredictability.

The disaster and safety management system of the Republic of Korea maintains a large framework for managing various matters, such as natural and social disasters. However, the system has been gradually changing based on social and environmental changes. The Sewol Ferry Disaster in 2014 led to an emphasis on the importance of, and expertise in, disaster and safety management. At the national level, holistic and systematic management and policy changes have been requested to avoid the same social disasters. Thus, the government has made it possible to carry out the overall coordination function of national disaster management through the establishment of the Ministry of Public Safety and Security. National security innovation systems were established, including the “Basic Direction for Strengthening the Role of Science and Technology in Disaster Response (14.6′)”, “Effective Disaster Response Using Science and Technology (14.12′)”, “3-Year Action Strategy to Enhance Disaster Response by Science and Technology (14.12′)”, “Safety Innovation Master Plan (15.3′)”, and “10-Year Roadmap for Disaster Science and Technology Development (15.5′)”.

In addition, the overall adjustment of operations and management of budgets related to disaster and safety is being requested at the national level. For integrated management of the disaster and safety budget, priority should be given to understanding the amount and content of the related budget. Through an understanding of the overall scale of the budget for disaster and safety management, it is possible to establish a standard for allocation of the budget in the field considering urgency and efficiency. However, the only material that can be referred to is the public order, classified as the budget for disaster and safety management in the analysis of the national financial management plan. The budget for disaster and safety management, here, covers only a part of the budget, and does not cover the related issues as a whole. Thus, comprehensive disaster management is difficult from the current guideline of national disaster management.

Until 2015, the disaster safety budget had not been totally managed. This makes it difficult to define the entire budget size. This makes it difficult to determine the budget investment direction and features. With the given situation, we cannot know where and how the budget was invested, what is lacking and where the budget should be intensively invested. For instance, if an earthquake has occurred, we want to know how much budget was invested to control the earthquake. If the disaster safety budget is not totally managed, however, we cannot know the size of budget allocated for earthquake control. In other words, this makes it difficult to present the investment direction and the mid- and long-term budget blueprint in the earthquake category.

Further, we have no government expenditure classification system that is suitable for the definition of South Korea’s disaster safety budget and, yet, that enables an international comparison. There is only the classification of the functions of government (COFOG), which was developed by OECD, with the aim of analyzing the government expenditure and the aim of conducting an international budget comparison, and this enables an indirect comparison of the disaster safety budget between nations. The OECD COFOG statistics is used as the government expenditure classification in developed nations, and “public order, safety” is one of such budget items. The “public order, safety” is comprised of police, firefighting, court of law, correction, R&D, and others, of which firefighting, R&D, and others (part thereof) are seen as the disaster safety management category. However, the “public order, safety” budget fails to include the disaster safety management-related budget of government ministers, except the agencies responsible for public order and safety. Thus, if, through COFOG statistics, the “public order, safety” budget is compared between nations, the result, in a strict sense, cannot be seen as the comparison of the disaster safety budget between nations. South Korea does not offer a total disaster safety budget management system, such as the prior consultation system for the disaster safety budget. This study is very important, as it is an attempt at total budget management in the disaster safety category.

In order to solve these problems and to adjust the overall budget allocation in the field, the government selected the overall management and improvement system for safety management in each sector and sectoral policy as the tool of “Safety Innovation Master Plan” (15.3′). A basic plan has been adopted to establish a comprehensive management and improvement system for the projects by budget in disaster and safety management, which is being distributed to each institution through the “Preliminary Consultation for Budget in Disaster and Safety Management (Article 10-2 of the Disaster and Safety Management Framework Act)”. Its purpose is to improve the investment efficiency of projects in disaster and safety management by reviewing priorities of the budget allocation for disaster and safety management through prior consultation.

2.2. Enforcement Procedures and Classification System

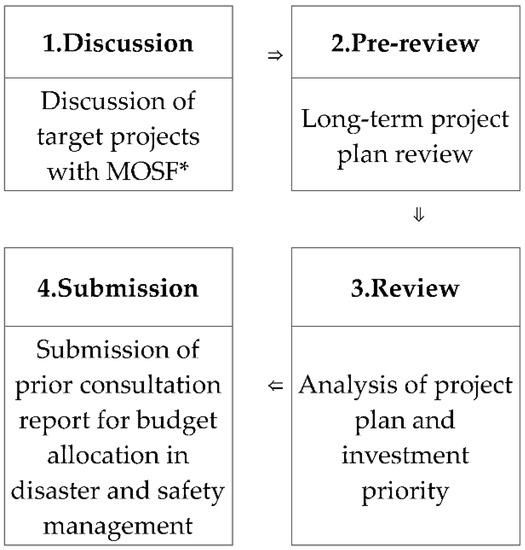

The prior consultation system for the budget allocation in the disaster and safety management consists of four steps: first, consultation on the projects for disaster and safety management subject to prior consultation; second, review of mid-term plans and investment priorities of projects in disaster and safety management by each ministry; third, review of budget according to projects in disaster and safety management requested by each ministry; fourth, confirmation for result of prior consultation (draft) and submission to the Ministry of Strategy and Finance (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Prior consultation process for budget allocation in disaster and safety management. * MOSF (Ministry of Strategy and Finance).

The classification system for project in disaster and safety management by damage is based on Article 3 (Definition) of the Disaster and Safety Management Framework Act and Classification of National Security Management Basic Plan (Natural Disaster Management Measures, Social Disaster Management Measures, and Safety Management Measures), which is the highest plan that sets the basic direction of disaster and safety management. The selection of projects is confirmed through consultation with the Ministry of Strategy and Finance.

The classification system for disaster and accident may be slightly different in the settings according to the objective. This system is classified for the purpose of prior consultation for the budget allocation in disaster and safety management. In addition to the primary purpose of disaster and safety management, the financial mobilization of the budget cannot be ruled out, so there may be some differences from the general classification system. Thus, reserve funds and grant tax correspond to the budget in disaster and safety management, but it cannot be classified into a specific type because it is a reserve budget for the preliminary restoration aspect, regardless of the damage type. In the 2017 budget (plan), nine types of natural disasters, 22 types of social disasters, and 18 types of safety management were classified. As mentioned above, since the reserve budget and grant taxes cannot be included in the three classification systems, they were separated (Table 1).

Table 1.

Budget and number of project by disaster types (USD million).

The disaster safety budget for 2017 accounts for approximately 3.5% of the total national budget of 400.7 trillion won. By disaster types, the value of damages is approximately natural disaster—4.7 trillion, social disaster—3.7 trillion, safety management—3.0 trillion, and others—2.8 trillion. In particular, the investment scale decreased significantly despite damages caused by flooding, workspace accidents, marine disaster and livestock infectious.

In the process of classifying projects in disaster and safety management, it is difficult, but very important, to determine the relevance of a project with the level of disaster and safety management. Therefore, except for the projects with little relevance to the level of disaster and safety through the improvement of the classification system, it is necessary to find out additional appropriate projects that are not yet included in the budget for disaster and safety management.

2.3. Direction for Budget Allocation in Disaster and Safety Management in 2017

The budget demand related to the project in disaster and safety management in 2017 was, in total, 13.8 trillion won, accounting for 83% of the top-five ministries, including 26.9% in the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport; 16.0% in the Ministry of Public Safety and Security; 14.2% in the Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs; and 11.0% in the Ministry of Strategy and Finance.

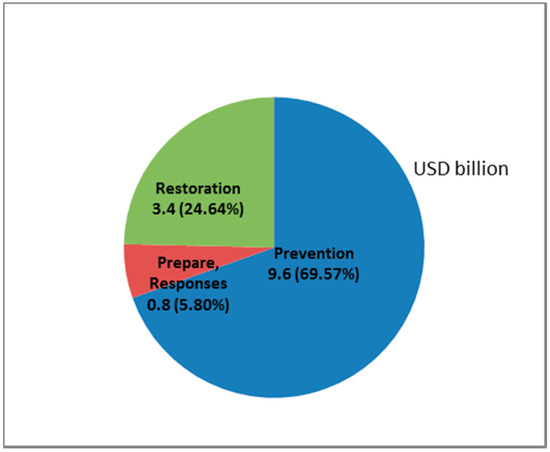

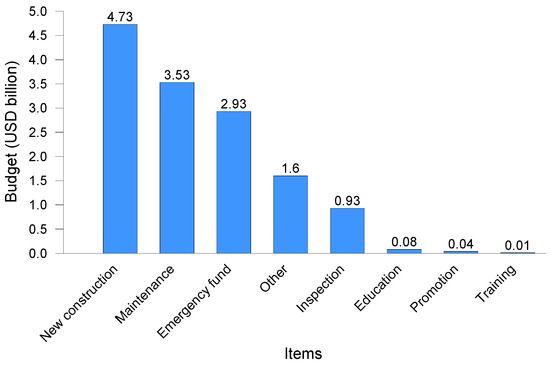

By damage type, damage from storms and floods was 3.8 trillion Korean won (27.7%); reserve fund and grant tax, 2.7 trillion Korean won (19.1%); traffic accidents, 1.5 trillion Korean won (11.2%); and railway traffic accidents, 0.9 trillion Korean won. In terms of investment stage, 9.6 trillion Korean won (69.5%) was for prevention, 0.8 trillion Korean won (6.0%) for preparation and response, and 3.4 trillion Korean won (24.6%) for restoration. When classified by investment items, facilities, equipment, and system construction and upgrading that directly affect damage reduction, occupy the largest portion, followed by maintenance and operation. By contrast, the proportion of investment related to education, training, and public relations is relatively low (Figure 2 and Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Draft budget allocation by phases for FY 2017

Figure 3.

Itemized draft budget for FY 2017.

2.4. Method of Reviewing Investment Priorities

In the prior consultation for the 2017 budget in disaster and safety management, the following criteria are applied for reviewing investment priorities. In general, damage reduction, which is the main objective of projects in disaster and safety management, and the main and long-term budget are considered; items that applied to both, by damage type and project type, were selected and reviewed (Table 2).

Table 2.

Investment priority criteria for FY 2017.

In the case of human losses and physical damage, the analysis focused mainly on the quantitatively estimated human losses, property damage, and other damage that occurred in the last five years. In the case of major past damage, maximum damage cases of the type at home and abroad were examined.

Through a review of investment priorities, 28 types of investment were selected as the most important ones according to the 50 damage types based on human losses and physical damage. Among the 348 businesses, 169 projects with high damage mitigation effectiveness, in terms of damage type, were deemed necessary to expand from the investment level in 2016.

Major projects that need to expand in terms of investment are as follows: (1) strengthening and expanding drought and flood prevention facilities to prevent large-scale natural disasters and projects that establish and expand abnormal climate and yellow dust measurement systems; (2) establishing and strengthening monitoring/upgrade systems for strengthening social response capabilities, enhancement of specialized equipment/facilities, and projects that support continuous response training; and (3) national safety education to prevent accidents caused by carelessness and projects that strengthen safety facilities for roads and workplaces where there are frequent accidents.

From a financial point of view, it is desirable to review investment preferences by focusing on items that are commonly applied to all types of damage and business, and suggest investment directions.

However, it is difficult to apply the same standard because each type of damage is different from the viewpoint of characteristics of disaster and accidents.

Therefore, when investment priorities are being reviewed, it is necessary to establish criteria for the selection of key investment directions considering the characteristics and effects of disaster and accidents for each type and project.

3. Material and Methods

Based on the problems as discussed above, two aspects of the improvement plan of prior consultation system for budget allocation in disaster and safety management are presented: the classification standard and the investment priority review criteria.

The classification system improvement measures were presented through the survey and analysis of the existing data. The classification criteria improvement measures had many limitations. Since the disaster safety-related classification system is directly related to budget, the policy and financial features cannot be excluded. In addition, unavailability of comparable data made it difficult to present the improvement measures. Despite these limitations, this study examines the existing classification system, related laws, and recent issues, so as to present the improvement measures. The need for the improvement of classification system is recognized, but the reference data for the disaster safety budget classification system, in a strict sense, have not been available.

The investment prioritization improvement measures are more sensitive. The existing method designed for evaluating the investment priority uses different models by type of investment, so such problems of lack of data are not created, but since the evaluation of investment priority in the disaster safety project targets all projects and, thus, requires relative evaluation, the available data are lacking. This study presented the investment prioritization improvement measures so that the available data can cover all types of data, if possible, and can be objective.

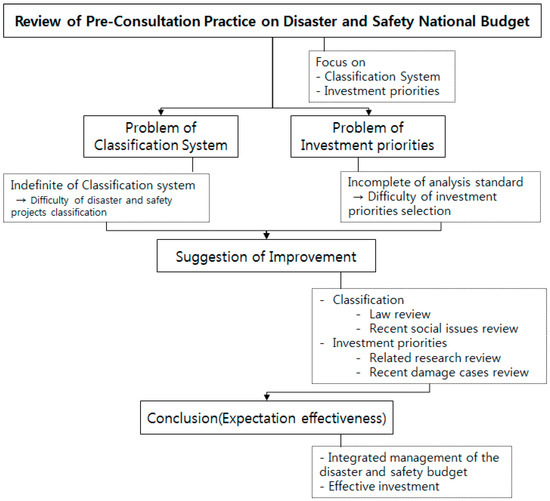

Figure 4 shows the process and method of the original sphere. The aim of this study is to provide an improvement plan for the disaster safety budget. It is important to establish classification schemes and investment priority standards. The problem with classification and investment priorities is ambiguity and imperfection. The ambiguity of the classification system has taken into consideration the law review and recent social issues. Imperfection of investment priorities was considered in the relevant study and in the recent damage case reviews.

Figure 4.

Analysis process and methods introduced by this study.

3.1. Improvement Plan for the Classification Criteria

The problem with the classification system is that it is not clear what the classification criteria are. Disaster and safety laws and recent social issues have been reviewed to improve the classification system. The Act provides a basis for identifying disaster safety and, also, allows consideration of the criteria for policy judgment. Recent social issues may add types not currently classified as disaster and safety budgets.

In order to improve the classification standard, the authors suggest (1) to draw up revision/supplementation items through the revision of the 2017 classification standard; (2) to consider the recent social issues; and (3) to discover additional items through the review of the Disaster and Safety Management Framework Act. The classification standard for consultation on budget in the disaster and safety management can be improved by employing the suggestions above.

The main items modified and supplemented under the 2017 classification standard were selected to improve the previously examined problems. Recent social issues have been reviewed, focusing on the comprehensive analysis and forecasting of disaster and accident situation, and based on the weekly safety incident forecast data (Ministry of Public Safety and Security 1 January 2015~31 July 2016). Types that became issues through media coverage were added.

The following are the main modifications and supplements to the 2017 classification standard. First, it is necessary to add damage that is not specified in the classification standard, even though it is a similar type of damage. Second, a combination is required if the damage type is similar. Third, there are cases in which it is necessary to change the name of the damage type.

In the case of recent social issues, safety regulations and management were mentioned most frequently, followed by forest fires, fires, large-scale fires, electric- and gas-safety management, heat waves, cold waves, water leisure activities, collapses, floods, yellow dust, and marine accidents (Table 3). Lastly, basic laws on disaster and safety management were reviewed, and items such as tidal occurrences and environmental pollution accidents were added.

Table 3.

Social issues on disaster and safety management.

Based on the above, methods for improving classification criteria for each type were suggested as follows.

In general, the damage types with a greater ratio compared to other types need to be further categorized. They are not classified as a damage type, but need additional identification considering social issues and the recent damage situation. In addition, similar damage types need to be modified and supplemented in cases in which a combination is needed, and the name of the damage type needs to be changed.

Classified by type, first, 74 projects addressed flood hazards out of total 348 (about 21%) in terms of natural disaster, and these should be further categorized. In the case of storms and floods, they include many disasters, such as typhoons, floods, heavy rain, strong winds, storm surges, etc.; compared to other disasters, the number of target projects is large.

Projects conducted in 2017 can be largely categorized into inland flood prevention projects, including urban flood response, reservoir installation, and improving disaster risk areas, and coastal harbor projects, such as building harbor facilities, marine and water resources management, and national fishery port management. Therefore, further categorization is possible. Fine dust is an item not included in the classification standard of disaster and accident, but it needs to be added because, recently, it has shown a high risk of causing damage. In addition, heat waves are not included in natural disasters. However, given recent social issues, it is necessary to add them, considering seasonal disasters, such as heavy snow/cold waves.

Second, social disasters are mentioned under social issues and basic law, but it is necessary to add items that have not been classified yet. In other words, it is necessary to prevent disasters and accidents from being omitted by including explosions; environmental pollution; energy; financial accidents; and chemical, biological, and radiological accidents. Third, safety management must include with water leisure activities, electric accidents, gas accidents, and other similar incidents. Furthermore, family, sexual, and school violence must be changed to criminal offenses against public order and security that include public order and safety, and the scope must be expanded.

3.2. Improvement Plan for Investment Priority Review Criteria

The state invests in many areas for disaster safety management. Investment priorities are necessary for the efficient allocation of a limited budget. Investment priorities prevent wastage of budgets. Appropriate investment is possible in the areas where investment priorities are required.

In order to suggest ways to improve the criteria for reviewing investment priorities, the following points were analyzed, according to recent disaster safety accidents and investment priority criteria for projects in disaster and safety management.

The case of related research has something in common in terms of the nation’s public projects. By reviewing the associated study cases, an idea of existing items and criteria can be explored, and the application can be proposed as a project related to disaster and safety. Recent disaster safety accidents provide a characteristic for each damage type, and it would be possible to create appropriate investment priorities for each type.

3.2.1. Damage Status by Disaster and Accident

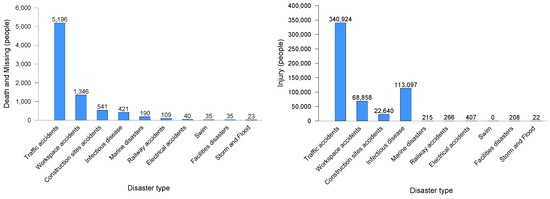

In the past five years, about 8000 deaths or missing person incidents have occurred due to various disasters and accidents (Figure 5, Table 4) [19].

Figure 5.

Annual average human losses from 2010 to 2014 [19].

Table 4.

Other damages (annual average from 2010 to 2014) [19].

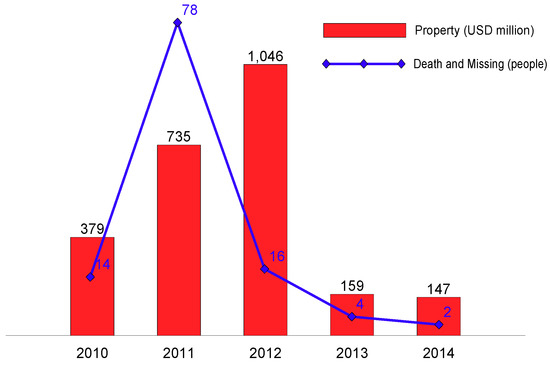

In the case of natural disasters, damage was mostly caused by floods, and the most large-scale typhoons, such as Rusa, caused major damage in the 2000s (Table 5). Recently, however, the risk of large-scale damage caused by typhoons and heavy rain due to abnormal weather has been increasing. The biggest damage in the last five years was caused by heavy rainfall and typhoons (Muifa) in July 2011, and about 78 deaths and missing person incidents occurred (Figure 6). Human losses are the number of deaths or missing persons, according to national statistics.

Table 5.

Major natural disaster damage [19].

Figure 6.

Damage by storm and flood from 2010 to 2014 [19]. Source: NEMA (2010–2014).

After 2013, no hit typhoons Korea. Thus, there were no incidents of big damages. However, recent climate changes have caused a reduction of the rainfall period and increasing of rainfall intensity. Thus, there is the possibility of large-scale damage, such as that which occurred as a result of “Rusa”.

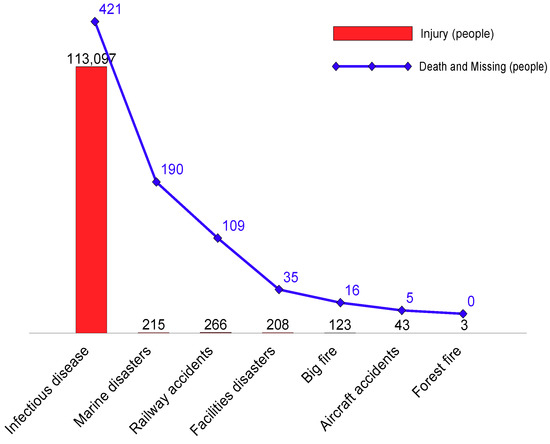

In the case of social disasters, the types of damage, such as infectious diseases, marine vessel accidents, railway accidents, disasters at facilities, large-scale fires, and explosions are complicated and varied (Figure 7), and the socio-economic ripple effect was enormous. In particular, 706,911 people were infected with the new influenza virus in 2009, and about 304 deaths and missing persons occurred during the Sewol Ferry Disaster in 2014 (Table 6). In particular, most human casualties were caused by internal factors such as personal carelessness.

Figure 7.

Annual average social disaster damage from 2010 to 2014 [19].

Table 6.

Major social disaster damages [19].

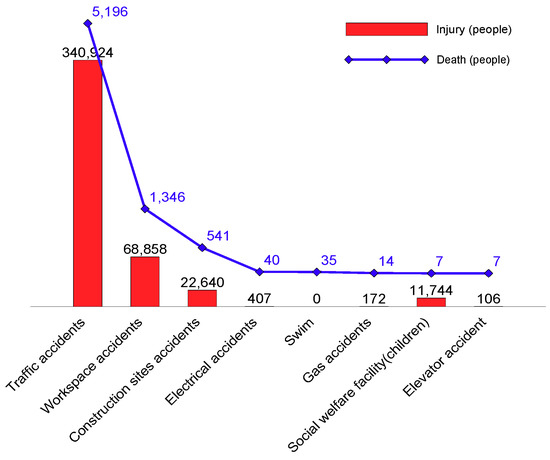

In the case of safety management, 7000 deaths and more than 440,000 injuries occur per year (Figure 8), and carelessness and negligence were the main causes in most cases. Although their economic and social impacts are less than for natural and social disasters, damage has occurred in road traffic accidents, workplace accidents, and electric and gas accidents, which are closely related to people’s lives (Table 7). The damage conditions caused by various types of accidents in Figure 7 are duplicates of the details of damage shown in Figure 4. It can be seen that most accidents in Korea are related to safety management.

Figure 8.

Annual average accident damages from 2010 to 2014 [19].

Table 7.

Major accident damages [19].

3.2.2. Criteria for Selecting Priorities for Projects in Disaster and Safety Management

The relevant projects in similar areas are considered to be related to public safety and mitigation of disasters and accidents. Table 8 shows the main features of investment priorities for each category. This stage is determined by the characteristics of each type of damage. Most disaster safety projects, at this stage, are related to the nation. As for mitigation of damages, the government, experts, and others evaluate them.

Table 8.

Main features of investment priorities in disaster and safety management.

In the case of maintenance projects on natural disaster-prone areas, damage mitigation is evaluated through quantitative and qualitative methods, and scores and ratios are assigned to each item. In the case of the collapsed hazard areas, the damage details are identified based on past damage cases, and the items are presented step by step. The environmental impact assessment items are divided into common parts and evaluation items.

3.2.3. Improvement Criteria for Investment Priority Review

Based on the abovementioned damage status by disasters and accidents, and investment priorities for disaster and safety management, the following suggestions were made to improve the priority of disaster safety project investment.

First, the criteria for reviewing investment priorities need to be classified according to each type of damage. The characteristics of each type of damage include common items, such as direct and indirect damages, which should be included as mandatory items. In addition to the common items, it is necessary to present the evaluation items according to the characteristics of each type to achieve objective, so that priority is not given only to some types and projects.

Second, it is necessary to utilize not only the recent damage situation but, also, the largest damage status in the past. Even if the current damage did not occur in a situation in which disasters and accidents in each field are becoming larger and more complex, it is necessary to prepare for the possible occurrence, and it is desirable to refer to the cases studies with the biggest damage in the past.

Third, considering that the project implemented by the budget in disaster and safety management as a project at a national level, it is necessary to consider the policy grounds, such as laws and institutions. The legal basis of the project, the ground for the plan, and the policy judgment, can prevent advance bias by subjective judgment toward the budget in certain fields, and can provide a universally valid background.

Fourth, qualitative evaluation standards that reflect the needs and demands of the public should be considered. Most of the abovementioned various criteria are quantitative evaluation criteria, and it is the most basic for an evaluation index indicating the necessity of business. However, quantitative evaluation criteria alone are not enough to show the necessity of the project, and it is necessary to provide a qualitative evaluation index considering the subjects affected by the project.

Fifth, it is essential to secure the objectivity of the evaluation criteria, and to score and weight each criterion. Objectivity is the most important criterion, and it is necessary to revise and supplement the criterion by gathering opinions from experts, personnel, and institutions. In addition, an analysis is needed to assign scores and weights to the evaluation items, in order to prioritize the criteria.

4. Conclusions

This study was carried out to suggest the plan for an improved system for the prior consultation system for budget allocation in disaster and safety management. In this study, the problems of the disaster safety budget consultation system were considered unclear in the classification system, and there was a non-establishment of investment priority criteria. This study proposed measures to establish a classification system for projects subject to the disaster safety budget consultation, and recommendations for criteria for selecting investment priority.

The variables and methods utilized are as follows. To present improvements in the classification system and investment priority, the system and detailed contents of prior consultation were reviewed, and problems were derived from the analysis. In the case of the classification system for the budget in disaster and safety management, a basic framework was established in the classification standard of 2017, but it was suggested that modification and supplementation is necessary, considering the relevance of disaster and accidents. Recently, social issues and “Basic law on disaster and safety management” have been used to suggest revisions and additional items. In the criteria for reviewing investment priorities, it is mentioned that the common standard is applied, even though the damage characteristics are different for each type of damage. In order to improve prior consultation process for budget in the field, first, investment priority review criteria should be classified according to the characteristics of damage type. Second, it is not only the recent damage situation that should be analyzed but, also, the case studies of biggest damage in the past. Third, policy criteria, such as laws and regulations, should be considered. Fourth, we need to consider qualitative evaluation criteria that reflect national needs and demands and, finally, we need to conduct research, analysis, and build a standard to ensure objectivity of evaluation criteria.

The improvement measures derived can be used as follows: although the classification system is not currently classified as a damage type, it was discovered by considering social issues and recent damage conditions, such as fine dust and heatwaves. It was recommended that the investment priority criteria should consider the recent damage characteristics, and that the qualitative assessment standards and criteria should be weighted based on the review criteria of similar projects.

The improvement measures derived can be used as follows: the scale can be clearly identified by clarifying the subject of the disaster safety budget. This gives a sense of where investment is lacking, and where it is sufficient. Investment priority is reviewed in a variety of ways, preventing budgetary bias in advance. As a result, these two improvements enable efficient operation of the disaster safety budget.

Policymakers can correct incorrect budget execution, properly scale the budget for each type of damage, and prevent wasted budgets. In addition, by providing criteria for investment priority to stakeholders, they may refer to requests for type or business review.

This study recognized many limitations in presenting the disaster safety budget classification system and improvement measures. First, with similar systems not existing, reference data are unavailable. The existing studies analyzed related systems, derived implications, and used them in presenting their improved measures. Our study, for the presentation of the classification system improvement measures, surveyed related laws and recent social issues. We checked if the contents are included in related laws, but they are missing, and we surveyed the recent social issues to explore where to invest the disaster safety budget. The disaster safety budget classification system and investment prioritization are so sensitive as to reflect policy and financial aspects. This means that, even though there are problems, much time may be required to prepare improvement measures and to apply them to the reality. Nonetheless, in order to allow this system to continue to be maintained, we have to analyze the yearly prior consultation system and to determine its problems. Although our study has many limitations, we have endeavored to resolve them. Our study can be used as data to present yet another series of improvement measures.

The prior consultation system for the budget allocation in disaster and safety management was established just several years ago, and the system is still currently being established through revision and supplementation. In particular, it is very difficult to establish a comprehensive standard in the sense that it covers the whole project implemented by the budget in disaster and safety management. This study is meaningful in that the budget in the field after the Sewol Ferry disaster is operated and managed through a professional system, and in that it suggests ways to improve for more effective operation. It is expected that efficient and objective preliminary consultation will be possible by the improvement of the classification system of projects in disaster and safety management, and reviewing standards for investment priority review. This can contribute to the reduction of damage caused by disasters and accidents, thereby contributing to the creation of a safe human environment.

Author Contributions

B.-Y.H. proposed the topic of this study and wrote the paper, while J.-H.P. and W.-H.H. performed the simulations and analyzed the data.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- United Nations. Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030. In Proceedings of the World Conference on Disaster Risk Reductio, Sendai, Japan, 18 March 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Sperling, F.; Szekely, F. Disaster Risk Management in a Changing Climate. In Proceedings of the World Conference on Disaster Reduction, Kobe, Japan, 18–22 January 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Meissner, A.; Luckenbach, T.; Risse, T.; Kirste, T.; Kirchner, H. Design Challenges for an Integrated Disaster Management Communication and Information System. In Proceedings of the First IEEE Workshop on Disaster Recovery Networks (DIREN 2002), Co-Located with IEEE INFOCOM, New York, NY, USA, 24 June 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, C.; Li, C.; Yang, Q.; Zhang, F. Multi-Objective Optimization Model of Emergency Organization Allocation for Sustainable Disaster Supply Chain. Sustainability 2017, 11, 2103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donahue, A.K.; Philip, G.J. A Framework for Analyzing Emergency Management with an Application to Federal Budgeting. Public Adm. Rev. 2001, 61, 728–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marvin, P.; Charlotte, K. Budgeting for Disasters: Focusing on the Good Time. OECD J. Budg. 2010, 2010/1, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, S.U. Security Budget Analysis and Effective Budgeting. J. Saf. Crisis Manag. 2014, 10, 179–203. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.H. The Rent-Seeking on Budgetary Decision-Making Process in Disaster Management of Local Government: An Expectation Disconfirmation Approach; Journal of Contents: Seoul, Korea, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Mechler, R. Cost-Benefit Analysis of Natural Disaster Risk Management in Developing and Emerging Countries; Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development: Bonn, Germany, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Mechler, R. Semarang Case Study; Interim Report for GTZ; Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development: Bonn, Germany, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- FEMA (Federal Emergency Management Agency). FY 2006 Pre-Disaster Mitigation Program—Guidance; FEMA: Cleveland, OH, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.W. Economic Implications of 4 Great Rivers Revitalization Project; Korea Water Resources Association: Seoul, Korea, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- IFRC (International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent). World Disasters Report 2002; IFRC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Venton, C.; Venton, P. Disaster Preparedness Programmes in India: A Cost Benefit Analysis; Humanitarian Practice Network: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- National Emergency Management. A Study on the Research for the Method to Strengthen the Disaster Mitigation Activities and to Increase the Investments; National Emergency Management: Sejong-si, Korea, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- KIPA (Korea Institute of Public Administration). A Study on the Improvement of Budget Allocated to Disaster Safety Management; KIPA: Seoul, Korea, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, G.G.; Lee, D.G. A Study on Relative Importance and Priority Analysis of Community Resilience Strategy in the Damaged District; Journal of Contents: Seoul, Korea, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, G.G. Analysis of Relative Importance of FMD Disaster Management Policies by their Categories—Focused on the Privatization Using AHP Method; Journal of Contents: Seoul, Korea, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- NEMA (National Emergency Management Agency). Annual Disaster Report; NEMA: Seoul, Korea, 2010–2014. [Google Scholar]

- NEMA (National Emergency Management Agency). Guideline of Disaster Management Project on Hazard Area; NEMA: Seoul, Korea, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- NDMI (National Disaster Management Institute). Effect Analysis and Development Plan for the Maintenance Project on Natural Disaster Prone Areas; NDMI: Ulsan, Korea, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- NDMI (National Disaster Management Institute). Improvement in the Determination of the Investment Priority for Collapse Hazard Areas; NDMI: Ulsan, Korea, 2011. [Google Scholar]

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).