Exploring the Effect of Different Performance Appraisal Purposes on Miners’ Organizational Citizenship Behavior: The Mediating Role of Organization Identification

Abstract

1. Introduction

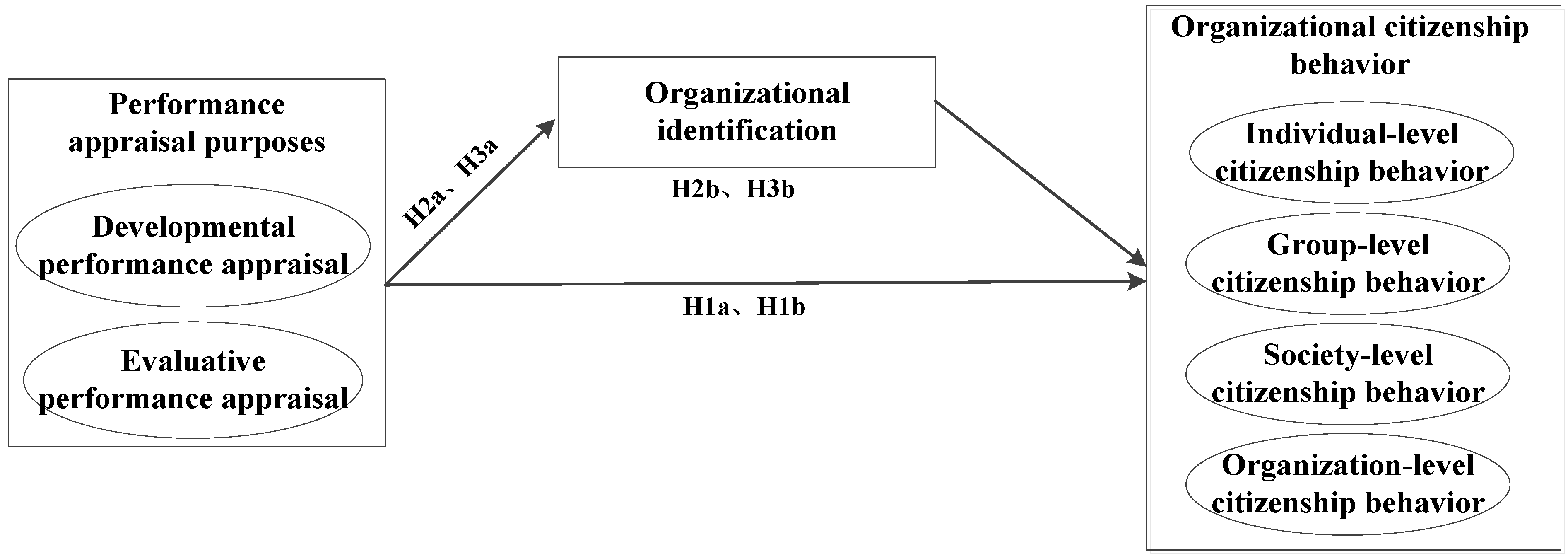

1.1. The Performance Appraisal Purpose and OCB

1.2. The Mediating Effect of Organizational Identification on the Relationship between Performance Appraisal Purposes and OCB

2. Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Independent Variables (Performance Appraisal Purpose)

2.2.2. Mediator Variable (Organizational Identification)

2.2.3. Dependent Variables (Organizational Citizenship Behavior)

2.2.4. Control Variables

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

3.2. Regression Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. The Relationship between Performance Appraisal Purpose and OCB

4.2. The Mediating Effects of Organizational Identification

5. Implications for Research and Practice, Limitations, and Future Research

6. Conclusions

- (1)

- Both development performance appraisal and evaluative purpose of the performance appraisal significantly and positively affect overall OCB and its four dimensions. However, compared with evaluative purpose of the performance appraisal, developmental purpose of the performance appraisal has a stronger impact on overall OCB and its four dimensions. This finding indicates that miners will be motivated to perform more OCB when coal mining enterprises use performance appraisal results to help miners improve their occupational ability and promote career development.

- (2)

- Both development performance appraisal and evaluative purpose of the performance appraisal significantly and positively affect organizational identification. In addition, compared with evaluative purpose of the performance appraisal, developmental purpose of the performance appraisal has a stronger impact on organizational identification. Because miners in coal mining enterprises pay more attention to intrinsic demands such as skill upgrading than to extrinsic demands such as salary and welfare, developmental purpose of the performance appraisal is more able to meet intrinsic demands of miners compared with evaluative purpose of the performance appraisal. Consequently, developmental purpose of the performance appraisal is more likely than evaluative purpose of the performance appraisal to enhance organizational identification.

- (3)

- Organizational identification has significant and positive impacts on OCB and its four dimensions. Higher organizational identification can effectively enhance miners’ sense of responsibility for maintaining organizational interests, which motivates miners to perform more OCB.

- (4)

- Organizational identification partially mediates the effects of developmental purpose of the performance appraisal on overall OCB, as well as on individual-level, group-level, organization-level, and society-level OCB. Organizational identification partially mediates the effects of evaluative purpose of the performance appraisal on overall OCB and individual-level OCB, and completely mediates the effects of evaluative purpose of the performance appraisal on group-level, organization-level, and society-level OCB. These conclusions show that organizational identification is one of the key variables that connects miners’ performance appraisal purposes and OCB.

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- State Administration of Coal Mine Safety of China. National Conference on Production Safety. 2017. Available online: http://www.chinasafety.gov.cn/newpage/Contents/Channel_22240/2017/0116/282416/content_282416.htm (accessed on 12 March 2018).

- State Administration of Coal Mine Safety of China. 2017. Available online: http://www.chinasafety.gov.cn/newpage/Contents/Channel_22249/2017/0317/284828/content_284828.htm (accessed on 12 March 2018).

- Yin, W.; Fu, G.; Yang, C.; Jiang, Z.; Zhu, K.; Gao, Y. Fatal gas explosion accidents on Chinese coal mines and the characteristics of unsafe behaviors: 2000–2014. Saf. Sci. 2017, 92, 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Qi, H.; Long, R.; Zhang, M. Research on 10-year tendency of china coal mine accidents and the characteristics of human factors. Saf. Sci. 2012, 50, 745–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Ma, S. Application of Man–Machine–Environment System Engineering in Coal Mine Accident. In Man-Machine-Environment System Engineering; Springer: Singapore, 2016; pp. 601–608. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Qi, H.; Feng, Q. Characteristics of direct causes and human factors in major gas explosion accidents in Chinese coal mines: Case study spanning the years 1980–2010. J. Loss Prev. Process Ind. 2013, 26, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treviño, L.K.; den Nieuwenboer, N.A.; Kishgephart, J.J. (un)ethical behavior in organizations. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2014, 65, 635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paul, P.S.; Maiti, J. The role of behavioral factors on safety management in underground mines. Saf. Sci. 2007, 45, 449–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organ, D.W. Organizational Citizenship Behavior: The Good Soldier Syndrome; Lexington Books: Lexington, KY, USA, 1988; p. 56. [Google Scholar]

- Organ, D.W. Organizational citizenship behavior: It’s construct clean-up time. Hum. Perform. 1997, 10, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organ, D.W.; Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B. Organizational Citizenship Behavior: Its Nature, Antecedents, and Consequences; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Shahin, A.; Shabani Naftchali, J.; Khazaei Pool, J. Developing a model for the influence of perceived organizational climate on organizational citizenship behavior and organizational performance based on balanced score card. Int. J. Prod. Perform. Manag. 2014, 63, 290–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, T.W.H.; Feldman, D.C. Affective organizational commitment and citizenship behavior: Linear and non-linear moderating effects of organizational tenure. J. Vocat. Behav. 2011, 79, 528–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curcuruto, M.; Conchie, S.M.; Mariani, M.G.; Violante, F.S. The role of prosocial and proactive safety behaviors in predicting safety performance. Saf. Sci. 2015, 80, 317–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafa, A.M.S.; Gould-Williams, J.S. Testing the mediation effect of person–organization fit on the relationship between high performance HR practices and employee outcomes in the Egyptian public sector. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2014, 25, 276–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kehoe, R.R.; Wright, P.M. The impact of high-performance human resource practices on employees’ attitudes and behaviors. J. Manag. 2013, 39, 366–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafa, A.M.S.; Gould-Williams, J.S.; Bottomley, P. High-performance human resource practices and employee outcomes: The mediating role of public service motivation. Public Adm. Rev. 2015, 75, 747–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfes, K.; Shantz, A.D.; Truss, C.; Soane, E.C. The link between perceived human resource management practices, engagement and employee behaviour: A moderated mediation model. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2013, 24, 330–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleveland, J.N.; Murphy, K.R.; Williams, R.E. Multiple uses of performance appraisal: Prevalence and correlates. J. Appl. Psychol. 1989, 74, 130–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Wang, S.; Zhao, S. Does HRM facilitate employee creativity and organizational innovation? A study of Chinese firms. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2012, 23, 4025–4047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boswell, W.R.; Boudreau, J.W. Employee satisfaction with performance appraisals and appraisers: The role of perceived appraisal use. Hum. Resour. Dev. Q. 2000, 11, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poursafar, A.; Rajaeepour, S.; Seyadat, S.A.; Oreizi, H.R. Developmental performance appraisal and organizational citizenship behavior: Testing a mediation model. J. Educ. Pract. 2014, 5, 184–193. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, P.J.; Pierce, J.L. Effects of introducing a performance management system on employees’ subsequent attitudes and effort. Public Pers. Manag. 1999, 28, 423–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I.; Fishbein, M. Attitude-behavior relations: A theoretical analysis and review of empirical research. Psychol. Bull. 1977, 84, 888–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, H.; Turner, J.C. The Social Identity Theory of Intergroup Behavior. In Psychology of Intergroup Relations; Worchel, S., Austin, W., Eds.; Nelson Hall: Chicago, IL, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, L.Y.; Aryee, S.; Law, K.S. High-performance human resource practices, citizenship behavior, and organizational performance: A relational perspective. Acad. Manag. J. 2007, 50, 558–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foreman, P.; Whetten, D.A. Members’ identification with multiple-identity organizations. Organ. Sci. 2002, 13, 618–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y.; Kim, M.S.; Choi, J.N.; Kim, M.; Oh, W.K. Does leader-follower regulatory fit matter? The role of regulatory fit in followers’ organizational citizenship behavior. J. Manag. 2017, 43, 1211–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, C.F.; Liang, J.; Ashford, S.J.; Lee, C. Job insecurity and organizational citizenship behavior: Exploring curvilinear and moderated relationships. J. Appl. Psychol. 2015, 100, 499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.Q.; Simon, L.S.; Wang, L.; Zheng, X. To branch out or stay focused? Affective shifts differentially predict organizational citizenship behavior and task performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 2016, 101, 831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasra, M.A.; Heilbrunn, S. Transformational leadership and organizational citizenship behavior in the Arab educational system in Israel: The impact of trust and job satisfaction. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2016, 44, 380–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremblay, M.; Simard, G.; Mathlouthi, W. When Positive is Better and Negative Stronger: A study of Job Satisfaction, OCB and Absenteeism. In Academy of Management Proceedings; Academy of Management: Briarcliff Manor, NY, USA, 2016; Volume 2016, p. 10082. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, L.J.; Anderson, S.E. Job satisfaction and organizational commitment as predictors of organizational citizenship and in-role behaviors. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 601–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tziner, A.; Sharoni, G. Organizational citizenship behavior, organizational justice, job stress, and workfamily conflict: Examination of their interrelationships with respondents from a non-Western culture. Rev. Psicol. Trab. Organ. 2014, 30, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stynen, D.; Forrier, A.; Sels, L.; De Witte, H. The relationship between qualitative job insecurity and OCB: Differences across age groups. Econ. Ind. Democr. 2015, 36, 383–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chahal, H.; Mehta, S. Antecedents and consequences of organisational citizenship behaviour (OCB): A conceptual framework in reference to health care sector. J. Serv. Res. 2010, 10, 25. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Paine, J.B.; Bachrach, D.G. Organizational citizenship behaviors: A critical review of the theoretical and empirical literature and suggestions for future research. J. Manag. 2000, 26, 513–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitonga-Monga, J.; Flotman, A.; Cilliers, F.V.N. Organizational citizenship behaviour among railway employees in a developing country: Effects of age, education and tenure. South. Afr. Bus. Rev. 2017, 21, 385–406. [Google Scholar]

- Todd, S.Y.; Kent, A. Direct and Indirect Effects of Task Characteristics on Organizational Citizenship Behavior. N. Am. J. Psychol. 2006, 8, 253–268. [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan, R.; Ismail, S.; Loon, K.W.; Muthusamy, G.; Melaka, K.B. The Moderating Effect of Employee Personality in the Relationship Between Job Design Characteristics and Organizational Citizenship Behavior. Soc. Sci. 2017, 12, 1014–1023. [Google Scholar]

- Farh, J.L.; Zhong, C.B.; Organ, D.W. Organizational citizenship behavior in the People’s Republic of China. Organ. Sci. 2004, 15, 241–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somech, A.; Ron, I. Promoting organizational citizenship behavior in schools: The impact of individual and organizational characteristics. Educ. Adm. Q. 2007, 43, 38–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, U.H.; Kim, H.K.; Kim, Y.H. Determinants of organizational citizenship behavior and its outcomes. Glob. Bus. Manag. Res. 2013, 5, 54. [Google Scholar]

- Friesen, J.P.; Kay, A.C.; Eibach, R.P.; Galinsky, A.D. Seeking structure in social organization: Compensatory control and the psychological advantages of hierarchy. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2014, 106, 590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, Y.T.; Wong, C.S.; Ngo, H.Y.; Lui, H.K. Different responses to job insecurity of Chinese workers in joint ventures and state-owned enterprises. Hum. Relat. 2005, 58, 1391–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalili, A.; Khalili, A. Transformational leadership and organizational citizenship behavior: The moderating role of emotional intelligence. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2017, 38, 1004–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, L.K.; Tui, L.G. Leadership styles and organizational citizenship behavior: The mediating effect of subordinates’ competence and downward influence tactics. J. Appl. Bus. Econ. 2012, 13, 59–96. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, S.L.; Morrison, E.W. Psychological contracts and OCB: The effect of unfulfilled obligations on civic virtue behavior. J. Organ. Behav. 1995, 16, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.W.; Huang, J.T.; Niu, L.X. Evolutionary model of miners’ violation behavior based on multi-agent simulation. China Saf. Sci. J. 2013, 23, 10–15. [Google Scholar]

- Li, F.W.; Yuan, Z.Y.; Li, Y.J. Effects of work environment stressors on coalmine employees’ counter-productive work behavior and safety outcome. China Saf. Sci. J. 2012, 22, 20–26. [Google Scholar]

- Kunar, B.M.; Bhattacherjee, A.; Chau, N. Relationships of job hazards, lack of knowledge, alcohol use, health status and risk taking behavior to work injury of coal miners: A case-control study in India. J. Occup. Health 2008, 50, 236–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, X.; Zhao, X. An empirical investigation of the influence of safety climate on safety citizenship behavior in coal mine. Procedia Eng. 2011, 26, 2173–2180. [Google Scholar]

- Haybatollahi, M.; Ayim, S.G. Organizational Citizenship Behaviour: A Cross-Cultural Comparative Study on Ghanaian and Finnish Industrial Workers. Scand. J. Organ. Psychol. 2015, 7, 19–32. [Google Scholar]

- Boswell, W.R.; Boudreau, J.W. Separating the developmental and evaluative performance appraisal uses. J. Bus. Psychol. 2002, 16, 391–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cennamo, L.; Gardner, D. Generational differences in work values, outcomes and person-organisation values fit. J. Manag. Psychol. 2008, 23, 891–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lester, S.W.; Standifer, R.L.; Schultz, N.J.; Windsor, J.M. Actual versus perceived generational differences at work: An empirical examination. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2012, 19, 341–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bednall, T.C.; Sanders, K.; Runhaar, P. Stimulating informal learning activities through perceptions of performance appraisal quality and human resource management system strength: A two-wave study. Acad. Manag. Learn. Educ. 2014, 13, 45–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molm, L.D.; Peterson, G.; Takahashi, N. The value of exchange. Soc. Forces 2001, 80, 159–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P. An empirical study of the relationship between individual-based performance appraisal and team performance. Nankai Bus. Rev. 2009, 12, 51–56. [Google Scholar]

- Cravens, K.S.; Oliver, E.G.; Oishi, S.; Stewart, J.S. Workplace culture mediates performance appraisal effectiveness and employee outcomes: A study in a retail setting. J. Manag. Account. Res. 2015, 27, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Hu, B.; Qiu, M. Job satisfaction as a mediator in the relationship between performance appraisal and voice behavior. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 2014, 42, 1315–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, M.; Hu, B.; Xu, Z.; Li, Y. Employees’ psychological ownership and self-efficacy as mediators between performance appraisal purpose and proactive behavior. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 2015, 43, 1101–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Wu, P.; Leung, K. Individual performance appraisal and appraisee reactions to workgroups: The mediating role of goal interdependence and the moderating role of procedural justice. Pers. Rev. 2011, 40, 87–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kampkötter, P. Performance appraisals and job satisfaction. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2017, 28, 750–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.; Holzer, M. Public employees and performance appraisal: A study of antecedents to employees’ perception of the process. Rev. Public Pers. Adm. 2016, 36, 31–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.S.; Park, T.Y.; Koo, B. Identifying organizational identification as a basis for attitudes and behaviors: A meta-analytic review. Psychol. Bull. 2015, 141, 1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngo, H.Y.; Loi, R.; Foley, S.; Zheng, X.; Zhang, L. Perceptions of organizational context and job attitudes: The mediating effect of organizational identification. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2013, 30, 149–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Üngüren, E.; Arslan, S.; KOÇ, T. The Effect of Fatalistic Beliefs Regarding Occupational Accidents on Job Satisfaction and Organizational Trust in Hotel Industry. Adv. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2017, 5, 23–56. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, J.Y.; Lam, S.S.; Chow, C.W. What good soldiers are made of: The role of personality similarity. J. Manag. Psychol. 2015, 30, 1003–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deraman, F.; Ismail, N.; Arifin, A.I.M.; Mostafa, M.I.A. Green practices in hotel industry: Factors influencing the implementation. J. Tour. Hosp. Culin. Arts 2017, 9, 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, D.A. Does serving the community also serve the company? Using organizational identification and social exchange theories to understand employee responses to a volunteerism programme. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2010, 83, 857–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slack, R.E.; Corlett, S.; Morris, R. Exploring employee engagement with (corporate) social responsibility: A social exchange perspective on organizational participation. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 127, 537–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teo, L.; Chan-Serafin, S. Moral foundations in organizations: Exploring the role of moral concerns and organizational identification on unethical pro-organizational behaviors. In Proceedings of the meeting of the Australia and New Zealand Academy of Management, Hobart, Australia, 4–6 December 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd, N.M.; Nowell, B. Testing a theory of sense of community and community responsibility in organizations: An empirical assessment of predictive capacity on employee well-being and organizational citizenship. J. Community Psychol. 2017, 45, 210–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farmer, S.M.; Van Dyne, L.; Kamdar, D. The contextualized self: How team–member exchange leads to coworker identification and helping OCB. J. Appl. Psychol. 2015, 100, 583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Dick, R.; van Knippenberg, D.; Kerschreiter, R.; Hertel, G.; Wieseke, J. Interactive effects of work group and organizational identification on job satisfaction and extra-role behavior. J. Vocat. Behav. 2008, 72, 388–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mael, F.; Ashforth, B.E. Alumni and their alma mater: A partial test of the reformulated model of organizational identification. J. Organ. Behav. 1992, 13, 103–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, D.T.; Sendjaya, S.; Hirst, G.; Cooper, B. Does servant leadership foster creativity and innovation? A multi-level mediation study of identification and prototypicality. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 1395–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loi, R.; Chan, K.W.; Lam, L.W. Leader–member exchange, organizational identification, and job satisfaction: A social identity perspective. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2014, 87, 42–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKinnon, D.P.; Lockwood, C.M.; Hoffman, J.M.; West, S.G.; Sheets, V. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychol. Methods 2002, 7, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhee, J.; Zhao, X.; Jun, I.; Kim, C. Effects of collectivism on Chinese organizational citizenship behavior: Guanxi as moderator. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 2017, 45, 1127–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Chen, H.; Long, R.; Qi, H.; Cui, X. Evaluation of the derivative environment in coal mine safety production systems: Case study in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 143, 377–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belle, N.; Cantarelli, P.; Belardinelli, P. Cognitive Biases in Performance Appraisal: Experimental Evidence on Anchoring and Halo Effects with Public Sector Managers and Employees. Rev. Public Pers. Adm. 2017, 37, 275–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Methot, J.R.; Lepak, D.; Shipp, A.J.; Boswell, W.R. Good citizen interrupted: Calibrating a temporal theory of citizenship behavior. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2017, 42, 10–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozionelos, N.; Singh, S.K. The relationship of emotional intelligence with task and contextual performance: More than it meets the linear eye. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2017, 116, 206–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolino, M.C.; Klotz, A.C.; Turnley, W.H.; Harvey, J. Exploring the dark side of organizational citizenship behavior. J. Organ. Behav. 2013, 34, 542–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deepa, E.; Palaniswamy, R.; Kuppusamy, S. Effect of performance appraisal system in organizational commitment, job satisfaction and productivity. J. Contemp. Manag. Res. 2014, 8, 72. [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter, N.C.; Berry, C.M.; Houston, L. A meta-analytic comparison of self-reported and other-reported organizational citizenship behavior. J. Organ. Behav. 2014, 35, 547–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, J.D. Organizations in Action; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | ū | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. DPA | 3.45 | 0.89 | 1 | |||||||

| 2. EPA | 2.91 | 1.20 | 0.21 ** | 1 | ||||||

| 3. OCB | 3.90 | 0.76 | 0.46 ** | 0.18 ** | 1 | |||||

| 4. OCB-I | 3.63 | 0.89 | 0.43 ** | 0.21 ** | 0.83 ** | 1 | ||||

| 5. OCB-G | 4.02 | 0.80 | 0.42 ** | 0.15 ** | 0.93 ** | 0.67 ** | 1 | |||

| 6. OCB-O | 3.98 | 0.85 | 0.42 ** | 0.13 ** | 0.92 ** | 0.65 ** | 0.84 ** | 1 | ||

| 7. OCB-S | 3.99 | 0.92 | 0.38 ** | 0.14 ** | 0.86 ** | 0.59 ** | 0.76 ** | 0.81 ** | 1 | |

| 8. OID | 3.74 | 0.86 | 0.53 ** | 0.18 ** | 0.60 ** | 0.53 ** | 0.55 ** | 0.53 ** | 0.50 ** | 1 |

| OID | OCB | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | M2 | M3 | M4 | M5 | M6 | M7 | |

| Health | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.08 * | 0.04 |

| Marriage | −0.00 | −0.02 | −0.03 | −0.03 | −0.03 | −0.04 | −0.03 |

| Age | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.03 |

| Education | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.02 |

| Tenure | −0.02 | −0.04 | −0.03 | −0.03 | −0.02 | −0.05 | −0.03 |

| Income | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.10 ** | 0.11 ** | 0.10 ** | 0.14 ** | 0.10 ** |

| DPA | 0.53 ** | 0.45 ** | 0.20 ** | ||||

| EPA | 0.18 ** | 0.17 ** | 0.07 ** | ||||

| OID | 0.58 ** | 0.48 ** | 0.57 ** | ||||

| R2 | 0.24 | 0.40 | 0.07 | 0.38 | |||

| ΔR2 | 0.16 | 0.31 | |||||

| F | 30.70 | 57.30 | 6.836 | 51.69 | |||

| OCB-I | OCB-G | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M8 | M9 | M10 | M11 | M12 | M13 | M14 | M15 | M16 | M17 | |

| Health | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.09 * | 0.05 | −0.01 | 0.00 | −0.01 | 0.03 | −0.01 |

| Marriage | −0.04 | −0.04 | −0.04 | −0.05 | −0.04 | −0.02 | −0.02 | −0.02 | −0.03 | −0.02 |

| Age | −0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 |

| Education | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.01 |

| Tenure | −0.06 | −0.06 | −0.05 | −0.08 | −0.06 | −0.03 | −0.04 | −0.03 | −0.06 | −0.03 |

| Income | 0.10 ** | 0.11 ** | 0.09 ** | 0.12 ** | 0.09 ** | 0.10 ** | 0.11 ** | 0.10 ** | 0.13 ** | 0.10 ** |

| DPA | 0.41 ** | 0.20 ** | 0.41 ** | 0.17 * | ||||||

| EPA | 0.21 ** | 0.12 ** | 0.14 ** | 0.05 | ||||||

| OID | 0.51 ** | 0.41 ** | 0.49 ** | 0.54 ** | 0.45 ** | 0.54 ** | ||||

| R2 | 0.21 | 0.33 | 0.08 | 0.31 | 0.19 | 0.34 | 0.05 | 0.32 | ||

| ΔR2 | 0.12 | 0.23 | 0.15 | 0.27 | ||||||

| F | 25.654 | 41.817 | 8.782 | 39.242 | 23.151 | 43.806 | 4.692 | 40.249 | ||

| OCB-O | OCB-S | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M18 | M19 | M20 | M21 | M22 | M23 | M24 | M25 | M26 | M27 | |

| Health | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.09* | 0.06 |

| Marriage | −0.03 | −0.03 | −0.03 | −0.04 | −0.03 | −0.02 | −0.02 | −0.02 | −0.03 | −0.02 |

| Age | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.05 * | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.05 |

| Education | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.03 | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.02 | 0.00 |

| Tenure | −0.01 | −0.01 | 0.00 | −0.03 | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.01 |

| Income | 0.08 * | 0.09 * | 0.08 * | 0.11 ** | 0.08 * | 0.08 * | 0.09 * | 0.07 * | 0.10 ** | 0.08 * |

| DPA | 0.41 ** | 0.20 ** | 0.37 ** | 0.15 ** | ||||||

| EPA | 0.12 ** | 0.03 | 0.14 ** | 0.05 | ||||||

| OID | 0.52 ** | 0.41 ** | 0.51 ** | 0.49 ** | 0.41 ** | 0.48 ** | ||||

| R2 | 0.20 | 0.32 | 0.04 | 0.29 | 0.16 | 0.28 | 0.05 | 0.27 | ||

| ΔR2 | 0.12 | 0.25 | 0.12 | 0.22 | ||||||

| F | 24.152 | 39.936 | 4.405 | 35.112 | 18.791 | 33.704 | 4.609 | 31.402 | ||

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lu, H.; Yue, A.; Han, Y.; Chen, H. Exploring the Effect of Different Performance Appraisal Purposes on Miners’ Organizational Citizenship Behavior: The Mediating Role of Organization Identification. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4254. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10114254

Lu H, Yue A, Han Y, Chen H. Exploring the Effect of Different Performance Appraisal Purposes on Miners’ Organizational Citizenship Behavior: The Mediating Role of Organization Identification. Sustainability. 2018; 10(11):4254. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10114254

Chicago/Turabian StyleLu, Hui, Ailing Yue, Yu Han, and Hong Chen. 2018. "Exploring the Effect of Different Performance Appraisal Purposes on Miners’ Organizational Citizenship Behavior: The Mediating Role of Organization Identification" Sustainability 10, no. 11: 4254. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10114254

APA StyleLu, H., Yue, A., Han, Y., & Chen, H. (2018). Exploring the Effect of Different Performance Appraisal Purposes on Miners’ Organizational Citizenship Behavior: The Mediating Role of Organization Identification. Sustainability, 10(11), 4254. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10114254