The Chinese Socio-Cultural Sustainability Approach: The Impact of Conservation Planning on Local Population and Residential Mobility

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Material and Methods

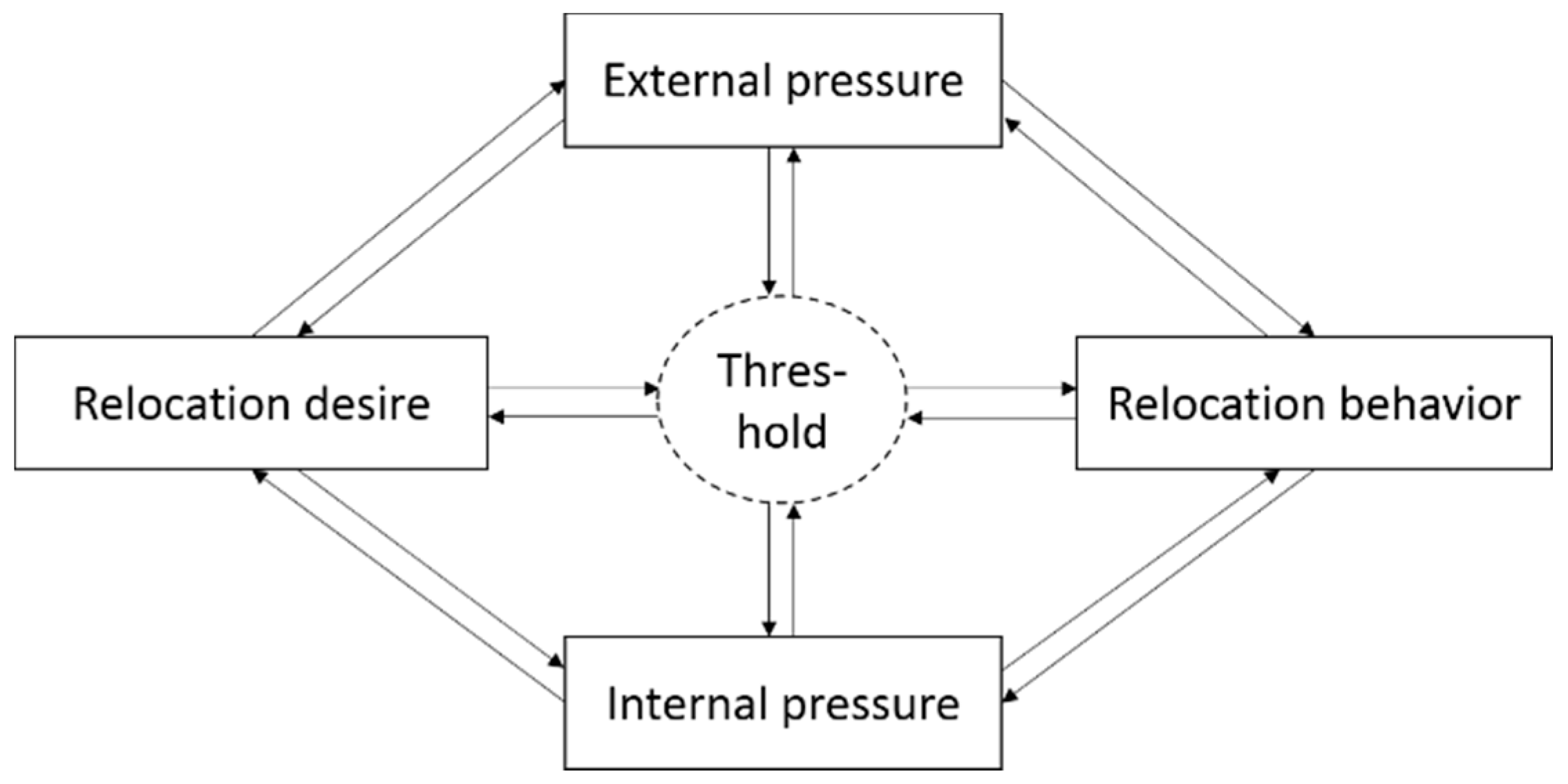

3.1. Research Framework

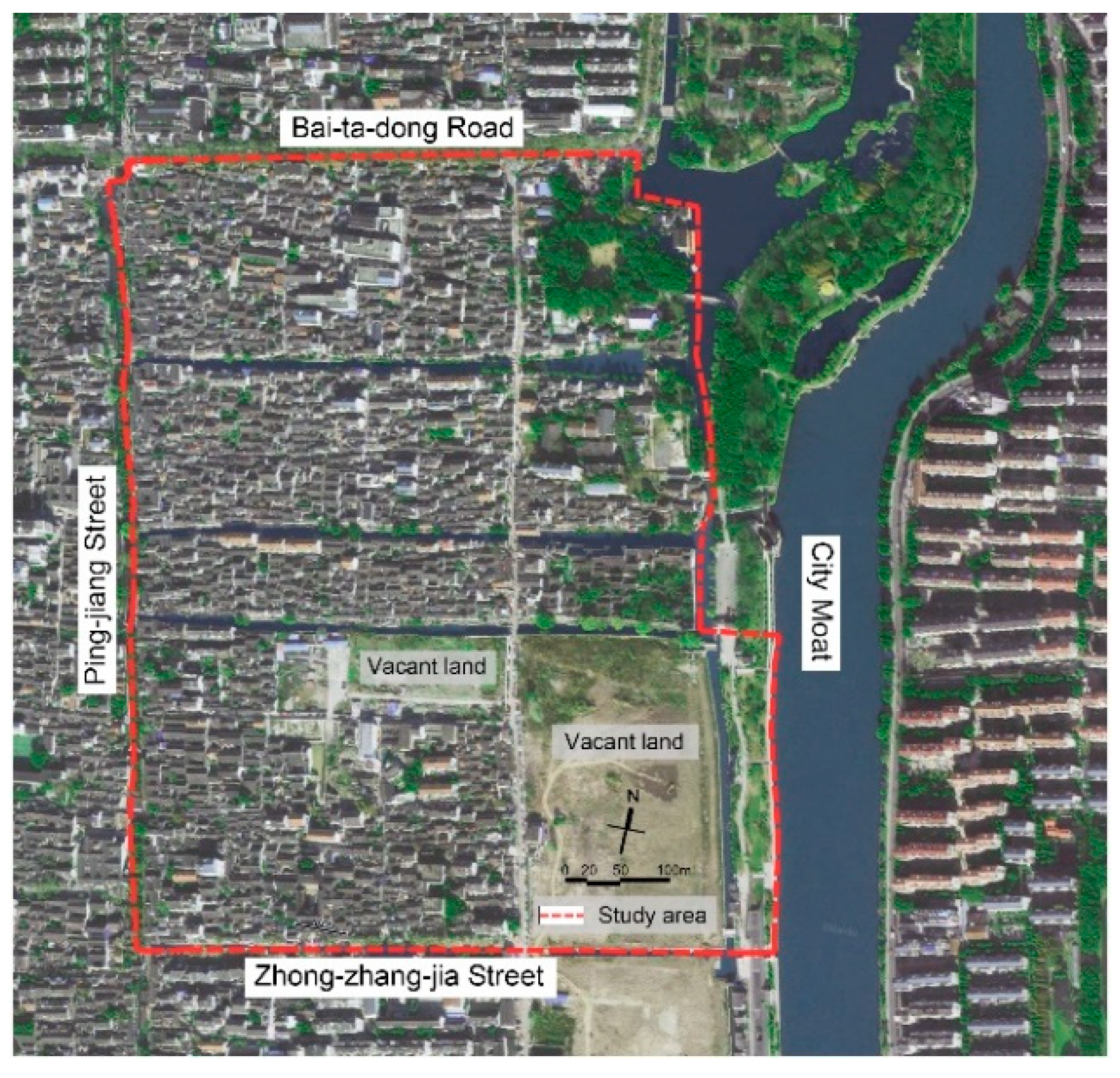

3.2. Data and Methods

3.2.1. In-Situ Analysis

3.2.2. Social survey

3.2.3. Regression Analysis

4. Results

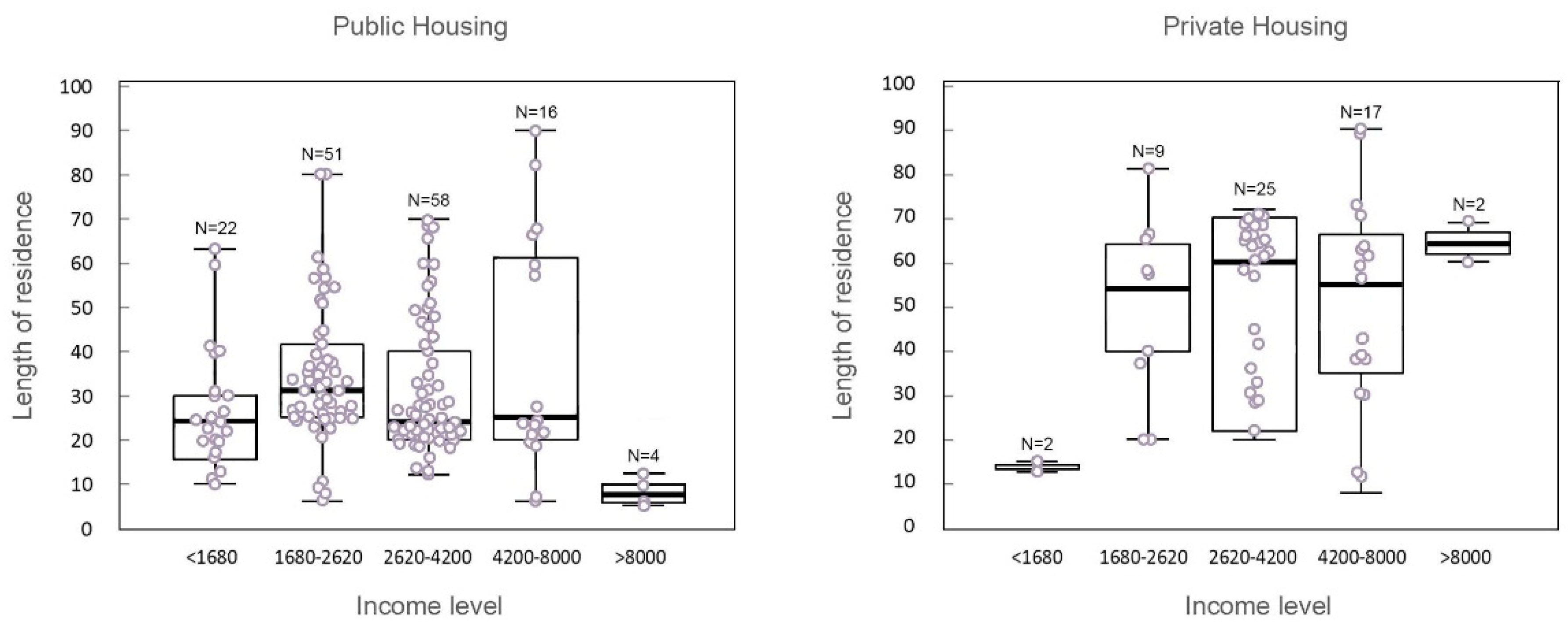

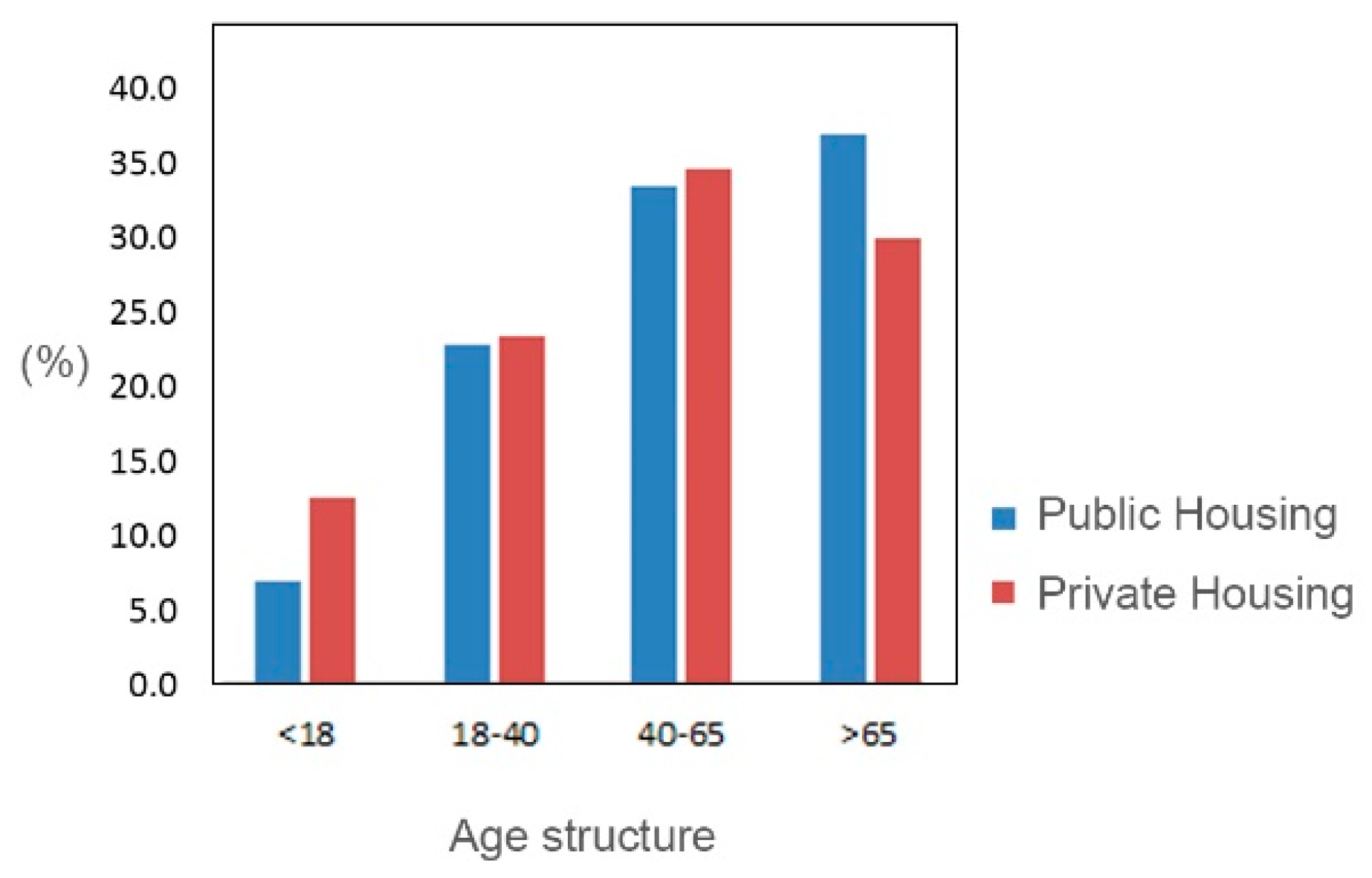

4.1. Stable Population and Housing Policy

4.2. Differentiated Relocation Desire and Population Displacement

4.2.1. Determinants of Relocation Desire

4.2.2. Emerging Population Displacement

5. Conclusions and Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UNESCO. Recommendation on the Historic Urban Landscape; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, C.; Kong, L. Cultural Economy: A Critical Review. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2005, 29, 541–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, S. Bilbao and Barcelona ‘in Motion’. How Urban Regeneration ‘Models’ Travel and Mutate in the Global Flows of Policy Tourism. Urban Stud. 2011, 48, 1397–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, N. New Globalism, New Urbanism: Gentrification as Global Urban Strategy. Antipode 2002, 34, 427–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchini, F.; Parkinson, M. Cultural Policy and Urban Regeneration: The West European Experience; Manchester University Press: Manchester, UK, 1993; pp. 285–286. [Google Scholar]

- ICOMOS. The Valletta Principles for the Safeguarding and Management of Historic Cities. Towns and Urban Areas; CIVVIH: Athen, Greece, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- WHITRAP. City and Society: Community, Space, and Governance. In Proceedings of the Annual Conference of World Heritage Institute of Training and Research for the Asia and the Pacific Regional under the Eauspices of UNESCO, Shanghai, China, 10–11 April 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.H. Between Cultural Value and Economic Value: The Conservation and Reuse of Architectural Heritages in Shanghai City; China Electric Power Press: Beijing, China, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.Q.; Wu, M.W. Modern Urban Renewal; Southeast University Press: Nanjing, China, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Ruan, Y.S.; Zhang, Y.H. The development of Shanghai’s urban conservation and consideration of the conservation of China’s historic cities. Urban Plan. Forum (China) 2005, 1, 68–71. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.P. A study on the commercialization of historic districts. Urban Plan. Forum (China) 2012, 4, 105–112. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.B. Exploring the happiness and dignity in historic areas: The event of social discussion on protecting Nanjing Lao-cheng-nan historic area. Jiangsu Urban Plan. (China) 2010, 11, 13–18. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, B.; Kang, X.Y. Review on the conservation plan of China’s Historic and Famous City. China Ancient City 2011, 1, 27–33. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, W.; Chen, Q.H. Comparative study on tourism development mode in historic towns: Venice and Lijiang. City Plan. Rev. (China) 2006, 30, 76–82. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.P.; Xie, X.; Xiao, H.W. From instruction to inclusion: Remolding governmental value option in historical block preservation. Planners (China) 2016, 32, 109–115. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, K.P. Promoting State Governance System and Governance Capacity Modernization; The Central Party School Pressing House: Beijing, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Yung, E.L.K.; Zhang, Q.; Chan, E.H.W. Underlying social factors for evaluating heritage conservation in urban renewal districts. Habitat Int. 2017, 66, 135–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, G. Comparison of critical success paths for historic district renovation and redevelopment projects in China. Habitat Int. 2017, 67, 54–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X. The Systemic Strategies Research on the Protecting and Organic Renewal of Historic Residential Area in Old Beijing; Tsing University: Beijing, China, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.Y. A Study on Implementation Approach of Historic District Protection. Master’s Thesis, China Academy of Urban Planning and Design, Beijing, China, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison, N.; Xian, S. High mountains and the faraway emperor: Overcoming barriers to citizen participation in China’s urban planning practices. Habitat Int. 2016, 57, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdini, G. Is the incipient Chinese civil society playing a role in regenerating historic urban areas? Evidence from Nanjing, Suzhou and Shanghai. Habitat Int. 2015, 50, 366–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhao, M. Gentrification phenomena and planning countermove in historic conservation. China Ancient City 2010, 9, 4–10. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.C.; He, X.J. Protection and development of Suzhou ancient city from gentrification view point. Planners (China) 2017, 6, 106–111. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, S.D.; Yu, Y.; Li, K.C. Historic conservation in rapid urbanization: A case study of the Hankow historic concession area. J. Urban Des. 2017, 22, 433–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.B. Residential redevelopment and the entrepreneurial local state: The implications of Beijing’s shifting emphasis on urban redevelopment policies. Urban Stud. 2009, 46, 2815–2839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.L. State dominance in urban redevelopment: Beyond gentrification in urban China. Urban Aff. Rev. 2016, 52, 631–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, B.X. Thoughts on the regulations on historic city, town and villages. China Ancient City 2010, 1, 4–9. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, A.J. Study on the implementation of the Regulations on Historic City, Town and Villages. China Ancient City 2010, 5, 4–7. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, Q.F.; Cai, T.S. Improving the system of historic and cultural heritage promotion through social participation: Based on the practice of Guangdong. City Plan. Rev. (China) 2018, 42, 92–100. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, Y.Y.; Huang, H.Y. A study on the community participation model of tourism development of the historical and cultural preservation zones. Hum. Geogr. (China) 2008, 23, 94–98. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Z.X. Dynamic conservation and cultural inheritance. Beijing Plan. Rev. (China) 2015, 6, 180–182. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S. Retrospection on China’s legislation for historic and cultural city conservation. City Plan. Rev. (China) 2011, 20, 56–64. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Y.L.; Huang, Y. A study on the relevance between physical form and social network of historical district. Planners (China) 2018, 8, 101–105. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.G.; Wu, F.L. Residential Satisfaction in China’s Informal Settlements: A case study of Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou. Urban Geogr. 2013, 34, 923–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.H.; Du, X.J. Assessment and determinants of residential satisfaction with public housing in Hangzhou, China. Habitat Int. 2015, 47, 218–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Feng, T.; Timmermans, H.; Li, H.P. A gap-theoretical path model of residential satisfaction and intention to move house applied to renovated historical blocks in two Chinese cities. Cities 2017, 71, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.H.; Xie, M.; Kwan, M.P. Ageing in place and ageing with migration in the transitional context of urban China: A case study of ageing communities in Guangzhou. Habitat Int. 2015, 49, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.H.; Deng, L.F.; Kwan, M.P.; Yan, R.G. Social and spatial differentiation of high and low income groups’ out-of-home activities in Guangzhou, China. Cities 2015, 45, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.J.; Qi, X.L. Determinants of relocation satisfaction and relocation intention in Chinese cities: An empirical investigation on three types of residential neighborhood in Guangzhou. Sci. Geogr. Sin. (China) 2014, 34, 1327–1336. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, J.; Heath, T. Conservation and revitalization of historic streets in China: Pingjiang Street, Suzhou. J. Urban Des. 2017, 22, 455–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICOMOS. The Quebec Charter for the Interpretation and Preservation of Cultural Heritage sites. In Proceedings of the 16th General Assembly of ICOMOS, Québec, QC, Canada, 30 September–4 October 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kan, K. Residential mobility and social capital. J. Urban Econ. 2007, 61, 436–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, Y.; Li, P.; Qiu, L.J. Housing search and housing choice in urban China. Urban Stud. 2017, 54, 1851–1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.H.; Chen, N. A geographically weighted regression approach to investigating the spatially varied built-environment effects on community opportunity. J. Transp. Geogr. 2017, 62, 136–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, D.S.; Kwan, M.P.; Zhang, W.Z.; Fan, J.; Yu, J.H.; Dang, Y.X. Assessment and determinants of satisfaction with urban livability in China. Cities 2018, 79, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowok, B.; Findlay, A.; Mccollum, D. Linking residential relocation desires and behaviour with life domain satisfaction. Urban Stud. 2018, 55, 870–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.M.; Mao, S.Q. Exploring residential mobility in Chinese cities: An empirical analysis of Guangzhou. Urban Stud. 2017, 54, 3718–3737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdin, A. La Question Locale; Presses Universitaires de France: Paris, France, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Tiesdell, S.; Oc, T.; Heath, T. Revitalizing Historic Urban Quarters; Architectural Press: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Ryberg-Webster, S. Heritage amid an urban crisis: Historic preservation in Cleveland, Ohio’s Slavic Village neighborhood. Cities 2016, 58, 10–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, S.; Paddison, R. Introduction: The rise and rise of culture-led urban regeneration. Urban Stud. 2005, 42, 833–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van De Kaa, D.J. Demographic challenges for the twenty-first century. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2010, 610, 107–113. [Google Scholar]

- Zukin, S. Naked City: The Death and Life of Authentic Urban Places; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Franco, S.F.; Macdonald, J.L. The effects of cultural heritage on residential property values: Evidence from Lisbon, Portugal. Reg. Sci. Urban Econ. 2018, 70, 35–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Y. Features and effects of housing policies in French urban revitalization. City Plan. Rev. (China) 2011, 35, 86–92. [Google Scholar]

- Pipa, H.; de Brito, J.; Cruz, C.O. Sustainable rehabilitation of historical urban areas: Portuguese case of the urban rehabilitation societies. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2016, 143, 05016011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrosius, J.D.; Gilderbloom, J.I.; Hanka, M.J. Back to Black … and Green? Location and policy interventions in contemporary neighborhood housing markets. Hous. Policy Debate 2010, 20, 457–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landorf, C. Evaluating social sustainability in historic urban environments. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2011, 17, 463–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, I. Community participation as a tool for conservation planning and historic preservation: The case of “Community as A Campus” (CAAC). J. Hous. Built Environ. 2018, 33, 519–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.H.; Jiao, Z. A comparative study of the renewal of historic conservation areas in historic urban areas of China and UK industrial cities: Pinzijie in Foshan & Colmore Row and Environs in Birmingham. Mod. Urban Res. (China) 2018, 1, 35–43. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, W.L.; Li, W.M. Literature review on the assessment of historic city conservation planning implementation. Huazhong Archit. (China) 2018, 1, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, B.X. The situation, problem and strategy for Chinese Conservation of Historic Cities. China Ancient City 2012, 4–9. Available online: http://www.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx?QueryID=13&CurRec=1&filename=ZGMI201212003&dbname=CJFD2012&dbcode=CJFQ&pr=&urlid=&yx=&v=MTc0ODBlWDFMdXhZUzdEaDFUM3FUcldNMUZyQ1VSTEtlWnVkdEZ5N2tVTHZMUHlyR1o3RzRIOVBOclk5Rlo0Ujg= (accessed on 12 November 2018). (In Chinese).

- Li, H. “Liang-Chen Project” and “Luoyang Mode”: Comparison and inspiration on the planning pattern of constructing a new town near the old city. Urban Plan. Int. 2018, 30, 106–116. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Conservation Plan Making Requirements of Historic and Cultural Cities, Towns and Villages; NCHA, Ed.; MOHURD: Beijing, China, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.T. The Study of Conservation and Control Guidelines of Dujunfu-Zhonggulou Historic Area in Taiyuan; Tsinghua University: Beijing, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, M.; Zheng, W.L.; Wang, J.; Xu, L.; Tao, S.Q. Significance and priorities of establishing China’s historic district conservation system. City Plan. Rev. (China) 2016, 40, 30–38. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.S. The complexity of property ownership in historic area conservation. Urban Plan. Forum (China) 2018, 1, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, Y.; Wang, L.L. Strategies for heritage conservation and living condition improvement from the Perspective of property right system: A case study of public residential heritage in shanghai. City Plan. Rev. (China) 2016, 40, 73–80. [Google Scholar]

- Musterd, S.; Van Gent, W.P.C.; Das, M.; Latten, J. Adaptive behaviour in urban space: Residential mobility in response to social distance. Urban Stud. 2014, 53, 227–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davison, J. Housing Policy and Residential Mobility. In Proceedings of the National Housing Conference, Perth, Australia, 26–28 October 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Stone, J.; Berrington, A.; Falkingham, J. Gender, Turning Points, and Boomerangs: Returning Home in Young Adulthood in Great Britain. Demography 2014, 51, 257–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailey, A.J. Population geography: Lifecourse matters. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2009, 33, 407–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, W.A.V. Life course events and residential change: Unpacking age effects on the probability of moving. J. Popul. Res. (Canberra) 2013, 30, 319–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourne, L.S. The Geography of Housing; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Coulter, R.; Scott, J. What motivates residential mobility? Re-examining self-reported reasons for desiring and making residential moves. Popul. Space Place 2015, 21, 354–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Serrano, L.; Stoyanova, A.P. Mobility and housing satisfaction: An empirical analysis for 12 EU countries. J. Econ. Geogr. 2010, 10, 661–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibem, E.O.; Aduwo, E.B. Assessment of residential satisfaction in public housing in Ogun State, Nigeria. Habitat Int. 2013, 40, 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woosnam, K.M.; Norman, W.C.; Ying, T.Y. Exploring the theoretical framework of emotional solidarity between residents and tourists. J. Travel Res. 2009, 48, 245–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrill, R. Residents’ attitudes toward tourism development: A literature review with implications for tourism planning. J. Plan. Lit. 2016, 18, 251–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rioux, L.; Werner, C. Residential satisfaction among aging people living in place. J. Environ. Psychol. 2011, 31, 158–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Du, X.; Yu, X. Home ownership and residential satisfaction: Evidence from Hangzhou, China. Habitat Int. 2015, 49, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, H.; Folmer, H.; Vlist, A.J.V.D. The impact of home ownership on life satisfaction in urban China: A propensity score matching analysis. J. Happiness Stud. 2016, 19, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arthurson, K. From stigma to demolition: Australian debates about housing and social exclusion. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2004, 19, 255–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razzu, G. Urban redevelopment, cultural heritage, poverty and redistribution: The case of Old Accra and Adawso House. Habitat Int. 2005, 29, 399–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, D.J.; Xu, G.H.; He, L.; Zhang, M.; Lin, D. What determines the preference for future living arrangements of middle-aged and older people in urban China? PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0180764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Basic Information | |||||

| Gender | male | female | |||

| Hukou | local | non-local | |||

| Age | <18 | 18–25 | 25–40 | 40–65 | >65 |

| Employment | Retired | Employed | Unemployed | other | |

| Income level * (RMB/month) | <1680 | 1680–2620 | 2620~4200 | 4200–8000 | >8000 |

| Family size (person) | 1\2\3\4\5\6\7 … other numbers: ____; | ||||

| Family structure | Live alone or with partner | Core family | Stem family | Joint family and other | |

| Property ownership | Public housing | Private housing | Danwei housing | Rented and others | |

| Housing area | _____m2 | ||||

| Length of residence (year) | <1 | 1–3 | 3–10 | 10–18 | >18 |

| Sense of community | 1\2\3\4\5 (1 = weak, 5 = strong) | ||||

| Neighborhood communication | 1\2\3\4\5, (1 = none, high frequency) | ||||

| Subjective Evaluation | |||||

| Housing condition | 1\2\3\4\5\6\7 (1 = very bad, 7 = very good) | ||||

| Infrastructure | 1\2\3\4\5\6\7 (1 = very bad, 7 = very good) | ||||

| Road and traffic | 1\2\3\4\5\6\7 (1 = very bad, 7 = very good) | ||||

| Public facility | 1\2\3\4\5\6\7 (1 = very bad, 7 = very good) | ||||

| Tourism disturbance | 1\2\3\4\5 (1 = high disturbance, 5 = none disturbance) | ||||

| Expected rent | 1\2\3\4\5 (1 = very high; 5 = very low) | ||||

| Have tourism income? | yes | no | |||

| Relocation Desire | |||||

| Do you want to move? | yes | no | |||

| How much do you want to move? | 1\2\3\4\5 (1 = strong intention to move, 5 = not at all) | ||||

| What matters in relocation decision? | Please list five most import factors1.________; 2. ________; 3. ________; 4. ________; 5. ________; | ||||

| Comments on conservation plan and suggestions for community development? | |||||

| Householder | Family Members | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | Proportion | Number | Proportion | ||

| In total | 272 | 100% | 693 | 100% | |

| Length of residence (year) | <3 * | 28 | 10.3% | -- | -- |

| 3–18 | 39 | 14.3% | -- | -- | |

| >18 | 205 | 75.4% | |||

| Relocation desire (binary) | move | 141 | 51.8% | 487 | 70.3% |

| Not move | 131 | 48.2% | 206 | 29.7% | |

| Variables | Min/Max | Frequency/Coding | Sample (N = 272) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | s.d. | |||

| Relocation desire | 1/5 | 1 = strong, 5 = no desire | 3.02 | 1.61 |

| Living condition factors | ||||

| Housing area (m2) | 7/300 | -- | 56.43 | 47.03 |

| Per capita housing area (m2) | 3.5/60 | -- | 18.54 | 11.52 |

| Housing condition | 1/7 | 1 = very bad, 7 = very good | 3.25 | 1.99 |

| Infrastructure | 1/7 | 1 = very bad, 7 = very good | 3.51 | 1.65 |

| Road and traffic | 1/7 | 1 = very bad, 7 = very good | 3.51 | 1.69 |

| Public facility | 1/7 | 1 = very bad, 7 = very good | 5.65 | 1.24 |

| Tourism development factors | ||||

| Tourism disturbance | 1/5 | 1 = high disturbance, 5 = none | 3.69 | 1.02 |

| Expected rent | 1/5 | 1 = very high, 5 = very low | 2.47 | 1.05 |

| Having tourism income or not | -- | 1 = yes, 0 = no | 0.10 | 0.30 |

| Socio-demographic factors | ||||

| Gender | -- | 1 = male, 0 = female | 0.42 | 0.49 |

| Hukou | -- | 1 = local, 0 = non-local | 0.85 | 0.36 |

| Age | ||||

| <40 | -- | 11.8% | -- | -- |

| 40~65 | -- | 22.8% | -- | -- |

| >65 | -- | 65.4% | -- | -- |

| Employment | ||||

| Retired | -- | 65.4% | -- | -- |

| Employed | -- | 30.1% | -- | -- |

| Unemployed and other | -- | 4.4% | -- | -- |

| Income level (RMB/month) | ||||

| <2620 | -- | 38.2% | -- | -- |

| 2620~4200 | -- | 39.3% | -- | -- |

| >4200 | -- | 22.4% | -- | -- |

| Family size (person) | 1/25 | 3.55 | 2.52 | |

| Family structure | ||||

| Live alone or with partner | -- | 35.3% | -- | -- |

| Core family | -- | 21.3% | -- | -- |

| Stem family | -- | 35.3% | -- | -- |

| Joint family and other | -- | 8.1% | -- | -- |

| Emotional factors | ||||

| Length of residence (year) | ||||

| <3 | -- | 10.3% | -- | -- |

| 3~18 | -- | 14.3% | -- | -- |

| >18 | -- | 75.4% | -- | -- |

| Sense of community | 1/5 | 1 = weak, 5 = strong | 3.46 | 1.30 |

| Neighborhood communication | 1/5 | 1 = none, 5 = high frequency | 3.91 | 1.17 |

| Variables | Model1 Whole Sample | Model2 Public Housing Tenants | Model3 Private Housing Owners | Model4 Migrants and Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relocation desire (1 = strong) | Mean = 3.02 | Mean = 2.75 | Mean = 4.19 | Mean = 2.42 |

| Living condition factors | ||||

| Housing area | 0.004 | 0.010 | −0.001 | 0.000 |

| Per capita living area | 0.001 | −0.004 | 0.020 | −0.029 |

| Housing condition | 0.431 *** | 0.406 *** | 0.300 ** | 0.638 ** |

| Infrastructure | 0.106 * | 0.142 * | −0.036 | 0.033 |

| Road and traffic | 0.031 | −0.006 | 0.058 | 0.013 |

| Public facility | 0.090 | 0.139 | −0.009 | −0.183 |

| Tourism development factors | ||||

| Tourism disturbance | 0.040 | −0.009 | −0.027 | 0.147 |

| Expected rent | 0.168 ** | 0.113 | 0.152 | 0.160 |

| Having tourism income or not | 0.546 * | 0.060 | 0.222 | 1.785 * |

| Socio-demographic factors | ||||

| Gender | 0.135 | 0.120 | 0.106 | 0.442 |

| Hukou | −0.463 | −0.479 | 0.007 | 0.674 |

| Age | 0.003 | 0.335 | −0.644 * | −0.121 |

| Employment | 0.007 | 0.225 | 0.005 | −0.553 |

| Income level (RMB/month) | −0.067 | 0.091 | 0.236 | −0.777 ** |

| Family size (person) | −0.072 | −0.307 * | 0.097 | −0.098 |

| Family structure | −0.090 | 0.044 | −0.013 | 0.188 |

| Emotional factors | ||||

| Length of residence | 0.319 | 0.056 | 1.061 ** | 0.221 |

| Sense of community | 0.114 | 0.082 | 0.612 ** | 0.083 |

| Neighborhood communication | −0.040 | 0.002 | 0.278 | −0.150 |

| Explanatory Variables | N = All | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | B | Exp(B) | |

| Gender | |||

| 0 = female | 58.50% | -- | -- |

| 1 = male | 41.50% | −0.017 | 0.983 |

| Hukou | |||

| 0 = non-local | 14.70% | -- | -- |

| 1 = local | 85.30% | 0.199 | 1.22 |

| Age | |||

| 1 ≤ 40 | 11.80% | 0.253 | 1.288 |

| 2 = 40~65 | 22.80% | 0.758 | 2.134 |

| 3 ≥ 65 (reference) | 65.40% | -- | -- |

| Employment | |||

| 0 = retired | 65.40% | -- | -- |

| 1 = employed | 30.10% | 1.285 | 3.616 |

| 2 = unemployed and other | 4.40% | 0.871 | 2.388 |

| Income level (RMB/month) ** | |||

| 0 ≤ 2620 | 38.20% | -- | -- |

| 1 = 2620~4200 | 39.30% | 1.240 ** | 3.457 |

| 2 ≥ 4200 | 22.40% | 0.474 | 1.606 |

| Family size (person) | -- | 0.102 | 1.107 |

| Family structure *** | |||

| 0 = Live alone or with partner | 35.30% | -- | -- |

| 1 = core family | 21.30% | 0.507 | 1.66 |

| 2 = stem family | 35.30% | 2.003 ** | 7.408 |

| 3 = Joint family and others | 8.10% | 1.390 * | 4.013 |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, Y.; Yang, J. The Chinese Socio-Cultural Sustainability Approach: The Impact of Conservation Planning on Local Population and Residential Mobility. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4195. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10114195

Chen Y, Yang J. The Chinese Socio-Cultural Sustainability Approach: The Impact of Conservation Planning on Local Population and Residential Mobility. Sustainability. 2018; 10(11):4195. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10114195

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Yue, and Jianqiang Yang. 2018. "The Chinese Socio-Cultural Sustainability Approach: The Impact of Conservation Planning on Local Population and Residential Mobility" Sustainability 10, no. 11: 4195. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10114195

APA StyleChen, Y., & Yang, J. (2018). The Chinese Socio-Cultural Sustainability Approach: The Impact of Conservation Planning on Local Population and Residential Mobility. Sustainability, 10(11), 4195. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10114195