1. Introduction

From the 1980s on, Latin American democratic constitutions have established the rights to housing and a healthy environment, and have consolidated the social function of property as a way of limiting the dominance of private property rights [

1]. Although most Latin American countries have adapted their legal interpretations of the social function of property to include ecological functions [

2], the regulation and enforcement of the constitutional rights to housing, private property, and environmental protection can generate land use conflicts, with important repercussions for urban sustainability. This article analyses one concrete conflict between the rights to adequate housing, environmental protection, and private property in Brazil. This land use conflict, which resulted in a court case, represents a common sustainability problem in the Global South: the urbanisation of environmentally protected and private land via the establishment of informal settlements. The goal of this article is to examine the ways in which legal actors and municipal planners enable and/or constrain the fulfilment of the social and ecological functions of private property. Our aim is to identify preventable conflicts between the rights to private property, environmental protection, and housing.

Like other Latin American constitutions, Brazil’s 1988 Constitution established the social function of private property, for both rural and urban land, and recognised housing as a basic right [

3]. The 2001 City Statute (Law 10257) developed these constitutional legal provisions on urban policy (Articles 182 and 183 of the magna letter) to promote community well-being and justice over private property rights, fair distribution of the costs and benefits of urbanisation, and democratic management of the city [

4]. The 1934 Brazilian Constitution first introduced the legal principle of the social function of private property as an external limitation to individual rights, maintaining the principle that the right to property is protected as long as it does not infringe on any social or collective interests [

5].

Regarding the social function of urban property, the Brazilian Supreme Court has interpreted the 1988 Constitution and the 2001 Federal City Statute in ways that limit the profits of real estate developers and landowners. For instance, idle land can be subjected to compulsory parcelling and building, as well as to progressive property and land taxation and expropriation [

5,

6]. Furthermore, the Supreme Court has ruled in favour of guaranteeing the tenure security of informal dwellers via adverse possession of private property and the real right of use concession (concessão de direito real de uso), if the occupied land is public [

5,

7]. Squatters acquire adverse possession claims over private urban land on which they have lived for five consecutive years without landowners’ contestation [

8,

9,

10]. In sum, the social function principle refers to the right to housing and the fair distribution of the profit and costs of urban private property development.

The 1988 Brazilian Constitution established the right to an ecologically balanced environment; nevertheless, this right is not typically addressed in light of the social function of property. By contrast, Colombian and Bolivian constitutional courts have discussed the socioenvironmental or socioecological functions of private property [

3]. In Brazil, it is only with the enactment of the 2002 Civil Code (Law 10406/02, art. 1228 § 1) that socio-economic and environmental limitations on private property rights appear together. Besides establishing the social and economic goals of private property, article 1228 § 1 also required that landowners respect legislation that protects flora, fauna, natural beauty, ecological balance, historical and artistic heritage, and prevents the pollution of air and water. This article also secured landowners’ right to use, enjoy, and dispose of their property, as well as to protect and repossess their property from those who unfairly take possession of it. The fifth subheading of Civil Code’s art. 1228 opened the exception for adverse possession, which takes place when a considerable number of people occupy a large extension of land for five uninterrupted years and, in good faith, improve the area.

Although the Brazilian Constitution explicitly states only that rural property must preserve the environment and its ecological functions, the Superior Tribunal of Justice has maintained that the ecological function of rural land, established in Article 186 of the Constitution, also applies to urban property [

11]. In this study, we address the following questions. Do the social and ecological functions of urban land in the periphery of São Paulo City prevail over private property rights? What happens in the realm of legal and urban governance of land use conflicts when the social and ecological functions of private property collide?

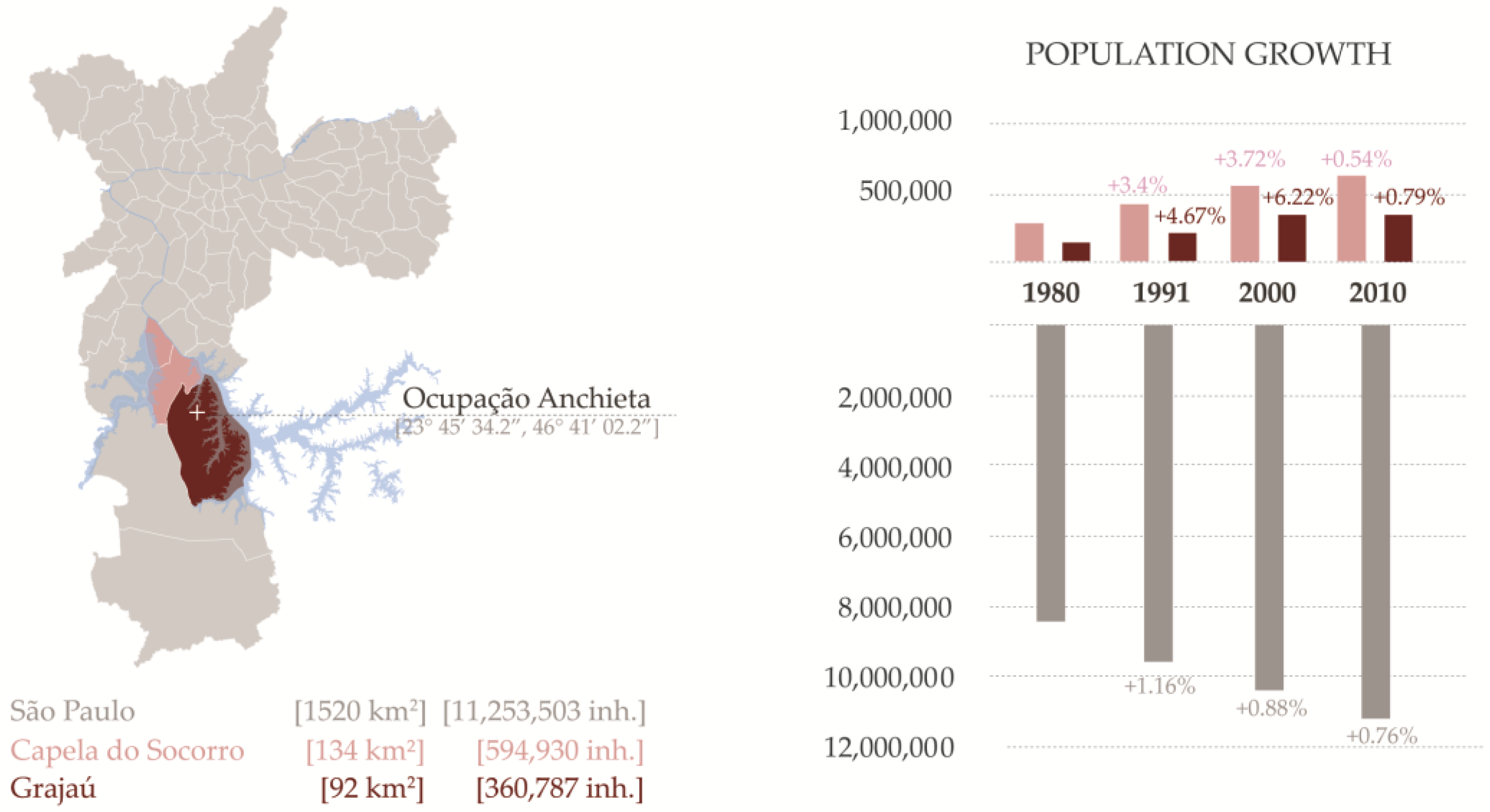

São Paulo, with 11,244,369 people (IGBE, 2010) residing in a concentrated area of 1521.11 km

2, highlights the conflicts emerging from these two fundamental rights. Although the city’s overall population growth rate has decreased in recent years (

Figure 1), the city’s periphery, where most informal settlements are located, continues to experience a burgeoning population growth [

12]. Approximately 900,000 periphery-located homes are threatened by climate change because they are situated on slopes prone to landslides, in floodable areas [

12], or in areas of environmental protection.

Informal housing in São Paulo takes diverse sociospatial forms; a comprehensive taxonomy would include settlement types ranging from cortiços (slum tenements) and illegal land subdivisions to favelas (informal settlements), temporary occupations, and young land occupations. In all cases, the precarious legal nature of such housing underscores the vulnerability of informal inhabitation in terms of the following aspects, tenure insecurity [

13], incomplete infrastructure, unsuitable location, and living in socially vulnerable situations [

14]. Brazil’s urban policy prioritises the upgrading of informal settlements and tenure security over land titling programs [

15,

16]. Municipal governments tend to wait until residents acquire tenure security (not private property rights) before they launch infrastructure upgrading programs. As a result, favelas that are more consolidated receive municipal services, whereas young favelas at the stage of land occupation continue to develop in an unsustainable fashion. During the first five years of a land occupation, either the landowner, if the land is private, or the government, if the land is public, can claim repossession of the property (Brazilian Federal Constitution, art. 183; Civil Procedure Code, art 561).

Thus, younger land occupations in particular lack the assistance and resources required to cope with the incessant threat of displacement. In the early stages of occupation, legal cases often evoke the narrative of environmental degradation and unsustainable practices—because of the impacts of deforestation and the lack of proper infrastructure—to force eviction or deny services. Despite these challenges, young occupations continue to grow rapidly in the periphery of São Paulo, on both public and private property, without consideration of environmental risks and often near environmentally protected areas. By the time municipalities become aware of their existence or determine that it is legally sound to upgrade them, it is often too late to guide their settlement patterns towards healthy and ecologically sensitive development. This planning approach does not include procedures for anticipating and preventing land use conflicts. Unfortunately, lack of consideration of conflict identification and analysis for anticipation, negotiation, and mediation has been the norm among urban planning practitioners and scholars across the globe [

17,

18]. This situation should and could be different. The first years of land occupation remain critical to obtaining legal rights to lands, and land occupiers can become publicly recognised protagonists in creating better, alternative futures for themselves.

2. Materials and Methods

This research comprises the analysis of the legal and policy framework that regulates urban environmental protection, social housing provision, property rights, and land use law in Brazil. We analyse the laws, policies, and court cases that regulate, interpret, and implement the social and ecological functions of private property to a specific land use conflict in the periphery of São Paulo. Understanding law and policy from the point of view of a case study highlights the limitations of the current urban and environmental agenda with respect to issues of informal peripheral urbanisation. Ocupação Anchieta fulfilled our case selection criteria because the lawsuit involves a conflict between private property rights, environmental protection, and the right to housing. Thus, by focusing on this case of a young land occupation in the south of São Paulo, we scrutinize the application of the constitutional principle that establishes the social and ecological functions of property.

We examine the role of legal institutions in mediating urban land conflicts by analysing the arguments in the case proceedings and interviewing those involved with the lawsuit. The case proceedings shed light on the role of legal actors and the uneven access to legal representation of the parties involved. The case includes evidence of the negotiations between the landowner and the occupiers, the roles of the judge, the landowner’s lawyer, the Public Prosecutor’s Office, the Environmental Police, and lastly, the Public Defender’s Office. The interviews with key informants include the four Ocupação Anchieta Association coordinators; representatives of the landowner, Instituto Anchieta Grajaú (IAG) the public defenders and lawyer representing the landowner. We have also interviewed lawyers at the Gaspar Garcia Centre for Human Rights, a nongovernmental organisation (NGO) that provides legal advice and representation in cases involving housing and human rights violations in São Paulo and that has advised, but not legally represented, the Ocupação Anchieta Association.

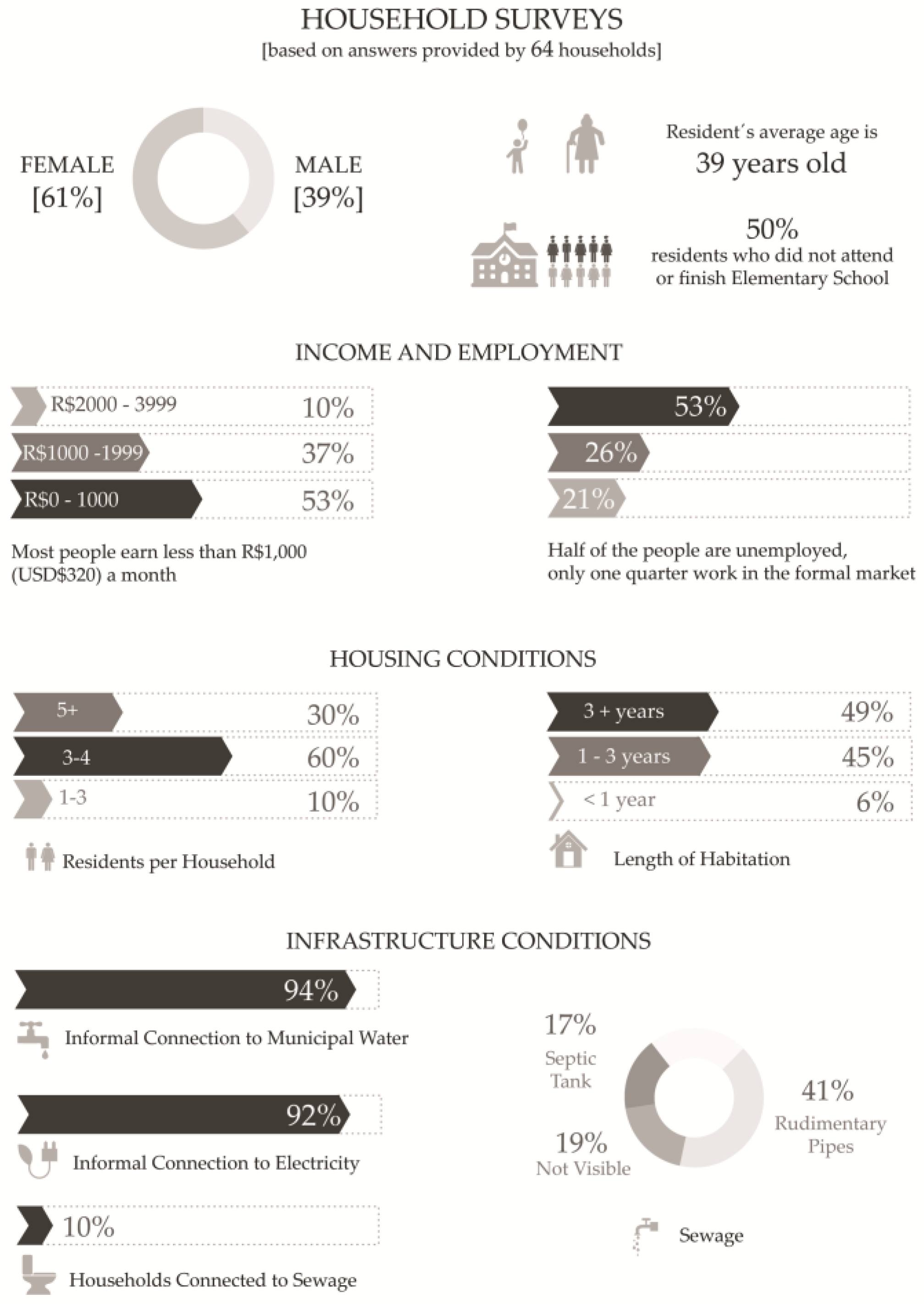

Besides the court case analysis and in-depth interviews with those involved in the lawsuit, the authors conducted fieldwork and engaged with the residents on their land occupation. The fieldwork entailed data collection through teaching and applied research starting with visits in October 2016, followed by in-depth fieldwork in March 2017 and follow-up visits in August 2017 and July–August 2018. The field methods consisted of sociodemographic household surveys, direct observation and mapping of existing housing and infrastructure conditions, and participatory planning meetings to learn from residents’ priorities, all performed in collaboration with the Association and residents. To gain a holistic understanding of the site conditions and the families living there, we conducted a rapid appraisal in collaboration with residents and our planning and architecture students [

19,

20]. This holistic methodology for site-specific fieldwork followed the logic of USAID’s rapid appraisal approach, which maintains that the triangulation of different sources of data collection compensates for the lack of in-depth ethnographic data and of the time and funding required to survey every household.

Informal settlements are not homogeneous spaces, and they vary internally in terms of topography, proximity to natural resources and municipal services (e.g., trash collection), population density, and socioeconomic status [

15,

21]. Thus, the household survey and the direct observation considered the internal geographical diversity of the settlement by dividing the land occupation into sections and streets. We then knocked on every third door on every street in each site section. This sampling logic does not yield a representative sample of the households, so the data are not generalisable. Nonetheless, the data allow us to start gauging the diversity of social and environmental vulnerability challenges in the community. We administered 64 door-to-door household surveys with 22 multiple choice questions and three open-ended questions divided into the following four sections: housing conditions, infrastructure, public and community life, and sociodemographic questions pertaining to the survey respondent and the household. The goal of the survey was to better understand household compositions and capabilities vis-à-vis their housing and infrastructure conditions. By contrast, the direct observation checklist did not require interactions with a household respondent. Checklist items included external housing structure, environmental conditions, and infrastructure indicators from the UN-HABITAT Program, as well as checklist items inspired by the World Health Organization [

22,

23]. We gathered 110 direct observation surveys covering every two housing structures near the creek and every six housing structures in the rest of the occupation. The focus on the natural springs and the creek reflects the concern with environmental protection.

Additionally, the investigation includes a variety of visualisations, ranging from infographics and maps to site images from different stages in the emergence and consolidation of the land occupation. These methods of data visualisation are relevant to understanding the specific nature of young land occupations as an informal typology and its footprint in the context of the city of São Paulo. Whereas the infographics focus on the assemblage of district, submunicipality, and city-level data on population change, the maps and aerial images display overlays of regulatory information regarding land use and zoning types and their changes over time. Last, the site images offer a direct account of the precarious conditions of the homes and the lack of on-site infrastructure provision.

The Ocupação Anchieta case study is a part of a larger research project in which the coauthors are investigating the impact of the courts and the rule of law on informal settlements located in areas of environmental protection or risk. By focusing on young land occupations, the project addresses the urgent need for the various urban actors to reassess their ability to engage with this extremely precarious form of urbanisation.

3. Ocupação Anchieta: History and Actors

Ocupação Anchieta is a five-year-old land occupation in the Vila Nascente neighbourhood of the Grajaú District, 17 miles southwest of downtown São Paulo (

Figure 2). The district belongs to the submunicipality of Capela do Socorro, a water-rich region between the Billings and Guarapiranga Reservoirs. In addition to these critical water supply resources for the metropolitan region of São Paulo, Grajaú District also contains important reserves of the Atlantic Forest, a highly diverse continental biome.

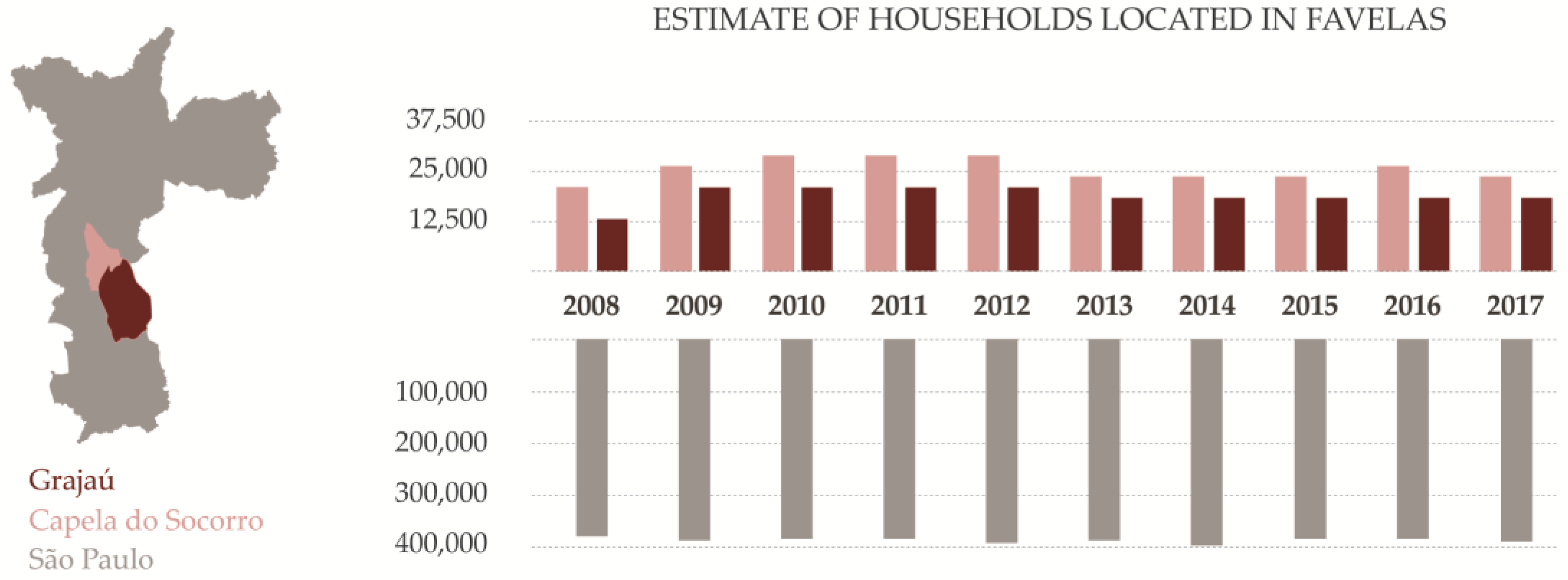

This area, in the south of the city, started to develop in the late 1960s with new industrial zones that lacked the necessary housing provisions for workers. This problem, as well as the unattainable costs of housing in more central locations, led to the urbanisation of the undeveloped land in the region through informal means, such as, in many cases, land occupations and self-built housing that lacked proper infrastructure. In the submunicipality of Capela do Socorro, this process continued from the 1970s to the 1990s despite efforts to contain growth and protect the fragile environment around the reservoirs (Law 878/1975 and Law 1172/1976). As a result, the protected areas around the Guarapiranga and Billings Reservoirs have gradually been occupied, depleting important reserves of the Atlantic Forest and contributing to water pollution. When the municipality initiated a program of land regularisation and upgrading of more consolidated informal areas in the 1990s, the newer occupations adjacent to the Billings Reservoir were left out of the programs of infrastructure provision. The fast pace and intensity of urbanisation in the inter-reservoir region continued [

24], compromising residents’ access to infrastructure and the provision of urban services. Furthermore, this path of informal urbanization has been a challenge for the provisions of the State Laws for Recovery and Protection of Areas in the Guarapiranga and Billings basins, passed in 2006 and 2009, respectively. In recent years, the number of households located in informal settlements in the district and submunicipality of Capela do Socorro has continued to grow (

Figure 3).

Ocupação Anchieta clearly exemplifies these patterns of unsustainable peripheral urbanisation and the challenges faced by residents in gaining the right to the city. Initiated in 2013, the occupation contains natural springs and a creek in an area of permanent preservation (APP) that has been heavily affected over time. The land was severely deforested to make room for the construction of the residents’ homes. These new residents either built a precarious sewage system or linked their shacks to a system that runs throughout portions of the site and informally connects to the municipal network. These circumstances and the lack of sufficient waste management methods have imposed environmental, health, and safety hazards on the residents over time.

Today, the occupation is home to over 800 families living in precarious and unhealthy conditions. Social vulnerability seems to be a widespread problem, because half of our survey respondents, all adult heads of household, did not complete elementary school education. Furthermore, half of the survey respondents are unemployed, and only about one-fourth of them work in the formal economy (see

Figure 4). The landowner, local nonprofit Instituto Anchieta Grajaú (IAG), received the land as a donation from a real estate firm, Cyrela Empreendimentos Imobiliários, for the implementation of a socioeducational project called Projeto Anchieta. The donation had specific instructions regarding the use of the land, and the company remains involved in the decision-making of the nonprofit through participation on its Board of Directors. IAG was established in 1998 through a volunteer effort that aimed to create a pilot project for the social and economic reintegration of families and children vulnerable to social exclusion. The group focuses on educational, health, environmental, and professional capacitation activities. IAG offers after-school education and additional arts, culture, sports, and environmental activities for more than 600 children, teenagers, and youth. They also provide family support through social and job capacitation programs to some 1200 families in the district. Over time, IAG has built a series of modest on-site facilities to operate their educational programs.

The occupation of the land adjacent to IAG’s facilities in July 2013 took the organisation by surprise. In a July 2017 interview, IAG’s president, Roberto Loeb, recalled the tension that the occupation created amongst the nonprofit’s Board of Directors. Besides the provision of educational and social activities, IAG’s mission included environmental stewardship of the on-site land resources. Although the initial occupation threatened to disturb the protected area within the parcel, those occupying the land were the very constituency targeted by IAG’s mission. This conflict remains at the heart of the ongoing legal case initiated in August 2013, as IAG and the Ocupação Anchieta Association continue to negotiate a solution.

The Association has played an important role in community organising, service provision for the residents, and gaining legal representation with the help of an extended network of housing rights groups. The current coordinators did not know one another before the land occupation in 2013 and independently decided to occupy the property to fulfil their families’ need for shelter. Today, the Association is registered, and its members elect their representatives. Although formal associations must pay municipal fees to stay current, the Association does not collect any fees in view of informal dwellers’ financial constraints.

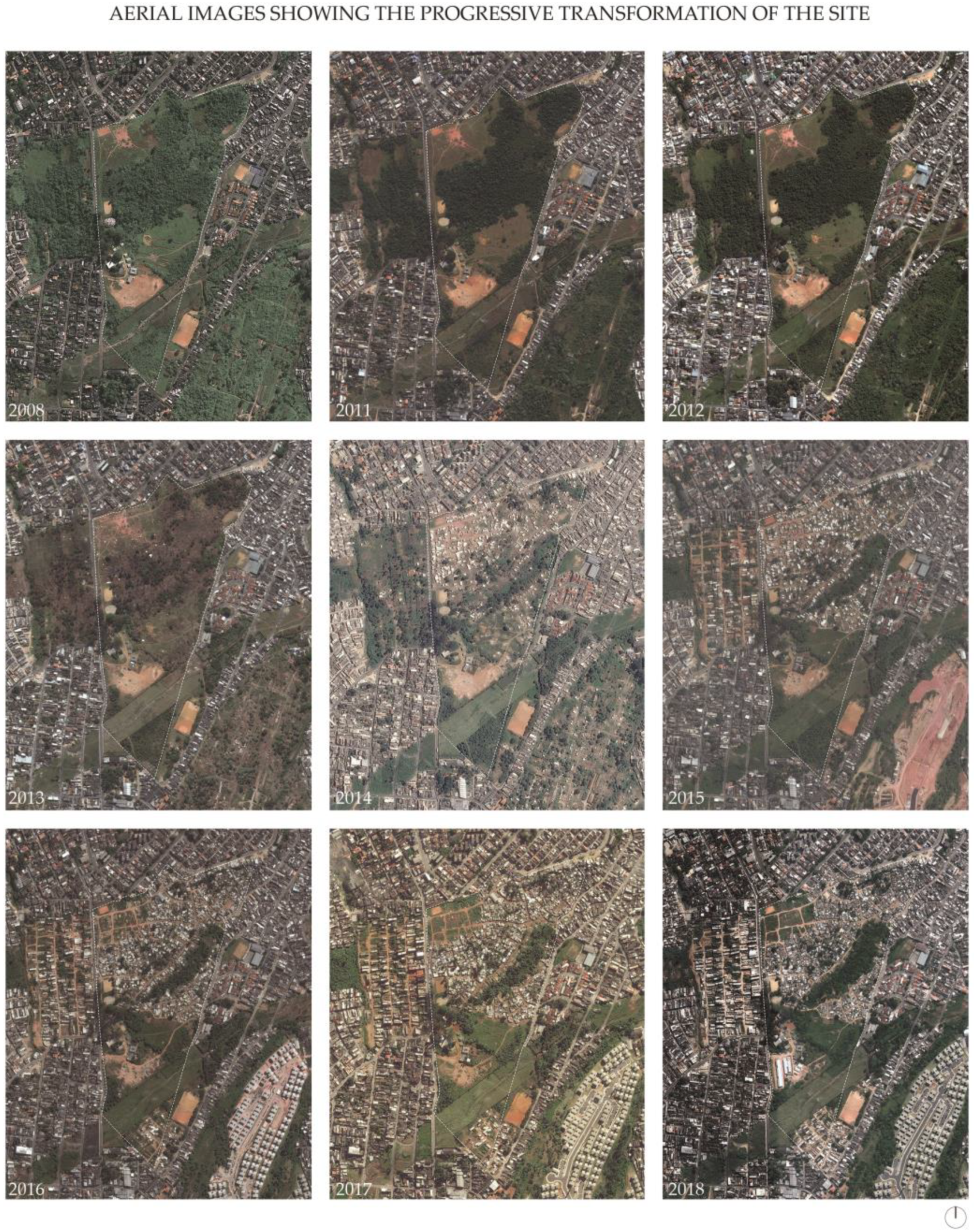

Since the 2013 occupation, the site has undergone several changes in response to the continuous negotiations between the landowner and occupiers. The aerial images in

Figure 5 illustrate the incremental occupation of the site and the effect on forested areas in the first two years. The 2018 image captures the removal of structures in two main areas. The first area was subjected to eminent domain for the development of a project of public interest, the Alziro Pinheiro de Magalhães Municipal Primary School. The second land change was a response to the progressive dismantling of the precarious homes along the site’s bodies of water. Designated as an APP, this portion of the land still contains traces of the Atlantic Forest and is protected by the Federal Forest Code. Responding to the environmental degradation on the site, occupiers initiated the relocation of families living in homes near the bodies of water. Assisted by the nonprofit Teto (Roof), these residents relocated to units situated further from the water.

4. Ocupação Anchieta: The Land’s Environmental Value and Function

According to the description in the legal case, the 220,000 m2 land donation included 136,000 m2 of native Atlantic Forest and an APP. Running north along the centre of the parcel, a seasonal creek and natural springs contribute to the relevant environmental features linked to the Billings Reservoir Watershed. In 1997, State Law 9.866 first established the Watershed Protection and Recovery Areas (Áreas de Proteção e Recuperação dos Mananciais, APRMs) as watersheds of regional interest for public water supply. APRMs would have to establish their intervention areas, jurisdictions, participatory governance, and the respective environmental and urban planning guidelines for site interventions. In 2009, to develop those provisions, State Law 13.579 defined the Area of Protection and Recovery of Springs in the APRM Billings Reservoir Watershed, as regulated by State Decree 55.342/2010. These regulations aimed to intervene in and reorient land occupation processes, guaranteeing priority to the populations residing in the Billings Reservoir Watershed.

Responding to the rapid transformation of the area and recognising the environmental value of the features in the area to the water quality of the Billings Reservoir, Mayor Gilberto Kassab established the provision for the so-called Linear Park Ribeirão Cocaia and designated private property for expropriation. Further regulated under Municipal Decree 52.237/April 12, 2011, the Linear Park included 1,261,516.44 m

2 located along the alluvial plain at Ribeirão Cocaia, in one of the Billings Reservoir subwatersheds (

Figure 6).

Together with its environmental mandate to preserve environmental hydric resources, the park included a wide range of urban conditions and land uses and emphasised the need for land regularisation and urbanisation plans in an area with a large provision of Special Zones of Social Interest (Zona Especial de Interesse Social, ZEIS). Overall, the Cocaia Project would address the lack of proper sanitation facilities and domestic waste management and improve the quality of water draining to the Billings Reservoir.

The plan was never fully implemented, and Mayor Fernando Haddad abandoned the project years later under Decree 56.322/2015. However, the designation of the APP in the site and the required buffer zone without construction on both sides of the bodies of water remain active. The APP is one of the legal resources in the Federal Forest Code (Código Florestal), Law 12.651/2012, designed to promote the protection of the environment in Brazil, addressing both rural and urban lands. APPs play a key environmental role in preserving hydric resources, the landscape, and biodiversity and in ensuring the population’s well-being. In its application in urban areas, the instrument of the APP (first defined in Law 7.803/89 and maintained in the current Forest Code) remains critically important, even though it is contested [

25]. At the centre of the polemics is the lack of a distinction between the scope of regulation of environmentally protected areas in rural and urban lands. Regarding the debate on land regularisation in occupied areas designated as APPs, legal scholars argue that the Forest Code emphasises that technical studies of a particular site play an important role in the evaluation of the remaining ecological function of the specific property and the urban infrastructure available for current low-income residents [

25]. Nonetheless, in analysing about 20 court cases involving informal settlements in APPs situated in São Paulo City, the authors noticed the lack of technical reports substantiating court decisions. This fact is corroborated by interviews conducted on October 2016 with São Paulo state public defenders from the Housing and Urbanism Study Centre, who complained about insufficient funds for hiring geologists, ecologists, and architects who could provide technical support for each pertinent case.

The Forest Code requires land regularisation in ZEISs occupying an APP. The Federal Law of Land Regularization 11.977 of 2017 places further emphasis on municipalities’ responsibility for administering land regularisation. However, the Forest Code remains ambiguous regarding the urban activities permitted in areas defined as APPs: once consolidated, the ecological function of the land and its recovery capacity are diminished. Current legal debates [

26] have called for a more precise articulation of the application of APPs in urban land to avoid additional overlaps with other legal provisions that observe fewer restrictions to their occupation. This remains at the centre of the conflict between the flexibility applied in the land regularisation of zones of social interest housing in urban areas and the implementation and enforcement of existing environmental legislation [

27].

Brazil has made a notable investment in developing the capacity for environmental enforcement [

28]. Concretely, the Public Prosecutor’s Office (Ministério Público) has the power to file civil and criminal lawsuits to protect the environment [

28,

29]. Prosecutors may file some of these lawsuits against both municipalities and land occupiers when the occupied land belongs to the municipal government and destroys the environment [

30]. Even when the occupied land is private, the municipal government may become a defendant for failing to fulfil its city planning function, including, but not limited to, the provision of infrastructure for informal settlements. In fact, during in-depth interviews on October 2016, public prosecutors from the Centre for Technical Support on the Environment, Housing, and Urbanism, at the São Paulo State Public Prosecutors’ Office, reported to us that failures in urban governance and the lack of municipal capacity to implement master plans and enforce zoning ordinances are the root causes of most lawsuits in areas of environmental risk.

5. The São Paulo Master Plan and the Site as a ZEIS 4: Valuing the Social Function of Urban Property

Article 182 of the 1988 Federal Constitution attributes to municipal master plans the power to define the social function of urban property [

31] according to general principles, which were later regulated by the Federal City Statute of 2001. For some scholars, the master plan, which is mandatory for all Brazilian cities with over 20,000 inhabitants, plays the most important role in establishing and guaranteeing the social functions of the city. Regarding the social function of urban property specifically, Article 39 of the Federal City Statute establishes this obligation for all master plans [

32]. São Paulo’s most recent master plan, Law 16.050/2014, defines a set of goals—‘to humanize and rebalance the city of São Paulo, bringing housing and jobs closer together and facing socio-territorial inequalities’—and describes a series of strategies for their realization [

33]. The 2014 Strategic Master Plan (Plano Diretor Estratégico, PDE) places Grajaú in a Macro-Zone of Environmental Protection and Recovery, requiring a special conservation focus that recognises the environmental fragility of the area and the presence of bodies of water with high biodiversity. The district is also a part of the Macro-Area of Reduction of Vulnerability and Environmental Recovery. This designation aims to promote Housing of Social Interest for families living in settlements located in environmentally protected areas close to bodies of water, prioritising resettlement resulting from an urbanisation plan or the evacuation of areas of risk and permanent preservation, in compliance with state legislation.

Ocupação Anchieta sits in land classified as a ZEIS 4 in the 2014 PDE (

Figure 7). The concept of a Special Zone of Social Interest, or ZEIS, was first developed at the local level in several capital cities in Brazil, almost 20 years before it was included in the Federal City Statute of 2001 (Law 10.257, Article 4, inc. V, line f). The ZEIS designation embodies the idea that the right to use the land can be legally recognised even when the right to property is absent. The goal of regularising the areas takes priority over the goal of eventually issuing legal titles over lands. There are two main types of ZEIS: those protecting existing informal and precarious settlements and those ensuring that a percentage of empty and underutilised land will be used in the future for affordable housing [

34]. These types are also known as occupied and vacant ZEISs, respectively [

35]. Thus, municipalities assign ZEIS designations not only to regularise informal settlements and illegal subdivisions but also to prevent land speculation and secure future land for low-income housing. In this context, a ZEIS 4 is considered a vacant ZEIS—unbuilt land, only suitable for future urbanisation, with socioenvironmental restrictions. The construction of social housing is possible following specific environmental controls. In São Paulo, ZEIS 4 sites are located in the area of protection in the watersheds of the Guarapiranga and Billings Reservoirs.

Compared with the map of Law 13.885/2004, the 2014 PDE increases by 23% the areas designated as ZEISs,

Figure 8 illustrates the ZEIS´ distribution and percentages in the city. With this provision, the 2014 Plan also stimulates the construction of social interest housing projects (Habitação de Interesse Social, HIS) or the popular housing market and allows for the construction of more flexible enterprises, provided these meet the needs of lower-income populations. ZEIS 4 sites include 80% of constructed areas for HIS 1 and 2, very-low- and low-income populations, and it is also possible to allocate a portion of the constructed area to other uses, such as small businesses and neighbourhood services. The vacant ZEIS sites zoned for affordable housing have been unable to attract significant private investment, and the government has been responsible for building most affordable units [

36].

An important consideration regarding the location of Ocupação Anchieta in a ZEIS 4 is that the land regularisation would probably benefit other families in need who are currently located in areas of geological risk in the Billings Watershed. As a result, the current residents in the occupation would be displaced. Again, the goal for a ZEIS 4 is planned social housing that respects the environment and does not include post-occupancy regularisation. As

Figure 9 shows, all the land reserved under this zoning type has been urbanised by formal or informal means over the last eight years. In São Paulo, only ZEIS 1 sites are characterised as occupied ZEISs suitable for land regularisation. Thus, we question the viability of ZEIS 4, especially its restrictions on post-occupancy regularization since the municipality lacks the capacity to monitor these areas and prevent new land occupations. Likewise, relocating the current vulnerable land occupiers to build social housing that would house newcomers from other risk areas in the watershed seems like a zero sum game.

6. The Repossession Court Case

On 26 August 2013, the nonprofit and landowner IAG, formerly called Ô Grupo Itápolis–Ação de Reintegração Social, took the land residents to court after the occupation of its 220,000 m2 property on 29 July 2013. The plaintiff’s complaint, a repossession suit with a motion for preliminary injunction, called for the immediate removal of land occupiers and their constructions and plantations. This lawsuit interrupted the five years of peaceful and uncontested possession of land required for Ocupação Anchieta residents to qualify for an adverse possession declaration, as established in Brazil’s Constitution and Federal Civil and Civil Procedure Codes. According to Article 183 of the Federal Constitution, for cases in which the landowner does not file a repossession claim, occupiers who possess an urban area of up to 250 m2 for five years, uninterrupted and without opposition, using it as housing for themselves or their family, acquire it as their domain as long as the claimant is not the owner of another urban or rural property. In this specific court case, IAG acted as the plaintiff and reported the occupation because it impacted their social and educational services for children and teenagers in the parcel.

From the very beginning, the case identified the environmental damage that the occupation produced, that is, a severe disturbance of the area of environmental protection along the bodies of water and the Atlantic Forest associated with it. In the lawsuit, the plaintiff explained how ‘invaders’ destroyed some of the dense existing vegetation, cutting and burning the forest. Consultation with the São Paulo State Public Prosecutor’s Office guided IAG’s decision to pursue the repossession case in order to prevent potential environmental crime sanctions against the Institute. The plaintiff’s initial claim addressed the following circumstances in detail: the initial occupation carried out by 20 people, the subsequent process of illegal land plotting, construction of sheds, fires, and targeted deforestation, and the progressive increase of families living on-site. The images in

Figure 10 illustrate the landowner’s documentation of the process of the occupation’s emergence and consolidation.

The letter of the law sides with landowners when an ‘invasion’ is recent. In fact, when the initial claim is substantiated by proper documentation and for cases in which the trespass and wrongful possession are recent, the trespasser will be summarily evicted. Otherwise, the land occupiers can remain in the occupied area until the merit of the case has been adjudicated. Thus, preliminary injunctions are common when the plaintiff of the repossession suit has properly documented his/her lawful possession. In this case, the judge granted the plaintiff’s request for repossession, ordering the presence of the police and authorising them to demolish the precarious dwellings without hearing the defendants, as the law allows. The court was unable to coordinate the serving of the repossession order to informal dwellers.

Soon after, the landowner and plaintiff, IAG, and the land occupiers formalised a mediated compromise to temporarily resolve the repossession claim without the eviction that the Judiciary Power homologated. The parties resolved a series of actions that included emptying the 54,000 m2 area for dedicated use of the Institute and enabling the occupiers to stay in the remaining 166,000 m2. Meanwhile, the Municipal Housing Authority would implement the My House, My Life program and initiate the reforestation of the site. However, by February 2015, IAG requested to proceed with the land repossession, ending the suspension of eviction. The conditions of agreement with the occupiers and the municipality had failed. In October 2015, for the first time in the case proceedings, the name of a resident appeared as a representative of the occupation dwellers. In fact, the defendants had never been summoned by a constable, and even at that time, the constable returned the court order to the judge once more, unable to enforce it.

Public defenders became involved in the case on 18 July 2016, almost three years after the case opened. Founded in 2006, the São Paulo Public Defender’s Office represents low-income citizens in a wide variety of legal proceedings, including eviction cases. In an interview with the Santo Amaro Office of Public Defenders, now representing the informal dwellers, we learned that they had informally spoken with the representative of the municipality about Ocupação Anchieta. Public defenders usually engage in land conflict mediation, and in this case they learned from the Municipal Housing Authority about the lack of resources for implementing the My House, My Life program on the site. Furthermore, due to additional environmental regulations on ZEIS 4 sites, even if the social housing program was implemented, it would not benefit the current dwellers but those city residents living in risk areas in the Billings Watershed. The public defenders reiterated that IAG had the right to evict the residents at any time. According to them, during the first five years of an occupation, land occupiers have no hope of tenure security in the courts if the property owner seeks repossession of the property. In these types of situations, public defenders try to negotiate with the landowner rather than provide the court with an answer to the plaintiff’s complaint. The public defenders in this case expressed the fear that contesting IAG’s complaint could accelerate the occupiers’ eviction.

After the failed attempts to fulfil the court order of repossession, IAG petitioned the judge to suspend the court case for 12 months, seeking an alternative agreement with residents for either a peaceful relocation or temporary individual contracts of permanency. In August 2016, the judge suspended the repossession case for a year. Although IAG expressed frustration with the court’s failure to fulfil the repossession order, they also hesitated to execute the land repossession by asking the judge three times to suspend the repossession order. The nonprofit understands that the evictions would undermine its own mission of attending to socially vulnerable families, so it engages in negotiations to define the terms of what it considers a temporary arrangement for the residents.

One of the requirements that IAG proposed in the negotiations was the need for measures to limit growth on the site by preventing occupation of the land by new arrivals. Furthermore, IAG required that the land occupiers respond to public prosecutors’ questions regarding environmental crimes related to the deforestation and occupation of parts of the APP on the site. The Brazilian Federal Constitution delegates to the Public Prosecutor’s Office the function of defending collective and diffuse rights, including the right to an ecologically balanced environment. In response to this issue, Ocupação Anchieta residents removed 141 shacks originally sitting in the APP area buffer zone by early 2018). The images in

Figure 11 illustrate the conditions of the APP, the occupant-led demolition of the homes in the buffer area, and the prototypes of their new homes.

In August 2017, at the end of the one-year suspension, IAG presented to the residents a resolution involving two main components. First, in the case of an individual comodato (commodatum), each land occupier must sign a contract with IAG for the use of the land, without any rights listed on it and renewable every year. The comodato also includes specific references to the management of waste and recycling, as well as to the urgent need to address sewage and sanitation issues. The proposed resolution envisions a free commodatum for each resident, as well as a second lease agreement with the Ocupação Anchieta Association, according to which the Association is responsible for collecting a fee from its members, including all residents, on behalf of IAG.

At the same time, IAG petitioned the judge to concede the suspension of the court case for another 60 days whilst waiting for an agreement to be formalised at the community assembly that would take place in December 2017. The assembly never took place, according to our communications with both parties in the case. There is no subsequent entry in the case until July 2018, when the judge gave IAG five days to take action or she would extinguish the lawsuit due to negligence of the parties and neglect of the plaintiff to act with reasonable diligence. This was the last procedural step that the authors followed.

7. Discussion

Far from being resolved, Ocupação Anchieta represents a relevant case study of the many challenges associated with the materialisation of constitutional provisions to ensure the social and ecological functions of private urban property. The previous sections explained the limited prospects for land regularisation and tenure security faced by land occupations in ZEIS 4 sites in the city of São Paulo. The same constraints apply to landowners who have prospects of development limited by regulations. Therefore, it is common for landowners who own more than one property to welcome expropriation via eminent domain, if the municipal government decides to implement low-density social housing to relocate those living in areas of risk, as the 2014 São Paulo Master Plan foresees. Interviews with leaders of nationwide housing movements and lawyers defending informal dwellers reveal that it is not uncommon for landowners to be willing to negotiate with the government and with neighbourhood associations in order to suspend repossession suits until there is certainty of compensation for the land. For instance, property in the extreme periphery or property with development restrictions becomes less valued and profitable. Nonetheless, the landowning institution in this particular lawsuit has different motivations, given its philanthropic nature.

The conflict that resulted in the Repossession Lawsuit initiated in 2013 involved many public sector actors in different capacities—public representatives from Capela do Socorro Subprefecture and the municipal department of housing’s mediator for land conflicts, as well as large metropolitan utility companies, such as Sanitation Utility, the Metropolitan Company of Waters and Energy and Electricity, the Metropolitan Military Police, and the Community Councils for Public Security (Conselhos Comunitários de Segurança, Conseg)—to address community relationships. These entities assessed the on-site infrastructure and explored the possibility of providing settlement upgrading in the future. There were three actors from the judicial system: the civil court judges assigned to the case over time; São Paulo public defenders, who represented the residents in the legal proceedings against eviction; and the public prosecutors, who are responsible for addressing the diffuse and collective rights pertaining to land use disputes involving informal parcelling in environmentally protected areas.

Currently, negotiations on the case continue. The dwellers at Ocupação Anchieta are directly or indirectly connected to a large network of urban agents who have supported them at different stages in the process. The residents formally established the Ocupação Anchieta Neighbourhood Association with the goal of obtaining the legal and political recognition required to acquire municipal infrastructure and services. The Association plays an important role in obtaining support for Ocupação Anchieta from outside parties, such as public defenders and other housing and human rights organisations offering support. The residents also receive support from various public entities that address educational, social, and health needs, as well as from a labour union and academic institutions. In the last few months, the Ocupação Anchieta Association has been active in connecting with other housing movements in the city as a means of addressing the complexities of the legal case, which continue to threaten the dwellers’ right to stay in place. This growing social capital, which was not present at the beginning of the case, is important for the dwellers in their continuing struggle to gain the right of housing.

In summary, informal dwellers’ lack of tenure security is not only derived from the repossession suit filed by the landowner, but also from municipal provisions for ZEIS 4 parcels to build future low-income homes for vulnerable families currently living in risk areas in the Billings Watershed. Meanwhile, the settlement continues to develop without the input of municipal urban planners and architects. Residents have proceeded to develop the site, making decisions about the location and number of streets, sewage, density, and community facilities. Informal dwellers’ site-planning decisions have been shaped by their own construction experience and knowledge of informal connections to water, sewage, and electricity lines. Residents’ interactions with the landowner, public servants and legal actors responsible for environmental oversight, NGOs, and two foreign universities have enhanced their knowledge about the ecological functions of watersheds, waste management practices, site pollution, and deforestation. As a result, informal dwellers have changed some of their site development practices to minimise their environmental impact. Although the discourse on environmental protection has been evoked in the repossession suit, no studies of the remaining ecological functions of the site have been produced. Nonetheless, the fear of committing and bearing the responsibility for an environmental crime has guided the practice of both the plaintiff and the defendant, contributing to an increased awareness of the interactions between the built and natural environments.

Unfortunately, planners did not contribute their expertise to address the interface of informal housing and the environment. The primacy of private property rights during the first five years of a land occupation prevents planners and architects from devising techniques for sustainable informal settlement development. Municipal support for guidance on sustainable practices would have diminished pollution as well as improved the health of residents. Repossession cases are time consuming, either because the courts cannot coordinate their constables with the police and municipal department in order to enforce repossession orders or because the private land occupied for the purpose of housing has limited market value, so landowners hesitate to act diligently on lawsuits. Meanwhile, informal dwellers move the settlements towards consolidation without the proper input of city planners.

Globally, planning scholars have recognized the importance of investigating land use and environmental conflicts in order to understand the circumstances under which consensus building [

37,

38] and collaborative planning [

39,

40] can produce positive planning outcomes. Additionally, research has even documented the generative and creative potential of conflicts [

41]. In 2005, the Brazilian Federal government established a land conflict prevention and mediation working group under the Ministry of Cities’ Deliberative and Participatory Council. The working group advised on existing land conflicts and produced a national policy for the topic [

42]. Nonetheless, much more work needs to be accomplished in terms of conflict identification and anticipation [

17]. In the case of São Paulo’s municipal government, an investigation of how environmental and housing rights conflicts develop in courts and outside them can help to anticipate and plan for these disputes in young land occupations. Setting unrealistic expectations that land occupations in areas of environmental protection will cease because the zoning does not support them is not sustainable. Acknowledging stakeholders’ common interests and making zoning regulations more suitable for the urban periphery could open the opportunity for timely municipal support for young land occupations.

8. Conclusions

Brazil’s Federal Constitution establishes the social function of private property and recognises housing as a basic right, further empowering the municipal government through City Statute provisions. At the same time, the protection of the environment is considered a basic constitutional right, aside from the enactment of enabling legislation to implement the social function of urban property. As McAllister points out, legal systems have built a robust environmental enforcement capacity in recent decades. This study’s findings demonstrate that despite the innovations in constitutional and infra-constitutional guarantees for informal dwellers, the right to private property still prevails over the right to housing as far as young land occupations are concerned. We observed that it is very difficult for the settlers in young land occupations to secure adequate shelter and tenure in their first few years.

By focusing on the specific case of Ocupação Anchieta, a young land occupation, we examine the role of legal institutions in mediating the urban land conflicts involving the environmental and social functions of private property protection and informal settlements. Investigating a young land occupation sheds light on the many challenges residents must face in the early years. Together with the precarious conditions of their homes and the rudimentary infrastructure systems they can afford to implement, they face a complex situation: on one hand, the convenience of remaining invisible for five years, and on the other, the desperate need for legal and social support that forces them to reach out and expand their social network. In these initial years, there is little assistance, if any, from the municipality, exacerbating the environmental impact and social vulnerability of the residents. When the land occupation takes place on private land, additional legal provisions further complicate the struggle to gain right to the city.

Legal actors, such as judges and public defenders, attempt to manage and mediate conflicts between the rights of land occupiers, property owners, and diffuse environmental protection provisions, yet private property rights triumph in the early years of a land occupation. Municipal planners currently do not assist in planning these younger occupations, fearing legal repercussions because of their uncertain tenure status. Although city planners attempt to mediate land conflicts, they rarely develop strategies to improve a young occupation. Our investigation sheds light on these lawsuits and court-driven conflict resolution meetings in order to proactively devise socially and environmentally sustainable mechanisms for working with young land occupations. Court cases are a good source of data for the identification of land use conflicts and the examination of legal arguments by the parties [

18]. Together with the cases, current efforts to identify land use conflicts that may result in the eviction of informal dwellers in São Paulo involve the residents and local groups working with them in collaboration with academic institutions. A good example is the Eviction Lab (Observatório de Remoções, at LabCidade), a collaboration of universities working on this issue [

43].

By conducting a multiyear, in-depth case study of a legal conflict of a young informal land occupation on private property, we discuss the larger role planners could play in anticipating and mediating conflicts between landowners, land occupiers, and the environment. In so doing, our work reveals the limitations of current planning regulations in stewarding more sustainable practices of urbanisation in the periphery of the city. Therefore, consideration of conflict anticipation [

17] can better realise the socioecological functions of urban property.

This case study of Ocupação Anchieta raises the question of whether private property interests remain invulnerable or difficult to challenge. As the case illustrates, private property rights continue to have uncontested power in the legal system, and the five-year provision required to enable adverse possession remains difficult to attain for informal communities. Even though private property prevails over environmental and social rights, at least during the first five years of an informal occupation, the lack of coordination between courts, the police, and municipal governments, aligned with the low price of land in environmentally protected areas, reduces the speed with which, and even the likelihood that, families will be displaced. During this time of limbo, residents continue to develop their settlements through precarious means, jeopardising both their health and that of the environment. As the case of Ocupação Anchieta shows, better channels of communication between municipal departments, the courts, public defenders (who joined the case only three years after it began), and the landowner could facilitate the prospects of a timely agreement. Ironically, even the landowner who filed the Repossession Suit would have preferred an alternative solution that would keep informal dwellers on the land.

Cities in the Global South continue to grow rapidly through new informal settlements in their peripheries, reducing open space in the form of either agricultural or environmentally protected land. Nonetheless, most of the planning attention devoted to informal settlements takes place at later stages of their development. Legal disputes over tenancy and tenure security prevent municipal governments and development agencies from investing in very young land occupations. Like our case study of Ocupação Anchieta, our ongoing research in three other younger occupations in São Paulo demonstrates that this is a missed opportunity for the planning profession to work in an anticipatory manner. Local zoning and master planning could incorporate earlier planning support to minimise the environmental impact of occupations and ensure access to basic services so that young land occupations can establish more sustainable practices of urbanisation from the early stages of their implementation.