Understanding Perceptions of the Bioeconomy in Austria—An Explorative Case Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- How is the political vision of a future “bioeconomy” perceived on societal levels in Austria?

- (2)

- What expectations, or fears arise and are associated with the vision of a bioeconomy?

- (3)

- What tendencies or phenomena can be observed in relation to these fears or expectations?

- (4)

- How are these expectations and fears linked with ethical consumption behaviour?

2. Theoretical Background

- (1)

- a biotechnology vision, which focuses on technological implementations;

- (2)

- a bioresource vision, which tries to enhance the application of raw materials through research, development and demonstration; and

- (3)

- a bioecology vision, which seeks to promote change in regional processes and systems to improve the usage of resources.

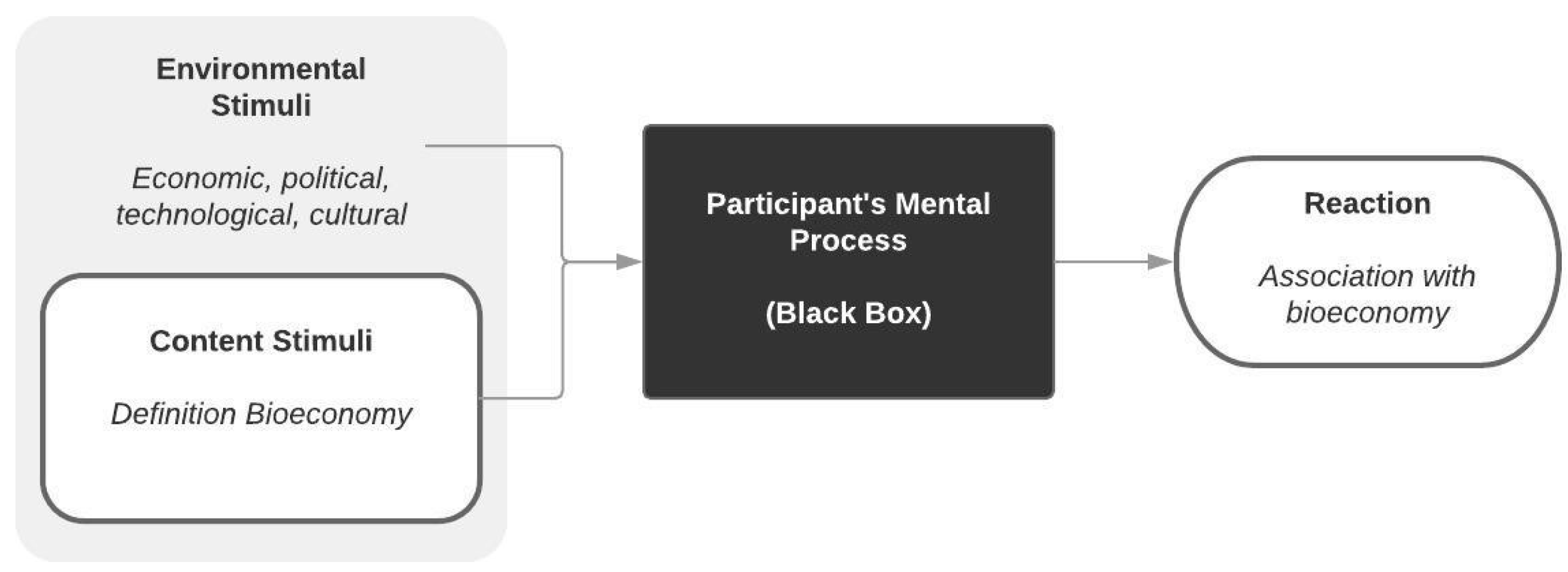

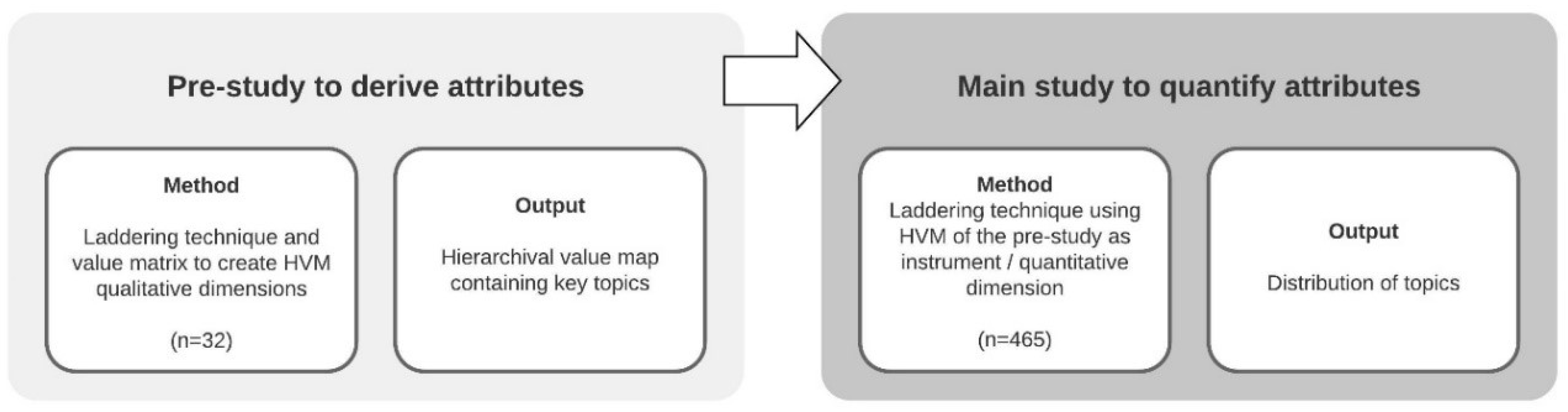

3. Material and Methods

3.1. Research Design

3.2. Pre-Study

3.3. Main Study

4. Results

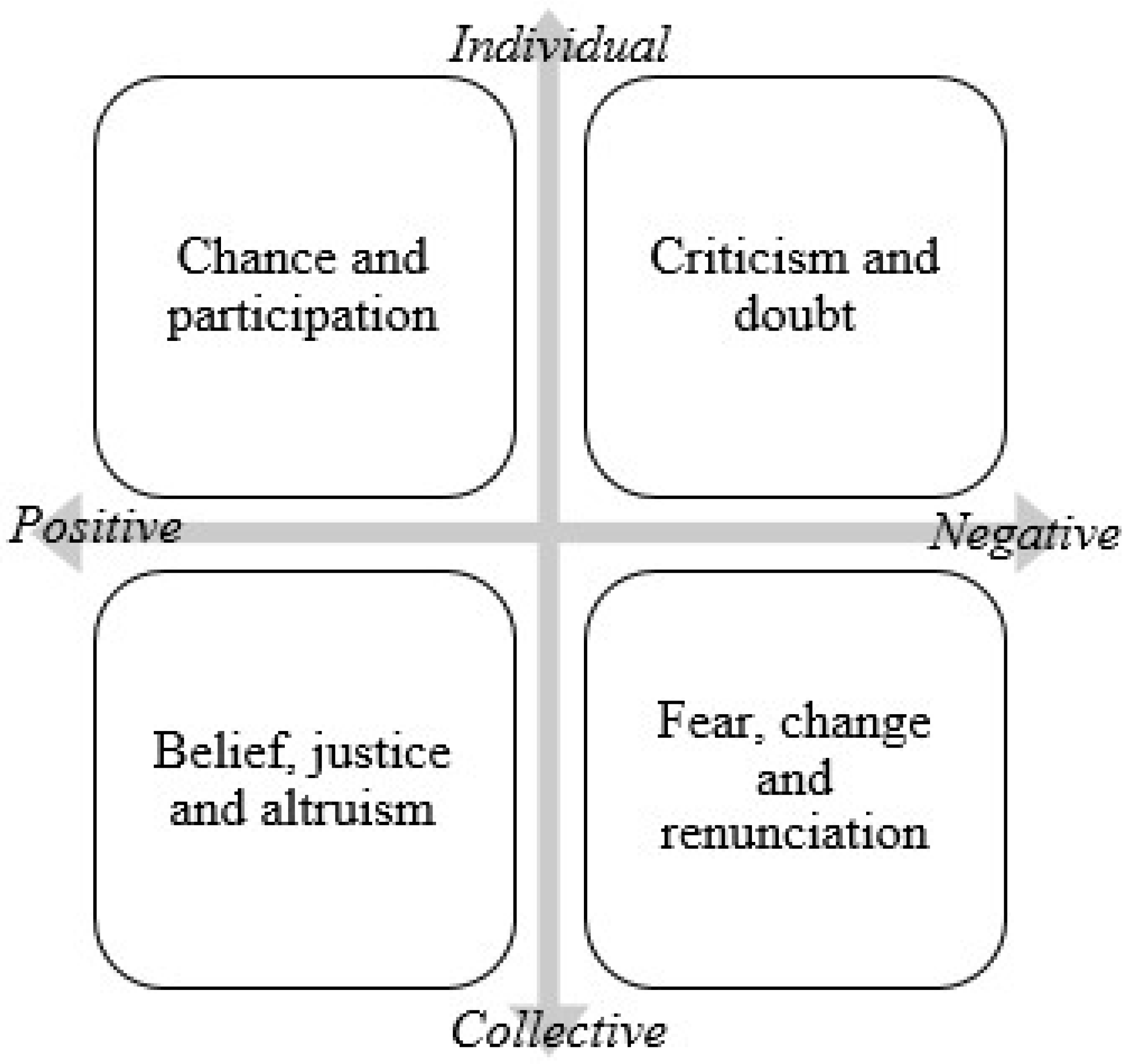

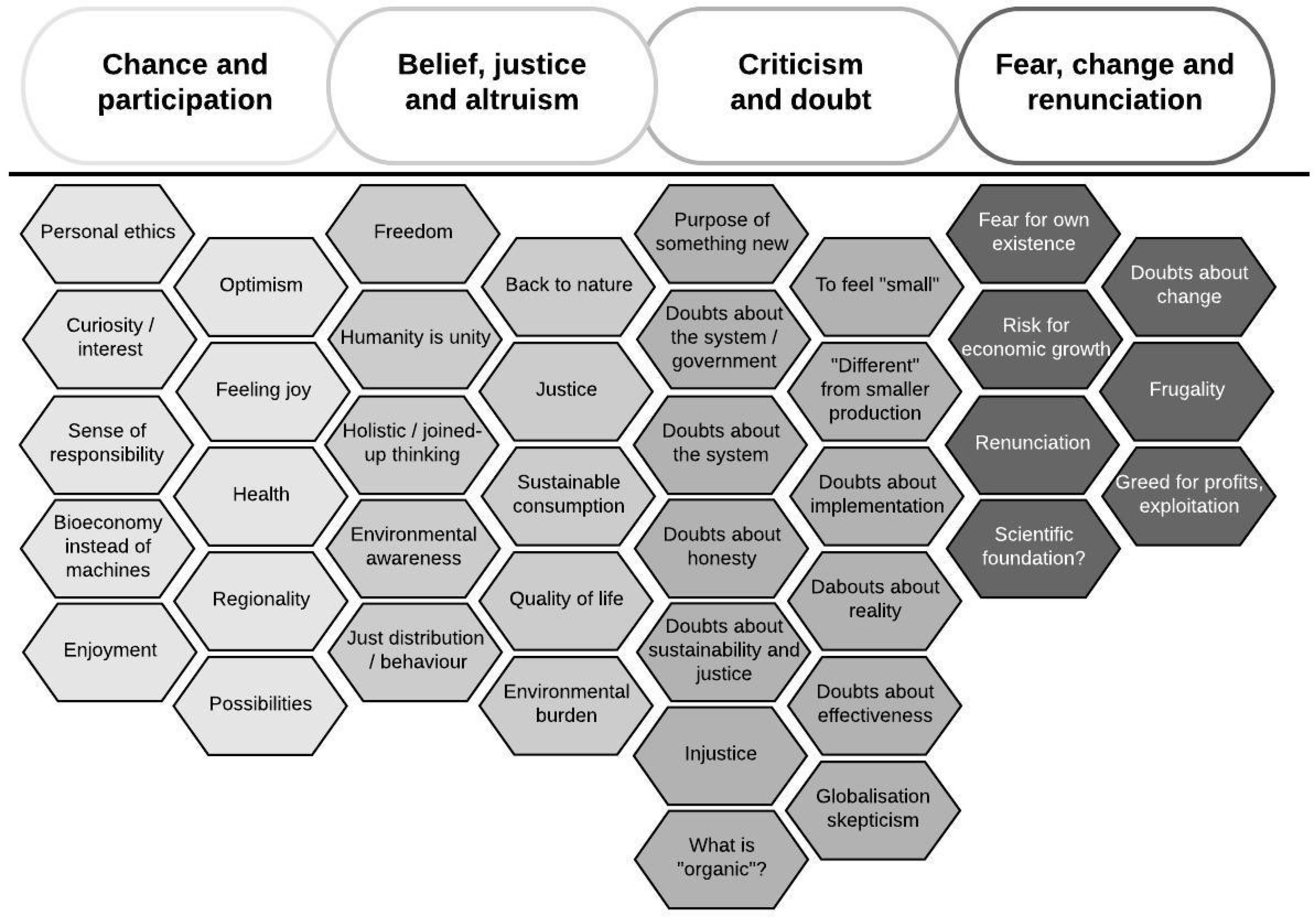

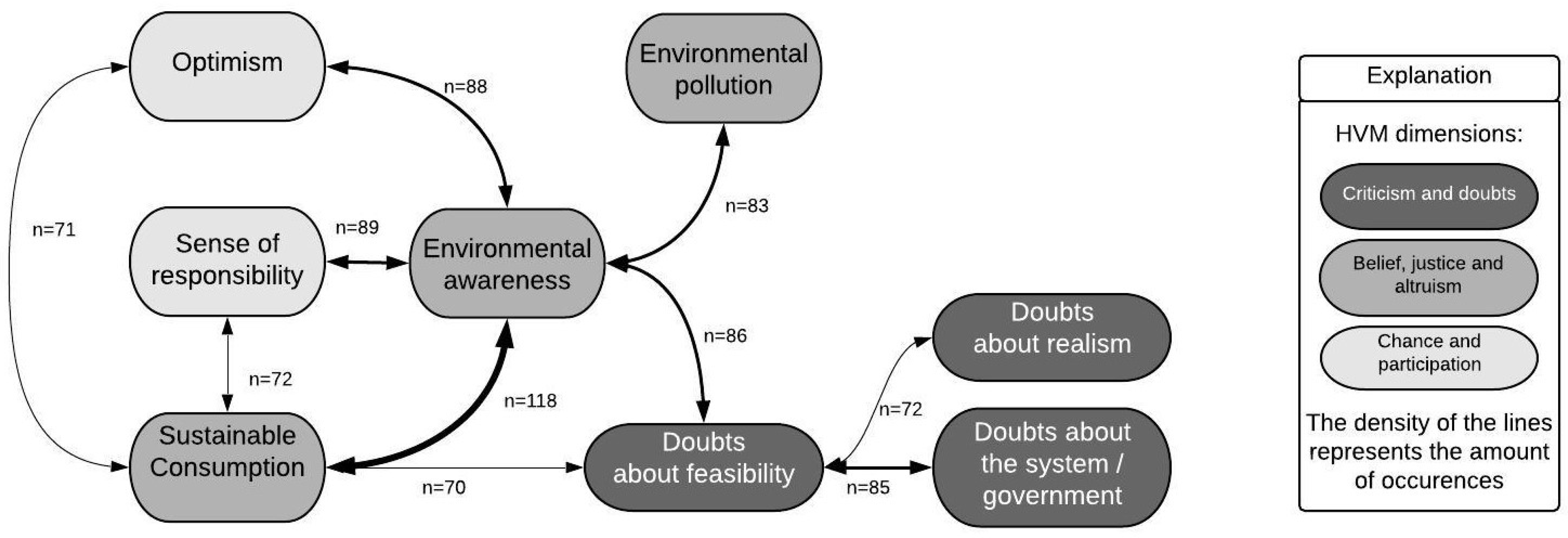

4.1. Pre-Study: The Hierarchical Value Map

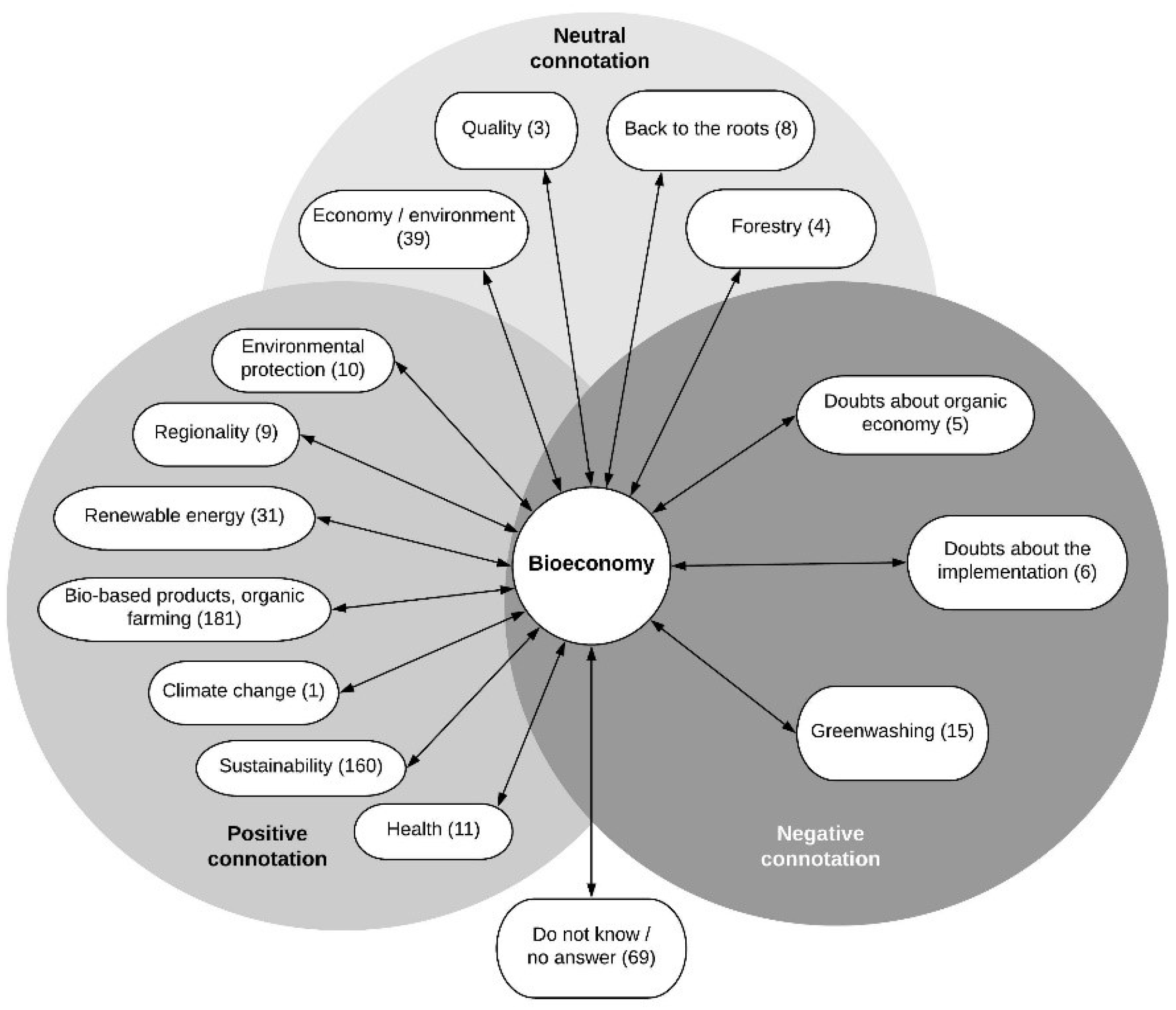

4.2. Main Study: First Associations with the Term “Bioeconomy

4.3. Attributes of the HVM

4.4. Attributes of the HVM by Different Societal Groups

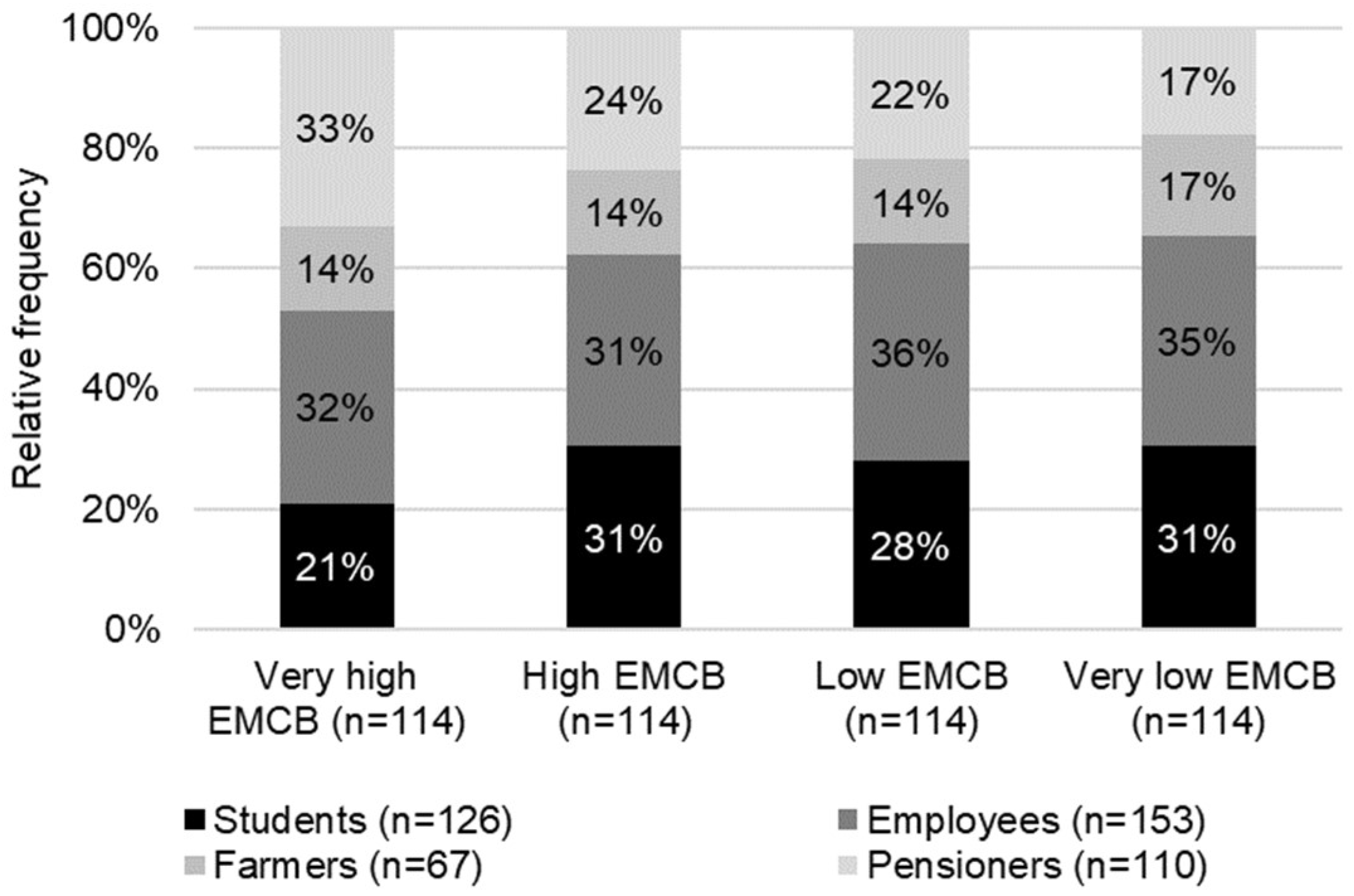

4.5. Attributes of the HVM by Sustainability Groups

4.6. Attitude Chain

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

- The feasibility of a future bioeconomy is identified as the most critical aspect. Therefore, communication needs to focus on transferring examples that demonstrate the possibilities, potential and realities of a bioeconomy.

- Sustainable consumption was mentioned as an important topic of bioeconomy by the participants, a result that needs further exploration. This issue could be of particular interest when creating an inclusive bioeconomy, since it calls for the active involvement of consumers.

- Highly educated, young adults like students present a constructive target group for discussions on bioeconomy with regard to communications. In contrast, the employees’ and farmers’ perceptions were observed to be overshadowed by personal fears and concerns about the risks associated with change.

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Data Availability

References

- European Commission. Innovating for Sustainable Growth: A Bioeconomy for Europe; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2012.

- Aguilar, A.; Wohlgemuth, R.; Twardowski, T. Perspectives on bioeconomy. New Biotechnol. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staffas, L.; Gustavsson, M.; McCormick, K. Strategies and policies for the bioeconomy and bio-based economy: An analysis of official national approaches. Sustainability 2013, 5, 2751–2769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, J. Production, consumption and the world summit on sustainable development. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2003, 5, 63–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Besi, M.; McCormick, K. Towards a bioeconomy in Europe: National, regional and industrial strategies. Sustainability 2015, 7, 10461–10478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, R. Bioeconomy Strategies: Contexts, Visions, Guiding Implementation Principles and Resulting Debates. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugge, M.M.; Hansen, T.; Klitkou, A. What is the bioeconomy? A review of the literature. Sustainability 2016, 8, 691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausknost, D.; Schriefl, E.; Lauk, C.; Kalt, G. A Transition to Which Bioeconomy? An Exploration of Diverging Techno-Political Choices. Sustainability 2017, 9, 669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinschmit, D.; Arts, B.; Giurca, A.; Mustalahti, I.; Sergent, A.; Pülzl, H. Environmental concerns in political bioeconomy discourses. Int. For. Rev. 2017, 19, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramcilovic-Suominen, S.; Pülzl, H. Sustainable development–A ‘selling point’of the emerging EU bioeconomy policy framework? J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 172, 4170–4780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. The Bioeconomy to 2030: Designing a Policy Agenda; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, K.; Knierim, A. Bioökonomie und der Mensch. Boil. Unserer Zeit 2012, 42, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupont-Inglis, J.; Borg, A. Destination bioeconomy–The path towards a smarter, more sustainable future. New Biotechnol. 2017, 40 Pt A, 140–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCormick, K.; Kautto, N. The bioeconomy in Europe: An overview. Sustainability 2013, 5, 2589–2608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustalahti, I. The responsive bioeconomy: The need for inclusion of citizens and environmental capability in the forest based bioeconomy. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 30, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinschmit, D.; Pülzl, H.; Secco, L.; Sergent, A.; Wallin, I. Orchestration in political processes: Involvement of experts, citizens, and participatory professionals in forest policy making. For. Policy Econ. 2018, 89, 4–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luchs, M.G.; Naylor, R.W.; Irwin, J.R.; Raghunathan, R. The Sustainability Liability: Potential Negative Effects of Ethicality on Product Preference. J. Mark. 2010, 74, 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarlat, N.; Dallemand, J.F.; Monforti-Ferrario, F.; Nita, V. The role of biomass and bioenergy in a future bioeconomy: Policies and facts. Environ. Dev. 2015, 15, 3–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I.; Fishbein, M. Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behaviour; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Chin, H.C.; Choong, W.W.; Wan Alwi, S.R.; Mohammed, A.H. Issues of social acceptance on biofuel development. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 71, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araki, M.; Ishii, T. Towards social acceptance of plant breeding by genome editing. Trends Plant Sci. 2015, 20, 145–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sijtsema, S.J.; Onwezen, M.C.; Reinders, M.J.; Dagevos, H.; Partanen, A.; Meeusen, M. Consumer perception of bio-based products—An exploratory study in 5 European countries. NJAS—Wagen. J. Life Sci. 2016, 77, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, T.; Ranacher, L.; Mair, C.; Berghäll, S.; Lähtinen, K.; Forsblom, M.; Toppinen, A. Perceptions on the Importance of Forest Sector Innovations: Biofuels, Biomaterials, or Niche Products? Forests 2018, 9, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranacher, L.; Höfferer, K.; Lettner, M.; Hesser, F.; Stern, T.; Rauter, R.; Schwarzbauer, P. What would potential future opinion leaders like to know? An explorative study on the perceptions of four wood-based innovations. J. Land Manag. Food Environ. 2018, 69, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boehlje, M.; Bröring, S. The Increasing Multifunctionality of Agricultural Raw Materials: Three Dilemmas for Innovation and Adoption. Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 2011, 14, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Klerck, D.; Sweeney, J.C. The effect of knowledge types on consumer-perceived risk and adoption of genetically modified foods. Psychol. Mark. 2007, 24, 171–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbeke, W. Consumer attitudes toward genetic modification and sustainability: Implications for the future of biorenewables. Biofuels Bioprod. Biorefin. 2007, 1, 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, D.H.; Klaassen, P.; Broerse, J.E. Unraveling Dutch citizens’ perceptions on the bio-based economy: The case of bioplastics, bio-jetfuels and small-scale bio-refineries. Ind. Crops Prod. 2017, 106, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skipper, D.; Van de Velde, L.; Popp, M.; Vickery, G.; Van Huylenbroeck, G.; Verbeke, W. Consumers’ perceptions regarding tradeoffs between food and fuel expenditures: A case study of US and Belgian fuel users. Biomass Bioenergy 2009, 33, 973–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotler, P. Marketing management: The millennium edition. Mark. Manag. 2000, 23, 188–193. [Google Scholar]

- McGuire, W.J. Some internal psychological factors influencing consumer choice. J. Consum. Res. 1976, 2, 302–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief, Attitude, Intention, and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research; Addison-Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Kanagal, N. An Extended Model of Behavioural Process in Consumer Decision. Int. J. Mark. Stud. 2016, 8, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, T.J.; Gutman, J. Laddering Theory—Method, Analysis and Interpretation. J. Advert. Res. (JAR) 1988, 28, 11–31. [Google Scholar]

- Gengler, C.; Klenosky, D.; Mulvey, M. Improving the graphic representation of means-end results. Int. J. Res. Mark. 1995, 12, 245–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, J.; Ranacher, L.; Stern, T.; Schwarzbauer, P. Forest management or greed of gain? An information experiment on peri-urban forest visitors’ attitudes regarding harvesting operations. Urban For. Urban Green. 2017, 27, 214–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vannoppen, J.; Verbeke, W.; Van Huylenbroeck, G. Consumer value structures towards supermarket versus farm shop purchase of apples from integrated production in Belgium. Br. Food J. 2002, 104, 828–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begusch-Pfefferkorn, K.; Ulrich, H.; Stockhammer, A.; Ganglberger, E.; Fuhrmann, E.; Silmbrod, A.; Stangl, R.; Matzer, C. Klimawandel und Ressourcenknappheit (Hg). In Bericht: Bioökonomie und FTI-Aktivitäten in Österreich, ein Beitrag zur Bioökonomie-Entwicklung der Bundesregierung; FTI-AG2, Klimawandel und Ressourcenknappheit, BMFLUW, BMVIT, BMWFW: Wien, Austria, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Vringer, K.; Aalbers, T.; Blok, K. Household energy requirement and value patterns. Energy Policy 2007, 35, 553–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudbury-Riley, L.; Kohlbacher, F. Ethically minded consumer behavior: Scale review, development, and validation. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 2697–2710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics Austria. Register Census 2011 Coordinated Labour Force Statistics 2009, 2018, 2010, 2012 to 2016, Each with Cut-Off Date 31.10. Territorial Status 2016. Created on 19 September 2018. 2018. Available online: http://www.statistik.at/web_de/statistiken/menschen_und_gesellschaft/bevoelkerung/volkszaehlungen_registerzaehlungen_abgestimmte_erwerbsstatistik/pendlerinnen_und_pendler/index.html (accessed on 31 October 2018).

- Hansen, L.; Bjørkhaug, H. Visions and Expectations for the Norwegian Bioeconomy. Sustainability 2017, 9, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nähyä, A. Transition in the Finnish forest-based sector: Company perspectives on the bioeconomy, circular economy and sustainability. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Pfau, S.; Vos, J.; Dammer, L.; Arendt, O. Public Perception of Bio-Based Products—Deliverable 2.2. Roadmap for the Chemical Industry in Europe towards a Bioeconomy. 2017. Available online: https://www.roadtobio.eu/uploads/publications/deliverables/RoadToBio_D22_Public_perception_of_bio-based_products.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2018).

- Hodge, D.; Brukas, V.; Giurca, A. Forests in a bioeconomy: Bridge, boundary or divide? Scand. J. For. Res. 2017, 32, 582–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- German Bioeconomy Council. Bioeconomy Policy: Synopsis and Analysis of Strategies in the G7; A Report from the German Bioeconomy Council; Office of the Bioeconomy Council: Berlin, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

| Modules | Questions |

|---|---|

| First association: “the starter question” | What do you associate the term “bioeconomy” with? |

| Stimulus | A bioeconomy is a type of economy that relies on renewable natural resources to provide food, energy, products and services. It can contribute to a reduction in our dependence on fossil fuels, to the development of innovation and economy and to the creation of new jobs. |

| Reaction (Module 1) | After you heard the definition of the bioeconomy, I would like to know your thoughts on the bioeconomy.Why is this aspect important to you? (follow-up questions using Laddering Technique) |

| Attitude towards sustainable consumption (Module 2) | If I have the choice, I choose the product with the lowest environmental impact. |

| Because of environmental issues, I have already switched to another product. | |

| I do not buy a product if I know something about the potential environmental impacts. | |

| I do not buy household products if they have negative impacts on the environment. | |

| If possible, I buy products that are packaged in reused or recycled material. | |

| I try to buy paper products made of recovered paper. | |

| I do not buy a product if I know that the producing firm acts in a socially irresponsible way. | |

| I do not buy products from firms if I know that they have been produced under poor labour conditions. | |

| In spite of cheaper alternatives, I paid more for environmentally friendly products. | |

| In spite of cheaper alternatives, I paid more for socially responsible products. |

| Target Group | Total | Women | Median Age | Living in Rural Area | A-Levels or Higher Level of Education | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Students | 126 | 28 | 64 | 51 | 25 | 58 | 46 | 121 | 96 |

| Employees | 153 | 33 | 53 | 35 | 34 | 93 | 61 | 106 | 69 |

| Farmers | 67 | 15 | 33 | 49 | 33 | 44 | 66 | 48 | 72 |

| Pensioners | 110 | 24 | 52 | 47 | 66 | 52 | 47 | 53 | 48 |

| Sum/average | 456 | 100 | 202 | 45 | 33 | 247 | 54 | 328 | 71 |

| Value Dimensions | Attributes | Absolute Frequency | Relative Frequency |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chance and participation | Optimism | 152 | 33% |

| Sense of responsibility | 130 | 29% | |

| Regionalism | 123 | 27% | |

| Possibilities | 101 | 22% | |

| Curiosity/interest | 107 | 23% | |

| Personal ethics | 85 | 19% | |

| Enjoyment | 19 | 4% | |

| Health | 75 | 16% | |

| Bioeconomy instead of machines | 31 | 7% | |

| Belief, equity and altruism | Environmental awareness | 209 | 46% |

| Sustainable consumption | 175 | 38% | |

| Environmental pollution | 122 | 27% | |

| Back to nature | 106 | 23% | |

| Quality of life | 71 | 16% | |

| Fair distribution | 65 | 14% | |

| Joined-up thinking | 66 | 14% | |

| Equity | 53 | 12% | |

| Humanity as unity | 28 | 6% | |

| Renewable energy vs. fossil fuels | 22 | 5% | |

| Critics and doubts | Doubts about feasibility | 199 | 44% |

| Doubts about the system/government | 140 | 31% | |

| Doubts about realism | 105 | 23% | |

| Doubts about effectiveness | 75 | 16% | |

| Doubts about honesty | 72 | 16% | |

| Doubts about sustainability and equity of a bioeconomy | 70 | 15% | |

| What is the meaning of “organic”? | 48 | 11% | |

| Sense of something new? | 49 | 11% | |

| Inequity | 50 | 11% | |

| Scepticism towards globalization | 42 | 9% | |

| Unclear future/necessity | 27 | 6% | |

| Unclear definition | 25 | 5% | |

| “Be different” with a small production | 23 | 5% | |

| Fear, change and renunciation | Doubts about transformation | 97 | 21% |

| Exploitation | 70 | 15% | |

| Frugality | 49 | 11% | |

| Renunciation | 42 | 9% | |

| Jobs | 40 | 9% | |

| Hindering economic welfare | 38 | 8% | |

| Costs | 38 | 8% | |

| Scientific foundation? | 28 | 6% | |

| Fear for own existence | 24 | 5% |

| Laddering Theme | Target Group | χ2(df) | p Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Students (n = 126) | Employees (n = 153) | Farmers (n = 67) | Pensioners (n = 110) | |||

| Curiosity/interest | 34.92% | 20.26% | 22.39% | 15.45% | χ2(3) = 14.055 | 0.002 |

| Back to nature | 15.08% | 18.30% | 34.33% | 32.73% | χ2(3) = 16,961 | 0.001 |

| Quality of life | 8.73% | 17.65% | 11.94% | 22.73% | χ2(3) = 9944 | 0.016 |

| Doubts about sustainability and equity of a bioeconomy | 8.73% | 15.69% | 26.87% | 15.45% | χ2(3) = 14,896 | 0.009 |

| Doubts about effectiveness | 16.67% | 10.46% | 31.34% | 15.45% | χ2(3) = 11,101 | 0.002 |

| Inequity | 5.56% | 10.46% | 20.90% | 11.82% | χ2(3) = 10,667 | 0.012 |

| Fear for own existence | 0.00% | 9.80% | 7.46% | 3.64% | χ2(3) = 14,561 | 0.002 |

| Attributes | Level of EMCB | χ2(df) | p-Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Very High EMCB (n = 114) | High EMCB (n = 114) | Low EMCB (n = 114) | Very Low EMCB (n = 114) | |||

| Optimism | 45% | 32% | 32% | 25% | χ2(3) = 10.816 | 0.013 |

| Sense of responsibility | 41% | 29% | 19% | 25% | χ2(3) = 14.676 | 0.002 |

| Health | 23% | 9% | 16% | 18% | χ2(3) = 8.601 | 0.036 |

| Justice | 18% | 14% | 9% | 6% | χ2(3) = 8.775 | 0.032 |

| Sustainable Consumption | 44% | 45% | 36% | 29% | χ2(3) = 7.966 | 0.047 |

| Quality of life | 25% | 17% | 12% | 8% | χ2(3) = 14.597 | 0.002 |

| Doubts on realism | 16% | 23% | 22% | 32% | χ2(3) = 8.154 | 0.043 |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Stern, T.; Ploll, U.; Spies, R.; Schwarzbauer, P.; Hesser, F.; Ranacher, L. Understanding Perceptions of the Bioeconomy in Austria—An Explorative Case Study. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4142. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10114142

Stern T, Ploll U, Spies R, Schwarzbauer P, Hesser F, Ranacher L. Understanding Perceptions of the Bioeconomy in Austria—An Explorative Case Study. Sustainability. 2018; 10(11):4142. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10114142

Chicago/Turabian StyleStern, Tobias, Ursula Ploll, Raphael Spies, Peter Schwarzbauer, Franziska Hesser, and Lea Ranacher. 2018. "Understanding Perceptions of the Bioeconomy in Austria—An Explorative Case Study" Sustainability 10, no. 11: 4142. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10114142

APA StyleStern, T., Ploll, U., Spies, R., Schwarzbauer, P., Hesser, F., & Ranacher, L. (2018). Understanding Perceptions of the Bioeconomy in Austria—An Explorative Case Study. Sustainability, 10(11), 4142. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10114142