Transition Management for Improving the Sustainability of WASH Services in Informal Settlements in Sub-Saharan Africa—An Exploration

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Case Studies

2.2. Research Approach

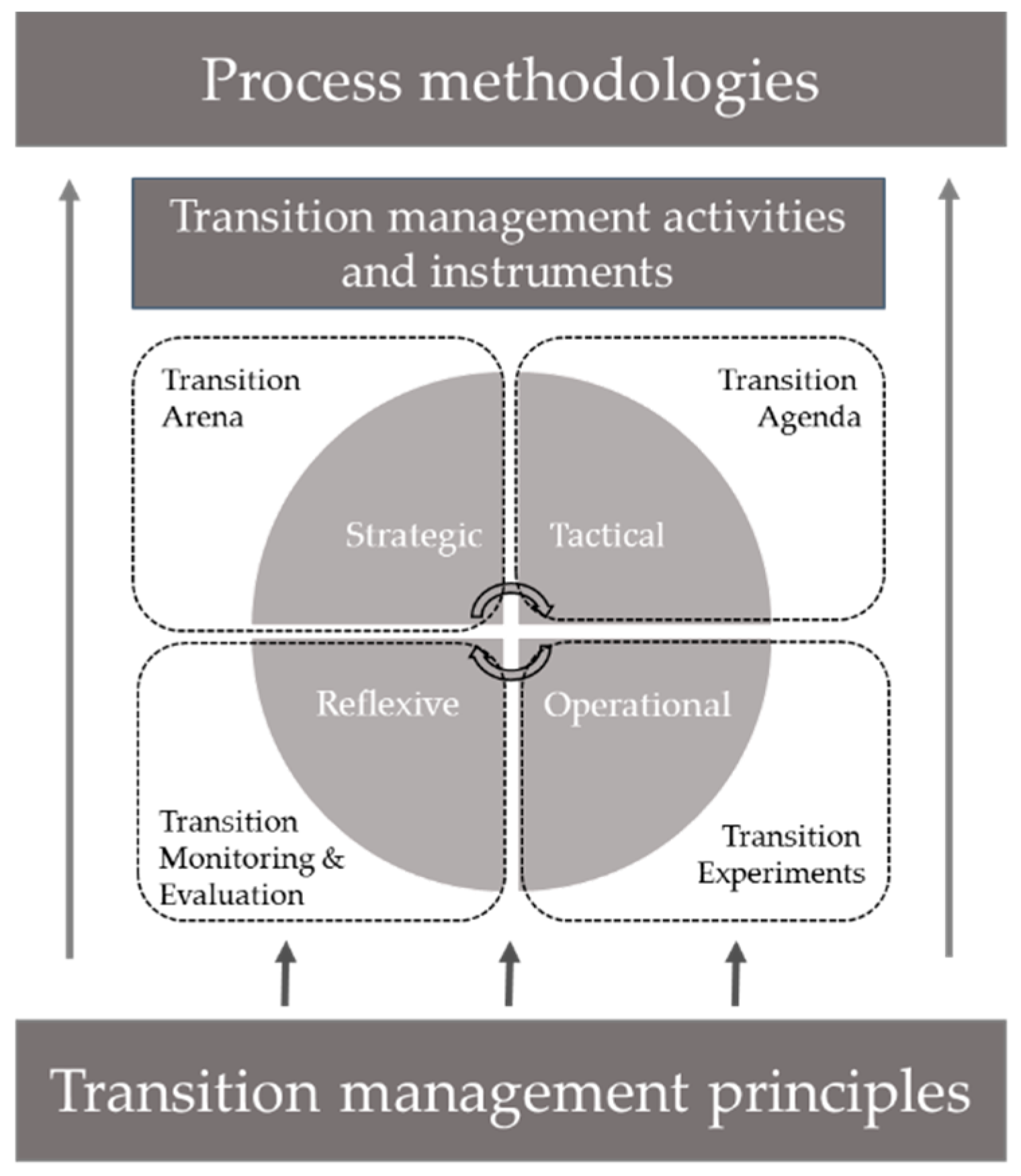

3. Transition Management

4. Conceptual and Application Challenges for Transition Management in Sub-Saharan Africa

4.1. Multiplicity of WASH Practices, Structures and Arrangements

4.2. Governance Capacities for WASH Services and Maintenance

4.3. Landownership for Sustainable Access to WASH

4.4. Public Participation in Decision-Making Related to WASH

4.5. Socio-Economic Inequalities Governing Access to WASH

4.6. Conceptual and Application Challenges

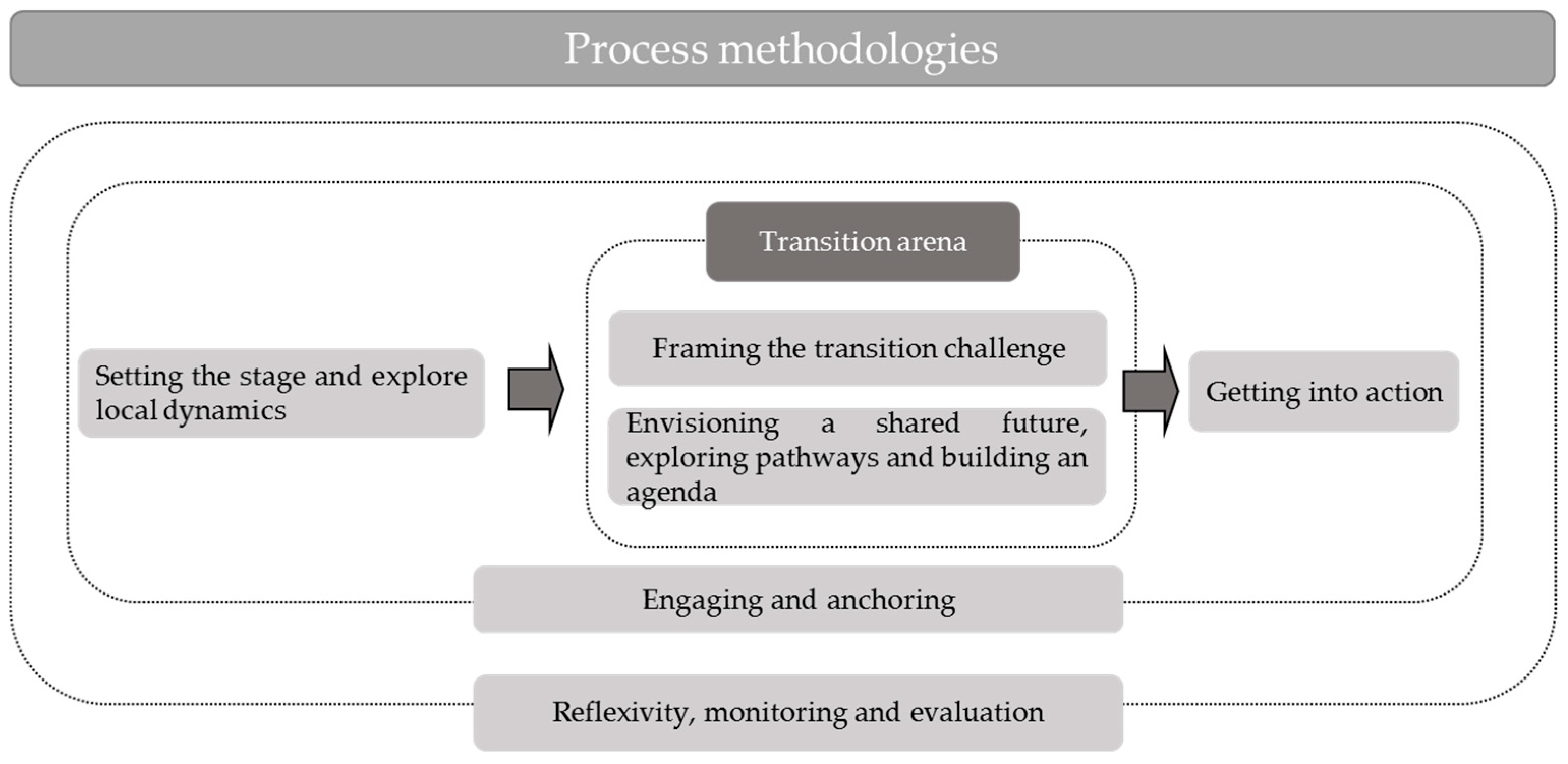

5. Recommendations for the Design of Transition Management Processes

5.1. Setting the Stage and Explore Local Dynamics

5.2. Framing the Transition Challenge

5.3. Envisioning a Shared Future, Exploring Pathways and Building an Agenda

5.4. Engaging and Anchoring

5.5. Getting into Action

5.6. Reflexivity, Monitoring, and Evaluation

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations. Report of the Secretary-General, Progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2017; Volume 66. [Google Scholar]

- Hutton, G.; Chase, C. The Knowledge Base for Achieving the Sustainable Development Goal Targets on Water Supply, Sanitation and Hygiene. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akpabio, E.M.; Takara, K. Understanding and confronting cultural complexities characterizing water, sanitation and hygiene in Sub-Saharan Africa. Water Int. 2014, 39, 921–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobbinah, B.P.; Erdiaw-Kwasie, M.O.; Amoateng, P. Africa’s urbanisation: Implications for sustainable development. Cities 2015, 47, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J-PAL. J-PAL Urban Services Review Paper; Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, P.; Hall, A.W. Effective Water Governance; Technical Committee Background Papers No. 7; Global Water Partnership (GWP): Stockholm, Sweden, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Brikke, F.; Bredero, M. Linking Technology Choice with Operation and Maintenance in the Context of Community Water Supply and Sanitation; World Health Organization and IRC Water and Sanitation Centre: Geneva, Switzerland, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Lockwood, H.; Smits, S. Supporting Rural Water Supply: Moving Towards a Service Delivery Approach; Practical Action Publishing: Rugby, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ademiluyi, I.A.; Odugbesan, J.A. Sustainability and impact of community water supply and sanitation programmes in Nigeria: An overview. Afr. J. Agric. Res. 2008, 3, 811–817. [Google Scholar]

- Tsinda, A.; Abbott, P.; Pedley, S.; Charles, K.; Adogo, J.; Okurut, K.; Chenoweth, J. Challenges to Achieving Sustainable Sanitation in Informal Settlements of Kigali, Rwanda. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2013, 10, 6939–6954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UNDP/UUNDP Water Governance Facility/UNICEF. WASH and Accountability: Explaining the Concept” Accountability for Sustainability Partnership: UNDP Water Governance Facility at SIWI and UNICEF; UNDP/UUNDP: Stockholm, Sweden; New York, NY, USA, 2015; Available online: http://www.watergovernance.org/ (accessed on 17 October 2017).

- RWSN Handpump Data 2009. In Selected Countries in Sub-Saharan Africa; Rural Water Supply Network (RWSN): St Gallen, Switzerland, 2009.

- Hisschemöller, M.; Hoppe, R. Coping with Intractable Controversies: The Case for Problem Structuring in Policy Design and Analysis. In Knowledge, Power, and Participation in Environmental Policy Analysis; Hisschemöller, M., Hoppe, R., Dunn, W.N., Ravetz, J.R., Eds.; Transaction Publishers: New Brunswick, NJ, USA; London, UK, 2001; pp. 47–72. [Google Scholar]

- Rotmans, J. Societal Innovation: Between Dream and Reality Lies Complexity; Rotterdam Erasmus Research Institute of Management: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Loorbach, D.; Frantzeskaki, N.; Avelino, F. Sustainability Transitions Research: Transforming Science and Practice for Societal Change. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2017, 42, 599–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frantzeskaki, N.; de Haan, J. Transitions: Two steps from theory to policy. Futures 2009, 41, 593–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loorbach, D. Transition management for sustainable development: A prescriptive, complexity-based governance framework. Governance 2010, 23, 161–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittmayer, J.; Loorbach, D. Governing Transitions in Cities: Fostering Alternative Ideas, Practices, and Social Relations through Transition Management. In Governance of Urban Sustainability Transitions, Theory and Practice of Urban Sustainability Transitions; Loorbach, D., Wittmayer, J.M., Shiroyama, H., Fujino, J., Mizuguchi, S.D., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2016; pp. 1–195. [Google Scholar]

- Frantzeskaki, N.; Hölscher, K.; Wittmayer, J.M.; Avelino, F.; Bach, M. Transition Management in and for Cities: Introducing a New Governance Approach to Address Urban Challenges. In Co-Creating Sustainable Urban Futures, Future City 11; Frantzeskaki, N., Hölscher, K., Bach, M., Avelino, F., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2018; pp. 1–425. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Brugge, R.; van Raak, R. Facing the adaptive management challenge: Insights from transition management. Ecol. Soc. 2007, 12, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frantzeskaki, N.; Ferguson, B.C.; Skinner, R.; Brown, R.R. Guidance Manual: Key Steps for Implementing a Strategic Planning Process for Transformative Change; Dutch Research Institute for Transitions, Erasmus University Rotterdam: Rotterdam, The Netherlands; Monash Water for Liveability, Monash University: Melbourne, Australia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Frantzeskaki, N.; Shiroyama, H. Sketching future research directions for transition management applications in cities. In Governance of Urban Sustainability Transitions. European and Asian Experiences; Loorbach, D., Wittmayer, J.M., Shiroyama, H., Fujino, J., Mizuguchi, S., Eds.; Springer: Tokyo, Japan; Heidelberg, Germany; New York, NY, USA; Dordrecht, The Netherlands; London, UK, 2016; pp. 183–189. [Google Scholar]

- Pant, L.P.; Adhikari, B.; Bhattarai, K.K. Adaptive transition for transformations to sustainability in developing countries. Environ. Sustain. 2015, 14, 206–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvestri, G.; Frantzeskaki, N. A transition management approach for local sustainability. A case study from La Botija protected area, San Marcos de Colon. In Co-Creating Sustainable Urban Futures: A Primer on Applying Transition Management in Cities; Frantzeskaki, N., Hölscher, K., Bach, M., Avelino, F., Eds.; Part of the Future City Book Series, FUCI; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2015; Volume 11, p. 425. [Google Scholar]

- Poustie, M.S.; Frantzeskaki, N.; Brown, R.R. A transition scenario for leapfrogging to a sustainable urban water future in Port Vila, Vanuatu. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2016, 105, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roche, R.; Bain, R.; Cumming, O. A long way to go–Estimates of combined water, sanitation and hygiene coverage for 25 sub-Saharan African countries. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0171783. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Children’s Fund. UNICEF Annual Results Report: Water, Sanitation and Hygiene. 2014. Available online: www.unicef.org/publicpartnerships/files/2014_Annual_Results_Report_WASH.pdf (accessed on 23 November 2017).

- Schmidt, W.-P. The elusive effect of water and sanitation on the global burden of disease. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2014, 19, 522–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolf, J.; Prüss-Ustün, A.; Cumming, O.; Bartram, J.; Bonjour, S.; Cairncross, S.; Clasen, T.; Colford, J.M., Jr.; Curtis, V.; De France, J.; et al. Assessing the impact of drinking-water and sanitation on diarrhoeal disease in low- and middle-income settings: A systematic review and meta-regression. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2014, 19, 928–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benova, L.; Cumming, O.; Campbell, O.M. Systematic review and meta-analysis: Association between water and sanitation environment and maternal mortality. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2014, 19, 368–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Songa, J.; Machine, M.; Rakuom, C. Maternal child health through water, sanitation and hygiene. Sky J. Med. Med. Sci. 2015, 3, 94–104. Available online: http://www.skyjournals.org/SJMMS (accessed on 8 September 2017).

- Strunz, E.C.; Addiss, D.G.; Stocks, M.E.; Ogden, S.; Utzinger, J.; Freeman, M.C. Water, sanitation, hygiene, and soil-transmitted helminth infection: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2014, 11, e1001620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freeman, M.C.; Garna, J.V.; Sclar, G.D.; Boisson, S.; Medlicott, K.; Alexander, K.T.; Penakalapati, G.; Anderson, D.; Mahtani, A.G.; Grimes, J.E.T.; et al. The impact of sanitation on infectious disease and nutritional status: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2017, 220, 928–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabie, T.; Curtis, V. Handwashing and risk of respiratory infections: A quantitative systematic review. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2006, 11, 258–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghana Statistical Service (GSS). Ghana Poverty Mapping Report; Government of Ghana: Accra, Ghana, 2015.

- Grönwall, J.; Oduro-Kwarteng, S. Groundwater as a strategic resource for improved resilience: A case study from peri-urban Accra. Environ. Earth Sci. 2018, 77, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uganda Bureau of Statistics. The National Population and Housing Census 2014—Area Specific Profile Series; Uganda Bureau of Statistics: Kampala, Uganda, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- UN-HABITAT. Situation Analysis of Informal Settlements in Kampala; UN-HABITAT: Nairobi, Kenya, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- LWF/DRT/ACT, Baseline Survey. Kampala Slum Settlements: Where Access to Safe Water and Sanitation is Still a Challenge; Fact Sheet 002; Kansanga: Kampala, Uganda, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Aponte Rivero, C.E. A Socio-Spatial Analysis of Access to Groundwater in Low-Income Communities in Arusha, Tanzania. Master’s Thesis, UNESCO-IHE, Institute for Water Education, Delft, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 1–110. [Google Scholar]

- Grin, J.; Rotmans, J.; Schot, J.; Geels, F.; Loorbach, D. Transitions to Sustainable Development—Part 1. New Directions in the Study of Long Term Transformative Change; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Voß, J.; Bornemann, B. The politics of reflexive governance: Challenges for designing adaptive management and transition management. Ecol. Soc. 2011, 16, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voß, J.; Bauknecht, D.; Kemp, R. Reflexive Governance for Sustainable Development; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Van Buuren, M.W.; Loorbach, D. Policy innovation in isolation? Conditions for policy renewal by transition arenas and pilot projects. Public Manag. Rev. 2009, 11, 375–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Bosch, S. Transition Experiments: Exploring Societal Changes towards Sustainability; Erasmus University Rotterdam: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Roorda, C.; Wittmayer, J.; Henneman, P.; van Steenbergen, F.; Frantzeskaki, N.; Loorbach, D. Transition Management in the Urban Context: Guidance Manual; DRIFT, Erasmus University Rotterdam: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Nevens, F.; Frantzeskaki, N.; Gorissen, L.; Loorbach, D. Urban Transition Labs: Co-creating transformative action for sustainable cities. J. Clean. Product. 2013, 50, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittmayer, J.M.; Schäpke, N.; van Steenbergen, F.; Omann, I. Making sense of sustainability transitions locally: How action research contributes to addressing societal challenges. Crit. Policy Stud. 2014, 8, 465–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittmayer, J.M.; Schäpke, N. Action, research and participation: Roles of researchers in sustainability transitions. Sustain. Sci. 2014, 9, 483–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loorbach, D.; Wittmayer, J.M.; Shiroyama, H.; Fujino, J.; Mizuguchi, S.D. (Eds.) Governance of Urban Sustainability Transitions, Theory and Practice of Urban Sustainability Transitions; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2016; pp. 1–195. [Google Scholar]

- Hölscher, K.; Wittmayer, J.M.; Avelino, F.; Giezen, M. Opening up the transition arena: An analysis of (dis)empowerment of civil society actors in transition management in cities. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2017, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frantzeskaki, N.; Hölscher, K.; Bach, M.; Avelino, F. (Eds.) Co-Creating Sustainable Urban Futures: A Primer on Applying Transition Management in Cities; Part of the Future City Book Series, FUCI; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Wittmayer, J.M.; Roorda, C.; van Steenbergen, F. Governing Urban Sustainability Transitions: Inspiring Examples; DRIFT: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Shove, E.; Walker, G. CAUTION! Transitions ahead: Politics, practice, and sustainable transition management. Environ. Plan. Econ. Space 2007, 39, 763–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendriks, C. Policy design without democracy? Making democratic sense of TM. Policy Sci. 2009, 42, 341–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meadowcroft, J. What about the politics? Sustainable development, transition management, and long term energy transitions. Policy Sci. 2009, 42, 323–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jhagroe, S.; Loorbach, D. See no evil, hear no evil: The democratic potential of transition management. Environ. Innov. Soc. Trans. 2014, 15, 65–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avelino, F.; Grin, J.; Jhagroe, S.; Pel, B. The Politics of Sustainability Transitions. Environ. Policy Plan. 2016, 18, 557–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nevens, F.; Roorda, C. A climate of change: A transition approach for climate neutrality in the city of Ghent (Belgium). Sustain. Cities Soc. 2014, 10, 112–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hölscher, K.; Wittmayer, J.M. A German experience: The challenges of mediating ‘ideal-type’ Transition Management in Ludwigsburg. In Co-Creating Sustainable Urban Futures. A Primer on Applying Transition Management in Cities; Frantzeskaki, N., Hölscher, K., Bach, M., Avelino, F., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 205–224. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, U.E.; Nygaard, I.; Romijn, H.; Wieczorek, A.; Kamp, L.M.; Klerkx, L. Sustainability transitions in developing countries: Stocktaking, new contributions and a research agenda. Environ. Sci. Policy. 2018, 84, 198–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kooy, M.; Bakker, K. Splintered networks: The colonial and contemporary waters of Jakarta. Geoforum 2008, 39, 1843–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFarlane, C.; Rutherford, J. Political Infrastructures: Governing and Experiencing the Fabric of the City. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2008, 32, 363–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranganathan, M. Paying for Pipes, Claiming Citizenship: Political Agency and Water Reforms at the Urban Periphery. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2014, 38, 590–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutherford, J.; Coutard, O. Urban Energy Transitions: Places, Processes and Politics of Socio-technical Change. Urban Stud. 2014, 51, 1353–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasala, S.E.; Burra, M.M.; Mwankenja, T.S. Access to Improved Sanitation in Informal Settlements: The Case of Dar es Salaam City, Tanzania. Curr. Urban Stud. 2016, 4, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organisation (WHO); The United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). Progress on Drinking Water, Sanitation and Hygiene: 2017 Update and SDG Baselines; Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; World Health Organization (WHO): Geneva, Switzerland; United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF): Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Galan, D.I.; Kim, S.; Graham, J.P. Exploring changes in open defecation prevalence in sub-Saharan Africa based on national level indices. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koster, M. Fear and intimacy: Citizenship in a Recife Slum, Brazil. Ethnos 2014, 79, 215–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldorff, P. ‘The law is not for the poor’: Land, law and eviction in Luanda. Singap. J. Trop. Geogr. 2016, 37, 363–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilhelm-Solomon, M. Decoding dispossession: Eviction and urban regeneration in Johannesburg’s dark buildings. Singap. J. Trop. Geogr. 2016, 37, 378–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koster, M.; Nuijten, M. Coproducing urban space: Rethinking the formal/informal dichotomy. Singap. J. Trop. Geogr. 2016, 37, 282–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieczorek, A. Sustainability transitions in developing countries: Major insights and their implications for research and policy. Environ. Sci. Policy 2018, 84, 204–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grönwall, J. Self-supply and accountability: To govern or not to govern groundwater for the (peri-)urban poor in Accra, Ghana. Environ. Earth Sci. 2016, 75, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, S. Come Together, Right Now, Over What? An Analysis of the Processes of Democratization and Participatory Governance of Water and Sanitation Services in Dodowa, Ghana. Master’s Thesis, LUCSUS, Lund University Centre for Sustainability Studies, Lund, Sweden, 2016; pp. 1–67. [Google Scholar]

- Holm, R.H.; Kamangira, A.; Tembo, M.; Kasulo, V.; Kandaya, H.; Gijs Van Enk, P.; Velzeboer, A. Sanitation service delivery in smaller urban areas (Mzuzu and Karonga, Malawi). Environ. Urban. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjöstedt, M. The impact of secure land tenure on water access levels in sub-Saharan Africa: The case of Botswana and Zambia. Habitat Int. 2011, 35, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruce, J.W.; Freudenberger, M.S. Institutional Opportunities and Constraints in African Land Tenure: Shifting from a ‘Replacement’ to an ‘Adaptation’ Paradigm; Land Tenure Center: Madison, Mimeo, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Farvacque, C.; McAuslan, P. Reforming Urban Land Policies and Institutions in Developing Countries; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Isaksson, A.-S. Unequal Property Rights: A Study of Land Right Inequalities in Rwanda. Oxf. Dev. Stud. 2015, 43, 60–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, A.M. Uganda’s new urban policy: Participation, poverty, and sustainability. In Proceedings of the Sustainable Futures: Architecture and Urbanism in the Global South, Kampala, Uganda, 27–30 June 2012. [Google Scholar]

- UN-Habitat. Informal Settlements; Habitat III, 22; UN-Habitat: Nairobi, Kenya, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Nastar, M.; Abbas, S.; Aponte Rivero, C.; Jenkins, S.; Kooy, M. The emancipatory promise of participatory water governance for the urban poor: Reflections on the transition management approach in the cities of Dodowa, Ghana and Arusha, Tanzania. Afr. Stud. 2018, 77, 504–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creighton, J. Part one: Overview of public participation. In The Public Participation Handbook: Making Better Decisions through Citizen Involvement; Jossey-Bass: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2005; pp. 7–10. [Google Scholar]

- Devas, N.; Grant, U. Local Government Decision-Making—Citizen Participation and Local Accountability: Some Evidence from Kenya and Uganda. Public Adm. Dev. 2003, 23, 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayan, D. Voices of the Poor: Can Anyone Hear Us; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammed, A.K. Ghana’s Policy Making: From Elitism and Exclusion to participation and inclusion? Int. Public Manag. Rev. 2015, 16, 43–66. [Google Scholar]

- Freire, P. Education for Critical Consciousness New York; Seabury Press: New York, NY, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Van Welie, M.; Romijn, H.A. NGOs fostering transitions towards sustainable urban sanitation in low-income countries: Insights from Transition Management and Development Studies. Environ. Sci. Policy 2018, 84, 250–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Mejía, M.; Franco-Garcia, M.-L.; Jauregui-Becker, J.M. Sustainability transitions in the developing world: Challenges of sociotechnical transformations unfolding in contexts of poverty. Environ. Sci. Policy 2018, 84, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, P. Education and Social Inequality in Sub-Saharan Africa. J. Mod. Afr. Stud. 1980, 18, 201–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amenga-Etego, R. Water Privatization in Ghana: Women’s Rights under Siege; Paper presented at the Africa water conference on the right to water, Ghana; Integrated Social Development Centre (ISODEC): Accra, Ghana, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Rutaremwa, G.; Bemanzi, J. Inequality in School Enrolment in Uganda among Children of Ages 6–17 Years: The Experience after Introduction of Universal Primary Education—UPE. Sci. J. Educ. 2013, 1, 43–50. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. World Development Report 2006: Equity and Development; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Mugendawala, H. Inequity in Educational Attainment in Uganda: Implications for Government Policy. IJGE Int. J. Glob. Educ. 2012, 1, 93–101. [Google Scholar]

- Laverack, G. An identification and interpretation pf the organisational aspects of community empowerment. Oxf. Univ. Press Community Dev. J. 2001, 36, 134–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, H. Four different approaches to community participation. Oxf. Univ. Press Community Dev. J. 2005, 40, 286–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations; Economic and Social Council; Social Commission. Concepts and Principles of Community Development and Recommendations on further Practical Measures to be taken by International Organisations. Ekistics 1957, 4, 92–96. [Google Scholar]

- Altschuld, J.W.; Kumar, D.D. Needs Assessment: An Overview; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Voorberg, W.H.; Bekkers, V.J.J.M.; Tummers, L.G. A Systematic Review of Co-Creation and Co-Production: Embarking on the social innovation journey. Public Manag. Rev. 2014, 17, 1333–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frantzeskaki, N.; Kabisch, N. Designing a knowledge co-production operating space for urban environmental governance—Lessons from Rotterdam, Netherlands and Berlin, Germany. Environ. Sci. Policy 2016, 62, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banana, E.; Chitekwe-Biti, B. Co-producing inclusive city-wide sanitation strategies: Lessons from Chinhoyi, Zimbabwe. Copyright International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED). Environ. Urban. 2015, 27, 35–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisung, E.; Elliott, S.J.; Abudho, B.; Schuster-Wallace, C.J.; Karanja, D.M. Dreaming of toilets: Using photovoice to explore knowledge, attitudes and practices around water–health linkages in rural Kenya. Health Place 2015, 31, 208–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berrang-Ford, L.; Dingle, K.; Ford, J.D.; Lee, C.; Lwasa, S.; Namanya, D.B.; Henderson, J.; Llanos, A.; Carcamo, C.; Edge, V. Vulnerability of indigenous health to climate change: A case study of Uganda’s Batwa Pygmies. Soc. Sci. Med. 2012, 75, 1067–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clammer, J. Art, Culture and International Development. Humanizing Social Transformation; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Epskamp, K. Theatre for Development. An Introduction to Context, Applications and Trainings; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2006; pp. 1–192. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison, J.F. Forum Theater in West Africa: An Alternative Medium of Information Exchange. Res. Afr. Lit. 1991, 22, 29–40. [Google Scholar]

- Kar, K.; Chambers, R. Handbook on Community-Led Total Sanitation; Plan UK: London, UK; Institute of Development Studies: Brighton, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Sah, S.; Negussie, A. Community led total sanitation (CLTS): Addressing the challenges of scale and sustainability in rural Africa. Desalination 2009, 248, 666–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, G. Participatory Development. The Companion to Development Studies; Hodder Education: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Greig, A.; Hulme, D.; Turner, M. Challenging Global Inequality. Development Theory and Practice in the 21st Century; Palgrave Macmilan: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Eade, D. Capacity-Building: An Approach to People-Centered Development; Oxfam (UK and Ireland), Oxfam House, John Smith Drive: Oxford, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Sastre Merino, S.; de los Ríos Carmenado, I. Capacity building in development projects. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 46, 960–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaskin, R.J. Building Community Capacity: A Definitional Framework and Case Studies from a Comprehensive Community Initiative. Urban Aff. Rev. 2001, 36, 291–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uphoff, N. Fitting projects to people. In Putting People First: Sociological Variables in Rural. Process Approaches to Development; Chernea, M., Ed.; Oxford University: Oxford, UK, 1985; p. 1357. [Google Scholar]

- Van Koppen, B.; Smits, S.; Moriarty, P.; Penning de Vries, F.; Mikhail, M.; Boelee, E. Climbing the Water Ladder: Multiple-Use Water Services for Poverty Reduction; TP Series No. 52; IRC International Water and Sanitation Centre and International Water Management Institute: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2009. [Google Scholar]

| Context Dimensions | Conceptual Challenges (Relating to the Principles) | Application Challenges (Relating to Governance Activities) |

|---|---|---|

| Multiplicity of WASH practices, structures and arrangements | Open up the understanding of the ‘regime’ as coherent entity by paying attention to formal and informal practices, structures and arrangement as well as to their multiplicity | Strategic: Take stock of informal and formal practices, structures and arrangements as well as their multiplicity in the system analysis Operational: -Design the process taking specific local challenges and needs as well as strengths into account. -Design and select context-sensitive transition experiments that combine the advantages of decentral and multiple practices with the need to making these more equal, sustainable and long-lasting. |

| Governance capacities for WASH services and maintenance | Consider the limitations of open and equal collaboration in a protected space, since this presupposes at least a certain degree of trust, mutual respect and social equality | Strategic: Take account of multiple knowledges in identifying current roles, responsibilities and (power) relations (system analysis) Tactical: Enhance trust building and political awareness among actors from different societal domains as part of the process Operational: Strengthen governance capacities to maintain and sustain transition experiments over time Reflexive: Build capacities, address uneven power relations and enhance collaboration through shared monitoring and evaluation of process and outcomes |

| Landownership for sustainable access to WASH | Reconsider the contours and duration of a protected space that enables nurturing of innovations in the face of existential insecurity and legal uncertainty | Strategic: Take account of landownership in systems analysis Strategic/tactical: Include solutions for landownership issues in visions and pathways Operational: Design and/or select transition experiments that address legal uncertainty as well as existential insecurity, and thereby enhance equal access to water |

| Public participation in decision-making related to WASH | Address the issue of limited space for deviant and alternative ideas, practices, and social relations | Strategic/operational: Design processes that use different forms of interaction and participation to engage various actors with clear expectation management Operational: Set up transition experiments related to capacity building, democratic consciousness and popular education Reflexive: Use a shared monitoring and evaluation of process and outcomes to identify needs related to democratic principles |

| Socio-economic inequalities governing access to WASH | Consider the limitations for creating protected spaces and rethink selective participation of capable individuals | Strategic: -Design open and inclusive processes by considering alternative ways to select and engage actors -Consider approaches that give a voice to the most vulnerable and less powerful actors and create a safe environment -Integrate capacity building and skills development in the transition management process Operational: Design experiments that address and alter social inequalities and poverty related to access to basic services Reflexive: Make ‘equal access’ a prominent indicator for the monitoring and evaluation activities |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Silvestri, G.; Wittmayer, J.M.; Schipper, K.; Kulabako, R.; Oduro-Kwarteng, S.; Nyenje, P.; Komakech, H.; Van Raak, R. Transition Management for Improving the Sustainability of WASH Services in Informal Settlements in Sub-Saharan Africa—An Exploration. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4052. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10114052

Silvestri G, Wittmayer JM, Schipper K, Kulabako R, Oduro-Kwarteng S, Nyenje P, Komakech H, Van Raak R. Transition Management for Improving the Sustainability of WASH Services in Informal Settlements in Sub-Saharan Africa—An Exploration. Sustainability. 2018; 10(11):4052. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10114052

Chicago/Turabian StyleSilvestri, Giorgia, Julia M. Wittmayer, Karlijn Schipper, Robinah Kulabako, Sampson Oduro-Kwarteng, Philip Nyenje, Hans Komakech, and Roel Van Raak. 2018. "Transition Management for Improving the Sustainability of WASH Services in Informal Settlements in Sub-Saharan Africa—An Exploration" Sustainability 10, no. 11: 4052. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10114052

APA StyleSilvestri, G., Wittmayer, J. M., Schipper, K., Kulabako, R., Oduro-Kwarteng, S., Nyenje, P., Komakech, H., & Van Raak, R. (2018). Transition Management for Improving the Sustainability of WASH Services in Informal Settlements in Sub-Saharan Africa—An Exploration. Sustainability, 10(11), 4052. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10114052