Semantic Network Analysis of Legacy News Media Perception in South Korea: The Case of PyeongChang 2018

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

Partisanship of South Korean Press and Framing

3. Theoretical Framework

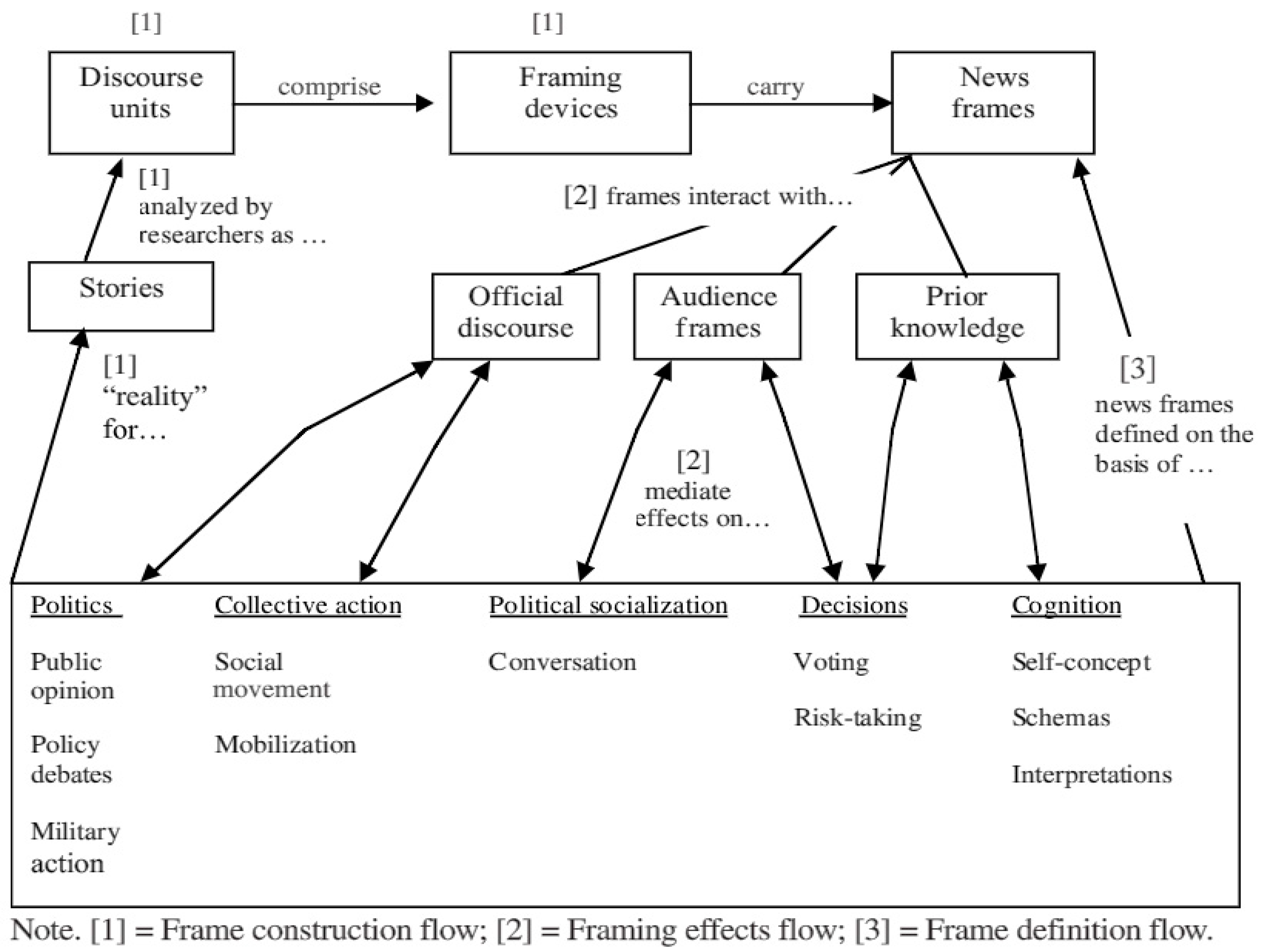

3.1. Framing

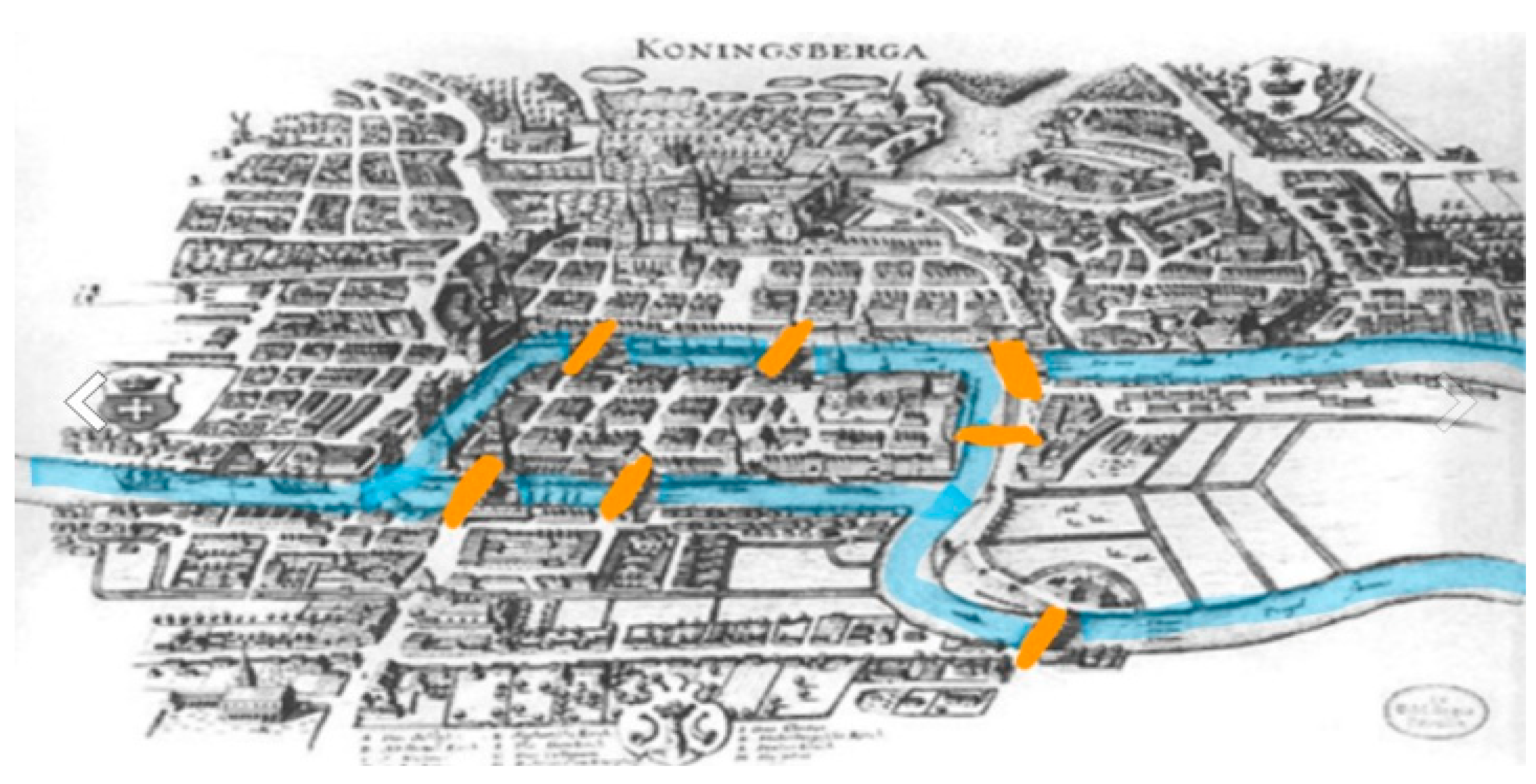

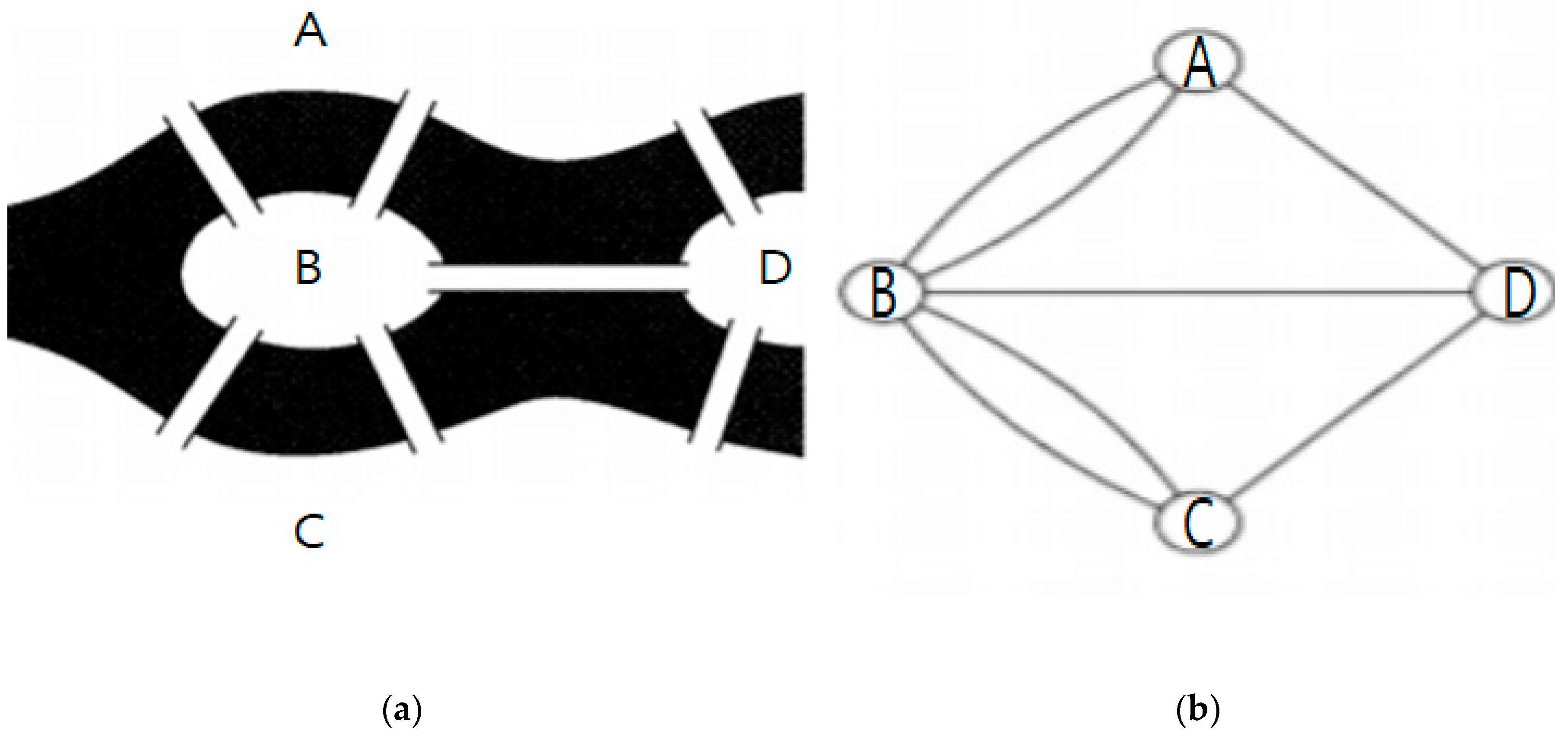

3.2. Graph Theory

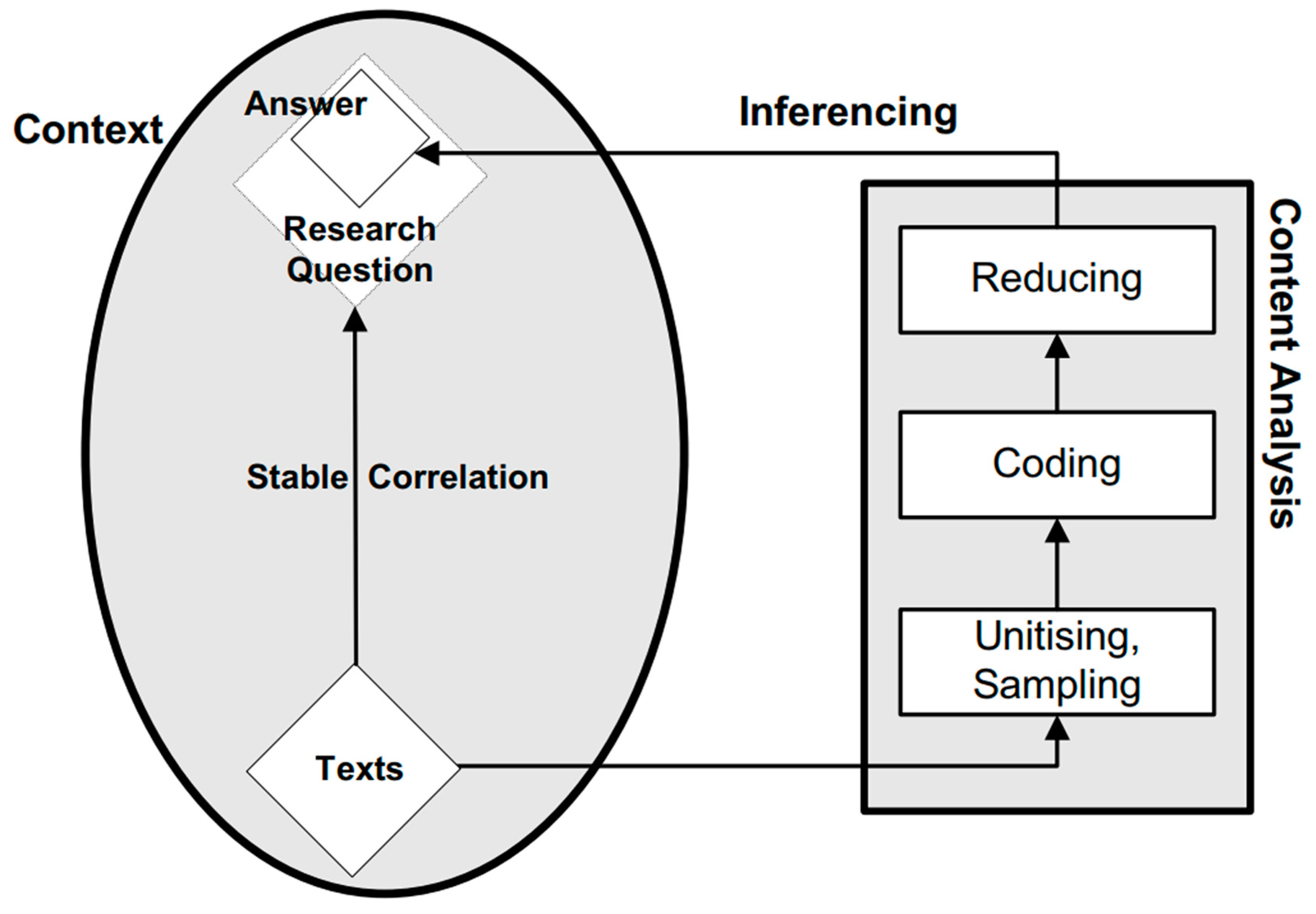

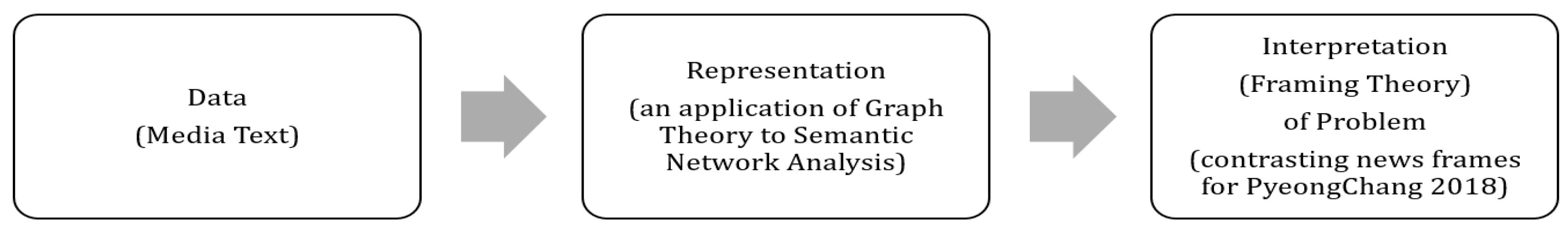

3.3. Algorithm of Theoretical Framework

4. Methods

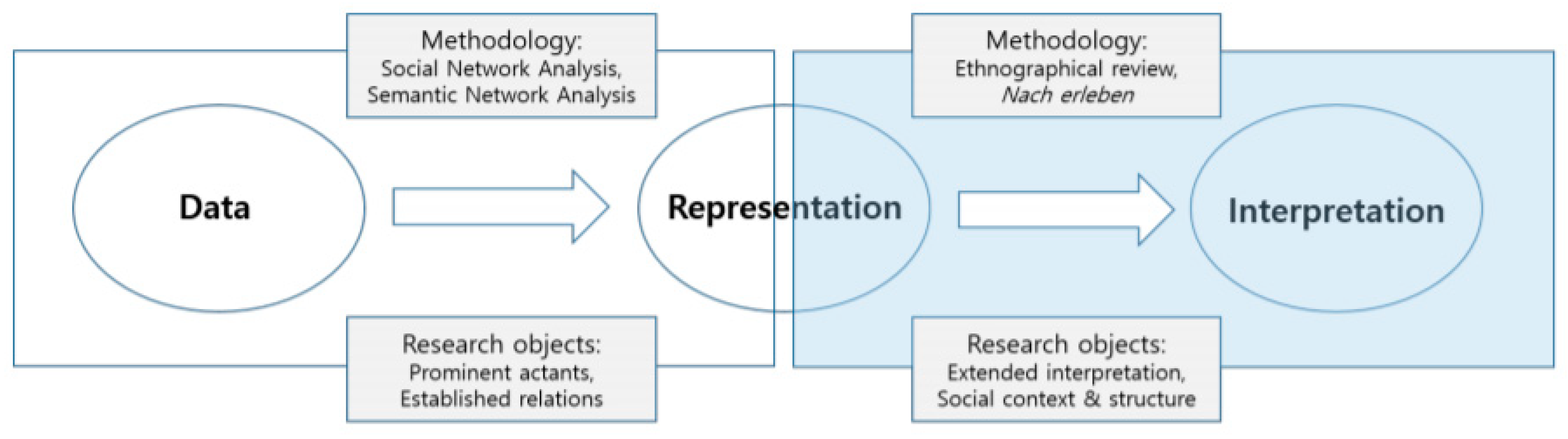

4.1. Semantic Network Analysis

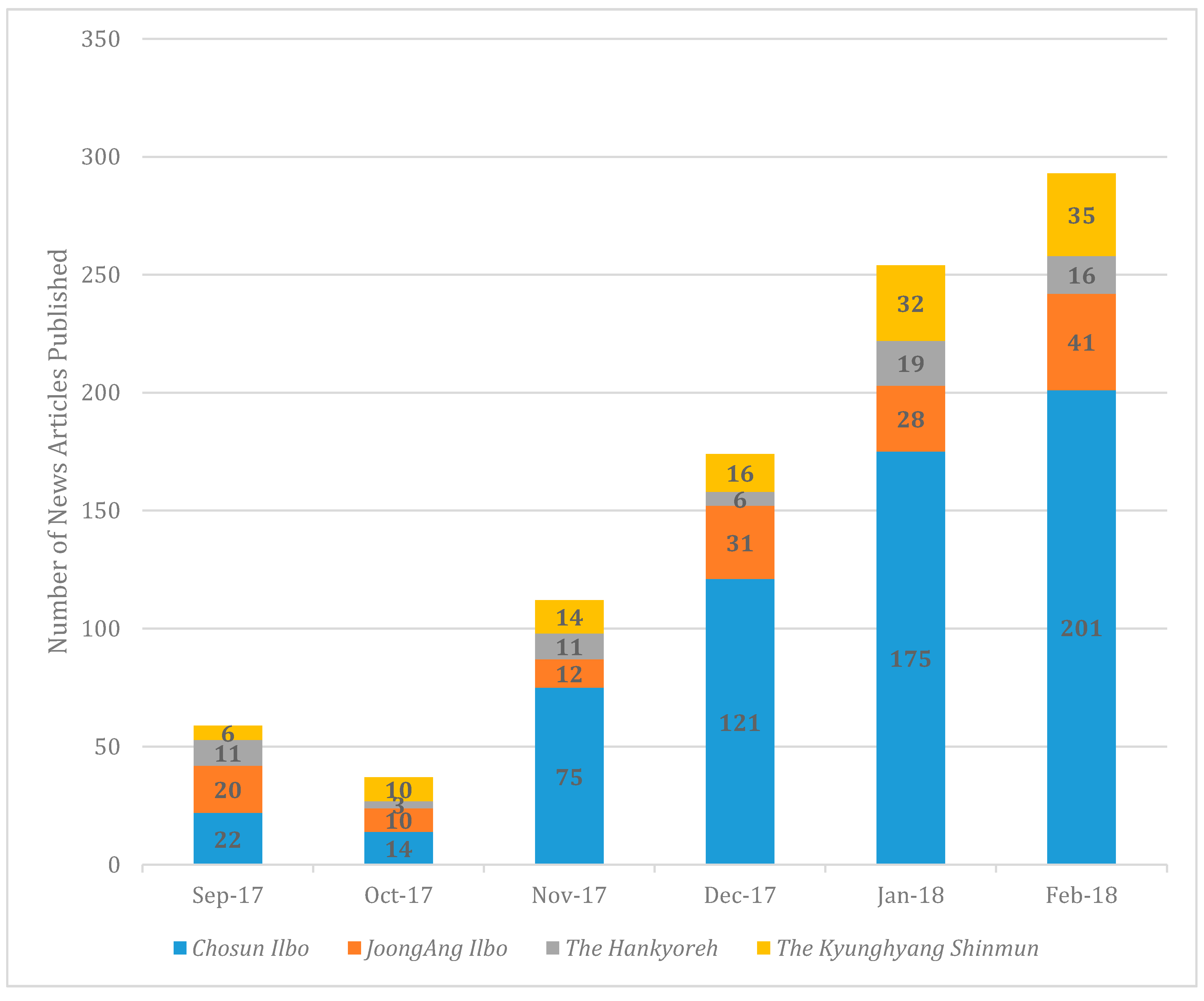

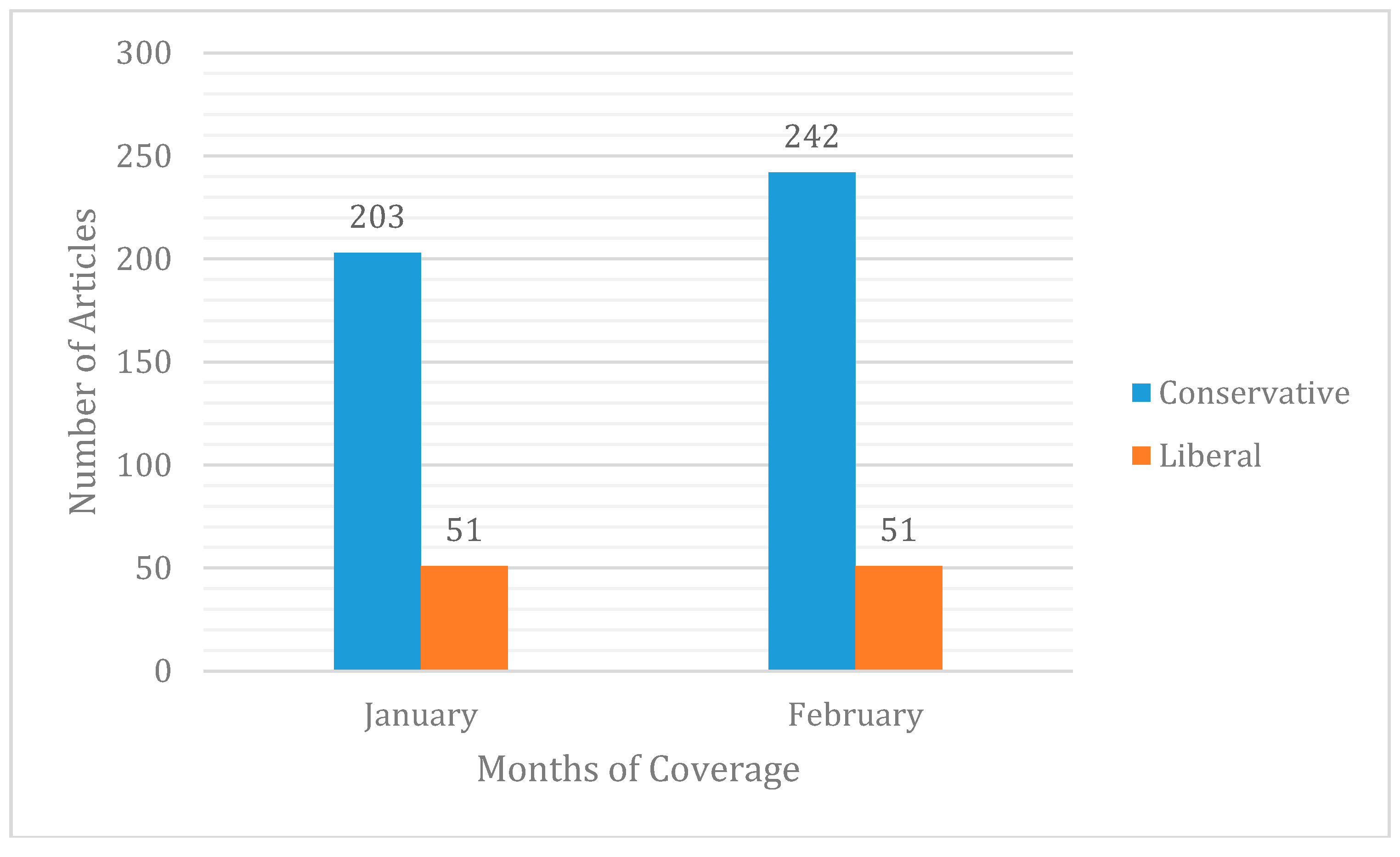

4.2. Data

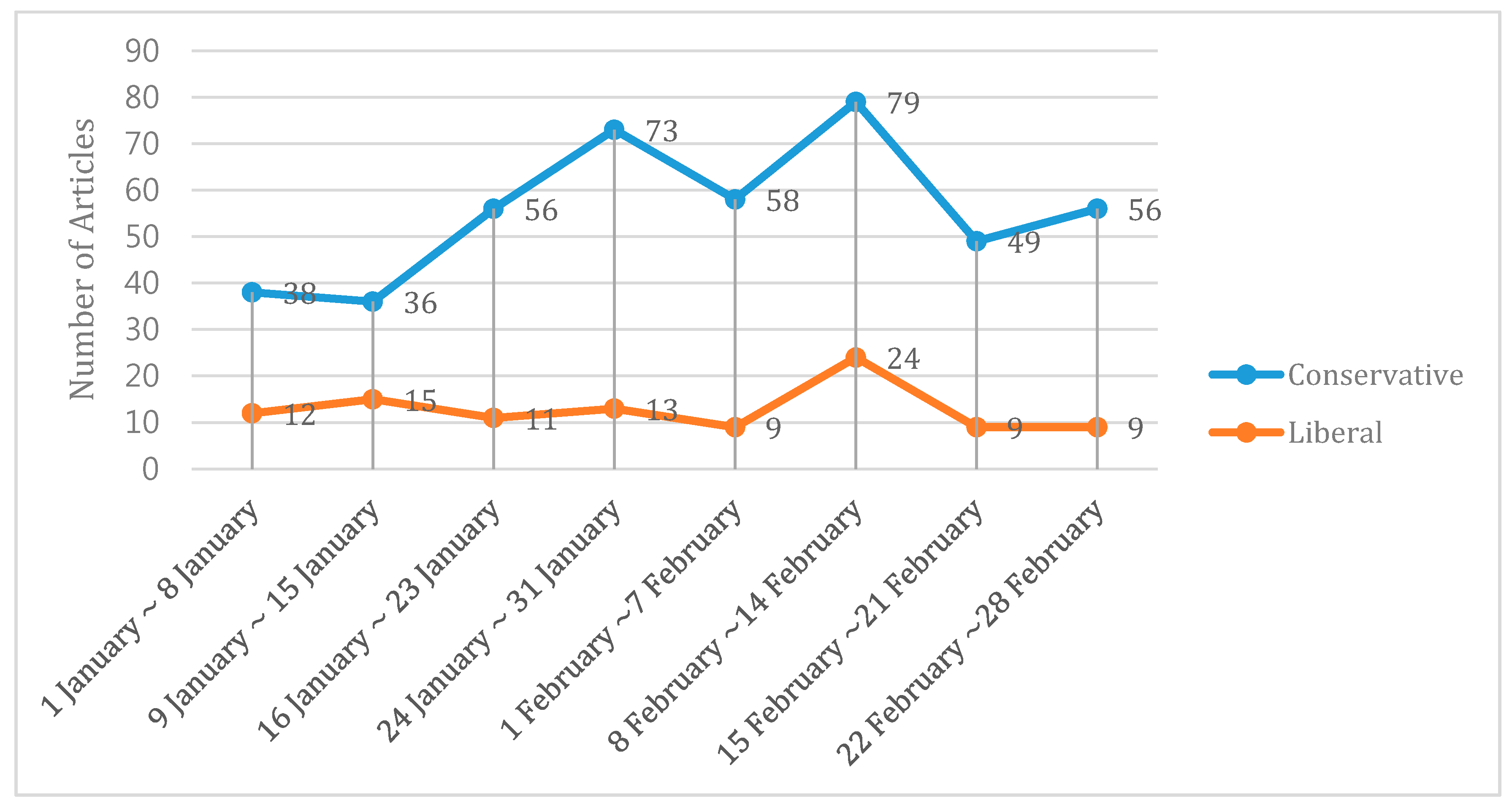

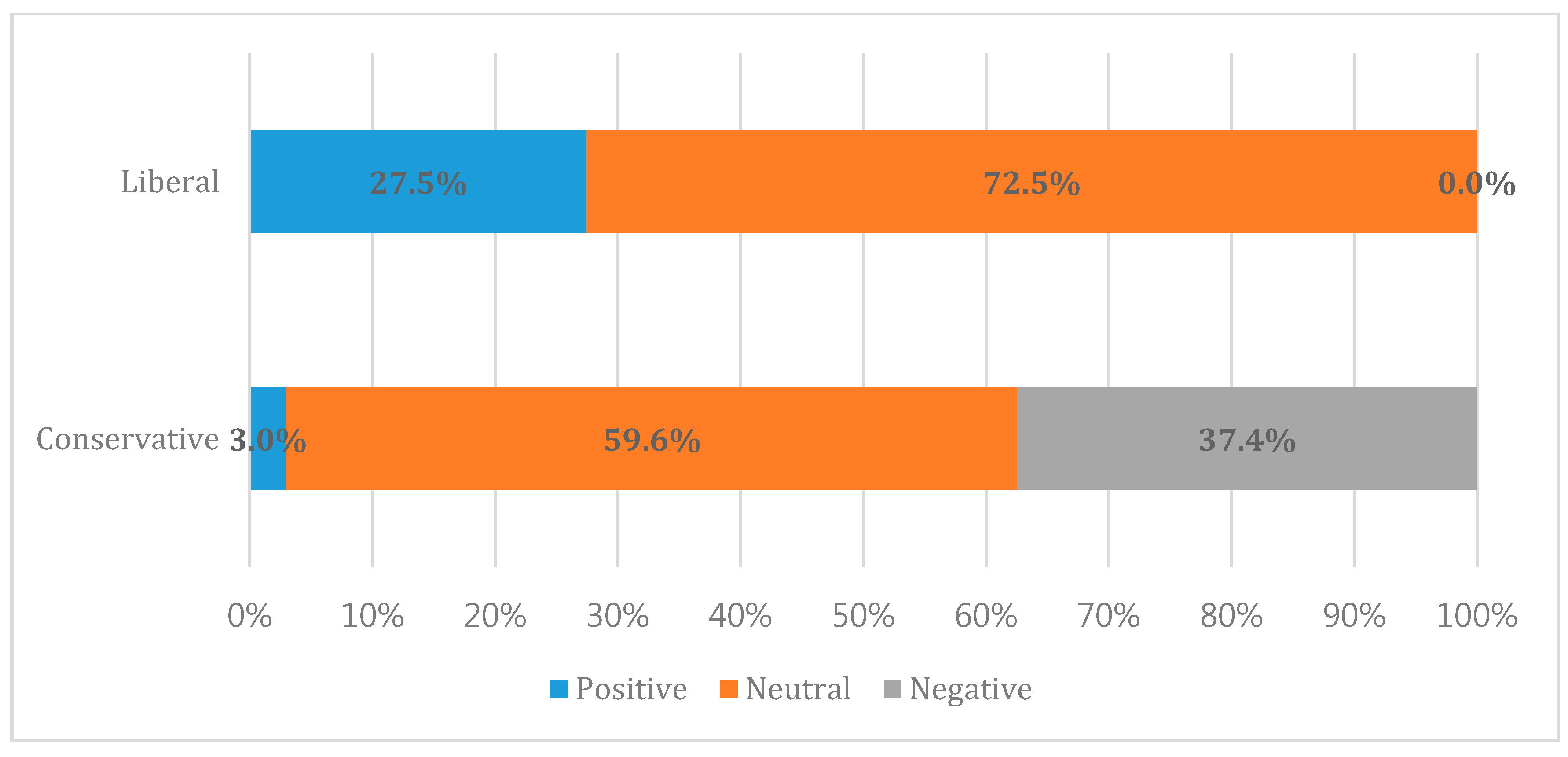

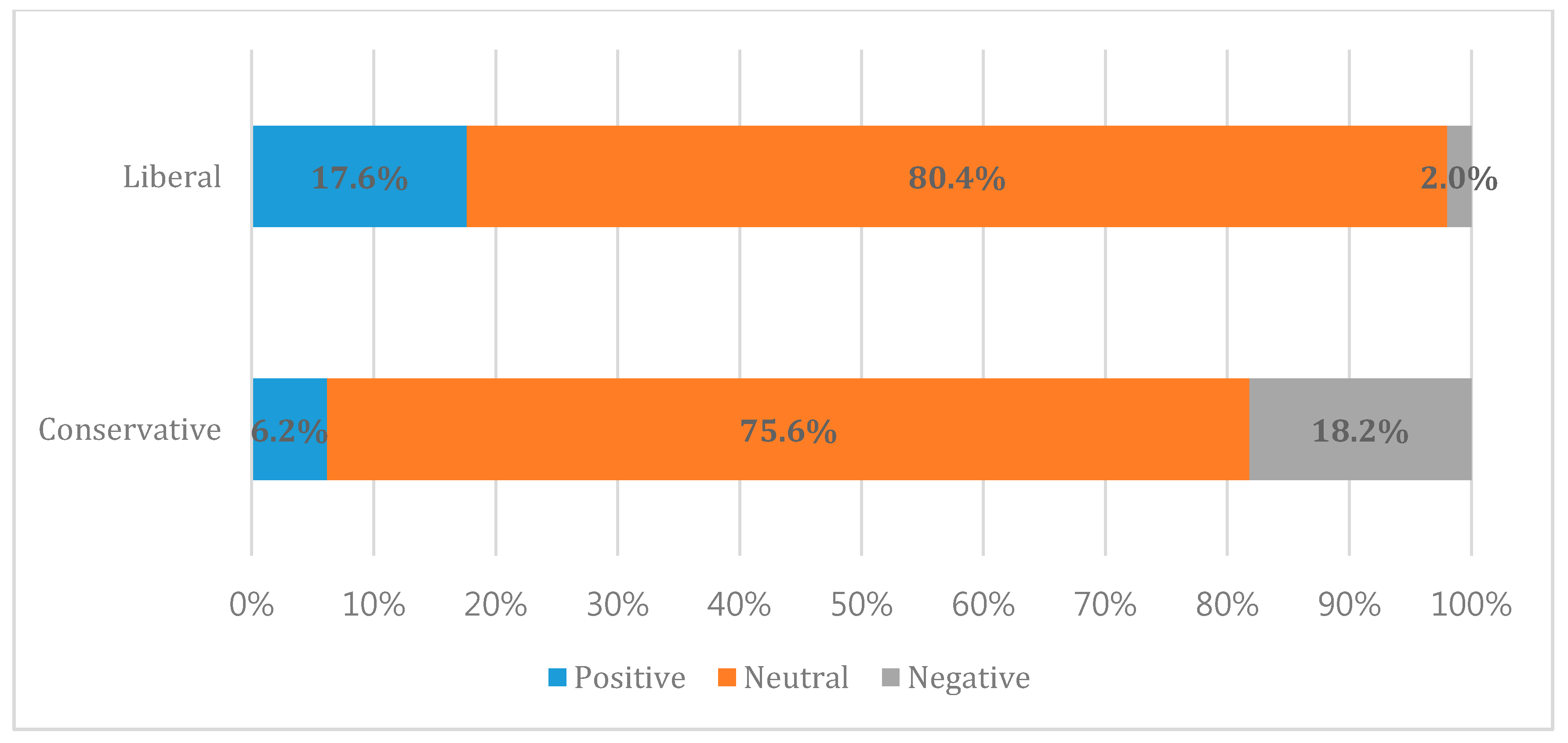

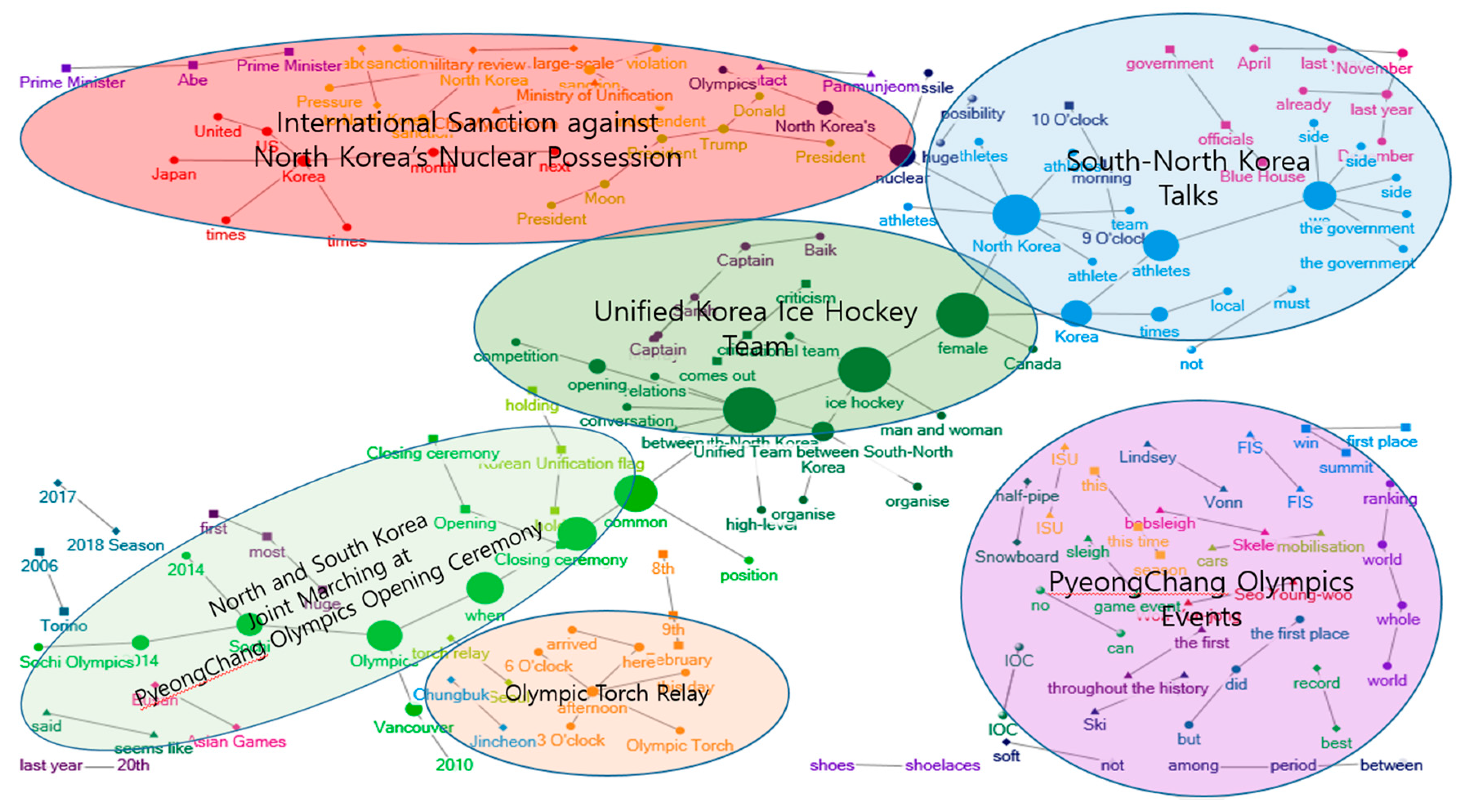

5. Results

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Van Attelveldt, W. Introduction. In Semantic Network Analysis: Techniques for Extracting, Representing and Querying Media Content; BookSurge Publishing: North Charleston, SC, USA, 2008; ISBN 1439211361. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.-T. A Study on the Strategy and SWOT Analysis of Hosting the 2018 Pyeongchang Winter Olympic Games. J. Korea Entertain. Ind. Assoc. 2011, 5, 14–24. (In Korean) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-D.; Ji, W.-S.; Lee, S.; Park, S.-Y. Inter-Regional Development Projects for the Co-prosperity of Gyeonggi-Do and Gangwon-Do on the 2018 PyeongChang Winter Olympic Game, Gyeonggi Research Institute, Policy Research Series 2011-66. Available online: http://www.gri.re.kr/%EC%97%B0%EA%B5%AC%EB%B3%B4%EA%B3%A0%EC%84%9C/?brno=3838&prno=3242 (accessed on 21 October 2018). (In Korean).

- Ryu, J.-H. 2018 PyeongChang Olympic Games and Regional Development Issues. Korea Tour. Policy. 2011, 45. Korea Culture & Tourism Institute. Available online: http://www.dbpia.co.kr/Journal/ArticleDetail/NODE01921445# (accessed on 21 October 2018). (In Korean).

- Ahn, D. A Contemplation for the Success of 2018 PyeongChang Olympics. Korea Tour. Policy 2011, 45. Available online: http://www.dbpia.co.kr/Journal/ArticleDetail/NODE01921444 (accessed on 21 October 2018). (In Korean).

- Cha, M. A Study on the Successful Hosting of the PyeongChang Winter Olympics through Regional Networking and Cooperation. Plan. Policy 2011, 362, 14–21. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Yeom, D. The Effect of Intention of the Local Residents for Cooperation for the 2018 Pyeongchang Winter Olympics on Regional Development and Sport Culture. J. Korean Soc. Wellness 2016, 11, 1–12. (In Korean) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, L.; Kim, N. Connecting Opinion, Belief and Value: Semantic Network Analysis of a UK Public Survey on Embryonic Stem Cell Research. J. Sci. Commun. 2015, 14. Available online: https://jcom.sissa.it/sites/default/files/documents/JCOM_1401_2015_A01.pdf (accessed on 19 October 2018).

- Kim, Y. Political Orientation of Korean Media and the Crisis in Social Communication. In Communication Crisis in the Korean Society; Korean Society for Journalism and Communication Studies, Ed.; Communication Books: Seoul, Korea, 2001; pp. 170–217. ISBN 9788964061862. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Kahn, K.; Kenney, P. The Slant of the News: How Editorial Endorsements Influence Campaign Coverage and Citizens’ Views of Candidates. Am. Political Sci. Rev. 2002, 96, 381–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoemaker, P.; Reese, S. Mediating the Messages: Theories of Influences on Mass Media Content, 2nd ed.; Longman Publication: New York, NY, USA, 1996; ISBN 0801312515. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, J. Political Economy of Communication: A Study on Structural Barrier of Communication. In Communication Crisis in the Korean Society; Korean Society for Journalism and Communication Studies, Ed.; Communication Books: Seoul, Korea, 2011; pp. 65–89. ISBN 9788964061862. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Kang, M. Media War and the Crisis of Journalism Practices. Korean J. Journal. Commun. Stud. 2004, 48, 319–421. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Nam, S. Media Crisis and Professional Journalists’ Responsibilities. Kwanhun J. 2009, 113, 89–109. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Patterson, T. Out of Order; Vintage Books: New York, NY, USA, 1994; ISBN 0679755101. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J. Editorial Tone of Major Korean Newspapers toward the Sunshine Policy during the Kim Dae Joong Government. Korean Political Sci. Rev. 2003, 37, 197–218. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Lee, W. Ideological Tendency and Assessment of the Government Policy through Reporting South-North Korea Issue: Comparative Analysis of Editorials under Kim Young-Sam and Kim Dae-Jung Administrations. Korean J. Commun. Inf. 2006, 35, 329–361. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Song, Y. A Study on the Korean Newspapers’ Objectifying Strategies. Korean J. Journal. Commun. Stud. 2007, 51, 229–251. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Choi, H. A Study on the Diversity of Korean Newspapers: Analyzing the Tendencies of Covering Three Major Issues. Korean J. Journal. Commun. Stud. 2010, 54, 399–426. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Kim, K.; Noh, G. A Comparative Study of News Reporting about North Korea on Newspapers in South Korea. Korean J. Journal. Commun. Stud. 2011, 55, 361–387. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Koh, Y. An Analysis of News Reports about the Scandals of the Presidents’ Relatives and In-laws’: A News Frame Approach. Commun. Theor. 2007, 3, 156–195. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.; Lim, Y. An Analysis of News Reports about Government-Media Relationships and Media Policies: Comparison of News Contents under Noh-Lee Governments. Korean J. Journal. Commun. Stud. 2009, 53, 94–115. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Kim, I. A Study on the News Frame Analysis of 2008 Candlelight Protesting: Focusing on the Ideological Polarization of Main Newspapers. Ph.D. Thesis, Kyung Hee University, Seoul, Korea, 2010. (In Korean). [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.; Kim, C.; Kim, H. Discursive Politics of the Media and Economic Crisis: A Case Study about ‘Korea’s September Crisis in 2008’. Korean J. Commun. Inf. 2010, 50, 164–185. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Park, D.; Cho, Y.; Hong, J. A Qualitative Study of News Source-Reporter Relations: On the Problems of Beat Reporting System. Korean J. Commun. Stud. 2001, 45, 367–397. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Hong, J.; Kim, K. The Influence of the Ideological Tendency of the Press on the Theme and the Tone of the Press Related with New Media Policy. J. Korea Contents Assoc. 2017, 17, 162–177. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Entman, R. Framing: Toward Clarification of a Fractured Paradigm. J. Commun. 1993, 43, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, V.; Tewksbury, D. News Values and Public Opinion: A Theoretical Account of Media Priming and Framing. In Progress in Communication Sciences; Barnett, G., Boster, F., Eds.; Ablex: New York, NY, USA, 1997; Volume 13, pp. 173–212. ISBN 9781566402770. [Google Scholar]

- Scheufele, D.; Tewksbury, D. Framing, Agenda Setting, and Priming: The Evolution of Three Media Effects Models. J. Commun. 2007, 57, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- d’Angelo, P. News Framing as a Multiparadigmatic Research Program: A Response to Entman. J. Commun. 2002, 52, 870–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Z.; Kosicki, G. Framing Analysis: An Approach to News Discourse. Political Commun. 2007, 10, 55–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fillmore, C.; Atkins, B. Toward a Frame-Based Lexicon: The Semantics of RISK and its Neighbors. In Frames, Fields and Contrasts: New Essays in Semantic and Lexical Organization; Lehrer, A., Kittay, E., Eds.; Lawrence Eribaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1992; pp. 75–102. ISBN 9780805810899. [Google Scholar]

- Nerlich, B.; Koteyko, N. Carbon Reduction Activism in the UK: Lexical Creativity and Lexical Framing in the Context of Climate Change. Environ. Commun. 2009, 3, 206–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degani, M. Values and Lexical Preferences in Obama’s Speeches. In Framing the Rhetoric of a Leader; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2015; pp. 202–224. ISBN 9781349501014. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, M.E.J.; Barabási, A.; Watts, D.J. The Structure and Dynamics of Networks; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2006; ISBN 9780691113579. [Google Scholar]

- Barabási, A. Chapter 2 Graph Theory. In Network Science; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2016; ISBN 9781107076266. [Google Scholar]

- Almgren, K.; Kim, M.; Lee, J. Extracting Knowledge from the Geometric Shape of Social Network Data Using Topological Data Analysis. Entropy 2017, 19, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Saussure, F. Course in General Linguistics; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011; ISBN 9780231157261. [Google Scholar]

- Sowa, J. Principles of Semantic Networks; Morgan Kaufmann: San Mateo, CA, USA, 1991; ISBN 1558600884. [Google Scholar]

- Helbig, H. Knowledge Representation and the Semantics of Natural Language; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2006; ISBN 9783540299660. [Google Scholar]

- Drieger, P. Semantic Network Analysis as a Method for Visual Text Analytics. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013, 79, 4–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carley, K.; Pamquist, M. Extracting, Representing, and Analyzing Mental Models. Soc. Forces 1992, 70, 601–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doerfel, M. What constitutes semantic network analysis? A comparison of research and methodologies. Connections 1998, 21, 16–26. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, H. A Methodology for Frame Analysis: From Discourse to Cognitive Schemata. In Social Movements and Culture; Johnston, H., Klandermans, B., Eds.; UCL Press: London, UK, 1995; pp. 217–246. ISBN 0816625743. [Google Scholar]

- Doerfel, M.; Barnett, G. A Semantic Network Analysis of the International Communication Association. Hum. Commun. Res. 1999, 25, 589–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, K.; Barnett, G.; Taylor, L. Dynamics of Culture Frames in International News Coverage: A Semantic Network Analysis. Int. J. Commun. 2016, 10, 3710–3736. [Google Scholar]

- Schultz, F.; Kleinnijenhuis, J.; Oegema, D.; Utz, S.; van Atteveldt, W. Strategic Framing in the BP Crisis: A Semantic Network Analysis of Associated Frames. Public Relat. Rev. 2012, 38, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motta, G.; Baden, C. Evolutionary Factor Analysis of the Dynamics of Frames: Introducing a Method for Analyzing High-dimensional Semantic Data with Time-changing Structure. Commun. Methods Meas. 2013, 7, 48–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, C.; Legara, E.F.T.; Atun, J.M.L.; Monterola, C.P. News Frames of the Population Issue in the Philippines. Int. J. Commun. 2014, 8, 1247–1267. [Google Scholar]

- Chosun Ilbo. Available online: www.chosun.com (accessed on 31 October 2018).

- JoongAng Ilbo. Available online: http://joongang.joins.com (accessed on 31 October 2018).

- The Hankyoreh. Available online: www.hani.co.kr (accessed on 31 October 2018).

- The Kyunghyang Shinmun. Available online: www.khan.co.kr (accessed on 31 October 2018).

- Modified from Korea Audit Bureau of Certification, The Number of Paid Circulation of Daily Newspapers in 2017. Available online: http://www.kabc.or.kr/about/notices/100000002623?param.page=¶m.category=¶m.keyword= (accessed on 26 September 2018). (In Korean).

- Chung, S. External Images of the EU: Comparative Analysis of EU Representations in Three Major South Korean Newspapers and Their Internet Editions. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Canterbury, Christchurch, New Zealand, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Chosun.com. Are Choi Ryong-hae’s Visit to PyeongChang and Supports to North Korean the Violation of Sanction against North Korea? 5 January. Available online: http://news.chosun.com/site/data/html_dir/2018/01/05/2018010500248.html (accessed on 27 August 2018).

- Chosun.com. Violation against the Sanction in Case of Supporting North Korean Team’s Stay, Ship or Airplanes to PyeongChang. 11 January. Available online: http://news.chosun.com/site/data/html_dir/2018/01/11/2018011100310.html (accessed on 27 August 2018).

- Chosun.com. [Opinion] Can North-South Talks Reach the Disestablishment of North Korean Nuclear Weapons after PyeongChang Olympics. Available online: http://news.chosun.com/site/data/html_dir/2018/01/09/2018010903080.html (accessed on 1 October 2018).

- Chosun.com. [Public Opinion] North-South Talks, We Should Welcome but should not be Moved. Available online: http://news.chosun.com/site/data/html_dir/2018/01/09/2018010903111.html (accessed on 1 October 2018).

- Chosun.com. [Opinion] If there is no Taegukgi at the Opening Ceremony of PyeongChang Olympics. Available online: http://news.chosun.com/site/data/html_dir/2018/01/04/2018010403144.html (accessed on 27 August 2018).

- Hani.co.kr. Around North Korea’s New Year’s Address, The Minjoo Party of Korea and People’s Party “Welcomed” but the Liberty Korean Party Perceived it as “Mockery”. Available online: http://www.hani.co.kr/arti/PRINT/825903.html (accessed on 1 October 2018).

- Hani.co.kr. Joint March with Holding Korean Unification Flag…North and South open PyeongChang of Peace. Available online: http://www.hani.co.kr/arti/PRINT/827025.html (accessed on 1 October 2018).

- Khan.co.kr. [Opinion] Trump, Utilise North-South Talks as an Entrance to North-US Talks. Available online: http://news.khan.co.kr/kh_news/khan_art_view.html?art_id=201801052117005 (accessed on 1 October 2018).

- Hani.co.kr. Ri Son-gwon Began His Talk with Saying “the Present to Our People,” Cho Myoung-gyon Responded with Saying “Well Begun is Half Done”. Available online: http://www.hani.co.kr/arti/PRINT/827042.html (accessed on 1 October 2018).

- Khan.co.kr. The Synergy Coming Out of North Korea’s Participation in PyeongChang Olympics. Available online: http://sports.khan.co.kr/olympic/2018/pg_view.html?art_id=201801011837003&sec_id=530601 (accessed on 1 October 2018).

- Hani.co.kr. Special Law on Supporting Unified Korean Team of PyeongChang Olympics, which was Supported by the Liberty Korean Party during MB Administration. Available online: http://www.hani.co.kr/arti/politics/assembly/828755.html (accessed on 1 October 2018).

- Korea Gallup. Gallup Report. Available online: http://www.gallup.co.kr/gallupdb/report.asp?pagePos=4&selectyear=&search=&searchKeyword= (accessed on 12 September 2018).

- Bang, J. The roles of News Reports for recovering the homogeneity after the unification. In Korean Society for Journalism & Communication Studies; Symposium & Seminar: Seoul, Korea, 1995; pp. 17–49. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Choi, J.; Ha, J. News Frames of Korean Unification Issues: Comparing Conservative and Progressive Newspapers. Korean J. Commun. Stud. 2016, 24, 121–145. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Castell, M. The Rise of Network Society; Blackwell Publishers: Oxford, UK, 2000; ISBN 0631221409. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, H. Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide; New York University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006; ISBN 9780814742815. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, J. Candlelight and Media: The Mode of Convergence Media and the Emergence of Individualized Mass. Korean J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2011, 35, 97–122. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Song, T. The Multitude’s Foreign Policy Debates and its Collective Behaviour through Social Media: The Impact of Changing Communication Environment on the Public’s Foreign Policy Attitudes. Korean J. Int. Stud. 2013, 53, 41–87. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Hardt, M.; Negri, A. Empire; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2000; ISBN 0674006712. [Google Scholar]

- Hardt, M.; Negri, A. Multitude: War and Democracy in the Age of Empire; Penguin Press: New York, NY, USA, 2004; ISBN 1594200246. [Google Scholar]

- Wellman, B. Physical Place and Cyberspace: The Rise of Personalized Network. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2001, 25, 227–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morley, D. Media, Modernity, Technology: The Geography of the New; Routledge: London, UK, 2007; ISBN 0415333423. [Google Scholar]

- Levy, P. Collective Intelligence: Mankind’s Emerging World in Cyberspace; Plenum Trade: New York, NY, USA, 1997; ISBN 0738202614. [Google Scholar]

| Research Question 1 (Q1) | How have the conservative and the liberal newspapers shown their attitudes to PyeongChang 2018 in their news framings? Optimistically or pessimistically? |

| Research Question 2 (Q2) | Which type of newspapers was successful in influencing public opinion about PyeongChang 2018? Conservative or liberal? |

| Research Question 3 (Q3) | How did the South Korean public perceive PyeongChang 2018? Positively or negatively? |

| Research Question 4 (Q4) | Why did the South Korean public buy more of a particular type of newspapers (conservative or liberal)? |

| Media-Government Relationship | Political Orientations of the Regime | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Conservative | Liberal | ||

| Media | Conservative | I. Compatible | II. Incompatible |

| Liberal | III. Incompatible | IV. Compatible | |

| Political Orientation | Newspapers | Number of Articles |

|---|---|---|

| Conservative | Chosun Ilbo | 376 |

| JoongAng Ilbo | 69 | |

| Liberal | The Hankyoreh | 35 |

| The Kyunghyang Shinmun | 67 |

| Ranking | Newspaper Names | Paid Circulation | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Chosun Ilbo | 1,254,297 | Nationwide Daily Newspaper |

| 2 | DongA Ilbo | 729,414 | Nationwide Daily Newspaper |

| 3 | JoongAng Ilbo | 719,931 | Nationwide Daily Newspaper |

| 4 | The Maeil Business Newspaper | 550,536 | Economic Newspaper |

| 5 | The Korea Economic Daily | 352,999 | Economic Newspaper |

| 6 | The Nongmin Shinmun (published three times a week) | 287,884 | Newspaper for Farmers |

| 7 | The Hankyoreh | 202,484 | Nationwide Daily Newspaper |

| 8 | The Kyunghyang Shinmun | 165,133 | Nationwide Daily Newspaper |

| 9 | Munhwa Ilbo | 163,090 | Nationwide Daily Newspaper |

| 10 | The Hankook Ilbo | 159,859 | Nationwide Daily Newspaper |

| Conservative | Liberal | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Top Vertices | Betweenness Centrality | Top Vertices | Betweenness Centrality |

| North and South Korea | 556 | (South Korean) President | 27 |

| Ice Hockey | 549 | Olympics | 25 |

| Female | 539 | Moon Jae-in | 21 |

| North Korea | 445 | Trump | 15 |

| Unification | 359 | North and South Korea | 13 |

| Entrance | 296 | (North Korean) Workers’ Party | 12 |

| Moment | 266 | Kim Jong-un | 12 |

| Athletes | 249 | Chairman | 11 |

| Competition | 242 | North Korea | 10 |

| We | 210 | Peace | 7 |

| Korea | 177 | Participation | 7 |

| Nuclear | 128 | North Korea’s | 7 |

| Sochi | 128 | Nuclear | 6 |

| Unified Team | 87 | Unified Team | 5 |

| Held | 44 | High-level Talks | 5 |

| Vancouver | 44 | South Korea | 2 |

| 2014 | 44 | The US | 2 |

| North Korea | 44 | Tension | 1 |

| Perspective | 44 | (South Korean) Representatives | 1 |

| One | 19 | (South Korean) Ministry of Unification | 1 |

| Conservative | Liberal | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Top Vertices | Betweenness Centrality | Top Vertices | Betweenness Centrality |

| Korea | 8888.6829 | Held | 29 |

| Olympic Games | 6428.7636 | Saimdang Hall | 25 |

| Female | 4203.9763 | Gangneung Art Centre | 24 |

| Athletes | 4074.0719 | Gangwon Province | 21 |

| Of athletes | 3749.5833 | Female | 17 |

| During the training | 3380 | Afternoon | 16 |

| Female curling | 3374.2258 | Ice Hockey | 10 |

| Held | 3351.7491 | 8th of February | 9 |

| South Korea’s | 3230 | At Ice Arena | 9 |

| Claim | 3165 | An Eccentric Main | 6 |

| The first | 2994 | Former | 6 |

| At the competition | 2118.7878 | Pence (US Vice President) | 6 |

| Gangneung | 2007.9263 | North and South Korea | 6 |

| Players | 1966.9673 | Single Skating | 6 |

| Fujisawa | 1628 | Old man | 6 |

| Competitions | 1620 | Grump | 4 |

| Male | 1616.4879 | Whole | 4 |

| Match | 1561.5119 | Winter Olympics | 2 |

| Completed | 1448 | Short Track | 2 |

| South Korean National Team | 1438.7903 | Past | 1 |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yoon, S.-W.; Chung, S.W. Semantic Network Analysis of Legacy News Media Perception in South Korea: The Case of PyeongChang 2018. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4027. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10114027

Yoon S-W, Chung SW. Semantic Network Analysis of Legacy News Media Perception in South Korea: The Case of PyeongChang 2018. Sustainability. 2018; 10(11):4027. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10114027

Chicago/Turabian StyleYoon, Sung-Won, and Sae Won Chung. 2018. "Semantic Network Analysis of Legacy News Media Perception in South Korea: The Case of PyeongChang 2018" Sustainability 10, no. 11: 4027. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10114027

APA StyleYoon, S.-W., & Chung, S. W. (2018). Semantic Network Analysis of Legacy News Media Perception in South Korea: The Case of PyeongChang 2018. Sustainability, 10(11), 4027. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10114027