The Unexplored Contribution of Responsible Innovation in Health to Sustainable Development Goals

Abstract

1. Introduction

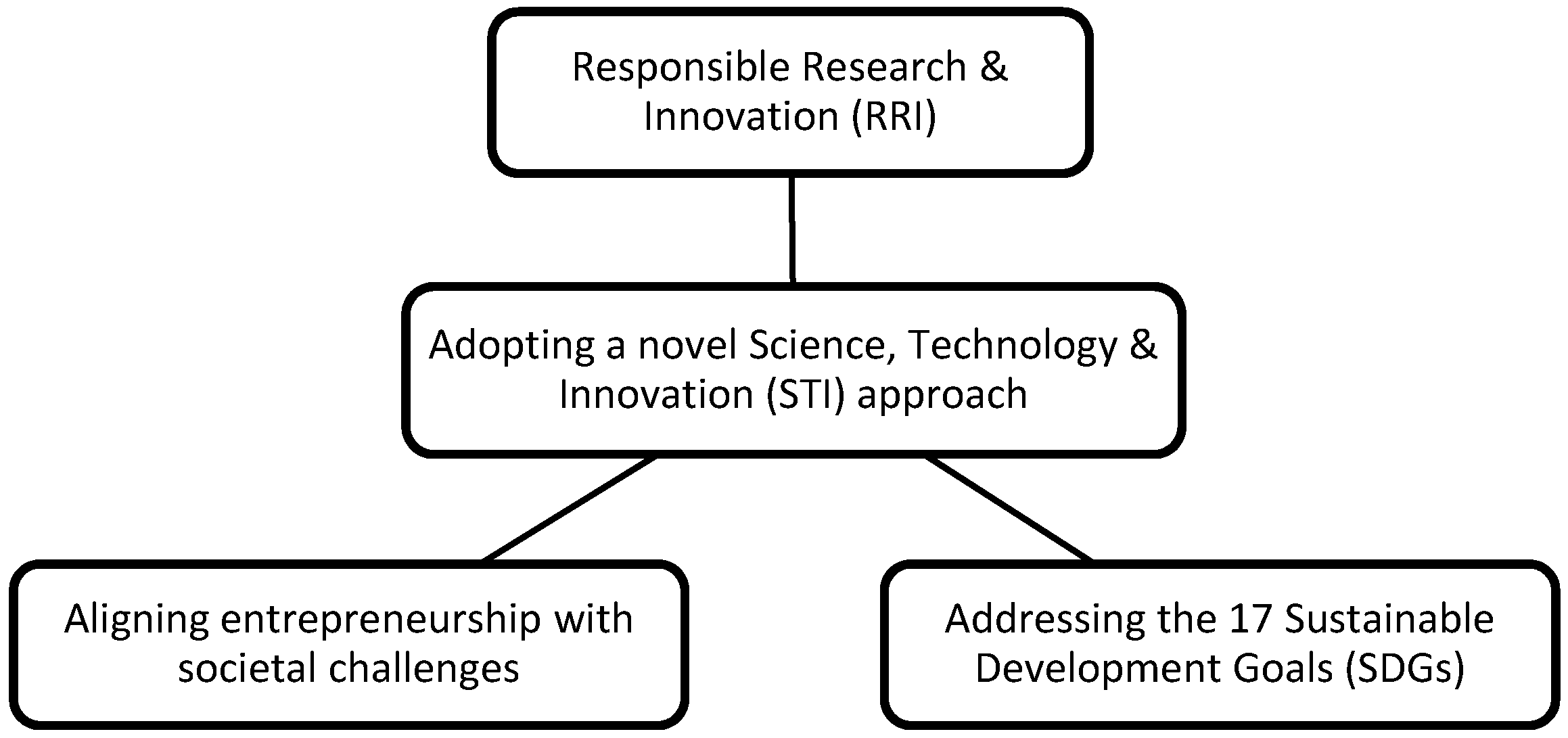

a collaborative endeavor wherein stakeholders are committed to clarify and meet a set of ethical, economic, social and environmental principles, values and requirements when they design, finance, produce, distribute, use and discard sociotechnical solutions to address the needs and challenges of health systems in a sustainable way.[9]

The STI Approach of Responsible Innovation in Health (RIH)

Commercially-driven innovation processes differ from those in research due to the priority given to achieving economic impact. Furthermore, the interests and values of innovators in the business context may differ from others (e.g., researchers in academia) and Research and Development departments face different constraints regarding confidentiality and public image.[16]

2. Approach and Methods

2.1. Inductive STI Policy Research Approach

2.2. Web-Based Horizon Scanning

2.3. Data Analyses

3. The Relationships RIH Entertains with the SDGs

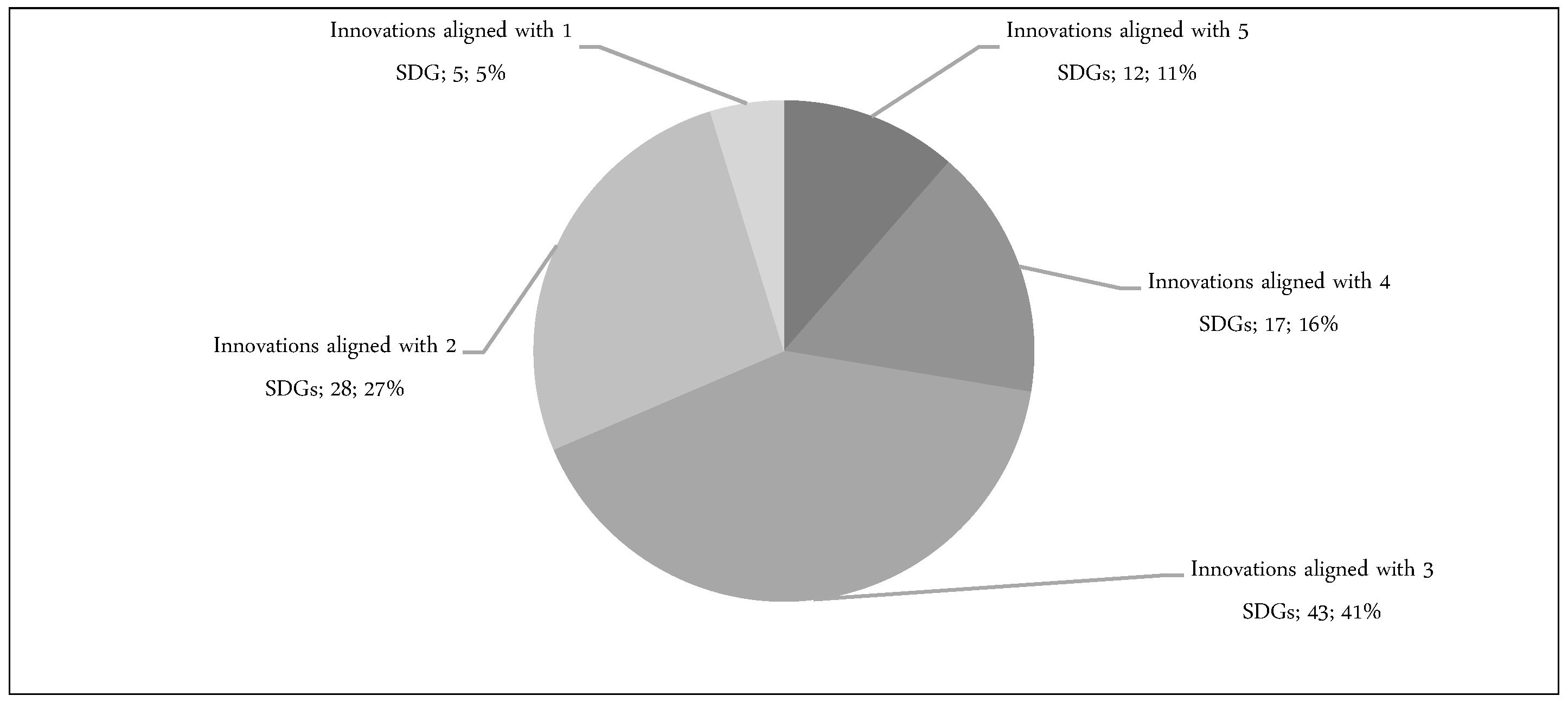

3.1. An Overview of Health Innovations with Responsibility Features

3.2. Three Examples

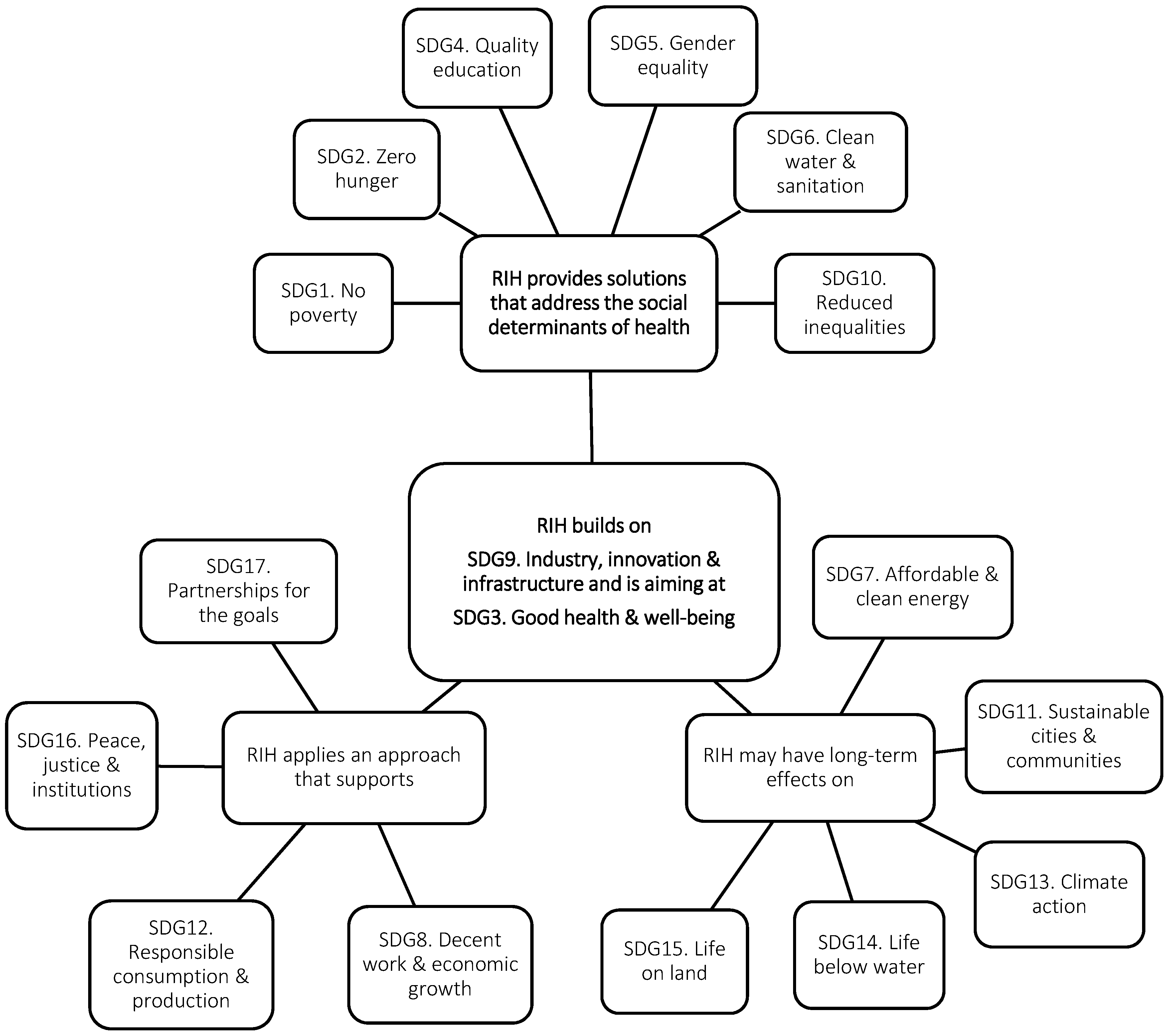

3.3. A Preliminary Framework of the Potential Relationships between RIH and the SDGs

4. Key Knowledge Gaps and Areas for Further Reflections

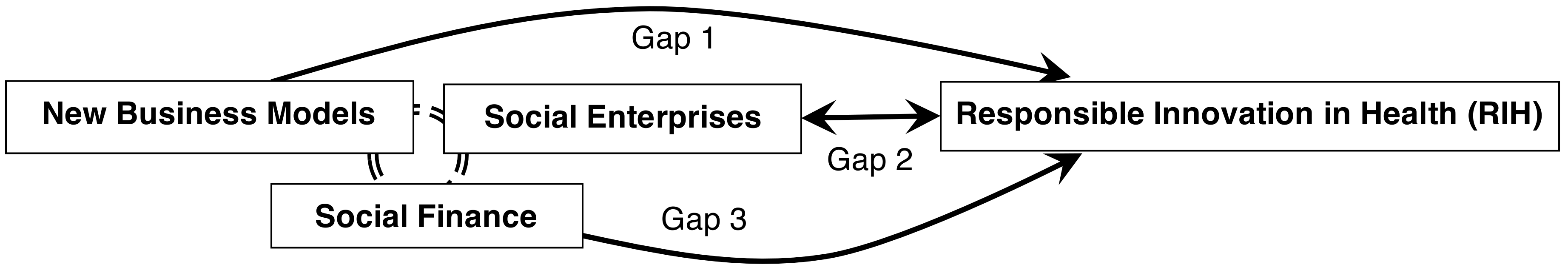

4.1. Knowledge Gaps

Social entrepreneurship and social innovation are anything but value-free, and have politically significant judgments of what the world should look like, and the role that innovation plays in this. Following from responsible innovation, one would suggest that in these alternative approaches to innovation, stakeholders should also be able to negotiate the terms of their inclusion and deliberation, including the politics behind these novel systems, and the substantive biases that can exist.[16]

- Gap 1: Identifying what alternative business models fit with sustainable and equitable health systems and what makes such business models better adapted to RIH;

- Gap 2: Identifying the organizational capacity needed by social enterprises to design and commercialize RIH, the risks these enterprises face and how the blended value (i.e., social and economic) they generate responds to health system-level challenges;

- Gap 3: Clarifying under what conditions social finance provides technology-based ventures with the resources and conditions they need to design and commercialize RIH, what metrics may be used to appraise their social and economic returns and what milestones are appropriate to track their progress.

4.1.1. Alternative Business Models and RIH

4.1.2. The Design and Commercialization of RIH through Social Entrepreneurship

4.1.3. The Unlocking of RIH by Social Finance

4.2. Areas for Further Reflections

4.2.1. The Need for Innovation within Innovation

4.2.2. Responsibility in the Practice of (Social) Entrepreneurs

Targets on sustainable production and resource efficiency that directly address businesses will not only support front runners in developing sustainable business models but will also put pressure on laggards to change unsustainable corporate practices.[71]

4.3. Strenghts and Limitations of This Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UNESCO. Multi-stakeholder forum on science, technology and innovation for the sustainable development goals: Summary by the co-chairs. In High-Level Political Forum on Sustainable Development, Convened under the Auspices of the Economic and Social Council, 11–20 July 2016; United Nations Economic and Social Council: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Science, Technology and Innovation for Sustainable Development, Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific Bangkok, 15–19 May 2016; United Nations Economic and Social Council: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. New Health Technologies: Managing Access, Value and Sustainability; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Medical Devices: Managing the Mismatch: An Outcome of the Priority Medical Devices Project; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hurst, J. Challenges for health systems in member countries of the organisation for economic co-operation and development. Bull. World Health Organ. 2000, 78, 751–760. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Halfon, N.; Conway, P.H. The opportunities and challenges of a lifelong health system. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 368, 1569–1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fong, H.; Harris, E. Technology, innovation and health equity. Bull. World Health Organ. 2015, 93, 438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demers-Payette, O.; Lehoux, P.; Daudelin, G. Responsible Research and Innovation: A productive model for the future of medical innovation. J. Responsib. Innov. 2016, 3, 188–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva Pacifico, H.; Lehoux, P.; Miller, F.A.; Denis, J.-L. Introducing Responsible Innovation in Health: A policy-oriented framework. Health Res. Policy Syst. 2018, 16, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lubberink, R.; Blok, V.; van Ophem, J.; Omta, O. A framework for Responsible Innovation in the business context: Lessons from responsible-, social-and sustainable innovation. In Responsible Innovation 3; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 181–207. [Google Scholar]

- Klaassen, P.; Kupper, F.; Rijnen, M.; Vermeulen, S.; Broerse, J. Policy brief on the state of the art on RRI and a working definition of RRI. In RRI Tools: Fostering Responsible Research and Innovation; Athena Institute: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014; Available online: https://www.rri-tools.eu/documents/10184/107098/RRITools_D1.1-RRIPolicyBrief.pdf/c246dc97-802f-4fe7-a230-2501330ba29b (accessed on 1 November 2018).

- Nilsson, A. Making norms to tackle global challenges: The role of intergovernmental organisations. Res. Policy 2017, 46, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spangenberg, J.H. Hot air or comprehensive progress? A critical assessment of the SDGs. Sustain. Dev. 2017, 25, 311–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hin, G.; Daigney, M.; Haudebault, D.; Raskin, K.; Bouche, Y.; Pavie, X.; Carthy, D. Introduction to a Guide to Entrepreneurs and Innovation Support Organizations. EU Funded Project Report by Paris Region Enterprises and Knowledge Acceleration Responsible Innovation Meta (KARIM) Network. 2014. Available online: https://www.inclusilver.eu/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/INCluSilver-InnovationSupportServices-Handbook.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2018).

- Stahl, B.C.; Obach, M.; Yaghmaei, E.; Ikonen, V.; Chatfield, K.; Brem, A. The Responsible Research and Innovation (RRI) maturity model: Linking theory and practice. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubberink, R.; Blok, V.; van Ophem, J.; Omta, O. Lessons for Responsible Innovation in the business context: A systematic literature review of responsible, social and sustainable innovation practices. Sustainability 2017, 9, 721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auer, A.; Jarmai, K. Implementing Responsible Research and Innovation practices in SMEs: Insights into drivers and barriers from the Austrian medical device sector. Sustainability 2017, 10, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, M.; Lazonick, W. Who Invests in the High-Tech Knowledge Base? Institute for New Economic Thinking, Working Group on the Political Economy of Distribution, The Academic-Industry Research Network: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014; Available online: http://www.theairnet.org/v3/backbone/uploads/2014/05/AIR-WP14.0901_Hopkins_Lazonick_High-TechKnowledgeBase.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2018).

- Lazonick, W.; Mazzucato, M. The risk-reward nexus in the innovation-inequality relationship: Who takes the risks? Who gets the rewards? Ind. Corp. Chang. 2013, 22, 1093–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehoux, P.; Daudelin, G.; Williams-Jones, B.; Denis, J.-L.; Longo, C. How do business model and health technology design influence each other? Insights from a longitudinal case study of three academic spin-offs. Res. Policy 2014, 43, 1025–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehoux, P.; Miller, F.; Daudelin, G.; Urbach, D. How venture capitalists decide which new medical technologies come to exist. Sci. Public Policy 2015, 43, 375–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radjou, N. Frugal Innovation: The Engine of Sustainable Development. How to Achieve Better Healthcare for More People at Lower Cost. 2015. Available online: http://ic2030.org/2015/07/frugal-innovation/ (accessed on 1 November 2018).

- Fineberg, H.V. A successful and sustainable health system—How to get there from here. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 366, 1020–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dambrin, C.; Lambert, C.; Sponem, S. Control and change—Analysing the process of institutionalisation. Manag. Account. Res. 2007, 18, 172–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehoux, P.; Roncarolo, F.; Rocha Oliveira, R.; Pacifico Silva, H. Medical innovation and the sustainability of health systems: A historical perspective on technological change in health. Health Serv. Manag. Res. 2016, 29, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, C.A.; Acharya, T.; Yach, D. Technological and social innovation: A unifying new paradigm for global health. Health Aff. 2007, 26, 1052–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, V.; King, L. Betting on hepatitis c: How financial speculation in drug development influences access to medicines. BMJ Br. Med. J. 2016, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morhason-Bello, I.O.; Odedina, F.; Rebbeck, T.R.; Harford, J.; Dangou, J.M.; Denny, L.; Adewole, I.F. Challenges and opportunities in cancer control in Africa: A perspective from the african organisation for research and training in cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2013, 14, e142–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pramesh, C.S.; Badwe, R.A.; Borthakur, B.B.; Chandra, M.; Raj, E.H.; Kannan, T.; Kalwar, A.; Kapoor, S.; Malhotra, H.; Nayak, S.; et al. Delivery of affordable and equitable cancer care in India. Lancet Oncol. 2014, 15, e223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlton, M.; Schlichting, J.; Chioreso, C.; Ward, M.; Vikas, P. Challenges of rural cancer care in the United States. Oncology 2015, 29, 633–640. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Macdonnell, M.; Darzi, A. A key to slower health spending growth worldwide will be unlocking innovation to reduce the labor-intensity of care. Health Aff. 2013, 32, 653–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strezov, V.; Evans, A.; Evans, T.J. Assessment of the economic, social and environmental dimensions of the indicators for sustainable development. Sustain. Dev. 2017, 25, 242–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimaldi, R.; Kenney, M.; Siegel, D.S.; Wright, M. 30 years after bayh–dole: Reassessing academic entrepreneurship. Res. Policy 2011, 40, 1045–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faria, A.P.; Barbosa, N. Does venture capital really foster innovation? Econ. Lett. 2014, 122, 129–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L. The most profitable industries in 2016. Forbes, 21 December 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lehoux, P.; Miller, F.A.; Daudelin, G.; Denis, J.L. Providing value to new health technology: The early contribution of entrepreneurs, investors, and regulatory agencies. Int. J. Health Policy Manag. 2017, 6, 509–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levänen, J.; Hossain, M.; Lyytinen, T.; Hyvärinen, A.; Numminen, S.; Halme, M. Implications of frugal innovations on sustainable development: Evaluating water and energy innovations. Sustainability 2015, 8, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colquitt, J.A.; Zapata-Phelan, C.P. Trends in theory building and theory testing: A five-decade study of the academy of management journal. Acad. Manag. J. 2007, 50, 1281–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morlacchi, P.; Martin, B.R. Emerging Challenges for Science, Technology and Innovation Policy Research: A Reflexive Overview; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Amanatidou, E.; Butter, M.; Carabias, V.; Könnölä, T.; Leis, M.; Saritas, O.; Schaper-Rinkel, P.; van Rij, V. On concepts and methods in horizon scanning: Lessons from initiating policy dialogues on emerging issues. Sci. Public Policy 2012, 39, 208–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douw, K.; Vondeling, H.; Eskildsen, D.; Simpson, S. Use of the Internet in scanning the horizon for new and emerging health technologies: A survey of agencies involved in horizon scanning. J. Med. Internet Res. 2003, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennato, D.; Rossi, L.; Giglietto, F. The open laboratory: Limits and possibilities of using Facebook, Twitter, and Youtube as a research data source. In Methods for Analyzing Social Media; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; pp. 19–33. [Google Scholar]

- Palomino, M.A.; Bardsley, S.; Bown, K.; De Lurio, J.; Ellwood, P.; Holland-Smith, D.; Huggins, B.; Vincenti, A.; Woodroof, H.; Owen, R. Web-based horizon scanning: Concepts and practice. Foresight 2012, 14, 355–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cammack, V.; Byrne, K. Accelerating a network model of care: Taking a social innovation to scale. Technol. Innov. Manag. Rev. 2012, 2, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umberson, D.; Karas Montez, J. Social relationships and health: A flashpoint for health policy. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2010, 51, S54–S66. Available online: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0022146510383501 (accessed on 1 November 2018). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howard, C.; Rose, C.L.; Trouton, K.; Stamm, H.; Marentette, D.; Kirkpatrick, N.; Karalic, S.; Fernandez, R.; Paget, J. Flow (finding lasting options for women): Multicentre randomized controlled trial comparing tampons with menstrual cups. Can. Fam. Phys. 2011, 57, e208–e215. [Google Scholar]

- Sundqvist, J. A Cup of Freedom?: A Study of the Menstrual Cup’s Impact on Girls’ Capabilities; Linnaeus University: Växjö, Sweden, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- WEN. Seeing Red—Sanitary Protection & the Environment, Briefing; Women’s Environment Network (WEN): London, UK, 2012; Available online: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/559d276fe4b0a65ec3938057/t/560d0280e4b079cb072e979e/1443693184604/environmenstrualweb14.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2018).

- Pozelli, R. Une Innovation Qui Donne de la Voix! Blogue Hinnovic. 2017. Available online: http://www.hinnovic.org/solar-ear-une-innovation-qui-donne-de-la-voix/ (accessed on 20 October 2018).

- Whitmee, S.; Haines, A.; Beyrer, C.; Boltz, F.; Capon, A.G.; de Souza Dias, B.F.; Ezeh, A.; Frumkin, H.; Gong, P.; Head, P. Safeguarding human health in the anthropocene epoch: Report of the Rockefeller Foundation–Lancet Commission on planetary health. Lancet 2015, 386, 1973–2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prime, M.; Attaelmanan, I.; Imbuldeniya, A.; Harris, M.; Darzi, A.; Bhatti, Y. From Malawi to Middlesex: The case of the arbutus drill cover system as an example of the cost-saving potential of frugal innovations for the UK NHS. BMJ Innov. 2018, 4, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsyth, T.; Johnson, C. Elinor ostrom’s legacy: Governing the commons and the rational choice controversy. Dev. Chang. 2014, 45, 1093–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohnsack, R.; Pinkse, J.; Kolk, A. Business models for sustainable technologies: Exploring business model evolution in the case of electric vehicles. Res. Policy 2014, 43, 284–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boons, F.; Lüdeke-Freund, F. Business models for sustainable innovation: State-of-the-art and steps towards a research agenda. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 45, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendell, M. Reflections on the evolving landscape of social enterprise in North America. Policy Soc. 2010, 29, 243–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weerawardena, J.; Mort, G.S. Investigating social entrepreneurship: A multidimensional model. J. World Bus. 2006, 41, 21–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canadian Task Force on Social Finance. Mobilizing Private Capital for Public Good. 2010. Available online: https://www.marsdd.com/mars-library/mobilizing-private-capital-for-public-good-canadian-task-force-on-social-finance/ (accessed on 20 October 2018).

- Abu-Saifan, S. Social entrepreneurship: Definition and boundaries. Technol. Innov. Manag. Rev. 2012, 2, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emerson, J. The blended value proposition: Integrating social and financial returns. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2003, 45, 35–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auerswald, P. Creating Social Value. Stanford Social Innovation Review. 2009, pp. 51–55. Available online: https://ssir.org/articles/entry/creating_social_value (accessed on 1 November 2018).

- Chesbrough, H.; Rosenbloom, R.S. The role of the business model in capturing value from innovation: Evidence from Xerox Corporation’s technology spin-off companies. Ind. Corp. Chang. 2002, 11, 529–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demil, B.; Lecocq, X. Business model evolution: In search of dynamic consistency. Long Range Plan. 2010, 43, 227–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirtz, B.W.; Pistoia, A.; Ullrich, S.; Göttel, V. Business models: Origin, development and future research perspectives. Long Range Plan. 2016, 49, 36–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doherty, B.; Haugh, H.; Lyon, F. Social enterprises as hybrid organizations: A review and research agenda. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2014, 16, 417–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stilgoe, J.; Owen, R.; Macnaghten, P. Developing a framework for responsible innovation. Res. Policy 2013, 42, 1568–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burget, M.; Bardone, E.; Pedaste, M. Definitions and conceptual dimensions of Responsible Research and Innovation: A literature review. Sci. Eng. Ethics 2017, 23, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Olmen, J.; Criel, B.; Van Damme, W.; Marchal, B.; Van Belle, S.; Van Dormael, M.; Hoerée, T.; Pirard, M.; Kegels, G. Analysing health systems to make them stronger. Stud. Health Serv. Organ. Policy 2010, 27, 2–98. [Google Scholar]

- Roncarolo, F.; Boivin, A.; Denis, J.-L.; Hébert, R.; Lehoux, P. What do we know about the needs and challenges of health systems? A scoping review of the international literature. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2017, 17, 636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antadze, N.; Westley, F.R. Impact metrics for social innovation: Barriers or bridges to radical change? J. Soc. Entrep. 2012, 3, 133–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudon, M.; Labie, M.; Reichert, P. What is a fair level of profit for social enterprise? Insights from microfinance. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajer, M.; Nilsson, M.; Raworth, K.; Bakker, P.; Berkhout, F.; de Boer, Y.; Rockström, J.; Ludwig, K.; Kok, M. Beyond cockpit-ism: Four insights to enhance the transformative potential of the sustainable development goals. Sustainability 2015, 7, 1651–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuong, Q.-H. The (ir) rational consideration of the cost of science in transition economies. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2018, 2, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ait Sidhoum, A.; Serra, T. Corporate sustainable development. Revisiting the relationship between corporate social responsibility dimensions. Sustain. Dev. 2018, 26, 365–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Country of Origin | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| United States | 479 | 46.7 |

| Canada | 17 | 16.2 |

| United Kingdom | 11 | 10.5 |

| India | 7 | 6.7 |

| Norway | 3 | 2.9 |

| Brazil | 3 | 2.9 |

| France | 2 | 1.9 |

| Others 1 | 13 | 12.4 |

| Total | 105 | 100 |

| Target Region | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Africa | 28 | 22.6 |

| South Asia | 22 | 17.7 |

| Unspecified | 18 | 14.5 |

| Low income countries | 17 | 13.7 |

| Global | 14 | 11.3 |

| Central and South America | 13 | 10.5 |

| North America | 7 | 5.6 |

| Europe | 4 | 3.2 |

| Australia | 1 | 0.8 |

| Total | 124 | 100 |

| Indication | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| New-born complications | 17 | 15.5 |

| Reduced mobility & limb amputation | 16 | 14.5 |

| Malaria, infectious diseases & diarrheal diseases | 12 | 10.9 |

| Pregnancy & delivery complications | 10 | 9.1 |

| Visual & hearing dysfunctions | 9 | 8.2 |

| Tuberculosis & respiratory diseases | 8 | 7.3 |

| Access to care & drugs | 8 | 7.3 |

| HIV/AIDS | 7 | 6.4 |

| Cardiovascular diseases | 4 | 3.6 |

| Cancer | 3 | 2.7 |

| Anemia | 2 | 1.8 |

| Diabetes | 2 | 1.8 |

| Other 1 | 12 | 10.9 |

| Total | 110 | 100 |

| Sustainable Development Goal | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| SDG3. Good health & well-being | 105 | 100 |

| SDG10. Reduced inequalities | 91 | 87 |

| SDG17. Partnerships for the goals | 57 | 54 |

| SDG1. No poverty | 16 | 15 |

| SDG4. Quality education | 12 | 11 |

| SDG11. Sustainable cities & communities | 9 | 9 |

| SDG7. Affordable & clean energy | 7 | 7 |

| SDG9. Industry, innovation & infrastructure | 6 | 6 |

| SDG6. Clean water & sanitation | 5 | 5 |

| SDG5. Gender equality | 3 | 3 |

| SDG15. Life on land | 2 | 2 |

| SDG2. Zero hunger | 1 | 1 |

| SDG8. Decent work & economic growth | 1 | 1 |

| SDG12. Responsible consumption & production | 1 | 1 |

| SDG13. Climate action | 1 | 1 |

| SDG14. Life below water | 1 | 1 |

| SDG16. Peace, justice & institutions | 0 | 0 |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lehoux, P.; Pacifico Silva, H.; Pozelli Sabio, R.; Roncarolo, F. The Unexplored Contribution of Responsible Innovation in Health to Sustainable Development Goals. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4015. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10114015

Lehoux P, Pacifico Silva H, Pozelli Sabio R, Roncarolo F. The Unexplored Contribution of Responsible Innovation in Health to Sustainable Development Goals. Sustainability. 2018; 10(11):4015. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10114015

Chicago/Turabian StyleLehoux, Pascale, Hudson Pacifico Silva, Renata Pozelli Sabio, and Federico Roncarolo. 2018. "The Unexplored Contribution of Responsible Innovation in Health to Sustainable Development Goals" Sustainability 10, no. 11: 4015. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10114015

APA StyleLehoux, P., Pacifico Silva, H., Pozelli Sabio, R., & Roncarolo, F. (2018). The Unexplored Contribution of Responsible Innovation in Health to Sustainable Development Goals. Sustainability, 10(11), 4015. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10114015