Blue and Green Spaces as Therapeutic Landscapes: Health Effects of Urban Water Canal Areas of Isfahan

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature Review

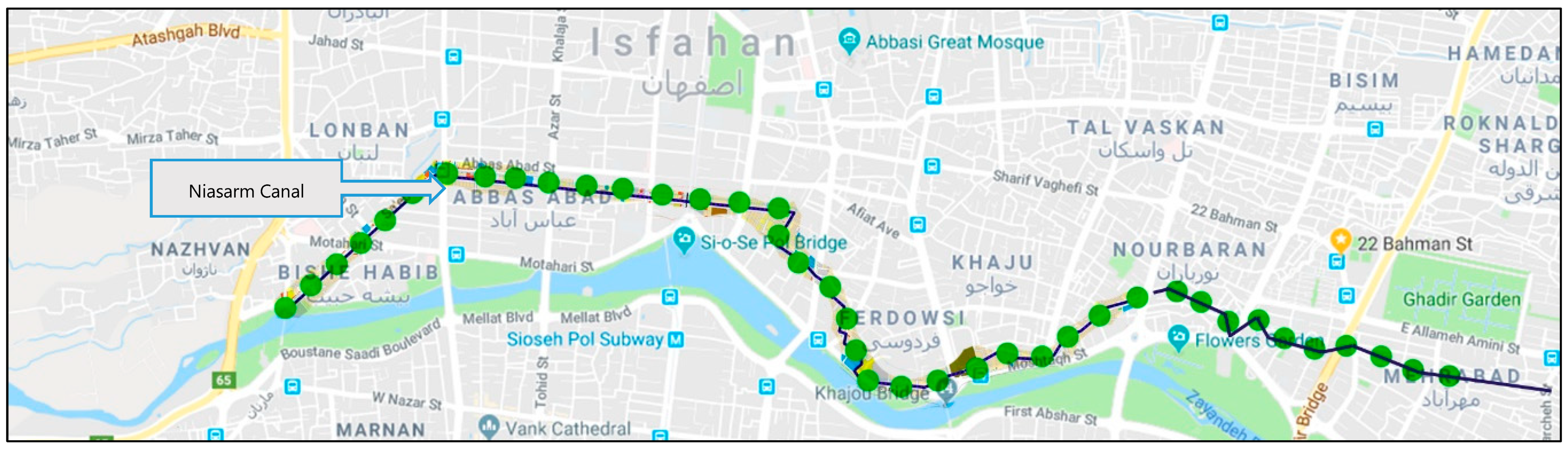

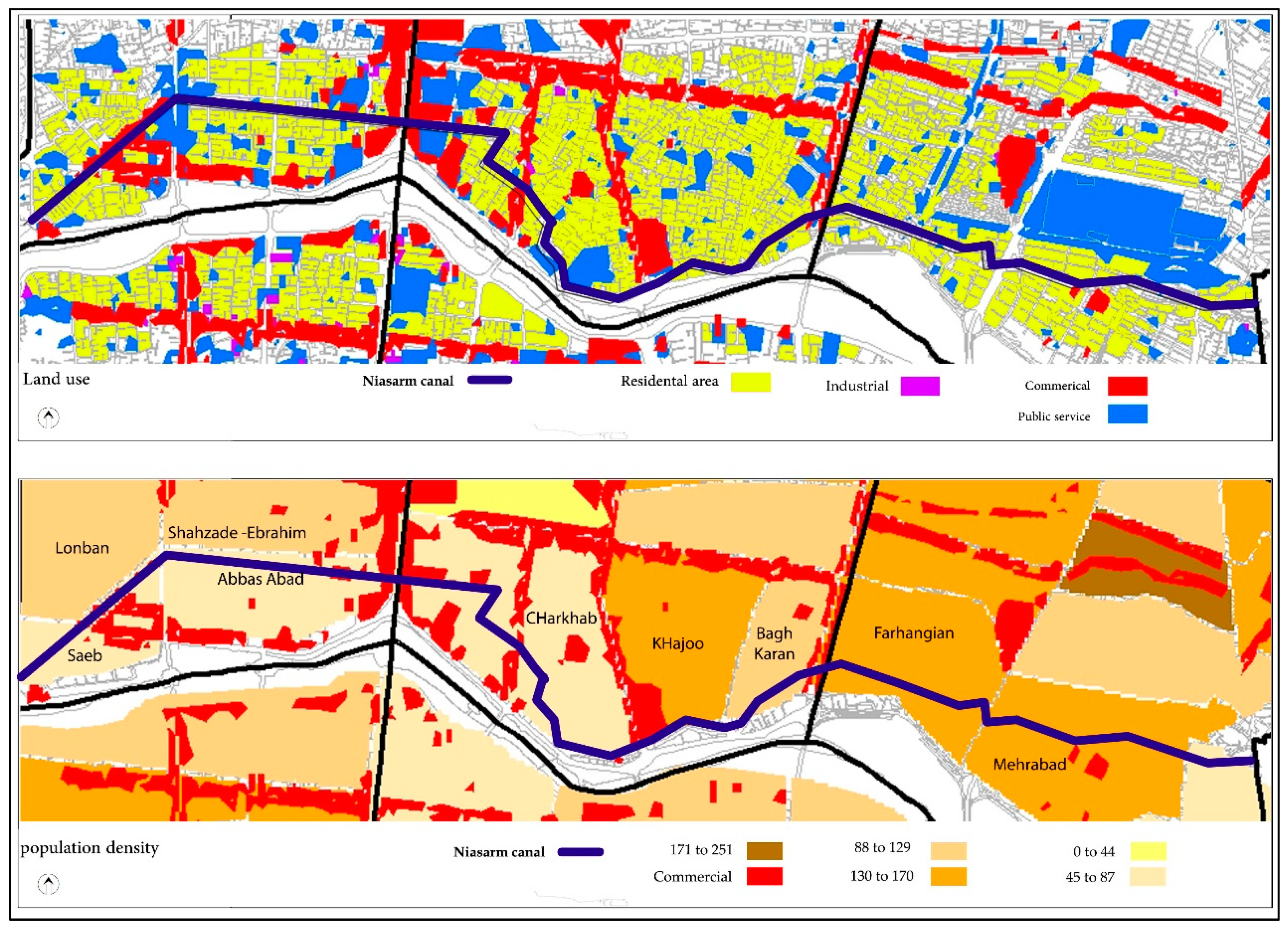

2.2. Case Study

2.3. Method and Data Collection

2.4. Data Analysis

- ▪

- Theme 1: Canal’s importance in promoting active life;

- ▪

- Theme 2: Sense of rehabilitation, calmness, and concentration alongside the canal;

- ▪

- Theme 3: Canal as the core of social life in neighborhoods;

- ▪

- Theme 4: Place identity and cultural heritage.

3. Results

3.1. Canal’s Importance in Promoting Activities in Everyday Life

“The canal in every street is a park for my daily walk; firstly, it is near my house, also it has a direct and green route that encourages me to walk.”(a 57-year-old woman)

“Canal corridors can provide opportunities for recreation as part of daily life allowing stress relief and enjoyment as well as activities such as walking, cycling and exercise. However, when the canal runs dry we feel sad.”(a 25-year-old woman)

“Where do I find better than the canal for walking? fresh air, usually cooler than the alleys, it is the best place to walk and makes you feel healthier.”(a 67-year-old man)

“The canal is the best path to walk, because it is safe and uninterrupted, and it does not feel unsafe walking along its path in the afternoons.”(a 35-year-old woman)

“Water can be a breeding zone for pesky insects and other animals. Mosquitoes can be a major nuisance, depending on location and time of the day.”(a 31-year-old man)

3.2. A Sense of Restoration, Relaxation, and Concentration in the Canal

“When I come into this atmosphere, I feel that I can easily focus on subjects, looking at trees and it makes me relieved.”(a 42-year-old woman)

“The sound of water at times when the canal has high water levels makes me feel relaxed and happy.”(a 70-year-old woman)

“When I spend time at the canal, it makes me feel relieved from my daily life and helps me to escape from economic and social stresses I go through.”(a 45-year-old man)

3.3. Canal as the Core of Social Life in Neighborhoods

“We have spent our family vocation alongside the canal, and we still continue to come together in the canal annually, even when the canal does not have water in the summer.”(a 62-year-old woman)

“When the weather is good, the canal is full of people from the neighborhood. Women, children, and old people all prefer to socialize together alongside the canal.”(a 45-years-old man)

3.4. Place Identity and Cultural Heritage

“This canal revives good childhood memories for me, whenever I sit next to the water, I become young again and I feel euphoric.”(an 82-year-old man)

“Everyone has a really strong empathy with water and the canal and its history and its current environment, but we are worried about the poor management of this water canal.”(an 80-year-old man)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| No. | Survey Questions |

|---|---|

| 1 | Age |

| 2 | Gender |

| 3 | Education level |

| 4 | Income level |

| 5 | Address (as in neighborhood only) |

| 6 | How frequent do you visit the canal? |

| 7 | How much time approximately do you spend on each visit? |

| 8 | Do you feel healthier and/or happier when spending time alongside the canal? If yes why? |

| 9 | Does the canal contribute to improving your physical health? If yes how? |

| 10 | Does the canal contribute to improving your mental health? If yes how? |

| 11 | Does the canal contribute to improving your social activities? If yes how? |

| 12 | What are the contributions of the canal to your life? |

| 13 | What are the contributions of the canal to the local community? |

| 14 | Do you recommend or encourage others to visit the canal? If yes/no why? |

| 15 | Other comments |

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). City Health Profiles: A Review of Progress; World Health Organization (WHO): Geneva, Switzerland, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- De Vries, S.; Verheij, R.A.; Groenewegen, P.P.; Spreeuwenberg, P. Natural environments—Healthy environments? An exploratory analysis of the relationship between green space and health. Environ. Plan. A 2003, 35, 1717–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frumkin, H. Beyond toxicity1: Human health and the natural environment. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2001, 20, 234–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudes, O.; Kendall, E.; Yigitcanlar, T.; Pathak, V.; Baum, S. Rethinking health planning: A framework for organising information to underpin collaborative health planning. Health Inf. Manag. J. 2010, 39, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costanza, R. Toward an operational definition of ecosystem health. In Ecosystem Health: New Goals for Environmental Management; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1992; pp. 239–269. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, F.; Li, Z. A model of ecosystem health and its application. Ecol. Model. 2003, 170, 55–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yigitcanlar, T. Planning for smart urban ecosystems: Information technology applications for capacity building in environmental decision making. Theor. Empir. Res. Urban Manag. 2009, 4, 5–21. [Google Scholar]

- Yigitcanlar, T.; Dizdaroglu, D. Ecological approaches in planning for sustainable cities: A review of the literature. Glob. J. Environ. Sci. Manag. 2014, 1, 159–188. [Google Scholar]

- Takano, T.; Nakamura, K.; Watanabe, M. Urban residential environments and senior citizens’ longevity in megacity areas: The importance of walkable green spaces. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2002, 56, 913–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, A.; Takano, T.; Nakamura, K.; Takeuchi, S. Health levels influenced by urban residential conditions in a megacity—Tokyo. Urban Stud. 1996, 33, 879–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teimouri, R.; Yigitcanlar, T. An approach towards effective ecological planning: Quantitative analysis of urban green space characteristics. Glob. J. Environ. Sci. Manag. 2018, 4, 195–206. [Google Scholar]

- Völker, S.; Kistemann, T. Developing the urban blue: Comparative health responses to blue and green urban open spaces in Germany. Health Place 2015, 35, 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finlay, J.; Franke, T.; McKay, H.; Sims-Gould, J. Therapeutic landscapes and wellbeing in later life: Impacts of blue and green spaces for older adults. Health Place 2015, 34, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braubach, M.; Egorov, A.; Mudu, P.; Wolf, T.; Thompson, C.W.; Martuzzi, M. Effects of urban green space on environmental health, equity and resilience. In Nature-Based Solutions to Climate Change Adaptation in Urban Areas; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2017; pp. 187–205. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, A.C.; Jordan, H.C.; Horsley, J. Value of urban green spaces in promoting healthy living and wellbeing: Prospects for planning. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2015, 8, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goonetilleke, A.; Yigitcanlar, T.; Ayoko, G.; Egodawatta, P. Sustainable Urban Water Environment: Climate, Pollution and Adaptation; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Rostami, R.; Lamit, H.; Khoshnava, S.M.; Rostami, R.; Rosley, M.S. Sustainable cities and the contribution of historical urban green spaces: A case study of historical persian gardens. Sustainability 2015, 7, 13290–13316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhshi, M. Natural arteries of Isfahan the give identity to this city. Int. Res. J. Appl. Basic Sci. 2014, 8, 534–539. [Google Scholar]

- Gesler, W.J. Healing Places; Rowman and Littlefield: Lanham, MD, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Gesler, W. Lourdes: Healing in a place of pilgrimage. Health Place 1996, 2, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattell, V.; Dines, N.; Gesler, W.; Curtis, S. Mingling, observing, and lingering: Everyday public spaces and their implications for well-being and social relations. Health Place 2008, 14, 544–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reshadat, S.; Zangeneh, A.; Saeidi, S.; Teimouri, R.; Yigitcanlar, T. Measures of spatial accessibility to health centers: Investigating urban and rural disparities in Kermanshah, Iran. J. Public Health 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakefield, S.; McMullan, C. Healing in places of decline: (Re)imagining everyday landscapes in Hamilton, Ontario. Health Place 2005, 11, 299–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smyth, F. Medical geography: Therapeutic places, spaces, and networks. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2005, 29, 488–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoly, E.; Dadvand, P.; Forns, J.; López-Vicente, M.; Basagaña, X.; Julvez, J.; Alvarez-Pedrerol, M.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M.J.; Sunyer, J. Green and blue spaces and behavioral development in Barcelona schoolchildren: The BREATHE project. Environ. Health Perspect. 2014, 122, 1351–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berman, M.G.; Kross, E.; Krpan, K.M.; Askren, M.K.; Burson, A.; Deldin, P.J.; Kaplan, S.; Sherdell, L.; Gotlib, I.H.; Jonides, J. Interacting with nature improves cognition and affect for individuals with depression. J. Affect. Disord. 2012, 140, 300–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nutsford, D.; Pearson, A.L.; Kingham, S. An ecological study investigating the association between access to urban green space and mental health. Public Health 2013, 127, 1005–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maas, J.; Verheij, R.A.; de Vries, S.; Spreeuwenberg, P.; Schellevis, F.G.; Groenewegen, P.P. Morbidity is related to a green living environment. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2009, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearce, J.; Mitchell, R.; Shortt, N. Place, space, and health inequalities. In Health Inequalities: Critical Perspectives; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016; pp. 192–205. [Google Scholar]

- Bolund, P.; Hunhammar, S. Ecosystem services in urban areas. Ecol. Econ. 1999, 29, 293–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Herzele, A.; Wiedemann, T. A monitoring tool for the provision of accessible and attractive urban green spaces. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2003, 63, 109–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovasi, G.S.; Lemaitre, R.N.; Siscovick, D.S.; Dublin, S.; Bis, J.C.; Lumley, T.; Heckbert, S.R.; Smith, N.L.; Psaty, B.M. Amount of leisure-time physical activity and risk of nonfatal myocardial infarction. Ann. Epidemiol. 2007, 17, 410–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- James, P.; Tzoulas, K.; Adams, M.D.; Barber, A.; Box, J.; Breuste, J.; Elmqvist, T.; Frith, M.; Gordon, C.; Greening, K.L.; et al. Towards an integrated understanding of green space in the European built environment. Urban For. Urban Green. 2009, 8, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, D.J.; Crane, D.E.; Stevens, J.C. Air pollution removal by urban trees and shrubs in the United States. Urban For. Urban Green. 2006, 4, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, F.E. Coping with poverty: Impacts of environment and attention in the inner city. Environ. Behav. 2001, 33, 5–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedict, M.; McMahon, E. Green Infrastructure: Smart Conservation for the 21st Century; Sprawl Watch Clearinghouse: Washington, DC, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Dizdaroglu, D.; Yigitcanlar, T.; Dawes, L. A micro-level indexing model for assessing urban ecosystem sustainability. Smart Sustain. Built Environ. 2012, 1, 291–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yigitcanlar, T. Sustainable Urban and Regional Infrastructure Development: Technologies, Applications and Management: Technologies, Applications and Management; IGI Global: Hersey, PA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Yigitcanlar, T. Rethinking Sustainable Development: Urban Management, Engineering, and Design; IGI Global: Hersey, PA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- White, M.P.; Alcock, I.; Wheeler, B.W.; Depledge, M.H. Coastal proximity and health: A fixed effects analysis of longitudinal panel data. Health Place 2013, 23, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Triguero-Mas, M.; Dadvand, P.; Cirach, M.; Martínez, D.; Medina, A.; Mompart, A.; Basagaña, X.; Gražulevičienė, R.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M.J. Natural outdoor environments and mental and physical health: Relationships and mechanisms. Environ. Int. 2015, 77, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foley, R.; Kistemann, T. Blue space geographies: Enabling health in place. Health Place 2015, 35, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorn, M.; Laws, G. Social theory, body politics, and medical geography: Extending Kearns’s invitation. Prof. Geogr. 1994, 46, 106–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longhurst, R. Fat bodies: Developing geographical research agendas. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2005, 3, 247–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, B.W.; White, M.; Stahl-Timmins, W.; Depledge, M.H. Does living by the coast improve health and wellbeing? Health Place 2012, 18, 1198–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kistemann, T.; Völker, S.; Lengen, C. Stadtblau–Die Gesundheitliche Bedeutung von Gewässern in Urbanen Raum; Bedeutung von Stadtgrün für Gesundheit und Wohlbefinden; Natur-und Umweltschutz Akademie: Recklinghausen, Germany, 2010; pp. 61–66. [Google Scholar]

- Roe, J.J.; Aspinall, P.A. Adolescents’ daily activities and the restorative niches that support them. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2012, 9, 3227–3244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, M.P.; Pahl, S.; Ashbullby, K.; Herbert, S.; Depledge, M.H. Feelings of restoration from recent nature visits. J. Environ. Psychol. 2013, 35, 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashbullby, K.J.; Pahl, S.; Webley, P.; White, M.P. The beach as a setting for families’ health promotion: A qualitative study with parents and children living in coastal regions in Southwest England. Health Place 2013, 23, 138–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeon, J.Y.; Lee, P.J.; You, J.; Kang, J. Perceptual assessment of quality of urban soundscapes with combined noise sources and water sounds. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2010, 127, 1357–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coensel, B.D.; Vanwetswinkel, S.; Botteldooren, D. Effects of natural sounds on the perception of road traffic noise. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2011, 129, EL148–EL153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voelker, S.; Baumeister, H.; Classen, T.; Hornberg, C.; Kistemann, T. Evidence for the temperature-mitigating capacity of urban blue space—A health geographic perspective. Erdkunde 2013, 1, 355–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, J.; Pretty, J. What is the best dose of nature and green exercise for improving mental health? A multi-study analysis. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010, 44, 3947–3955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yigitcanlar, T.; Foth, M.; Kamruzzaman, M. Towards post-anthropocentric cities: Reconceptualizing smart cities to evade urban ecocide. J. Urban Technol. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haeffner, M.; Jackson-Smith, D.; Buchert, M.; Risley, J. Accessing blue spaces: Social and geographic factors structuring familiarity with, use of, and appreciation of urban waterways. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2017, 167, 136–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corti, L. Clive Seale (1999): The quality of qualitative research. Forum Qual. Sozialforschung/Forum Qual. Soc. Res. 2000, 1, 46. [Google Scholar]

- Baum, S.; Kendall, E.; Muenchberger, H.; Gudes, O.; Yigitcanlar, T. Geographical information systems: An effective planning and decision-making platform for community health coalitions in Australia? Health Inf. Manag. J. 2010, 39, 28–33. [Google Scholar]

- Flick, U. An Introduction to Qualitative Research; Sage: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Abraham, A.; Sommerhalder, K.; Abel, T. Landscape and well-being: A scoping study on the health-promoting impact of outdoor environments. Int. J. Public Health 2010, 55, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghalehnoee, M.; Alikhani, M. Evaluation of Isfahan’s “Madies” as greenways, with sustainable development approach: A case study of Niasarm Madi. J. Environ. Stud. 2015, 40, 52–54. [Google Scholar]

- Bowler, D.E.; Buyung-Ali, L.; Knight, T.M.; Pullin, A.S. Urban greening to cool towns and cities: A systematic review of the empirical evidence. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2010, 97, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartig, T.; van den Berg, A.E.; Hagerhall, C.M.; Tomalak, M.; Bauer, N.; Hansmann, R.; Ojala, A.; Syngollitou, E.; Carrus, G.; van Herzele, A.; et al. Health benefits of nature experience: Psychological, social and cultural processes. In Forests, Trees and Human Health; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2011; pp. 127–168. [Google Scholar]

- Milligan, C.; Gatrell, A.; Bingley, A. ‘Cultivating health’: Therapeutic landscapes and older people in northern England. Soc. Sci. Med. 2004, 58, 1781–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugiyama, T.; Thompson, C.W. Older people’s health, outdoor activity and supportiveness of neighbourhood environments. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2007, 83, 168–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, M. Control as a dimension of public-space quality. In Public Places and Spaces, Human Behavior and Environment (Advances in Theory and Research); Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1989; pp. 147–172. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, A. Changing geographies of care: Employing the concept of therapeutic landscapes as a framework in examining home space. Soc. Sci. Med. 2002, 55, 141–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lak, A.; Aghamolaei, R.; Azizkhani, E. From segregation to integration of new developments in historic contexts: Rural texture in Iran. J. Settl. Spat. Plan. 2018, 9, 59–66. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, V. Applying integrated urban water management concepts: A review of Australian experience. Environ. Manag. 2006, 37, 589–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, T. Brown, R. The water sensitive city: Principles for practice. Water Sci. Technol. 2009, 60, 673–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, A.; Pezzaniti, D.; Myers, B.; Cook, S.; Tjandraatmadja, G.; Chacko, P.; Chavoshi, S.; Kemp, D.; Leonard, R.; Koth, B.; et al. Water sensitive urban design: An investigation of current systems, implementation drivers, community perceptions and potential to supplement urban water services. Water 2016, 28, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbolino, R.; Carlucci, F.; Cirà, A.; Ioppolo, G.; Yigitcanlar, T. Efficiency of the EU regulation on greenhouse gas emissions in Italy: The hierarchical cluster analysis approach. Ecol. Indic. 2017, 81, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbolino, R.; Carlucci, F.; Simone, L.; Yigitcanlar, T.; Ioppolo, G. The policy diffusion of environmental performance in the European countries. Ecol. Indic. 2018, 89, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamruzzaman, M.; Deilami, K.; Yigitcanlar, T. Investigating the urban heat island effect of transit-oriented development in Brisbane. J. Transp. Geogr. 2018, 66, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corburn, J. Confronting the challenges in reconnecting urban planning and public health. Am. J. Public Health 2004, 94, 541–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, G.; Hansz, J.A.; Cypher, M.L. The influence of artificial water canals on residential sale prices. Apprais. J. 2005, 73, 167–174. [Google Scholar]

- Mahbub, P.; Goonetilleke, A.; Ayoko, G.; Egodawatta, P.; Yigitcanlar, T. Analysis of build-up of heavy metals and volatile organics on urban roads in Gold Coast, Australia. Water Sci. Technol. 2011, 63, 2077–2085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sansalone, J.; Buchberger, S. Partitioning and first flush of metals in urban roadway storm water. J. Environ. Eng. 1997, 123, 134–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dur, F.; Yigitcanlar, T.; Bunker, J. A spatial-indexing model for measuring neighbourhood-level land-use and transport integration. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 2014, 41, 792–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yigitcanlar, T.; Kamruzzaman, M.; Teriman, S. Neighborhood sustainability assessment: Evaluating residential development sustainability in a developing country context. Sustainability 2015, 7, 2570–2602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernald, A.; Tidwell, V.; Rivera, J.; Rodríguez, S.; Guldan, S.; Steele, C.; Ochoa, C.; Hurd, B.; Ortiz, M.; Boykin, K.; et al. Modeling sustainability of water, environment, livelihood, and culture in traditional irrigation communities and their linked watersheds. Sustainability 2012, 4, 2998–3022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gender | Count | Age Group | Count | Education | Count |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 102 | 15–35 | 18 | Primary | 36 |

| 36–45 | 60 | Secondary | 55 | ||

| 46–65 | 19 | Tertiary | 11 | ||

| 65–85 | 5 | ||||

| Male | 98 | 15–35 | 17 | Primary | 24 |

| 36–45 | 40 | Secondary | 60 | ||

| 46–65 | 32 | Tertiary | 14 | ||

| 65–85 | 9 | ||||

| Total | 200 | 200 | 200 |

| Characteristic | Frequency | Unit | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total participant population | 200 | People | 100 |

| Female participants | 102 | People | 51 |

| Male participants | 98 | People | 49 |

| Age of participants (median) | 37 | People | - |

| Education level of participants (median) | Secondary | School | - |

| Income level of participants (median) | Medium-low | Income group | - |

| Park visit frequency of participants (median) | Every 3 | Days | - |

| Time spent in each park visits by participants (median) | 45–60 | Minutes | - |

| Contributions to feel healthier and/or happier (yes) | 158 | Response: Yes | 79 |

| Contributions to physical health (yes) | 124 | Response: Yes | 62 |

| Contributions to mental health (yes) | 128 | Response: Yes | 64 |

| Contributions to social activities (yes) | 130 | Response: Yes | 65 |

| Contributions to life (yes) | 182 | Response: Yes | 91 |

| Contributions to local community (yes) | 124 | Response: Yes | 62 |

| Encourage others to visit the canal (yes) | 178 | Response: Yes | 89 |

| Concepts | N | % | Codes | Themes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fresh and clean weather | 165 | 82.5 | Comfort and relaxation | Canal’s importance in promoting active lifestyles |

| Sound of nature | 127 | 63.5 | ||

| Absence of waste, construction waste, sewage pollution | 161 | 80.5 | ||

| Privacy and comfortable | 104 | 52 | ||

| Appropriate enclosure | 142 | 71 | ||

| Easy access for all to the canal from nearby areas | 112 | 56 | ||

| Easy access to public transport stations | 142 | 71 | ||

| Sense of the distinction between spatial realms | 125 | 61.5 | ||

| Navigation sense | 142 | 71 | ||

| Ability to perceive and nobility to space | 120 | 60 | ||

| Local hangouts | 117 | 58.5 | ||

| Appropriate lighting at night | 104 | 52 | Mobility and motion | |

| Wide width for walking and running and cycling | 112 | 56 | ||

| Ease of moving people in space and lack of obstacles | 104 | 52 | ||

| Flow of water in the canal | 132 | 66 | Sensory richness | |

| Stimulate visual senses | 112 | 56 | ||

| Stimulates the senses of water and soil and plants | 112 | 56 | ||

| The sound of the birds | 109 | 54.5 | ||

| Feeling wind and water | 123 | 61.5 | ||

| Water and plant presence | 141 | 70.5 | ||

| Existence of police stations | 132 | 66 | Sense of safety and security | |

| Mixed applications | 145 | 72.5 | ||

| Lack of intrusive and informal activities | 142 | 71 | ||

| Lack of urban indifference | 111 | 55.5 | ||

| Local monitoring | 104 | 52 | ||

| Spacing and pairing | 104 | 52 | Beauty and esthetics | |

| Beautiful buildings | 117 | 85.5 | ||

| Landscapes of trees | 132 | 66 | ||

| Privacy and comfortable | 120 | 60 | Mental relaxation | Sense of rehabilitation, calmness, concentration alongside the canal |

| Adequate population density on sidewalks, stations | 131 | 65.5 | ||

| Extreme stress relief | 123 | 61.5 | ||

| Feeling focused | 132 | 66 | ||

| Sense of keeping the environment | 120 | 60 | ||

| Sense of rest and rehab | 111 | 55.5 | ||

| Feeling of independence and liberation | 111 | 55.5 | ||

| Feel the power and health in space | 131 | 65.5 | ||

| Simple and lovely space | 109 | 54.5 | Familiarity with the environment | |

| No hidden corners | 116 | 58 | ||

| Easy to understand the canal route | 123 | 61.5 | ||

| Possibility to touch the plants | 145 | 72.5 | Feeling of being in nature | |

| Variety of plant species, animals and birds | 178 | 89 | ||

| Sound of birds and water | 132 | 66 | ||

| Quality of life in the neighborhoods | 111 | 55.5 | Sense of satisfaction | Canal as the core of social life in neighborhoods |

| Satisfaction with life in the neighborhoods | 120 | 60 | ||

| Places to meet friends and acquaintances | 156 | 78 | Social interactions | |

| Local community activities | 128 | 64 | ||

| Social relationships | 104 | 52 | ||

| Permanent use of the canal | 109 | 54.5 | ||

| Presence of all residents of nearby neighborhoods | 178 | 89 | ||

| Identity of the canal, neighborhood, and city | 140 | 70 | Sense of place | Place identity and cultural heritage |

| Memories of the canal area | 87 | 43.5 | ||

| History of the city and the neighborhood | 120 | 60 | ||

| Quality of life in the city | 161 | 80.5 | ||

| Sense of belonging to the canal | 165 | 82.5 | ||

| Concerns about dryness | 178 | 89 |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vaeztavakoli, A.; Lak, A.; Yigitcanlar, T. Blue and Green Spaces as Therapeutic Landscapes: Health Effects of Urban Water Canal Areas of Isfahan. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4010. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10114010

Vaeztavakoli A, Lak A, Yigitcanlar T. Blue and Green Spaces as Therapeutic Landscapes: Health Effects of Urban Water Canal Areas of Isfahan. Sustainability. 2018; 10(11):4010. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10114010

Chicago/Turabian StyleVaeztavakoli, Amirafshar, Azadeh Lak, and Tan Yigitcanlar. 2018. "Blue and Green Spaces as Therapeutic Landscapes: Health Effects of Urban Water Canal Areas of Isfahan" Sustainability 10, no. 11: 4010. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10114010

APA StyleVaeztavakoli, A., Lak, A., & Yigitcanlar, T. (2018). Blue and Green Spaces as Therapeutic Landscapes: Health Effects of Urban Water Canal Areas of Isfahan. Sustainability, 10(11), 4010. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10114010