Spatio-Temporal Patterns and Determinants of Inter-Provincial Migration in China 1995–2015

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

3.2. Methods

4. Results

4.1. Changing Trends of Inter-Provincial Migration Volume

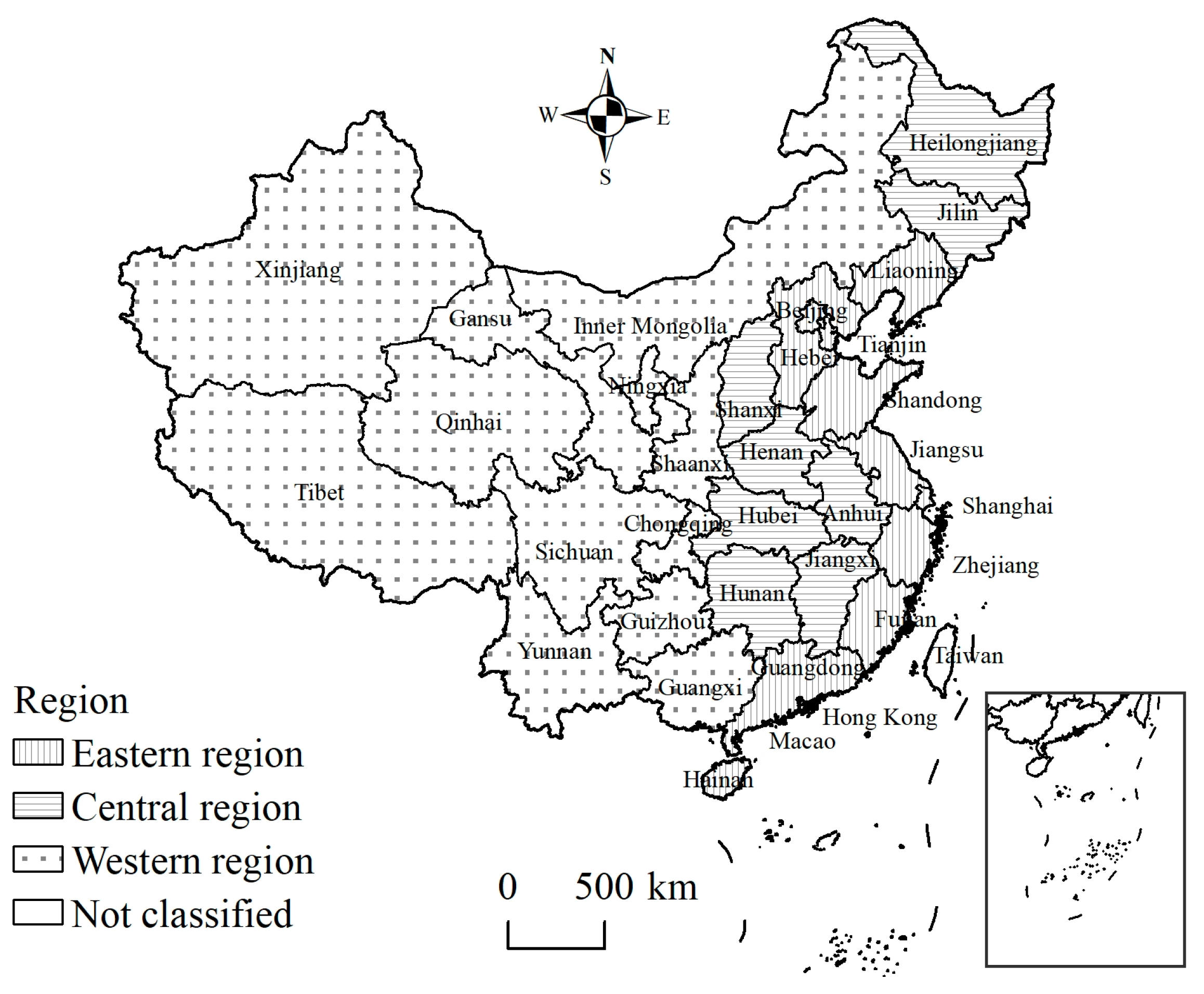

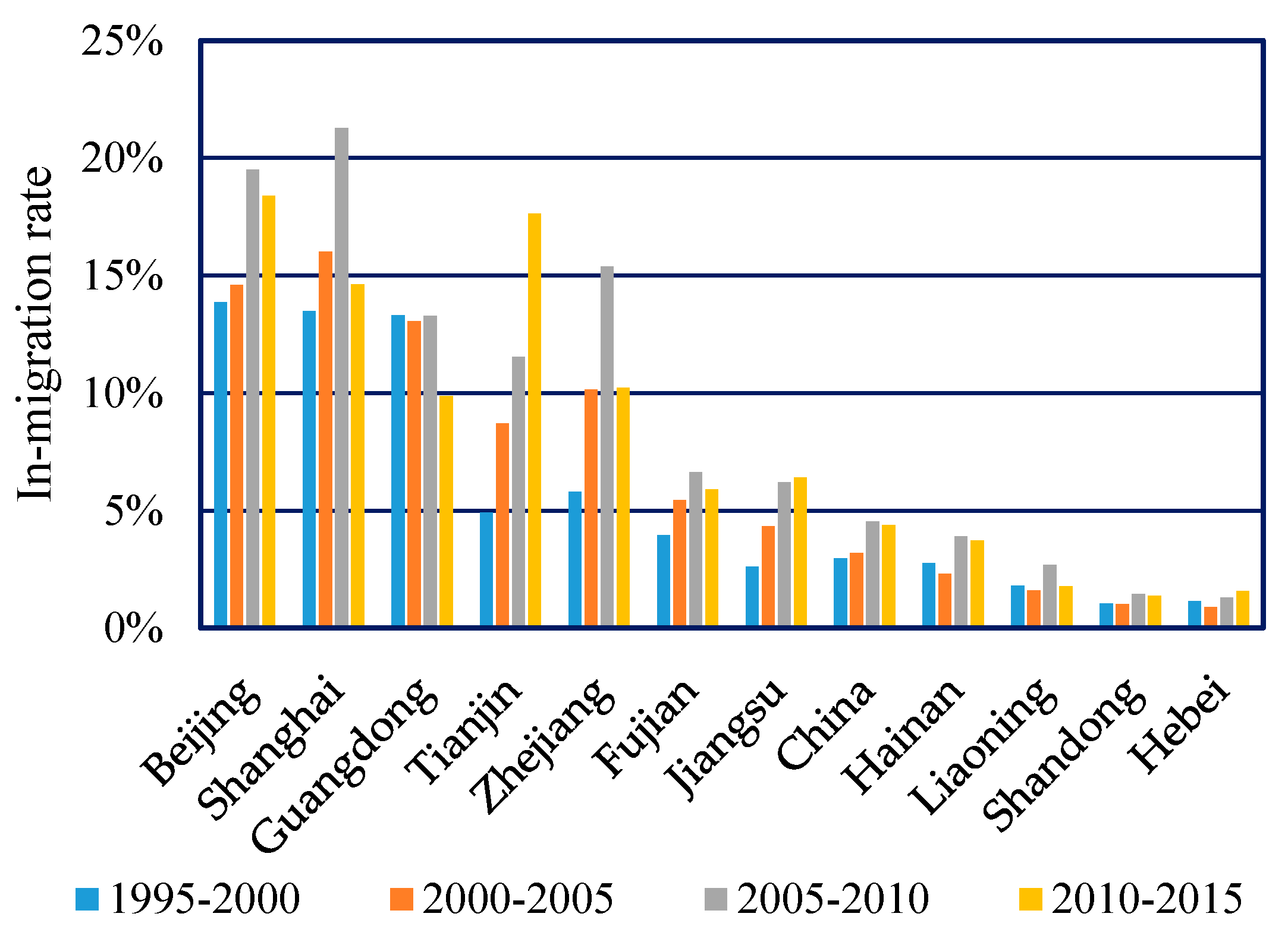

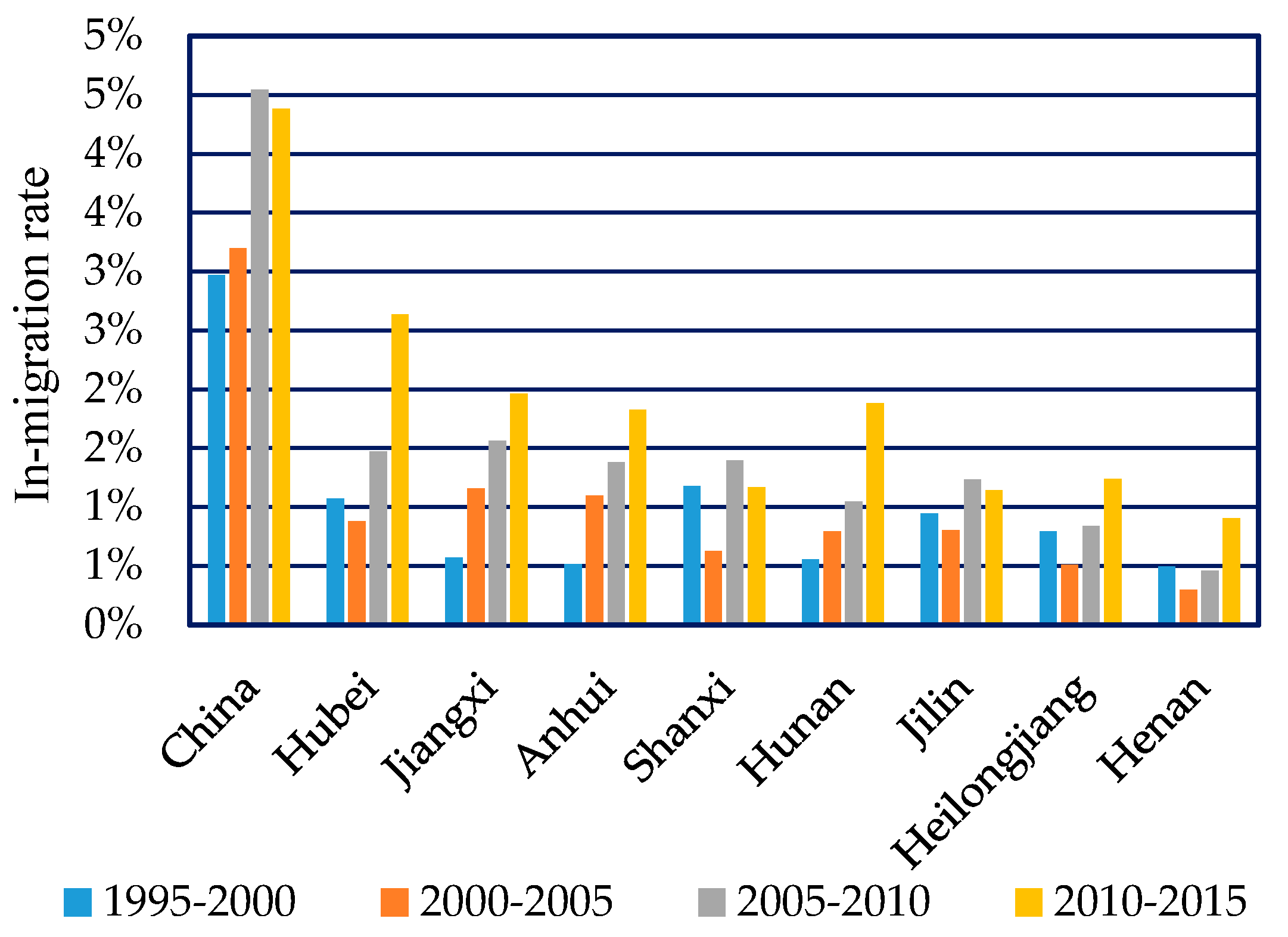

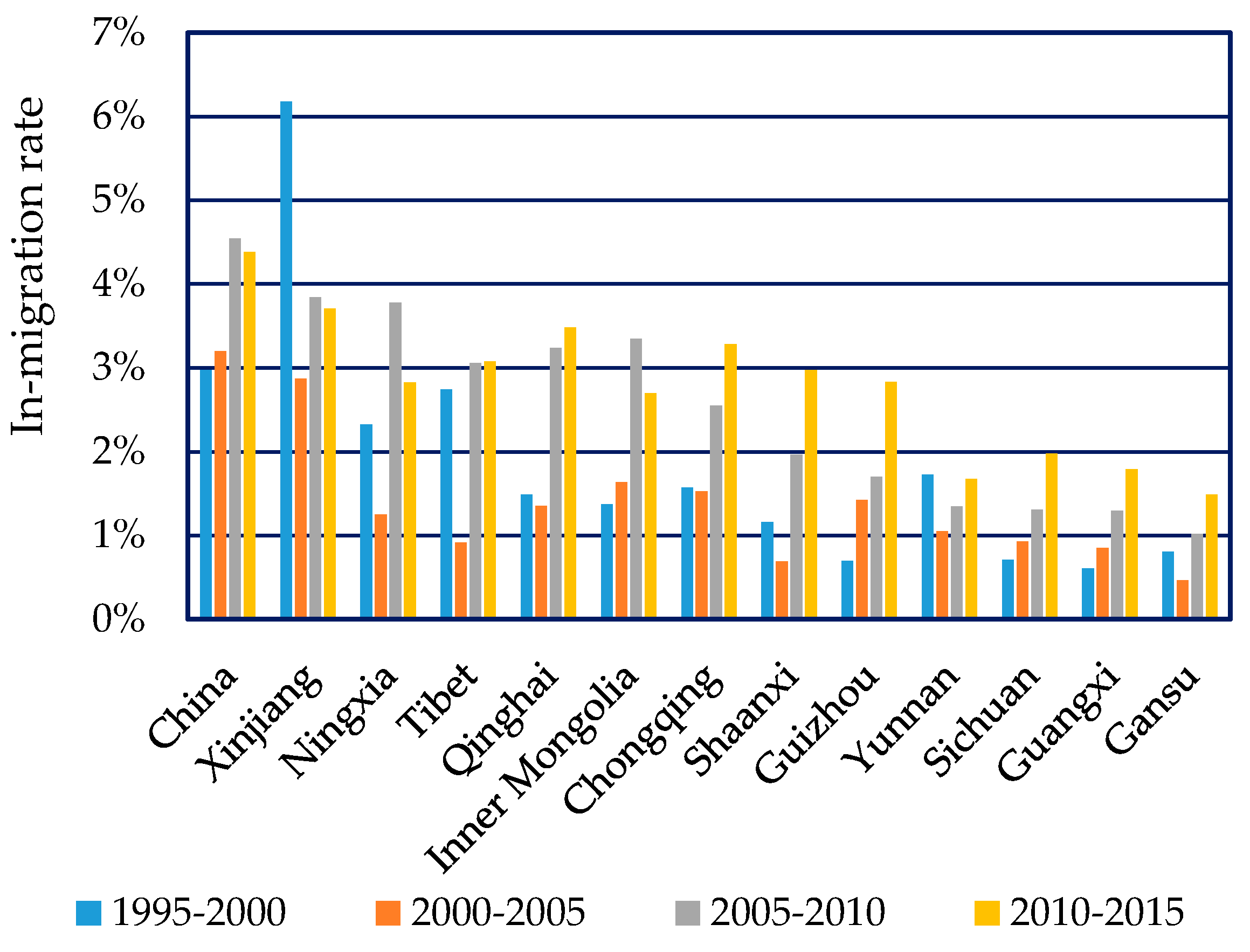

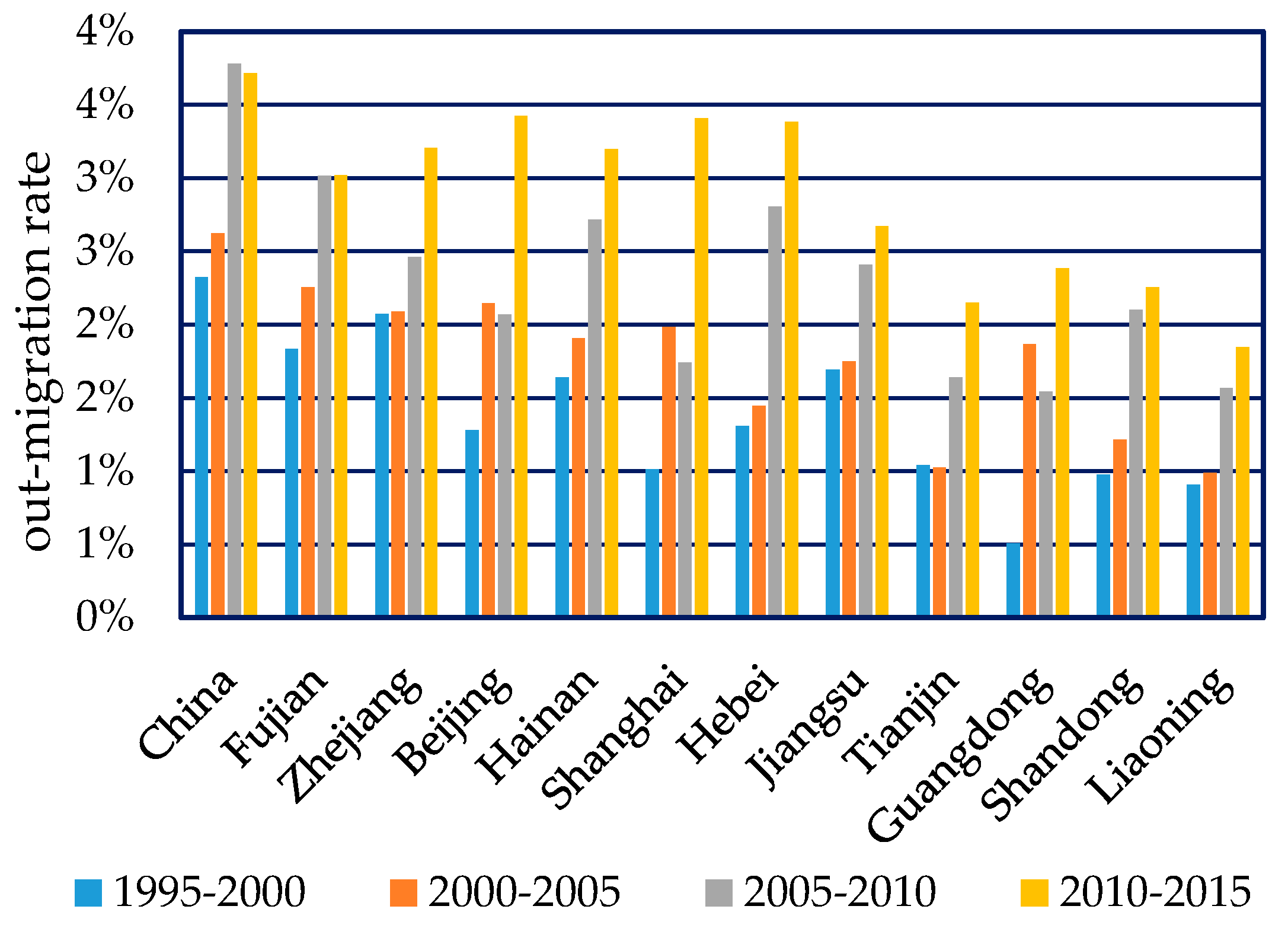

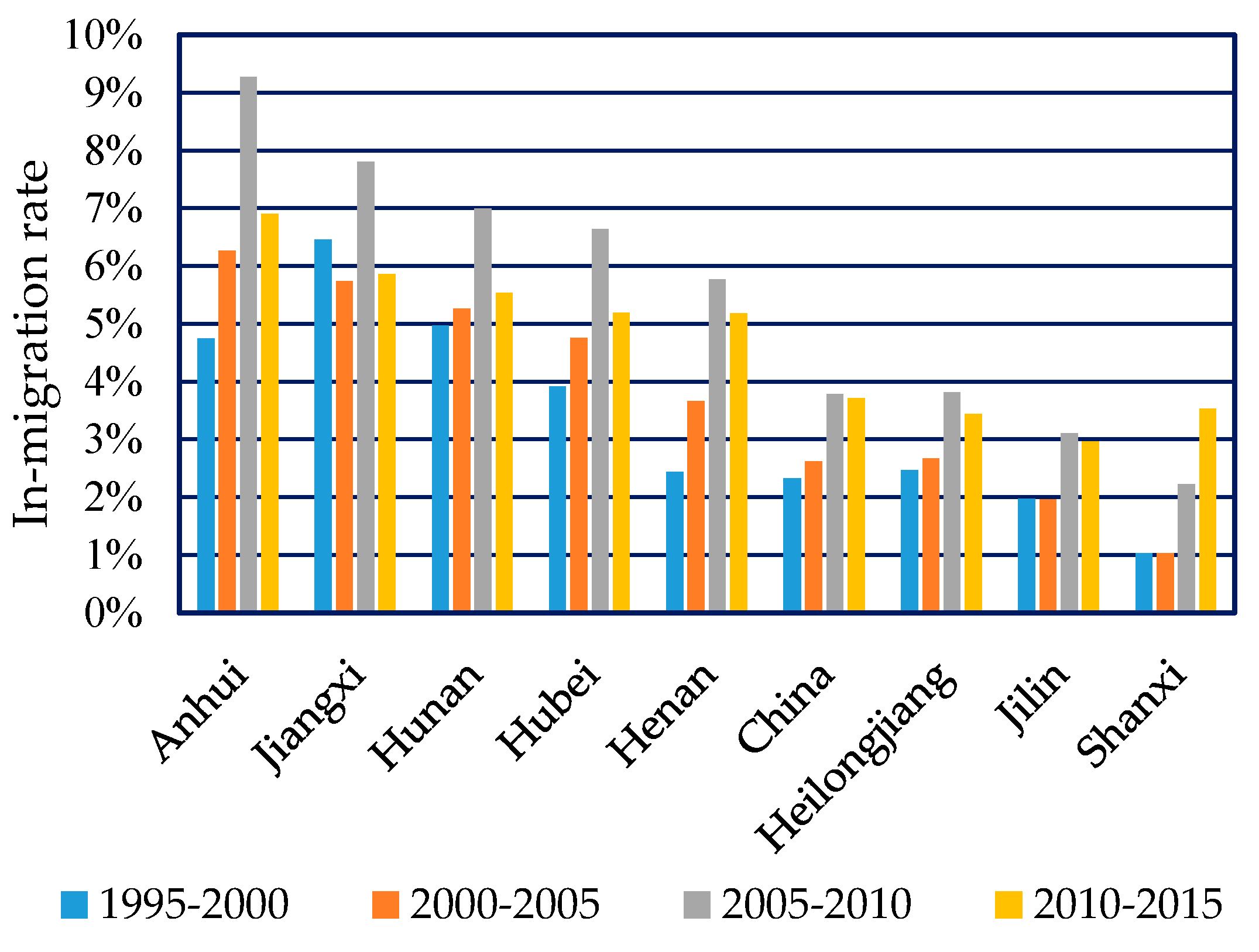

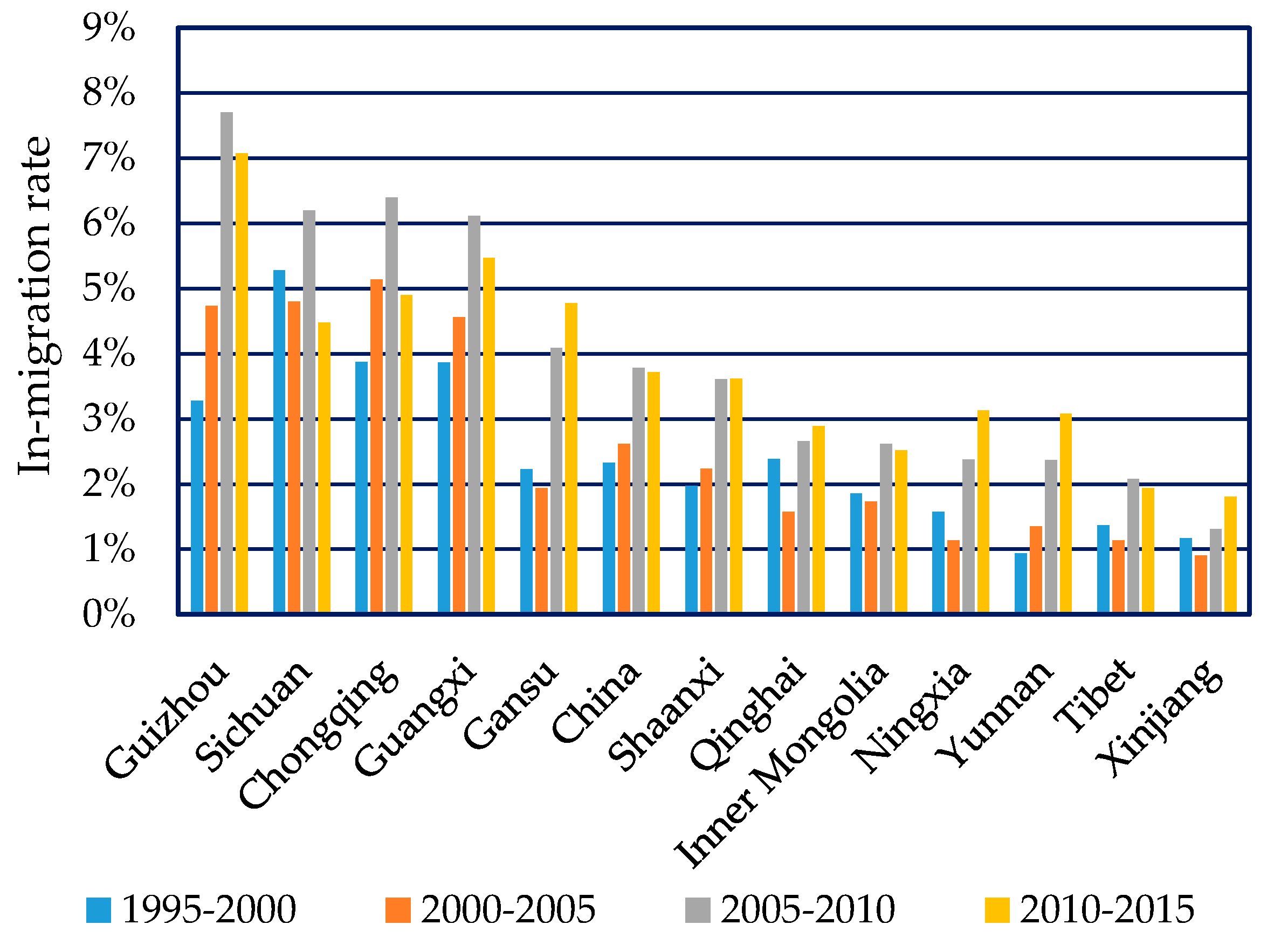

4.2. Regional Patterns and Dynamics of Inter-Provincial Migration Intensity

4.3. Regional Patterns and Dynamics of Inter-Provincial Migration Flow

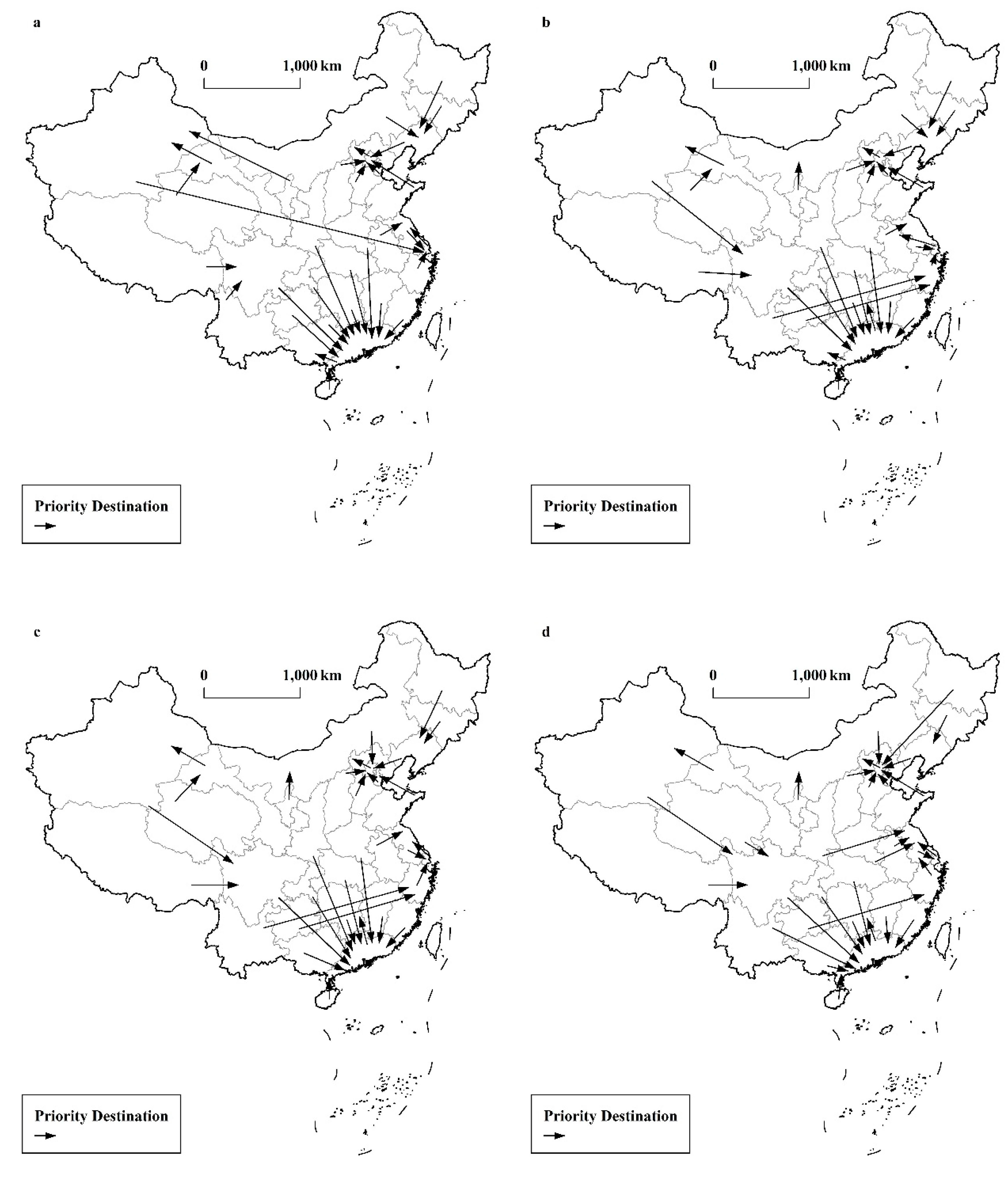

4.3.1. The Largest Inter-Provincial Migration Flows

4.3.2. The Largest Out-Migration Flows and In-Migration Flows of Each Province

4.4. Identifying the Main Factors of Migration from 1995–2000, 2000–2005, 2005–2010, and 2010–2015

4.4.1. Determinant Variables

4.4.2. Estimated Results in 1995–2000, 2000–2005, 2005–2010 and 2010–2015

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- He, S.; Bayrak, M.M.; Lin, H. A comparative analysis of multi-scalar regional inequality in China. Geoforum 2017, 78, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, C.C. Interprovincial migration, population redistribution, and regional development in China: 1990 and 2000 census comparisons. Prof. Geogr. 2005, 57, 295–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, C.C. Migration in a socialist transitional economy: Heterogeneity, socioeconomic and spatial characteristics of migrants in China and Guangdong province. Int. Migr. Rev. 1999, 33, 954–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, C.C. Modeling interprovincial migration in China, 1985–2000. Eurasian Geogr. Econ. 2005, 46, 165–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J. Changing Patterns and Determinants of Interprovincial Migration in China 1985–2000. Popul. Space Place. 2012, 18, 384–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J. Explaining Interregional Migration Changes in China, 1985–2000, Using a Decomposition Approach. Int. Migr. Rev. 2013, 49, 1176–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J. Increasing internal migration in China from 1985 to 2005: Institutional versus economic drivers. Habitat Int. 2013, 39, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, H.; Tang, Q.; Lu, D.; Xiao, N. Spatial-temporal patterns of China’s interprovincial migration, 1985–2010. J. Geogr. Sci. 2014, 24, 907–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Stillwell, J.; Shen, J.; Daras, K. Interprovincial Migration, Regional Development and State Policy in China, 1985–2010. Appl. Spat. Anal. Policy 2014, 7, 47–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G. The regional model of inter-provincial migration and its changes since China’s economic reform. Popul. Econ. 2000, 21, 8–16. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, G.; Pan, Z.; Lu, Y. China’s inter-provincial migration patterns and influential factors: Evidence from year 2000 and 2010 population census of China. Chin. J. Popul. Sci. 2012, 5, 2–13. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, T.; Qi, Y.; Cao, G.; Liu, H. Spatial patterns, driving forces, and urbanization effects of China’s internal migration: County-level analysis based on the 2000 and 2010 censuses. J. Geogr. Sci. 2015, 25, 236–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, X.; Liu, Y. Elderly Migration in China: Types, Patterns, and Determinants. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2017, 36, 751–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, C.; Gober, P. Gendering interprovincial migration in China. Int. Migr. Rev. 2003, 37, 1220–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Shen, J.F. Spatial patterns and determinants of skilled internal migration in China, 2000–2005. Pap. Reg. Sci. 2014, 93, 749–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Chen, W.Z. The Settlement Intention of China’s Floating Population in the Cities: Recent Changes and Multifaceted Individual-Level Determinants. Popul. Space Place 2010, 16, 253–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zipf, G.K. The PJVD Hypothesis: On the Intercity Movement of Persons. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1946, 11, 677–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fik, T.J.; Mulligan, G.F. Functional Form and Spatial Interaction Models. Environ. Plan. A Econ. Space 1998, 30, 1497–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyle, P.J.; Halfacree, K.H. Service Class Migration in England and Wales, 1980–1981: Identifying Gender-Specific Mobility Patterns. Reg. Stud. 1995, 29, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amara, M.; Jemmali, H. Deciphering the Relationship Between Internal Migration and Regional Disparities in Tunisia. Soc. Indic. Res. 2016, 135, 313–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J. Modelling Interregional Migration in China in 2005–2010: The Roles of Regional Attributes and Spatial Interaction Effects in Modelling Error. Popul. Space Place 2017, 23, e2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Ding, J.H.; Wang, G.X.; Shen, J.F.; Lin, L.Y.; Ke, W.Q. Population geography in China since the 1980s: Forging the links between population studies and human geography. J. Geogr. Sci. 2016, 26, 1133–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Shen, J.F. Jobs or Amenities? Location Choices of Interprovincial Skilled Migrants in China, 2000–2005. Popul. Space Place 2014, 20, 592–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Xu, W. Destination Choices of Permanent and Temporary Migrants in China, 1985-2005. Popul. Space Place 2017, 23, e1963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Service and Management of Migrant population National Health and Family Planing Commission of China. Report on China’s Migrant Population Development; China Population Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2016. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Qi, W.; Abel, G.J.; Muttarak, R.; Liu, S. Circular visualization of China’s internal migration flows 2010–2015. Environ. Plan. A 2017, 49, 2432–2436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, M.; Blake, M.; Boyle, P.; Duke-Williams, O.; Rees, P.; Stillwell, J.; Hugo, G. Cross-national comparison of internal migration: Issues and measures. J. R. Statist. Soc. 2002, 165, 435–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowry, I.S. Migration and Metropolitan Growth: Two Analytical Models; Chandler Pub. Co.: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, J. Modelling regional migration in China: Estimation and decomposition. Environ. Plan. A 1999, 31, 1223–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, J.M.C.S.; Tenreyro, S. The Log of Gravity. Rev. Econ. Stat. 2006, 88, 641–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, S.; Li, G.; Zhang, H.; Jin, L.; Su, Y.; Wu, K. Identifying the determinants of housing prices in China using spatial regression and the geographical detector technique. Appl. Geogr. 2017, 79, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Liang, Q.; Liu, J. The Commuting Characteristics of Beijing Spillover Population. Urban Dev. Stud. 2016, 33, 119–124. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loughlin, P.H.; Pannell, C.W. Growing Economic Links and Regional Development in the Central Asian Republics and Xinjiang, China. Post-Sov. Geogr. Econ. 2001, 42, 469–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X. Regional variations and changes in industrial productivity in China, 1980–1995. Asian Geogr. 2001, 20, 53–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, M.P. Climate change, internal migration, and the future spatial distribution of population: A case study of New Zealand. Popul. Environ. 2017, 39, 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anh, L.T.; Hoang Vu, L.; Bonfoh, B.; Schelling, E. An analysis of interprovincial migration in Vietnam from 1989 to 2009. Glob. Health Action 2012, 5, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hummel, D. Inter-State Internal Migration: State-level Wellbeing as a Cause. J. Happiness Stud. 2015, 17, 2149–2165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gries, T.; Kraft, M.; Simon, M. Explaining inter-provincial migration in China. Pap. Reg. Sci. 2016, 95, 709–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazgi, B.; Dokmeci, V.; Koramaz, K.; Kiroglu, G. Impact of Characteristics of Origin and Destination Provinces on Migration: 1995–2000. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2013, 22, 1182–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S. Population Migration and Urbanization in China: A Comparative Analysis of the 1990 Population Census and the 1995 National One Percent Sample Population Survey. Int. Migr. Rev. 2004, 38, 655–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Gabriel, S.A. Labor migration, human capital agglomeration and regional development in China. Reg. Sci. Urban Econ. 2012, 42, 473–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Liu, H.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, J. The Spatio-Temporal Characteristics and Modeling Research of Inter-Provincial Migration in China. Sustainability 2018, 10, 618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stillwell, J.; Daras, K.; Bell, M.; Lomax, N. The IMAGE Studio: A Tool for Internal Migration Analysis and Modelling. Appl. Spat. Anal. Policy 2014, 7, 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z. Urban labour-force experience as a determinant of rural occupation change: Evidence from recent urban-rural return migration in China. Environ. Plan. A 2001, 33, 237–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, H.; Tang, Q. Analysis of Determinants on Chinas Interprovincial Migration during 1985–2005. Adv. Mater. Res. 2013, 869–870, 1096–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Description | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Mij | The number of migrants from Province i to Province j, person | NPC 2000, NPC 2010; |

| PSPSS 2005, PSPSS 2010; | ||

| Pi; Pj | Populations at origin and destination POPi and POPj, million | China Statistical Yearbook (CSY) |

| Dij | The Euclidean distance in km between the capital city of the two provinces i and j, km | Ministry of Natural Resources of the People’s Republic of China (MNRPRC) |

| Cij | The value is 1 when province i and province j are adjacent, and 0 otherwise | MNRPRC |

| AHSi | Average household size at origin, person | CSY |

| RURALIi | Per Capita Annual Net Income of Rural Households at origin, RMB per person | CSY |

| URBANIj | Per Capita Annual Disposable Income of Urban Households at destination, RMB per person | CSY |

| SFGj | Share of foreign direct investment (FDI) in GDP, % | China compendium of statistics 1949–2008 |

| Provincial statistical yearbook | ||

| ALPCi | Arable land per capita at origin, ha/person | CSY |

| SWRi | Share of wages and salaries in the per capita income of Rural Households at origin, % | CSY |

| TDIj | Temperature difference index (average temperature differences between January and July) °C | CSY |

| PDj | Population density at destination, person/km2 | CSY |

| TGDPj | Share of tertiary industrial added value in GDP at destination, % | CSY |

| GDPGj | Economic growth rate at destination, % | CSY |

| Variables | 1995–2000 | 2000–2005 | 2005–2010 | 2010–2015 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | t-Value | Parameter | t-Value | Parameter | t-Value | Parameter | t-Value | |

| Pi | 1.0434 ** | 11.11 | 1.1747 ** | 12.31 | 1.1888 ** | 12.94 | 1.0327 ** | 14.44 |

| Pj | 0.8143 ** | 9.09 | 0.8216 ** | 10.41 | 0.7459 ** | 9.57 | 0.7265 ** | 7.69 |

| Dij | −0.8063 ** | −6.20 | −0.8769 ** | −6.79 | −0.8552 ** | −7.02 | −0.8458 ** | −8.20 |

| Cij | 0.7514 ** | 3.86 | 0.4562 ** | 2.41 | 0.4455 ** | 2.05 | 0.3652 * | 1.91 |

| AHSi | −3.8553 ** | −3.81 | −3.5797 ** | −3.76 | −2.2735 ** | −2.76 | −1.0923 | −1.54 |

| RURALIi | −1.6937 ** | −5.70 | −2.1029 ** | −6.52 | −2.0418 ** | −6.18 | −1.7043 ** | −4.97 |

| URBANIj | 4.6924 ** | 13.73 | 4.2896 ** | 14.68 | 4.8946 ** | 15.54 | 3.8258 ** | 12.89 |

| SFGj | 0.4369 ** | 5.25 | 0.3948 ** | 5.04 | 0.2315 ** | 2.47 | 0.2495 ** | 2.48 |

| ALPCi | −0.5130 ** | −2.75 | −0.8719 ** | −4.18 | −0.3992 ** | −2.23 | −0.4352 ** | −2.93 |

| SWRi | −0.6126 ** | −2.81 | −0.8285 ** | −3.39 | −0.5528 ** | −2.21 | −0.7996 ** | −2.57 |

| TDIj | 0.7871 ** | 2.39 | −0.4678 ** | −2.11 | −0.9425 ** | −3.98 | −1.0327 ** | −4.87 |

| PDj | −0.5612 ** | −6.31 | −0.3727 ** | −5.19 | −0.3997 ** | −6.87 | −0.2623 ** | −4.93 |

| Constant | −21.3839 ** | −4.35 | −14.5976 ** | −3.18 | −21.5302 ** | −4.47 | −15.3710 ** | −3.41 |

| R2 | 0.8138 | 0.7997 | 0.7031 | 0.6356 | ||||

| Pseudo log-likelihood | −10,827,826 | −12,696,191 | −16,115,789 | −15,806,808 | ||||

| Variables | 2005–2010 | 2010–2015 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | t-Value | Parameter | t-Value | |

| Pi | 1.1967 ** | 13.11 | 1.0339 ** | 14.55 |

| Pj | 0.9169 ** | 7.51 | 0.9865 ** | 8.57 |

| Dij | −0.8625 ** | −7.18 | −0.8174 ** | −8.00 |

| Cij | 0.4504 ** | 2.16 | 0.3908 ** | 2.12 |

| AHSi | −2.3599 ** | −2.96 | −0.9948 | −1.42 |

| RURALIi | −2.0607 ** | −6.35 | −1.5985 ** | −4.64 |

| URBANIj | 4.2552 ** | 11.28 | 3.7064 ** | 10.24 |

| SFGj | 0.3826 ** | 3.64 | 0.2192 ** | 2.17 |

| ALPCi | −0.4136 ** | −2.35 | −0.4169 ** | −2.93 |

| SWRi | −0.5547 ** | −2.23 | −0.7673 ** | −2.56 |

| TDIj | −0.7829 ** | −3.47 | −0.8348 ** | −4.03 |

| PDj | −0.4706 ** | −6.17 | −0.3180 ** | −5.44 |

| TGDPj | 0.9978 ** | 2.2 | 1.5783 ** | 3.58 |

| GDPGj | −1.0532 | −1.23 | 2.6790 ** | 3.01 |

| Constant | −9.5936 | −1.45 | −30.5830 ** | −3.69 |

| R2 | 0.7271 | 0.6573 | ||

| Pseudo log-likelihood | −15,722,443 | −15,109,954 | ||

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wu, R.; Yang, D.; Zhang, L.; Huo, J. Spatio-Temporal Patterns and Determinants of Inter-Provincial Migration in China 1995–2015. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3899. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10113899

Wu R, Yang D, Zhang L, Huo J. Spatio-Temporal Patterns and Determinants of Inter-Provincial Migration in China 1995–2015. Sustainability. 2018; 10(11):3899. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10113899

Chicago/Turabian StyleWu, Rongwei, Degang Yang, Lu Zhang, and Jinwei Huo. 2018. "Spatio-Temporal Patterns and Determinants of Inter-Provincial Migration in China 1995–2015" Sustainability 10, no. 11: 3899. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10113899

APA StyleWu, R., Yang, D., Zhang, L., & Huo, J. (2018). Spatio-Temporal Patterns and Determinants of Inter-Provincial Migration in China 1995–2015. Sustainability, 10(11), 3899. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10113899