Abstract

In the second decade of the 21st century, in the developed countries of Central Europe, we can observe the transfer of free time to consumption, including the consumption of cultural services. This change, however, has led to some disturbances in the consumption of cultural services. Disturbances, which in particular relate to the sphere of needs, the sphere of the means of meeting needs and, finally, the sphere of consumer behaviour; for example, in relation to transport. In this article, most of the attention was devoted to the last category of disturbances (the sphere of consumer behaviour) and specifically concerned the culture service customers’ choice of means of transport to a specific cultural event. The research carried out by the authors shows that the most popular means of transport used on the way to a symphonic concert held in Katowice is still one’s own car. This applies to both residents of the city of Katowice, who could easily get to the concert using public transport (bus, tram) or on foot, as well as people from outside Katowice (who, as the research shows, very rarely use Katowice’s extensive rail network and well-developed intercity bus service). Thus, it has been proved that despite various legal regulations conducive to sustainable consumption, the majority of Polish consumers of cultural services in the analysed area of consumer behaviour do not follow this concept. The article opens with a review of the literature on free time and the sustainable consumption of cultural services. The next part of the study presents the results and conclusions of research conducted on a group of 515 consumers of philharmonic services. The last part of the article discusses the results obtained and indicates the existing management implications.

1. Introduction

In the second decade of the 21st century, in the developed countries of Central Europe (including Poland), we can observe a systematic shortening of working time and a reduction in the time spent on life’s basic needs, as a result of which the amount of free time is increasing [1]. According to Cieloch et al. [2] (p. 17), this time can be filled with activities deemed desirable and it is one of the main paths leading to self-discovery for contemporary man. It is a special resource that serves to meet self-fulfillment needs through activities such as: travel and sports, having a hobby, reading, meeting friends and family, performing religious practices, volunteer work, fulfilling creative passions or experiencing the presence of works of art, and listening to and performing music.

The transfer of free time to consumption, including the consumption of cultural services, is fostered both by the enrichment of society in developed countries, as well as the legal regulations introduced in them. An example of such regulations may be the trade ban covering two Sundays of each month that has been introduced in Poland, or the 500+ programme, by which families with children receive additional monthly funds from the state budget, which are spent, among other things, on meeting cultural needs. However, these changes have also led to some disturbances in the consumption of cultural services; disturbances which may particularly relate to:

- (i)

- The sphere of needs; balance in this sphere is disturbed when the needs felt by the consumer are not his own needs, but are artificially created by, for example, advertising and marketing specialists, or formed as a result of social comparisons (e.g., participation in contemporary music concerts only because friends or neighbours are participating) [3,4];

- (ii)

- The sphere of means to meet the needs; here, disturbances occur when the means of satisfying the needs do not really serve to satisfy them (e.g., instead of going out with family to the theatre or the cinema, we decide to watch another episode of the soap opera or reality show on TV). W. Muszyński [5] said that, in the 21st century, a significant part of free time is consumed by the use of the media (television, computers, Internet, mobile phones). These meet most of the cultural needs of society and provide the so-called passive rest, as a result of which the consumer may paradoxically say “I feel tired” instead of “I became tired”, which could be the effect of actively using the offer of cultural institutions;

- (iii)

- The sphere of consumer behavior; this imbalance arises when, from among several ways to meet the need, the consumer chooses those that pose a greater burden to the environment (for example, despite the fact that a short distance of two kilometres to the museum or philharmonic can be travelled on foot or using public transport—bus, tram, subway—the consumer decides to use his own diesel car). This seemingly insignificant choice of the means of transport implies, however, a decision on whether we are dealing with sustainable or unsustainable consumption [6,7].

In this study, most of the attention was devoted to the last category of disturbances (the sphere of consumer behaviour) and specifically focused on the choice of means of transport by the consumer of cultural services on the way to a specific cultural event.

In the debate on sustainable consumption, one of the basic problems is the lack of general agreement on the definition of sustainable consumption—it still has not been determined up to what level consumption remains balanced and at what point it becomes unsustainable [8,9]. There is still no agreement on strategies that would best shape sustainable consumption, especially with regard to the sphere of cultural services [10,11,12]. For example, there are still no unambiguous answers to the questions on whether to support cultural education more, raise environmental awareness, or develop new services in the cultural sector. Therefore, various authors suggest that sustainable consumption in the cultural sector should be treated as an umbrella term, which covers issues such as: human needs, justice, quality of life, resource efficiency, the minimisation of waste generation, thinking in terms of product life cycle lengths, consumer health and safety, consumer sovereignty, etc. [10,13].

This paper, however, uses the definition of sustainable consumption developed by H. Jastrzębska-Smolaga [14], a precursor of research on sustainable consumption in Poland, according to which the balanced consumption of cultural services means a process of using cultural services that meet one’s needs, resulting in a better quality of life, but under two simultaneously fulfilled conditions:

- (i)

- The achievement of these objectives will be accompanied by a simultaneous radical reduction in the use of natural resources and energy, the reduction of waste emissions and environmental pollution, and discontinuation of the use of toxic materials [15];

- (ii)

- Achievement of a better quality of life for present generations will not become a hindrance to satisfying the fulfilment of needs by future generations [14] (pp. 72–73).

By culture services, we mean the products of cultural entities being subject to exchange, which are characterised by immateriality, impermanence, and diversity [16,17].

The implementation of sustainable consumption in the sphere of culture therefore means that the consumers of cultural services take responsibility for making ethical purchases, using the cultural offer in such a way as to limit the negative impact of consumption on the environment [18] (p. 551), which, in turn, ensures a decent life for everyone, within the limits of the Earth’s resources [19,20]. In the sphere of culture, sustainable consumption can therefore consist of using the services of cultural institutions in such a way as to limit the negative impact on the environment. This may be manifested, for example, in more frequent use of public transportation on the way to a specific cultural event. Therefore, the main purpose of this article is to determine what percentage of consumers of culture services, attending a symphony, uses means of transport such as a city bus, tram, bike, or walking. Thanks to this, it will be possible to recognise whether the behaviour of the surveyed consumers of cultural services in Poland are in line with the concept of the sustainable consumption of cultural services.

2. Materials and Methods

The research conducted in Katowice (the capital of the Silesian Metropolis, the largest city in the Silesia region in Poland) was part of a project implemented by Medialab Katowice within the Shared Cities: Creative Momentum international platform. The project was co-funded by the European Union as part of the Creative Europe Programme (https://www.sharedcities.eu/).

The main aim of research conducted was to determine the means of transport used by participants in artistic events to reach the concert in Katowice. The following issues were addressed in detail:

- (i)

- means of transport used by the inhabitants of Katowice to reach cultural events organized by the philharmonic institutions in Katowice;

- (ii)

- means of transport used by the inhabitants of the Province of Silesia to reach cultural events organized by the philharmonic institutions in Katowice;

- (iii)

- means of transport used by people residing outside the Province of Silesia to reach cultural events organized by the philharmonic institutions in Katowice.

Due to the relatively high costs, as well as the long duration, of full study (in order to be able to obtain full information about the correlation between the place of residence of participants in artistic events and the means of transport to the philharmonic institution, the study should be conducted during the whole artistic season among all participants in the concerts), the method of incomplete numerical induction was used. This is an inductive inference, the premises of which do not exhaust the whole world of objects to which general law expressed in the conclusion of reasoning refers to. The premises are detailed sentences here, the conclusion is a general sentence, and each premise results logically from the conclusion. This is a method in which a general rule is derived from a limited number of details [21,22].

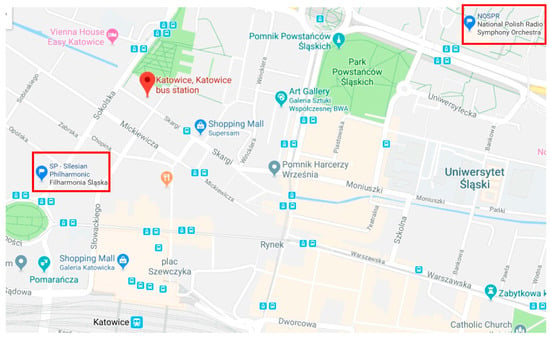

The respondents included the purchasers of cultural services provided by two philharmonic institutions in Katowice: the Polish National Radio Symphony Orchestra (NOSPR) in Katowice and Henryk Mikołaj Górecki Silesian Philharmonic in Katowice (SP). Both philharmonic institutions are located in the city centre of Katowice—there is a bus stop, as well as a tram stop, in their immediate vicinity. The distance between the two institutions from the main railway station and the main bus station does not exceed one kilometre (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Location of the NOSPR and SP concert hall in Katowice.

Quantitative research was conducted on the day of artistic events organized by the NOSPR and the SP immediately prior to their commencement. Information on the artistic events during which research was conducted is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Basic information on the artistic events during which research was conducted.

For research purposes, the mini-interview method was selected, and the research tool was comprised of interview guidelines and a registration sheet. The application of this method gives a much better chance that the respondent will be willing to provide information (compared to the survey method), especially nowadays, when similar questions (postal code collection) are widely used in large shopping centres.

Research was non-exhaustive—the sample size was 525 people. A total of 10 people were excluded from the sample because they gave the wrong postal code (the postal code given by seven people was not recognized in the postal code system of the Polish Post), and in addition, three people arrived at the NOSPR concert from outside Poland (two from Germany, one from Switzerland). As a result of the verification, a sample of 515 people was adopted.

Concert participants were asked to provide the postcode of their place of residence and the means of transport they used to come to the concert. The researchers entered the information collected manually into the registration sheet. The postal code, the means of transport, and the gender of the respondent were entered in the appropriate space. Research was conducted with the consent of the management of both philharmonic institutions (NOSPR and SP) in the place designated by the institution staff (an NOSPR hall and an SP hall and foyer). The most important information on the research is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Basic research assumptions.

The application of this method allowed for collecting detailed information about the territorial origin of the participants and how they reached the institution. An electronic database of postal codes of the Polish Post (kody.poczta-polska.pl) was used to compile the collected material. The postcode database allowed for a data set covering every postal area, municipality, county, and province of the place of residence of the participant to be obtained. The information obtained can be used, like geomarketing activities in commercial sectors, to develop the marketing communication strategy of philharmonic institutions and build their brand. It may also be useful for the local government of Katowice to build the image of the city, or to determine the city’s status or its metropolitan level.

3. Results

Moving on to the main part of the analysis, it should be noted that the results of the research, due to the sampling method used, provide knowledge about the respondents’ opinions concerning the behaviour of consumers in the market of cultural services in Poland, and not the actual state in this regard. However, we should take into account the large size of the research sample, as well as the integrity and good will of the respondents.

The sample consisted of 277 women (53.79%) and 238 men (46.21%). These were people living in 13 provinces. The respondents residing in the Province of Silesia represented all 19 Silesian cities with the county rights, as well as 15 out of 17 counties in the Province of Silesia. The largest group of respondents (453) was people living in the Province of Silesia—87.96% of all respondents. The remaining respondents (62 people, 12.04%) gave the postcode of their place of residence outside the Province of Silesia. Every fourth person visiting the Katowice’s philharmonic institution was an inhabitant of Katowice (129 people, 25.05%).

Participants in artistic events organized at the Polish National Radio Symphony Orchestra in Katowice and the Henryk Mikołaj Górecki Silesian Philharmonic were asked about the main means of transport they used to come to the concert. Respondents pointed to the means of transport, such as bus, TAXI, tram, coach, car, and train; some also came to the concert on foot. One person—a Swiss citizen—arrived at the NOSPR concert by plane. None of the respondents pointed to the bicycle as the main means of transport that they used to come to the concert. The research results are summarized in Table 3, Table 4, Table 5 and Table 6.

Table 3.

Means of transport used to reach Katowice’s philharmonic institutions (N = 515).

Table 4.

Means of transport used by visitors to the NOSPR.

Table 5.

Means of transport used by visitors to the Silesian Philharmonic (SP).

Table 6.

Means of transport used by visitors to the NOSPR and SP broken down by gender.

The data presented in Table 3 indicates that the car is the means of transport dominating among the inhabitants of Katowice and the inhabitants of the Province of Silesia, and among all the people reaching Katowice’s philharmonic institutions. Differences appear in the subsequent positions. For obvious reasons, the inhabitants of Katowice come on foot—every fifth inhabitant of Katowice (20.93%). Most often, the inhabitants of Katowice use public transport (bus and tram)—21.71%. Table 4 presents the means of transport used by the participants of the concert of the Polish National Radio Symphony Orchestra in Katowice.

The data presented in Table 4 shows that half of the participants of the NOSPR concert came to the concert on foot (nearly 33%) or by public transport (bus—12.50%, tram—4.69%). Other people used the car (48.44%) or taxis (1.56%). The inhabitants of the Province of Silesia definitely preferred the car (79.41%) as the main means of transport for travelling to the concert. This is probably related to the availability of many free parking spaces in the immediate vicinity of the NOSPR building. Table 5 presents the means of transport used by the participants of the concert in the Silesian Philharmonic in Katowice.

The data presented in Table 5 proves the previous findings that the car is the means of transport most often used by people coming to the concert in Katowice. Every fifth inhabitant of Katowice surveyed came to the Friday concert by bus—this might be due to the fact that a public transport stop is exactly opposite the main entrance to the Silesian Philharmonic.

Table 6 shows which means of transport are used by the surveyed consumers of NOSPR’s and SP’s cultural services on the way to the concert, broken down by the gender of the respondents.

The data presented in Table 6 shows that over 75% of all respondents come to the concerts in Katowice’s philharmonic institutions, the NOSPR and the SP, by car. The data also show that there are no significant differences between the surveyed men and women regarding the choice of means of transport on the way to a symphony concert. The most frequently chosen means of transport by both men and women was their own car.

4. Discussion

The research shows that the most popular means of transport used on the way to a symphonic concert held in Katowice is one’s own car [23]. This applies to both residents of the city of Katowice, who could easily get to the concert using public transport (bus, tram) or on foot, as well as people from outside Katowice (who, as the research shows, very rarely use Katowice’s extensive rail network and well-developed intercity bus service). Considering the fact that the majority of music lovers still come to a symphony concert by their own car (over 75%), as well as the fact that the vast majority of cars in Poland are petrol or diesel cars and the average age of a passenger car in Poland in 2016 was 15 [24], it is difficult to agree with the statement that the surveyed consumers of the services of philharmonic institutions in Katowice act in accordance with the concept of sustainable consumption (at least in the analysed area of consumer behaviour). This is also confirmed by other surveys conducted by the authors based on a sample of 2599 consumers of cultural services in Katowice in 2017 [25]. The research was conducted both in cultural institutions (National Polish Radio Symphony Orchestra in Katowice, Silesian Theatre, Silesian Museum, “Szyb Wilson” Art Gallery and “Silesia Film” Institution), as well as during numerous festivals and events organised in Katowice (Intel Extreme Masters, Interpretacje, JazzArt Festival, Regiofun, Silesia Bazaar, Silesian Jazz Festival and Tauron Nowa Muzyka)—Table 7.

Table 7.

How the respondents travel to an event organised by a cultural institution (in %).

Therefore, one should consider what solutions can be put in place to improve the current situation, so that the consumption of cultural services in Poland becomes more balanced (at least in the sphere of consumer behaviour). According to G. Ritzer [26,27], a change in the behaviour of consumers, including consumers of cultural services (the shift towards sustainable consumption), will not be possible without the introduction of systemic changes. He believes that it is not realistic for consumers to solve the problem of unsustainable consumption by only changing their individual behaviours. In order to create patterns of the sustainable consumption of cultural services at the individual level, it will be important to counterbalance negative trends related to consumption through appropriate systemic solutions (for example, some Polish cities are introducing free public transport to cultural institutions, other cities have banned diesel cars, and cultural education or education about sustainable energy management has been introduced in schools). Similarly, E. Assadourian [28] (pp. 113–124) claims that even those consumers of cultural services who introduce restrictions in their lives (i.e., for example, give up going to a concert at the Philharmonic in their own car in favour of public transport) are not able to carry out deeper changes when acting alone [29]. The only way to create a truly sustainable civilisation is to transform social and cultural norms in such a way that sustainable consumption and a sustainable lifestyle will become popular, universal, and attractive to follow (as is the case in New York, for example, where manual workers, regular office workers, and managers of large corporations use the metro). Of key importance for the implementation of sustainable consumption, however, is the construction of its framework conditions. To this end, economic, legal, and awareness instruments are used, as well as the building of green infrastructure, etc. It should be remembered that consumers, despite the responsibility they must bear, paradoxically cannot be burdened with excessive responsibility [30,31].

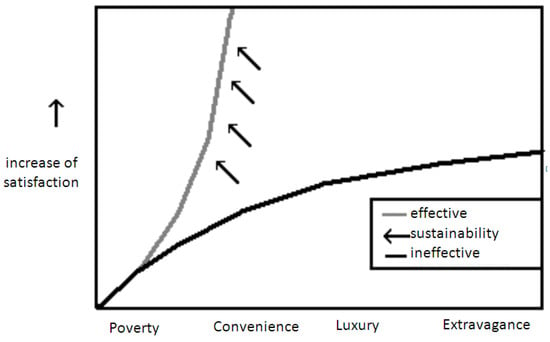

Making sustainable choices about the possible means of transport on the way to a symphony concert can be made easier using so-called choice editing, i.e., institutions and the local or federal government shape consumer choices. In shaping these choices in the area of transport, accessibility and mobility should be taken into account [32,33]. Accessibility means easy access to cultural goods and services, social facilities such as providing non-motorised forms of transport in urban areas (walking, cycling, roller-skating, etc.), and if necessary, providing motorised means of transport that are more efficient and create less pollution—in particular, the use of public transport, such as trams and electric buses. Mobility means maximising the sense of satisfaction per unit of mobility [34]. With the lowest possible level of mobility (meaning the actual level of consumption in the area of transport), an increase in satisfaction is desired (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Sustainable consumption in transport—increased satisfaction with a slight increase in mobility. Data source: Own work based on [34].

When writing about the sustainable consumption of cultural services, we should not, however, forget that it takes place in three key areas. In addition to the sphere of consumer behaviour, which was the subject of research by the original authors (in relation to transport), the sustainable consumption of cultural services should also be considered at the level of the sphere of needs and the sphere of the means of meeting needs. According to G. Ritzer [26,27], changing the behaviour of consumers of cultural services in the sphere of needs and in the sphere of the means of meeting needs will be much more difficult than in the sphere of consumer behaviour. Such a change is very difficult for at least two important reasons:

- (i)

- consumption in the sphere of culture is becoming less associated with the conscious purchase of culture services with a high level of artistic content, and is increasingly associated with entertainment and mass culture—the proportions in this area are becoming seriously disturbed. G. Ritzer [26,27] doubts that consumers will be willing to voluntarily give up the pleasures offered by entertainment for more difficult and more ambitious high culture;

- (ii)

- on the other hand, a significant number of consumers of culture services experience pleasure in consuming cultural services that provide a higher social status (Veblen’s theory of conspicuous consumption). The result is that in their choices, people often imitate the behaviour of a class which is at a level higher in the social stratification system. Veblen was of the opinion that people would endure even modest private lives, just to have public symbols that they deem desirable [26] (p. 312).

W. Muszyński [5] also draws attention to other disturbances in the sustainable consumption of cultural services. According to him, a significant part of leisure time that could be spent on the consumption of cultural services is, in the 21st century, consumed by the use of media (Internet, television, computers, mobile phones). This is also confirmed by research conducted by the Public Opinion Research Centre in Warsaw (CBOS) [1] and research in the Ariadna national panel conducted in February 2018 [35], which show that the most popular form of spending free time in Poland is browsing the Internet 75% and watching TV (nearly 66%). Only 9% of surveyed Poles said that they used the services of cultural institutions in their free time. According to Borys [32], in the second decade of the 21st century, there were many opportunities to meet cultural needs—however, these opportunities mean that it is easy to “become lost” and start meeting “not-one’s own” needs (i.e., it is very difficult to avoid unsustainable consumption patterns). Therefore, the sustainable consumption of cultural services is possible under the condition that every person conducts an “honest diagnosis of the state of their consciousness” [36] (p. 1) necessary to understand their own needs, both basic and imposed (external, constrained needs). In the opinion of Rogall [37], the cure for such a state of affairs should be working on one’s self-development and broadening one’s own perspective. Shaping rational thinking (so as not to be fooled by various temptations calling for unsustainable consumption) is an indispensable premise where, for example, in leisure time, a cultural offer that develops and enriches (satisfies the need for self-realisation) will be selected, and if a passive activity is selected (e.g., watching a film on TV), it will be a conscious choice.

In summary, it follows from the considerations that have been presented that the key issue for the implementation of the new paradigm of consumption in the cultural sector is the dissemination of a conscious and responsible consumer attitude. A conscious and responsible consumer who makes sustainable consumer choices is a person who realises the reasons for specific behaviours and their compliance with sustainable consumption patterns. Sustainable consumption in the cultural sector requires the introduction of sustainable management of the development of the cultural offer. Such a management model means, among other things, the development of public and alternative communication (walking, biking) instead of private (car) transportation [38] (p. 39). It also means the conscious and thoughtful selection of services from the rich cultural offer available on the market.

Author Contributions

L.W. and Z.D.-P. contributed equally to the development of the present paper, and all the phases have been discussed and worked by L.W. and Z.D.-P.

Funding

This research was funded by Medialab Katowice grant number KMO/17/03/D/13. The research was part of a project implemented by Medialab Katowice within the Shared Cities: Creative Momentum international platform.

Acknowledgments

Data collected by Medialab Katowice interviewers have been made available to the article’s authors for further in-depth analysis. Research was conducted in Katowice from 18 October 2016 to 17 July 2017 as part of a project implemented by Medialab Katowice within the Shared Cities: Creative Momentum international platform. The project was co-funded by the European Union as part of the Creative Europe Programme.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Free Time of Poles; Public Opinion Research Centre in Warsaw (CBOS): Warsaw, Poland, 2010.

- Cieloch, G.; Kuczyński, J.; Rogoziński, K. Czas Wolny—Czasem Konsumpcji? Państwowe Wydawnictwo Ekonomiczne: Warsaw, Poland, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Wróblewski, Ł. Cultural Management. Strategy and Marketing Aspects; Logos Verlag: Berlin, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sobocińska, M. Uwarunkowania i Perspektywy Rozwoju Orientacji Rynkowej w Podmiotach Sfery Kultury; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Ekonomicznego we Wrocławiu: Wrocław, Poland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Muszyński, W. Nowy Wspaniały Świat? Moda, Konsumpcja i Rozrywka Jako Nowe Style Życia; Wydawnictwo Adam Marszałek: Toruń, Poland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Voinea, L.; Filip, A. Analyzing the main changes in new consumer buying behavior during economic crisis. Int. J. Econ. Pract. Theor. 2011, 1, 14–19. [Google Scholar]

- Paluch, Ł.; Sroka, W. Socio-economic and environmental determinants of suistainable development of rural communes in małopolska province. Acta Sci. Pol. Oecon. 2013, 12, 65–76. [Google Scholar]

- Defila, R.; Di Giulio, A.; Kaufmann-Hayoz, R. Sustainable Consumption—An UnwieldyObject of Research. GAIA 2014, 23, 148–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edbring, E.G.; Lehner, M.; Mont, O. Exploring consumer attitudes to alternative models of consumption: Motivations and barriers. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 123, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mont, O.; Plepys, A. Sustainable consumption progress: Should we be proud or alarmed? J. Clean. Prod. 2008, 16, 531–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schor, J.B.; Craig, J.; Thompson, E. Sustainable Lifestyles and the Quest for Plenitude: Case Studies of the New Economy; Yale University Press: Yale, CT, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, D. Consuming conventions: Sustainable consumption, ecological citizenship and the worlds of worth. J. Rural Stud. 2011, 27, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, M.C. The Logic of Collective Action: Public Goods and the Theory of Groups; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Jastrzębska-Smolaga, H. W Kierunku Trwałej Konsumpcji. Dylematy, Zagrożenia, Szanse; Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN: Warsaw, Poland, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Vringer, K.; Heijden, E.; Soest, D.; Vollebergh, H.; Dietz, F. Sustainable Consumption Dilemmas. Sustainability 2017, 9, 942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wróblewski, Ł. Application of marketing in cultural organizations: The case of the Polish Cultural and Educational Union in the Czech Republic. Cult. Manag. Sci. Educ. 2017, 1, 79–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolb, B.M. Marketing for Cultural Organisations: New Strategies for Attracting Audiences to Classical Music, Dance, Museums, Theatre & Opera; Thomson Learning: Cork, Ireland, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, D. Thrifty, green or frugal: Reflections on sustainable consumption in a changing economic climate. Geoforum 2011, 42, 550–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorek, S.; Spangenberg, J.H. Sustainable consumption within a sustainable economy-beyond green growth and green economies. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 63, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, S.; Oates, C.J.; Alevizou, P.J.; Young, C.W.; Hwang, K. Individual strategies for sustainable consumption. J. Mark. Manag. 2012, 28, 445–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisiński, M. Structural Analysis of the Management Science Methodology. Bus. Manag. Educ. 2013, 11, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biesta, G. Pragmatism and the Philosophical Foundations of Mixed Methods Research. In SAGE Handbook of Mixed Methods in Social & Behavioral Research; Tashakkori, A., Teddlie, C., Eds.; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Dacko-Pikiewicz, Z.; Wróblewski, Ł. Spatial range of the influence of the philharmonic institutions in Katowice. Forum Sci. Oecon. 2017, 5, 17–34. [Google Scholar]

- Liczba Samochodów w Polsce, Europie i Na Świecie; Newsweek: Warsaw, Poland, 2018; Available online: https://www.newsweek.pl/styl-zycia/liczba-samochodow-w-polsce-europie-i-na-swiecie-statystyki/c6v0rwv (accessed on 10 October 2018).

- Wróblewski, Ł. Consumer behaviour in the market of cultural services. Am. J. Arts Manag. 2018, 1, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Ritzer, G. Magiczny Świat Konsumpcji; Warszawskie Wydawnictwo Literackie Muza S.A.: Warsaw, Poland, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ritzer, G. Makdonaldyzacja Społeczeństwa; Wydawnictwo Literackie Muza S.A.: Warsaw, Poland, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Assadourian, E.; Prugh, T. (Eds.) State of the World 2013. Is Sustainability Still Possible? Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2013; Available online: http://www.worldwatch.org/bookstore/publication/state-world-2013-sustainability-still-possible (accessed on 10 March 2018).

- Assadourian, E. The Path to Degrowth in Overdeveloped Countries. In State of the World 2012: Moving toward Sustainable Prosperity; Worldwatch Institute, Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2012; Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/283415624_The_Path_to_Degrowth_in_Overdeveloped_Countries (accessed on 10 October 2018).

- Akenji, L. Achieving absolute reductions in material throughput and energy use in society. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 65, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akenji, L.; Bengtsson, M. Making Sustainable Consumption and Production the Core of the Sustainable Development Goals; Institute for Global Environmental Strategies: Kanagawa, Japan, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Borys, T. Analiza Istniejących Danych Statystycznych Pod Kątem Ich Użyteczności Dla Określenia Poziomu Zrównoważonego Rozwoju Transportu Wraz z Propozycją Ich Rozszerzenia; Raport z realizacji Ekspertyzy; Ministerstwo Inwestycji i Rozwoju: Warsaw, Poland, 2008; Available online: http://www.mir.gov.pl/Transport/Zrownowazony_transport/Dokumenty_i_opracowania/Documents/Analiza_danych_statystycznych_zrownowazony_transport_2008.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2018).

- Holden, E. Achieving Sustainable Mobility; Ashgate Publishing Limited: Aldershot, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Litman, T. Measuring transportami on: Traffic, mobility and accessibility. ITE J. 2003, 73, 28–52. [Google Scholar]

- Uczestnictwo Polaków w Kulturze i Formy Spędzania Czasu Wolnego; Ariadna: Warsaw, Poland, 2018; Available online: http://ciekaweliczby.pl/zycie-kulturalne-sposoby-spedzania-czasu-wolnego-polakow/ (accessed on 10 October 2018).

- Borys, T. Zrównoważony rozwój i jakość życia człowieka czyli krótka historia o trzech drogach i postawach życiowych. Ekonatura 2011, 5, 28–30. [Google Scholar]

- Rogall, H. Ekonomia Zrównoważonego Rozwoju: Teoria i Praktyka; Wydawnictwo Zyski i S-ka: Poznań, Poland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Zaręba, D. Ekoturystyka; Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN: Warsaw, Poland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).