Financial Credit Risk Evaluation Based on Core Enterprise Supply Chains

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Definition of Supply Chain Finance

2.2. Credit Risk Evaluation of Supply Chain Finance

2.3. Risk Control for Supply Chain Finance

3. Theory of Supply Chain Financial Core Enterprise Risks

3.1. Credit Risk

3.2. Guarantee Risk

3.3. Operational Risk

4. Fuzzy Analytical Hierarchy Process (FAHP) Framework

4.1. Fuzzy Judgment Matrix

4.2. Fuzzy Judgment Matrix Consistency Check

4.3. Weight Vector of Criterion Layer B

4.4. Weight Vector of Index Layer C to Criterion Layer B

4.5. Composite Weight Vector

5. Empirical Analysis

5.1. Introduction to Core Enterprises

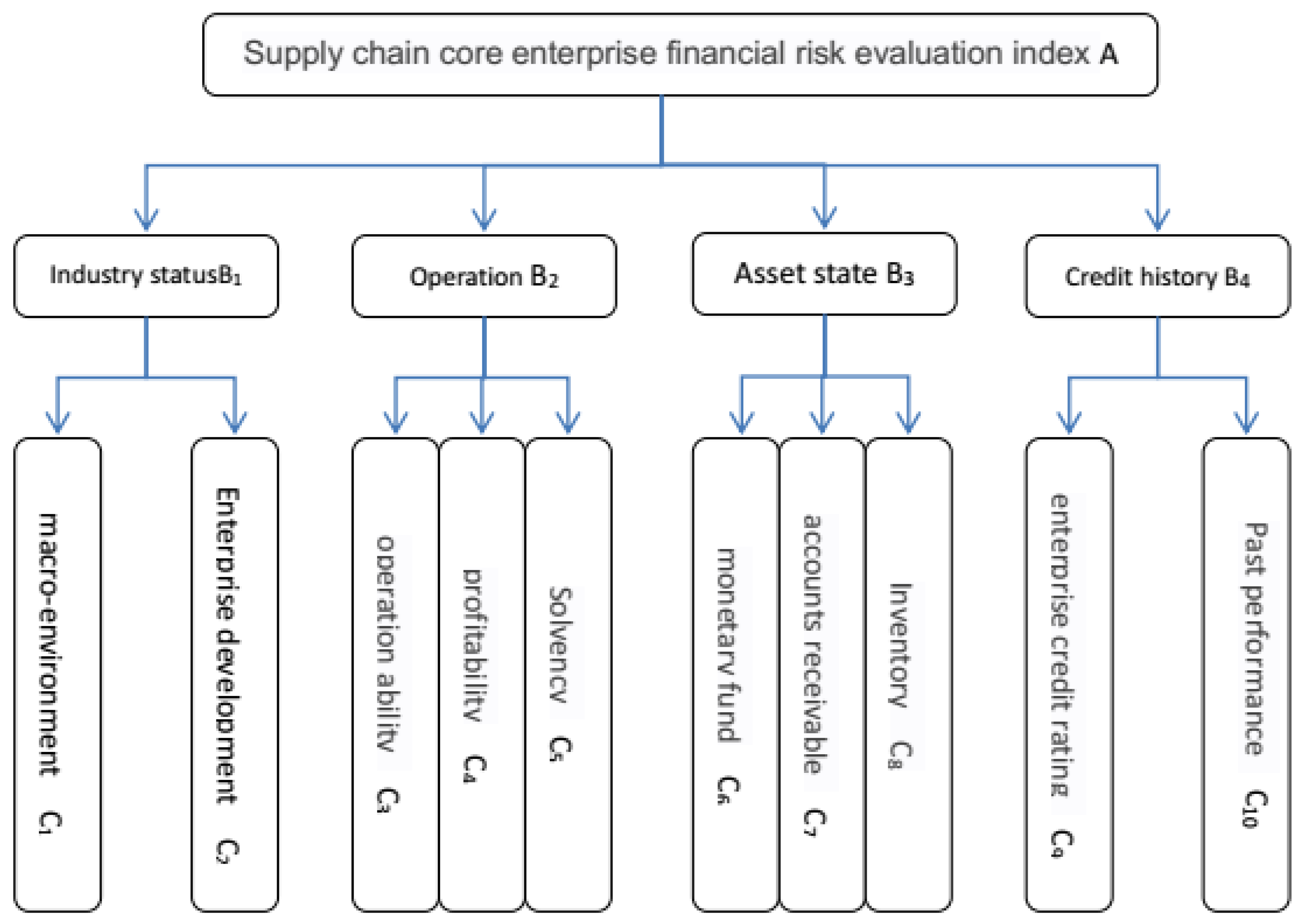

5.2. Evaluation System of the Core Enterprise Credit Risk

5.2.1. Core Enterprise Industry Status ()

5.2.2. Core Enterprise Operations ()

5.2.3. Asset Status of the Core Enterprises ()

5.2.4. Core Enterprise Credit History ()

5.3. Model Construction and Solution

6. Concluding Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Questionnaire

- Your gender is ( ).A. Male B. Female

- Your age is ( ).A. 20–30 years old B. 31–40 years old C. 41–50 years old D. 51–60 years old

- Your working life in this unit is ( ).A. 5 years or less B. 5–10 years C. 10–20 years D. 20 years or more

- Your position in this unit is ( ).A. General employees B. Middle-level employees C. Senior engineers D. Managers

- Your department in the unit is ( ).A. Purchasing department B. Production department C. Sales departmentD. Finance department E. Personnel Department F. Logistics Department G. Others

- The industry of the unit is ( ).A. Steel industry B. Textile industryC. Home appliance manufacturing D. Medical machinery industry

- Your academic qualifications ( ).A. High School B. Undergraduate C. Master/Dr. D. Specialist

| Risk factor | Risk level | ||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| Industry status | |||||

| Operation | |||||

| Asset state | |||||

| Credit history | |||||

| Risk factor | Risk level | ||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| Macro environment | |||||

| Enterprise development | |||||

| Operation ability | |||||

| Profitability | |||||

| Solvency | |||||

| Monetary fund | |||||

| Accounts receivable | |||||

| Inventory | |||||

| Enterprise credit rating | |||||

| Past performance | |||||

Appendix B. Calculation of the Fuzzy Judgment Matrices

References

- Berger, A.N.; Udell, G.F. A more complete conceptual framework for SME finance. J. Bank Financ. 2006, 30, 2945–2966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klapper, L. The role of factoring for financing small and medium enterprises. J. Bank Financ. 2006, 30, 3111–3130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, T.; Demirguc-Kunt, A. Small and medium-size enterprises: Access to finance as a growth constraint. J. Bank Financ. 2006, 30, 2931–2943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.L.; Guan, Z.G.; Xie, X. Risk evaluation model building of logistics financial business for the bank and empirical research. J. Syst. Manag. Sci. 2014, 4, 53–61. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, J.Z.; Guo, J.E.; Wang, S.B.; Wang, Z.H. Credit risk evaluation of online supply chain finance based on third-party B2B e-commerce platform: An exploratory research. International Journal of u- and e-Service. Sci. Technol. 2015, 8, 93–104. [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann, E. Supply chain finance: Some conceptual insights. Logistic Management. In Logistik Management—Innovative Logistikkonzepte; Lasch, R., Janker, C.G., Eds.; Deutscher Universitätsverlag: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Pfoh, H.; Gomm, M. Supply chain finance: Optimizing financial flows in supply chains. Logist. Res. 2009, 1, 149–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Dutta, K. Modeling of financial supply chain. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2011, 211, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathis, F.J.; Cavinato, J. Financing the global supply chain: Growing need for management action. Thunderbird Int. Bus. Rev. 2010, 52, 467–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvestro, R.; Lustrato, P. Integrating financial and physical supply chains: The role of banks in enabling supply chain integration. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2014, 34, 298–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackman, I.D.; Holland, C.P.; Westcott, T. Motorola’s global financial supply chain strategy. Supply Chain Manag. 2013, 18, 132–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caniato, F.; Gelsomino, L.M.; Perego, A.; Ronchi, S. Does finance solve the supply chain financing problem? Supply Chain Manag. 2016, 21, 534–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Xie, C.; Sun, B.; Wang, G.J.; Yan, X.G. Predicting China’s SME credit risk in supply chain financing by logistic regression, artificial neural network and hybrid models. Sustainability 2016, 8, 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhou, L.; Wu, Y.C.J. Supply chain finance in China: Business innovation and theory development. Sustainability 2015, 7, 14689–14709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldmann, M.; Müller, S. An incentive scheme for true information providing in Supply Chains. Omega 2003, 31, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, A.N.; Udell, G.F. The economics of small business finance: The roles of private equity and debt markets in the financial growth cycle. J. Bank Financ. 1998, 22, 613–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganlindo, A.; Schiantarelli, F. (Eds.) Credit Constraints and Investment in Latin America; Inter-American Development Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Schiffer, M.; Weder, B. Firm Size and the Business Environment: Worldwide Survey Results; Discussion Paper No. 43; International Finance Corporation: Washington, DC, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, T.; Demirguc-Kunt, A.; Laeven, L.; Maksimovic, V. The determinants of financing obstacles. J. Int. Money Financ. 2006, 25, 932–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Song, J.S.; Zipkin, P. Inventories with multiple supply sources and networks of queues with overflow bypasses. Manag. Sci. 2009, 55, 362–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wuttke, D.A.; Blome, C.; Henke, M. Focusing the financial flow of supply chains: An empirical investigation of financial supply chain management. Inter. J. Prod. Econ. 2013, 145, 773–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randall, W.S.; Farris, M.T. Supply chain financing: Using cash-to-cash variables to strengthen the supply chain. International Journal of Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2009, 39, 669–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Committee on Finance and Industry (1931), Report of Committee on Finance and Industry. Cmd 3897; p. 322. Available online: http://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/C1851842 (accessed on 20 September 2018).

- Stamp, J.C. The report of the Macmillan Committee. Econ. J. 1931, 41, 424–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.H.; Rhee, B.D. Trade credit for supply chain coordination. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2011, 214, 136–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jüttner, U.; Maklan, S. Supply chain resilience in the global financial crisis: An empirical study. Supply Chain Manag. 2011, 16, 246–259. [Google Scholar]

- Saaty, T.L. How to make a decision: The Analytic Hierarchy Process. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 1990, 48, 9–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Intensity of AHP Scale | Linguistic Variable | Positive Value | Positively Reciprocal Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Same importance | (1, 1, 1) | (1, 1, 1) |

| 3 | Weakly more important | (2, 3, 4) | (1/4, 1/3, 1/2) |

| 5 | Fairly more important | (4, 5, 6) | (1/6, 1/5, 1/4) |

| 7 | Strongly more important | (6, 7, 8) | (1/8, 1/7, 1/6) |

| 9 | Absolutely more important | (8, 9, 10) | (1/10, 1/9, 1/8) |

| 2, 4,6,8 | Intermediate values |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mou, W.; Wong, W.-K.; McAleer, M. Financial Credit Risk Evaluation Based on Core Enterprise Supply Chains. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3699. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10103699

Mou W, Wong W-K, McAleer M. Financial Credit Risk Evaluation Based on Core Enterprise Supply Chains. Sustainability. 2018; 10(10):3699. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10103699

Chicago/Turabian StyleMou, WeiMing, Wing-Keung Wong, and Michael McAleer. 2018. "Financial Credit Risk Evaluation Based on Core Enterprise Supply Chains" Sustainability 10, no. 10: 3699. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10103699

APA StyleMou, W., Wong, W.-K., & McAleer, M. (2018). Financial Credit Risk Evaluation Based on Core Enterprise Supply Chains. Sustainability, 10(10), 3699. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10103699