Impact of Information Intervention on the Recycling Behavior of Individuals with Different Value Orientations—An Experimental Study on Express Delivery Packaging Waste

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Research

2.1. Relevant Studies on the Impact of Information on Waste Recycling Behavior

2.2. Relevant Studies on the Structural Dimensions of Waste Recycling Behavior

2.3. Relevant Studies on Value Orientation and Its Influence on Individual Waste Recycling Behavior

3. Experimental Design and Implementation

3.1. Experimental Subjects and Tools

3.2. Design of Survey Scales and Information Intervention Materials

3.3. Experiment Implementation

3.3.1. Questionnaire Testing and Participant Selection and Grouping

3.3.2. Information Intervention and Process Control

3.3.3. Post Information Intervention Assessment

4. Data Analysis

4.1. Differential Analysis of Recycling Behavior among Individuals with Different Demographic Characteristics

4.2. Analysis of Recycling Behavior Changes Based on the Information Intervention Format

4.3. Analysis of Recycling Behavior Changes Based on Value Orientation

5. Discussion

5.1. Differences in Individual Demographic Characteristics of Participants and Their Express Packaging Waste Recycling Behavior

5.2. Effects of Different Forms of Information Intervention on Individual Recycling Behavior

5.3. Impact of Information Intervention on Individual Recycling Behavior of People with Different Value Orientations

5.4. Limitation

6. Conclusions and Suggestions

- (1)

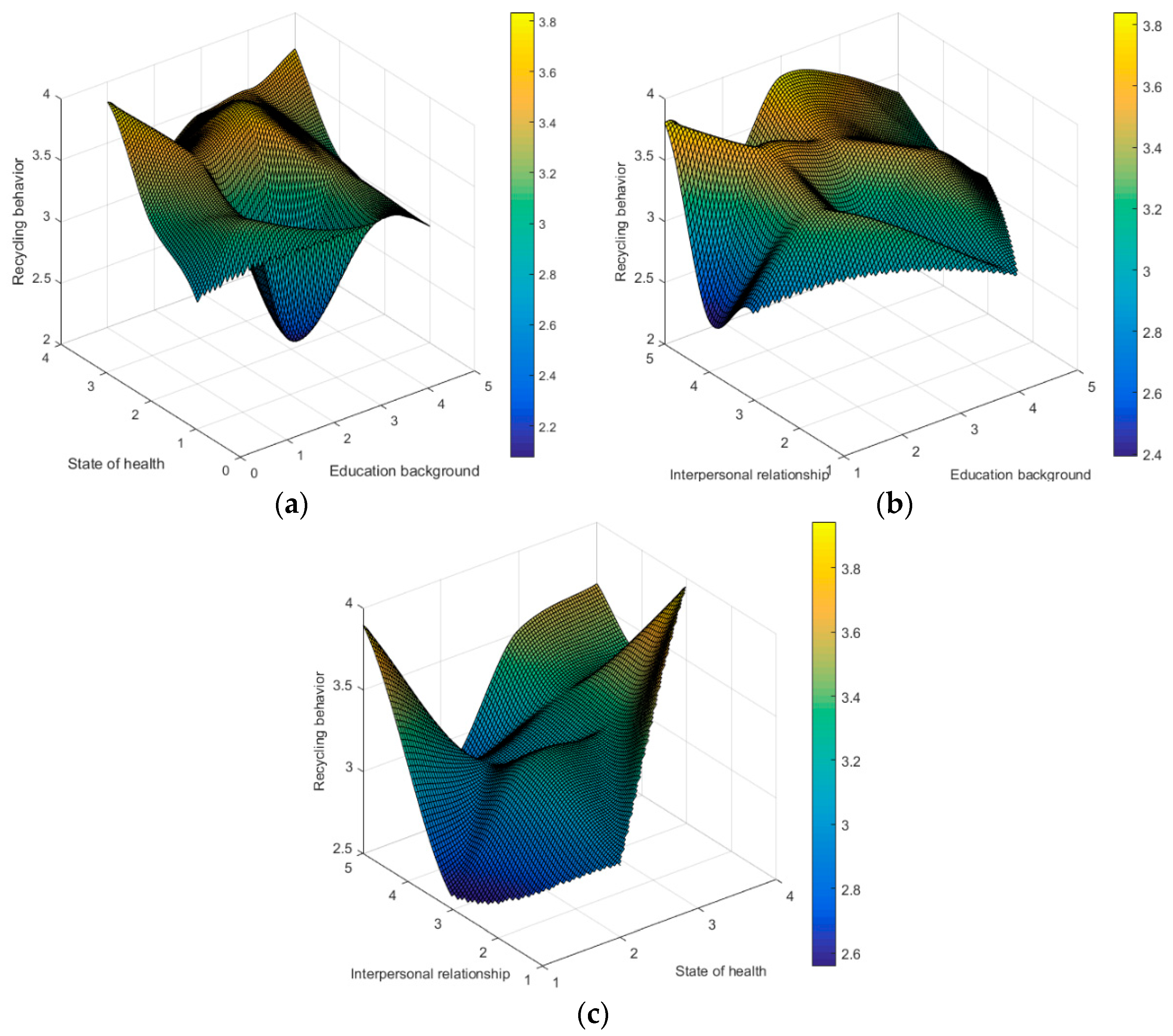

- Recycling behavior is significantly different due to an individual’s demographic characteristics. Specifically, the recycling behavior of individuals showed an “inverted U-shaped” change trend as their level of education increased. Individuals with junior college and bachelor-level university degrees are more active in sorting and recycling express packaging waste than are individuals with either less or more formal education. In addition, as their state of health and quality of interpersonal relationships improves, individuals were more willing to classify and recycle packaging waste as well as encourage others to do so. This finding indicated that individuals with poor health status and poor interpersonal relationships need more attention and intervention to promote their packaging waste recycling behavior.

- (2)

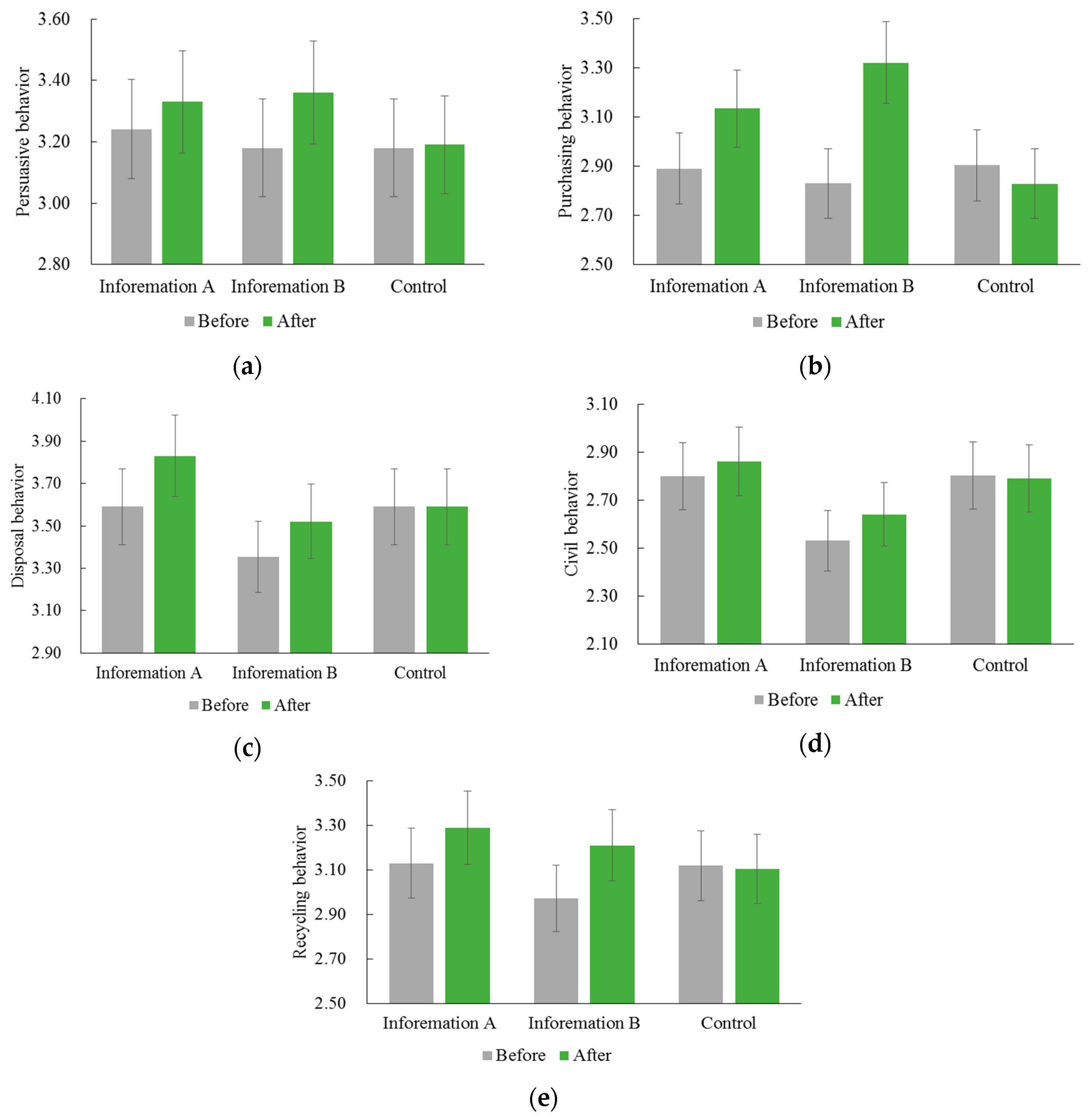

- Both text information and pictorial information significantly influenced the recycling behavior of participants. Although the scores for recycling behavior of individuals receiving picture information was higher than of those receiving text information, the difference was not statistically significant.

- (3)

- Interestingly, among the dimensions of recycling behavior, the scores for individual purchasing behavior were significantly increased after the pictorial information intervention and were significantly higher than the scores for participants receiving text information. In other words, information in the format of pictures can affect individuals’ purchasing behavior of express packaging more than text information.

- (4)

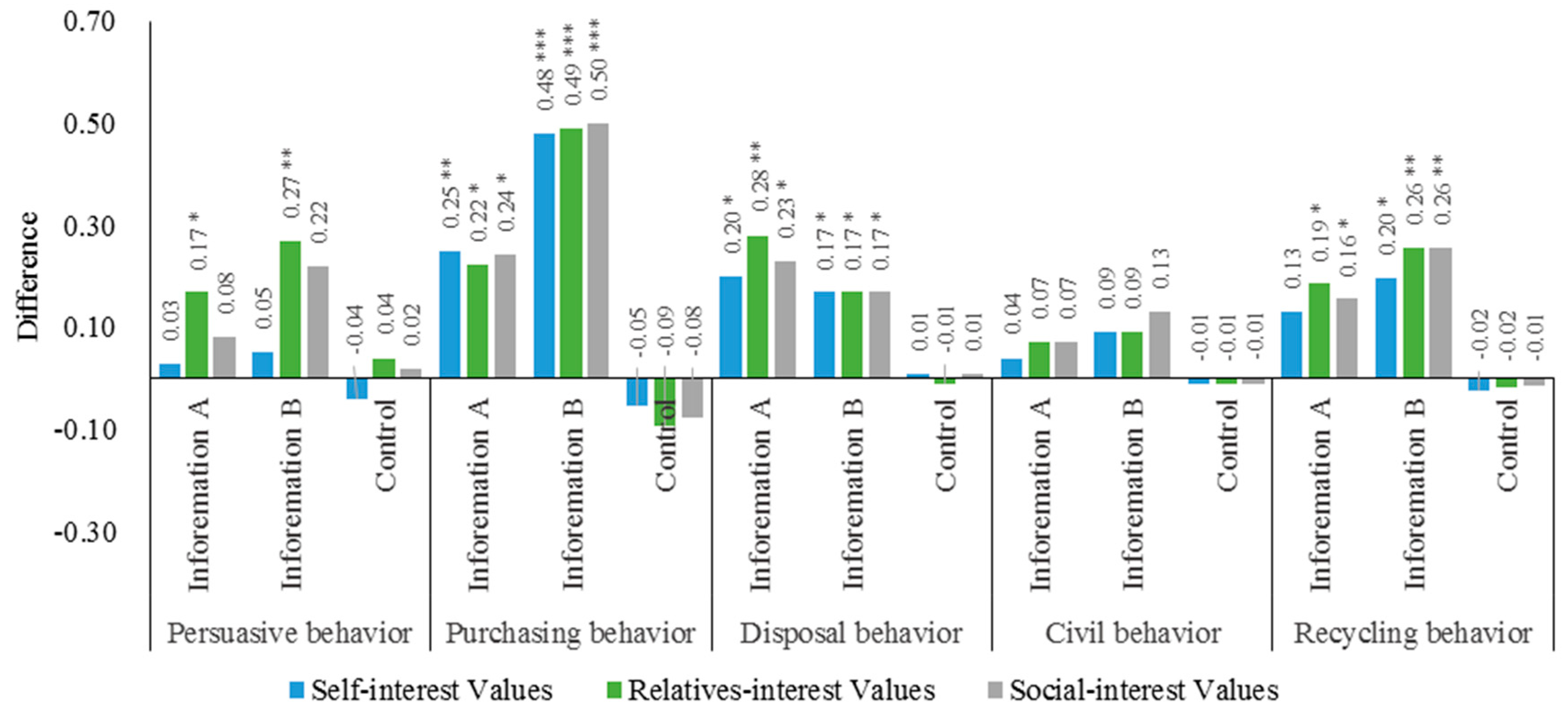

- Among different value orientation groups, text information cannot effectively change the overall recycling behavior of egocentric groups but can improve the overall recycling behavior of pro-relation groups and pro-social groups.

- (5)

- Notably, information intervention does not have an impact on individuals’ civil behavior, even on that of individuals with pro-social values, indicating the difficulty of awakening individual citizenship behavior by relying on information interventions.

- (1)

- A targeted guidance strategy based on individual’s demographic characteristics. The results showed that recycling behavior had a lower score in the groups with a junior high school education or below and master’s education or above, which were in a poor state of health and experienced poor interpersonal relationships. Therefore, the government needs to target and guide such “special” groups urgently. Specifically, the government can trigger individual recognition and attention to express packaging waste recycling by opening up socialized information dissemination channels and personalizing and customizing information dissemination and feedback. For example, establish individual classified information data and conduct targeted feedback in target groups through social networks (WeChat public platform, etc.) and, through the dynamic release of concern, increase the economic and health benefits from daily express packaging waste, and then improve recycling behavior.

- (2)

- A two-layer information interaction intervention strategy. The study concluded that due to the heterogeneity of individual value orientation, the degree of individual behavior change would differ according to the information of the intervention. This requires that the characteristics of individual psychological heterogeneity, especially the differences in value preference, must be taken into account in the content design and form selection of intervention information. Avoid the inhibition effect of the interaction between the situational information and the psychological information and induce the interaction promotion effect of the two-layer information. For example, in the induction of individual purchasing behavior, information in the form of pictures can be preferentially selected to stimulate and intervene in residents’ consumption. Through repeated information feedback and stimulation, individuals’ recycling behavior can be strengthened, and then the recycling behavior will be sustained and stable.

- (3)

- Endogenous environmental awareness actuation strategy. It is found that civil behavior cannot be effectively guided by simple information feedback. Driving the occurrence of civil behavior of express packaging waste needs to arouse citizens’ awareness of environmental protection, rights, and participation. In terms of policy intervention, it can start from the perspective of residents’ perception of psychological empowerment of express package waste recycling. Through specific information intervention measures, the residents’ perception of meaning, competence, choice, and the impact of express package waste recycling can be enhanced, and residents’ psychological empowerment experience can be increased, thus promoting their endogenous awareness of citizens and environmental protection.

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- State Post Bureau of People’s Republic of China (SPBPRC). The China’s Express Delivery Volume Will Reach 50 Billion in 2020. Available online: http://www.spb.gov.cn/ztgz/gjyzjzt/gwycwhy/xgbd/201512/t20151217_696037.html (accessed on 18 September 2018).

- Duan, H.; Li, J.; Liu, G. Developing countries: Growing threat of urban waste dumps. Nature 2017, 546, 599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrews, A.; Gregoire, M.; Rasmussen, H.; Witowich, G. Comparison of recycling outcomes in three types of recycling collection units. Waste Manag. 2013, 33, 530–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, F.; Chen, H.; Guo, D.; Han, S.; Long, R. How to achieve a cooperative mechanism of MSW source separation among individuals—An analysis based on evolutionary game theory. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 195, 521–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steg, L. Promoting household energy conservation. Energy Policy 2008, 36, 4449–4453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, J.; Long, R.; Chen, H. Impact of information intervention on travel mode choice of urban residents with different goal frames: A controlled trial in Xuzhou, China. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2016, 91, 134–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamberg, S.; Schmidt, P. Incentives, morality, or habit? Predicting students’ car use for university routes with the models of Ajzen, Schwartz, and Triandis. Environ. Behav. 2003, 35, 264–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Völlink, T.; Meertens, R. The effect of a prepayment meter on residential gas consumption. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2010, 40, 2556–2573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, R.A. Investigating the long-term impacts of climate change communications on individuals’ attitudes and behavior. Environ. Behav. 2014, 46, 70–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, W.; Russell, S.V.; Robinson, C.A.; Barkemeyer, R. Can social media be a tool for reducing consumers’ food waste? A behaviour change experiment by a UK retailer. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2016, 117, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marlow, N.; Jansson-Boyd, C.V. To touch or not to touch; that is the question. Should consumers always be encouraged to touch products, and does it always alter product perception. Psychol. Mark. 2011, 28, 256–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhu, Y. Effects of online pictorial versus verbal reviews of experience product on consumer’s judgment. Acta Psychol. Sin. 2016, 48, 1026–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prochaska, J.O.; Redding, C.A.; Evers, K.E. The transtheoretical model and stages of change. Health Behav. Health Educ. 2008, 22, 97–121. [Google Scholar]

- Locke, E. Motivation, cognition, and action: An analysis of studies of task goals and knowledge. Appl. Psychol. 2000, 49, 408–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courbalay, A.; Deroche, T.; Prigent, E.; Chalabaev, A.; Amorim, M.-A. Big Five personality traits contribute to prosocial responses to others’ pain. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 2015, 78, 94–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzoni, I.; Nicholson-Cole, S.; Whitmarsh, L. Barriers perceived to engaging with climate change among the UK public and their policy implications. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2007, 17, 445–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winett, R.A.; Leckliter, I.N.; Chinn, D.E.; Stahl, B.; Love, S.Q. Effects of television modeling on residential energy conservation. J. Appl. Behav. Anal. 2013, 18, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geller, E.S. Evaluating energy conservation programs: Is verbal report enough? J. Consum. Res. 1981, 8, 331–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMakin, A.H.; Malone, E.L.; Lundgren, R.E. Motivating residents to conserve energy without financial incentives. Environ. Behav. 2002, 34, 848–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staats, H.; Hartig, T. Alone or with a friend: A social context for psychological restoration and environmental preferences. J. Environ. Psychol. 2004, 24, 199–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Guo, D.; Wang, X.; Zhang, B.; Wang, B. How does information publicity influence residents’ behaviour intentions around e-waste recycling? Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 133, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sia, A.P.; Hungerford, H.R.; Tomera, A.N. Selected predictors of responsible environmental behavior: An analysis. J. Environ. Educ. 1986, 17, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thapa, B. The mediation effect of outdoor recreation participation on environmental attitude-behavior correspondence. J. Environ. Educ. 2010, 41, 133–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith-Sebasto, N.J.; D’Costa, A. Designing a Likert-type scale to predict environmentally responsible behavior in undergraduate students: A multistep process. J. Environ. Educ. 1995, 27, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.H.; Jan, F.H.; Yang, C.C. Conceptualizing and measuring environmentally responsible behaviors from the perspective of community-based tourists. Tour. Manag. 2013, 36, 454–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Chen, F.; Huang, X.; Long, R.; Li, W. Are individuals’ environmental behavior always consistent?—An analysis based on spatial difference. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 125, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristiansen, C.M.; Zanna, M.P. The rhetorical use of values to justify social and intergroup attitudes. J. Soc. Issues 1994, 50, 47–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freud, E.; Kidron, D.; Gornish, M.; Barak, R.; Golinski, D.; Zer, M. The value of precise preoperative localization of colonic arteriovenous malformation in childhood. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 1993, 88, 443–446. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fehr, E.; Fischbacher, U. The nature of human altruism. Nature 2003, 425, 785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, S.C.G.; Barton, M.A. Ecocentric and anthropocentric attitudes toward the environment. J. Environ. Psychol. 1994, 14, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H. Universals in the content and structure of values: Theoretical advances and empirical tests in 20 countries. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1992, 25, 1–65. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, S.H. Are there universal aspects in the structure and contents of human values? J. Soc. Issues 1994, 50, 19–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C.; Kalof, L.; Dietz, T.; Guagnano, G.A. Values, beliefs, and pro-environmental action: Attitude formation toward emergent attitude objects. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1995, 25, 1611–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C.; Dietz, T.; Guagnano, G.A. A brief inventory of values. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1998, 58, 984–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarty, J.A.; Shrum, L.J. The recycling of solid wastes: Personal values, value orientations, and attitudes about recycling as antecedents of recycling behavior. J. Bus. Res. 1994, 30, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barr, S. Strategies for sustainability: Citizens and responsible environmental behavior. Area 2003, 35, 227–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Chen, H.; Guo, D.; Long, R. Analysis of undesired environmental behavior among Chinese undergraduates. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 162, 1239–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H. Travelers’ pro-environmental behavior in a green lodging context: Converging value-belief-norm theory and the theory of planned behavior. Tour. Manag. 2015, 47, 164–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zou, Y.; Wu, J. Factors influencing public-sphere pro-environmental behavior among Mongolian college students: A test of value–belief–norm theory. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Chen, H.; Huang, X.; Long, R.; Lu, H.; Yue, T. Public response to the regulation policy of urban household waste: Evidence from a survey of Jiangsu Province in China. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiangsu Province Post Office (JPPO). Statistical Bulletin of the Development of Postal Industry in Jiangsu Province. Available online: http://js.spb.gov.cn/xytj/tjxx/ (accessed on 18 September 2018).

- Ministry of Industry and Information (MII). Available online: http://www.miit.gov.cn/n1146295/n1146592/n1146764/n6026279/index.html (accessed on 18 September 2018).

- Brazil, W.; Caulfield, B. Does green make a difference: The potential role of smartphone technology in transport behavior. Transp. Res. Part C 2013, 37, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J. Experimental Study on the Impact of Consumption Carbon Emission Reduction Policies; Sci. Press: Beijing, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Lu, X. Reform and innovation of graduate education mode in China. China High. Educ. Res. 2016, 20, 45–46. [Google Scholar]

- Gregorio, J.D.; Lee, J. Education and income inequality: New evidence from cross-country data. Rev. Income Wealth 2002, 48, 395–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Kahn, M.E.; Zheng, S. Self-protection investment exacerbates air pollution exposure inequality in urban China. Ecol. Econ. 2017, 131, 468–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W. Thoughts of promoting China’s express packaging legislation. Acad. J. Zhongzhou 2018, 3, 62–66. [Google Scholar]

- Ferris, G.R.; Rogers, L.M.; Blass, F.R.; Hochwarter, W.A. Interaction of job-limiting pain and political skill on job satisfaction and organizational citizenship behavior. J. Manag. Psychol. 2009, 24, 584–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wossink, G.A.A.; Wenum, J.H.V. Biodiversity conservation by farmers: Analysis of actual and contingent participation. Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2003, 30, 461–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peter, A.L.; Viraraghavan, T. Thallium: A review of public health and environmental concerns. Environ. Int. 2005, 31, 493–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooke, S.J.; Vermaire, J.C. Environmental studies and environmental science today: Inevitable mission creep and integration in action-oriented transdisciplinary areas of inquiry, training and practice. J. Environ. Stud. Sci. 2015, 5, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zhang, J.; Peracchio, L.A. Understanding the impact of self-concept on the stylistic properties of images. J. Consum. Psychol. 2010, 20, 508–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Childers, T.L. Memory for the visual and verbal components of print advertisements. Psychol. Mark. 2010, 3, 137–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, R.C.; Esther, T. The effects of progressive levels of interactivity and vividness in web marketing sites. J. Advert. 2001, 30, 65–77. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, F.; Xi, B.; Wang, L. Evolutionary game analysis of environmental regulation strategy between local governments. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2014, 24, 97–102. [Google Scholar]

- Abbey, B.S.; Doukas, J.A. Is technical analysis profitable for individual currency traders? J. Portf. Manag. 2012, 39, 142–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, S.M.; Tor, A.; Bazerman, M.H.; Miller, D.T. Profit maximization versus disadvantageous inequality: The impact of self-categorization. J. Behav. Decis. Mak. 2005, 18, 187–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Value Orientation | Waste Recycling Behavior | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Component | Component | |||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||

| Item 4 | 0.813 | 0.156 | 0.006 | Item 3 | 0.723 | 0.204 | 0.019 | 0.082 |

| Item 2 | 0.738 | 0.320 | 0.010 | Item 2 | 0.618 | 0.161 | 0.030 | 0.215 |

| Item 1 | 0.652 | 0.442 | 0.031 | Item 1 | 0.617 | 0.113 | 0.154 | 0.182 |

| Item 3 | 0.650 | 0.223 | 0.040 | Item 4 | 0.019 | 0.770 | 0.008 | 0.139 |

| Item 7 | 0.298 | 0.770 | 0.086 | Item 6 | 0.280 | 0.676 | 0.071 | 0.209 |

| Item 5 | 0.248 | 0.744 | 0.163 | Item 5 | 0.309 | 0.670 | 0.172 | 0.235 |

| Item 7 | 0.075 | 0.719 | 0.097 | Item 10 | 0.209 | 0.118 | 0.725 | 0.026 |

| Item 9 | 0.190 | 0.033 | 0.816 | Item 8 | 0.227 | 0.020 | 0.716 | 0.228 |

| Item 11 | 0.057 | 0.152 | 0.674 | Item 7 | 0.246 | 0.021 | 0.705 | 0.203 |

| Item 8 | 0.033 | 0.062 | 0.619 | Item 9 | 0.298 | 0.099 | 0.703 | 0.177 |

| Item 10 | 0.024 | 0.013 | 0.601 | Item 13 | 0.267 | 0.347 | 0.122 | 0.721 |

| Item 11 | 0.242 | 0.395 | 0.119 | 0.698 | ||||

| Item 12 | 0.156 | 0.101 | 0.112 | 0.675 | ||||

| Item 14 | 0.101 | 0.240 | 0.206 | 0.606 | ||||

| Social Demographic Variables | Recycling Behavior (M ± SD) | Persuasive Behavior (M ± SD) | Disposal Behavior (M ± SD) | Civil Behavior (M ± SD) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Education background | Junior high school or below | 3.03 ± 0.84 | 3.00 ± 0.90 | / | 2.58 ± 1.08 |

| Senior high school or technical secondary school | 3.34 ± 0.81 | 3.47 ± 0.81 | / | 2.63 ± 0.87 | |

| Junior college | 3.56 ± 0.92 | 3.55 ± 0.99 | / | 3.16 ± 1.20 | |

| Bachelor | 3.43 ± 0.76 | 3.59 ± 0.76 | / | 3.12 ± 0.96 | |

| Masters or above | 3.15 ± 0.79 | 3.29 ± 0.94 | / | 2.78 ± 0.88 | |

| F | 2.56 * | 2.60 * | / | 2.63 * | |

| State of health | Poor | 3.01 ± 0.95 | / | 3.25 ± 1.09 | / |

| Average | 3.09 ± 0.78 | / | 3.39 ± 0.78 | / | |

| Good | 3.34 ± 0.75 | / | 3.70 ± 0.72 | / | |

| Excellent | 3.54 ± 0.92 | / | 3.86 ± 1.00 | / | |

| F | 2.66 * | / | 2.88 * | / | |

| Interpersonal relationship | Poor | 2.94 ± 0.80 | 3.00 ± 0.86 | 3.57 ± 0.82 | / |

| Average | 3.26 ± 0.71 | 3.27 ± 0.77 | 3.61 ± 0.66 | / | |

| Good | 3.26 ± 0.74 | 3.40 ± 0.80 | 3.75 ± 0.77 | / | |

| Excellent | 3.57 ± 0.94 | 3.69 ± 0.98 | 3.96 ± 0.93 | / | |

| F | 2.68 * | 2.61 * | 3.79 ** | / | |

| Variable | Difference (2)–(1) | Difference (5)–(4) | Difference (8)–(7) | Difference (6)–(3) | Difference (9)–(3) | Difference (9)–(6) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (3) (p-value) | (6) (p-value) | (9) (p-value) | (10) (p-value) | (11) (p-value) | (12) (p-value) | |

| Persuasive behavior | +0.01 (0.704) | +0.09 (0.192) | +0.18 (0.033) | +0.08 (0.234) | +0.17 (0.038) | +0.09 (0.192) |

| Purchasing behavior | −0.08 (0.234) | +0.24 (0.010) | +0.49 (0.001) | +0.32 (0.002) | +0.57 (0.000) | +0.25 (0.005) |

| Disposal behavior | 0.00 (1.000) | +0.24 (0.010) | +0.17 (0.038) | +0.24 (0.010) | +0.17 (0.038) | −0.07 (0.296) |

| Civil behavior | −0.01 (0.704) | +0.06 (0.385) | +0.11 (0.146) | +0.07 (0.296) | +0.12 (0.102) | +0.05 (0.498) |

| Recycling behavior | −0.01 (0.704) | +0.16 (0.042) | +0.24 (0.010) | +0.17 (0.038) | +0.25 (0.005) | +0.08 (0.234) |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, F.; Chen, H.; Yang, J.; Long, R.; Li, Q. Impact of Information Intervention on the Recycling Behavior of Individuals with Different Value Orientations—An Experimental Study on Express Delivery Packaging Waste. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3617. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10103617

Chen F, Chen H, Yang J, Long R, Li Q. Impact of Information Intervention on the Recycling Behavior of Individuals with Different Value Orientations—An Experimental Study on Express Delivery Packaging Waste. Sustainability. 2018; 10(10):3617. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10103617

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Feiyu, Hong Chen, Jiahui Yang, Ruyin Long, and Qianwen Li. 2018. "Impact of Information Intervention on the Recycling Behavior of Individuals with Different Value Orientations—An Experimental Study on Express Delivery Packaging Waste" Sustainability 10, no. 10: 3617. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10103617