Taiwan Roadkill Observation Network: An Example of a Community of Practice Contributing to Taiwanese Environmental Literacy for Sustainability

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- (1)

- Whether TaiRON’s operational model is essentially consistent with the theory of community of practice, and

- (2)

- Whether, and to what extent, TaiRON has contributed to the dissemination of environmental knowledge among its volunteers and the general public.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Citizen Science

2.2. Community of Practice

- Domain: A domain of knowledge is a key component of a community of practice. Community members must discuss the core values of their community; such as issues of concern, organizational strategies, and the desired effect from community activities.

- Community: In pursuing a categorical interest, the development of the community must be focused, organized, and nurtured. For example, community members should follow the community’s guidelines, support the emotional development of community members, participate in the community’s activities, or seek to deploy an operational method in a community to maintain the community’s vitality and growth.

- Practice: To maintain its inclusion in the field of knowledge, the community must constantly participate in or develop various relevant activities. Activities can help the community to effectively acquire knowledge resources and inherit knowledge. Community members can learn from their practice.

- Humans are social—this is the core concept of this learning theory;

- Knowledge is valuable for work and other tasks and activities;

- People are motivated to seek knowledge to understand causes and participate in activities;

- Ultimate meaning—our experiences and actions are the final outcome of learning.

- Meaning: How we understand whether the actions we undertake are valuable within the larger context of our life and society.

- Practice: The sharing of history and social resources, structures, ideas, and the ability to continue participating in joint actions.

- Community: An organization or business should define its goals, and members should buy-in to those goals.

- Identity: Learning changes the individual, and we can examine how a personal history is created and altered in the context of a community.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Participation Observation

3.2. Content Analysis

3.3. Unstructured Interviews

4. Results

4.1. Analyzing TaiRON in Light of the Four Principles of Social Theory of Learning

4.2. Three Core Elements of Community of Practice Theory and TaiRON

“Participants can achieve a deeper level of communication when they engage in the citizen science recording project. Then, during the discussion concerning the dead animals by the roadside, if the participants share an opinion and we realize that is a good topic, we responded to the commenting member after the discussion. In so doing, we satisfy their desire to express their ideas and concepts.”(Mr. Lin, 26 March 2017)

4.3. Legitimate Peripheral Participation and TaiRON

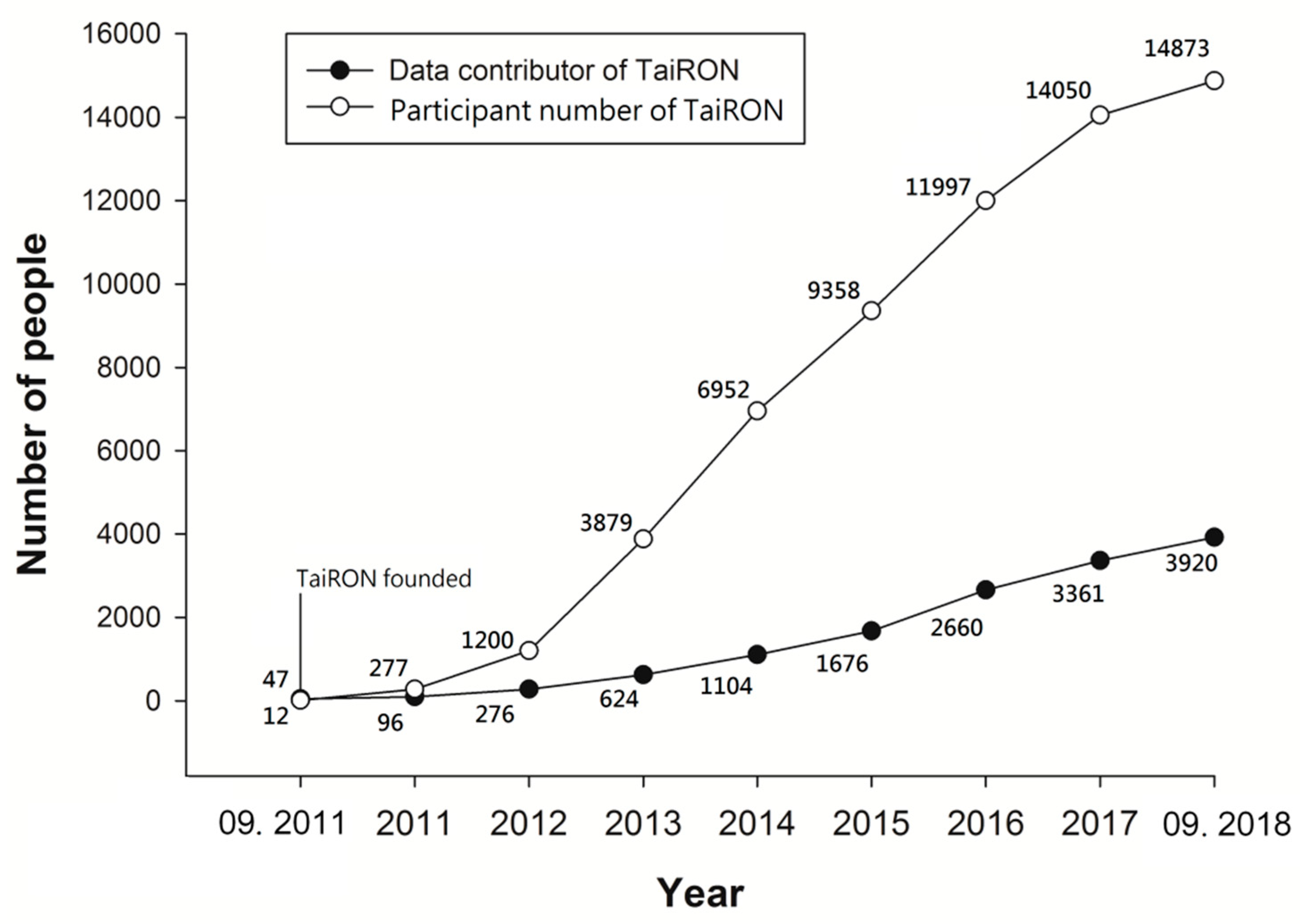

“Participants discovered that there were so many animals near their homes that they had never seen before and never would have seen but for participation in the organization. They only saw the dead. Many people would reflect on this afterwards, and contemplate the human activities that lead to roadkill. Subsequently, they became very involved, and they started looking for friends to join too. Slowly, the number of people in TaiRON increased.”(Mr. Lin, 26 March 2017)

Mr. Lin stated, “the most interesting thing about citizen science is that many experts are active in our community, and they offer their expertise and share ideas and suggestions when we encounter problems.”(From the Reporter News, 27 December 2016)

“Even members in the United States—in New York—provided suggestions and assistance on an initiative to develop an app for us to use to maintain records.”[37]

4.4. Improvement of Environmental Literacy for Sustainability

“TaiRON has become widely known in Taiwan. Five years ago, if you mentioned the roadkill group, no one would know what it was. Everyone would be very puzzled, and say things like, why did you get into this kind of thing? People would think that it was a group of freaks.”(Mr. Lin, 26 March 2017)

“After joining TaiRON, everyone treated me as a pariah and blocked me out because they would see pictures of dead animals on their Facebook feed. Many people were unnerved, but later, they came to understand that concern for the death of these animals was not some weird and horrific preoccupation—this realization was helpfully assisted by media reports of our activities. People came to realize that the dead animals are a critical signal of a problem in the environment, and that all our health could be endangered.”(Mr. Lin, 26 March 2017)

“I think the roadkill group is quite different because it is addressing a problem across all the species, and it involves diseases, pesticides, and safety issues. Everyone in the group has a very special background. Most of the 10,000 people are not specialists in ecology or wildlife biology, and largely come from a diverse variety of social strata.”(Mr. Lin, 26 March 2017)

“Apart from joining a community of like-minded people, our members began to observe the environment to determine if there were any problems near their own homes. For example, is there a place where many trees were suddenly felled? After the felling, animals would have no place to hide, so they would run out into the road and often be crushed to death. Or, if there is a road that has a design problem that has become a major thoroughfare, then traffic becomes very busy and hazardous to the animals.”(Mr. Lin, 26 March 2017)

5. Discussion

“All of a sudden, Facebook became popular, and some people began to rummage into their cabinets to pull out slides and photos taken ten years ago, or two decades ago—as long as it was road killed! Then, they uploaded it…. Anyway, Facebook is free. If it fails, we have no loss or stress.”(Mr. Lin, 26 March 2017)

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Delaney, D.G.; Sperling, C.D.; Adams, C.S.; Leung, B. Marine invasive species: Validation of citizen science and implications for national monitoring networks. Biol. Invasions 2008, 10, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lintott, C.; Schawinski, K.; Bamford, S.; Slosar, A.; Land, K.; Thomas, D.; Edmondson, E.; Masters, K.; Nichol, R.C.; Raddick, M.J.; et al. Galaxy Zoo 1: Data release of morphological classifications for nearly 900,000 galaxies. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2011, 410, 166–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McCaffrey, R.E. Using citizen science in urban bird studies. Urban Habitats 2005, 3, 70–86. [Google Scholar]

- Pattengill-Semmens, C.V.; Semmens, B.X. Conservation and management applications of the reef volunteer fish monitoring program. In Coastal Monitoring through Partnerships; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2003; pp. 43–50. [Google Scholar]

- Bonney, R.; Cooper, C.B.; Dickinson, J.; Kelling, S.; Phillips, T.; Rosenberg, K.V.; Shirk, J. Citizen science: A developing tool for expanding science knowledge and scientific literacy. BioScience 2009, 59, 977–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasny, M.E.; Bonney, R. Environmental education through citizen science and participatory action research. In Environmental Education and Advocacy: Changing Perspectives of Ecology and Education; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2005; pp. 292–320. [Google Scholar]

- Merenlender, A.M.; Crall, A.W.; Drill, S.; Prysby, M.; Ballard, H. Evaluating environmental education, citizen science, and stewardship through naturalist programs. Conserv. Biol. 2016, 30, 1255–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wenger, E. Communities of Practice: A Brief Introduction. 2011. Available online: http://www.ewenger.com/theory/ (accessed on 20 July 2015).

- Wenger, E. Communities of practice and social learning systems. Organization 2000, 7, 225–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenger, E. Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning, and Identity; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Shirk, J.; Ballard, H.L.; Wilderman, C.C.; Phillips, T.; Wiggins, A.; Jordan, R.; McCallie, E.; Minarchek, M.; Lewenstein, B.V.; Krasny, M.E.; et al. Public participation in scientific research: A framework for deliberate design. Ecol. Soc. 2012, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruger, L.E.; Shannon, M.A. Getting to know ourselves and our places through participation in civic social assessment. Soc. Nat. Res. 2000, 13, 461–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raddick, M.J.; Bracey, G.; Carney, K.; Gyuk, G.; Borne, K.; Wallin, J. Citizen science: Status and research directions for the coming decade. AGB Stars Related Phenom. Astron. Astrophys. Decadal Surv. 2009, 2010, 46p. [Google Scholar]

- Conrad, C.C.; Hilchey, K.G. A review of citizen science and community-based environmental monitoring: Issues and opportunities. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2011, 176, 273–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, C.; Abrams, E.; Reitsma, R.; Roux, K.; Salmonsen, L.; Marra, P.P. The Neighborhood Nestwatch Program: Participant outcomes of a citizen-science ecological research project. Conserv. Biol. 2005, 19, 589–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carballo-Cárdenas, E.C.; Tobi, H. Citizen science regarding invasive lionfish in Dutch Caribbean MPAs: Drivers and barriers to participation. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2016, 133, 114–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trumbull, D.J.; Bonney, R.; Bascom, D.; Cabral, A. Thinking scientifically during participation in a citizen-science project. Sci. Educ. 2000, 84, 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council, N.R. Learning Science in Informal Environments: People, Places, and Pursuits; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Crall, A.W.; Jordan, R.; Holfelder, K.; Newman, G.J.; Graham, J.; Waller, D.M. The impacts of an invasive species citizen science training program on participant attitudes, behavior, and science literacy. Public Underst. Sci. 2013, 22, 745–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toomey, A.H.; Domroese, M.C. Can citizen science lead to positive conservation attitudes and behaviors? Hum. Ecol. Rev. 2013, 20, 50–62. [Google Scholar]

- Bäckstrand, K. Civic science for sustainability: Reframing the role of experts, policy-makers and citizens in environmental governance. Glob. Environ. Polit. 2003, 3, 24–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenger, E.; McDermott, R.A.; Snyder, W. Cultivating Communities of Practice: A Guide to Managing Knowledge; Harvard Business Press: Brighton, MA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Storck, J.; Hill, P.A. Knowledge diffusion through “strategic communities”. Knowl. Commun. 2000, 65–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesser, E.L.; Storck, J. Communities of practice and organizational performance. IBM Syst. J. 2001, 40, 831–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasko, M.M.; Faraj, S. “It is what one does”: Why people participate and help others in electronic communities of practice. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. 2000, 9, 155–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hey, T.; Trefethen, A.E. Cyberinfrastructure for e-Science. Science 2005, 308, 817–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubé, L.; Bourhis, A.; Jacob, R. The impact of structuring characteristics on the launching of virtual communities of practice. J. Organ. Chang. Manag. 2005, 18, 145–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenger, E. Supporting communities of practice. A survey of community-oriented technologies. Draft 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubé, L.; Bourhis, A.; Jacob, R.; Koohang, A. Towards a typology of virtual communities of practice. Interdisciplin. J. Inf. Knowl. Manag. 2006, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lave, J.; Wenger, E. Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Bathmaker, A.M.; Avis, J. Becoming a lecturer in further education in England: The construction of professional identity and the role of communities of practice. J. Educ. Teach. 2005, 31, 47–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemphill, D.; Leskowitz, S. DIY activists: Communities of practice, cultural dialogism, and radical knowledge sharing. Adult Educ. Q. 2013, 63, 57–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murillo, E. Communities of practice in the business and organization studies literature. Inf. Res. 2011, 16, 16. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Horst, D. Social enterprise and renewable energy: Emerging initiatives and communities of practice. Soc. Enterp. J. 2008, 4, 171–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedlock, B. From participant observation to the observation of participation: The emergence of narrative ethnography. J. Anthropol. Res. 1991, 47, 69–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.-E. The Workshop of Road Ecology and the 2nd Annual Meeting of Roadkill Group. Nat. Conserv. Q. 2014, 86, 81–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.-E.; Li, J.-J.; Yao, C.-T.; Chen, C.-Y.; Chen, Y.-K.; Hsu, C.-H.; Deng, D.-P. A Brief Introduction to Taiwan Roadkill Observation Network. Nat. Conserv. Q. 2015, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonney, R.; Shirk, J.L.; Phillips, T.B.; Wiggins, A.; Ballard, H.L.; Miller-Rushing, A.J.; Parrish, J.K. Next steps for citizen science. Science 2014, 343, 1436–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Beneficiary | Benefits |

|---|---|

| Scientific Community |

|

| Volunteers |

|

| Education Community |

|

| Society |

|

| Element of Community of Practice Theory | Observation Concerning TaiRON |

| (1) Humans are social | TaiRON is a fully interactive community in which members confer to identify dead species on roadside, discuss ecological issues, and jointly participate in conducting surveys. |

| (2) Knowledge is valuable for work and other tasks and activities | The knowledge provided by each person is valuable; for example, the species that each person specializes in are not the same, and therefore a membership with various specialties is of considerable value for collectively determining the type of species that a dead animal is. |

| (3) People are motivated to seek knowledge to pursue careers and participate in activities | Members hope to learn to recognize species through acquiring environmental knowledge by communicating with each other, and this knowledge can help members participate in the investigation. |

| (4) Experiences and actions are the final outcome of learning from which we assemble the ultimate meaning of our activities | * In addition to completing surveys, volunteers also hope to see TaiRON contribute to policymaking. Therefore, members are inspired to learn within the community and constantly improve their abilities to collect more accurate information. In addition to enhancing their own abilities, members hope to contribute to society. |

| Three Core Elements of the Community of Practice Theory | Analysis of the Research Data (Source: TaiRON’s Official Website) |

| Domain |

|

| Community |

|

| Practice |

|

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hsu, C.-H.; Lin, T.-E.; Fang, W.-T.; Liu, C.-C. Taiwan Roadkill Observation Network: An Example of a Community of Practice Contributing to Taiwanese Environmental Literacy for Sustainability. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3610. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10103610

Hsu C-H, Lin T-E, Fang W-T, Liu C-C. Taiwan Roadkill Observation Network: An Example of a Community of Practice Contributing to Taiwanese Environmental Literacy for Sustainability. Sustainability. 2018; 10(10):3610. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10103610

Chicago/Turabian StyleHsu, Chia-Hsuan, Te-En Lin, Wei-Ta Fang, and Chi-Chang Liu. 2018. "Taiwan Roadkill Observation Network: An Example of a Community of Practice Contributing to Taiwanese Environmental Literacy for Sustainability" Sustainability 10, no. 10: 3610. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10103610

APA StyleHsu, C.-H., Lin, T.-E., Fang, W.-T., & Liu, C.-C. (2018). Taiwan Roadkill Observation Network: An Example of a Community of Practice Contributing to Taiwanese Environmental Literacy for Sustainability. Sustainability, 10(10), 3610. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10103610