1. Introduction

In a world with an ever-growing population, creating efficient, sustainable, safe and healthy food provisioning systems has become more vital, due to the fact that, besides fresh water, food is the most important natural resource in the world [

1]. The largest part of food sales and distribution is done by large conventional food supply chains that represent a network of food-related organizations within which products move from the producers to the end customers. However, because of this, food systems organized in a way which ‘disconnects’ producers from consumers [

2], may cause problems such as: extensive food waste, food security, environmental damage, unfair distribution of added value and profits among chain members and so forth, as well as provide reasons for an increasing interest in the quality of food, locally produced food and food producing practices [

3]; consequently, the interest in food supply chains different from the conventional ones has increased rapidly. New food chains in which shortening the food chain and emphasizing the relationship between producer and consumer are key elements have been established [

4]. From the agricultural market’s point of view, those so-called short food supply chains (SFSC) are an alternative to traditional supply chains [

5], having only a few intermediaries between the producer and the consumer and/or a short distance, geographically, between the two [

6]. As such, SFSC fully respects the principles of sustainability (economic, environmental and social) and provides progressive opportunities for the aforementioned. Firstly, it participates in the economic reinforcement of a country by advocating the boost of food producer’s incomes (sustaining small farms and business). An SFSC represents a network, throughout which products move from production to consumer point, where the number of middlemen is minimal (in direct contact between producers and consumers there are no intermediaries). That way, SFSC makes a contribution by setting up the selling price competitive with the price in a global food supply chain market (middlemen’s fee is excluded and selling price is easier to control). For example, in a global conventional food supply chain, consumers are buying food at a three to four times higher price than the price paid to producers [

7]. Next, it is proved that SFSC has a positive impact on the employment rate. Furthermore, an SFSC reinforces a sense of the prevalence for the agricultural sector towards a sustainable society and impacts the social development of a region (more specifically rural territory) by preserving local communities and social justice (strengthening local economies). Finally, environmental criteria are also influenced by SFSC. Since producers have a greater number of interactions with final consumers, they can adopt more reasonable agricultural methods, by reducing the use of chemical products in this field for example, upon the request of the end users [

8].

Although SFSCs are of recent date, they have been widely studied [

4]. Aspects such as the role of producers/farmers in SFSC [

5,

9], the type, characteristics, structure and business models of SFSC [

10,

11,

12,

13], the SFSC potential impact on society, economy and environment [

14,

15], the customer expectations of and their preference towards SFSC [

16], have been studied in detail. Also, SFSCs have been studied by many research programs [

2,

17], which give us a broad overview of realized SFSC case studies. However, the literature written from a distribution and logistics operations point of view is not as available, although this is something which is becoming increasingly applicable and important in agriculture [

18] and it is one of the main challenges of setting up an efficient and sustainable SFSC. Actually, there has been a number of papers written in recent years which provide a description and optimization of food supply chain operations (a very systematic literature review of such kind of papers is done in Reference [

19]) but not in the context of SFSC. According to analyzed case studies provided in Reference [

17], the main barriers facing SFSC from the operating/process aspect are ‘lack of specialized knowledge such as IT, logistics and accountancy skills’ and from the sales aspect ‘poor Internet service and unreliable distribution’. Hence, as they conclude in Reference [

18], ‘recognition of logistics and distribution as a separate service within the food chain’ represents the basic factor of SFSC success. As the same authors further stated that ‘distribution and logistics for SFSC have to be smart, simple, quick, flexible, cheap, transparent and reliable’, we have added one more word in our paper—‘sustainable’.

Conceptually, an SFSC represents a (direct) connection between individuals that ‘yield crops’ and communities that consume goods. Thereupon, the key point here is: how to connect those two types (and their motives) so that the appropriate food reaches the right place at a suitable time, having acceptable quality, quantity and price [

20]? The problem is that SFSC implies fewer middlemen. Hence, producers have to pay much more attention to marketing and distribution of their products, which is not at the core of their business. As it was stated in Reference [

8], this approach is feasible, in certain ways, for direct sales, while for indirect sales volumes are more significant, considering that a supply chain has to be properly designed in order to organize the flow of goods and minimize transportation costs so one can become competitive with the global supply chain. Thus, the ‘challenges regarding the distribution of food in SFSC are related to the issue of cost related justification towards the realization of logistics activities’ [

20], due to the lack of a suitable logistical delivery infrastructure. In addition, the fact that the food is perishable and that the transport and management of it are regulated by complicated legal provisions, makes the issue more complex. Therefore, SFSCs require corresponding innovative logistics solutions within food delivery systems that follow the contemporary logistics trends (digitalization, reducing costs, sustainability, improving flexibility and responsiveness to customer demand, etc.), while appreciating the specificities of distribution context of locally produced food.

The basic motivation for this study was to recognize the need to find the effective solution for a more sustainable and efficient distribution system in SFSC. As it was previously stated, we could find opinions in literature about the significance of a SFSC concept but there is no shared opinion on an appropriate operations model of the physical distribution of the food, which is the main challenge of SFSC. Distribution models are very expensive, especially in cases of delivery to less populated places, long transport distances and when “cold chain” conditions are required [

21]. Also, as it is stated in Reference [

17] very little research has been done to develop tools and data for understanding the effects of SFSC taking into account the economic, environmental, social and health aspects. Therefore, the purpose of this paper is to describe several different operational models for food delivery in SFSC, based on innovative solutions and approaches, using business process modelling (BPM) tool and then explore their features in more detail from several different aspects with the main focus on sustainability. In order to achieve this purpose, the following objectives were devised:

to develop the operational models and organizing formats of distribution of locally produced food within SFSC. Therefore, by using business process modelling (BPM) we showed how SFSCs could be designed from aspects of innovative ICT and contemporary logistics approaches (third party logistics, home delivery services). Created business process models that depict the sequence and interactions of control and coordination activities among different distribution scenarios could be used as a base for further development of business models.

to conduct a comparative assessment of the distribution models detailed in the first task, in order to evaluate them from the aspect of sustainability. Sustainability assessment and comparison followed the specially developed framework, based on a similar framework found in literature, which makes the dimensions, inputs and possibilities of different distribution solutions in SFSCs visible.

The ultimate aim of this paper is to provide a qualitative analysis of the fit among locally produced food delivery innovative services, requirements and issues that users of service providers might have. The analysis result could help the decision-makers in SFSC choose an appropriate concept of SFSC development, especially in regions with a low level of SFSC concept maturity.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. The next section describes applied research methodology. First, it briefly reviews the related literature about the key concepts of the chosen topic: SFSC, logistics innovation, logistics distribution sustainability, logistics service providers and BPM. After that, we generated a problem statement with a conceptual definition of a modeling object and developed a conceptual model for sustainability assessment. The third section illustrates the application of BPM in the modeling of different food distribution scenarios and determines a qualitative analysis regarding sustainability. The fourth section discusses the results. Finally, concluding remarks are made in the last section.

2. Methodology

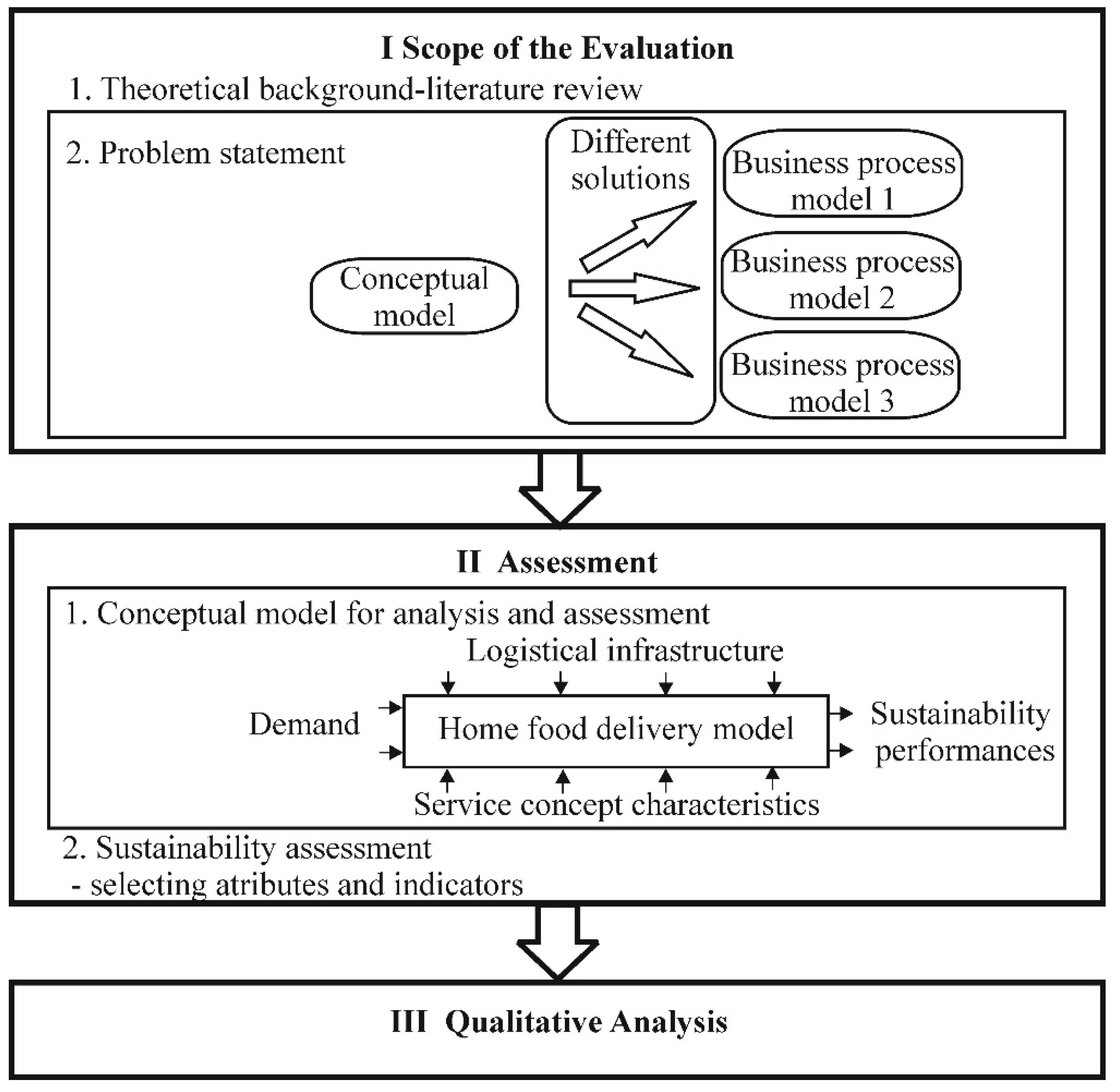

The research is based on methodology whose schematization framework is described in

Figure 1, (based on the framework in Reference [

22]). With the aim of understanding how distribution processes in SFSC could be set up and organized and of assessing their sustainability features, the following approach is used. Firstly, the scope of evaluation was defined. This step first included a literature review regarding the main key words and concept surrounding the stated research problem (literature review on SFSC, sustainable freight distribution, innovative logistics approaches, digitalization, logistics service providers and BPM). After that, solutions to distribution processes in SFSC were conceptually defined and appropriate operating models were created using the BPM tool. For this first part of the research, the used research methodology is design-oriented [

23,

24], which typically involves “how” questions, that is, how to design a model or a system that solves a certain problem. The research here applied a conceptual design and modelling approach, in which a theoretically-based conceptual model (or domain model) of the possible solution is developed first and after that, the applicability of the designed conceptual model is tested through detail modelling of possible solutions through BPM (

Figure 1).

For the second step—the assessment of proposed solutions to food distribution with the emphasis on sustainability—one more conceptual model is developed. Based on models in Reference [

25,

26] we create a conceptual model primarily to analyze basic features of different distribution model scenarios and then to access their sustainability performances. For sustainability assessment, a set of attributes and indicators of performance were selected, derived from the literature [

7,

22]. A complete model description is given in

Section 2.3. Hence, the second part of the research is conducted by using a qualitative approach where a specially developed framework is applied in order to analyze and assess features of the proposed distribution models from several different aspects with the main focus on sustainability.

2.1. Theoretical Background

2.1.1. Short Food Supply Chain

Short food supply chain, also commonly termed in literature as direct or local food supply chain, can be identified by two basic characteristics: ‘food production, processing, sales and consumption that are carried out in a relatively small geographic area (territory) and the number of mediators (or middlemen) in the chain which is minimal’ [

2,

20]. Thus, based on [

2,

6], the food supply chain can be defined as “short” when there are distinguished short distances (the distance as a physical dimension that covers a range in which a product passes between the starting and ending point in the chain), or only a few (or zero) intermediaries between producers and consumers (the distance as the social dimension, which involves direct interaction and exchange of information between producers and end users).

SFSC was originally identified as an example of “resistance” of farmers to modernize their system of production and distribution of food, characterized by the development of global retail chains. The resistance reflected in the fact that direct sales to consumers bypass intermediaries, thereby creating the possibility for the increase of profits for producers, creating better visibility and identifying new niche markets. Based on wide literature review, the authors in paper [

4] derived four prevalent characteristics of SFSC:

geographical proximity, which refers to a geographical area in which food is produced and/or distributed;

economic viability of included actors, mainly from the primary producers’ point of view;

social interaction, which refers to the producer-consumer relationship and interaction within communities;

environmental sustainability.

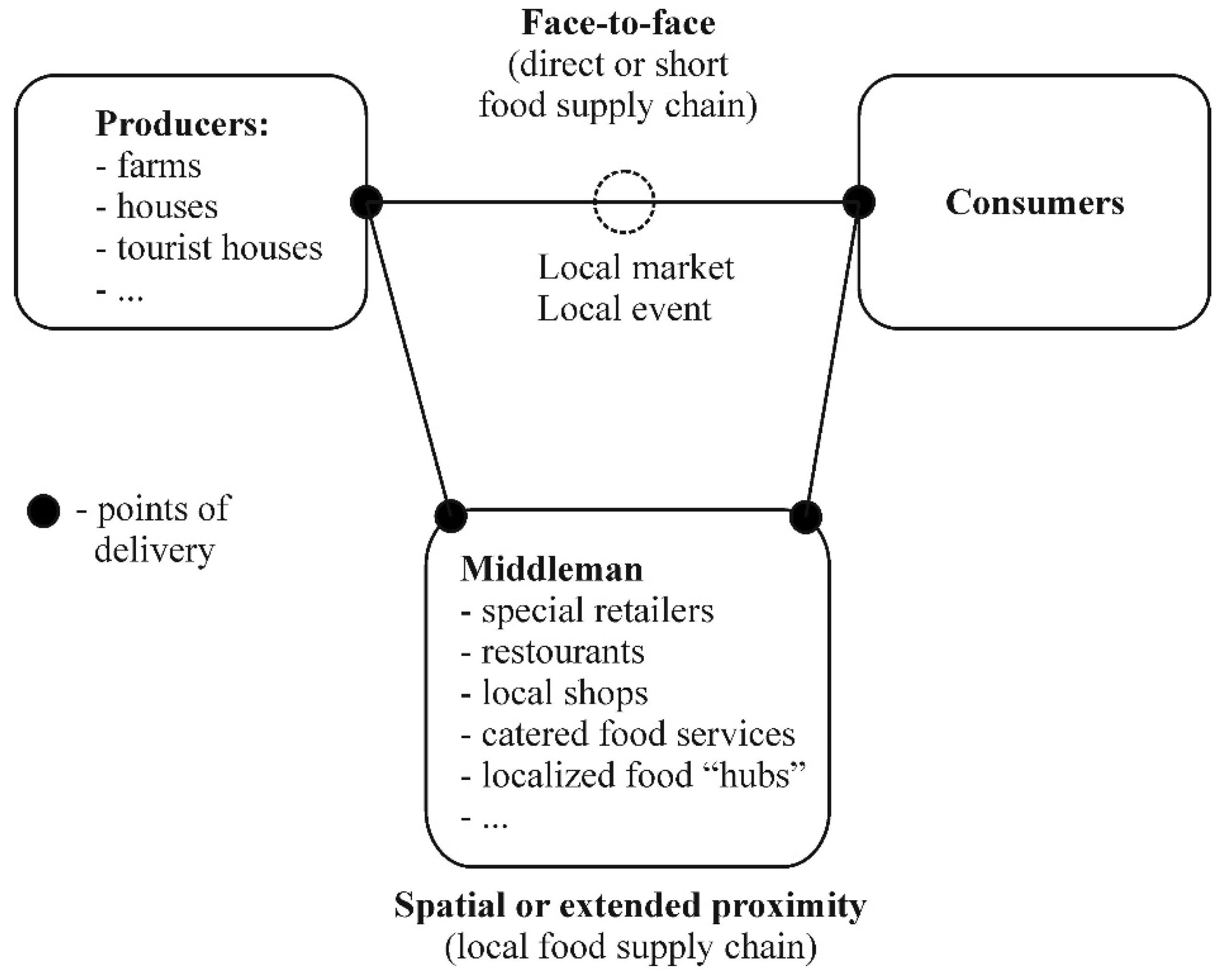

Taking into account both geographical proximity and social characteristics, there are three basic types of SFSC that are suggested in Reference [

4,

20,

27]:

SFSC which implies direct contact between the producers and the consumers and sells on a face-to-face basis (direct marketing).

SFSC which assumes selling local products through local market channels such as farm retail markets, food service outlets, local food retailers and supermarkets (proximate instead of direct relationship between producers and consumers).

SFSC which presumes selling local food products not only to local consumers but also to all others (extended relationships).

The focus on alternative food systems in scientific literature very often hides a larger reality concerning local food networks [

12]. The tradition of selling and consuming local foods is long-standing in Europe but its role decreased with the industrialization and technical/technological innovations. One of the first countries which renewed the interest in developing such kind of food systems through the creation of a formal definition, public affirmative initiatives and acknowledgement by policy-makers was France. They officially defined SFSCs as ‘selling systems involving no more than one intermediary’ [

12]. Other industrialized nations have applied similar initiatives. However, no universal definition of what constitutes an SFSC exists [

28] but it could be claimed that its structure depends on provided answers for several basic questions: how, where and by whom the food is produced; in what way and who is responsible for food distribution; who are the consumers and what are their expectations; what are the organizational forms of the actors in the chain; and how significant is the influence of new (digital) technologies? By providing answers to those questions, one can figure out how SFSCs are “built, shaped and reproduced over time and space” [

29]. According to this, a general scheme of SFSC structure could be formed, as it is shown in

Figure 2, where a slight difference between terms “short” or “direct”, on the one hand and “local” food supply chain, on the other, has been made. The term “local” is focused on distance (locally produced foods are sold to local consumers). The term “short” concentrates on the reduction of the number of middlemen and it implies a more “direct” route [

29]. Hence, “short” or “direct” food supply chain may involve the sale and distribution of locally produced foods on long distances (spatially extended).

SFSCs were for the most part developed in specific regions and in specific sectors (for example honey, fruit, vegetables, etc.) [

12], so it could be claimed that SFSC operates in a specific business environment, where food producers need to be more dynamic and active in cooperation with other firms within the supply chain network and to create a stronger relationship with the customer [

20]. It is particularly important to achieve the closest possible cooperation among different small food producers, especially in the field of logistics activities and their realization. That way, logistics cost reduction, better utilization of the resources, improved reliability and efficiency of the deliveries can be obtained [

10] (issue of economic and environmental sustainability).

Generally, producers of local foods use two main forms of distribution channels to reach their customers: direct distribution and the use of intermediaries. As it is stated in Reference [

28], both of those forms can be organized in a myriad of ways. In the case of direct distribution, sales could be realized directly at points of food production (farms, houses, etc.), or through local markets, localized exhibition events and so forth (

Figure 2). The middleman in SFSC makes a bridge between producers and consumers in terms of marketing, selling and delivering [

11]. The food producers could supply their products directly to the middleman or could just prepare them to be picked up by the middleman (special retailers, local shops, catering food services, localized food hubs). The middleman is in charge of marketing and sale of goods, or even of direct delivery to the consumer’s door. The main issues of such systems are related to the problem of the organization and realization of logistics and distributive activities in a cost effective and sustainable way [

10]. In relation to logistics, the basic question includes how to plan, organize and realize activities such as storing, transporting and handling food within its flows from producers to consumers. Generally, particular logistics or supply chain management (SCM) strategy, which defines the ways of how goods are moved, stored and handled, depends on wide range of factors [

30]. The basic objective of SCM strategy is to establish new and cutting-edge methods and techniques for the improvement of logistics efficiency, competitiveness and sustainability.

2.1.2. Sustainable Freight Distribution

Sustainable development, generally, has to meet the needs of the present generation without claiming to have the ability to meet the needs of future generations [

31]. As it is stated in the same paper, this definition of sustainable development could be divided into three dimensions: economic affordability, social acceptability and environmental efficiency. ‘Sustainable development requires radical and systemic innovations’ [

32]. According to the same authors, such innovations could be more effectively created and studied when building on the business models’ concept, so we adopted this argument in our paper. Sustainability has also become an arena of competition among firms [

33]. The increase of the consumers demanding care for the environmental, social, ethical and health attributes, influences companies to respond appropriately.

Freight or logistics distribution assumes a number of different types of goods flows (raw materials, semi-finished products and manufactured goods) that should be realized (moved) in an appropriate manner through distribution channels. Therefore, freight distribution represents the term for the range of activities (transportation, handling, warehousing, packaging, etc.) involved in the movement of goods from the very beginning (point of production) to the point of consumption. The main challenge in freight distribution is to organize distribution activities as efficiently as possible, while taking into consideration requirements from both supply and demand sides, with regard to sustainability as well. The nature of the freight distribution systems is switching from the more traditional (simply holding the inventory) towards a business model that relies on stronger information relationships with customers and suppliers. Structural changes in distribution channels currently taking place are accelerating deliveries to customers [

34], so it could be said that they are becoming increasingly demand driven [

35]. As it is noticed in Reference [

34], these contemporary distribution channel structures have proved to be both extremely cost efficient and effective in improving customer services. Distribution channels could be organized in particular ways which then could be compared and analyzed by various approaches. In our paper, an integrated performance assessment across four dimensions (environmental, social, economic and health) is provided in order to explore and compare different delivery solutions.

2.1.3. Innovative Logistics Solutions

When defining the acknowledgeable Logistics and Supply Chain Management (SCM) strategies, companies face a number of limiting factors which are the consequences of the changes which occurred in the global economic surroundings [

30]. Those changes, in the form of new trends, affect the business strategy on which the choice of logistics strategy and the operative solutions derived from it are directly dependent.

External forces of change (such as changing customer requirements, increased competition, government regulatory changes, technological advancements, increased emphasis on efficiency and on sustainability, security and resilience, etc.), drive the business strategy while strategies of competitiveness are shaped by the business strategy [

30]. This means that external force of change impacts the changes in business and strategies of competitiveness, which in the end cause changes in SCM strategy in the form of new and innovative logistics approaches and methods based primarily on modern digital technologies. Such an innovative logistics solution enables business development to ensure flexibility and prompt market response in an increasing competitive environment. According to [

36], this is particularly interesting to small and medium enterprises (such as for example local food producers) that are required to be flexible, adaptive, innovative and sustainable organizations. Those digital-based innovations may also improve the seller-buyer relationship in both directions. The sellers could be able to offer their products to a larger number of customers than with traditional marketing and distribution channels, with higher possibilities to improve their performance (reduce inventory). On the other hand, the customers could have possibilities to choose among a wider range of product options [

36,

37].

In forthcoming years, business strategies will become more customer-oriented, reflecting the shift in the forces of changes towards meeting customer requirements. However, customer requirements are no longer based only on the speed and cost of services but also on their sustainability. Therefore, there is a demand for a “logistics transformation”, which includes changing the context of “product” of logistics industry in terms of end-users [

20]. The change of the context of “logistics services outcomes” affects adjustments in the sense of logistics processes realization, which are usually based on the use of modern ICT (business digitalization) [

20]. Thus, the reported “logistics transformation” will fundamentally be implemented in the forms:

of “digitalization” of basic logistics processes (realized through Internet-based solutions), and

of innovative logistics paradigms, which are completely information-based. From the distribution activities point of view, the paradigms such as 3PL (third party logistics), home delivery services and crowdsourcing have the highest potential importance.

Maybe the key word of this century is digitalization, which is present in all spheres of human activities [

38]. When it comes to logistics activities, then digitalization is a personification of the digitizing core logistics processes and virtualization of supply chains [

24] as well as using the Internet-based solutions (such as Internet of Things) for ensuring better flexibility, productivity, cost efficiency and better levels of logistics activity control. Digital technologies could bring completely new capabilities for better planning, designing, realizing and controlling the flows of goods, information and values across an extended logistics chain. That is, the improvements mainly accomplished by non-Internet technologies, such as mechanization and automation of logistics operation [

39], are no longer sufficient, so a “new” form of logistics reality is needed. When it comes to the innovations in the food supply chain industry, it assumes the use of new ICT which has to provide better cooperation and collaboration among all food supply chain partners such as producers, distributors, retail and logistics service providers. In the food sector, ICT technologies could be crucial elements for meeting the challenges of sustainable farming and food processing, food logistics and food selling. A broad application of future Internet applications is expected to change the way food supply chains are operated in unprecedented ways [

24]. Indeed, a lot of ICT research and innovation in farming (Farming 4.0) and food traceability is happening nowadays [

1]. The claim that ‘the Internet helps to reintroduce old services’ [

40], could be very helpful for improvement of the local food supply chains and SFSC due to increased access and speed of purchase of local products at traditional markets. However, not only do the Internet based services have an impact on the way in which customers order and purchase food but they also have a significant impact on the business models and physical distribution network structure. Digitalization of the food sector is dependent on a number of enabling technologies covering hardware, software, network/cloud/communication technologies and services for providing the functionalities needed by the sector [

1].

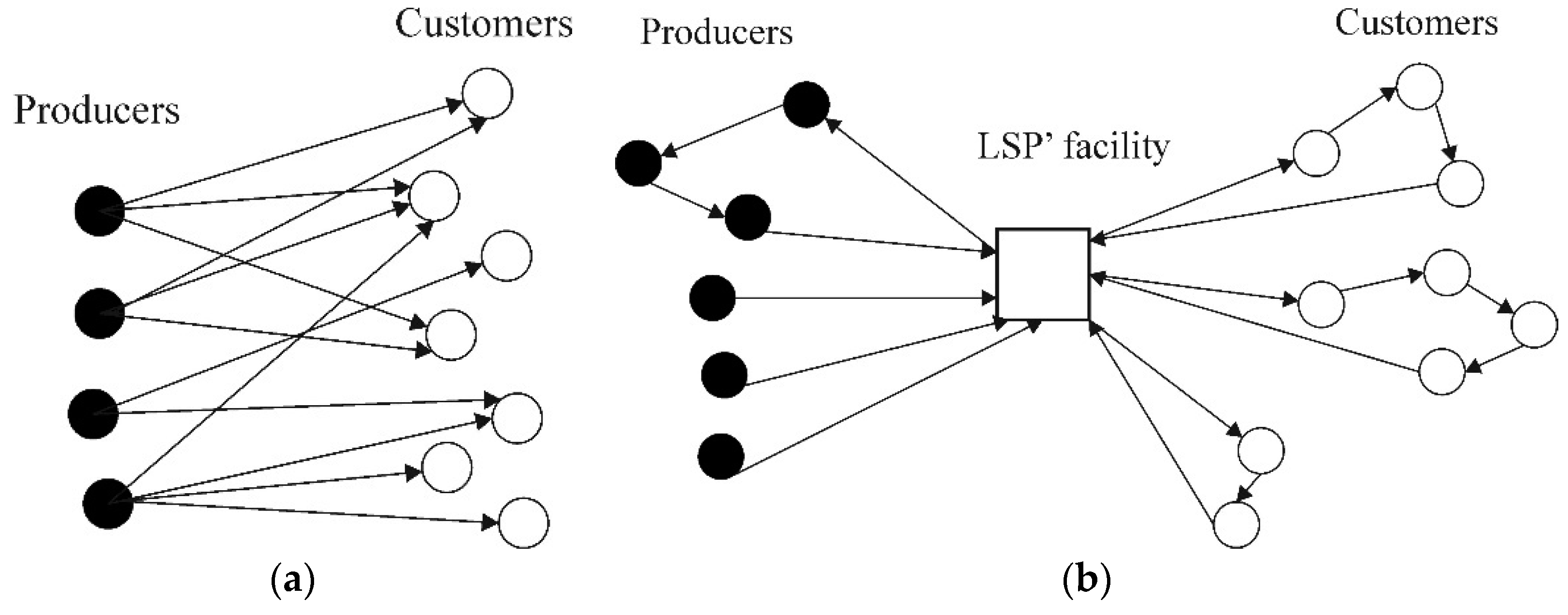

Logistics service provider or third-party logistics (3PL) provider is an external provider who manages, controls and delivers logistics activity on behalf of the shipper [

41,

42]. Indeed, a 3PL provider denotes a specific outsourcing activity related to logistics and distribution. A 3PL provider collects outbound shipments from shippers and consolidates them in their distribution centers, after which it distributes them to the receivers [

41]. The literature review showed us the existence of three stages, or waves of logistics service provider development, as it was stated in Reference [

43]: the first wave assumes increased usage, mostly transport and warehouse services, the second one is related to rapidly increased 3PL popularity and diversification of their services and the third one represents an increased interest in integrated outsourcing logistics functions [

20]. A 3PL provider could be categorized as one of four types according to their general problem-solving ability and customer adaptation: service developer, customer developer, standard 3PL provider and customer adapter [

10]. In the area of SFSC, a 3PL provider could be of crucial importance due to the fact that development of efficient SFSC is very sensitive regarding the strategies for realization logistics and distribution activities. Challenges regarding distribution of locally produced food are related to cost justification of ‘in-house’ logistics. Therefore, SFSCs could require logistics solutions which can be offered by specialized 3PL providers [

20]. However, selecting the appropriate 3PL providers for partners could be very challenging for food producers, due to both feasibility and viability of such logistics services capable of satisfying low-volume supply chain needs and uncertain business potential for SFSC intermediary businesses [

3].

The third stream of relevant logistics innovation concept review focuses on home delivery services, which is tightly connected with the 3PL concept. The term

home delivery ‘represents all goods that are consigned to customers’ homes or another site designated by customers rather than situations where customers have to personally pick up the goods or ship them in person’ [

40]. According to the same authors, functionality of home delivery is important for online shopping business models and hence it could be a crucial factor in success of online-based fulfillment and delivery processes in SFSCs. Hence, home delivery is considered a vital component mainly in the area of e-commerce, as a value-added service provided by sellers [

40]. As a matter of fact, developing the appropriate operation models of distribution of locally produced food in SFSCs, as one of the objectives in our paper, could be categorized into home delivery service problems which have been widely researched by both academies and industries for over three decades. In the academic world, the first published paper exploring the home delivery services was in 1996 and the first industry patent about the same concept was even earlier, in 1993 [

44], after which this concept has attracted great interest in the following years [

25,

26,

40,

45,

46,

47]. Generally, the home delivery concept has been studied by two different points of view: the seller’s and the consumer’s point of view [

45]. Some of those papers investigated existing home delivery services from different angles and perspectives (investigation of the success factors) but as concluded in Reference [

26] there is no shared opinion on the most successful and applicable operations model of the home delivery concept. In Reference [

25] the appropriate framework and computer model to analyze the home delivery concepts was built, which will be used in building our conceptual model for assessment of proposed distribution models. In our paper, the objective will be definition and identification of the main value proposition, as well as the addressed issues that characterize proposed home food delivery service models, from both the consumer’s and producer’s point of view. More concretely, we analyze proposed models from the customer’s point of view (value proposition of developed models) and also from the seller’s point of view with regard to answering the question of what the issues in delivering those customer value propositions profitably are.

Crowdsourcing leverages technology to employ hundreds or thousands of individuals to perform tasks or help solve problems, thus increasing efficiency by taking advantage of underutilized assets and people [

48]. In the transport and logistics area, crowdsource assumes sharing assets and people in realization of personal travel or freight distribution activities (last mile delivery) using smart applications. The well-known service for ride-sharing is Uber, which matches people’s need to travel with excess car and driver capacity. In Reference [

49] a growing popularity of crowdsourced delivery over the past few years, with a number of online platforms, is noted. According to the same authors, the dominant business model for such kind of delivery is business-to-customer, where a parcel is picked up directly from a fixed point by a crowdsource and delivered to the customer. From the SFSC perspective, by using the crowdsourced delivery, local producers get a cheaper option for sending food bought online and private citizens increase possibilities of extra income [

44]. Crowdsourced delivery has already occurred due to the fact that consolidated companies like Amazon are testing delivery by leveraging a crowdsourced solution.

2.1.4. Business Process Modelling

As it is noticed in Reference [

50], technological advancements in ICT should be followed by appropriate business models as a reflection of innovative logistics strategy and changes in the supply chain management paradigm. Hence, utilization of innovative logistics solution based on digital technologies has to be explored in detail, in order to provide a clear picture of company’s business and logistics operating processes. An appropriate way of showing how business components are related to each other and how they operate is business process modelling.

According to [

51], a business model, or how to organize a business, is one of the five types of potential areas for industrial innovations (the business model innovation represents the changes in the logic of how firms do business). From a supply chain perspective, examples of new business models are the design of a joint distribution service, the usage of a common category warehouse, the establishment of the new forms of distribution channels and so forth [

52]. A business process is a set of logically related tasks performed to achieve defined business outcomes [

53], previously formed through a business model. It implies strong emphasis on how the work is done within an organization, thus it represents a specific order of work activities across time and place, with a beginning, an end, a clearly defined goal and inputs and outputs: a structure for action [

54].

A business process model is an abstraction of real business processes with the ultimate purpose to provide a clear picture of the enterprise’s current state and to determine its vision for the future [

50]. Hence, Business Process Modelling (BPM) is an important part of understanding and restructuring the activities and information which is a typical firm used to achieve its business goals. It is also a powerful method used for better understanding of business concerns and communication between stakeholders, allowing every interested party to be actively involved in these activities [

55]. BPM is implemented to improve existing business processes, by reorganizing the existing ways of functioning and operating certain elements which form an integral part of the business model, or to establish a new business system on certain principles which the company’s management deems necessary. The development of methods of BPM results in unifying methodology in recognized standards such as Business Process Modeling Notation (BPMN). Therefore, BPM does not represent classical programming but could be seen as programming in which a programmed language outlines a graphical notation of BPMN.

Synthesis of all these literature insights results in a theoretical framework which connects the previously discussed theories in such a way that a conceptual understanding of possible distribution models in SFSC could be obtained. Hence, using this theoretical framework, the conceptual model and various detailed scenarios of food distribution processes in SFSC could be further specified, enabling us to explore distribution activities in SFSC from different aspects.

2.2. Problem Statement and Conceptualization of Problem Solving

The involvement of SFSC implies that the farmer is not just a producer any more but also responsible for sales and marketing [

56]. Hence, producers are obliged to manage several additional activities that may come before actions which are related to the producer’s core business. One of those added activities, or the most challenging one, is logistics (transportation and distribution). As we have already stated in the introductory section, the main challenges regarding the distribution of locally produced food are connected to feasibility of the logistics activities realization in the producer’s own organization. The main concerns related to this [

20] state the following: the small shipment size and production capacities, limited technical and financial resources, high logistics costs which assume relatively high product prices. To sum up, SFSCs require contemporary and sustainable solutions in the field of food distribution, which should be based on innovative logistics approaches and new information and communication technologies. One of the ways in which this issue can be overcome is in application of digital technologies through Internet-based solutions and innovative supply chain paradigms (which are completely information-based), such as using 3PL, home delivery services and crowdsourcing in distribution activities. As it has been already mentioned, the basic motivation of this paper is to emphasize the need to find the sustainable solution for the distribution system in SFSC and the basic objective is to offer a concept for exploring and analyzing the practical ways of improving economic and ecological sustainability, as well as efficiency and competitiveness of small food producers and their supply chains, based on new ICT (cloud, web and android applications) and innovative logistics solution. That way, through the definition of appropriate business models, which should follow the application of the above-mentioned technical and technological innovations, an adequate theoretical base for the development of SFSCs with sustainable distribution based on digitization of food markets could be created.

The problem statement has stemmed from local food consumers’ dilemmas while facing a choice: whether to go and buy food themselves or buy food using some kind of home delivery services? Depending on the chosen option, among others, the volume of realized transport and associated Greenhouse Gas (GHG) emissions is different. For example, the supply of food through retail chains accounts for approximately one third of the UK’s total GHG emissions, with transport estimated to account for 1.8% of the total emissions [

19]. Based on the established theoretical framework we adopted conceptual understanding of possible solutions which are home delivery service based, due to the assumption that these kinds of solutions are more sustainable.

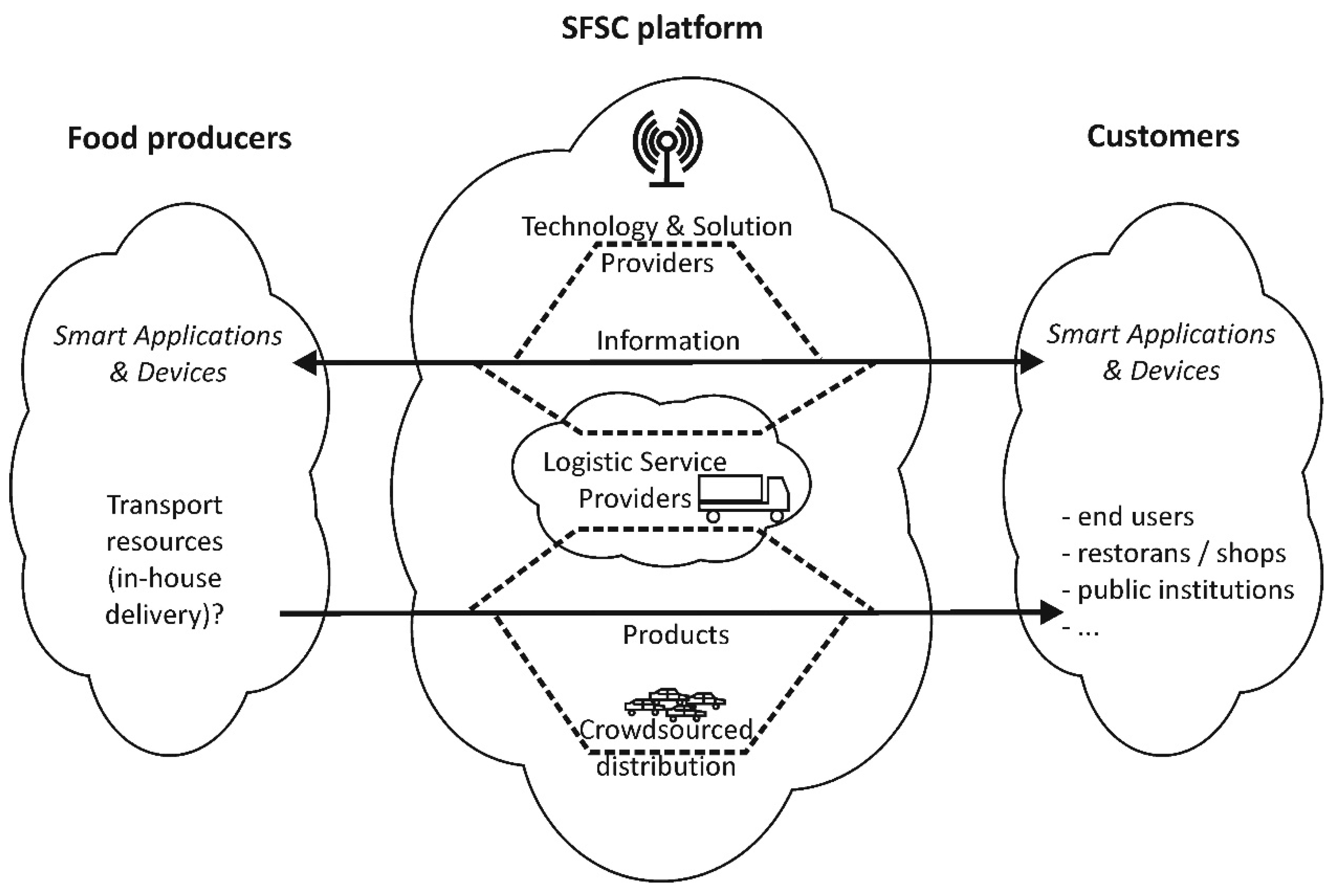

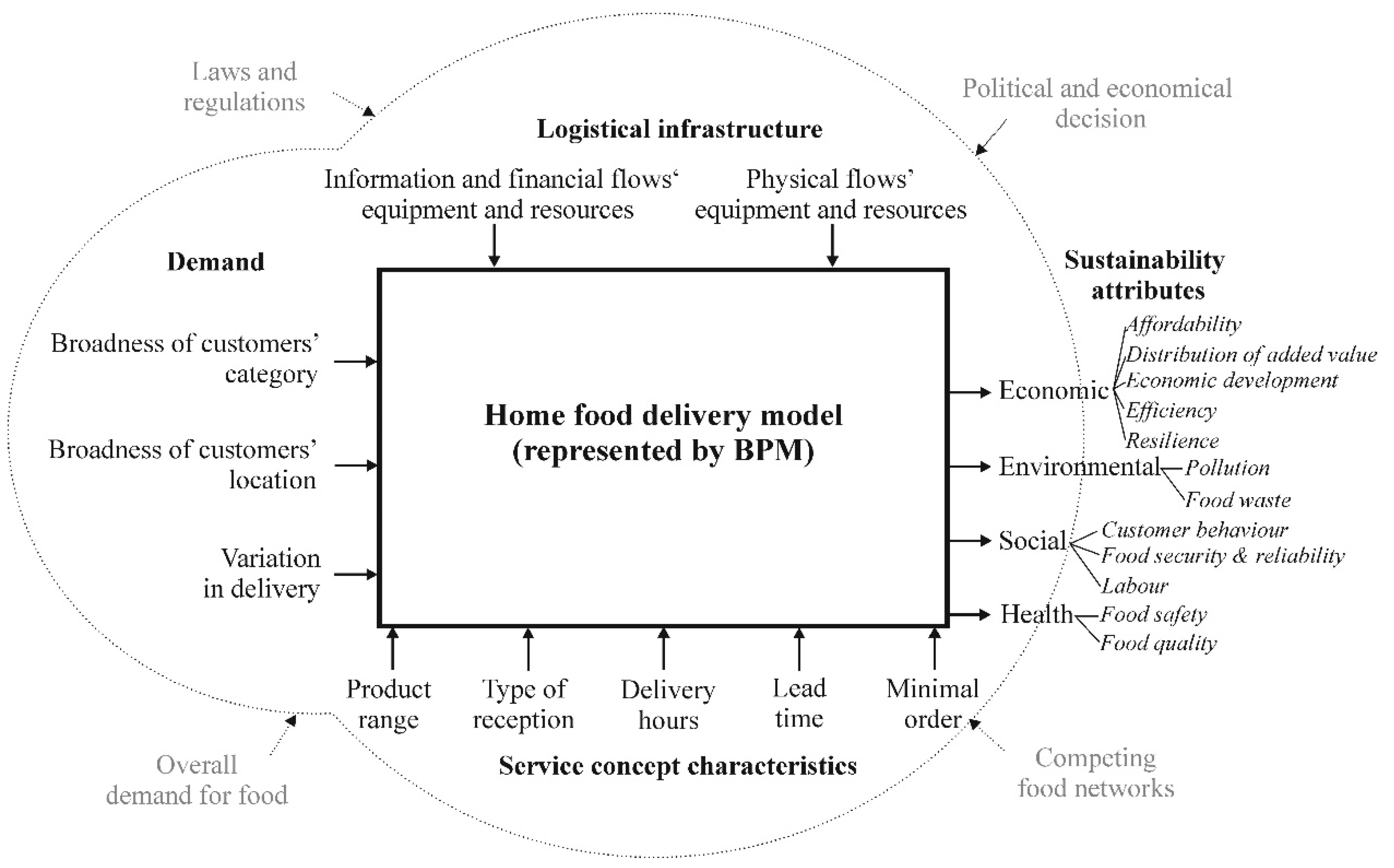

The conceptualization of the stated distribution problem solving, given through an appropriate conceptual model as a solution-independent description of the stated problem domain, is shown in

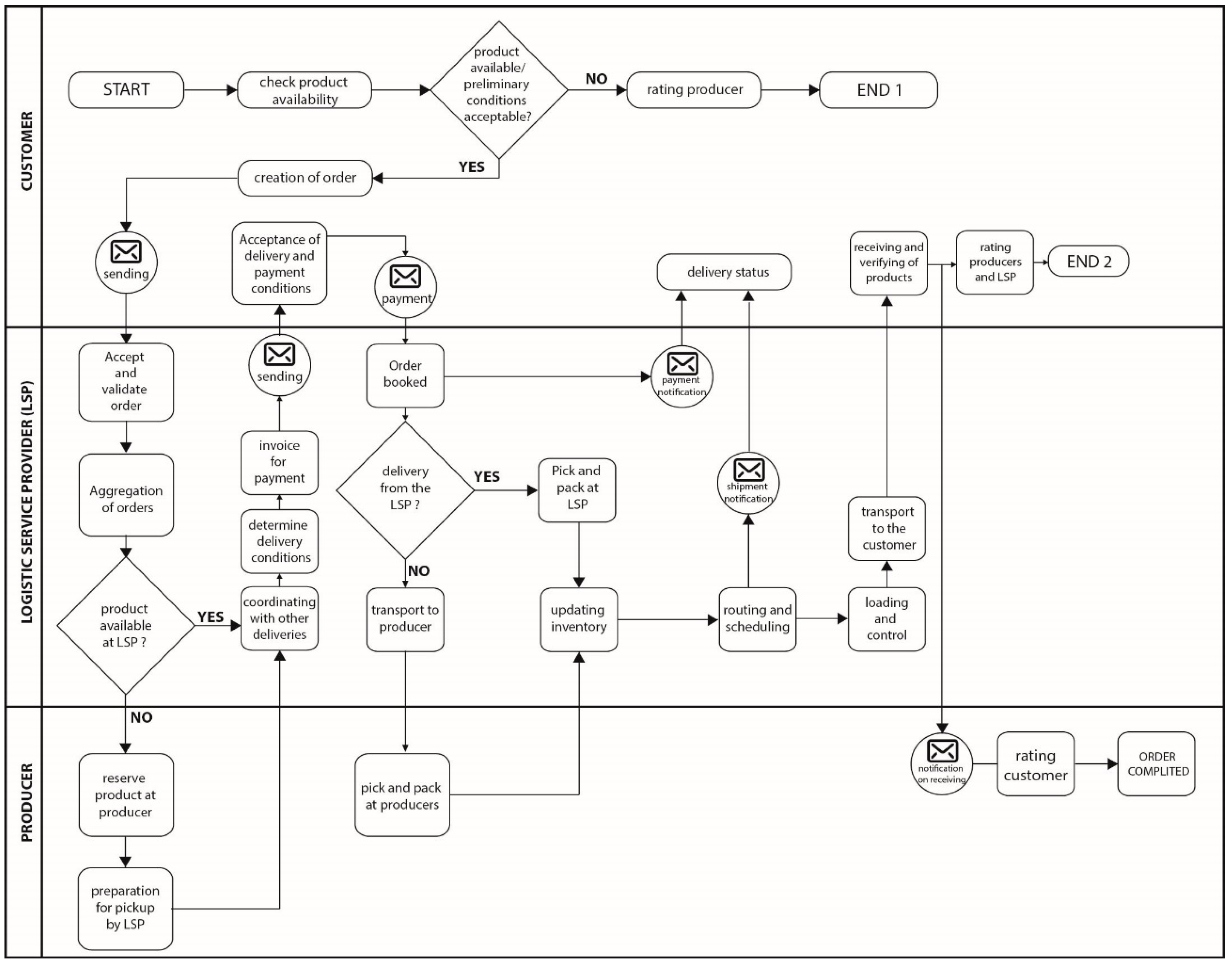

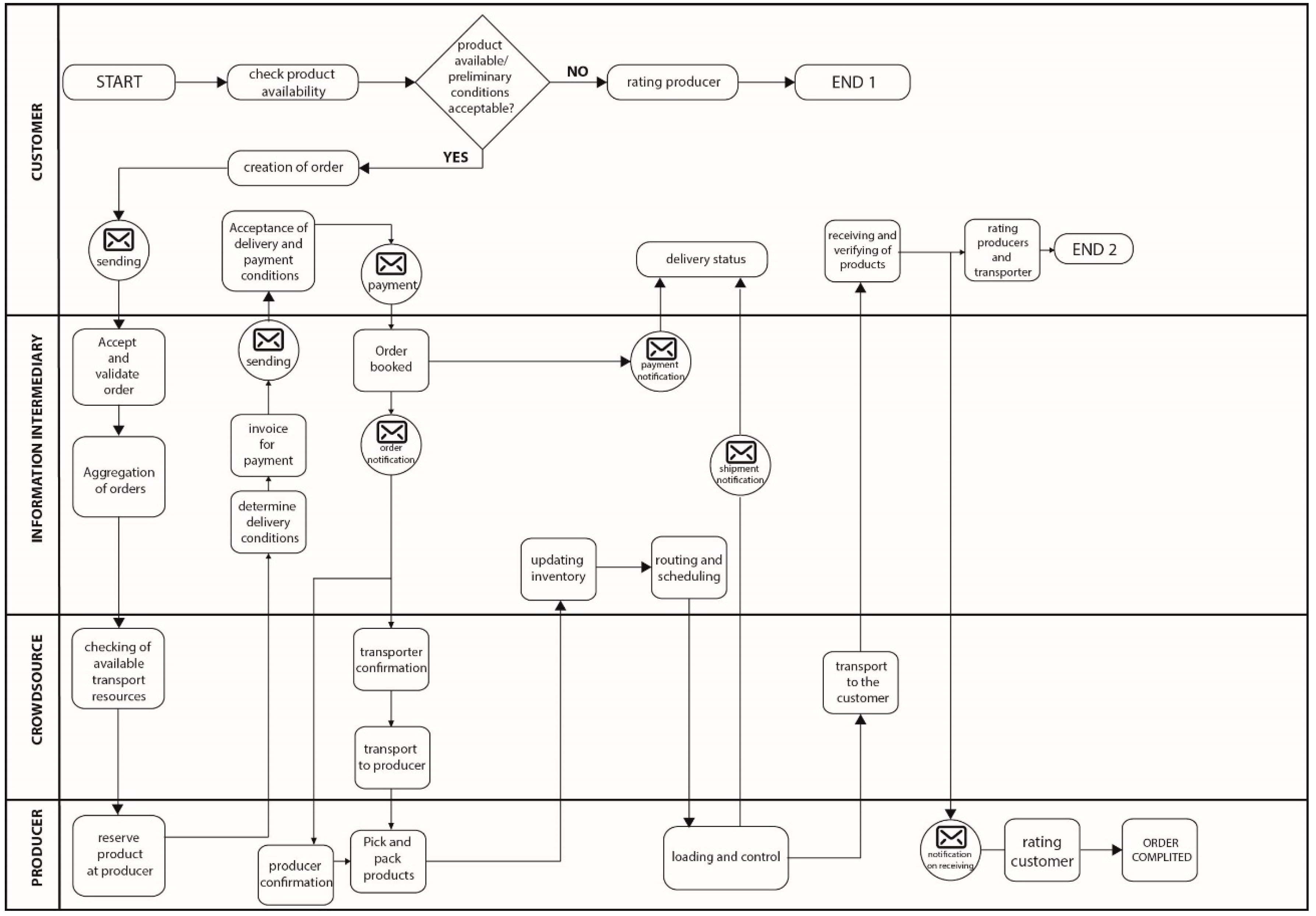

Figure 3. The proposed conceptual model includes the development of SFSC platform based on the principles of digitalization of business processes in the food market and the application of innovative logistics solutions and strategies. More specifically, the innovation of the proposed concept is based on the reengineering of the business process of local food distribution systems that would involve the usage of smart applications and devices (that enables online order placement, inventory control, dispatching and receiving management [

36]) and application of modern logistics strategies in the field of distribution that involves the existence of home delivery services provided by specialized logistics service providers or a crowdsourcing solution (with support of technology and solution providers).

The proposed conceptual model is solution-independent in the sense that it is not concerned with making any business process design choices or with other designs or planning issues. Instead, it focuses on the general challenges and solutions to the problem under consideration. In the business process models design phase, three business process models are developed. The basic building blocks in those process models are activities adopted from the two types of SFSCs: direct distribution and distribution with the use of intermediaries. The business process models are modelled in the BPMN.

2.3. Conceptual Model for Assessment

The second developed conceptual model is aimed at analysis and final assessment of the proposed food distribution solutions represented through three business process models. Based on the models introduced in Reference [

25,

26] we create a conceptual model to first analyze basic features of different distribution model scenarios and then to access their sustainability performances (

Figure 4). The proposed model examines different distribution scenarios which are defined by:

customers’ demand, characterized by broadness of their category (i.e., citizens, restaurants, shops, hotels) and location (coverage of the customers base) and variation in delivery on daily basis;

offered service concept, characterized by the product range, the type of reception, the delivery hours (and time window), the delivery lead time and minimum order;

logistics infrastructure, characterized by equipment and resources necessary for planning, realization and control of goods (i.e., transport fleet, storage space, staff), information and financial flows (i.e., real time tracking of delivery, order processing infrastructure, web design architecture, cash flow function and methods of payment, management of customer’s personal information).

Therefore, each distribution scenario could be described in more detail and analyzed within three stated segments, whereas the fourth segment of the given model is used for the assessment of distribution models’ sustainability performances. The model’s segment ‘service concept characteristics’ covers the way in which the value for customers is created by helping them solve a specific problem (customer value proposition). In other words, it covers the way in which the proposed solution helps customers get an important ‘job’ done [

57], which alternative offerings do not address [

21]. The model’s segment ‘demand’ is a customer segment through which identification of all kinds of customers characterized by specific demand and locations is possible. The third segment ‘logistical infrastructure’ covers key resources (people, technology, facilities, equipment, channels) and key activities (operational and managerial) required to deliver the value proposition to the targeted customer [

57]. This is how the proposed assessment model covers several key aspects from the “Canvas business model”, proposed by [

58], as well as the key segments that make up a business model according to [

57]. This fact could be very important and helpful in defining an appropriate business model, which should follow the definition of customer value proposition and organizational patterns, as the last step towards implementation of the selected distribution model.

As could be noticed from

Figure 4, the abovementioned three segments represent the basic descriptive aspects of a food distribution system in the SFSC context. However, there are also descriptive aspects of the environment in which SFSC operates and of which understanding is very important in the process of analyzing SFSC. In a developed conceptual model, the environment, which refers to factors that influence the distribution system but cannot be influenced from the inside of the system [

59], could be represented by four aspects: laws and regulation, political and economic decisions, overall demand for food and competing food networks. Maybe the key aspects are governmental and public initiatives, represented through appropriate legislation tools and political decisions. The institutional support for SFSCs makes it possible to solve some of the main obstacles in their setting up, such as regulatory barriers (regulations and tax systems), access to finance and skills issues [

17]. However, all stated SFSC’s environmental aspects are more oriented towards strategic decision-making in developing SFSC and they define the framework within which more operational issues are considered, such as the issue of food distribution. Therefore, these aspects will not be given much attention in the rest of the paper (reason why they are marked with a gray color in the

Figure 4).

For sustainability assessment, a set of attributes and indicators of performance were selected, derived from the pertinent literature. Based on [

7,

22] we selected twelve attributes in total from four well know sustainability categories: economic, environmental, social and health (

Figure 4 and

Table 1). We set our list of attributes, as an adequate narrow version of the list of 24 attributes basically proposed in Reference [

7] (similar to the approach presented in Reference [

32]), to be sufficiently relevant as a conceptual and practical tool for assessment of the proposed distribution models (home food delivery models). In the economic dimension, five attributes are defined: “

affordability” as the price offered to consumers; “

distribution of added value” as the feature which concerns the contribution of the SFSC to the local economy as the means of fair distribution of added value and profits between SFSC members; “

economic development” as a measure of SFSC has an impact on strengthening local economies and employment rate; “

efficiency” represented by delivery costs and “

resilience” to the infrastructure disruption, demand disturbance, price deviation and so forth.

The environmental category is covered by the attributes “

pollution” and “

food waste”. The distance driven per order has a strong impact on GHG emissions, so possible effects of various distribution scenarios will be estimated on the basis of the potentially driven distance by using the emission factors defined by relevant literature. A sustainable food system should be based on resource use efficiency in order to minimize its impact on the environment, where the waste has a crucial role [

60]. Food waste in context of SFSC distribution refers to edible food losses and could be defined as food lost at any stage of the SFSC (decrease in food quantity or quality). Reducing food waste in distribution processes could be achieved by using technical innovations and knowledge.

In the social category, the identified attributes are: “customer behavior”, defined by customers’ willingness to pay for such kind of services and their interest in establishing direct connections with the producers; “food security and reliability” defined by accuracy and quality of the delivery services avoiding to receive broken food packages or food; and “labor”, which is already stated as some kind of feature from the economic category but it also concerns the social category regarding all persons who can get the financial benefit from establishing SFSC.

The health dimension is covered by attributes “

food safety” and “

food quality”. Food safety and food quality are two terms which describe aspects of food products and the reputations of the producers [

61], as well as the potential delivery service. Food safety generally could be defined as an ‘assurance that the food will not cause harm to the consumer when it is prepared and/or eaten according to its intended use’ [

61,

62]. In the context of distribution, food safety assumes maintaining the right conditions for food during delivery and timely processing of problems and their control based on respecting appropriate standards. Food quality can be defined as ‘fitness for consumption’ and it is linked to trust/confidence [

61], which could be based on face-to-face relationships or on formal and codified rules with a third-party guarantee [

61]. Hence, food quality in SFSC could be estimated through potential for food traceability and level of trust-based relations between SFSC actors in food quality targeting.

The applied sustainability assessment concept could be categorized as one from integrated assessment group, which are used for supporting decisions related to a policy or a project in a specific region. In the context of sustainability assessment this integrated assessment concepts have an ex-ante focus and often are carried out in the form of scenarios [

63]. The selection of these attributes and indicators was made by the authors, according to the analysis of relevant literature and their own perceptions and experiences, taking into account attributes’ applicability to the researching problem. Further researching steps could be realized towards their confirmation and justification by the stakeholders involved in the examined real SFSC case studies.

4. Discussion

Forming a model of an efficient logistics system is crucial for the development of a sustainable SFSC. In this paper, the abovementioned models include advancement and improvement of logistics resources and competence of producers, using logistic capacities of specialized logistics service providers, or the use of crowdsourcing. Each of those solutions is based on the usage of modern ICT and each of those solutions has its own advantages and disadvantages from the operation and sustainability point of view. The proper design of SFSC should not only involve improved logistics operability but also the satisfactory performance of sustainability [

68]. Hence, the proposed solution that offers the best balance between the value created for the customer, the value captured by the involved companies and the value for the environmental sustainability, will be the most attractive one.

Findings in this study are aligned with literature regarding identification of the main operational problem in the establishment of the first model in the functioning SFSC (Solution 1). That is, a small concentration of cargo flows (small size delivery and small minimal order), could reduce the efficiency in terms of transportation [

8]. As concluded in Reference [

69], this is an expensive mode of delivery, both in terms of time and money, especially in situations of delivery to less populated places, long transportation distances and when specific transportation conditions are required [

21]. On the other hand, this model allows producers greater flexibility and freedom during the transportation process since they can perform other activities (e.g., grocery shopping, having meetings, performing other tasks, etc.). This statement could be confirmed by [

70], where analyzed case study has shown that food deliveries are usually made by own account transport by the food suppliers or producers. Problems of the operational efficiency of the distribution can be solved by forming clusters of producers to share information and knowledge among the members (information integration), to coordinate and share their transport resources, to create joint distribution facilities and joint distribution planning processes (trend towards centralization). Low operational efficiency of Solution 1 impacted on its very low sustainability performances measured by GHG emissions (as proved in Reference [

69]), food waste and ability to provide food at acceptable price for customers. However, as a solution based on zero intermediaries, it has the fairest added value distribution.

Solution 2 implies leaving distribution to specialized logistics providers. In this way, the full integration, coordination and optimization of logistics activities are achieved and manufacturers are focused on their core activities. It is believed that the overall operational efficiency in this model, represented by costs, the service level and user-friendliness of the service will be the best compared to other solutions, as proven in some other cases [

18]. Generally, it could be claimed that the obtained value of cost efficiency for Solution 2, as well as for two other solutions (

Appendix A), are highly realistic in comparison with the values from other research [

25,

71]. In addition, LSP provides full quality of delivery in terms of respect of the conditions in which food is stored and transported. The main disadvantage here is the sustainability and business success dependence on the quality, organization and price of LSP services. Besides this sustainability disadvantage, represented throughout the low value of attribute ‘distribution of added value’, the indicators of all other sustainability attributes have high or medium estimated impact on the sustainability value proposition.

In line with previous literature [

49,

72], third solution is eco- and social-friendly, because it is characterized by a smaller volume of GHG emission per delivery and it gives chances to individuals for extra income. In Solution 3, LSP is excluded, which can have positive financial effects (reducing the costs of delivery). Crowdsourced distribution, if properly implemented, could be a very suitable solution for delivering small packages over short distances. On the other hand, disadvantages of this model are related to the inability of the full flow control of the products, primarily in the context of sanitary and health conditions. Using non-professional staff could lead to the problems of reliability as well as to the problems of trust and liability. However, the implementation of SFSC member rating system could be a very effective solution to these issues.

Selection and implementation of some of those solutions will depend upon an individual case and business conditions. Nevertheless, the results of this research provide a detailed insight for all stakeholders interested in the development of such delivery based SFSCs. It makes food producers aware of various food distribution options and their advantages and disadvantages from the producer’s point of view. For each proposed service, we identify the value propositions and the issues the service aims to address. Regards LSPs, as SFSC operators, it can be inferred that these results could serve for evaluating the new market potential, as well as for evaluating the feasibility of creating appropriate business models. The paper result could help in government’s policy-making in choosing affirmative initiatives and appropriate concept of SFSC development, especially in regions with a low level of SFSC concept maturity.

5. Conclusions

Globalization of food production influences the structure of food supply chains. This impact is mainly reflected in the increasing complexity of food supply chains and in raising distance to which food is transported on its way to consumers, which has a negative impact on the environment, food quality and sustainability of food production. Hence, systems of local food production and distribution have gotten great attention in the last two decades, mostly for the reasons of consumers’ growing motivation to purchase locally produced food, as it is more in line with domestic quality and health standards. However, local food producers cannot be competitive enough with large food supply chains due to low economy of scale and relatively high logistics costs. Because of that, supply chains of the local food products (or short food supply chains) require a corresponding solution in food distribution, which follows modern logistics strategies and approaches in combination with a contemporary ICT solution, with the final aim to ensure their sustainability and to improve overall competitiveness of local food producers. In this paper, several solutions for the improvement of distribution in SFSCs are explored. All of the analyzed solutions are based on digitization of business and logistics processes and involve existence of ICT which would ensure efficient coordination and collaboration of all members of SFSC throughout the development of a form of “digital local food market”. In addition to solving the problems of efficient and sustainable food distribution in SFSCs, the proposed solutions also obey the principle of food identifiability which enables consumers to ensure quality of delivered products. Close to modelling and exploring the proposed solutions in detail, three business process models, which render the sequence and interaction of activities among diversified food distribution scenarios, have been ensued. For each operational scenario, the major advantages and challenges of its practical implementation are revealed. After that, based on the created conceptual framework and selected set of attributes and indicators, a sustainability assessment of the proposed solutions has been accomplished. In the context of sustainability assessment, the applied integrated assessment tool is based on qualitative approach with an ex-ante focus.

Developed business process models could serve as a base for possible development of the appropriate simulation models, as well as business models, that could be identified as the next step, towards further research in this area. Those simulation models, based on real data, could be used for further estimation of delivery operation efficiency and costs for each distribution scenarios, with the final aim of selecting the most sustainable food distribution mode from the economic point of view. The selection and implementation of some of these solutions will depend on the specific case and business factors such are: lot size, lead time, assortment, the risk of purchase error, transaction cost, service support, customization and so forth. Also, the developed framework for sustainability assessment, with proposed attributes and indicators, could serve as a base for development of a robust multi-criteria analysis, which will have the advantage of incorporating both qualitative and quantitative data into the process of sustainability assessment of the proposed solutions in the context of real SFSC.

In this paper, we focused on SFSC which are delivery based, hence distribution and logistics are crucial for producers. Taking this fact into account we have explored and analyzed several potential solutions for SFSC improvement from the aspect of logistics. The obtained analyses results could contribute to better understanding of the issues and challenges in establishing digitized home delivery services and could serve as a help in decision-making for food producers and other involved stakeholders. However, we do not provide a general solution because entering such kind of delivery services is challenging and there is no ‘one size fits all’ approach.