Determinants Linked to Family Business Sustainability in the UAE: An AHP Approach

Abstract

:1. Introduction

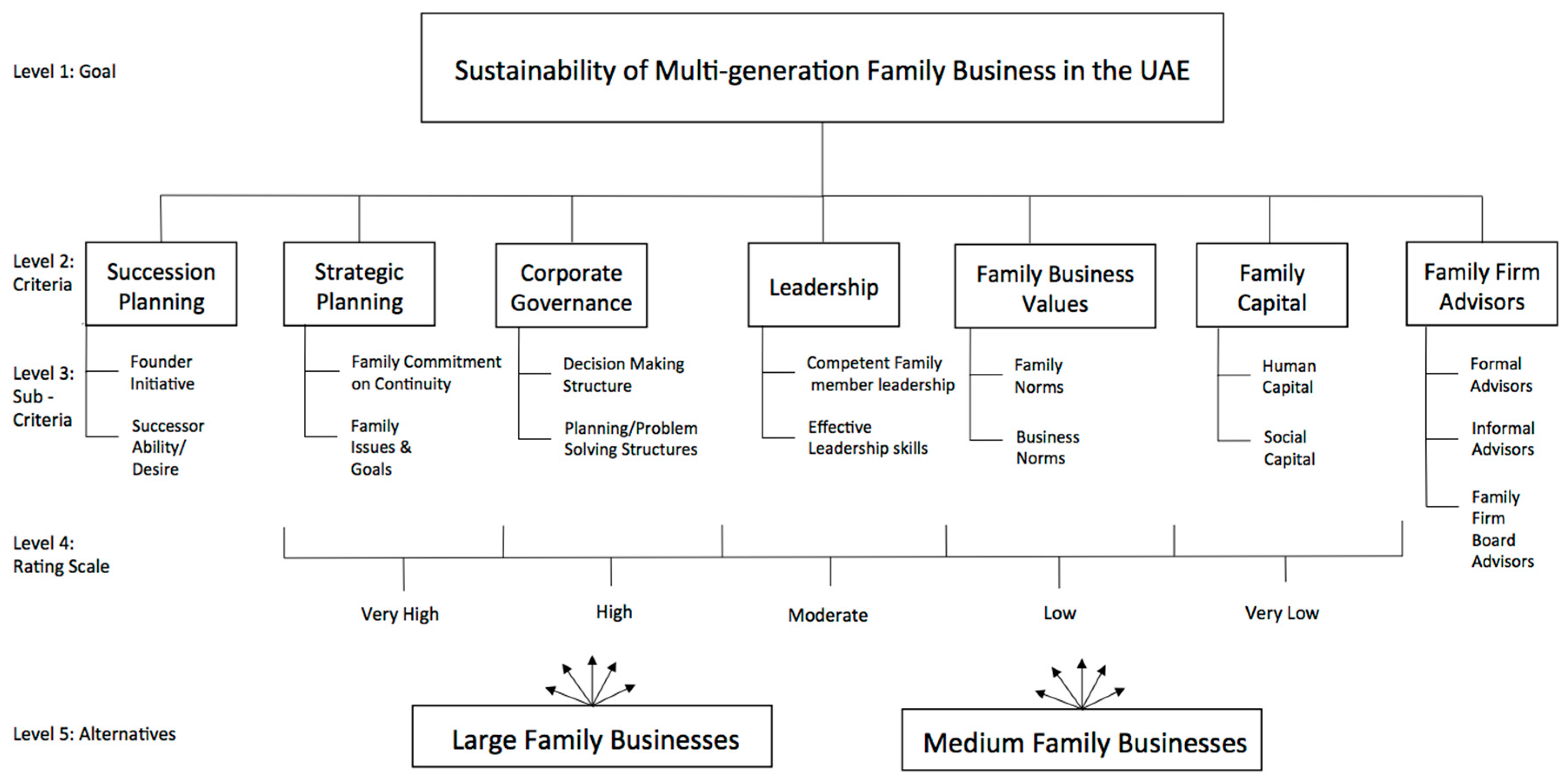

Research Landscape

- (1)

- To identify the factors that influence the viability of a family business; and

- (2)

- To prioritize the importance of factors such as succession planning, strategic planning, corporate governance, leadership, family business values, family capital and role of advisors in two different cases considering large and medium family businesses in the UAE.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Family Business Definitions

2.2. Family Business Developmental Stages

2.3. Family Business and Sustainability

2.4. Success Factors in Family Business Sustainability

2.4.1. Succession Planning

2.4.2. Strategic Planning

2.4.3. Corporate Governance

2.4.4. Leadership

2.4.5. Family Business Values

2.4.6. Family Capital

2.4.7. Family Firm Advisors

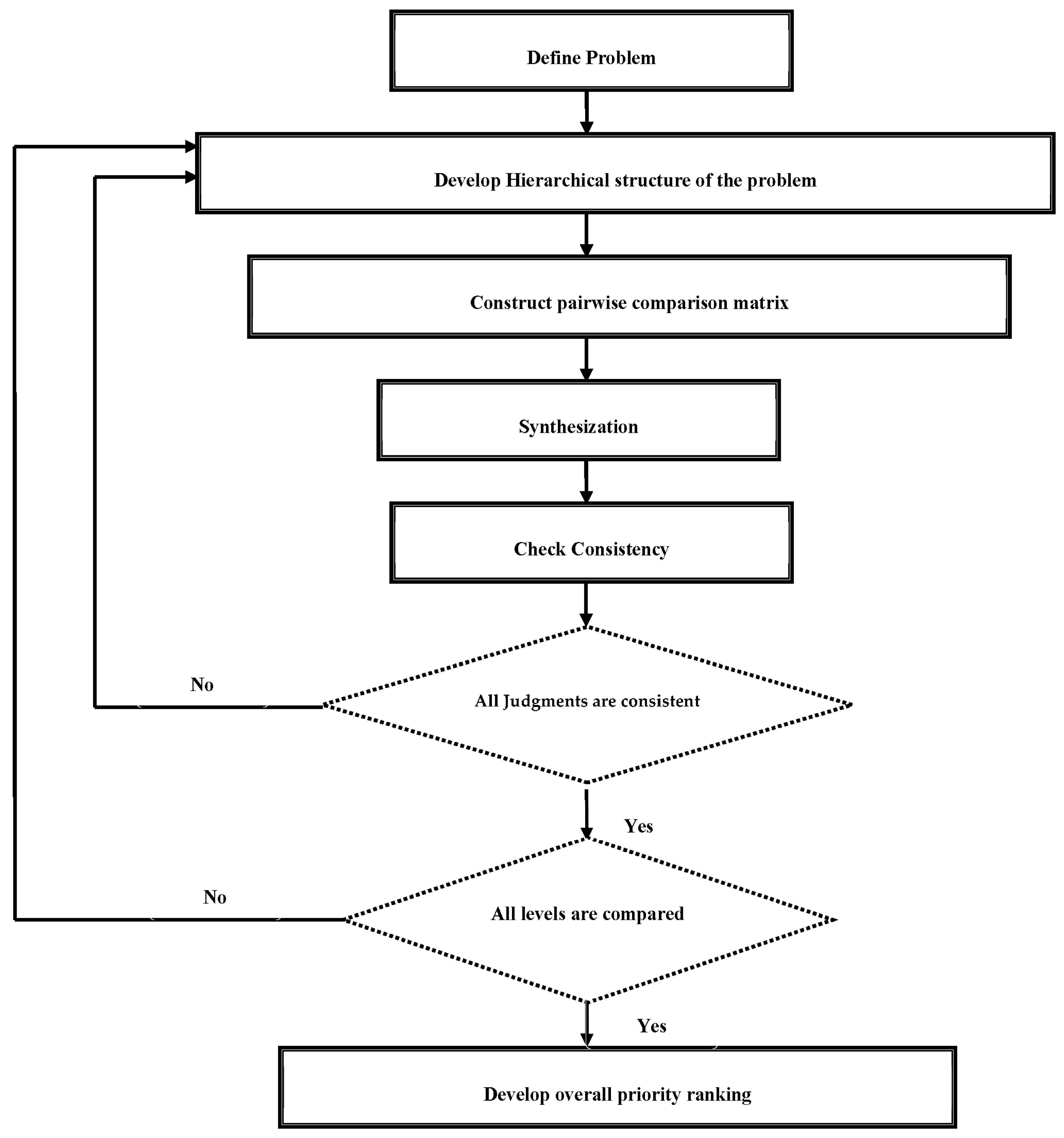

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Technique

3.2. Data Collection and Interview Procedure

- To ensure that the respondent is the right person filling the AHP preference scale.

- For the interviewer to understand how the business is running and how it is led.

- For the interviewer to evaluate the family members’ business knowledge and their preparation for future generations.

3.3. Results

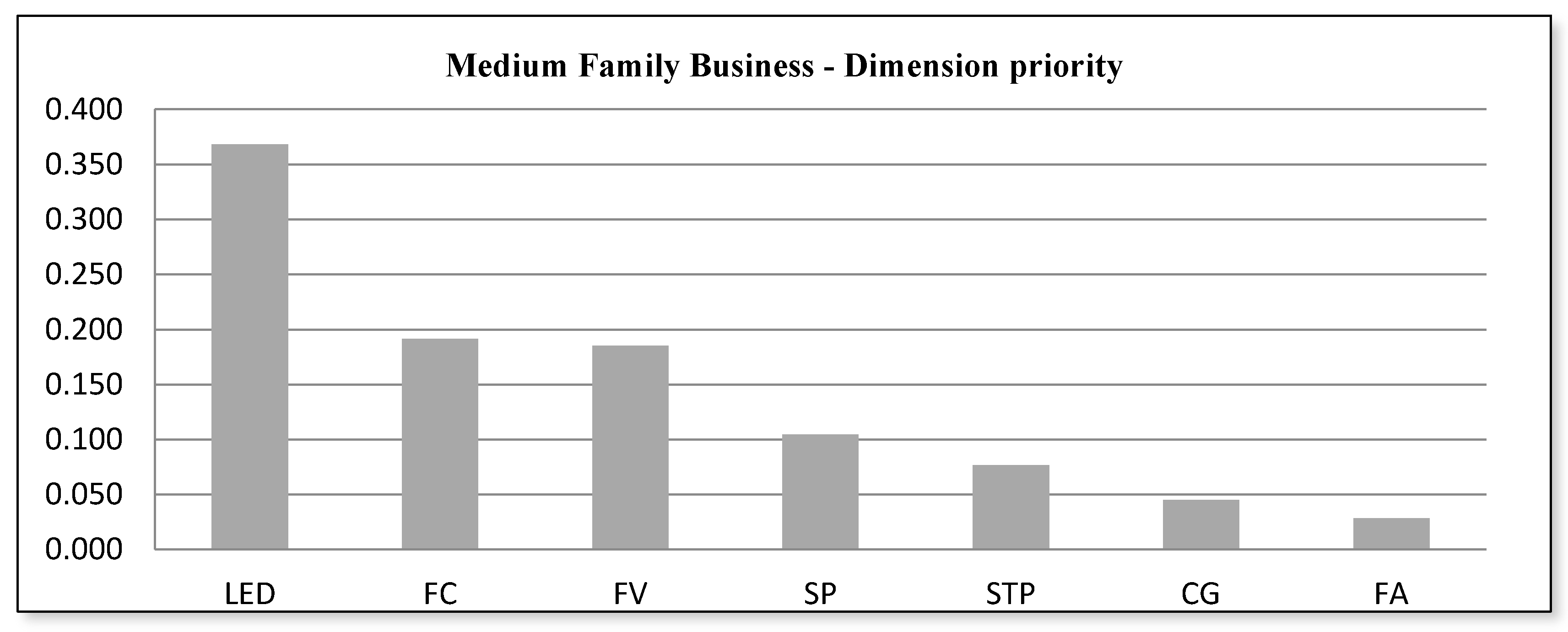

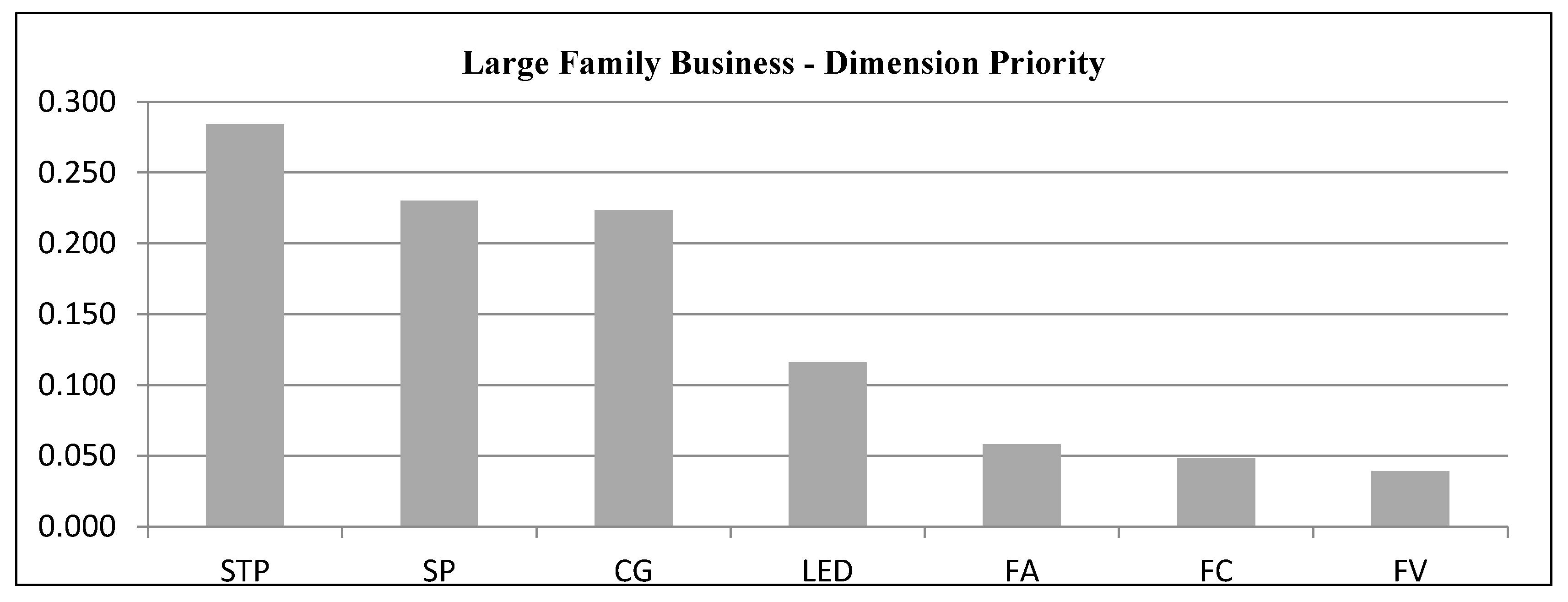

3.3.1. Pairwise Comparison for Main-Criteria

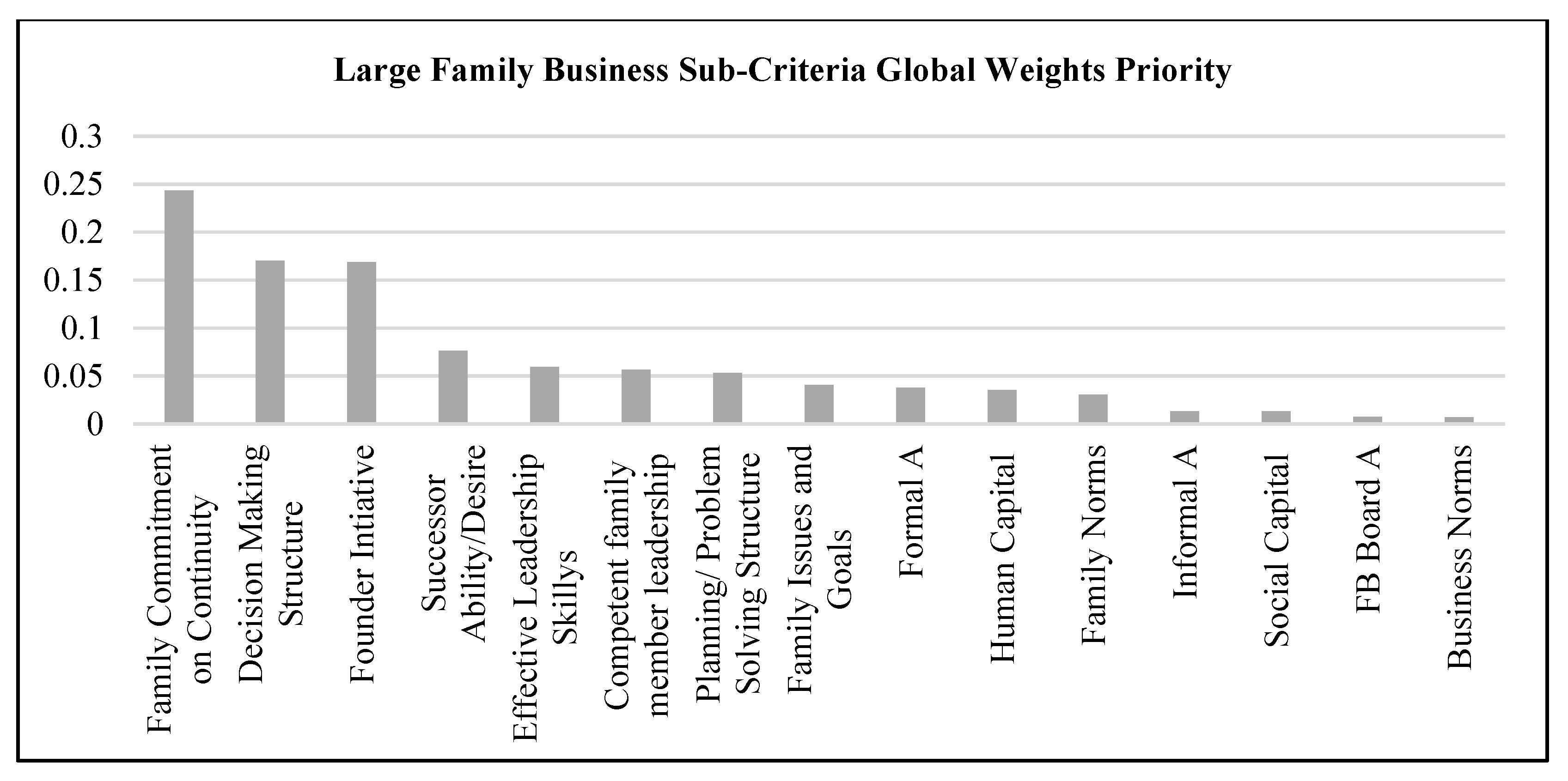

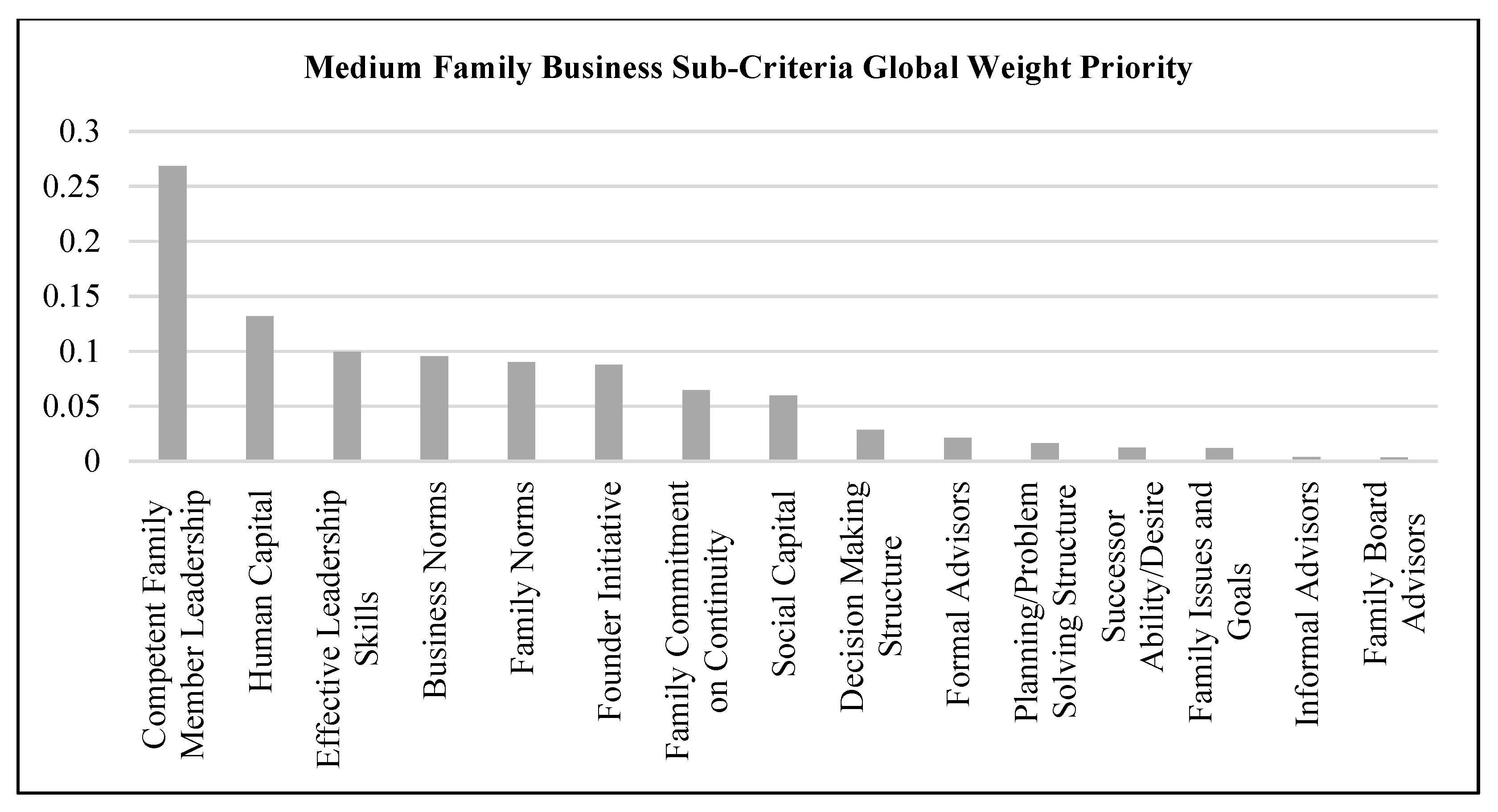

3.3.2. Pairwise Comparison for Sub-Criteria

3.4. Computing Alternatives Global Weights

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Limitations

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zahra, A.; Sharma, P. Family Business Research: A strategic Reflection. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2004, 15, 331–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulze, W.S.; Gedajlovic, E.R. Whither family business? J. Manag. Stud. 2010, 47, 191–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astrachan, J.H. Commentary on the special issue: The emergence of a field. J. Bus. Ventur. 2003, 18, 567–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poza, E.J. Family Business 3E; South-Western Cengage Learning: Mason, OH, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- El Agamy, F.; Schreiber, C. Good Governance in Family Firms: Five Case Studies from the Middle East; Tharwat Family Business Forum and Pearl Initiative: Singapore, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, J. The Family Business in the World Economy; (H. B. School, Interviewer); Hathaway Brown School: Shaker Heights, OH, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Making, S.G. Family Business Governance in the Middle East: The challenges facing the continuity of family businesses in the Middle East. Trust Trust. 2009, 15, 770–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, J. Growing the Family Business: Special Challenges and Best Practices. Fam. Bus. Rev. 1997, 10, 323–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Chrisman, J.; Gersick, K. 25 Years of Family Business Review: Reflections on the past and perspectives for the future. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2012, 25, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aronoff, C.E. Family Business Survival: Understanding the statistics “only 30%”. Fam. Bus. Advis. 1999, 8, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Beckhard, R.; Dyer, W.G. Managing continuity in the family-owned business. Organ. Dyn. 1983, 12, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poza, E.J.; Hanlon, S.; Kishida, R. Does the family business interaction factor represent a resource of a cost? Fam. Bus. Rev. 2004, 17, 99–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tio, J.; Kleiner, B.H. How to be an effective chief executive officer of a family owned business. Manag. Res. News 2005, 28, 142–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, J. Why the 21st Century Will Belong to Family Businesses. 28 March 2016. Available online: https://hbr.org/2016/03/why-the-21st-century-will-belong-to-family-businesses (accessed on 5 August 2017).

- Stamm, I.; Lubinski, C. Crossroads of family business research and firm demography: A critical assessment of family business survival rates. J. Fam. Bus. Strategy 2011, 2, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, R. Family Business: Setting a Benchmark. June 2012. Available online: http://vision.ae/articles/family_business_setting_a_benchmark (accessed on 17 March 2016).

- Sabi, A. The Succession Challenge in GCC Family Business. 14 November 2015. Available online: http://globalriskinsights.com/2015/11/the-succession-challenge-in-gcc-family-businesses/ (accessed on 17 March 2016).

- Pierce, C. What’s Holding Back Family Businesses in the GCC? 29 July 2016. Available online: http://gulfnews.com/business/sme/what-s-holding-back-family-businesses-in-the-gcc-1.1870272 (accessed on 9 August 2017).

- Strike, V.M. Advising the family firm: Reviewing the past to build the future. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2012, 25, 156–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farouk, H. The Rules of Engagement for Family-Owned Businesses. Available online: http://www.grantthornton.ae/page/the-rules-of-engagement-for-family-owned-businesses (accessed on 1 June 2017).

- Gomez, E.T. Inter-Ethnic Relations, Business and Identity: The Chinnese in Britain and Malaysia; United Nations Research Institute for Social Development: Geneva, Switzerland, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- DubaiChamber. Dubai Chamber of Commerce. 2012. Available online: http://web.dubaichamber.ae/LibPublic/Family%20Businesses%20in%20Dubai%20Definition%20Structure%20Performance.pdf (accessed on 23 October 2014).

- Dyer, W.G.; Sanchez, M. Current state of family business theory and practice as reflected in Family Business Review 1988–1997. Fam. Bus. Rev. 1998, 11, 287–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvato, C.; Aldrich, H. That’s interesting! in family business research. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2012, 25, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Chrisman, J.; Chua, J.H. Strategic managment of the family business: Past research and future challenges. Fam. Bus. Rev. 1997, 10, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, J.; Kraus, S.; Filser, M.; Kellermans, F. Mapping the field of family business research: Past trends and future directions. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2015, 11, 113–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korsching, P.F.; Allen, J.C. Locality based entrepreneurship: A strategy for cummunity economic vitality. Community Dev. J. 2004, 39, 385–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, P.D.; Zuiker, V.S.; Danes, S.M.; Stafford, K.; Heck, R.K.; Duncan, K.A. The impact of the family and business on family business sustainability. J. Bus. Ventur. 2003, 18, 639–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P. An Overview of the field of Family Business Studies: Currect Status and DIrections for the Future. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2004, 17, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stafford, K.; Bhargava, V.; Danes, S.; Haynes, G.; Brewton, K. Factors associated with long-term survival of family business: Duration analysis. J. Fam. Econ. 2010, 31, 442–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saaty, T. The Analytical Hierarchy Process; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Wrotman, M.S. Critical Issues in Family Business: An International Perspective and Research. In Proceedings of the ICSB 40th World Conference, Sydney, Australia, 18–21 June 1995; pp. 53–76. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, J. Definitions and Typologies of the Family Business; Harvard Business School: Boston, MA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Rettab, B.; Fakhr, T.A.; Morada, M.P. Family Businesses in Dubai: Definition, Structure Performance; Data Management and Research Department; Dubai Chamber of Commerce and Industry: Rigga Al Buteen, Dubai, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Centre Abu Dhabi. Statistics of Micro, Small, Medium and Large Enterprises. 2013. Available online: https://www.scad.ae/Release%20Documents/SME%202013%20Report%20-%20En.pdf (accessed on 6 December 2017).

- Gersick, K.; Davis, J.; Hampton, M.; Lansberg, I. Generation to Generation: Life Cycle of Family Business; Harvard Business School: Boston, MA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Abu Dhabi Events Calender. 45th National Day Celebrations. 2016. Available online: https://abudhabievents.ae/en/Pages/45th-national-day-celebrations.aspx (accessed on 10 December 2016).

- Augustine, B.D. Middle East’s Family Businesses Get Serious on Sustainability. 7 November 2015. Available online: http://gulfnews.com/business/money/middle-east-s-family-businesses-get-serious-on-sustainability-1.1614502 (accessed on 10 December 2016).

- World Commission on Enviroment and Development. Our Common Future the Brundland Report; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Ward, J. Keeping the Family Business Healthy: How to Plan for Continuing Growth, Profitability, and Family Leadership; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Lambrecht, J.; Lievens, J. Pruning the Family Tree: An unexplored path to family business continuity and family harmony. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2008, 4, 295–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gameno Sandig, A.G.; Labadie, G.J.; Saris, W.; Mayordomo, X.M. Internal factors of family business performance: An integrated theoretical model. In Handbook of Research on Family Business; Poutzioris, P.Z., Smyrnios, K.X., Klein, S.B., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing Limited: Cheltenham, UK, 2006; pp. 145–164. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, P.; Chua, J.; Chrisman, J. Perceptions about the extent of succession planning in Canadian family firms. Can. J. Adm. Sci. 2000, 17, 233–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Chrisman, J.J.; Chua, J.H. Predictors of satisfaction with the succession process in family firms. J. Bus. Ventur. 2003, 18, 667–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumentritt, T.; Mathews, T.; Marchisio, G. Game theory and family business succession: An introduction. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2013, 26, 51–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Massis, A.; Chua, J.H.; Chrisman, J.J. Factors preventing intra-family succession. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2008, 21, 183–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, C. Management Succession in Small and Growing Enterprises; Harvard Business School: Boston, MA, USA, 1953. [Google Scholar]

- Trow, D. Executive succession in small Companies. Adm. Sci. Q. 1961, 6, 228–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delmas, A.M.; Gergaud, O. Sustainabile Certification for Future Generations: The Case of Family Business. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2014, 27, 228–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Writer, S. Governance, Succession Issues Still Hound GCCC Family Firms. 22 April 2017. Available online: http://www.arabianbusiness.com/governance-succession-issues-still-hound-gcc-family-firms--671120.html (accessed on 15 August 2017).

- Sharma, P.; Chrisman, J.; Chua, J. Succession Planning as Planned Behavior: Some Empirical Results. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2003, 16, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, J. The special role of strategic Planning for family businesses. Fam. Bus. Rev. 1988, 1, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astrachan, J.H.; Kolenko, T.A. A neglected factor explaining family business success: Human resource practices. Fam. Bus. Rev. 1994, 7, 251–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumentritt, T. The relationship between boards and planning in family businesses. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2006, 19, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlock, R.; Ward, J. Strategic Planning for the Family Business; Palgrave: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, G.; Scholes, K.; Wittington, R. Exploring Corporate Strategy Text and Cases, 7th ed.; Pearson Edutcation Limited: Harlow, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Eddleston, K.A.; Kellermanns, F.W.; Floyd, S.W.; Crittenden, V.L.; Crittenden, W.F. Planning for growth: Life stage differences in family firms. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2013, 37, 1177–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price Waterhouse Coopers (PWC) (2016). Addressing the “Missing Middle”: Strategic Planning. Available online: https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/services/family-business/family-business-survey-2016/strategic-planning.html (accessed on 9 August 2017).

- Aronoff, C.; Ward, J. Family Business Values: How to Assure a Legacy of Continuity and Success; Business Owner Resources: Marietta, GA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Pieper, T.M. Corporate Governance in Family Firms: A Literature Review; INSEAD Initiative for Family Enterprise: Fontaineblea, France, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Ward, J.L. Good governance is different for family firms. Fam. Bus. 2003, 84–85. Available online: https://www.scholars.northwestern.edu/en/publications/good-governance-is-different-for-family-firms (accessed on 17 January 2018).

- Lansberg, I. Succeeding Generations; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenblatt, P.C.; De Mik, L.; Anderson, R.M.; Johnson, P.A. The Family in Business; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Mustakallio, M.; Autio, E.; Zahra, S.A. Relational and contractual governance in family firms: Effects on strategic decision making. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2002, 15, 205–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astrachan, J.H.; Klien, S.B.; Smyrnios, K.X. The F-PEC scale of family influence: A proposal for solving the family business definition problem. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2002, 15, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiedler, F.E. Research on leadership selection and training: One view of the future. Adm. Sci. Q. 1996, 41, 241–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Westhuizen, J.; Garnett, A. The correlation of leadership practices of first and second generation family business owners to business performance. Medterranean J. Soc. Sci. 2014, 5, 323–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yukl, G. Leadership in Organizations; Pearson Education; Prentice Hall Inc.: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Le Breton-Miller, I.; Miller, D.; Steier, L.P. Toward an integrative model of effective FOB succession. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2004, 28, 305–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lansberg, I. The succession conspiracy. In Family Business Sourcebook II; Anroff, C.E., Astrachan, J.H., Ward, J.L., Eds.; Business Owner Resources: Marietta, GA, USA, 1988; pp. 70–86. [Google Scholar]

- Cater, J.J.; Justis, R.T. The development and implementation of shared leadership in multi-generational family firms. Manag. Res. Rev. 2010, 33, 563–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyck, B.; Mauws, M.; Strake, F.A.; Mischle, G.A. Passing the baton: The importane of sequence, timing, technique and communication in executive sucession. J. Bus. Ventur. 2002, 17, 143–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartel, E.C.; Bozer, G.; Levin, L. Family business leadership transition: How an adaption of executive coaching may help. J. Manag. Organ. 2009, 15, 278–391. [Google Scholar]

- Tapies, J.; Moya, M.F. Values and Longevity in family business: Evidence from a cross-cultural analysis. J. Fam. Bus. Manag. 2012, 2, 130–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koiranen, M. Over 100 years of age but still entrepreneurially active in business: Exploring the values and family characteristics of old Finnish family firms. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2002, 15, 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lansberg, I.S. Managing human resources in family firms: The problem of institutional overlap. Organ. Dyn. 1983, 12, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdem, F.; Baser, G.G. Family and business values of reginal family firms: A qualitative research. Int. J. Islam. Middle Eastern Financ. Manag. 2010, 3, 47–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D.; Le Breton-Miller, I. Managing for the Long Run: Lessons in Competitive Advantage from Great Family Businesses; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Danes, S.; Lee, J.; Stafford, K.; Heck, R. The effects of ethnicity, families and culture on entrepreneurial experience: An extension of Sustainable Family Business Theory. J. Dev. Entrep. 2008, 13, 2229–2268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danes, S.; Stafford, K.; Haynes, G.; Amarapurkar, S. Family Capital of Family Firms, Bridging Human, Social and Financial Capital. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2009, 22, 199–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portes, A. Social Capital: Its Orgins and applications in modern Socilogy. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 1998, 24, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, J.; Hoelscher, M.; Sorenson, R. Achieving sustained competitive advantage: A family capital theory. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2006, 19, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirmon, D.G.; Hitt, M.A. Managing resources: Linking unique resources, management, and wealth creation in family firms. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2003, 27, 339–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavrou, E.T. Succession in family businesses: Exploring the effects of demographic factors on offspring intentions to join and take over the business. J. Small Bus. Manag. 1999, 37, 43–61. [Google Scholar]

- Alder, S.; Kwon, S. Social Capital: Prospects for a new concept. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2002, 27, 17–40. [Google Scholar]

- Sorenson, R.L.; Bierman, L. Family capital, family business, free enterprise. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2009, 22, 193–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astrachan, J.H.; McMillan, K.S. Handbook of Family Business Family Business Consultation: A Global Perspective; Kaslow, F.W., Ed.; International Business Press: Binghamton, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 347–363. [Google Scholar]

- Craig, J.B.; Moores, K. Championing family business issues to influence public policy: Evidence from Australia. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2010, 23, 170–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaChapelle, K.; Barnes, L.B. The trust catalyst in family-owned businesses. Fam. Bus. Rev. 1998, 11, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaye, K.; Hamilton, S. Roles of trust in consulting to financial famlies. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2004, 17, 151–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bork, D.; Jaffe, D.; Lane, S.; Dashew, L.; Heilser, Q. Working with Family Businesses; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Hilburt-Davis, J.; Dyer, W.G. Consulting to Family Businesses: A Practical Guide to Contracting, Assessment and Implementation; Jossey-Bass/Pfeiffer: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Le Breton Miller, I.; Miller, D. Agency vs. stewardship in public family firms: Social embeddedness reconciliation. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2009, 33, 1169–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reay, T.; Pearson, A.; Dyer, W. Advising Family Enterprise: Examining the Role of Family Firm Advisors. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2013, 29, 209–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, K.S.; Chiu, S.; Tummala, V. An evaluation of success factors using AHP to implement ISO 14001-based ESM. Int. J. Qual. Reliab. Manag. 1999, 16, 341–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alessio, I.; Craig, P.; Philippe, N. AHPSort: An AHP-based method for sorting problems. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2012, 50, 4767–4784. [Google Scholar]

- Hussain, M.; Ajmal, M.M.; Khan, M.; Hussein, S. Competitive Priorities and Knowledge Management: An Empirical Investigation of Manufacturing Companies in UAE. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2015, 26, 791–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, M.; Malik, M.; Al Neyadi, H.S. AHP framework to assist lean deployment in Abu Dhabi public healthcare delivery system. Bus. Process Manag. J. 2016, 22, 546–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlDhaheri, R.; Jabeen, F.; Hussain, M.; Abu-Rahma, A. Career choice of females in the private sector: Empirical evidence from the United Arab Emirates. Higher Educ. Skills Work-Based Learn. 2017, 7, 179–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saaty, T.L.; Vargas, L.G. Models, Methods, Concepts Applications of the Analytic Hiererchy Process; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Boston, MA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Saaty, T.L. How to make a decision: The analytic hierarchy process. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 1990, 48, 9–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saaty, T.L. Decision Making for Leaders: The Analytic Hierarchy Process for Decisions in a Complex World; RWS Publications: Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Stake, R. The Art of Case Study Research; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1995; p. 57. [Google Scholar]

- Neubauer, H. The dynamics of succession in family business in western European countries. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2003, 16, 269–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchloz, B.; Crane, M.; Nager, R. The Family Business Answer Book; Prentice Hall Press: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Sarbah, A.; Xio, W. Good Corporate Governance Structures: A must for Family businesses. J. Bus. Manag. 2015, 3, 40–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G. Culture’s Consequences: International Differences in Work-Related Values; Sage Publications, Inc.: Beverly Hills, CA, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

| Enterprise Category | Number of Employees |

|---|---|

| Micro | <5 |

| Small | 5–19 |

| Medium | 20–49 |

| Large | ≥50 |

| Phase | Older Generation | Younger Generation | Approximate Business Age | Generation Leading |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Young Family Business | >40 years old | If present <18 years old | <15 years | First Generation |

| Independence of younger generation entering the family business | 33 to 55 years old | 13 to 29 years old | <30 years | First Generation |

| Working Together | 50 to 65 years | 20 to 45 years | <45 years | First and Second Generation leading |

| Passing the baton | Older than 60 years old | >45 years | Second Generation leading |

| Criteria | Sub-Criteria | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Succession Planning | Founder Initiative Successor Ability/Desire | Christensen (1953), Trow (1961), Ward (1987), Delmas and Gergaud (2014), Writer (2017), Sharma et al. (2003a), Sharma et al. (2003b) |

| 2 | Strategic Planning | Family Commitment on Continuity Family Issues and Goals | Astrachan and Kolenko (1994), Blumentritt (2006), Carlock and Ward (2001), Ward (1988), Price Waterhouse Coopers (PWC) (2016), Ward (1988) |

| 3 | Corporate Governance | Decision Making Structure Planning/Problem Solving Structure | Lansberg (1999), Mustakallio, Autio, and Zahra (2002), Pieper (2003), Aronoff (2004), Carlock and Ward (2001) |

| 4 | Leadership | Competent Family Member Leadership Effective Leadership Skills | Fiedler (1996), Gersick et al. (1997), Hartel, Bozer, and Levin (2009), Van der Westhuizen and Garnett (2014), Le Breton-Miller, Miller, and Steier (2004), Lansberg (1988) |

| 5 | Family Business Values | Family Norms Business Norms | Aronoff and Ward (2000), Erdem and Baser (2010), Tapies and Moya (2012), Lansberg (1983), Koiranen (2002) |

| 6 | Family Capital | Human Capital Social Capital | Danes, Lee, Stafford, and Heck, (2008), Danes, Stafford, Haynes, and Amarapurkar (2009), Stafford et al. (2010), Sirmon and Hitt (2003), Danes et al. (2009) |

| 7 | Family Firm Advisors | Formal Advisors Informal Advisors Family Firm Board Advisors | LaChapelle and Barnes (1998), Kaye and Hamilton (2004), Astrachan and McMillan (2006), Strike (2012) |

| Intensity of Importance | Definition | Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Equal importance | Two criteria contribute equally to the objective |

| 3 | Moderate importance | Judgement slightly favours one over another |

| 5 | Strong importance | Judgement strongly favours one over another |

| 6 | Very strong importance | A criterion is strongly favoured and its dominance is demonstrated in practice |

| 9 | Absolute importance | Importance of one over another affirmed on the highest possible order |

| 2,4,6,8 | Intermediate values | Used to represent compromise between the priorities listed above |

| Order of the Matrix | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | |

| RI Value | 0 | 0 | 0.58 | 0.90 | 1.12 | 1.24 | 1.32 | 1.41 | 1.45 | 1.49 | 1.51 | 1.48 | 1.56 | 1.57 | 1.59 |

| L1 | L2 | L3 | L4 | L5 | L6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Industry | Diversified (e.g., Retail, Real Estate, Construction, Oil Field Services, etc.) | Diversified (e.g., Automotive, Oil and Gas, Contracting, Commercial, Marine Engineering, etc.) | Construction | Retail of large Swiss Watches Brand | Manufacturing (Ready Mix Concrete) | Diversified (e.g., Hospitality, Real Estate, Automotive, Travel, and Future Projects) |

| Year established | 1977 | 1979 | 1970 | 1950 | 1972 | 1962 |

| Ownership | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% |

| Managing generation | First/Second | Second | First/Second | Second/Third | First/Second | Family Supervisory board First and Second |

| No. of Family members In the business | 7 | 8 | 3 | 9 | 3 | 9 |

| Interviewee | Son (Chief Executive Officer) | Son (Managing Director) | Daughter (Projects Director) | Son (Chairman) | Father (Chairman) | Second (Supervisory Board Member) |

| Strategic Decision | Father (Chairman) | Family council, board of directors | Father (Chairman) | Family council, board of directors | Father (Chairman) | Family Supervisory board |

| M1 | M2 | M3 | M4 | M5 | M6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Industry | Construction | Manufacturing (Aluminium and Carpentry) | Consultancy | Piling (Construction) | Construction | Dental |

| Year established | 1994 | 1996 | 1981 | 1989 | 1998 | 2000 |

| Ownership | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% |

| Manging generation | First/Second | First/Second | First/Second | First | First | First (Two founder brothers) |

| No. of family members in the business | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Interviewee | Father (Chairman) | Son (General Manager) | Daughter (Design Manager) | Father (Managing Director) | Father (Chairman) | One founder brother (Head Orthodontist) |

| Strategic Decision | Father (Chairman) | Father (Chairman) | Father (Chairman) | Father (Managing Director) | Father (Chairman) | Two founder brothers (Head Orthodontist and Head of dental surgery) |

| Medium Family Business—Pairwise Comparison | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SP | STP | CG | LED | FV | FC | FA | W (Priority) | |

| SP | 1.00 | 3.67 | 3.67 | 0.15 | 0.23 | 0.20 | 4.33 | 0.105 |

| STP | 0.27 | 1.00 | 3.33 | 0.17 | 0.25 | 0.20 | 5.00 | 0.077 |

| CG | 0.27 | 0.30 | 1.00 | 0.17 | 0.22 | 0.22 | 2.67 | 0.045 |

| LED | 6.61 | 5.94 | 5.76 | 1.00 | 2.33 | 3.00 | 6.67 | 0.368 |

| FV | 4.26 | 0.30 | 4.54 | 0.43 | 1.00 | 1.89 | 5.33 | 0.185 |

| FC | 5.05 | 3.97 | 4.54 | 0.33 | 0.53 | 1.00 | 6.33 | 0.192 |

| FA | 0.23 | 0.20 | 0.38 | 0.15 | 0.19 | 0.16 | 1.00 | 0.029 |

| Sum | 17.69 | 15.38 | 23.22 | 2.41 | 4.76 | 6.66 | 31.33 | 1.000 |

| CR | ||||||||

| 0.09 | ||||||||

| Large Family Business—Pairwise Comparison | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SP | STP | CG | LED | FV | FC | FA | W (Priority) | |

| SP | 1.00 | 0.98 | 0.72 | 3.67 | 5.33 | 4.56 | 5.00 | 0.230 |

| STP | 1.02 | 1.00 | 2.78 | 3.67 | 5.67 | 4.33 | 4.67 | 0.284 |

| CG | 1.38 | 0.36 | 1.00 | 4.67 | 6.00 | 3.89 | 3.67 | 0.223 |

| LED | 0.27 | 0.27 | 0.21 | 1.00 | 4.33 | 4.00 | 3.67 | 0.116 |

| FV | 0.19 | 0.36 | 0.17 | 0.23 | 1.00 | 0.49 | 0.31 | 0.039 |

| FC | 0.22 | 0.18 | 0.26 | 0.25 | 2.05 | 1.00 | 0.85 | 0.049 |

| FA | 0.20 | 0.21 | 0.27 | 0.27 | 3.20 | 1.17 | 1.00 | 0.058 |

| Sum | 4.28 | 3.36 | 5.41 | 13.75 | 27.59 | 19.44 | 19.16 | 1.000 |

| CR | ||||||||

| 0.093 | ||||||||

| Large Family Business | Medium Family Business | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Founder Initiative | Successor Ability/Desire | W (Priority) | Founder Initiative | Successor Ability/Desire | W (Priority) | |

| Founder Initiative | 1.0 | 2.72 | 0.731 | 1.0 | 5.22 | 0.839 |

| Successor Ability/Desire | 0.37 | 1.0 | 0.269 | 0.19 | 1.0 | 0.161 |

| Sum | 1.37 | 3.72 | 1.0 | 1.19 | 6.22 | 1.0 |

| Large Family Business | Medium Family Business | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family Commitment on Continuity | Family Issues and Goals | W (Priority) | Family Commitment on Continuity | Family Issues and Goals | W (Priority) | |

| Family Commitment on Continuity | 1.0 | 6.0 | 0.857 | 1.0 | 5.53 | 0.847 |

| Family Issues and Goals | 0.17 | 1.0 | 0.143 | 0.18 | 1.0 | 0.153 |

| Sum | 1.17 | 7.0 | 1.0 | 1.18 | 6.53 | 1.0 |

| Large Family Business | Medium Family Business | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Decision Making Structure | Planning/Problem Solving Structure | W (Priority) | Decision Making Structure | Planning/Problem Solving Structure | W (Priority) | |

| Decision Making Structure | 1.0 | 3.2 | 0.762 | 1.0 | 1.76 | 0.637 |

| Planning/Problem Solving Structure | 0.31 | 1.0 | 0.238 | 0.57 | 1.0 | 0.363 |

| Sum | 1.31 | 4.2 | 1.0 | 1.57 | 2.76 | 1.0 |

| Large Family Business | Medium Family Business | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Competent Family Member Leadership | Effective Leadership Skills | W (Priority) | Competent Family Member Leadership | Effective Leadership Skills | W (Priority) | |

| Competent Family Member Leadership | 1.0 | 0.96 | 0.489 | 1.0 | 2.75 | 0.733 |

| Effective Leadership Skills | 1.05 | 1.0 | 0.511 | 0.36 | 1.0 | 0.267 |

| Sum | 2.05 | 1.96 | 1.0 | 1.36 | 3.75 | 1.0 |

| Large Family Business | Medium Family Business | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family Norms | Business Norms | W (Priority) | Family Norms | Business Norms | W (Priority) | |

| Family Norms | 1.0 | 4.56 | 0.774 | 1.0 | 0.95 | 0.486 |

| Business Norms | 0.22 | 1.0 | 0.180 | 1.06 | 1.0 | 0.514 |

| Sum | 1.22 | 5.56 | 1.0 | 2.06 | 1.95 | 1.0 |

| Large Family Business | Medium Family Business | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human Capital | Social Capital | W (Priority) | Human Capital | Social Capital | W (Priority) | |

| Human Capital | 1.0 | 2.7 | 0.731 | 1.0 | 2.2 | 0.688 |

| Social Capital | 0.37 | 1.0 | 0.269 | 0.45 | 1.0 | 0.313 |

| Sum | 1.37 | 3.72 | 1.0 | 1.45 | 3.2 | 1.0 |

| Large Family Business | Medium Family Business | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Formal Advisors | Informal Advisors | Family Board Advisors | W (Priority) | Formal Advisors | Informal Advisors | Family Board Advisors | W (Priority) | |

| Formal Advisors | 1.0 | 4.22 | 3.67 | 0.648 | 1.0 | 5.53 | 6.33 | 0.743 |

| Informal Advisors | 0.24 | 1.0 | 2.44 | 0.227 | 0.18 | 1.0 | 1.15 | 0.134 |

| Family Board Advisors | 0.24 | 0.41 | 1.0 | 0.125 | 0.18 | 0.87 | 1.0 | 0.123 |

| Sum | 1.47 | 5.63 | 7.11 | 1.0 | 1.36 | 7.41 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| CR | CR = 0.05 < 0.1 | CR = 0.04 < 0.1 | ||||||

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Oudah, M.; Jabeen, F.; Dixon, C. Determinants Linked to Family Business Sustainability in the UAE: An AHP Approach. Sustainability 2018, 10, 246. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10010246

Oudah M, Jabeen F, Dixon C. Determinants Linked to Family Business Sustainability in the UAE: An AHP Approach. Sustainability. 2018; 10(1):246. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10010246

Chicago/Turabian StyleOudah, Mohammed, Fauzia Jabeen, and Christopher Dixon. 2018. "Determinants Linked to Family Business Sustainability in the UAE: An AHP Approach" Sustainability 10, no. 1: 246. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10010246

APA StyleOudah, M., Jabeen, F., & Dixon, C. (2018). Determinants Linked to Family Business Sustainability in the UAE: An AHP Approach. Sustainability, 10(1), 246. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10010246