The Realities of Community Based Natural Resource Management and Biodiversity Conservation in Sub-Saharan Africa

Abstract

:1. Summary

2. Historical Background

2.1. Co-Evolution of Man and Wildlife in Sub-Saharan Africa

2.2. Colonialism and Post-Colonial Conservation and Its Impact on Traditional Management Systems

| SPECIES | DATE | ESTIMATE |

|---|---|---|

| African Elephant (Loxodonta africana) | ||

| 1920s | 120 |

| 1900 | < 4,000 |

| 1900 | 300 |

| White Rhino (Ceratotherium simum) | 1895 | 20 |

| Cape Mountain Zebra ( Equus zebra zebra) | 1922 | 400 |

| Bontebok ( Damaliscus dorcas dorcas) | 1927 | 120 |

| Black Wildebeest ( Connochaetes gnou) | 1890 | 550 |

| WILDLIFE RESOURCE | DATE | SOURCE | QUANTITY EXPORTED | DESTINATION | SOURCE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ivory | 1608–1612 | Mostly West Africa | 23,000 kg/yr | Holland | [47] |

| Ivory | 1909–1917 | Sangha Basin, French Equatorial Africa | 2,694–6,625 kg/yr | France/Europe | [48] |

| Ivory | 1903–1911 | Tanzania | 28,444 kg/yr representing 1,200–1,500 elephants/yr | Germany/Europe | [49] |

| Rhino Horn | 1903–1911 | Tanzania | 5,889 kg/yr representing 2,000–2,300 rhino/yr | Germany/Europe | [49] |

| Duiker Skins | 1950 | Sub-Saharan Francophone Africa | 2 million/yr | France/Europe | [44] |

| Dik-dik Skins (Madoqua sp. & Rhynchotragus sp.) | Mid-20th Century | Somaliland | 350,000/yr | Europe | [50] |

2.3. The Coming of Game Laws, Parks and Reserves

2.4. Parks and Protected Areas in the 20th & 21st Century

- The forced removal of 500 people from the Gombe Stream Chimpanzee Sanctuary, just north of Kigoma on the shores of Lake Tanganyika.

- The Mbulu Game Reserve, Tanganyika, containing 10,000 people, their settlements and 1,000s of acres of grazing land.

- The Katawi and Sabi River Game Reserves, Tanganyika where the removal of people was required.

- The Serengeti Game Reserve, in which the Maasai lost 83% of their former land area.

- The Selous Game Reserve (SGR) from which 40,000 people were moved.

- The Budonga Game Reserve by Lake Albert, Uganda, from which people were eventually removed to protect them from tsetse fly and to encourage the proliferation of wildlife over the 12,950 km2 (5,000 mi2) reserve [43].

- Banned them from using their water boreholes,

- Refused to issue a single permit to hunt on their land,

- Arrested more than 50 Bushmen for hunting to feed their families,

- Banned them from taking their small herds of goats back to the reserve.

3. CBNRM, an Attempt to Mitigate the Past

3.1. Community Based Natural Resource Management (CBNRM)

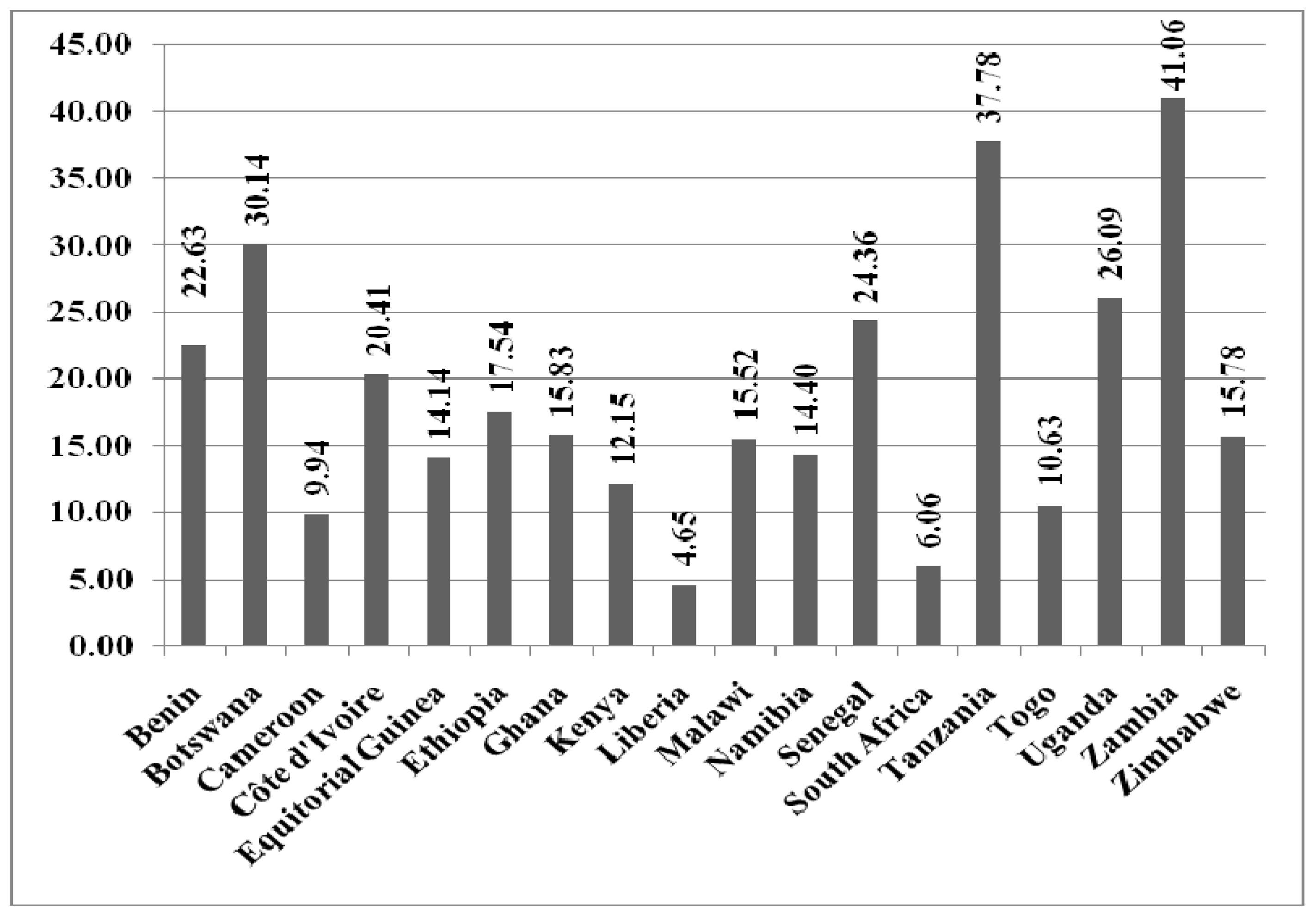

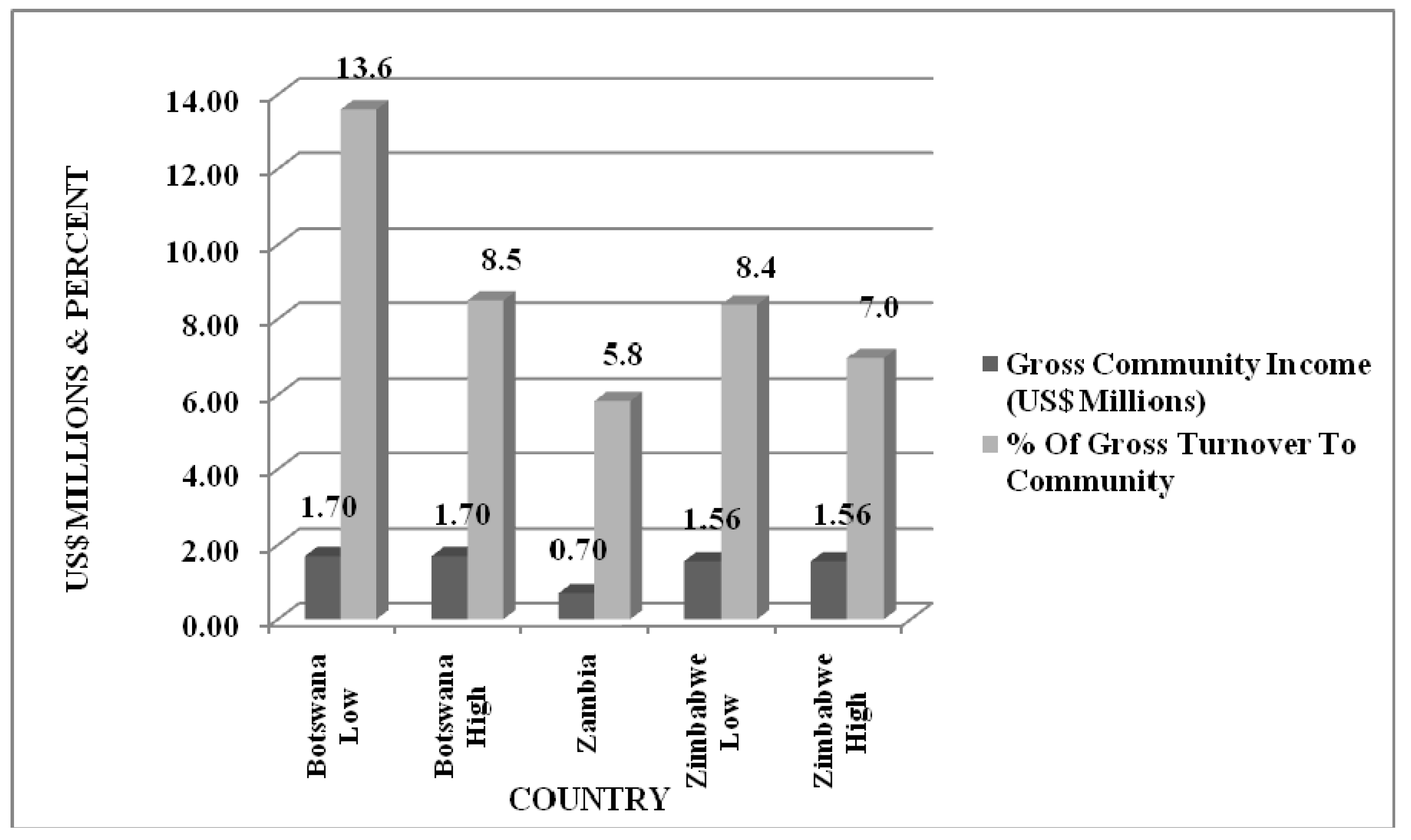

3.2. Economics of CBNRM, a Major Shortcoming

| Country | Annual Value (US$) | Employment (1999) | Annual Community Benefits (US$) | Annual Community Benefits Per Household (US$) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Botswana | Gross US$ 12.5–20 million from trophy hunting, | >1,000 | 1,696,272.00 gross in 1999 8.5%–13.6% of gross turnover | Sankuyu Community: Ngamiland (ND) Area 34, 1996-2001: 22-50 households: US$ 1,190–9,577 gross Khwai, Ngamiland Area 18, 2000–2002: 35-50 households: US$ 4,536–6,480 gross Okavango Community Trust: ND 22 & 23, 2000-2004: 300–500 households: US$ 800–1,333 gross |

| Namibia | >US$ 42 million gross from trophy & biltong hunting, venison and live sales in 1999 >US$ 4.7–5 million gross from trophy hunting (11%–12% of gross) in 1999 | 2,125 directly employed in hunting industry 900 directly employed in allied industries | Mostly on private farms but increasingly on communal conservancies: Nyae Nyae: average US$ 48,415/year gross | Nyae Nyae Conservancy, 1997–2002: 400 households: US$ 79 gross 1998 to 2002, 196 gross in 2003 Torra Conservancy, 2002: 120 households, US$ 853 grossviii, US$ 363 net for household & community projects: Trophy hunting + Lodge |

| South Africa | Gross of US$ 38,395-39 million from overseas trophy hunting in 1999. US$ 140-464 million gross from tourist hunting, taxidermy, live sales, biltong hunting & venison market | 5,000–6,000 jobs from foreign hunting 63,000 jobs On Game Farms | Negligible, 99% hunting on private white owned farms | |

| Tanzania | Grosses of from US$ 27–39 million/year | Selous Conservation Program, 1990s to present: 16,500 households: US$ 20.60 Gross, US$ 15.84–16.13 Actual to community Cullman-Hurt Community Wildlife Project, 1990s: US$ 14.50–120 Gross | ||

| Zimbabwe | Gross US$ 18.6-22.3 million, pre-2000 (land reform significantly reduced this income after 2000) | - | ≈US$ 1.56 million gross. 90% from hunting, 60% from elephant hunting 7-8.4% of Gross Turnover | CAMPFIRE, Average 1989–1999: ≈95,000 households: US$ 18.60 gross |

| Zambia | Gross US$ 12 million in 1999 | 21 hunting companies employing 400 people | US$ 700,000 gross, Gross 5.8% of Gross Turnover | ADMADE Program, 1991: 1,000 households Munyamadzi Corridor only, US$ 17 gross LIRDP, 1990s: 10,000 Households, US$ 22–37 Gross |

| ADMADE = Administrative Management Design for Game Management Areas & LIRDP = Luangwa Integrated Resource Development Project. Source: [40]. | ||||

| COSTS AND BENEFITS | US$ | % OF NET PROFITS (gross turnover) |

|---|---|---|

| GROSS TURNOVER | 818,402 | |

| Government Portion of Trophy Fee | 138,000 | |

| Gun Licenses | 6,000 | |

| Dipping Packing and Export Fees | 8,500 | |

| Client Hunting Licenses | 22,750 | |

| Hunting Block Fees (4 Blocks) | 20,000 | |

| Professional Hunters Licenses (5) | 10,000 | |

| Work Permits (5) | 2,500 | |

| Company License | 2,000 | |

| NET INCOME TO GOVERNMENT (UWA) | 209,750 | 39 (25.6% of gross turnover) |

| Remaining to Company | 608,652 | |

| RECURRING COSTS | ||

| PH DAILY RATE US$ 150/HUNTING DAY, 360 DAYS | 54,000 | |

| CAR RATE TO PH US$ 70/HUNTING DAY, 300 DAYS | 21,000 | |

| PH TRAVEL DAY US$ 40/TRAVEL DAY | 2,800 | |

| SALARY 2 NON HUNT PROF, US$ 100/DAY | 40,824 | |

| Salary CEO | 20,000 | |

| COMPANY RUNNING COSTS (ELEC, FUEL) | 100,000 | |

| MARKETING | 20,000 | |

| Dipping Packing Fees | 14,500 | |

| Subtotal | 273,124 | |

| Net To Company | 335,528 | |

| COMMUNITY BENEFITS | ||

| GENERAL STAFF | 15,000 | |

| OFF SEASON ANTI-POACHING (4 MOS) | 15,000 | |

| 20% Of Total Trophy Fee (Govt. + Company) | 47,942 | |

| NET INCOME TO COMMUNITY | 77,942 | 14 (9.5% of gross turnover, 5.9% if salaries discounted) |

| NET PROFIT TO COMPANY | 257,586 | 47 (gross profit margin 32%) |

| TOTAL NET PROFIT | 545,278 |

“...this industry is an ‘old boys club’ of white men who keep the clients and their networks to themselves for financial gain. The standards and requirements set for one to become a professional hunter, which you need before being registered as an outfitter, or before you can become the director of a hunting academy, are stacked against black individuals”[124]

3.3. CBNRM, Population Pressures & Land Use—Can Wildlife Compete?

- 56% overall decline in wildlife for most species in the last 20 years;

- White-bearded Wildebeest (Connochaetes taurinus albojubatus), 81% decline, 1977–1997, especially in the Loita plains—the main calving and breeding grounds that have been converted to wheat fields;

- Cape Buffalo (Syncerus caffer caffer) decline from 15,400 in the 1970s to 3,000 in 1994;

- Eland (Taurotragus oryx pattersonianus) from 5,700 in the 1980s to 1,025 in 1996;

- Kongoni/Bubal Hartebeest (Alcelaphus buselaphus cokii) from 4,150 to less than 1,400 over the last 20 years;

- Topi (Damaliscus korrigum) declined from 20,748 in 1988 to 8,900 in 1996;

- Warthog (Phacochoerus aethiopicus) decline by 88% from 1988–1996; and

- 72% decline in giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis), common waterbuck (Kobus ellipsiprymnus) and other antelope from 1988–1996.

3.4. CBNRM, Additional Shortcomings

3.5. Transfrontier Conservation Areas, CBNRM on Steroids Displacing Rural Communities

- The Great Limpopo Transfrontier Park (Gaza-Kruger-Gonarezhou Transfrontier Conservation Area (TFCA).

- The Four Corners (Near Victoria Falls where Zimbabwe, Namibia, Zambia and Botswana meet).

- ZIMOZA (Zimbabwe-Zambia-Mozambique Transboundary Area).

4. Innovative Attempts to overcome Shortcomings of CBNRM

4.1. “Project Noah”, Training Rural Africans, In Wildlife Management

- Sensitizing rural communities to the ecological and economic importance of their natural systems, and to develop the capacity within these communities to sustainably manage wildlife;

- Maintaining (develop) wildlife as a viable and alternative land use option in Africa outside parks and protected areas;

- Assisting in the development of grass roots democracies whereby rural communities can gradually take over ownership, management and the right to benefit from their wildlife and other natural resources;

- Eventually influencing wildlife utilization policy (bottom up approach);

- Creating a core of scientific expertise where students will become the future community wildlife managers, safari operators, government decision makers, or conservation NGO coordinators;

- Ensuring that the utilization (hunting) of wildlife in Africa remains (becomes) a viable option of income generation, thereby ensuring that future generations of sport hunters can continue to practice their sport.

- Establishing a network whereby graduated Noah students can have access to a decision support system (Housed at the Department of Nature Conservation at Tshwane University Of Technology) whereby technical and scientific support will be rendered to former students, their communities and decision makers;

- Eventually developing long-term ties with the various host countries and regional wildlife training institutions such as Mweka/Pasiansi and Garoua wildlife colleges, respectively in Tanzania and Cameroon.

| Botswana |

|

| Burkina Faso |

|

| Cameroon |

|

| Kenya |

|

| Namibia |

|

| Tanzania |

|

| Zambia |

|

| Zimbabwe |

|

4.2. Finding African Solutions to African Problems

Chasse Libre with Tikar Hunters, Cameroon

Chasse Libre with Dozo Hunters, Burkina Faso

| CAMNARES PILOT ONE HUNTER + CAMERMAN | BURKINA FASO CHASSE LIBRE PROGRAM, 2002 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| COST | Bongo hunt (Euro) | Percent gross turnover | 14 Day buffalo hunt (Euro) | Percent gross turnover |

| HUNTING LICENSE | 769 | 185 | ||

| TEMPORARY RIFLE IMPORT PERMIT | 451 | 185 | ||

| CERTIFICATE D'ORIGINE | 69 | 6 | ||

| VETERINARY CERTIFICATE | 46 | ? | ||

| BLOCK RENTAL (Government Daily Rate) | 923 | |||

| DAILY RATE (Community Fee) | 1,185 | 862 | ||

| TROPHY FEE BONGO | 1,539 | - | ||

| TROPHY FEE BUFFALO—ASSUME 1 BUF/PERSON/HUNT | - | 692 | ||

| TROPHY FEE ROAN | - | 462 | ||

| GOVERNMENT ECO-GUARDS | 923 | - | ||

| GOVERNMENT FEES CAMERAMAN | 1,539 | |||

| BENEFITS TO GOVERNMENT (without/with trophy fee) | 4,720/6,259 | 37/49 | 376 | 7 |

| COMMON PROPERTY BENEFIT (2 TROPHIES/HUNT) &/or COMMUNITY FEE | - | 2,016 | ||

| TOTAL EMPLOYMENT FOR COMMUNITY (8–14 people/hunt) | 867 | 549 | ||

| TOTAL COMMUNITY BENEFITS (without/with trophy fee) | 2,052/3,591 | 16/28 | 2565 | 47 |

| CAMNARES FEES | 2,462 | 19 | ||

| OTHER COSTS (vehicle, fuel, hotels, food, airfare ticket, tips, etc.) Lower figure occurs if airfare, hotels and trophy shipment excluded to make it is more comparable to Table 4 | 1,910-2,910 | 2,536-4,535 | ||

| TOTAL COST OF TRIP (Minus airfare, hotels and trophy shipment) | 12,683 | 5,477 | ||

4.3. Conservation and CBNRM on Their Own Fail

4.4. A Parting Shot

Fouta Djallon Mountains, Guinea Conakry

“You may think it wrong of me to hunt lion for a living. You get paid every two weeks down in the big city in your air-conditioned office. For one lion skin, I get what I make out of the ground in a year (poor lateritic soils). You can put me in jail but when I get out, I will do it again. I have a wife and children to feed. You have one of two choices if you wish me to stop. You can shoot me now or find me another way of life”[155]

Bwindi “Impenetrable Forest”, Uganda

“At Bwindi the activities of buffalo (now extinct) and elephant (now very few) caused disturbed secondary habitats which gorillas prefer. Secondary vegetation is now common in the forest due to timber harvesting. With better protection the forest is regenerating, and gorilla habitat is likely to decline. The level of plant use established at BINP (Bwindi National Park) is far below the impact needed to maintain secondary habitats at their present extent and causes less vegetation destruction than tourist trails cut daily for gorilla viewing”.

“Your schools, clinics and roads are well and good, but they don't fill empty bellies or pay school fees. We want access to the forest”.[69]

“Under pressure from traditional Western conservationists, who had come to believe that wilderness and human community were incompatible, the Batwa (Pygmies) were forcibly expelled from their homeland”.[62]

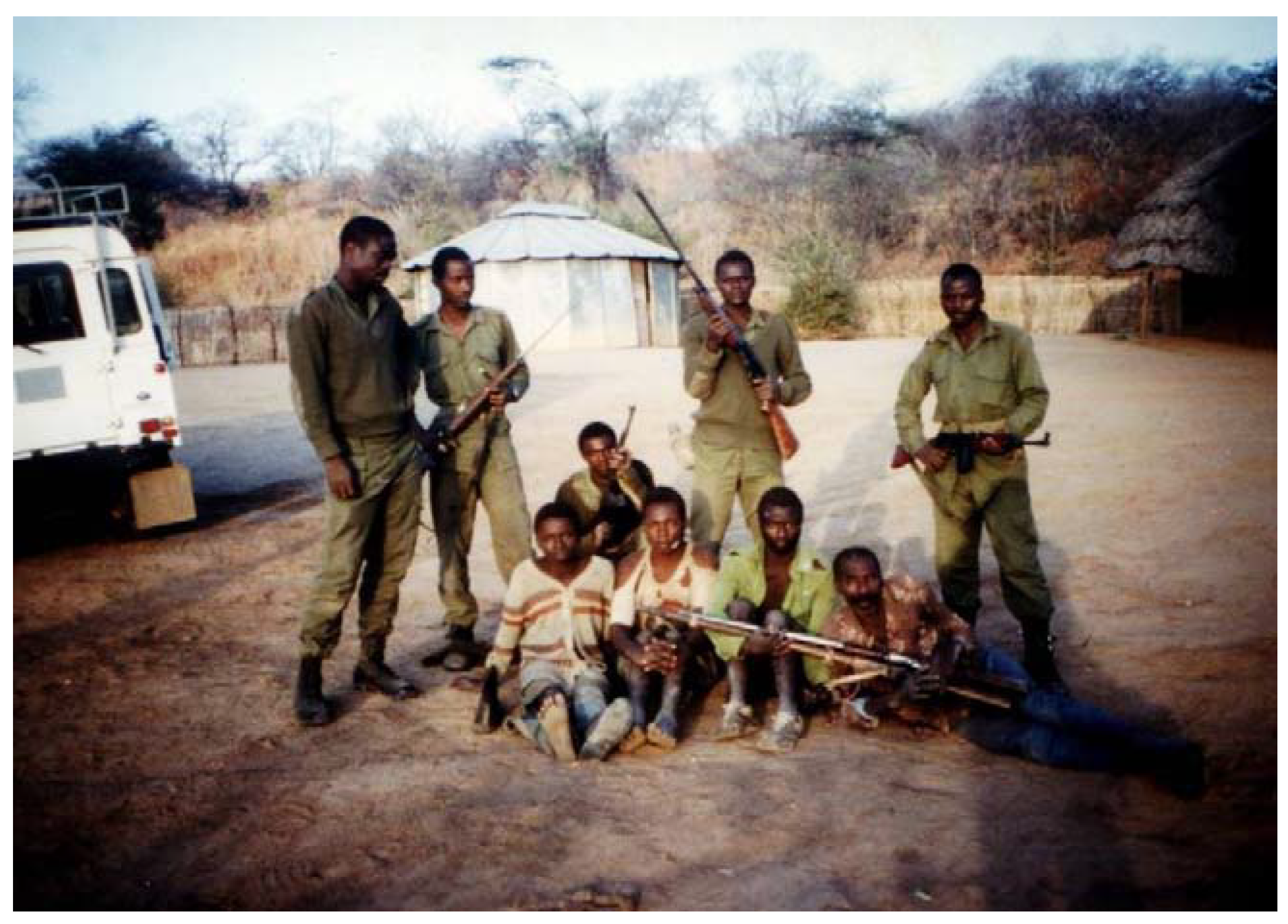

Munyamadzi Corridor, Zambia

- The 17 year-old said he didn't know what he was getting into and that he only went along because he had been told to do so;

- The 19 year-old had been poaching with the old man since 1987; and

- The 23 year-old had been poaching with the old man since 1991.

5. Conclusions

References

- Diamond, J. Collapse. How societies choose to fail or succeed; Viking Penguin: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Brantingham, J.P. Hominid-Carnivore coevolution and invasion of the predatory guild. J. Anthropol. Sci. 1998, 17, 327–353. [Google Scholar]

- Burkhardt, J.W. Herbivory in the intermountain West. An overview of evolutionary history, historic cultural impacts and lessons from the past; Station Bulletin 58 of the Idaho Forest, Wildlife and Range Experiment Station College of Natural Resources: University of Idaho, Moscow, ID, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Denevan, W.M. The pristine myth: The landscape of the Americas in 1492. Annals Assoc. Am. Geogr. 1992, 82, 367–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grayson, D.K. Late Pleistocene mammalian extinction in North America: Taxonomy, chronology, and explanations. J. World Prehistor. 1991, 5, 193–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leakey, R.; Lewin, R. The sixth extinction. Biodiversity and its survival; Orion Books: London, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, P.S. Refuting late Pleistocene extinction models. In Dynamics of Extinction; Elliot, D.K., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, P.S. 40,000 years of extinctions on the ‘planet of doom’. Paleogeography, Paleoclimatology, Paleoecology 1990, 82, 187–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steadman, D.P. Prehistoric extinctions of Pacific island birds: Biodiversity meets zooarchaeology. Science 1995, 267, 1123–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Child, G. Growth of modern nature conservation in Southern Africa. In Parks in transition. biodiversity, rural development and the bottom line; Child, B., Ed.; Southern African Sustainable Use Group (SASUSG)/IUCN. Earthscan: London, UK; Sterling, Virginia, USA, 2004; pp. 7–17. [Google Scholar]

- Cullis, A.; Watson, C. Winners and losers: privatizing the commons in Botswana; Securing the Commons No. 9. SMI (Distribution Services) Ltd.: Stevenage, Hertfordshire, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Dadnadji, K.K.; van Wetten, J.C.J. Traditional management systems and integration of small scale interventions in the Logone floodplains of Chad. Towards the wise use of Wetlands; Davis, T.J., Ed.; The RAMSAR Library: Gland, Switzerland, 1993. Available online: http://www.ramsar.org/lib/lib_wise.htm#cs7 (Accessed 7 July 2009).

- Hinz, M.O. Without chiefs there would be no game. Customary law and nature conservation; Out of Africa Publishers: Windhoek, Namibia, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Mariko, K.A. Le monde mysterieux des chasseurs traditionnels. Agence de Cooperation Culturelle et Technique; Les Nouvelles Editions Africaines: Paris, France; Dakar, Senegal; Abidjan, Ivory Coast; Lomé, Togo, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Marks, S.A. The imperial lion. Human dimensions of wildlife management in Central Africa; Westview Press: Boulder, Colorado, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Njiforti, H.L.; Tchamba, N.M. Conflict in Cameroon. Parks for or against people? In The law of the mother. Protecting indigenous peoples in protected areas; Kemf, E., Ed.; Sierra Club Books: San Francisco, USA, 1993; pp. 173–178. [Google Scholar]

- Claridge, G.C. Wild bush tribes of tropical Africa. An account of adventure and travel amongst pagan people of tropical Africa, with a description of their manners of life, customs, heathenish rites and ceremonies, secret societies, sport and warfare collected during a sojourn of twelve years; Seeley, Service: London, UK, 1922. [Google Scholar]

- Hagberg, S. The authority and violence of a hunters’ association in Burkina Faso. Each bird is sitting in its own tree. In Conflicts over land and water in Africa; Derman, B., Odgaard, R., Sjaastad, E., Eds.; James Curry: Oxford, UK; Michigan State University Press: East Lansing, USA; University of KwaZulu-Natal Press: Pietermaritzburg, South Africa, 2007; pp. 187–201. [Google Scholar]

- Ibo, G.J. Perceptions et pratiques environnmentales en milieu traditionnel Africaines: L’exemple des societes Ivoiriennes anciennes; ORSTOM, Centre de Petit Bassam: Abidjan, Ivory Coast, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, I.; Amin, M. Ivory crisis; Chatto and Windus: London, UK; Camerapix Publishers International: Nairobi, Kenya, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Traore, D. Restitution des resultants de l’enquete dur la gestion traditionnelle de la chasse. Cas specifique des Dozo; Ministere de L’Environnment de L’Eau, Secretariat General. Direction Generale des Eaux et Forets, Direction Regionale de L’Environnment et des Eaux et Forets des Hauts-Bassins. Direction Provinciale de L’Environnement et des Eaux et Forêts de la Comoé. Service Provincial Faune: Chasse, Burkina Faso, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- McGregor, J. Living with the river. Landscape and memory in the Zambezi Valley, northwest Zimbabwe. In Social history and African environments; Beinart, W., McGregor, J., Eds.; James Currey: Oxford, UK; Ohio University Press: Athens, OH, USA; David Phillip: Cape Town, South Africa, 2003; pp. 87–105. [Google Scholar]

- Solly, H. “Vous etes grands, nous sommes petits”. The implications of Bulu history, culture and economy for an integrated conservation and development project (ICDP) in the Dja Reserve, Cameroon; Original thesis presented in view of obtaining a Doctorate in the Social Sciences. Free University Of Brussels. Faculty of Social sciences, politics and economics Centre for social and cultural anthropology: Brussels, Belgium, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Wannenburgh, A.; Johnson, P.; Bannister, A. The Bushmen; Struik: Capetown, South Africa, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Hitchcock, R.K. Hunting is our heritage: The struggle for hunting and gathering rights among the San of Southern Africa. In Parks, property and power; Anderson, D.G., Kazunobu, I., Eds.; Senri Ethnological Studies 59; National Museum of Ethnology: Osaka, Japan, 2001; pp. 139–156. [Google Scholar]

- Ritter, E.A. Shaka Zulu. The biography of the founder of the Zulu nation; Penguin Books: New York, NY, USA, 1955. [Google Scholar]

- Boone, C. Political topographies of the African state. Territorial authority and institutional choice; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hakimzumwami, E. Community wildlife management in Central Africa: A regional review; Evaluating Eden Series, Discussion Paper No 10. International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED): London, UK, 2000. Available online: http://www.iied.org/pubs/pdfs/7804IIED.pdf (Accessed 8 July 2009).

- Hitchcock, R.K. We are the First People: Land, natural resources and identity in the Central Kalahari, Botswana. J. South. Afr. Stud. 2002, 28, 797–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitchcock, R.K. Sharing the land: Kalahari San property rights and resource management. In Property and equality. Ecapsulation, commercialization, discrimination; Widlok, T., Tadesse, W.G., Eds.; Berghahn Books: London, UK, 2005; Vol. II, pp. 191–207. [Google Scholar]

- Hitchcock, R.K. Land, livestock, and leadership among the Ju/’hoansi San of North Western Botswana. Anthropologica 2003, 45, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, L. The Kung of Nyae Nyae; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Moorehead, R. Changes taking place in common property resource management in the inland Niger delta of Mali. In Common property resources: ecology and community based sustainable development; Berkes, F., Ed.; Belhaven Press: London, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, J. Influence des acteurs externs sur leas Baka sans la region Lobeké. Etude de Cas; MINEF Cameroon and GTZ PROFORNAT (Projet de Gestion des Forets Naturelles): Yokodouma, Cameroon, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, A.B. Pastoralism in Africa. Origins and development ecology; C. Hurst: London, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Hitchcock, R.K. Traditional African wildlife utilization: Subsistence hunting, poaching and sustainable use. In Wildlife conservation and sustainable use; Prins, H.H.T., Grootenhuis, J.G., Dolan, T., Eds.; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Boston, MA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Turnbull, C. The mountain people. The classic account of a society too poor for morality; Triad/Paladin Grafton Books: London, UK, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Dublin, H.T. Dynamics of the Serengeti-Mara woodlands. An historical perspective. Forest and Conservation History 1991, 35, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjekshus, H. Ecological control and economic development in East African history. The case of Tanganyika, 1850-1950; Heinemann Educational Books: London, UK, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- DeGeorges, P.A.; Reilly, B.K. A critical evaluation of conservation and development in Sub-Saharan Africa; The Edwin Mellen Press: Lewiston, New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Carruthers, J. The Kruger National Park. A social and political history; University of Natal Press: Pietermaritzburg, South Africa, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Maddox, G. ‘Degradation narrative’ and ‘population time bombs’: Myths and realities about African environments. In South Africa’s environmental history. Cases and comparisons; Dovers, S., Edgecombe, R., Guest, B., Eds.; David Philip Publishers: Capetown, South Africa, 2002; pp. 250–258. [Google Scholar]

- MacKenzie, J.M. The empire of nature. Hunting, conservation and British imperialism. Studies in imperialism; Manchester University Press: Manchester, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Dorst, J. Before nature dies; Collins & Sons: London, UK; Houghton Mifflin Co: Boston, MA, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Pringle, J.A. The conservationists and killers. The story of game protection and the Wildlife Society of Southern Africa; T.V. Bulpin and Books of Africa: Cape Town, South Africa, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Cattrick, A. Spoor of blood; Standard Press Limited: Cape Town, South Africa, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Wels, H. Fighting over fences. Organization co-operation and reciprocal exchange between the Save Valley Conservancy and its neighbouring communities in Zimbabwe; Vrije University: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Giles-Vernick, T. Cutting the vines of the past. Environmental histories of the Central African rain forest; The University Press of Virginia: Charlottesville, VA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Baldus, R.D. Wildlife conservation in Tanganyika under German colonial rule; Tanzanian-German Development Cooperation: Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, 2001. Available online: http://www.wildlife-programme.gtz.de/wildlife/download/colonial.pdf (Accessed 9 July 2009).

- Funaioli, V.; Simonetta, A.M. Statut actuel des Ongules en Somalie. Mammalia 1961, 25, 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Before nature dies; Dorst, J. (Ed.) Collins & Sons: London & Glasgow, UK, 1970.

- Adams, W. Nature and the colonial mind. In Decolonizing nature. Strategies for conservation in a post-colonial era; Adams, W., Mulligan, M., Eds.; Earthscan Publications: London, UK, 2003; pp. 16–50. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, D.; Grove, R. Conservation in Africa: People, policies and practice; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Bond, I.; Child, B.; de la Harpe, D.; Jones, B.; Barnes, J.; Anderson, H. Private land contribution to conservation in South Africa. In Parks in transition. Biodiversity, rural development and the bottom line; Child, B., Ed.; Earthscan Publications: London, UK, 2004; pp. 29–61. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, C.C. Politicians and poachers. The political economy of wildlife policy in Africa; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Neumann, R.P. Imposing wilderness: Struggles over livelihood and nature preservation in Africa; University of California Press: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Murombedzi, J. Pre-colonial and colonial conservation practices in southern Africa and their legacy today; IUCN: Harare, Zimbabawe, 2003. Available online: http://dss.ucsd.edu/~ccgibson/docs/Murombedzi%20%20Precolonial%20and%20Colonial%20Origins.pdf (Accessed 3 July 2009).

- Prins, H.H.T.; Grootenhuis, J.G.; Dolan, T.T. (Eds.) Wildlife conservation by sustainable use; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2000.

- Bonner, R. At the hand of man. Peril and hope for Africa’s wildlife; Alfred, A., Ed.; Knopf: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Vanderpost, C. Protected areas in Ngamiland, Botswana: Investigating options for conservation-development through human footprint mapping. Int. J. Environ. Stud. 2007, 64, 555–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colchester, M. Salvaging nature: Indigenous peoples, protected areas and biodiversity conservation; Forest Peoples Program: Moreton-in-Marsh, UK, 2003, 2nd ed. World Rainforest Movement, International Secretariat: Maldonado 1858, Montevideo. Available online: http://www.wrm.org.uy/subjects/PA/texten.pdf (Accessed 8 July 2009).

- Chape, S.; Blyth, S.; Fish, L.; Fox, P.; Spalding, M. United Nations list of protected areas; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland and Cambridge, UK; UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre, Cambridge, UK, 2003. Available online: http://www.unepwcmc.org/wdpa/unlist/2003_UN_LIST.pdf (Accessed 9 July 2009).

- Dowie, M. Conservation refugees. Available online: http://www.orionmagazine.org/index.php/articles/article/161/ (Accessed 10 July 2009).

- Geisler, C.; de Sousa, R. From refugee to refugee: The African case. Working Paper 38; Land Tenure Centre, University of Wisconsin: Madison, WI, USA, 2000. Available online: http://ageconsearch.umn.edu/bitstream/12777/1/ltcwp38.pdf (Accessed 7 July 2009).

- World database on protected areas as of January 31 2008; UNEP/WCMC: Cambridge, UK, 2009. Available online: http://www.wdpa.org/ (Accessed 15 March 2009).

- Brockington, D.; Igoe, J. Anthropology conservation protected areas and identity politics; QEG conference paper. Oxford Department of International Development: Oxford, UK, 2005. Available online: http://www.colby.edu/environ/courses/ES118/Readings/Brockington%20et%20al%202006.pdf (Accessed 1 August 2009).

- Brockington, D.; Igoe, J. Eviction for conservation. A global overview. Conservation and Society. 2006, 4, pp. 424–470. Available online: http://www.conservationrefugees.org/pdfdoc/EvictionforConservation.pdf (Accessed 1 August 2009).

- Brockington, D.; Igoe, J.; Schmidt-Soltau, K. Conservation, human rights, and poverty reduction. Conservation Biology. 2006, 20, pp. 250–252. Available online: http://www.colby.edu/environ/courses/ES118/Readings/Brockington%20et%20al%202006.pdf (Accessed 1 August 2009). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Igoe, J.; Croucher, B. Poverty reduction meets the spectacle of nature: does reality matter? Transnational influence in large landscape conservation in Northern Tanzania, Draft, 2006. Igoe, Assistant Professor, Department of Anthropology, University of Colorado at Denver, james.igoe@cudenver.edu; Croucher, student, Department of Anthropology, University of Colorado at Denver, becroucher@comcast.net.

- Ogwang, D.A.; DeGeorges, A. Community participation in interactive park planning and the privatization process in Uganda’s national parks; Prepared for Uganda National Parks (UNP): Kapala, Uganda; The U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID): Nairobi, Kenya, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Hulme, D. Community conservation in practice: A case study of Lake Mburo National Park; Working Paper No. 3. Community Conservation Research in Africa. Principles and Comparative Practice. Institute for Development Policy and Management, University of Manchester: Manchester, UK, 1997. Available online: http://www.sed.manchester.ac.uk/idpm/research/publications/archive/cc/cc_wp03.pdf (Accessed August 2009).

- Magome, H.; Grossman, D.; Fakir, S.; Stowell, Y. Partnerships in conservation: The state, private sector and the community at Madikwe Game Reserve, North-West Province, South Africa; Evaluating Eden Series, Discussion Paper No 7. International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED): London, UK, 2000. Available online: http://www.iied.org/pubs/pdfs/7802IIED.pdf (Accessed August 2009).

- Hitchcock, R.K.; Biesle, M.; Lee, R. The San of Southern Africa: A status report; American Anthropological Association: Arlington, VA, USA, 2003. Available online: http://www.aaanet.org/committees/cfhr/san.htm (Accessed 1 August 2009).

- Survival International. The Bushmen; Survival International: London, UK, 2009. Available online: http://www.survival-international.org/tribes/bushmen/ (Accessed 1 August 2009).

- Duffy, R. Killing for conservation. Wildlife policy in Zimbabwe; African Issues; The International African Institute in association with James Currey: Oxford, UK; Indiana University Press: Bloomington & Indianapolis, USA; Weaver: Harare, Zimbabwe, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Child, G. Wildlife and people. The Zimbabwean success. How conflict between animals and people became progress for both; Wisdom Foundation: Harare, Zimbabwe; New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Hasler, R. An overview of the social, ecological and economic achievements and challenges of Zimbabwe’s CAMPFIRE Project; Evaluating Eden Series, Discussion Paper No 3. International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED): London, UK, 1999. Available online: http://www.iied.org/pubs/pdfs/7796IIED.pdf (Accessed July 2009).

- Bond, I. CAMPFIRE and the incentives for institutional change. In African wildlife and livelihoods: The promise and performance of community conservation; Hulme, D., Murphree, M., Eds.; James Curry: Oxford, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Sibanda, B. Community wildlife management in Zimbabwe: The case of CAMPFIRE in the Zambezi Valley. In Rights, resource and rural development. Community-based natural resource management in Southern Africa; Fabricius, C., Kock, E., Magome, H., Turner, S., Eds.; Earthscan: London, UK, 2004; pp. 248–258. [Google Scholar]

- Murphree, M.W. Congruent objectives, competing interests and strategic compromise: Concepts and processes in the evolution of Zimbabwe's CAMPFIRE program; Working Paper No. 2. Community Conservation Research in Africa. Principles and Comparative Practice; Institute for Development Policy and Management, University of Manchester: Manchester, UK, 1997. Available online: http://www.sed.manchester.ac.uk/idpm/research/publications/archive/cc/cc_wp02.pdf (Accessed 8 July 2009).

- Living with wildlife. How CAMPFIRE communities conserve their natural resources; African Resources Trust: Harare, Zimbabwe, 2002.

- Metcalfe, S. Whose resources are at stake? Community-based conservation and community self-governance. The Rural Extension Bulletin 1996, 10, 14–18. [Google Scholar]

- Murombedzi, J.C. The dynamics of conflict in environmental management policy making in the context of the communal lands management program for indigenous resources (CAMPFIRE). Ph.D. Thesis, Centre for Applied Social Sciences, University of Zimbabwe, Harare, Zimbabwe, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Murombedzi, J.C. Devolution and stewardship in Zimbabwe’s CAMPFIRE program. J. Int. Devel. 1999, 11, 287–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ADMADE Foundation. Communities managing wildlife to raise rural standards of living and conserve biodiversity; Wildlife Conservation Society: New York, NY, USA; National Parks; Wildlife Service: Lusaka, Zambia, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- DeGeorges, A. An evaluation. Today and the future. Policy issues and direction; USAID/Zambia and NPWS/Zambia: Lusaka, Zambia, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Lyons, A. An effective monitoring framework for Community-Based Natural Resource Management: A case study of the ADMADE program in Zambia. M.Sc. Thesis; University of Florida: Gainesville, USA, 2000. Available online: www.cbnrm.net/pdf/lyons_a_001_admadethesis.pdf (Accessed 9 July 2009).

- Lewis, D.M.; Alpert, P. Trophy hunting and wildlife conservation in Zambia. Conserv. Biol. 1997, 11, 50–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, I.P.A. A review of conservation and safari hunting on Zambia’s customary land. 2006, (in press). [Google Scholar]

- Marks, S.A. Large mammals and a brave people. Subsistence hunters in Zambia; University of Washington Press: Seattle, WA, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Marks, S.A. Local hunters and wildlife surveys: a design to enhance participation. Afr. J. Ecol. 1994, 32, 233–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marks, S.A. Local hunters and wildlife surveys: An assessment and comparison of counts for 1989, 1990 and 1993. Afr. J. Ecol. 1996, 34, 237–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marks, S.A. Back to the future: Some unintended consequences of Zambia’s community-based wildlife program (ADMADE). Afr. Today 2001, 48, 121–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marks, S.A. The legacy of a Zambian community-based wildlife program. A cautionary tale. Natural resources as community assets. Lessons from two continents. Lyman, M.W., Child, B., Eds.; 2005, pp. 183–209. Available online: http://www.sandcounty.net/assets/chapters/forward_introduction.pdf (Accessed 7 July 2009).

- Marks, S.A.; Fuller, R.J. Enclosure of an important wildlife commons in Zambia; University of Gloucestershire: Cheltenham, UK, 2008. Available online: http://dlc.dlib.indiana.edu/archive/00003874/00/Marks_149401.pdf (Accessed 7 July 2009).

- Boggs, L.P. Community power, participation, conflict and development choice: Community wildlife conservation in the Okavango region of Northern Botswana; Evaluating Eden Series, Discussion Paper No 17. International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED): London, UK, 2000. Available online: http://www.iied.org/pubs/pdfs/7815IIED.pdf (Accessed 8 July 2009).

- Boggs, L. Community-based natural resource management in the Okavango Delta. In Rights, resource and rural development. Community-based natural resource management in Southern Africa; Fabricius, C., Kock, E., Magome, H., Turner, S., Eds.; Earthscan: London, UK, 2004; pp. 147–159. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, B. Community-based natural resource management in Botswana and Namibia: An inventory and preliminary analysis of progress; International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED): London, UK, September Evaluating Eden Series, Discussion Paper No 6. 1999. Available online: http://www.iied.org/pubs/pdfs/7799IIED.pdf (Accessed 7 July 2009).

- Berger, D.J. The making of a conservancy. The evolution of Nyae Nyae Conservancy. Restoring human dignity with wildlife wealth, 1997-2002; WWF/LIFE Program; USAID: Windhoek, Namibia, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, B. Rights, revenue and resources: The problems and potential of conservancies as community wildlife management institutions in Namibia; Evaluating Eden Series, Discussion Paper No 2. International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED): London, UK, 1999. Available online: http://www.iied.org/pubs/pdfs/7795IIED.pdf (Accessed 9 July 2009).

- Livelihoods and CBNRM in Namibia: The findings of the WILD Project. Final Technical Report of the Wildlife Integration for Livelihood Diversification Project (WILD); Long, S.A. (Ed.) Directorates of Environmental Affairs and Parks and Wildlife Management, Ministry of Environment and Tourism, the Government of the Republic of Namibia: Windhoek, Namibia, 2004. Available online: http://www.met.gov.na/programmes/wild/finalreport/TOC/TOC(p1-4).pdf (Accessed 7 July 2009).

- USAID Support to the community-based natural resource management program in Namibia: LIFE program review; United States Agency for International Development (USAID), Biodiversity Assessment and Technical Support (BATS) Program: Washington, DC, USA, 2008. Available online: http://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PDACL549.pdf (Accessed 8 July 2009).

- Weaver, L.C.; Skyer, P. Conservancies: integrating wildlife land-use options into the livelihood, development, and conservation strategies of Namibian communities. A Paper Presented at the 5th World Parks Congress to the: Animal Health and Development (AHEAD) Forum: Durban, South Africa, A Paper Presented at the 5th World Parks Congress to the: Animal Health and Development (AHEAD) Forum: Durban, South Africa, 2003. Available online http://www.usaid.gov/na/pdfdocs/WPCAHEAD_2.pdf (Accessed 8 July 2009). [Google Scholar]

- Weaver, L.C.; Skyer, P. Conservancies: Integrating wildlife land-use options into the livelihood, development and conservation strategies of Namibian communities. Conservation and development interventions at the wildlife/livestock interface. Implications for wildlife, livestock and human health; Osofsky, S.A., Ed.; Occasional Paper of the IUCN Species Survival Commission No. 30. IUCN: Gland, Switzerland; Cambridge, UK, 2005; pp. 89–104. Available online http://iucn.org/dbtw-wpd/edocs/SSC-OP-030lr.pdf (Accessed 7 July 2009).

- Wiessner, P. Population, subsistence, and social relations in the Nyae Nyae Area: Three decades of change; Report on file at the Nyae Nyae Development Foundation of Namibia: Windhoek, Namibia, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Ashley, C.; Mdoe, N.; Reynolds, L. Rethinking wildlife for livelihoods and diversification in rural Tanzania: A case study from Northern Selous; LADDER Working Paper No.15. DFID: London, UK, 2002. Available online http://www.odi.org.uk/resources/download/2927.pdf (Accessed 6 July 2009).

- Baldus, R.D.; Hahn, R.; Kaggi, D.; Kaihula, S.; Murphree, M.; Mahundi, C.C.; Roettcher, K.; Siege, L.; Zacharia, M. Experiences with community based wildlife conservation in Tanzania. Tanzania Wildlife; Discussion Paper No 29. Wildlife Division/GTZ: Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, 2001. Available online http://www.wildlife-programme.gtz.de/wildlife/download/nr_29_1.pdf (Accessed 7 July 2009).

- Baldus, R.D.; Kaggi, D.T.; Ngoti, P.M. Community based conservation (CBC): Where are we now? Where are we going? 15 years of CBC. The Newsletter of the Wildlife Conservation Society of Tanzania, Miombo. 2004. Available online: http://www.wildlife-programme.gtz.de/wildlife/download/cbc.pdf (Accessed 9 July 2009).

- Barrow, E.; Gichohi, H.; Infield, M. Rhetoric or reality? A review of community conservation and practice in East Africa; Evaluating Eden Series No 5. International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED): London, UK, 2000. Available online: http://www.iied.org/pubs/pdfs/7807IIED.pdf (Accessed 7 July 2009).

- Clarke, J.E. An evaluation of the Cullman and Hurt Community Wildlife Project, Tanzania. Conservation Force 2001.

- Gillingham, S. Giving wildlife value: A case study of community wildlife management around the Selous Game Reserve, Tanzania; Department Biological Anthropology, University of Cambridge: Cambridge, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Junge, H. Decentralisation and community-based natural resource management in Tanzania. The case of local governance and community-based conservation in districts around the Selous Game Reserve; Tanzania Wildlife Discussion Paper No. 32, Wildlife Division Deutsche Gesellschaft für Technische Zusammenarbeit GTZ Wildlife Program. Dar Es Salaam, Tanzania, 2002. Available online: http://www.wildlife-baldus.com/download/nr_32.pdf (Accessed 9 July 2009).

- Kibonde, B.O. Wildlife poaching in Tanzania: Case study of the Selous Game Reserve; Tshwane University of Technology: Pretoria, South Africa, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Child, B. The Luangwa Integrated Development Project, Zambia. In Rights, resource and rural development. Community-based natural resource management in Southern Africa; Fabricius, C., Kock, E., Magome, H., Turner, S., Eds.; Earthscan: London, UK, 2004; pp. 235–247. [Google Scholar]

- Child, B.; Clayton, B.D. Transforming approaches to CBRNM: Learning from the Luangwa experience; Southern Africa Sustainable Use Specialist Group, IUCN–The World Conservation Union Regional Office for Southern Africa: Harare, Zimbabwe, 2002. Available online: http://www.sasusg.net/web/files/papers/CBNRM%20in%20Lupande%20GMA%20%20Brian%20Child%20and%20Dalal%20Clayton%20.pdf (Accessed 9 July 2009).

- Murphree, M.W. Community based conservation: Old ways, new myths and enduring challenges. Experiences with community based wildlife conservation in Tanzania; Baldus, R.D., Hahn, R., Kaggi, D., Kaihula, S., Murphree, M., Mahundi, C.C., Roettcher, K., Siege, L., Zacharia, M., Eds.; Tanzania Wildlife Discussion Paper No 29. Wildlife Division/GTZ: Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, 2001. Available online: http://www.wildlife-programme.gtz.de/wildlife/download/nr_29_1.pdf (Accessed July 2009).

- Barrow, E.; Murphree, M. Community conservation from concept to practice: A practical framework; Working Paper No. 8. Institute for Development Policy and Management, University of Manchester: Manchester, UK, 1998. Available online: http://www.sed.manchester.ac.uk/idpm/research/publications/archive/cc/cc_wp08.pdf (Accessed 7 July 2009).

- Jones, T.B.B.; Murphree, M.W. Community-based natural resources management as a conservation mechanism: Lessons and directions. In Parks in transition. Biodiversity, rural development and the bottom line; Child, B., Ed.; Earthscan Publications: London, UK, 2004; pp. 63–103. [Google Scholar]

- Murombedzi, J. Devolving the expropriation of nature. The ‘devolution’ of wildlife management in southern Africa. In Decolonizing nature. Strategies for conservation in a post-colonial era; Adams, W., Mulligan, M., Eds.; Earthscan Publications: London, UK, 2003; pp. 135–151. [Google Scholar]

- Rights, resource and rural development. Community-based natural resource management in Southern Africa; Fabricius, C.; Kock, E.; Magome, H.; Turner, S. (Eds.) Earthscan: London, UK; Sterling, Virginia, 2004.

- IUCN/SASUSG. Community wildlife management in Southern Africa a regional review; November. IUCN–The World Conservation Union Regional Office For Southern Africa, Southern Africa Sustainable Use Specialist Group (SASUSG). Evaluating Eden Series, Working Paper No. 11. International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED): London, UK, 1997. Available online: http://www.iied.org/pubs/pdfs/7805IIED.pdf (Accessed 9 July 2009).

- Hurt, R.; Ravn, P. Hunting and benefits: An overview of hunting in Africa with special reference to Tanzania. In Wildlife conservation by sustainable use; Prins, H.H.T., Grootenhuis, J.G., Dolan, T.T., Eds.; Lower Academic Publishers: Boston, Mass, USA, 2000; pp. 295–314. [Google Scholar]

- de la Harpe, D.; Fernhead, P.; Hughes, G.; Davies, R.; Spenceley, A.; Barnes, J.; Cooper, J.; Child, B. Does commercialization of protected areas threaten their conservation goals? In Parks in transition. Biodiversity, rural development and the bottom line; Child, B., Ed.; Earthscan Publications: London, UK, 2004; pp. 189–216. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, H. Sustainable utilization and African wildlife policy: The case of Zimbabwe’s Communal Areas’ Management Program for Indigenous Resources (CAMPFIRE): Rhetoric of reality. An overview of the social, ecological and economic achievements and challenges of Zimbabwe’s CAMPFIRE Project. Hasler, R., Ed.; Evaluating Eden Series, Discussion Paper No 3. Available online: http://www.iied.org/pubs/pdfs/7796IIED.pdf (Accessed 7 July 2009).

- RSA Community Organizations. Statement on hunting; Submitted to the Panel of Experts on Professional and Recreational Hunting, Ministry of Environment and Tourism: Pretoria, South Africa, 2005. Available online: http://www.deat.gov.za/HotIssues/2005/29062005/Community_statement_on_Hunting.doc (Accessed July 2009).

- Junge, H. Democratic decentralization of natural resources in Tanzania. The case of local governance and community-based conservation in districts around the Selous Game Reserve; GTZ. Tropical Ecology Support Program (TOEB): Eschborn, Germany, 2004. [Google Scholar]

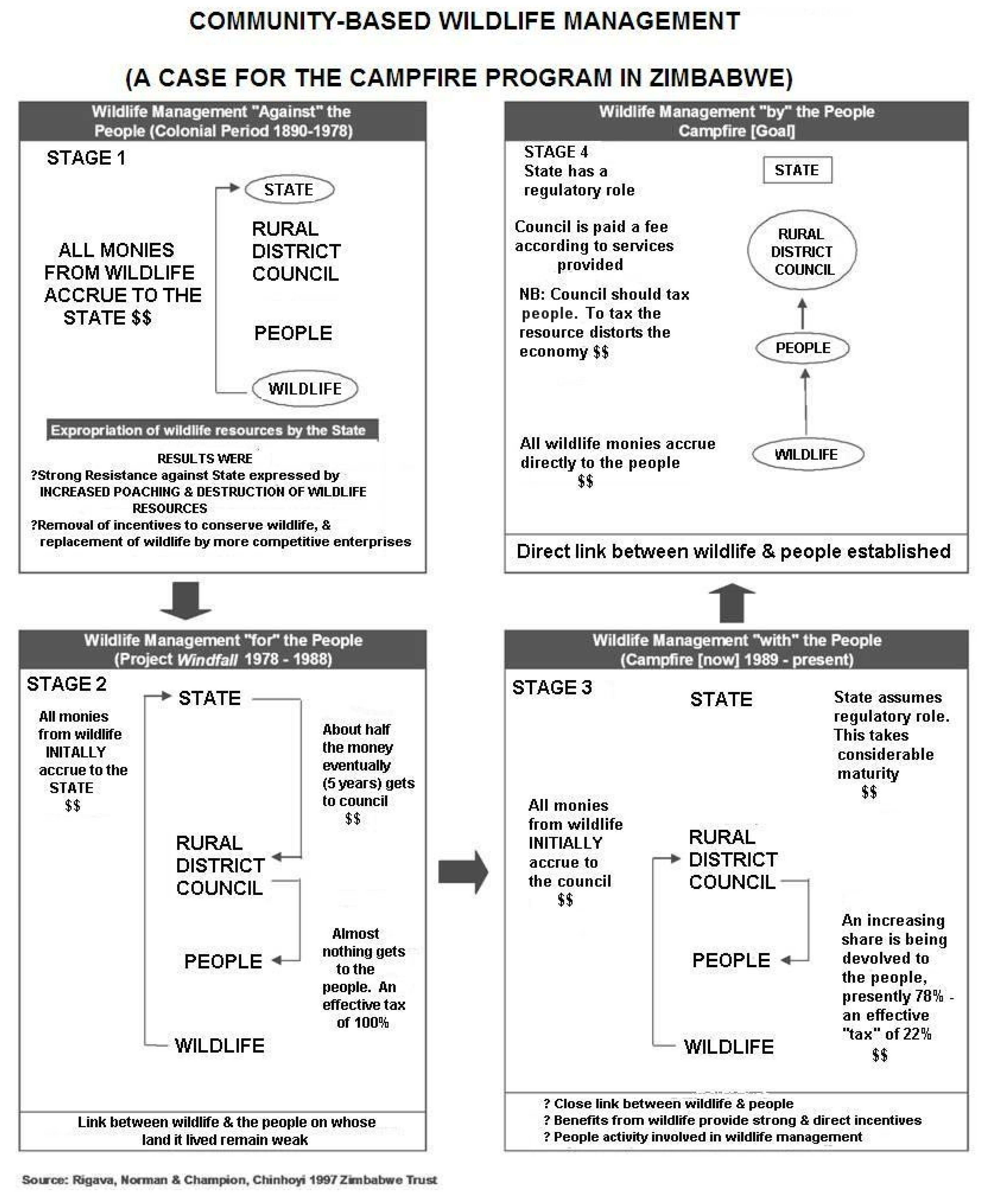

- Rigava, N.; Chinhoyi, C. Community-based natural resource management. A case for the CAMPFIRE program in Zimbabwe. A Figure/Poster. Provided by Norman Rigava then with WWF/Zimbabwe. 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Murphree, M.W. Synergizing conservation incentives: from local-global conflict to compatibility; Working Paper No. 7. Community Conservation Research in Africa. Principles and Comparative Practice. Institute for Development Policy and Management, University of Manchester: Manchester, UK, 1998. Available online: http://www.sed.manchester.ac.uk/idpm/research/publications/archive/cc/cc_wp07.pdf (Accessed 8 July 2009).

- Emerton, L. The nature of benefits and the benefits of nature: Why wildlife conservation has not economically benefited communities in Africa; Working Paper No. 5. Community Conservation Research in Africa. Principles and Comparative Practice. Institute for Development Policy and Management, University of Manchester: Manchester, UK, 1998. Available online: http://www.sed.manchester.ac.uk/idpm/research/publications/archive/cc/cc_wp05.pdf (Accessed 9 July 2009).

- Waithaka, J. Maasai Mara—an ecosystem under siege: an African case study on the social dimension of rangeland conservation. Afr. J. Range For. Sci. 2004, 21, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katerere, Y.; Chikoku, H. Can devolution deliver benefits of community-based natural resource management (CBNRM) initiatives? IUCN Regional Office Southern Africa (ROSA): Harare, Zimbabwe. In WSP. The long walk to sustainability. A Southern African perspective; World Summit Publication, HIS: Johannesburg, South Africa, 2002; pp. 53–55. [Google Scholar]

- Baldus, R.D.; Cauldwell, A.E. Tourist hunting and its role in development of Wildlife Management Areas in Tanzania; GTZ: Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, 2004. Available online: http://www.cic-wildlife.org/uploads/media/Hunting_Tourism.pdf (Accessed 1 August 2009).

- Watkin, J.R. The evolution of ecotourism in East Africa: From an idea to an industry. Summary of the Proceedings of the East African Regional Conference on Ecotourism; International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED): London, UK, 2003. Available online: http://www.iied.org/pubs/pdfs/9223IIED.pdf (Accessed 1 August 2009).

- Roe, D.; Mayers, J.; Grieg-Gran, M.; Kothari, A.; Fabricius, C.; Hughes, R. Evaluating Eden: Exploring the myths and realities of community-based wildlife management; International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED): London, UK, September Evaluating Eden, Series No 8. 2000. Available online: http://www.iied.org/pubs/pdfs/7810IIED.pdf (Accessed 9 July 2009).

- Fairhead, J.; Leach, M. Science, society and power. Environmental knowledge and policy in West Africa and the Caribbean; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Roe, D.; Jack, M. Case studies of community-based wildlife Management; Evaluating Eden Series No 9. International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED): London, 2001. Available online: http://www.iied.org/pubs/pdfs/9012IIED.pdf (Accessed 6 August 2009).

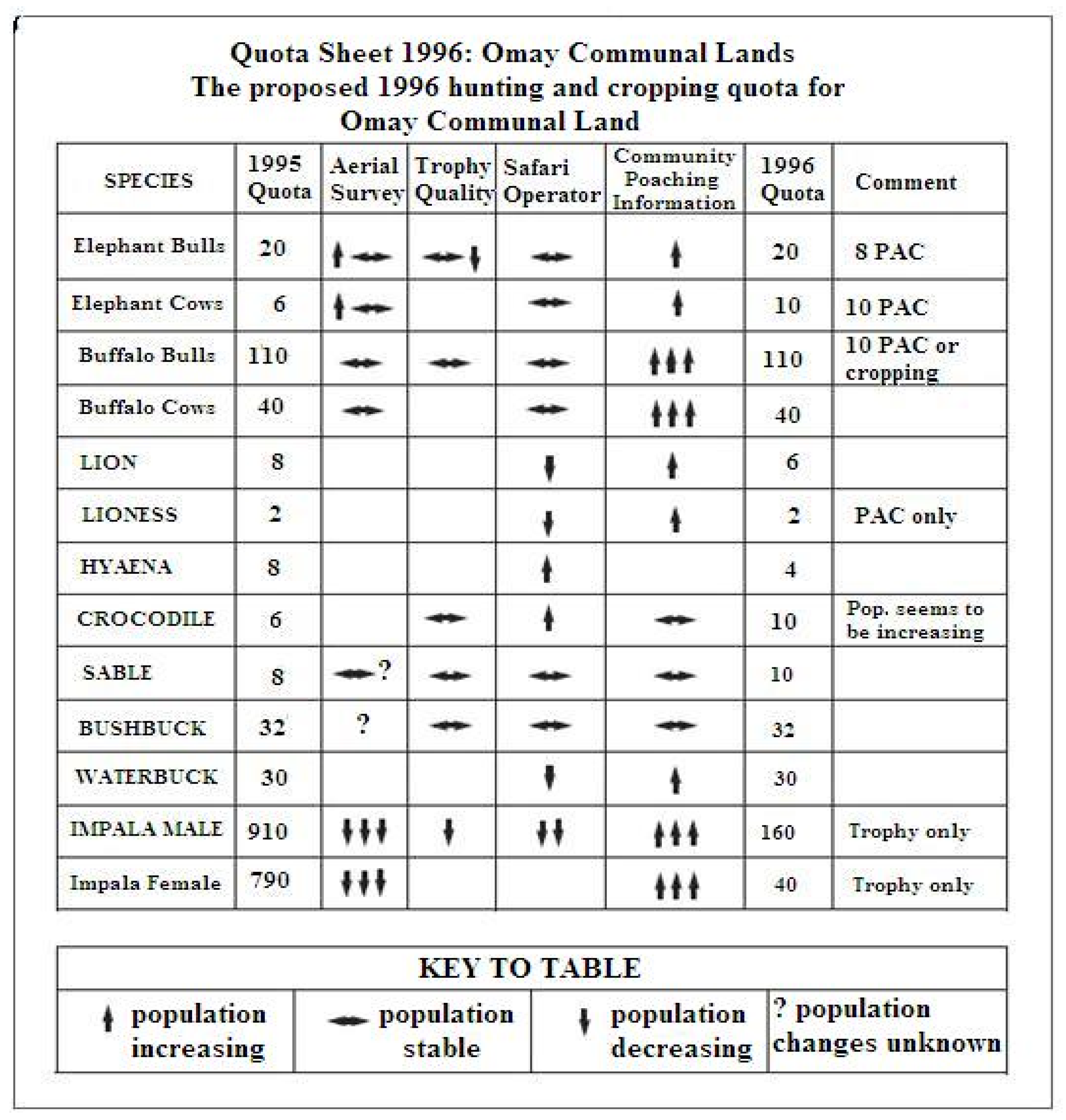

- WWF. Quota setting manual; Wildlife management series. WWF-World Wide Fund for Nature (formerly World Wildlife Fund) Program Office; Zimbabwe, Zimbabwe Trust: Harare, Zimbabwe; Safari Club International, Arizona, USA, 1997. Available online: http://www.wag-malawi.org/Quota%20Setting%20Manual.pdf (Accessed 1 August 2009).

- WWF. Counting wildlife manual; WWF-World Wide Fund for Nature (formerly World Wildlife Fund) Southern African Regional Program Office (SARPO); Zimbabwe Trust: Harare, Zimbabwe; Safari Club International, Arizona, USA, 2000. Available online: http://www.wag-malawi.org/Counting%20Wildlife.pdf (Accessed 1 August 2009).

- Hulme, D.; Taylor, R. Integrating environmental, economic and social appraisal in the real world: from impact assessment to adaptive management. In Sustainable development and integrated appraisal in a developing world; Lee, N., Kirkpatrick, C., Eds.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, I. What I tell you three times is true. Conservation, ivory, history and politics; Librario Publishing: Moray, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- DeGeorges, A. Field notes Tanzania, September 11-22. SCI African Office Manager: Pretoria, South Africa, 1999; (Unpublished). [Google Scholar]

- Hutton, J.; Adams, W.M.; Murombedzi, J.C. Back to the barriers? Changing narratives in biodiversity conservation. Forum for Development Studies. 2005, 32. Available online: http://rmportal.net/library/files/back-to-barriers.pdf/view?set_language=es (Accessed 1 August 2009).

- Jones, J. Transboundary conservation in Southern Africa: Exploring conflict between local resource access and conservation; Centre for Environmental Studies: University of Pretoria South Africa, 2003. Available online: http://www.iapad.org/publications/ppgis/jones.jennifer.pdf (Accessed 1 August 2009).

- Decolonizing nature. Strategies for conservation in a post-colonial era; Adams, W.; Mulligan, M. (Eds.) Earthscan Publications: London, UK, 2003.

- Dzingirai, V. Disenfranchisement at large transfrontier zones, conservation and local livelihoods; IUCN ROSA: Harare, Zimbabwe, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, J. Still off of the conservation map in Central Africa: Bureaucratic neglect of forest communities in Cameroon; World Rainforest Movement: Montevideo, Uruguay, 2003. Available online: http://www.wrm.org.uy/countries/Cameroon/still.html (Accessed 1 August 2009).

- Peterson, D. Eating apes; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hagberg, S. The authority and violence of a hunters’ association in Burkina Faso. “Each bird is sitting in its own tree. In Conflicts over land and water in Africa; Derman, B., Odgaard, R., Sjaastad, E., Eds.; James Curry: Oxford, UK; Michigan State University Press: East Lansing, MI, USA; University of KwaZulu-Natal Press, Pietermaritzburg: South Africa, 2007; pp. 187–201. [Google Scholar]

- Thomson, R. A game warden’s report. The state of wildlife in Africa at the start of the third millennium; Magron Publishers: Hartbeespoort, South Africa, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Norton-Griffiths, M. How many wildebeest do you need? World Economics. 2007, 8, pp. 41–64. Available online: http://mng5.com/papers/HowMany.pdf (Accessed 8 July 2009).

- Maliti, H.T. The use of GIS as a tool in wildlife monitoring in Tanzania: A case study on the impact of human activity on wildlife in the Tarangire-Manyara ecosystem; Nature Conservation in the Department of Nature Conservation Faculty of Agricultural Sciences, Tshwane University of Technology: Pretoria, South Africa, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Cumming, D. Elephantine dilemmas. Academy of Science South Africa. Quest 2005, 1, 14–17. [Google Scholar]

- Magome, H.; Fabricius, C. Reconciling biodiversity conservation with rural development: The holy grail of CBNRM. In Rights, resource and rural development. Community-based natural resource management in Southern Africa; Fabricius, C., Kock, E., Magome, H., Turner, S., Eds.; Earthscan: London, UK, 2004; pp. 93–111. [Google Scholar]

- Hara, M. Beach village committees as a vehicle for community participation: Lake Malombe/Upper Shire River participatory program. In Rights, resource and rural development. Community-based natural resource management in Southern Africa; Fabricius, C., Kock, E., Magome, H., Turner, S., Eds.; Earthscan: London, UK, 2004; pp. 182–193. [Google Scholar]

- Sasa, M. The Persian Gulf of strategic minerals of our earth. New African. 2007. Available online: http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_qa5391/is_200708/ai_n21294087/ (Accessed 1 August 2009).

- DeGeorges, A. Conservation and development. History and direction in Africa preparing for the 21st century; Prepared as final briefing document as Regional Environmental Advisor East and Southern Africa for USAID/REDSO/ESA: Nairobi, Kenya, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Schaller, G. The mountain gorilla. Ecology and behaviour; University of Chicago Press, Midway Reprint: Chicago, IL, USA; London, UK, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Wild, R.G.; Mutebi, J. Conservation through community use of plant resources. Establishing collaborative management at Bwindi Impenetrable and Mgahinga Gorilla National Parks, Uganda; People and Plants. Working Paper No. 5. UNESCO: Paris, France, 2005. Available online: http://www.peopleandplants.org/storage/working-papers/wp5e.pdf (Accessed 1 August 2009).

- Adams, W.M.; Infield, M. Community conservation at Mgahinga Gorilla National Park, Uganda; Working Paper No. 10. Community Conservation Research in Africa. Principles and Comparative Practice. Institute for Development Policy and Management, University of Manchester: Manchester, UK, 1998. Available online: http://www.conservationfinance.com/Documents/GEF%20FA%20papers/adams_and_infield.pdf (Accessed 1 August 2009).

Notes

- iThe maji or magic water reputed to prevent German bullets from killing, came from a shallow well called Kisima Mkwanga by Kingupira in the eastern Selous. The Germans applied a scorched earth policy—burning huts, laying waste and destroying crops. The Maji Maji fighters did the same against villages which did not join them [40].

- iiTsetse fly is the vector of human and bovine sleeping sickness/trypanosomiasis. Although there are trypanotolerant cattle such as the N’Dama in West Africa and the Nguni in Southern Africa, over much of Africa tsetse fly areas are dominated by wildlife over livestock.

- iiiTraditional Arab sailing vessel common off the East Africa coast.

- ivUse of the name “World Conservation Union”, in conjunction with IUCN, began in 1990. From March 2008 this name is no longer commonly used. Available online: http://www.iucn.org/about/ (Accessed July 2009).

- vA term coined by well known and widely travelled Zimbabwean professional hunter, Andy Wilkinson, who has seen this phenomenon occurring all over the wilds of rural Africa.

- vi“Open Access Resources” are those owned by the state, belonging to everyone but the responsibility of no one but the state that resulted from the imposition of centralized management systems with the coming of colonialism. For the most part this carried on after independence. The state tended/s to be incapable of controlling access by its alienated people. Africans began mining wildlife as a short-term resource in favour of long-term investments in other economic sectors over which they had control, such as farming and livestock. This is as opposed to traditional “Common Property Resources”, belonging to and managed by the community as opposed to the individual or state.

- viiWashington Consensus policies of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank that markets by themselves will lead to efficient outcomes driven by a profit motive, based on free-market fundamentalism laissez-faire policies. This included conditionalities imposed on developing countries to obtain loans, such as cutbacks in government expenditures, especially in social spending (e.g., education and health); rollback or containment of wages, privatization of state enterprises and deregulation of the economy, elimination or reduction of protection for the domestic market and less restrictions on the operations of foreign investors, successive devaluations of the local currency in the name of achieving export competitiveness, increased interest rates, and elimination of food and agricultural subsidies. The underlying intention was to minimize the role of the state. The folly of SAPs was brought out in the April 2009 G20 and the Summit of the Americas meetings, forcing the IMF to state that it will change how it relates to the developing world.

- viiiNote: Gross indicates total benefits divided among households. Often benefits never reach household, used for common property benefits and/or to run community organization (e.g., conservancy, trust, Section 21 company, association, etc.). Nett is what is left over for payment to the community for both household and/or common property benefits.

- ix(Net Profit To Company/Gross Profit) × 100

- xColumbite-Tantalite.

- xiIncome in local currency is converted to U.S. dollars, and official exchange rate adjusted for cost-of-living differences between the U.S. and country in question, allowing comparison of incomes across countries.

© 2009 by the authors; licensee Molecular Diversity Preservation International, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open-access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

DeGeorges, P.A.; Reilly, B.K. The Realities of Community Based Natural Resource Management and Biodiversity Conservation in Sub-Saharan Africa. Sustainability 2009, 1, 734-788. https://doi.org/10.3390/su1030734

DeGeorges PA, Reilly BK. The Realities of Community Based Natural Resource Management and Biodiversity Conservation in Sub-Saharan Africa. Sustainability. 2009; 1(3):734-788. https://doi.org/10.3390/su1030734

Chicago/Turabian StyleDeGeorges, Paul Andre, and Brian Kevin Reilly. 2009. "The Realities of Community Based Natural Resource Management and Biodiversity Conservation in Sub-Saharan Africa" Sustainability 1, no. 3: 734-788. https://doi.org/10.3390/su1030734

APA StyleDeGeorges, P. A., & Reilly, B. K. (2009). The Realities of Community Based Natural Resource Management and Biodiversity Conservation in Sub-Saharan Africa. Sustainability, 1(3), 734-788. https://doi.org/10.3390/su1030734