Abstract

With the continued increase in international students in China, the problem of their academic adaptation has become increasingly prominent. Analysis of the factors affecting the academic adaptation of international students and corresponding management practices can suggest measures to improve their academic adaptability. Based on grounded theory, this paper first summarizes the four main factors affecting the academic adaptation of international students, then uses structural equation modeling to construct a model of academic adaptation of international students that is tested and verified by a questionnaire survey of 2540 international students in China (51% male, 49% female). The main conclusions of this paper are as follows: (1) learning communication, course learning, and self-regulation are the main factors affecting the academic adaptation of international students, of which course learning is the most important factor; (2) academic communication and course learning have significant positive effects on self-regulation, while academic communication, course learning, and self-regulation have significant positive effects on the academic adaptation of international students; and (3) there was no significant difference in academic adaptation between genders, though there were significant differences by age. Among them, the mean score for overseas students is the largest for those older than 41 years (M = 4.79; SD = 0.33), showing that these students are most adaptable to study. Accordingly, this study advances policy suggestions for strengthening international students’ academic adaptation on the part of both universities and the government to improve the academic adaptation ability of international students in China.

1. Introduction

China has become a popular choice for international students in recent years as its economic power and influence continue to rise. By 2017, China had become the third-largest destination for overseas students worldwide and the most prominent destination in Asia [1]. With the expansion of international students in China, international education has gradually shifted from pursuing scale development to improving quality and efficiency. The promulgation of successive policy documents such as the Quality Standards for Higher International Students Education (Trial) and the Opinions of the Ministry of Education and Eight Other Departments on Accelerating the Expansion of Education Opening to the Outside World in the New Period have highlighted the urgency of “improving the quality and efficiency” of international students’ education [2]. The key to improving quality and efficiency is correctly addressing issues arising in international students’ cross-cultural academic adaptation. Cross-cultural academic adaptation is a dynamic behavior process with an internal psychological structure, psychological conditions, and realization process [3]. The academic world has yet to form a unified conceptual system of the factors affecting international students’ cross-cultural academic adaptation and the realization process. Relevant research has mainly focused on the following three aspects:

First is the influencing factors of international students’ academic adaptation, where the specific performance is at the level of colleges, individuals, and exchanges. At the university level, as the main context of international students’ studies and lives, the school’s strategic concept, activity sets, and environmental facilities impact international students’ cultural and academic adaptation [4]. Frank posited that the international education ability of colleges and universities and the daily management services of international students affect the adaptation of international students to their school’s campus culture and learning environment [5]. At the individual student’s learning level, adaptability is shaped by individual consciousness and characteristics [6]. Specifically, factors such as learning motivation, academic self-efficacy, learning strategies, Chinese proficiency, and learning ability impact the learning adaptation of overseas students in China [7]. In terms of learning communication, a harmonious teacher-student relationship, benign student-student relationships, and a harmonious class atmosphere are critical factors for international students to adapt quickly to professional learning [8].

Second is research on the current situation and problems of academic adaptation among international students. International students still face difficulties in adapting to their studies. Shen pointed out that the difficulties of academic adaptation for international students in China mainly arise from a failure to adapt to the educational form [9]. China’s education pattern differs significantly from the countries of origin of many international students in terms of teaching guarantee, curriculum setting, and training mode, so studying in China poses different degrees of difficulty in academic adaptation [10]. To meet the increasing demand of students from all over the world to study in China, China has strengthened the research and reform of study-abroad work in recent years. It is optimized for economic support, curriculum setting, training standards, and teaching support to provide adequate backup resources for international students to support academic adaptation. However, Tang believes that while suitable forms of education provide multiple forms of support and a reliable guarantee for international students’ academic adaptation, the achievement of academic adaptation also needs the initiative of international students themselves [11]. International students should actively achieve efficient and rapid academic adaptation in China through their individual efforts and group support.

Third is international students’ strategies for academic adaptation. At the macro level, international students should focus on the four educational goals of knowledge, ability, attitude, and value and reflect the concept and consciousness of cross-cultural education in the overall vision [12]. At the middle level, Pratama analyzed the current situation of the assimilation management of international students and proposed improvement strategies from the aspects of cultural concept, training mode, and global leadership to improve the assimilation management level of international students in China [13]. On the micro level, Frank pointed out that university administrators should create a more friendly campus environment for international students. Teachers should strive to improve their teaching level and intercultural communication awareness, and international students themselves should adapt to the new life with a positive attitude [5]. Generally, the strategy of academic adaptation and improvement of international students should be based on the organization of the macro vision, starting from the administrators, teachers, and students, to improve the training system. While improving the international education level, this would also promote the cross-cultural adaptation of international students.

The above studies mainly focused on academic adaptation as a part of the cross-cultural adaptation of international students from the perspective of psychology and sociology [8,10,12]. However, systematic research on international students’ academic adaptation from the pedagogy perspective is needed. In terms of research methods, the qualitative analysis of semi-structured interviews [6,13] and quantitative analysis of a questionnaire survey [9] have been adopted, and these two methods have rarely been combined. Therefore, this paper uses qualitative and quantitative research to explore the influencing factors of international students’ academic adaptation and their relationships from the pedagogy perspective to put forward targeted policy suggestions for universities and the government to improve international students’ academic adaptation.

2. Methodology

This study adopted qualitative and quantitative research methods to explore the main influencing factors of academic adaptation of international students and their internal relationships from theoretical and empirical perspectives. First, this paper adopted a qualitative research method based on grounded theory. Grounded theory is a qualitative theory proposed initially by Glaser and Strauss in The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research [14]. Cao views grounded theory as involving a procedural bottom-up establishment of substantive theory [15] based on systematic data collection to find core concepts that reflect social phenomena and then form a theory by establishing connections between these concepts. Specifically, it includes three stages: open coding, spindle coding, and selective coding [16]. The influencing factors and mechanisms of international students’ academic adaptation are complex issues involving factor identification and process interpretation [17]. Grounded theories have advantages in their application to such complex problems [18]. This study innovatively applies grounded theory to a qualitative analysis of the existing literature and interview data, enriching pedagogy research methods and broadening qualitative research fields. This paper defines the specific meaning and internal logic of the four indicators of academic adaptation, academic communication, course learning, and self-regulation through layers of coding and constructs a system of indices of international students’ academic adaptation.

This study also adopts structural equation modeling to quantitatively analyze empirical questionnaire data. The academic adaptation of international students pertains to individual subjective cognition, which is difficult to observe directly. Structural equation models allow latent variables to be inferred from multiple observed variables and can simultaneously test causal relationships among numerous latent variables [19]. The structural equation model generally consists of a measurement model and a structural model; the former represents the relationship between observed and latent variables, and the latter reflects the relationships between latent variables. The matrix equation of the structural equation model is:

where Equation (1) is the structural model, represents the endogenous latent variable, represents the exogenous latent variable, stands for the coefficient matrix, and is the error vector. Equations (2) and (3) are measurement models; is the observable variable of endogenous latent variable, refers to the factor loading matrix of endogenous latent variables and observable variables, is the observable variable of exogenous latent variable, and refers to the factor loading matrix of exogenous latent variables and observable variables.

In this study, the structural equation model is used to construct a hypothesis model of academic adaptation for international students in China. A questionnaire survey was administered to 2540 international students, based on which the hypothesis model was verified. This study mainly combines qualitative analysis based on grounded theory and quantitative research based on the structural equation to more accurately explore the academic adaptation of international students in China.

3. Index Acquisition and Hypotheses

3.1. Grounded Theory

3.1.1. Source and Selection of Data

To ensure the reliability and professional credibility of the research results, articles published on the China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI) and Web of Science were selected as the original data. The specific literature-screening criteria are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Reference selection criteria.

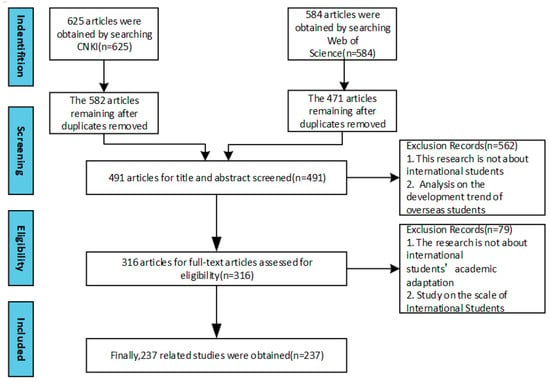

PRISMA primarily focuses on the reporting of reviews evaluating the effects of interventions but can also be used as a basis for reporting systematic reviews with other objectives [20]. The PRISMA flow diagram charts the number of records identified, included, and excluded and the reasons for the exclusion, reflecting the basis of screening more clearly and smoothly to ensure the reliability and operability of screening [21]. We used the PRISMA flow diagram to review and screen out the initially collected literature. The specific screening and review process is shown in Figure 1. Finally, 237 studies that were most relevant to the research topic were selected.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the systematic review process (PRISMA flow diagram).

3.1.2. Encoding Process

The research team collected the original data using NVivo12 qualitative analysis software, carried out top-down three-level coding for each document through the continuous coding and clustering of the text, and finally formed the conceptual model of “academic adaptation of international students in China”. The specific operations are as follows:

Initial coding required researchers to conform to the original data as much as possible with an open attitude, construct appropriate nodes, and code word by word, line by line, and event by event [16]. The author decomposed the original data layer by layer, established nodes in NVivo12 software according to the different phenomena reflected, and aggregated similar or associated codes to form initial concepts and initial categories. Through the first round of open coding, 32 first-level nodes are finally obtained, as shown in column 1 of 0.

Focused coding is an intermediate step from empirical description to analytical concept formation, which aims to analyze and compare the categories developed in the initial coding and extract the main categories [16]. Based on the original data and continued analysis at the coding node level, the comparative and inductive analysis further refined 14 s-level nodes, respectively, for teaching mode, teaching quality, teaching environment, the meaning of learning; teacher-student interaction, extracurricular communication, classroom communication; course selection, self-discipline, assignment assessment, appraisal evaluation, environmental adaptation, learning awareness, and social interaction. See column 2 of Table 2 for details.

Table 2.

Three-level coding result.

Selective coding involves selecting and integrating the concepts, categories, and relationship structures found in the first two coding stages to form a theoretical analysis model [16]. Through repeated comparison and screening, four third-level nodes were finally formed: learning communication, course learning, self-regulation, and academic adaptation, as shown in column 3 of Table 2.

3.2. Construction of the Index System

According to the results of the grounded theory analysis, the factors affecting international students’ academic adaptation mainly include academic adaptation, learning communication, course learning, and self-regulation. Of these, academic adaptation mainly includes teaching mode, teaching quality, teaching environment, and meaning of learning. Learning communication mainly includes teacher-student interaction, extracurricular communication, and classroom communication. Course learning mainly includes course selection, self-discipline, assignment assessment, and appraisal evaluation. Self-regulation mainly includes environmental adaptation, learning awareness, and social interaction. The above first- and second-level indicators constitute international students’ academic adaptation index system. The specific concepts of indicators are as follows:

(1) Academic adaptation

Four indicators can observe academic adaptation: teaching model, education quality, teaching environment, and meaning of learning. Under the current situation of convergent management, the teaching model of international students is consistent with that of domestic students [36]. However, since international students generally accept a more accessible and livelier teaching mode, domestic universities are constantly improving the education management of international students. International students’ requirements for education quality are not only reflected in whether they can complete the course assessment and meet the graduation requirements but also entail a consideration of the sense of learning and employment needs [44]. The teaching environment mainly includes teaching infrastructure and resource allocation. Sound hardware and software facilities can provide students with a quality study and life experience and promote academic adaptation [35]. Meaning of learning mainly refers to the value that international students expect to obtain during their study in China [21]. Most students look forward to mastering a skill and contributing to their country’s development while improving themselves.

(2) Learning communication

Learning communication can be observed through three indicators: teacher-student interaction, extracurricular communication, and classroom communication. The harmonious relationship between teachers and students and the timely and sufficient support of teachers are the primary factors in international students’ adapting quickly to their studies [47]. Extracurricular communication is mainly manifested in extracurricular activities such as club activities and academic exchanges. Most international students in China have their own religious beliefs and are very different from local Chinese students in living habits and ideas [43]. Therefore, whether extracurricular exchange activities can meet the tolerance of international students for multicultural habits is an essential factor affecting their participation in activities and cultural belonging. The whole dynamic balance of the classroom needs the interaction of teachers, students, and the classroom environment [49]. International students are open-minded and think outside the classroom. They need teachers’ correct guidance in class to create a multicultural classroom environment jointly.

(3) Course learning

Course learning can be measured through four indicators: course selection, self-discipline, assignment assessment, and appraisal evaluation. The Chinese proficiency of international students is uneven, and their ability and demand for professional learning are also different [33]. Therefore, their evaluations of course quantity, quality, and content directly affect their overall experience studying in China [24]. China’s higher education discipline is strict, the pace is fast, and international students will inevitably feel uncomfortable with the regulations. Under the guidance of exam-oriented education, Chinese colleges and universities generally have strict and rigid assessment systems and heavy homework [57]. At the same time, the source countries of international students advocate the flexible application of knowledge and practical ability. These two different requirements affect the performance of international students in course learning differently.

(4) Self-regulation

Self-regulation can be measured by three indicators: environmental adaptation, learning awareness, and social interaction. The source country’s social and cultural environment shapes international students’ values and behavior habits, and these environmental marks also affect the adaptation of international students to their new cultural environment [49]. As international students generally have their own dreams and goals, bearing the expectations of their families and countries, most of them cherish the opportunity to study in China and are more active in coping with difficulties in their studies and life [30]. There are significant differences in customs between the country of origin and China [56]. As international students want to integrate into China’s study and living environment as soon as possible, they must increase their interaction with Chinese students or their groups to obtain more emotional energy [43].

3.3. Research Hypotheses

According to the specific meaning of the above indicators, this section mainly analyzes the relationship between various factors and builds a hypothesis model.

Communicating with local teachers and students is the first step for international students to socialize in the new environment. Harmonious and effective communication between teachers and students and among students can directly affect international students’ positive perceptions of the new environment and enhance their adaptability to the cultural background [24]. Extracurricular communication enables international students to strengthen their knowledge of Chinese culture, which is conducive to international students understanding cultural differences, eliminating cultural barriers, and promoting the harmonious coexistence of different cultural environments. In classroom learning, the collision between and integration of different cultures and ideas of international and local students help both groups of students progress together. In cultural integration, international students can fully perceive the fun and significance of learning, adjust their learning behaviors, and increase their sense of learning efficacy [34]. International students who have just arrived in China are prone to self-isolation because of language barriers, cultural differences, personal characteristics, and other reasons. Benign academic exchanges enable international students to fully integrate into the collective life of the university while gaining professional knowledge. Through communication with others, international students can overcome their negative emotions, adjust their pace of life and learning, and adapt to the new educational and living environment [67]. Based on this, this paper posits the following hypothesis.

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

Learning communication has a significant impact on self-regulation.

The university offers as many courses as possible taking into full consideration the diverse needs and interests of international students. Having more initiative in choosing courses will help international students fully perceive the enjoyment of learning [35]. In particular, offering some local culture courses not only promotes the spread of local culture but also enables international students to learn more about the local culture and customs, which facilitates international students’ adaptation to their new environment. International students’ mastery of their coursework mainly depends on their learning attitude. International students who have high standards for themselves tend to be strict with themselves and have strong self-discipline in course learning [47]. They will constantly adjust themselves to the university courses and complete their assignments on time. They usually earn better results in the final evaluation and have a high sense of accomplishment in learning. Accordingly, this paper posits the following hypothesis.

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

Course learning has a significant impact on self-regulation.

Different social and cultural environments breed different educational environments and teaching models. In the face of cultural differences, international students can actively adjust themselves to the social and cultural environment of the country where they study and better understand its teaching methods to promote their academic adaptation [23]. At the same time, international students fully perceive the value of studying abroad to their life and have clear learning goals, which will also motivate them to constantly cope with academic pressure [55]. Different countries and nations have different cultural traditions and values, and international students go through a process of emotional, cognitive, and behavioral transformation after entering another unfamiliar culture. If international students cannot properly process and adjust their own emotions, they will feel the psychological impact of cultural differences in their environment, resulting in academic maladaptation and even weariness, truancy, dropping out of school, and other behaviors. Accordingly, this paper posits the following hypothesis.

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

Self-regulation has a significant impact on academic adaptation.

International students in unfamiliar environments often like to make friends with people from their own country or with the same religious beliefs. They are reluctant to take the initiative in communicating with Chinese teachers and classmates [40]. Due to the limitations of learning communication, it is difficult for them to quickly integrate into Chinese society. Only when their social needs are met can people feel greater social recognition and better reflect their social values. International students often turn to teachers and classmates for help when they encounter problems or difficulties. However, due to their different views on things and lack of understanding of Chinese society and culture, they are used to dealing with problems according to the concepts and standards of their own national culture [38]. When they have different opinions and poor communication with people around them, they are prone to misunderstandings, arguments, and even extreme ideas. At this point, if their basic social needs are not met, international students will suffer from intense psychological confusion and depression, which will affect their studies and overseas life. It is an important way for international students to adapt to their studies by actively adjusting their mentality and actively accepting and integrating into the new cultural environment [38]. Accordingly, this paper posits the following hypothesis.

Hypothesis 4 (H4).

Learning communication has a significant impact on academic adaptation.

The content of classroom teaching involves not only the imparting of knowledge but also the process of constructing knowledge together with teachers and students, as well as the process of multiple interactions, dialogue, and mutual learning between teachers and students. Due to the differences in the educational system, educational philosophy, and assessment system across countries, the educational level of foreign students studying in the same class is also uneven [49]. Difficulty in academic adaptation is a common problem for international students. Some international students excelled in their home countries before coming to China, but after coming to China, they find it difficult to adapt to the complicated curriculum, heavy homework, and strict assessment system, which leads to poor academic performance, and some will be dissatisfied because of China’s education model, education environment, and quality of education and fear learning and weariness [29]. In the long run, the self-efficacy of international students in the course of learning continues to decrease, resulting in a psychological gap, affecting the academic adaptation of international students in China. Accordingly, this paper posits the following hypothesis.

Hypothesis 5 (H5).

Course learning has a significant impact on academic adaptation.

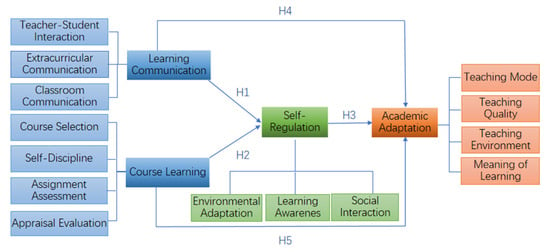

The initial model constructed according to the above assumptions is shown in Figure 2:

Figure 2.

Structural diagram of the study hypothesis.

4. Questionnaire Design and Collection

4.1. Questionnaire Design

The questionnaire scale used in this study was mainly self-compiled based on semi-structured interviews and existing questionnaires. Based on the “International Students’ Academic Adaptation” model derived from grounded theory, this study designed and prepared an interview outline comprising the four dimensions of academic adaptation, academic exchange, course learning, and self-regulation, and conducted semi-structured interviews with international students in China. Based on the semi-structured interview content, the initial questionnaire scale was designed following the questionnaire design process of Vezzani [68] and with reference to the design of academic questionnaires by Aggarwal [69]. We deleted some items irrelevant to the research topic based on the test survey data and combined other items with items from the improved scale of Aginako [70] to continue improving the scale content. In the process of creating the scale, we sought suggestions from teachers of foreign language schools in some Chinese universities and experts in the field of overseas students to improve the scale’s scientific completeness. Finally, a two-part, 18-item academic adaptation scale for international students was formed. The first part elicits the basic information of the respondents, such as age, gender, and education level. The second part is the main content of the study, comprising 14 items under the factors of academic adaptation (4 items), academic communication (3 items), course learning (4 items), and self-regulation (3 items), all scored on a five-level Likert scale to measure the different attitudes or tendencies of the respondents. Ratings include strongly disagree (1 point), disagree (2 points), unsure (3 points), agree (4 points), and strongly agree (5 points). Specific problems and reference sources are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Correlation between variables and literature sources.

4.2. Questionnaire Sampling

This study adopted the methods of stratified sampling and random sampling.

Step 1: 100 prefecture-level cities from 34 provinces and cities in China were randomly selected as the first-level sampling units.

Step 2: 300 universities in 100 prefecture-level cities were selected as the second-level sampling units.

Step 3: international colleges of 300 universities were selected as the third-level sampling units.

Step 4: students from each international college were randomly selected as the final sampling unit.

According to the sample size calculation formula N = Z2 × [p × (1 − p)]/E2, we set the confidence level as 95% (Z = 1.96), error value E = 3%, and probability value p = 0.5, yielding a calculated minimum sample size N = 1067. To ensure comprehensive and representative data of the questionnaire and in consideration of the expected number of invalid questionnaires in an actual survey, the survey group distributed a total of 3000 questionnaires (>1067 questionnaires), which were self-completed and collected by the investigators on the spot. To ensure the accuracy and completeness of the questionnaire, the collected questionnaire data were manually reviewed again to eliminate missing and invalid questionnaires, and 2540 valid samples were finally determined, for an effective response rate of 85%.

4.3. Questionnaire Quality Control

As quality control seeks to ensure data validity and is key to the analysis leading to the conclusion, we must carry out strict quality control in every link of the investigation.

Quality control of investigators: the research group selected students with serious and responsible work habits and strong English ability to participate as investigators. Simple training was conducted for each investigator to familiarize them with and help them correctly understand the contents of the questionnaire and to enable them to help the respondents to correctly understand the questions and answer them objectively. After the pre-survey and several research group meetings, the investigators were again familiarized with the survey procedure and survey content.

Quality control of questionnaire design: the questionnaire strictly followed the design procedure and design principles. To ensure the feasibility of the questionnaire, we conducted two batches of trial investigation with 50 cases in each batch to identify any shortcomings of the questionnaire design, modified and repeatedly demonstrated the feasibility of the questionnaire, and ensured its credibility.

Quality control during the field investigation: the questionnaire adopted a unified self-made method and strictly followed the relevant design procedures and principles. In the process of a formal investigation, we used the method of collecting and completing the questionnaires as we went along. After each respondent completed the questionnaire, the investigator checked the respondent’s response, found problems in a timely fashion, checked for gaps, verified the accuracy and completeness of the questionnaire as far as possible, and ensured the quality of the questionnaire with maximum validity. Finally, the questionnaire of academic adaptation for international students in China was designed, including 4 basic questions and 14 main questions.

4.4. Questionnaire Analysis

SPSS26.0 software was used for statistical analysis in this study. First, the total scores of the samples were sorted in ascending order, and the top 3% of the samples were considered the low group, while the sample with the lowest 3% of the scores was considered the high group, and then the extreme values were compared. An independent-sample t-test was then conducted, and it was found that the SIG values of the mean equation were all less than 0.005, indicating significant differences in all variables between the low group and the high group, in line with the actual situation. On this basis, the author conducted a homogeneity test for each item.

4.4.1. Reliability Test

In this study, the internal consistency method was used to test the reliability of variable measurement. The reliability of the 14 items of the questionnaire was analyzed, and the Cronbach’s α reliability coefficient of the measured variables was calculated as 0.857, which exceeded the threshold acceptable value of 0.7, indicating the high reliability of the scale.

4.4.2. Validity Test

Validity reflects the performance degree of the survey results on the content to be investigated and is divided into content validity and construct validity. To ensure that the scale met the requirements of content validity, the author referred to a large number of studies of theory and the research literature, consulted professional teachers, fully considered the facts on hand, and concluded that the questions and indicators of the questionnaire were appropriate. In this study, factor analysis was used to analyze the construction validity of the scale, for which the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) test and Bartlett sphericity test were used. The results showed that the KMO value of the scale was 0.862 (>0.8), which was close to 1, indicating that the sample size met the requirements and the data were suitable for factor analysis. The significance level value of Bartlett’s sphericity test is p = < 0.01, indicating a meaningful relationship between the original variables and that the scale data are suitable for factor analysis. In conclusion, the questionnaire has good reliability and validity and can be used effectively to investigate the academic adaptation of international students.

4.4.3. Principal Component Analysis

Principal component analysis was used to extract the factors with eigenvalues greater than 1 to cluster each dimension of international students’ academic adaptation. SPSS 26.0 software extracted four common factors, and the cumulative variance contribution rate was 76.251%. It can be considered that the four common factors extracted can effectively explain the 14 academic adaptation indicators of international students. According to the content of each factor, the four principal component factors were named academic adaptation, learning communication, course learning, and self-regulation. The component matrix and the names of each factor after output rotation are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Component matrix after rotation.

5. Results

A formal scale with reliability and validity and 2540 valid datasets were obtained through theoretical model construction and principal component analysis. Structural equation modeling was used to analyze the relationships between various factors of academic adaptation of international students in China, and the mechanism of learning communication and course learning on academic adaptation through self-regulation was studied. The revised model and influence path were obtained. At the same time, the effects of the demographic characteristics and differences in the survey samples were analyzed.

5.1. Structural Equation Modeling

5.1.1. Hypothetical Model

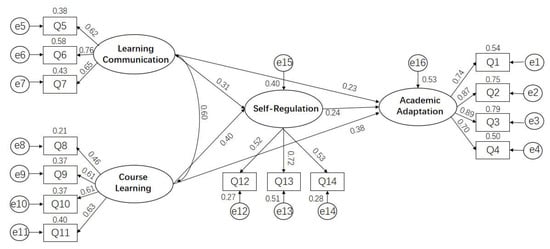

AMOS 28.0 was used for fitting the structural equation model and for the path analysis. According to the theoretical model, the subject model structure among learning communication, course learning, self-regulation, and academic adaptation was studied. Learning communication and course learning were the independent variables, self-regulation was the mediating variable, and academic adaptation was the dependent variable, and learning communication and course learning were the mediating variables of academic adaptation. The structural equations of the initial hypothetical model of four latent variables were established according to these assumptions. The operational results of the structural model are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Structural equation model diagram for initial assumptions.

The standardization results of the initial measurement model are shown in Table 5. The following goodness-of-fit indices met requirements: chi-square value/degree-of-freedom value (χ2/df) = 1.53, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = 0.051, goodness-of-fit index (GFI) = 0.929, comparative-fit index (CFI) = 0.960, parsimonious normed-fit index (PNFI) = 0.698, parsimonious goodness-of-fit index (PGFI) = 0.628, and the Tucker–Lewis index (TLI) = 0.948. However, the adjusted goodness-of-fit index (AGFI) = 0.895 and norm-fit index (NFI) = 0.894, both less than 0.9, did not meet the parameter requirements. The model fit is general, so it needs to be modified.

Table 5.

Test results of each factor of the initial model fitness.

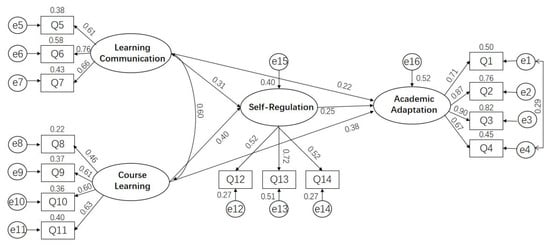

5.1.2. Modification of the Model

In this study, increasing collinearity with other indicator residuals was used to improve the degree of fit, the modification index (MI) values of the output result were observed, and the increased covariance between the two residuals with a larger MI value was noted. It was found that the MI values of e1 and e4 were 12.978, which exceeded the other values, showing that if the correlation path between the residuals of variables Q1 and Q4 is increased, the χ2-value of the model would reduce by 12.978. From a theoretical perspective, this means that students who have a deeper understanding of the meaning of learning will take the initiative to adapt to the diversified teaching models of teachers and achieve their learning goals. The better the teaching model’s adaptability, the higher the sense of learning that will be gained. To further understand the significance of learning, the two are related. Therefore, an increase in the correlation of the path between residual e1 and e4 is expected. The modified structural equation model is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

The modified structural equation model.

5.1.3. Model Checking

The standardized results of the modified structural model are shown in Table 6. The results showed as follows: χ2/df = 1.346 < 3.00, RMSEA = 0.041 < 0.08, GFI = 0.937 > 0.90, CFI = 0.974 > 0.90, NFI = 0.908 > 0.90, TLI = 0.966 > 0.90, PNFI = 0.699 > 0.50, PGFI = 0.625 > 0.50, and AGFI = 0.906 > 0.90. All of these indices meet the discrimination criteria, so the model shows a good fit to the data.

Table 6.

Model fitness test results after modification.

First, before the fit test of the comprehensive evaluation model, the model must be tested for “violation of estimates” to check whether the model fit coefficient exceeds the acceptable range. Generally, there are two test items for “violation estimation”: whether there is a negative error variance and whether the standardized coefficient exceeds or is too close to 1 [74]. On testing (Figure 4), no negative error variance was noted in the model; the absolute value of the model’s standardized coefficient was 0.22–0.90, and none of the values exceeded 0.95. Therefore, there is no “violation of estimation” in the model, and the model can be further tested for the degree of fit. Second, in terms of model fit evaluation, the higher the model fit, the higher the model availability and the more meaningful the parameter estimation. Chi-square statistics are often used to test the model fit. When the model fits the data perfectly, the difference is 0. The chi-square value of this model was 94.249, and the return probability was 0.028. Chi-square statistics are easily affected by sample size, so in addition to chi-square statistics, other fitness indicators need to be referred to at the same time. According to the data in Table 6, each statistic’s indicators were up to standard, the fit of the model was relatively satisfactory, and further research could be conducted.

5.2. Model Path Analysis Results

The path effect relationship among variables is shown in Table 7. The path analysis results show that the path of learning communication on self-regulation has CR (construct reliability values) > 1.96, p < 0.05, and the standardized estimate is significant. Therefore, Hypothesis 1, “Learning communication has a significant impact on self-regulation”, is valid. The path of the effect of course learning on self-regulation has CR = 2.436 > 1.96, p = 0.015 < 0.05, and the standardized estimate is significant. Therefore, Hypothesis 2, “Course learning has a significant effect on self-regulation”, is valid. The effect of self-regulation on the academic adaptation pathway has CR > 1.96, p < 0.05, and the standardized estimation is significant. Therefore, Hypothesis 3, “Self-regulation has a significant impact on academic adaptation”, is valid. The effect of academic communication on the academic adaptation pathway has CR = 1.996 > 1.96, p = 0.046 < 0.05, and the standardized estimation is significant. Therefore, Hypothesis 4, “Academic communication has a significant impact on academic adaptation”, is valid. The effect of course learning on the academic adaptation pathway has CR > 1.96, p < 0.05, and the standardized estimation is significant. Therefore, Hypothesis 5, “Course learning has a significant impact on academic adaptation”, is valid.

Table 7.

Model path coefficient analysis results.

5.3. Analysis of the Demographic Characteristics of the Survey Samples

5.3.1. Demographic Characteristics of the Survey Sample

The sample’s demographic characteristics mainly include the genders, ages, and education levels of the respondents. The proportions of men and women in the survey sample were 51% and 49%, respectively, showing a relatively balanced distribution. The education level of international students in China was generally high, with 59% of students having received postgraduate education or above. Most of the international students were younger, mainly under 30 years old, accounting for 81%. The distribution of majors in literature and history, science and technology, and agriculture and medicine in China were 43%, 25%, and 32%, respectively, as shown in Table 8.

Table 8.

Participants’ demographic characteristics.

5.3.2. Analysis of Differences in Demographic Factors

The difference analysis mainly focuses on demographic variables to study the effects of gender, age, education level, and other factors on the academic adaptation of international students. SPSS 26.0 was used to analyze the variables with an independent-sample t-test and one-way analysis of variance. An independent-sample t-test was used to investigate the influence of gender, and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to examine the influence of education level and age on academic adaptation.

(1) Gender

The independent-sample t-test was used to analyze the influence of gender. The test results are shown in Table 9. The significance level of international students’ gender on academic adaptation was 0.085, which is greater than 0.05. The null hypothesis of the independent-sample t-test was thus accepted. That is, there was no significant difference between international students’ gender in academic adaptation.

Table 9.

The independent sample t-test of gender in academic adaptation.

(2) Education level

The influence of education level was analyzed with one-way ANOVA. The test results are shown in Table 10. The effect of education level on the academic adaptation of international students was F = 0.025 < 0.05, indicating no significant difference in the academic adaptation of international students in this study.

Table 10.

ANOVA test of educational level in academic adaptation.

(3) Age

ANOVA was used to analyze the effects of age. The test results are shown in Table 11. The results showed significant differences in the performance of international students in different age stages in academic adaptation. The LSD post hoc test shows that the average score of international students over 41 years old was 4.79, which is larger than the average value for other ages. Therefore, international students over 41 years old from countries along the Belt and Road are significantly different from those of other ages in academic adaptation.

Table 11.

ANOVA test of age in academic adaptation.

6. Discussion

First, based on grounded theory, this study coded the existing research data and defined the specific concepts and logical relations of the influencing factors (academic adaptation, learning communication, course learning, and self-regulation) of the academic adaptation of international students in China, and constructed the Academic Adaptation Index System of International Students in China. Second, structural equation modeling was used to build a hypothesis model of academic adaptation for international students. Finally, the questionnaire was used to conduct an empirical survey of 2540 international students, and the hypothesis model was verified. The main conclusions of this study are as follows:

- (1)

- Academic communication and course learning significantly positively impact self-regulation. In previous studies of the effect of the learning mode on self-regulation ability, scholars have pointed out that positive learning behavior will promote self-regulation [75]. This study points out that positive learning behaviors, such as teacher-student academic exchanges and activities in and out of class, can also promote the positive self-regulation of international students in China. The conclusions of this study are similar to those of previous scholars, and this study holds specific theoretical and practical significance. The positive effects of academic exchange on self-regulation are as follows: through various academic exchange activities, international students can learn about China’s education model and cutting-edge knowledge and overcome their fear of unfamiliar environments. International students are fully exposed to the Chinese education environment and adjust their learning behavior to adapt to study life. The influence of course learning on self-regulation mainly comes from the degree of mastery of classroom knowledge. Interest in the course content will encourage international students to adjust their learning behavior and achieve better academic performance. International students’ self-regulation is influenced by academic communication and course learning, so colleges should start with academic activities and curriculum systems, implement attractive exchange activities, improve the curriculum training system, and promote the self-regulation of international students.

- (2)

- Academic communication, course learning, and self-regulation significantly impact international students’ academic adaptation. Self-regulation has a significant positive effect on international students’ academic adaptation. International students will inevitably have negative emotions about study and life in an unfamiliar learning environment. The abilities of self-processing, self-education, and self-growth of international students are essential to promoting academic adaptation, consistent with the views of Shirley [76]. However, that study only emphasized the importance of self-regulation in thesis learning, ignoring the impact of self-regulation on the academic adaptation process as a whole. Based on the importance of self-regulation factors in the study-abroad period, this study investigates the mechanism whereby academic communication and course learning affect academic adaptation. Academic communication has a significant positive impact on international students’ academic adaptation. High-level, multi-level academic communication activities can help students better understand the educational environment in China. Academic exchange involves the collision of ideas and the integration of cultures, and multi-cultural integration is promoted to improve the cross-cultural academic adaptation of international students. Course learning has a significant positive impact on international students’ academic adaptation. Studying cultural courses is the primary task for international students when they first come to China. Whether they obtain satisfactory academic results and graduate smoothly is a critical aspect of the success of their academic adaptation. The academic adaptation of international students is influenced by academic communication, course learning, and self-regulation. Therefore, to improve the degree of academic adaptation of international students, we must fully recognize the interaction between different influencing factors. Colleges and universities should take overall consideration of the individual characteristics of international students and the differences in the educational environment and increase their cultural identity and sense of belonging through extracurricular exchange activities, classroom knowledge learning, and the subjective initiative of international students to adapt to their new learning and living environment.

- (3)

- There is no significant difference in the academic adaptation of overseas students regarding gender and education level, but there is a significant age difference. This study found that the academic adaptability of overseas students over 41 years old was significantly higher than that of students in other age groups. Noor-Azniza empirically analyzed the moderating effects of gender and age on the academic adaptation of first-year students, and although he did not find a moderating effect of sex, consistent with the findings in this paper, he found that students over the age of 26 had better academic adaptation than younger students. Based on this, this paper subdivided the age range and determined that international students over 41 had better academic adaptation than those in other age groups [77]. Based on the current situation of studying abroad and previous studies, we posit that overseas students over the age of 41 have strong adaptability for the following two reasons: first, most overseas students over the age of 41 have a stable life without too much pressure, are better resistant to external temptations, and can devote themselves to their studies [78]; second, students over 41 years old have clear goals and look forward to the experience of studying in China, which can help them acquire skills and broaden their horizons [79] to help them bring China’s rapidly developing technologies and ideas to their own country and promote cultural exchanges between the two sides while helping the home country’s development [80]. Therefore, to improve international students’ overall adaptation level, colleges and universities should focus on cultivating young international students’ adaptability and guiding study and life. At the same time, the government should increase financial support, improve the scholarship policy, and resolve the worries of overseas students’ lives.

7. Suggestions

According to the above analysis, international students’ academic adaptability is mainly affected by academic communication, course learning, and self-regulation, and academic communication and course learning further affect international students’ self-regulation ability. In addition, based on the demographic analysis, older international students have a higher level of academic adaptation. Accordingly, we advance the following four suggestions for universities and the government to improve the academic adaptability of international students in China.

First, overall consideration should be given to the learning of harmonious and unified knowledge and the cultural exchange of international students in China. Given the influence of the above academic exchanges on the academic adaptability of international students, colleges and universities should actively encourage and organize the participation of international students in multicultural exchange activities and cultivate their cross-cultural communication abilities, strengthen their understanding of professional knowledge and Chinese culture in academic exchanges, and enhance their identification with Chinese culture while improving their professional knowledge.

Second, we should pioneer and establish innovative training programs and curriculum systems suitable for international students. Given the above courses’ influence on international students’ academic adaptation, colleges and universities should develop characteristic training programs based on the actual situation of international students’ professional foundation, learning objectives, and learning abilities. The organization of course content, the design of teaching methods, and the implementation of assessment and evaluation should be considered comprehensively to improve the cross-cultural adaptability of international students while cultivating their professional abilities.

Third, a two-pronged approach should be taken that emphasizes the unity of teachers’ positive guidance ability and students’ self-regulation ability. Given the impact of self-regulation on international students’ academic adaptation, colleges and universities should guide international students to exert their subjective initiative and carry out self-regulation and self-regulation based on academic exchanges and course learning. Teachers are the key to the implementation of curriculum learning and human education. Teachers’ professional levels and cultural accomplishments will directly affect international students’ professional learning and self-realization. Therefore, professional teachers and counselors should fully support international students in their studies and lives, understand their difficulties in life and psychological changes, help them perform positive self-regulation, and promote their academic and cultural adaptability.

Fourth, improved policies should be implemented to help international students devote themselves to studying and to enhance the internationalization of education. Given the poor academic adaptability of young international students in China, the government should increase financial support for international students, improve the relevant scholarship and grant policies, and reduce the living pressure on international students so they can devote themselves to their studies. Universities should also actively explore a more dynamic international education management system to provide support for the management services of the younger generation of students coming to China.

Through a combination of qualitative and quantitative analysis, this study comprehensively analyzed the influencing factors of international students’ academic adaptation and the relationships between them. Given the mechanism inferred of how the influencing factors interact, this paper advances suggestions on the adaptation strategies of international students from the perspectives of universities and the government. It expands the research methods for studying international students and provides recommendations and references for the education management of international students. However, this study still has the following limitations. First, this study only selected four dimensions and 14 representative indicators for the academic adaptation system of international students in China, and the number of respondents is limited. Second, this study only screened the literature from 2010 to 2021 for encoding, and the types and time ranges of the encoded data were limited. Third, this study was only carried out in institutions of higher learning in China. Subsequent studies should expand the scope of research, obtain data from other countries and regions, and improve the research conclusions.

Author Contributions

J.Z. contributed to the analysis and interpretation of data for the study. M.G. and J.L. wrote the first draft of the manuscript. L.Y. designed the framework for this study. S.X. and M.W. contributed to the acquisition of data for this study. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This paper reports research results of the Anhui Provincial Key Teaching and Research Project (Junqi Zhu, 2020JYXM0453), Anhui Province Economics Principle Teaching Demonstration Course Project (Junqi Zhu, 2020SJJXSFK0832), the National Social Science Foundation General Project (Ming Wan, BGA170045), and Comprehensive Practical Education Base of “Youth and Innovation Education” for college students (Jie Li, sztsjh2019-1-5).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Requests for datasets can be sent to Mengdi Gu, gumengdi0115@163.com.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Zeng, C. Strategic Management and Development Trend of Sino-foreign Cooperative University in the New Era of Open Education Development. Bp. Int. Res. Critics Linguistics Educ. (BirLE) J. 2020, 3, 919–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, J.; Nyland, B. Internationalisation of Higher Education and Global Learning: Australia and China; Sense Publishers: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.Y.; Jia, Z.C. A study on cross-cultural adaptation of international students in china—A case study of central asian students in xinjiang. J. Minzu Univ. China (Philos. Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2014, 41, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokhothu, T.M.; Callaghan, C.W. The management of the international student experience in the South African context: The role of sociocultural adaptation and cultural intelligence. Acta Commer. 2018, 18, a499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larbi, F.O.; Fu, W. Practices and challenges of internationalization of higher education in China; international students’ perspective. Int. J. Comp. Educ. Dev. 2017, 19, 78–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bittencourt, T.; Johnstone, C.; Adjei, M.; Seithers, L. “We See the World Different Now”: Remapping Assumptions about International Student Adaptation. J. Stud. Int. Educ. 2019, 25, 35–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krsmanovic, M. Encountering American higher education: First-year academic transition of international undergraduate students in the United States. J. Glob. Educ. Res. 2022, 6, 148–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozina, A.; Veldin, M.; Rožman, M.; Jugović, I.P. The mediating effect of student-teacher relationships for the relationship between empathy and aggression: Insights from Slovenia and Croatia. Curr. Psychol. 2022, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, W.; Liu, S.; Schuetze, H.G.; Jung, J.; Li, K. Globalization and transnational academic mobility: The experiences of chinese academic returnees. Qiongqiong Chen. Front. Educ. China 2017, 12, 296–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preston, J.P.; Wang, A. The academic and personal experiences of Mainland Chinese students enrolled in a Canadian Master of Education Program. Int. J. Comp. Educ. Dev. 2017, 19, 177–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, J.; Ren, W. Advanced learners’ responses to chinese greetings in study abroad. IRAL—Int. Rev. Appl. Linguist. Lang. Teach. 2021, 60, 1173–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.; Zhou, X. Acculturation theory and the practical approaches to cross-cultural inclusiveness in international cooperation. Academics 2017, 12, 271–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratama, I.D. Active learning strategies in teaching cross cultural understanding for english education students. Universitas Islam Sultan Agung, Semarang. EduLite: J. Engl. Educ. Lit. Cult. 2017, 2, 303–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Diehl, A.; Abdul-Rahman, A.; Bach, B.; El-Assady, M.; Kraus, M.; Laramee, R.S.; Keim, D.A.; Chen, M. Characterizing grounded theory approaches in visualization. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2203.01777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Cao, W.; Bao, Y. Product intellectualization ecosystem: A framework through grounded theory and case analysis. Int. J. Emerg. Mark. 2021, 17, 1030–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hook, N. Grounded Theory; ETC Press: Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 2015; ISBN 978-1-312-88473-1. [Google Scholar]

- Gavilan, D.; Martinez-Navarro, G. Exploring user’s experience of push notifications: A grounded theory approach. Qual. Mark. Res. Int. J. 2022, 25, 233–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badong-Badilla, J.B. Being a lay partner in jesuit higher education in the philippines: A grounded theory application. Int. J. Educ. Pedagog. Sci. 2017, 11, 400–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badri, M.; Alnuaimi, A.; Yang, G.; Al Rashidi, A.; Al Sumaiti, R. A Structural Equation Model of Determinants of the Perceived Impact of Teachers’ Professional Development—The Abu Dhabi Application. SAGE Open 2017, 7, 2158244017702198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGowan, J.; Straus, S.; Moher, D.; Langlois, E.V.; O’Brien, K.K.; Horsley, T.; Aldcroft, A.; Zarin, W.; Garitty, C.M.; Hempel, S.; et al. Reporting scoping reviews—PRISMA ScR extension. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2020, 123, 177–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahale, L.A.; Elkhoury, R.; El Mikati, I.; Pardo-Hernandez, H.; Khamis, A.M.; Schünemann, H.J.; Haddaway, N.R.; Akl, E.A. PRISMA flow diagrams for living systematic reviews: A methodological survey and a proposal. F1000Research 2021, 10, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dincel, B.K. The Opinions of Turkish Learning Foreign Students about the Educational System in Turkey and Their Respective Countries, Turkish Language and the Language Areas. Int. Educ. Stud. 2019, 12, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nataliia, M.; Inna, V. Interactive Methods of Teaching the Humanities in Higher Education Institutions. Int. J. Manag. Humanit. 2020, 4, 53–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, W.H. Understanding the process of internationalization of curriculum studies in China: A case study. TCI (Transnatl. Curric. Inq.) 2016, 13, 56–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; He, Y.; Xia, Z. The effect of perceived discrimination on cross-cultural adaptation of international students: Moderating roles of autonomous orientation and integration strategy. Curr. Psychol. 2022, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilshad, S.; Malik, S. Cultural Adjustment of Foreign Students in the Era of Globalization (A Case Study at Iiui-pakistan). Am. J. Educ. Res. 2019, 7, 853–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guedes, G.F.; Cavalcante, I.M.D.S.; Püschel, V.A.D.A. International academic mobility: The experience of undergraduate nursing students. Rev. Esc. Enferm. USP 2018, 52, e03358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y. Study Abroad Experience and Career Decision-Making: A Qualitative Study of Chinese Students. Front. Educ. China 2020, 15, 313–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.K.N. Sustainable supervisory relationships between postgraduate international students and supervisors: A qualitative exploration at a Malaysian research university. Stud. Grad. Postdr. Educ. 2022, 13, 188–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonio, A.L.; Baek, C. Beyond survey measures: Exploring international male graduate students’ sense of belonging in electrical engineering. Stud. Grad. Postdr. Educ. 2021, 13, 132–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otike, F.; Bouaamri, A.; Barát, H. Perception of international students on the role of university library during COVID-19 lockdown in Hungary. Libr. Manag. 2022, 43, 334–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yılmaz, K.; Temizkan, V. The Effects of Educational Service Quality and Socio-Cultural Adaptation Difficulties on International Students’ Higher Education Satisfaction. SAGE Open 2022, 12, 21582440221078316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J. Analysis of teaching reform of international finance course in application-oriented undergraduate colleges and universities: Taking economics college of changchun university as an example. High. Educ. Soc. Sci. 2018, 14, 23–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Dai, K. Foreign-born Chinese students learning in China: (Re)shaping intercultural identity in higher education institution. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2020, 80, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borràs, J.; Llanes, A. Investigating the impact of a semester-long study abroad program on L2 reading and vocabulary development. Study Abroad Res. Second. Lang. Acquis. Int. Educ. 2021, 6, 276–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beregovaya, O.A.; Lopatina, S.S.; Oturgasheva, N.V. Tutor Support as a Tool of Social-Cultural Adaptation ofInternational Students in Russian Universities. Vyss. Obraz. V Ross. = High. Educ. Russ. 2020, 29, 156–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulker, N. Prior learning experiences and academic life in the USA in different voices: The case of Turkish international dual-diploma students. Res. Post-Compuls. Educ. 2020, 25, 149–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clagett, J. Transformational Geometry and the Central European Baroque Church. In Architecture and Mathematics from Antiquity to the Future; Birkhäuser: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 231–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resch, K.; Hörr, B.; Netenjakob, I.T.; Varhegyi, V.; Manarte, J.; Migdał, A.M. Silent Protest: Cross-Cultural Adaptation Processes of International Students and Faculty. Int. J. Divers. Educ. 2021, 21, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubtsova, A. Socio-linguistic innovations in education: Productive implementation of intercultural communication. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 497, 012059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabó, A.; Papp, Z.Z.; Luu, L.A.N. Social contact configurations of international students at school and outside of school: Implications for acculturation orientations and psychological adjustment. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2020, 77, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Chikwa, G. An Exploration of China-Africa Cooperation in Higher Education: Opportunities and Challenges in Open Distance Learning. Open Prax. 2021, 13, 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, A. A good career start can open doors: The plusses and minuses of an international graduate student program—A student’s perspective. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 2020, 209, 225–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pownall, I. Student identity and group teaching as factors shaping intention to attend a class. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2012, 10, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazanfari, M.; Barani, G.; Rokhsari, S. An Investigation into Metadiscourse Elements Used by Native vs. Non-native University Students across Genders. Iran. J. Appl. Lang. Stud. 2018, 10, 61–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Quanjiang, G.; Michael, L.; Chun, L.; Chuang, W. Developing literacy or focusing on interaction: New Zealand students’ strategic efforts related to Chinese language learning during study abroad in China. System 2021, 98, 102462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J. Chinese overseas students and intercultural learning environments: Academic adjustment, adaptation and experience. Front. Educ. China 2018, 13, 658–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikula, P.-T.; Sibley, J. Supporting international students’ academic acculturation and sense of academic self-efficacy. Transit. J. Transient Migr. 2020, 4, 137–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polyzou, A.; Kalantzi, M.; Karypis, G. Faireo: User group fairness for equality of opportunity in course recommendation. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2109.05931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi-Ran, K. Research on Writing Tasks for International Students. Educ. J. 2021, 10, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davydova, Z.; Balyuk, O.; Kurbanova, D. Information Adaptation of International University Students Under the Conditions of Multicultural Educational Environment. J. Sociol. Anthropol. 2018, 2, 90–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naveh, G.; Shelef, A. Analyzing attitudes of students toward the use of technology for learning: Simplicity is the key to successful implementation in higher education. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 2020, 35, 382–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claro, P.B.; Esteves, N.R. Teaching sustainability-oriented capabilities using active learning approach. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2021, 22, 1246–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamitewoko, E. International Students Labour and School Attendance: Evidence from China. Theor. Econ. Lett. 2021, 11, 962–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, I.N.E.-D. Raising Undergraduate Students’ Level of Academic Readiness through Teaching Intercultural Communication. Adv. J. Commun. 2022, 10, 209–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, M.; Lu, G.; Yin, H.; Li, L. Student Engagement for Sustainability of Chinese International Education: The Case of International Undergraduate Students in China. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C. A study of college teacher assessment systems in china and the united states. High. Educ. Soc. Sci. 2017, 12, 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Othman, I.W.; Yusoff, M.S.; Shah, M.K.M.; Ationg, R.; Esa, M.S.; Yakin, H.S.M. The health enhancement impact of self assimilation in academic achievement amongst international students in malaysian public universities. Sys. Rev. Pharm. 2021, 12, 540–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fute, A.Z. The Danger of Acculturation Process Phase to International Students’ Academic Achievement: A Case Study of Zhejiang Normal University. Asian J. Educ. Soc. Stud. 2020, 12, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rennasuzuki, O. The effects of a short-term study-abroad program on students’ english proficiency and intercultural adaptability. Bull. St. Margarets 2017, 37, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angraini, Y. Cross-culture analysis: Cultural adaptation and nonverbal communication in non-native english-speaking countries. ANGLO-SAXON J. Engl. Lang. Educ. Study Program 2018, 8, 239–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.-G. Role of Social Media in Cross-Cultural Settings to Foster Individual Creativity: An Empirical Research in China; DEStech Publications: Lancaster, PA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumura, S. The impact of predeparture instruction on pragmatic development during study abroad. Study Abroad Res. Second. Lang. Acquis. Int. Educ. 2022, 7, 152–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karay, Y.; Restel, K.; Marek, R.; De Castro, B.S. Studienstart International of the University of Cologne: The closely supervised semester of study entry for students from third countries using the example of the model degree program for human medicine. GMS J. Med. Educ. 2018, 35, Doc60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, H. Study on the psychological depression of international students in china: Taking x university in ningxia as an example. Can. Soc. Sci. 2019, 15, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.T.; Liu, C.Y.; Hu, Z.S.; Lii, S.C. The impact of medical students’ academic achievement, student club participation, and meaning of life on depression and anxiety in taiwan. Med. Educ. 2019, 23, 175–184. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, M. The reschematization of face in Chinese overseas students’ intercultural experience. Int. J. Lang. Cult. 2022, 9, 27–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vezzani, C.; Vettori, G.; Pinto, G. Assessing students’ beliefs, emotions and causal attribution: Validation of ‘Learning Conception Questionnaire’. South Afr. J. Educ. 2018, 38, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Aggarwal, M.; Sharma, A.; Singh, P.; Bansal, P. Impact of structured verbal feedback module in medical education: A questionnaire- and test score-based analysis. Int. J. Appl. Basic Med. Res. 2016, 6, 220–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aginako, Z.; Peña-Lang, M.B.; Bedialauneta, M.T.; Guraya, T. Analysis of the validity and reliability of a questionnaire to measure students’ perception of inclusion of sustainability in engineering degrees. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2021, 22, 1402–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kizu, M.; Gyogi, E.; Dougherty, P. Epistemic stance in L2 English discourse. Appl. Pragmat. 2022, 4, 33–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azila-Gbettor, E.M.; Mensah, C.; Abiemo, M.K. Self-efficacy and academic programme satisfaction: Mediating effect of meaningfulness of study. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 2022, 36, 261–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imran, H.M.; Shoaib, M.; Ghaffari, A.S. The relationship between acculturative stress, depression, anxiety and religious coping among international students in china. Int. J. Curr. Res. 2020, 12, 15253–15257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vowels, M.J. Maximizing statistical power in structural equation models by leveraging conditional independencies. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2203.13331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okmen, B.; Kilic, A. The Effect of Layered Flipped Learning Model on Students’ Attitudes and Self-Regulation Skills. Int. J. Res. Educ. Sci. 2020, 6, 409–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miedijensky, S.; Lichtinger, E. Seminar for Master’s Thesis Projects: Promoting Students’ Self-Regulation. Int. J. High. Educ. 2016, 5, 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noor-Azniza, I.; Malek, T.J.; Ibrahim, Y.S.; Farid, T.M. Moderating Effect of Gender and Age on the Relationship between Emotional Intelligence with Social and Academic Adjustment among First Year University Students. Int. J. Psychol. Stud. 2011, 3, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ali, A.S.M.; Ahmad, R. The impact of social media on international students: Cultural and academic adaptation. J. Eng. Appl. Sci. 2018, 13, 546–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadeem, M.U.; Mohammed, R.; Dalib, S.; Mumtaz, S. An investigation of factors influencing intercultural communication competence of the international students from a higher education institute in Malaysia. J. Appl. Res. High. Educ. 2021, 14, 933–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, A.; Beri, N. Acculturative stress among international students in relation to gender, age and family income. Sch. Res. J. Interdiscip. Stud. 2017, 4, 10529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).