Impact of Tongue Piercings on Oral Health: A Narrative Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Dental Trauma

4.2. Gingival and Mucosa Trauma

4.3. Risk of Hemorrhage

4.4. Tissue Overgrowth

4.5. Localized Infections

4.6. Systemic Infections

4.7. Ingested Piercing

4.8. Limitations of the Review

4.9. Recommendations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Stirn, A. Body piercing: Medical consequences and psychological motivations. Lancet 2003, 361, 1205–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Covello, F.; Salerno, C.; Giovannini, V.; Corridore, D.; Ottolenghi, L.; Vozza, I. Piercing and Oral Health: A Study on the Knowledge of Risks and Complications. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Koch, J.R.; Roberts, A.E.; Armstrong, M.L.; Owen, D.C. Religious belief and practice in attitudes toward individuals with body piercing. Psychol. Rep. 2004, 95, 583–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davidson, L. Africa adorned: Body image and symbols of physical beauty. J. Am. Acad. Psychoanal. Dyn. Psychiatry 2010, 38, 255–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desai, N.; Breuner, C.C. Tattoos and Piercings in Female Adolescents and Young Adults. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Gynecol. 2023, 36, 14–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breuner, C.C.; Levine, D.A.; Committee on Adolescence. Adolescent and Young Adult Tattooing, Piercing, and Scarification. Pediatrics 2017, 140, e20163494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perry, M.; Lewis, H.; Thomas, D.R.; Mason, B.; Richardson, G. Need for improved public health protection of young people wanting body piercing: Evidence from a look-back exercise at a piercing and tattooing premises with poor hygiene practices, Wales (UK) 2015. Epidemiol. Infect. 2018, 146, 1177–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Preslar, D.; Borger, J. Body Piercing Infections; [Updated 10 July 2023]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537336/ (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Malcangi, G.; Patano, A.; Palmieri, G.; Riccaldo, L.; Pezzolla, C.; Mancini, A.; Inchingolo, A.D.; Di Venere, D.; Piras, F.; Inchingolo, F.; et al. Oral Piercing: A Pretty Risk—A Scoping Review of Local and Systemic Complications of This Current Widespread Fashion. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dayakar, M.M.; Dayakar, A.; Akbar, S.M. Elective tongue piercing: Fad with fallout. J. Cutan. Aesthet. Surg. 2015, 8, 71–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Clapham, E.; Crooke, J. The patient with a pierced tongue. J. Perioper. Pract. 2011, 21, 156–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, B.K.; Lee, H.Y. Self-esteem, propensity for sensation seeking, and risk behaviour among adults with tattoos and piercings. J. Public Health Res. 2017, 6, 1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ibraheem, W.I.; SPreethanath, R.; Devang Divakar, D.; Al-Askar, M.; Al-Kheraif, A.A. Effect of tongue piercing on periodontal and peri-implant health: A cross-sectional case-control study in adults. Int. J. Dent. Hyg. 2022, 20, 282–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plessas, A.; Pepelassi, E. Dental and periodontal complications of lip and tongue piercing: Prevalence and influencing factors. Aust. Dent. J. 2012, 57, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stead, L.R.; Williams, J.V.; Williams, A.C.; Robinson, C.M. An investigation into the practice of tongue piercing in the South West of England. Br. Dent. J. 2006, 200, 103–107; discussion 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapferer, I.; Beier, U.S.; Persson, R.G. Tongue piercing: The effect of material on microbiological findings. J. Adolesc. Health 2011, 49, 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Botchway, C.; Kuc, I. Tongue piercing and associated tooth fracture. J. Can. Dent. Assoc. 1998, 64, 803–805. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Giuca, M.R.; Pasini, M.; Nastasio, S.; D’ Ercole, S.; Tripodi, D. Dental and periodontal complications of labial and tongue piercing. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. Agents 2012, 26, 553–560. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Offen, E.; Allison, J.R. Do oral piercings cause problems in the mouth? Evid. Based Dent. 2022, 23, 126–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.; Wang, D.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, C.; Ren, J.; Xu, K.; Deng, M.; Tian, G.; Ding, C.; Cao, Q.; et al. Transmission of Hepatitis B and C Virus Infection Through Body Piercing: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Medicine 2015, 94, e1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Vozza, I.; Fusco, F.; Corridore, D.; Ottolenghi, L. Awareness of complications and maintenance of oral piercing in a group of adolescents and young Italian adults with intraoral piercing. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Cir. Bucal 2015, 20, e413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberholzer, T.G.; George, R. Awareness of complications of oral piercing in a group of adolescents and young South African adults. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endod. 2010, 110, 744–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farah, C.S.; Harmon, D.M. Tongue piercing: Case report and review of current practice. Aust. Dent. J. 1998, 43, 387–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brennan, M.; O’Connell, B.; O’Sullivan, M. Multiple dental fractures following tongue barbell placement: A case report. Dent. Traumatol. 2006, 22, 41–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shinohara, E.H.; Horikawa, F.K.; Ruiz, M.M.; Shinohara, M.T. Tongue piercing: Case report of a local complication. J. Contemp. Dent. Pract. 2007, 8, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zadik, Y.; Sandler, V. Periodontal attachment loss due to applying force by tongue piercing. J. Calif. Dent. Assoc. 2007, 35, 550–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berenguer, G.; Forrest, A.; Horning, G.M.; Towle, H.J.; Karpinia, K. Localized periodontitis as a long-term effect of oral piercing: A case report. Compend. Contin. Educ. Dent. 2006, 27, 24–27; quiz 28, 36. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Correa, F.O.; Krüger, M.S.; Silveira, F.M.; Martins, T.M.; Ahmed, H.B.; Javed, F. Severe alveolar bone loss around the mandibular incisor teeth as a long-term effect of tongue-piercing. J. Coll. Physicians Surg. Pak. 2014, 24, 375–376. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bajkin, B.; Babic, I.; Petrovic, B.; Markovic, D. Substantial bone loss in the mandibular central incisors area as a complication of tongue piercing: A case report. Eur. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2014, 15, 75–77. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Albeshri, S.; Tarnow, D.P.; Kang, P. Successful Regenerative Therapy of Periodontal Defects Associated with Tongue Piercing: A Clinical Report. Compend. Contin. Educ. Dent. 2024, 45, 204–208. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kretchmer, M.C.; Moriarty, J.D. Metal piercing through the tongue and localized loss of attachment: A case report. J. Periodontol. 2001, 72, 831–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shacham, R.; Zaguri, A.; Librus, H.Z.; Bar, T.; Eliav, E.; Nahlieli, O. Tongue piercing and its adverse effects. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endod. 2003, 95, 274–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Jornet, P.; Camacho-Alonso, F.; Pons-Fuster, J.M. A complication of lingual piercing: A case report. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endod. 2005, 99, E18–E19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fleming, P.S.; Flood, T.R. Bifid tongue—A complication of tongue piercing. Br. Dent. J. 2005, 198, 265–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patussi, C.; Sassi, L.M.; Da Silva, W.P.; Zavarez, L.B.; Schussel, J.L. Oral Pyogenic Granuloma after Tongue Piercing Use: Case Report. Dentistry 2014, 4, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özdemir, D.L.; Kef, K. A Rising Concern: A Case of Perforation of The Floor of The Mouth Caused by Tongue Piercing. Turk. Med. Stud. J. 2018, 5, 47–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennequin-Hoenderdos, N.L.; Slot, D.E.; Van der Weijden, G.A. The incidence of complications associated with lip and/or tongue piercings: A systematic review. Int. J. Dent. Hyg. 2016, 14, 62–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plastargias, I.; Sakellari, D. The consequences of tongue piercing on oral and periodontal tissues. ISRN Dent. 2014, 2014, 876510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Theodossy, T. A complication of tongue piercing. A case report and review of the literature. Br. Dent. J. 2003, 194, 551–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maheu-Robert, L.F.; Andrian, E.; Grenier, D. Overview of complications secondary to tongue and lip piercings. J. Can. Dent. Assoc. 2007, 73, 327–331. [Google Scholar]

- Ziebolz, D.; Stuehmer, C.; van Nüss, K.; Hornecker, E.; Mausberg, R.F. Complications of tongue piercing: A review of the literature and three case reports. J. Contemp. Dent. Pract. 2009, 10, E065–E071. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- De Moor, R.J.G.; De Witte, A.M.J.C.; De Bruyne, M.A.A. Tongue piercing and associated oral and dental complications. Dent. Traumatol. 2000, 16, 232–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassiouny, M.A.; Deem, L.R.; Deem, T.E. Tongue piercing: A restorative perspective. Quintessence Int. 2001, 32, 477–481. [Google Scholar]

- DiAngelis, A.J. The lingual barbell: A new etiology for the cracked-tooth syndrome. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 1997, 128, 1438–1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ram, D.; Peretz, B. Tongue piercing and insertion of metal studs: Three cases of dental and oral consequences. ASDC J. Dent. Child. 2000, 67, 326–329, 302. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, A.; Moore, A.; Williams, E.; Stephens, J.; Tatakis, D.N. Tongue piercing: Impact of time and barbell stem length on lingual gingival recession and tooth chipping. J. Periodontol. 2002, 73, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Moor, R.J.; De Witte, A.M.; Delme, K.I.; De Bruyne, M.A.; Hommez, G.M.; Goyvaerts, D. Dental and oral complications of lip and tongue piercings. Br. Dent. J. 2005, 199, 506–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amato, A.; Martina, S.; De Benedetto, G.; Michelotti, A.; Amato, M.; Di Spirito, F. Hypersensitivity in Orthodontics: A Systematic Review of Oral and Extra-Oral Reactions. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 4766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Di Spirito, F.; Amato, A.; Di Palo, M.P.; Ferraro, R.; Cannatà, D.; Galdi, M.; Sacco, E.; Amato, M. Oral and Extra-Oral Manifestations of Hypersensitivity Reactions in Orthodontics: A Comprehensive Review. J. Funct. Biomater. 2024, 15, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Reynolds, M.A. Gingival recession is likely associated with tongue piercings. J. Evid. Based Dent. Pract. 2012, 12 (Suppl. 3), 145–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Escudero-Castaño, N.; Perea-García, M.A.; Campo-Trapero, J.; Cano-Sánchez Bascones-Martínez, A. Oral and perioral piercing complications. Open Dent. J. 2008, 2, 133–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Rangeeth, B.N.; Moses, J.; Reddy, V.K. A rare presentation of mucocele and irritation fibroma of the lower lip. Contemp. Clin. Dent. 2010, 1, 111–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Rathva, V.J. Traumatic fibroma of tongue. BMJ Case Rep. 2013, 2013, bcr2012008220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Boardman, R.; Smith, R.A. Dental implications of oral piercing. J. Calif. Dent. Assoc. 1997, 25, 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardee, P.S.; Mallya, L.R.; Hutchison, I.L. Tongue piercing resulting in hypotensive collapse. Br. Dent. J. 2000, 188, 657–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López Jornet, P.; Vicente Ortega, V.; Yáñez Gascón, J.; Cozar Hidalgo, A.; Pérez Lajarín, L.; García Ballesta, C.; Alcaraz Baños, M. Clinicopathological characteristics of tongue piercing: An experimental study. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 2004, 33, 340–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masood, M.; Walsh, L.J.; Zafar, S. Oral complications associated with metal ion release from oral piercings: A systematic review. Eur. Arch. Paediatr. Dent. 2023, 24, 677–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- de Santana Santos, T.; Martins-Filho, P.R.; Piva, M.R.; de Souza Andrade, E.S. Focal fibrous hyperplasia: A review of 193 cases. J. Oral Maxillofac. Pathol. 2014, 18 (Suppl. 1), S86–S89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Domingo, M.G.; Ferrari, L.; Aguas, S.; Alejandro, F.S.; Steimetz, T.; Sebelli, P.; Olmedo, D.G. Oral exfoliative cytology and corrosion of metal piercings. Tissue implications. Clin. Oral Investig. 2019, 23, 1895–1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, C.H.; Minnema, B.J.; Gold, W.L. Bacterial infections complicating tongue piercing. Can. J. Infect. Dis. Med. Microbiol. 2010, 21, e70–e74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Peticolas, T.; Tilliss, T.S.; Cross-Poline, G.N. Oral and perioral piercing: A unique form of self-expression. J. Contemp. Dent. Pract. 2000, 1, 30–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hennequin-Hoenderdos, N.L.; Slot, D.E.; Van der Weijden, G.A. Complications of oral and peri-oral piercings: A summary of case reports. Int. J. Dent. Hyg. 2011, 9, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziebolz, D.; Hildebrand, A.; Proff, P.; Rinke, S.; Hornecker, E.; Mausberg, R.F. Long-term effects of tongue piercing--a case control study. Clin. Oral Investig. 2012, 16, 231–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Friedel, J.M.; Stehlik, J.; Desai, M.; Granato, J.E. Infective endocarditis after oral body piercing. Cardiol. Rev. 2003, 11, 252–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lick, S.D.; Edozie, S.N.; Woodside, K.J.; Conti, V.R. Streptococcus viridans endocarditis from tongue piercing. J. Emerg. Med. 2005, 29, 57–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Millar, B.C.; Moore, J.E. Antibiotic prophylaxis, body piercing and infective endocarditis. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2004, 53, 123–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Handrick, W.; Nenoff, P.; Müller, H.; Knöfler, W. Infections caused by piercing and tattoos—A review. Wien. Med. Wochenschr. 2003, 153, 194–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng He, R.; Nobel, T.; Greenstein, A.J. A case report of foreign body appendicitis caused by tongue piercing ingestion. Int. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2021, 81, 105808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hadi, H.I.; Quah, H.M.; Maw, A. A missing tongue stud: An unusual appendicular foreign body. Int. Surg. 2006, 91, 87–89. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Elmansi Abdalla, H.E.; Nour, H.M.; Qasim, M.; Magsi, A.M.; Sajid, M.S. Appendiceal Foreign Bodies in Adults: A Systematic Review of Case Reports. Cureus 2023, 15, e40133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Velitchkov, N.G.; Grigorov, G.I.; Losanoff, J.E.; Kjossev, K.T. Ingested foreign bodies of the gastrointestinal tract: Retrospective analysis of 542 cases. World J. Surg. 1996, 20, 1001–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicolodi, G.C.; Trippia, C.R.; Caboclo, M.F.; de Castro, F.G.; Miller, W.P.; de Lima, R.R.; Tazima, L.; Geraldo, J. Intestinal perforation by an ingested foreign body. Radiol. Bras. 2016, 49, 295–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

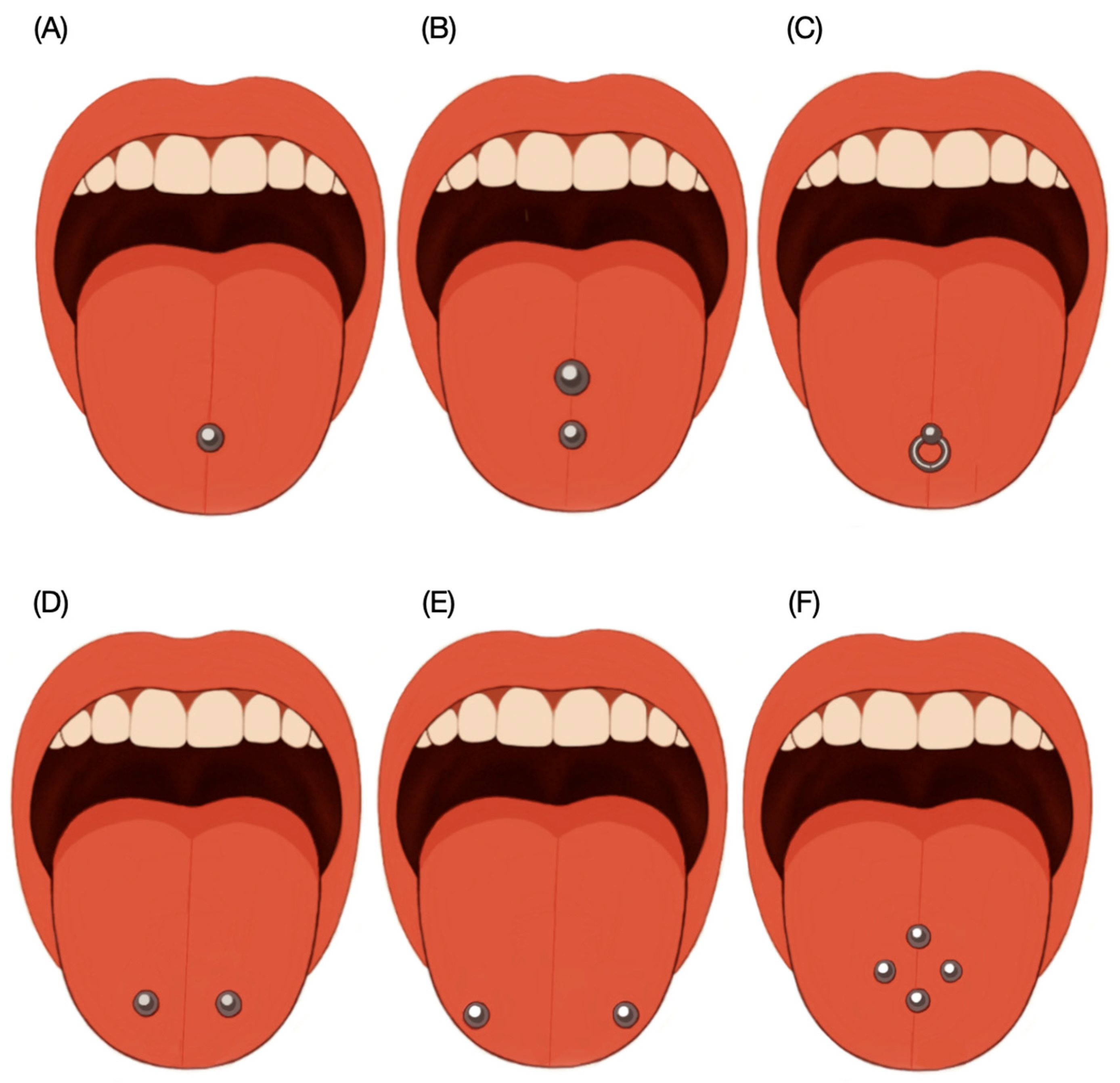

| Areas Intra-Orally | Negative Effects |

|---|---|

| Midline of the tongue | Tooth damage |

| Tip of the tongue | Gingival inflammation |

| Lower LIP | Lip inflammation |

| Cheek intra and extra-orally | Cheek inflammation |

| Lingual frenulum | |

| Maxillary frenulum | |

| Uvula |

| Criterion | Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Time period | Publications available between January 1990 and March 2025 | All publications published before January 1990 |

| Language | English | Non-English |

| Type of articles | All research types including primary research (e.g., case studies, in vitro studies, in vivo studies and reviews). Full text available. | Letters, books, book chapters, case reports lacking details on the effect of piercing. No full text not available |

| Authors/Year | Methods/Clinical Report | Results |

|---|---|---|

| Farah et al. (1998) [23] | A 25-year-old Caucasian female sought a dental consultation about getting a tongue piercing. The practitioner advised against it, explaining the potential complications. Despite this, the patient proceeded with the piercing. One week later, she returned with tongue swelling and reported difficulty speaking and chewing. She was prescribed an analgesic mouthwash and oral pain medication. | Dentists should also be able to provide consultation to patients contemplating oral piercing. While many oral piercings probably resolve uneventfully, the wide range of possible adverse outcomes associated with the procedure make it difficult to condone. |

| Brennan et al. (2006) [24] | An 18-year-old Caucasian female patient presented to the dental emergency department complaining of generalized sensitivity to cold drinks and when breathing. Clinical examination revealed dentin fracture on the palatal aspects of 15 and 24 and lingual of 34 and 36. Patient received a tongue piercing (18 mm barbell shaped). Tooth lesions were restored with resin composite. | With the growing popularity of oral piercing, patients will need to be more informed of potential complications associated with this procedure. Clinicians need to be aware of the potential etiology of dental fractures, secondary to the placement of intraoral jewelry. |

| Shinohara et al. (2007) [25] | A 16-year-old white male presented to the emergency department with healed mucosa over a tongue piercing placed four months earlier. One month after the piercing, he noticed the sphere had penetrated the central surface of his tongue. Clinical examination revealed a firm, 5 mm mass embedded in the midline. Under local anesthesia, the piercing was surgically exposed, removed, and the site was sutured. | This case reports an oral piercing with part of the hardware embedded beneath the ventral tongue mucosa, likely caused by the patient’s habit of biting and pulling on the dorsal ball before healing. The issue was resolved through surgical removal, and the patient chose not to replace the piercing. |

| Zadik et al. (2007) [26] | An 18.5-year-old female presented to the dental emergency service with mobility of her lower front teeth. Clinical exam revealed a 2.5 cm metal/plastic tongue piercing on the mid-dorsum, with a bent metal bar and calculus around the plastic sphere near the floor of the mouth. The patient had received the piercing 4.5 years earlier. Lingual gingival recession, 7 mm attachment loss, 4 mm probing depth, and type II mobility were noted in the mandibular incisors. Although informed of the damage caused by the piercing, the patient refused removal and opted to replace it with a shorter one. | Dentists should carefully exam the oral tissue of patients with oral piercing for early diagnosis of these complications. Dental surgeons have the responsibility to educate their patients about these conditions and to recommend appropriate treatment to them. |

| Berenguer et al. (2006) [27] | A 28-year-old woman presented to the department of periodontology with the chief complaint of “loose hurting teeth” in the lower anterior area. The patient had worn 2 lingual hoops and a mandibular labrette in the form of a bar for the previous 12 years. Clinical evaluation revealed severe periodontitis in the lower anterior teeth, a very unusual condition in a healthy young adult. All the mandibular anterior teeth presented from moderate to severe mobility. Probing depths ranged from 3 to 7 mm. Patient was informed that the cause was the tongue piercing and she decided to discontinue its use. | Dentists and physicians have an ethical mandate to educate patients about potential complications resulting from intraoral jewelry use. While short-term case reports have documented numerous dental injuries related to intraoral piercing, this long-term case report illustrates the potential for such devices to result in rapid periodontal destruction, tooth loss, and eventually loss of normal function. |

| Correa et al. (2014) [28] | A 23-year-old female presented with pain in the mandibular anterior region. Her medical history was unremarkable, with no tobacco use. Intraoral examination revealed a double-ended metal tongue piercing placed 7 years prior. The piercing had caused a diastema between the mandibular central incisors, with probing depths of 6–8 mm, bleeding on probing, and grade II tooth mobility. Treatment included removal of the piercing and scaling and root planing of the affected sites. | The use of oral piercings has become a fashionable practice worldwide. The mean prevalence of oral and peri-oral piercing, in general, population is 5.2%. It is generally recommended that following healing, such ornaments should be removed daily and cleaned to avoid plaque and calculus accumulation. However, some patients rarely remove their ornaments for cleaning. |

| Bajkin et al. (2014) [29] | A 15.5-year-old female presented with pain and mild swelling near the lower central incisors. Examination revealed a midline barbell-shaped tongue piercing. Both central incisors were non-vital, mobile, and showed clinical attachment loss. Incisal chipping was noted on both maxillary and mandibular central incisors. The piercing was removed, and the patient received endodontic treatment along with bone grafting for the mandibular incisors. | Bearing in mind that oral piercing is becoming a common practice, oral health professionals should educate the patients and inform them about possible oral health complications associated with this form of body art. It is especially necessary to warn patients with oral piercings about bad habits that could lead to traumatic injuries of teeth and adjacent structures. |

| Albeshri et al. (2024) [30] | A 27-year-old Hispanic female patient to the periodontics clinic. Patient was referred from a general dentist that removed her tongue piercing after 12 months of use. Piercing created swelling and suppuration in the mandibular anterior region. Probing depths ranged from 6 to 11 mm. Treatment included full mouth debridement and splint in the lower anterior region followed by bone grafting. | Tongue piercing has negative consequences for periodontal health. Correct diagnosis and treatment planning are needed for the management of various periodontal diseases. The presented case was treated successfully via regenerative therapy with a combination of allograft and membrane. The end result was that questionable teeth were saved and restored to periodontal health. |

| Kretchmer et al. (2002) [31] | A 22-year-old-male presented to the periodontology clinic for evaluation of the mandibular anterior sextant. Periapical and clinical examination revealed localized horizontal bone loss associated with lower central incisors with 6 mm probing depths, plaque and calculus. Tx included prophylaxis, flap reflection to remove supra and subgingival calculus. Patient stopped using the piercing. | The authors of this report remain confident that with the removal of the tongue stud and the stabilization of the bony lesion, the localized inflammation will resolve, and these teeth will be maintained for a significant amount of time. |

| Shacham et al. (2003) [32] | Piercing has become so popular during the last 20 to 30 years that many physicians are now treating patients with piercings and dealing with its side effects. Authors present 3 cases that illustrate the complications of tongue piercing (i.e., infection, bleeding, and embedded ornaments). Authors describe the methods for inserting the ornaments to illustrate the possible adverse effects. | When a patient does present with an inflamed tongue caused by piercing, the physician should remove the jewelry, perform a local debridement, institute antibiotic therapy, and give the patient chlorhexidine mouthwash. The patient should be closely observed to monitor the spread of infection. The opening through the tongue will spontaneously occlude. |

| Lopez-Jornet et al. (2005) [33] | A 28-year-old male patient presented with lingual piercing. A week after the piercing placement presented with pain. Two months after the ball became partially buried within the tongue. Treatment was to surgically remove the piercing under local anesthesia. Tongue healed with no further problems. | The type of piercing generally used in the tongue consists of a stud with 2 balls that are screwed to each end. It is inserted in the central, thickest area, always avoiding the lingual frenum, as well as taking care not to damage the vascular nerves. Complications are sufficiently frequent to put into question the safety of piercing, the dangers of which can be considered. |

| Fleming et al. (2005) [34] | A 17-year-old male referred to the maxillofacial clinic. Patient had a tongue ornament placed one year previously during a period of severe psychiatric disturbances. The area became infected and healed over leaving the tongue divided at the anterior or midline. The tongue was repaired under general anesthetic as a day case. The tongue healed without complication. | Unusual malformations may be attributable to tongue piercings. These abnormalities may occasionally present when ornaments are no longer in situ. Patients contemplating tongue jewelryshould be counseled on early and late complications. Likewise, dentists must be aware of the pitfalls of orofacial jewelry. |

| Patussi et al. (2014) [35] | A 23-year-old woman was referred with a painless midline nodule on the dorsal tongue, approximately 15 mm in diameter. She had worn a tongue piercing in the same area for 3 years, removed 2 years prior. The lesion was excised, and histopathology revealed an ulcerated lesion with endothelial proliferation and edematous stroma. The patient had a good outcome with no recurrence after 12 months of follow-up. | Oral piercings can cause mechanical trauma, tooth fractures, speech issues, pain, aspiration, lip inflammation, tissue overgrowth, infections, edema, allergies, tongue lacerations, black tongue, galvanism, scarring, increased saliva, interference with X-rays, nerve damage, and paresthesia. |

| Özdemir et al. (2018) [36] | AA 16-year-old female presented with severe pain and a lesion on the underside of her tongue and floor of the mouth, two months after receiving a barbell-shaped tongue piercing. Examination revealed perforation of the mouth floor. The piercing was removed under lidocaine spray in the operating room, and the patient was prescribed chlorhexidine rinses and analgesics. One week later, the lesion had healed, and the patient reported no further symptoms. | Piercings should be performed by specialists under sterile conditions. Good oral hygiene is essential to prevent bacterial colonization and infection around the piercing site. The tongue jewelry must fit snugly to avoid excessive movement but not so tight as to cause tissue necrosis. |

| Authors/Year | Methods | Results |

|---|---|---|

| Hennequin-Hoenderdos et al. (2016) [37] | The research resulted in 1865 papers and after screening by title and abstract 33 papers were selected for full-text reading, of which 17 we excluded because did not match the eligibility criteria. Finally, 15 papers were selected and processed for data extraction. | A significant relative risk was revealed between tongue piercings and an increased incidence of enamel fissures, enamel fractures and gingival recessions (especially int he lingual region of the mandibular incisors). Both lip and tongue piercings were highly associated with gingival recession |

| Plastargias et al. (2014) [38] | The purpose of this paper is to review the potential complications caused by oral piercings as they are analyzed in the literature. This manuscript also suggests some ways of improving the oral hygiene of the people who wear piercings, and it suggests some methods of ameliorating the negative consequences of piercings. | Oral piercing is not harmless at all. In fact, the vast majority of the reviews and case reports that have been published concerning this issue have agreed that oral piercings pose both a hazardous direct and indirect risk to the soft and hard oral and perioral tissues and they may even pose life-threatening risks. |

| Theodossy et al. (2014) [39] | A review of the possible complications of tongue piercing is included in the manuscript. A variety of potential complications of oral piercing have been suggested. The most common of which are pain and swelling. Edema of the tongue is a feature of all tongue piercing, because of the vascularity of the area, and can lead to airway compromise as a direct consequence or due to aspiration of the jewelry. | Dentists should be aware of the increasing number of patients with pierced intraoral and peri-oral sites and be prepared to address dental issues, such as potential damage to the teeth and gingiva and risk of oral infection, which may arise as a result of piercing. Dentists also need to provide appropriate guidance to patients who are contemplating body piercing involving oral sites. |

| Maheu-Robert et al. (2007) [40] | It is a brief review of the current literature on potential complications and adverse consequences of tongue and lip piercings. The objective is to provide a general overview of possible problems that may be encountered by dentists. In addition, authors highlight the urgent need for dentists and doctors to inform target patients of the risks associated with oral piercings. | Tongue and lip piercings represent a significant risk for direct and indirect damage to soft and hard oral tissues. Although much less prevalent, lethal systemic infections may also occur. Considering the growing popularity of intraoral and perioral piercings, dental professionals should be aware of the potential complications associated with this practice and be able to identify those at high risk for adverse outcomes. |

| Ziebolz et al. (2009) [41] | Dental professionals are seeing an increasing number of patients with oral piercings and as a result they should be able to inform their patients about possible risks and complications associated with such piercings. | The three cases presented here demonstrate some adverse effects of tongue piercings. The most commonly described oral complication is the damage of teeth and the periodontium. Tongue piercing is a personal decision, but it is important patients are fully aware of possible oral health hazards. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rojas-Rueda, S.; Citrin, N.S.; Antal, M.A.; Garcia-Contreras, R.; Jurado, C.A.; Azpiazu-Flores, F.X. Impact of Tongue Piercings on Oral Health: A Narrative Literature Review. Clin. Pract. 2025, 15, 171. https://doi.org/10.3390/clinpract15090171

Rojas-Rueda S, Citrin NS, Antal MA, Garcia-Contreras R, Jurado CA, Azpiazu-Flores FX. Impact of Tongue Piercings on Oral Health: A Narrative Literature Review. Clinics and Practice. 2025; 15(9):171. https://doi.org/10.3390/clinpract15090171

Chicago/Turabian StyleRojas-Rueda, Silvia, Nechama S. Citrin, Mark Adam Antal, Rene Garcia-Contreras, Carlos A. Jurado, and Francisco X. Azpiazu-Flores. 2025. "Impact of Tongue Piercings on Oral Health: A Narrative Literature Review" Clinics and Practice 15, no. 9: 171. https://doi.org/10.3390/clinpract15090171

APA StyleRojas-Rueda, S., Citrin, N. S., Antal, M. A., Garcia-Contreras, R., Jurado, C. A., & Azpiazu-Flores, F. X. (2025). Impact of Tongue Piercings on Oral Health: A Narrative Literature Review. Clinics and Practice, 15(9), 171. https://doi.org/10.3390/clinpract15090171