Reframing Polypharmacy: Empowering Medical Students to Manage Medication Burden as a Chronic Condition

Abstract

1. Introduction

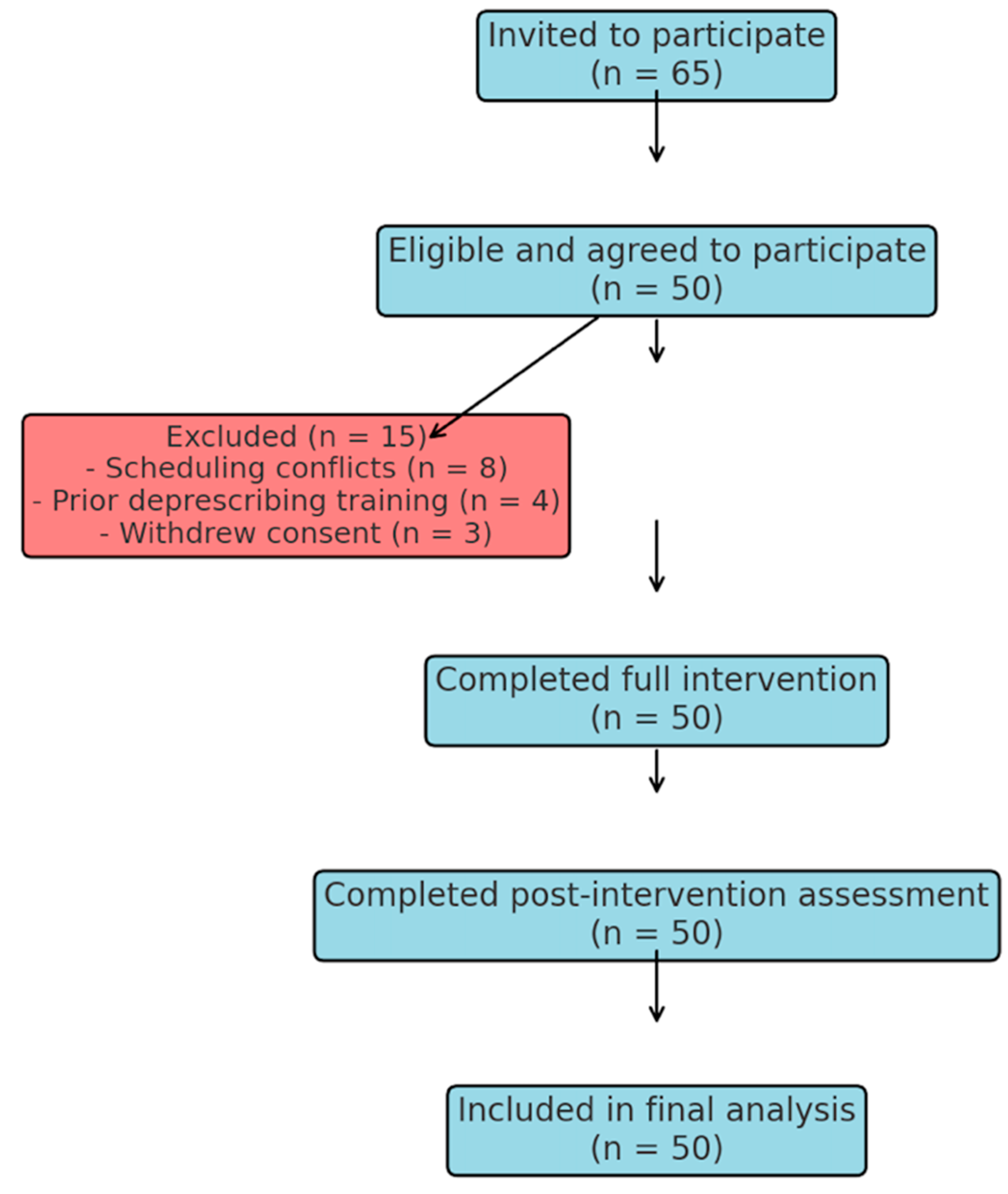

2. Participants and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Setting

2.3. Participants

2.4. Variables and Quantitative Measures

2.5. Data Sources and Measurement

2.6. Interventional Methods

2.7. Bias

2.8. Study Size

2.9. Statistical Methods

2.10. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Participants

3.2. Impact on Knowledge and Confidence

3.3. Phased Analysis of Intervention Impact

3.4. Impact of Clinical Experience on Learning Outcomes

- Baseline confidence scores:

- ○

- Students with prior geriatrics exposure: 3.1 ± 0.6

- ○

- Students without prior exposure: 2.7 ± 0.7 (p = 0.07, nonsignificant)

- Post-intervention confidence:

- ○

- With geriatrics exposure: 4.6 ± 0.3

- ○

- Without geriatrics exposure: 4.4 ± 0.4 (p = 0.04)

- Knowledge of deprescribing tools:

- ○

- With prior exposure: 3.4 ± 0.5 → 4.8 ± 0.3

- ○

- Without exposure: 2.9 ± 0.6 → 4.5 ± 0.3 (p < 0.01)

Nonsignificant Findings

- Confidence in differentiating adverse drug reactions improved from 3.5 ± 0.7 to 3.9 ± 0.6 (p = 0.08)

- Understanding of pharmacokinetic changes improved from 3.2 ± 0.6 to 3.5 ± 0.5 (p = 0.09)

3.5. Performance in Simulated Patient Interactions

3.6. Insights from Medication Review Exercises

3.7. Reflective Insights

4. Discussion

4.1. Key Results

4.2. Limitations

4.3. Interpretation

4.4. Generalisability

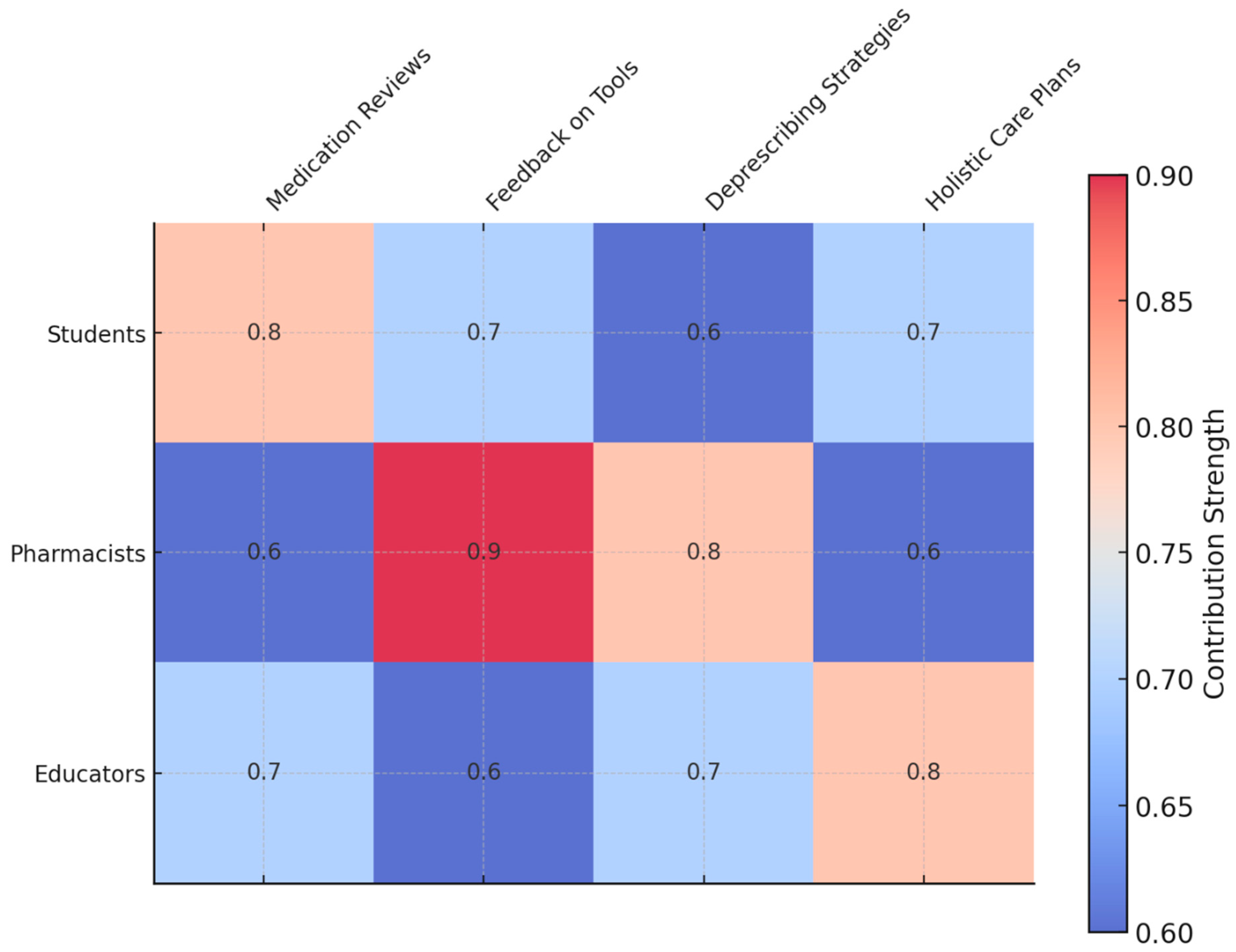

4.5. Bridging Education and Policy in Managing Polypharmacy

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Student Evaluation Form

Appendix A.1. Pre-Training Survey

| Statement | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| I feel confident identifying polypharmacy-related symptoms (e.g., fatigue, dizziness, confusion). | |||||

| I am familiar with the concept of polypharmacy as a chronic condition. | |||||

| I understand the role of prescribing cascades in medication-related problems. | |||||

| I am comfortable using tools like medication review checklists or electronic health records. | |||||

| I am aware of the importance of deprescribing as part of managing polypharmacy. | |||||

| I feel confident discussing medication-related issues with patients and caregivers. |

- What challenges do you foresee in identifying polypharmacy-related symptoms during patient interactions?

- What do you hope to learn from this training?

- How would you describe your current approach to medication review and deprescribing?

Appendix A.2. Post-Training Survey

| Statement | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| I feel confident identifying polypharmacy-related symptoms (e.g., fatigue, dizziness, confusion). | |||||

| I am familiar with the concept of polypharmacy as a chronic condition. | |||||

| I understand the role of prescribing cascades in medication-related problems. | |||||

| I am comfortable using tools like medication review checklists or electronic health records. | |||||

| I am aware of the importance of deprescribing as part of managing polypharmacy. | |||||

| I feel confident discussing medication-related issues with patients and caregivers. |

- What was the most valuable skill or insight you gained from this training?

- How has your approach to medication review and deprescribing changed after this experience?

- What challenges do you still anticipate in managing polypharmacy, and how might you address them?

- Describe a scenario where you identified polypharmacy as a primary cause of a patient’s symptoms. How did you address this issue?

- Reflect on a situation where you struggled to propose a deprescribing strategy. What made it challenging, and how did you overcome it?

- How has this training influenced your approach to patient-centred care and medication management?

- What role did collaboration with pharmacists or other team members play in shaping your understanding of polypharmacy?

- What strategies will you use to integrate polypharmacy management into your future clinical practice?

Appendix B. Standardised Patient Feedback Form

| Statement | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| The student demonstrated an understanding of how polypharmacy impacts my health and quality of life. | |||||

| The student communicated clearly and empathetically about medication-related concerns. | |||||

| The student identified potential issues with my medication regimen effectively. | |||||

| The student included me in the decision-making process regarding medication adjustments. | |||||

| The student’s approach made me feel heard and respected during the interaction. |

- What did the student do well during this interaction?

- Was there anything the student could have done better? If so, please explain.

- How did the student’s attention to medication-related issues impact your perception of the interaction?

Appendix C. Sample Intervention Material

- Phase 1: Interactive Workshops

- Phase 2: Practical Application

- Phase 3: Reflection and Evaluation

References

- Toh, J.J.Y.; Zhang, H.; Soh, Y.Y.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, X.V. Prevalence and health outcomes of polypharmacy and hyperpolypharmacy in older adults with frailty: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res. Rev. 2023, 83, 101811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, A.; Veríssimo, M.; Ribeiro, O. Deprescribing in Older Adults: Attitudes, Awareness, Training, and Clinical Practice Among Portuguese Physicians. Acta Med. Port. 2024, 37, 684–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doherty, A.S.; Boland, F.; Moriarty, F.; Fahey, T.; Wallace, E. Adverse drug reactions and associated patient characteristics in older community-dwelling adults: A 6-year prospective cohort study. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2023, 73, e211–e219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerjes, W.; Harding, D. Confronting polypharmacy and social isolation in elderly care: A general practitioner’s perspective on holistic primary care. Front. Aging 2024, 5, 1384835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.T.; Chan, H.K.; Liew, E.J.Y.; Abu Hassan, M.R.; Lee, J.C.Y.; Cheah, W.K.; Lim, X.J.; Rajan, P.; Teoh, S.L.; Lee, S.W.H. Factors influencing healthcare providers’ behaviours in deprescribing: A cross-sectional study. J. Pharm. Policy Pr. 2024, 17, 2399727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Baena, J.M.; Moreno-Juste, A.; Poblador-Plou, B.; Castillo-Jimena, M.; Calderón-Larrañaga, A.; Lozano-Hernández, C.; Gimeno-Miguel, A.; Gimeno-Feliú, L.A.; Multipap Group. Influence of social determinants of health on quality of life in patients with multimorbidity and polypharmacy. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0297702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerjes, W. Rethinking polypharmacy: Empowering junior doctors to tackle a chronic condition in modern practice. Postgrad. Med. J. 2025, 101, 667–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canio, W.C. Polypharmacy in Older Adults. Clin. Geriatr. Med. 2022, 38, 621–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huffmyer, M.J.; Keck, J.W.; Harrington, N.G.; Freeman, P.R.; Westling, M.; Lukacena, K.M.; Moga, D.C. Primary care clinician and community pharmacist perceptions of deprescribing. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2021, 69, 1686–1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reeve, E.; Gnjidic, D.; Long, J.; Hilmer, S. A systematic review of the emerging definition of ‘deprescribing’ with network analysis: Implications for future research and clinical practice. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2015, 80, 1254–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jyrkkä, J.; Enlund, H.; Korhonen, M.J.; Sulkava, R.; Hartikainen, S. Patterns of drug use and factors associated with polypharmacy and excessive polypharmacy in elderly persons: Results of the Kuopio 75+ study: A cross-sectional analysis. Drugs Aging 2009, 26, 493–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donnell, L.K.; Ibrahim, K. Polypharmacy and deprescribing: Challenging the old and embracing the new. BMC Geriatr. 2022, 22, 734. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Brooks, C.F.; Argyropoulos, A.; Matheson-Monnet, C.B.; Kryl, D. Evaluating the impact of a polypharmacy Action Learning Sets tool on healthcare practitioners’ confidence, perceptions and experiences of stopping inappropriate medicines. BMC Med. Educ. 2022, 22, 499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, D.; Cernasev, A.; Barenie, R.E.; Springer, S.P.; Axon, D.R. Teaching Deprescribing and Combating Polypharmacy in the Pharmacy Curriculum: Educational Recommendations from Thematic Analysis of Focus Groups. Clin. Pract. 2023, 13, 442–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaszczyk, A.T.; Mahan, R.J.; McCarrell, J.; Sleeper, R.B. Using a Polypharmacy Simulation Exercise to Increase Empathy in Pharmacy Students. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2018, 82, 6238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, J. Likert Scale. In Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research; Michalos, A.C., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 3620–3621. [Google Scholar]

- Olesen, A.E.; Vaever, T.J.; Simonsen, M.; Simonsen, P.G.; Høj, K. Deprescribing in primary care without deterioration of health-related outcomes: A real-life, quality improvement project. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2024, 134, 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeve, E.; Shakib, S.; Hendrix, I.; Roberts, M.S.; Wiese, M.D. Review of deprescribing processes and development of an evidence-based, patient-centred deprescribing process. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2014, 78, 738–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clyne, B.; Cooper, J.A.; Boland, F.; Hughes, C.M.; Fahey, T.; Smith, S.M. Beliefs about prescribed medication among older patients with polypharmacy: A mixed methods study in primary care. Br. J. Gen. Pr. 2017, 67, e507–e518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isenor, J.E.; Bai, I.; Cormier, R.; Helwig, M.; Reeve, E.; Whelan, A.M.; Burgess, S.; Martin-Misener, R.; Kennie-Kaulbach, N. Deprescribing interventions in primary health care mapped to the Behaviour Change Wheel: A scoping review. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2021, 17, 1229–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, R.E.; Thomas, B.C. A Systematic Review of Studies of the STOPP/START 2015 and American Geriatric Society Beers 2015 Criteria in Patients ≥ 65 Years. Curr. Aging Sci. 2019, 12, 121–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Te Winkel, M.T.; Damoiseaux-Volman, B.A.; Abu-Hanna, A.; Lissenberg-Witte, B.I.; van Marum, R.J.; Schers, H.J.; Slottje, P.; Uijen, A.A.; Bont, J.; Maarsingh, O.R. Personal Continuity and Appropriate Prescribing in Primary Care. Ann. Fam. Med. 2023, 21, 305–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doherty, A.J.; Boland, P.; Reed, J.; Clegg, A.J.; Stephani, A.M.; Williams, N.H.; Shaw, B.; Hedgecoe, L.; Hill, R.; Walker, L. Barriers and facilitators to deprescribing in primary care: A systematic review. BJGP Open 2020, 4, bjgpopen20X101096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerlach, N.; Michiels-Corsten, M.; Viniol, A.; Schleef, T.; Junius-Walker, U.; Krause, O.; Donner-Banzhoff, N. Professional roles of general practitioners, community pharmacists and specialist providers in collaborative medication deprescribing—A qualitative study. BMC Fam Pr. 2020, 21, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillespie, R.; Mullan, J.; Harrison, L. Factors which influence the deprescribing decisions of community-living older adults and GPs in Australia. Health Soc. Care Community 2022, 30, e6206–e6216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, P.; Tannenbaum, C. A realist evaluation of patients’ decisions to deprescribe in the EMPOWER trial. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e015959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmes, H.M.; Todd, A. The Role of Patient Preferences in Deprescribing. Clin. Geriatr. Med. 2017, 33, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weir, K.; Nickel, B.; Naganathan, V.; Bonner, C.; McCaffery, K.; Carter, S.M.; McLachlan, A.; Jansen, J. Decision-Making Preferences and Deprescribing: Perspectives of Older Adults and Companions About Their Medicines. J. Gerontol. Ser. B 2018, 73, e98–e107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nixon, M.; Kousgaard, M.B. Organising medication discontinuation: A qualitative study exploring the views of general practitioners toward discontinuing statins. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2016, 16, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, M.I.; Young, A.; Maher, R.; Rodriguez, K.L.; Appelt, C.J.; Perera, S.; Hajjar, E.R.; Hanlon, J.T. Polypharmacy and health beliefs in older outpatients. Am. J. Geriatr. Pharmacother. 2007, 5, 317–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Phase | Key Activities | Learning Objectives | Outcomes Measured |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phase 1: Interactive workshops |

|

|

|

| Phase 2: Practical application |

|

|

|

| Phase 3: Reflection and evaluation |

|

|

|

| Metric | Pre-Training Score (Mean ± SD)/% | Post-Training Score (Mean ± SD)/% | Change | Key Observations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Confidence in identifying polypharmacy-related symptoms | 4.7 ± 0.7 | 4.5 ± 0.4 | +1.6 points (p < 0.01) | Students demonstrated significant improvement in recognising symptoms like fatigue, dizziness, and confusion as potential drug effects. |

| Knowledge of diagnostic tools and strategies | 3.1 ± 0.6 | 4.7 ± 0.3 | +1.6 points (p < 0.01) | Marked increase in familiarity with tools for identifying prescribing cascades and drug–drug interactions. |

| Awareness of multidisciplinary collaboration | 3.2 ± 0.7 | 4.6 ± 0.4 | +1.4 points (p < 0.01) | Students gained a deeper understanding of the importance of pharmacist collaboration in managing polypharmacy. |

| Confidence in proposing deprescribing strategies | e.g., 3.0 ± 0.6 | 4.3 ± 0.5 | +1.3 points (p < 0.01) | Marked improvement in confidence and ability to propose safe medication reduction strategies |

| Standardised patient satisfaction ratings → Communication skills | 3.5 ± 0.8 | 4.8 ± 0.4 | +1.3 points (p < 0.01) | Patients reported greater satisfaction with students’ ability to communicate effectively and address medication concerns. |

| Identification of drug–drug interactions per patient record | 2.4 ± 0.6 | 4.7 ± 0.5 | +2.3 points (p < 0.01) | Students significantly improved in identifying drug–drug interactions during medication review exercises. |

| Ability to propose deprescribing strategies (%) | 34% | 78% | +44% | Significant improvement in students’ ability to identify and recommend discontinuing unnecessary medications. |

| Students who recognised polypharmacy as a primary diagnostic consideration (%) | 32% | 86% | +54% | Increased awareness of polypharmacy as a central factor in patient presentations. |

| Students confident in engaging patients in medication discussions (%) | 40% | 84% | +44% | Enhanced ability to involve patients in shared decision-making around deprescribing. |

| Students confident in using diagnostic tools for drug–drug interactions (%) | 84% | 94% | +10% | Improved ability to apply tools for deprescribing strategies. |

| Students confident in multidisciplinary collaboration (%) | 32% | 86% | +54% | Stronger recognition of team-based approaches in polypharmacy. |

| Recognition of polypharmacy-related symptoms (%) | 38% | 88% | +50% | Greater awareness of symptoms attributable to medication effects. |

| Domain | Post-Workshop (Mean ± SD) | Post-Practical (Mean ± SD) | Post-Reflection (Mean ± SD) | t-Value (Final vs. Baseline) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Confidence in identifying symptoms | 3.8 ± 0.5 | 4.2 ± 0.4 | 4.5 ± 0.4 | 9.2 | Post-workshop < 0.05; Post-practical and Post-reflection <0.01 |

| Knowledge of diagnostic tools | 3.9 ± 0.5 | 4.4 ± 0.3 | 4.7 ± 0.3 | 11.8 | <0.01 |

| Multidisciplinary collaboration | 3.7 ± 0.5 | 4.2 ± 0.4 | 4.6 ± 0.4 | 10.3 | <0.01 |

| Confidence in proposing deprescribing | 3.6 ± 0.6 | 4.0 ± 0.5 | 4.3 ± 0.5 | 8.1 | <0.01 |

| Communication skills | 3.9 ± 0.6 | 4.3 ± 0.5 | 4.8 ± 0.4 | 8.6 | <0.01 |

| Identification of drug–drug interactions | 3.5 ± 0.6 | 4.2 ± 0.5 | 4.7 ± 0.5 | 10.5 | <0.01 |

| Outcome | Post-Workshop (%) | Post-Practical (%) | Post-Reflection (%) | McNemar p-Value (Final vs. Baseline) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ability to propose deprescribing | 58 | 74 | 90 | <0.01 |

| Recognition of polypharmacy as a diagnostic issue | 64 | 79 | 88 | <0.01 |

| Confidence in engaging patients | 60 | 76 | 84 | <0.01 |

| Confidence in using diagnostic tools | 88 | 92 | 94 | <0.01 |

| Confidence in multidisciplinary collaboration | 72 | 81 | 86 | <0.01 |

| Recognition of polypharmacy-related symptoms | 64 | 79 | 88 | <0.01 |

| Theme | Description | Illustrative Quotes | Key Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recognition of Polypharmacy-Related Symptoms | Students increasingly identified drug-induced symptoms as distinct from disease progression. | “I never realised how much medications could mimic symptoms of disease. This training made me rethink my approach.” | Reinforces the need for polypharmacy to be a routine part of differential diagnosis in clinical practice. |

| Proactive Deprescribing | Students proposed deprescribing strategies to alleviate medication burden and improve patient outcomes. | “Reducing unnecessary medications felt like I was giving the patient their life back.” | Highlights the value of deprescribing as a core skill for improving patient quality of life. |

| Collaborative Problem-Solving | Students emphasised the importance of working with pharmacists and other team members in managing polypharmacy. | “The pharmacist provided insights I hadn’t considered, which made our plan more comprehensive.” | Demonstrates the value of interprofessional collaboration in addressing complex medication regimens. |

| Enhanced Communication Skills | Standardised patients noted improvements in students’ ability to explain medication-related issues clearly and empathetically. | “The student explained why reducing my medications could help and made me feel part of the decision.” | Empathy and clear communication are essential for patient-centred polypharmacy management. |

| Diagnostic Growth | Students developed a mindset that positioned polypharmacy as a primary consideration in patient assessments. | “Polypharmacy is no longer just a side note—it’s a key part of my diagnostic process now.” | Encourages future clinicians to routinely include polypharmacy in their diagnostic frameworks. |

| Realising Systemic Impacts | Students recognised how systemic factors, such as prescribing cascades, contribute to polypharmacy challenges. | “It’s clear that many issues stem from a fragmented healthcare approach to medications.” | Promotes a systems-based perspective to address polypharmacy at both individual and organisational levels. |

| Reflective and Lifelong Learning | Students acknowledged the importance of continued learning and reflection in managing polypharmacy effectively. | “This experience showed me that managing medications is an ongoing process, not a one-time decision.” | Encourages a commitment to lifelong learning in managing evolving medication challenges. |

| Clinical Scenario (Patient and Comorbidities) | Medication Regimen | Identified Polypharmacy Issue | Student Interpretation and Response | Deprescribing Outcome and Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mrs. J, 82 years, dementia, hypertension, chronic pain | Donepezil, Ramipril, Amitriptyline, Diclofenac, Omeprazole | Cognitive impairment and frequent falls likely exacerbated by anticholinergic effects (Amitriptyline) and renal impact of NSAIDs (Diclofenac) | Students identified medications contributing to falls and confusion, recognising potential drug-induced cognitive impairment and risk of gastrointestinal and renal complications. | Discontinued Amitriptyline due to anticholinergic side effects and replaced Diclofenac with safer analgesics (e.g., paracetamol), significantly reducing fall risk. |

| Mr. A, 78 years, COPD, osteoporosis, type 2 diabetes | Salbutamol, Tiotropium, Alendronic Acid, Prednisolone, Metformin, Ibuprofen | Unnecessary long-term corticosteroid therapy causing hyperglycaemia and osteoporosis risk; Ibuprofen exacerbating gastrointestinal symptoms | Students correctly interpreted prolonged prednisolone as problematic for glycaemic control and bone density. Proposed safe corticosteroid tapering and recognised Ibuprofen as contraindicated due to gastrointestinal risks. | Initiated structured corticosteroid tapering; Ibuprofen replaced by topical analgesics to manage osteoarthritis pain safely. |

| Mrs. P, 84 years, atrial fibrillation, insomnia, anxiety | Warfarin, Atenolol, Diazepam, Zolpidem, Simvastatin | Sedative-hypnotic medications increasing risk of confusion, falls, and anticoagulation complications | Students identified diazepam and zolpidem contributing significantly to confusion and fall risk, proposing alternative non-pharmacological strategies for anxiety and sleep management. | Diazepam and Zolpidem gradually deprescribed; implemented behavioural interventions, reducing fall and confusion episodes. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Conte, A.; Sedghi, A.; Majeed, A.; Jerjes, W. Reframing Polypharmacy: Empowering Medical Students to Manage Medication Burden as a Chronic Condition. Clin. Pract. 2025, 15, 142. https://doi.org/10.3390/clinpract15080142

Conte A, Sedghi A, Majeed A, Jerjes W. Reframing Polypharmacy: Empowering Medical Students to Manage Medication Burden as a Chronic Condition. Clinics and Practice. 2025; 15(8):142. https://doi.org/10.3390/clinpract15080142

Chicago/Turabian StyleConte, Andreas, Anita Sedghi, Azeem Majeed, and Waseem Jerjes. 2025. "Reframing Polypharmacy: Empowering Medical Students to Manage Medication Burden as a Chronic Condition" Clinics and Practice 15, no. 8: 142. https://doi.org/10.3390/clinpract15080142

APA StyleConte, A., Sedghi, A., Majeed, A., & Jerjes, W. (2025). Reframing Polypharmacy: Empowering Medical Students to Manage Medication Burden as a Chronic Condition. Clinics and Practice, 15(8), 142. https://doi.org/10.3390/clinpract15080142