The Impact of the Quality of Care for Adults with Acute Asthma in the Emergency Department of a Tertiary Hospital: A 1-Year Follow-Up Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Patients

2.2. Study Outcomes

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Patients

3.2. The Management of Exacerbations at the ED and Discharge Reports

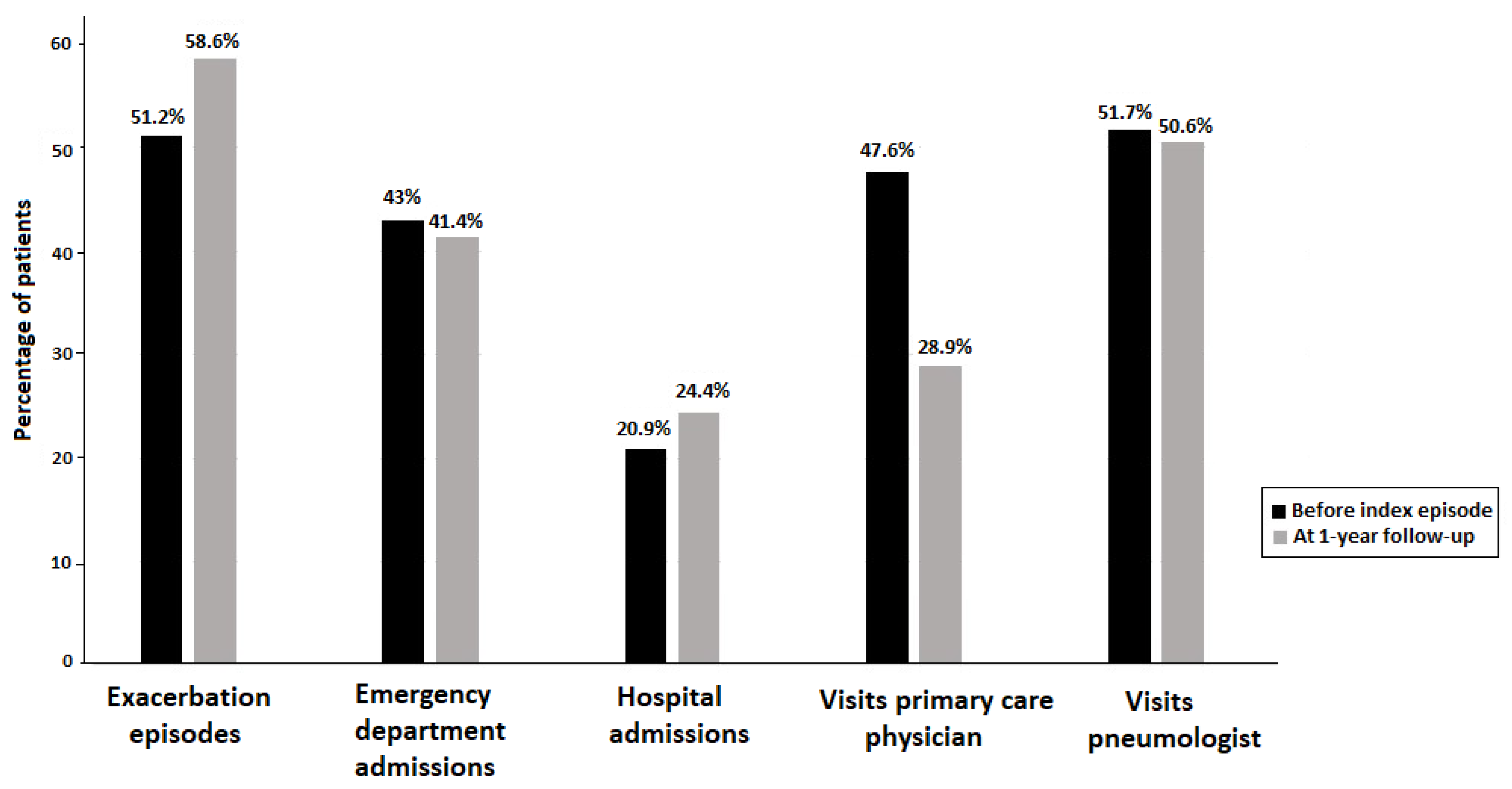

3.3. Follow-Up at 1 Year

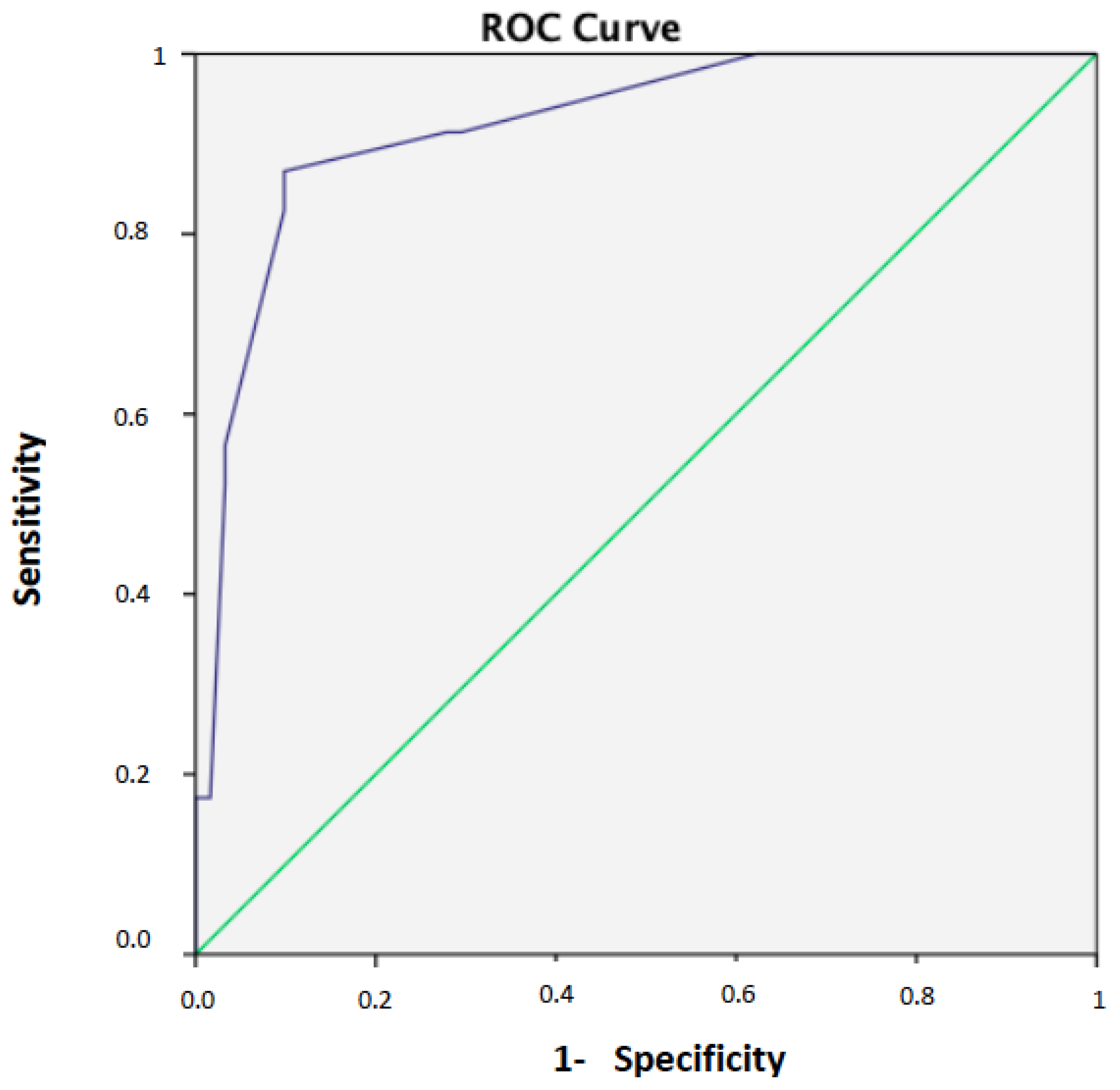

3.4. Risk Factors for Poor Asthma Control

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ED | Emergency department |

| ICS | Inhaled corticosteroids |

| LABA | Long-acting β2-agonists |

| SABA | Short-acting β2-agonists |

| COPD | Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

| GINA | Global Initiative for Asthma |

| CEIC | Ethics Committee for Clinical Research |

| GEMA | Guideline on the Management of Asthma |

| ICD | International Classification of Diseases |

| ACT | Asthma Control Test |

| TAI | Test of Adherence to Inhalers |

| SaO2 | Arterial oxygen saturation |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| OR | Odds ratio |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| ROC | Receiver operating characteristic curve |

| AUC | Area under the ROC curve |

| SPSS | Statistical Package for the Social Sciences |

| LAMA | Long-acting muscarinic antagonist |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| GERD | Gastroesophageal reflux disease |

| PEF | Peak expiratory flow |

References

- Global Initiative for Asthma. 2023 GINA Report, Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention. Available online: https://ginasthma.org/2023-gina-main-report/ (accessed on 23 January 2025).

- Plaza Moral, V.; Alobid, I.; Álvarez Rodríguez, C.; Blanco Aparicio, M.; Ferreira, J.; García, G.; Gómez-Outes, A.; Garín Escrivá, N.; Gómez Ruiz, F.; Hidalgo Requena, A.; et al. GEMA 5.3. Spanish Guideline on the Management of Asthma. Open Respir. Arch. 2023, 5, 100277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dougherty, R.H.; Fahy, J.V. Acute exacerbations of asthma: Epidemiology, biology and the exacerbation-prone phenotype. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2009, 39, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caballero-Segura, F.J.; Lopez-de-Andres, A.; Jimenez-Garcia, R.; de Miguel-Yanes, J.M.; Hernández-Barrera, V.; Carabantes-Alarcon, D.; Zamorano-Leon, J.J.; de Miguel-Díez, J. Trends in asthma hospitalizations among adults in Spain: Analysis of hospital discharge data from 2011 to 2020. Respir. Med. 2022, 204, 107009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Byrne, P.M.; Pedersen, S.; Lamm, C.J.; Tan, W.C.; Busse, W.W.; START Investigators Group. Severe exacerbations and decline in lung function in asthma. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2009, 179, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, D.J.; Sykes, A.; Mallia, P.; Johnston, S.L. Asthma exacerbations: Origin, effect, and prevention. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2011, 128, 1165–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rueegg, M.; Busch, J.M.; van Iperen, P.; Leuppi, J.D.; Bingisser, R. Characteristics of asthma exacerbations in emergency care in Switzerland-demographics, treatment, and burden of disease in patients with asthma exacerbations presenting to an emergency department in Switzerland (CARE-S). J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 2857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schnyder, D.; Lüthi-Corridori, G.; Leuppi-Taegtmeyer, A.B.; Boesing, M.; Geigy, N.; Leuppi, J.D. Audit of asthma exacerbation management in a Swiss general hospital. Respiration 2023, 102, 12–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tapp, S.; Lasserson, T.J.; Rowe, B.H. Education interventions for adults who attend the emergency room for acute asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007, 2007, CD003000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasegawa, K.; Chiba, T.; Hagiwara, Y.; Watase, H.; Tsugawa, Y.; Brown, D.F.; Camargo, C.A., Jr.; Japanese Emergency Medicine Network Investigators. Quality of care for acute asthma in emergency departments in Japan: A multicenter observational study. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2013, 1, 509–515.e1–e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pola-Bibian, B.; Dominguez-Ortega, J.; Vilà-Nadal, G.; Entrala, A.; González-Cavero, L.; Barranco, P.; Cancelliere, N.; Díaz-Almirón, M.; Quirce, S. Asthma exacerbations in a tertiary hospital: Clinical features, triggers, and risk factors for hospitalization. J. Investig. Allergol. Clin. Immunol. 2024, 27, 238–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Domínguez-Ortega, J.; Luna-Porta, J.A.; Olaguibel, J.M.; Barranco, P.; Arismendi, E.; Barroso, B.; Betancor, D.; Bobolea, I.; Caballero, M.L.; Cárdaba, B.; et al. Exacerbations among patients with asthma are largely dependent on the presence of multimorbidity. J. Investig. Allergol. Clin. Immunol. 2023, 33, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piñera Salmerón, P.; Delgado Romero, J.; Domínguez Ortega, J.; Labrador Horrillo, M.; Álvarez Gutiérrez, F.J.; Martínez Moragón, E.; Moral, V.P.; Rodríguez, C.Á.; Franco, J.M. Documento de consenso para el manejo del paciente asmático en urgencias. Emergencias 2018, 30, 268–278. [Google Scholar]

- Forward, C.; O’Loghlin, R.; Mulryan, H.; Langan, D.; Harrison, M.; Rutherford, R.; Cusack, R. Asthma patients discharged from the emergency department in Ireland: An unmet need? Eur. Respir. J. 2022, 60 (Suppl. S66), 1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awli, Y.F.; Addis, G. An audit of the British Thoracic Society asthma discharge care bundle in a teaching hospital. Br. J. Nurs. 2021, 30, 772–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, C.E.; Zhang, H.P.; Lv, Y.; Liang, R.; Jiang, Y.Q.; Powell, H.; Fu, J.J.; Wang, L.; Gibson, P.G.; Wang, G. The Asthma Control Test and Asthma Control Questionnaire for assessing asthma control: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2013, 131, 695–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plaza, V.; Fernández-Rodríguez, C.; Melero, C.; Cosío, B.G.; Entrenas, L.M.; de Llano, L.P.; Gutiérrez-Pereyra, F.; Tarragona, E.; Palomino, R.; López-Viña, A.; et al. Validation of the ‘Test of the Adherence to Inhalers’ (TAI) for asthma and COPD patients. J. Aerosol Med. Pulm. Drug Deliv. 2016, 29, 142–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, K.R.; Meltzer, E.O.; Blaiss, M.S.; Nathan, R.A.; Stoloff, S.W.; Doherty, D.E. Asthma management and control in the United States: Results of the 2009 Asthma Insight and Management survey. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2012, 33, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsuyuki, R.T.; Sin, D.D.; Sharpe, H.M.; Cowie, R.L.; Nilsson, C.; Man, S.F.; Alberta Strategy to Help Manage Asthma (ASTHMA) Investigators. Management of asthma among community-based primary care physicians. J. Asthma 2005, 42, 163–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa-Roel, C.; Borgundvaag, B.; Majumdar, S.R.; Emond, M.; Campbell, S.; Sivilotti, M.; Abu-Laban, R.B.; Stiell, I.G.; Aaron, S.D.; Senthilselvan, A.; et al. Reasons and outcomes for patients receiving ICS/LABA agents prior to, and one month after, emergency department presentations for acute asthma. J. Asthma 2019, 56, 985–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- To, T.; Cicutto, L.; Degani, N.; McLimont, S.; Beyene, J. Can a community evidence-based asthma care program improve clinical outcomes?: A longitudinal study. Med. Care 2008, 46, 1257–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, M.J.; Tsiligianni, I.; Kocks, J.W.H.; Cave, A.; Chunhua, C.; Sousa, J.C.; Román-Rodríguez, M.; Thomas, M.; Kardos, P.; Stonham, C.; et al. Improving primary care management of asthma: Do we know what really works? NPJ Prim. Care Respir. Med. 2020, 30, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Backer, V.; Harving, H.; Søes-Petersen, U.; Ulrik, C.S.; Plaschke, P.; Lange, P. Treatment and evaluation of patients with acute exacerbation of asthma before and during a visit to the ER in Denmark. Clin. Respir. J. 2008, 2, 54–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, B.H.; Symonds, P.; Mankragod, R.H.; Morris, K. A national audit of the secondary care of “acute” asthma in Wales—February 2006. Respir. Med. 2009, 103, 827–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Royal College of Emergency Medicine. Moderate & Acute Severe Asthma. Clinical Audit 2016/17. National Report. Available online: https://rcem.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/Moderate_and_Acute_Severe_Asthma_Clinical_Audit_2016_17.pdf (accessed on 28 January 2025).

- Villa-Roel, C.; Nikel, T.; Ospina, M.; Voaklander, B.; Campbell, S.; Rowe, B.H. Effectiveness of educational interventions to increase primary care follow-up for adults seen in the emergency department for acute asthma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2016, 23, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Roos, E.W.; Lahousse, L.; Verhamme, K.M.C.; Braunstahl, G.J.; In ‘t Veen, J.C.C.M.; Stricker, B.H.; Brusselle, G.G.O. Incidence and predictors of asthma exacerbations in middle-aged and older adults: The Rotterdam Study. ERJ Open Res. 2021, 7, 00126-2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallis, C.; Calvo, R.A.; Schuller, B.; Quint, J.K. Development of an asthma exacerbation risk prediction model for conversational use by adults in England. Pragmat. Obs. Res. 2023, 14, 111–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwaru, B.I.; Ekström, M.; Hasvold, P.; Wiklund, F.; Telg, G.; Janson, C. Overuse of short-acting β2-agonists in asthma is associated with increased risk of exacerbation and mortality: A nationwide cohort study of the global SABINA programme. Eur. Respir. J. 2020, 55, 1901872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, L.B.; Usery, J.B.; Finch, C.K.; Wallace, J.L.; Deaton, P.R.; Self, T.H. Inadequate documentation of asthma management in hospitalized adult patients. South. Med. J. 2009, 102, 510–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study Variables | Patients (%) | Mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Female patients, n = 87 | 70 (80.5) | |

| Age, years, n = 87 | 51.2 (23) | |

| Smoking status, n = 84 | ||

| Active smoker | 15 (17.9) | |

| Ex-smoker | 11 (13.1) | |

| Never smoker | 58 (69.0) | |

| Comorbidity | ||

| Obesity, body mass index (BMI) > 30 kg/m2, n = 83 | 31 (37.3) | |

| Hypertension, n = 87 | 28 (32.2) | |

| Diabetes mellitus, n = 87 | 14 (16.1) | |

| Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), n = 82 | 15 (18.3) | |

| Nasal polyposis, n = 72 | 7 (9.7) | |

| Anxiety, n = 85 | 29 (34.1) | |

| Depression, n = 84 | 20 (23.8) | |

| Prick test, n = 87 | ||

| Positive | 30 (34.5) | |

| Negative | 7 (8.0) | |

| Unavailable data | 50 (57.5) | |

| Severity of asthma, n = 54 | ||

| Mild | 15 (27.8) | |

| Moderate | 12 (22.2) | |

| Severe | 27 (50.0) | |

| Previous treatment for asthma | ||

| Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS), n = 85 | 56 (65.9) | |

| ICS, µg budesonide equivalent | 471.6 (315) | |

| ICS only, n = 85 | 6 (7.1) | |

| ICS-LABA, n = 85 | 50 (58.8) | |

| Triple therapy (ICS-LABA-LAMA), n = 84 | 22 (26.2) | |

| SABA on demand, n = 86 | 65 (75.6) | |

| Puffs of SABA, n = 86 | 2.7 (1.6) | |

| No previous treatment, n = 85 | 26 (30.6) | |

| Visit to the primary care physician, n = 82 | 39 (47.6) | |

| Visit to the pneumologist, n = 87 | 45 (51.7) | |

| Need of hospitalization, n = 86 | 18 (20.9) | 0.26 (0.5) |

| Ned of ED admission, n = 86 | 37 (43.0) | 0.7 (1) |

| Exacerbation episodes, n = 86 | 44 (51.2) | 1.26 (1.7) |

| Blood eosinophil count, cells/µL, n = 8 | 340 (290) | |

| Serum IgE level, kU/L, n = 87 | 387 (461) |

| Study Variables | Number of Patients (%) |

|---|---|

| Severity of exacerbation, n = 87 | |

| Mild | 50 (57.5) |

| Moderate | 31 (35.6) |

| Onset of symptoms, n = 85 | |

| Rapid onset | 24 (28.2) |

| Slow onset | 61 (71.8) |

| Sputum analysis, n = 87 | 9 (10.3) |

| Assessment of the cause of exacerbation, n = 86 | 22 (25.5) |

| Arterial oxygen saturation (SaO2), n = 87 | 84 (96.6) |

| Peak expiratory flow (PEF), n = 81 | 17 (21.0) |

| PEF monitored at 1 h, n = 59 | 7 (11.9) |

| PEF monitored at 3 h, n = 59 | 4 (6.8) |

| Treatment | |

| Systemic corticosteroids, n = 83 | 72 (86.7) |

| Oxygen therapy, n = 80 | 40 (50.0) |

| Magnesium sulfate, n = 83 | 2 (2.4) |

| Inhaled bronchodilators, n = 83 | 81 (97.6) |

| Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS), n = 75 | 29 (38.7) |

| ED discharge report | |

| Use of systemic corticosteroids, n = 81 | 62 (76.5) |

| Use of inhaled ICS-LABA, n = 81 | 38 (46.9) |

| Reports with treatment variables only, n = 81 | 30 (37.0) |

| Referral to the primary care physician, n = 75 | 5 (6.7) |

| Referral to a pneumologist, n = 77 | 23 (29.9) |

| Complete (compliant) report, n = 77 | 14 (18.2) |

| Study Variables | Patients (%) | Mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Lung function tests, n = 83 | 34 (41.0) | |

| Self-management plan, n = 76 | 29 (38.2) | |

| Asthma Control Test (ACT), n = 79 | 28 (35.4) | |

| Test of Adherence to Inhalers (TAI), n = 79 | 26 (32.9) | |

| Exacerbation episodes, n = 87 | ||

| At least one episode | 51 (58.6) | |

| Number of episodes | 1.25 (1.7) | |

| Need for inpatient care, n = 86 | 21 (24.4) | |

| Number of hospitalizations | 0.36 (0.7) | |

| Need for ED admission, n = 87 | 36 (41.4) | |

| Number of ED admissions | 0.63 (1) | |

| Follow-up by a primary care physician, n = 83 | 24 (28.9) | |

| Days before a visit with the primary care physician | 16.7 (19) | |

| Follow-up by a pneumologist, n = 85 | 43 (50.6) | |

| Days before a visit with the pneumologist | 75.5 (72) |

| Study Variables | Exacerbation Episodes | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| <2 (n = 63) | ≥2 (n = 24) | p Value | |

| Female patients, n/total (%) | 50/63 (79.4) | 20/24 (83.3) | 0.667 |

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 51.1 (22.2) | 54 (23.9) | 0.490 |

| Never smoker, n/total (%) | 43/60 (71.7) | 15/24 (62.5) | 0.112 |

| Comorbidity, n/total (%) | |||

| Obesity, BMI > 30 kg/m2 | 21/59 (35.6) | 10/24 (41.7) | 0.604 |

| Hypertension | 21/63 (33.3) | 7/24 (29.2) | 0.710 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 7/63 (11.1) | 7/17 (29.2) | 0.041 |

| Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) | 10/61 (16.4) | 5/21 (23.8) | 0.448 |

| Nasal polyposis | 3/50 (6) | 4/22 (18.2) | 0.108 |

| Anxiety | 20/62 (32.3) | 9/23 (39.1) | 0.553 |

| Depression | 13/61 (21.3) | 7/23 (30.4) | 0.381 |

| Mild asthma, n/total (%) | 14/35 (40.0) | 1/19 (5.3) | 0.003 |

| Previous treatment for asthma, n/total (%) | |||

| Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) | 37/62 (59.7) | 19/23 (82.6) | 0.048 |

| ICS, µg budesonide equivalent, mean (SD) | 433.2 (273.3) | 542.3 (380) | 0.229 |

| ICS only | 4/62 (6.5) | 2/23 (8.7) | 0.720 |

| ICS-LABA | 33/62 (53.2) | 18/24 (75) | 0.065 |

| Triple therapy (ICS-LABA-LAMA) | 9/61 (14.8) | 13/23 (56.5) | 0.0001 |

| SABA on demand | 42/63 (66.7) | 23/24 (95.8) | 0.005 |

| Puffs of SABA, mean (SD) | 2.53 (1.28) | 2.95 (1.93) | 0.584 |

| No previous treatment, n/total (%) | 25/62 (40.3) | 2/23 (8.7) | 0.005 |

| Visit to the primary care physician, n/total (%) | 30/60 (50.0) | 9/22 (40.9) | 0.637 |

| Visit to a pneumologist, n/total (%) | 27/63 (42.9) | 18/24 (75.0) | 0.007 |

| Need of hospitalization, n/total (%) | 8/62 (12.9) | 10/24 (41.7) | 0.003 |

| Number of hospitalizations, mean (SD) | 0.15 (0.4) | 0.54 (0.8) | 0.025 |

| Ned of ED admission, n/total (%) | 16/62 (25.8) | 21/24 (87.5) | 0.0001 |

| Number of ED admissions, mean (SD) | 0.31 (0.6) | 1.75 (1.2) | 0.0001 |

| Exacerbation episodes, n/total (%) | 22/62 (35.5) | 22/24 (91.7) | 0.0001 |

| Number of exacerbations, mean (SD) | 0.60 (1.1) | 2.96 (1.9) | 0.0001 |

| Blood eosinophil count, cells/µL, mean (SD) | 354 (280) | 301 (505) | 0.491 |

| Serum IgE level, kU/L, mean (SD) | 428 (441) | 341 (505) | 0.692 |

| Study Variables | Exacerbation Episodes | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| <2 (n = 63) | ≥2 (n = 24) | p Value | |

| Moderate/severe exacerbation, n/total (%) | 25/63 (39.6) | 12/24 (50) | 0.684 |

| Slow onset of symptoms, n/total (%) | 43/62 (69.4) | 18/23 (78.3) | 0.418 |

| Arterial oxygen saturation (SaO2), n/total (%) | 62/63 (98.4) | 22/24 (91.7) | 0.123 |

| Peak expiratory flow (PEF), n/total (%) | 9/57 (15.8) | 8/24 (33.3) | 0.077 |

| PEF monitored at 1 h | 6/43 (14) | 1/16 (6.3) | 0.416 |

| PEF monitored at 3 h | 1/42 (2.4) | 3/17 (17.6) | 0.035 |

| Treatment, n/total (%) | |||

| Systemic corticosteroids | 49/59 (81.7) | 23/24 (95.8) | 0.241 |

| Oxygen therapy | 30/58 (51.7) | 10/22 (45.5) | 0.617 |

| Magnesium sulfate | 2/59 (3.4) | 0/24 (0) | 0.361 |

| Inhaled bronchodilators | 58/60 (96.7) | 23/23 (100) | 0.375 |

| Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) | 23/57 (40.4) | 6/18 (33.3) | 0.594 |

| ED discharge report, n/total (%) | |||

| Use of systemic corticosteroids | 44/58 (75.9) | 18/23 (78.3) | 0.818 |

| Use of inhaled ICS-LABA | 25/58 (43.1) | 13/23 (56.5) | 0.275 |

| Reports with treatment variables only | 19/58 (32.8) | 11/23 (47.8) | 0.205 |

| Referral to the primary care physician | 3/54 (5.6) | 2/21 (9.5) | 0.536 |

| Referral to a pneumologist | 15/56 (26.8) | 8/21 (38.1) | 0.334 |

| Complete (compliant) report | 9/56 (16.1) | 5/21 (23.8) | 0.433 |

| Data at 1-year follow-up, n/total (%) | |||

| Lung function tests | 21/60 (35) | 13/23 (56.5) | 0.074 |

| Self-management plan | 15/54 (27.8) | 14/22 (63.6) | 0.004 |

| Asthma Control Test (ACT) | 14/57 (24.6) | 14/22 (63.6) | 0.001 |

| Test of Adherence to Inhalers (TAI) | 12/57 (21.1) | 14/22 (63.6) | 0.0001 |

| Exacerbation episodes | 27/63 (57.1) | 24/24 (100) | 0.0001 |

| Number of episodes, mean (SD) | 0.43 (0.5) | 3.42 (1.74) | 0.0001 |

| Need for inpatient care | 7/62 (11.3) | 14/24 (58.3) | 0.0001 |

| Number of hospitalizations, mean (SD) | 0.11 (0.32) | 1 (1) | 0.0001 |

| Need for ED admission | 16/63 (25.4) | 20/24 (83.3) | 0.0001 |

| Number of ED admissions, mean (SD) | 0.27 (0.48) | 1.58 (1.35) | 0.0001 |

| Follow-up by a primary care physician | 18/61 (29.5) | 6/22 (27.3) | 0.843 |

| Days before a visit with the primary care physician, mean (SD) | 17.4 (21.5) | 14.3 (10.1) | 0.923 |

| Follow-up by a pneumologist | 25/62 (40.3) | 18/23 (78.3) | 0.002 |

| Days before a visit with the pneumologist, mean (SD) | 87.7 (81) | 58.6 (54) | 0.300 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Martinez Rivera, C.; Hernandez Biette, A.; Núñez Condominas, A.; Garcia Olive, I.; Basagaña Torrentó, M.; Padró Casas, C.; Tapia Barredo, L.; Rosell Gratacós, A. The Impact of the Quality of Care for Adults with Acute Asthma in the Emergency Department of a Tertiary Hospital: A 1-Year Follow-Up Study. Clin. Pract. 2025, 15, 116. https://doi.org/10.3390/clinpract15070116

Martinez Rivera C, Hernandez Biette A, Núñez Condominas A, Garcia Olive I, Basagaña Torrentó M, Padró Casas C, Tapia Barredo L, Rosell Gratacós A. The Impact of the Quality of Care for Adults with Acute Asthma in the Emergency Department of a Tertiary Hospital: A 1-Year Follow-Up Study. Clinics and Practice. 2025; 15(7):116. https://doi.org/10.3390/clinpract15070116

Chicago/Turabian StyleMartinez Rivera, Carlos, Agnes Hernandez Biette, Anna Núñez Condominas, Ignasi Garcia Olive, María Basagaña Torrentó, Clara Padró Casas, Leandro Tapia Barredo, and Antoni Rosell Gratacós. 2025. "The Impact of the Quality of Care for Adults with Acute Asthma in the Emergency Department of a Tertiary Hospital: A 1-Year Follow-Up Study" Clinics and Practice 15, no. 7: 116. https://doi.org/10.3390/clinpract15070116

APA StyleMartinez Rivera, C., Hernandez Biette, A., Núñez Condominas, A., Garcia Olive, I., Basagaña Torrentó, M., Padró Casas, C., Tapia Barredo, L., & Rosell Gratacós, A. (2025). The Impact of the Quality of Care for Adults with Acute Asthma in the Emergency Department of a Tertiary Hospital: A 1-Year Follow-Up Study. Clinics and Practice, 15(7), 116. https://doi.org/10.3390/clinpract15070116