1. Introduction

Obesity is a global epidemic and a major public health concern, with prevalence rates rising sharply in many countries, including Saudi Arabia [

1]. Obese individuals are at increased risk for a spectrum of comorbidities, such as cardiovascular disease, hyperlipidemia, type 2 diabetes, and gallstone disease (cholelithiasis) [

2]. Among these, gallstone formation is particularly noteworthy due to its association with rapid weight loss, which commonly follows very low-calorie diets or bariatric surgery interventions [

3].

Gallbladder disease, especially cholecystitis secondary to gallstones, is one of the most frequent surgical problems encountered in general surgery [

4]. Cholelithiasis refers to the presence of abnormal concretions (gallstones) within the gallbladder, with obesity recognized as a significant risk factor for their development [

5]. The pathogenesis of gallstones in obese individuals is multifactorial, involving cholesterol supersaturation of bile, impaired gallbladder motility, and metabolic alterations [

6]. Rapid weight loss, as seen after bariatric procedures, further exacerbates these risks by enhancing cholesterol mobilization and altering biliary composition [

7,

8].

Bariatric surgery, including sleeve gastrectomy (SG) and Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass (RYGB), is the most effective long-term intervention for obesity and its related comorbidities [

9]. However, these procedures are associated with a substantial risk of gallstone formation, particularly within the first two years postoperatively [

3,

7]. The incidence of gallstones after bariatric surgery varies widely, with rates reported between 10.4% and 52.8% in the first postoperative year, depending on the surgical technique and patient population [

3,

10]. Notably, RYGB is generally associated with a higher risk of cholelithiasis compared to SG, likely due to greater and more rapid weight loss, as well as potential injury to the hepatic branch of the vagus nerve during surgery, which can impair gallbladder motility and promote bile stasis [

10].

Most gallstones formed postoperatively are cholesterol stones, resulting from bile supersaturation, reduced bile acid secretion, increased mucus production, and decreased gallbladder emptying. Symptomatic gallstones can lead to significant morbidity, including biliary colic, cholecystitis, cholangitis, pancreatitis, and, in rare cases, gallbladder carcinoma. While some patients remain asymptomatic, the risk of progression to severe complications necessitates vigilant postoperative monitoring and management [

11,

12].

Preventive strategies for gallstone formation after bariatric surgery include pharmacological interventions such as ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA), which has demonstrated efficacy in reducing gallstone incidence and the need for subsequent cholecystectomy [

3]. Prophylactic cholecystectomy during bariatric surgery is another consideration, particularly for patients with pre-existing gallstones, though its routine use remains debated due to operative risks and resource implications [

13]. Dietary factors, including increased fiber, healthy fats, and certain supplements, may also play a role in reducing gallstone risk, but evidence for their effectiveness in the bariatric population is limited [

14,

15,

16].

Despite the global and national burden of obesity and gallstone disease, there is a notable lack of region-specific data, particularly in Northern Saudi Arabia [

17]. Existing studies have predominantly focused on Western or central regions, with little attention to the unique demographic, dietary, and healthcare factors influencing gallstone incidence in the Northern Border Region. This gap in the literature underscores the need for localized research to inform clinical practice and optimize postoperative care for bariatric patients in this area.

Therefore, the present cross-sectional study aims to determine the incidence of gallstone formation in obese patients following bariatric surgery in the Northern Border Region of Saudi Arabia. By elucidating the frequency and risk factors associated with post-bariatric cholelithiasis in this specific population, our findings will contribute valuable insights to the development of tailored postoperative management strategies, ultimately improving patient outcomes and reducing the burden of gallstone-related complications in this high-risk group.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

This cross-sectional study was conducted in the Northern Border Region of Saudi Arabia to determine the incidence of gallstone formation in obese patients following bariatric surgery. The study adhered to the “STrengthening the Reporting of OBservational studies in Epidemiology” (STROBE) guidelines for observational research [

18]. Data were collected over 3 months (June–September 2024) via several online platforms.

2.2. Participant Selection

The criteria for participant selection from the overall respondents were adults aged 18–60 years with a history of bariatric surgery (including sleeve gastrectomy, Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, adjustable gastric banding, or other bariatric procedures) prior to enrollment, who resided in the specified study region. Participants were excluded if they had a preoperative diagnosis of cholelithiasis, a history of cholecystectomy prior to undergoing bariatric surgery, incomplete response records, or if they refused to participate. Informed written consent was obtained from all participants prior to their participation.

2.3. Sampling Strategy

A convenience sample of at least 323 participants was calculated using Raosoft’s sample size calculator, available at

http://www.raosoft.com/samplesize.html (accessed on 5 March 2024), with a 95% confidence interval, a 5% margin of error, a population size of the Northern area of 390,656, and a response distribution of 70%. The sample reflected demographic diversity across gender, nationality, and socioeconomic status within the region.

2.4. Data Collection

Data were collected using a structured, self-administered questionnaire in Arabic, adapted from previously validated instruments used in studies of gallstone incidence following bariatric surgery in Saudi Arabia to ensure content validity and relevance to the study objectives [

19,

20]. Specialists in bariatric surgery and epidemiology conducted the expert review. The current instrument enabled the collection of detailed demographic, clinical, surgical, and risk factor data necessary to assess the incidence and determinants of gallstone formation after bariatric surgery in the target population.

The questionnaire was distributed electronically via several social media platforms using “Google Forms.” It included the following main components: (1) Informed consent and study information: participants were first provided with detailed information about the study’s purpose, voluntary nature, confidentiality measures, and potential risks and benefits. Informed digital consent was obtained prior to participation. (2) Demographic data: participants reported their sex, age group (18–25, 26–35, 36–45, 46–55, 56–60 years), nationality (Saudi or non-Saudi), place of residence (Northern Region or other), educational level (from uneducated to postgraduate), marital status (single, married, divorced, widowed), occupation (student, employee, unemployed, retired, or other), and height (in centimeters). (3) Bariatric surgery and weight history: information was collected regarding the history of weight loss surgery (yes/no), date of surgery, type of bariatric procedure (gastric sleeve, Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, adjustable gastric banding, or other), and weight measurements at multiple time points: before surgery, at 3 months, 6 months, and 1-year post-surgery, as well as current weight (all in kilograms). (4) Gallstone history and diagnosis: participants were asked about any previous diagnosis of gallstones or cholecystectomy prior to bariatric surgery, whether a preoperative abdominal ultrasound was performed, and if they had been diagnosed with gallstones following surgery. For those diagnosed postoperatively, additional questions addressed the diagnostic modality (ultrasound/sonar) and the time interval from surgery to gallstone development (categorized as 1–3 months, 4–6 months, 7–9 months, 9–12 months, 1.5 years, 2 years, or more than 2 years). (5) Medical and lifestyle risk factors: the questionnaire included items on preoperative comorbidities (hypertension, diabetes, hypercholesterolemia, anemia, thyroid disease, asthma, chronic heart/liver/kidney disease, or other), smoking status (current, former, or never), and use of medications for gallstone prevention or dissolution during the first six months after surgery.

2.5. Variables and Measurements

The primary outcome of this study was the incidence of gallstones, confirmed through imaging techniques. The independent variables included the type of surgical procedure, preoperative body mass index (BMI) for calculating the percentage of total weight loss, and the duration of postoperative follow-up. The confounding control was adjusted for age, sex, and comorbidities.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using the “Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS)” version 27 (IBM SPSS Statistics, Armonk, NY, USA). The distribution of the data was evaluated to determine the most suitable statistical analysis. Analytical approaches included (a) descriptive statistics that were reported as frequencies (%) and/or mean ± SD, (b) bivariate analysis by the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test when appropriate for categorical associations or T-test for continuous data, and (c) logistic regression analysis to determine the predictors of gallstone formation after bariatric surgery. The significance threshold was set at p ≤ 0.05 (two-tailed).

4. Discussion

This cross-sectional study provides important insights into gallstone incidence and associated risk factors after bariatric surgery in Northern Saudi Arabia, a region characterized by high obesity rates and a lack of localized data [

21]. The findings indicate a gallstone incidence of 60.8% within the cohort, significantly exceeding the global range of 18.8–52.8% and similar to the 61.4% reported in Saudi Arabia’s Southern region [

3,

19,

22,

23,

24,

25]. This disparity between the identified local incidence and the global range may indicate variations in surgical practices, genetic factors, or postoperative care protocols across regions [

26]. In this study, 82.4% of gallstone diagnoses were confirmed via ultrasound, consistent with international standards for gallstone detection [

27]. However, the elevated incidence highlights the necessity for proactive surveillance in this population.

4.1. Timing and Mechanisms of Gallstone Formation

In alignment with global trends, nearly 70% of gallstones developed within the first postoperative year, peaking at 7–12 months [

10,

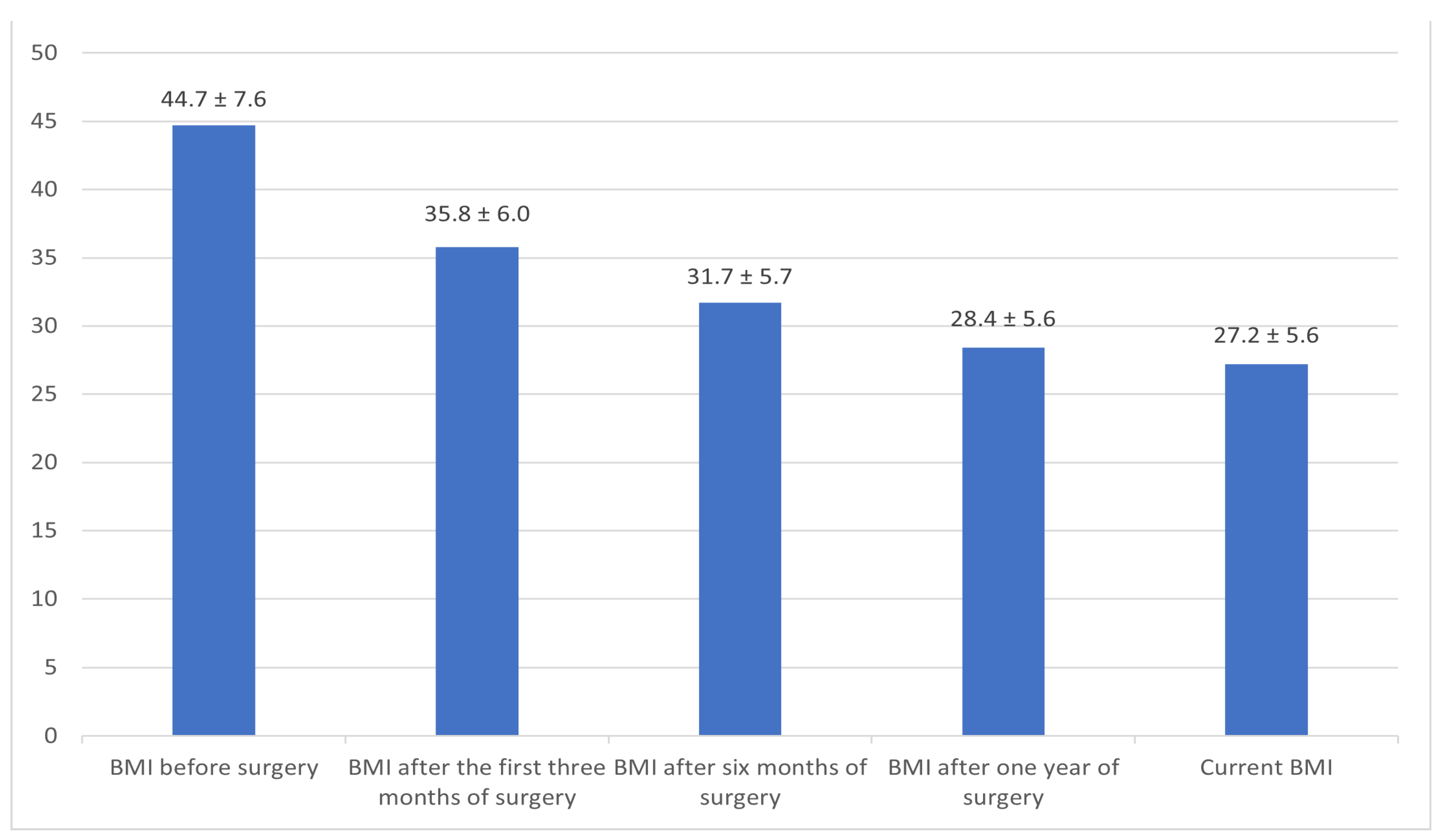

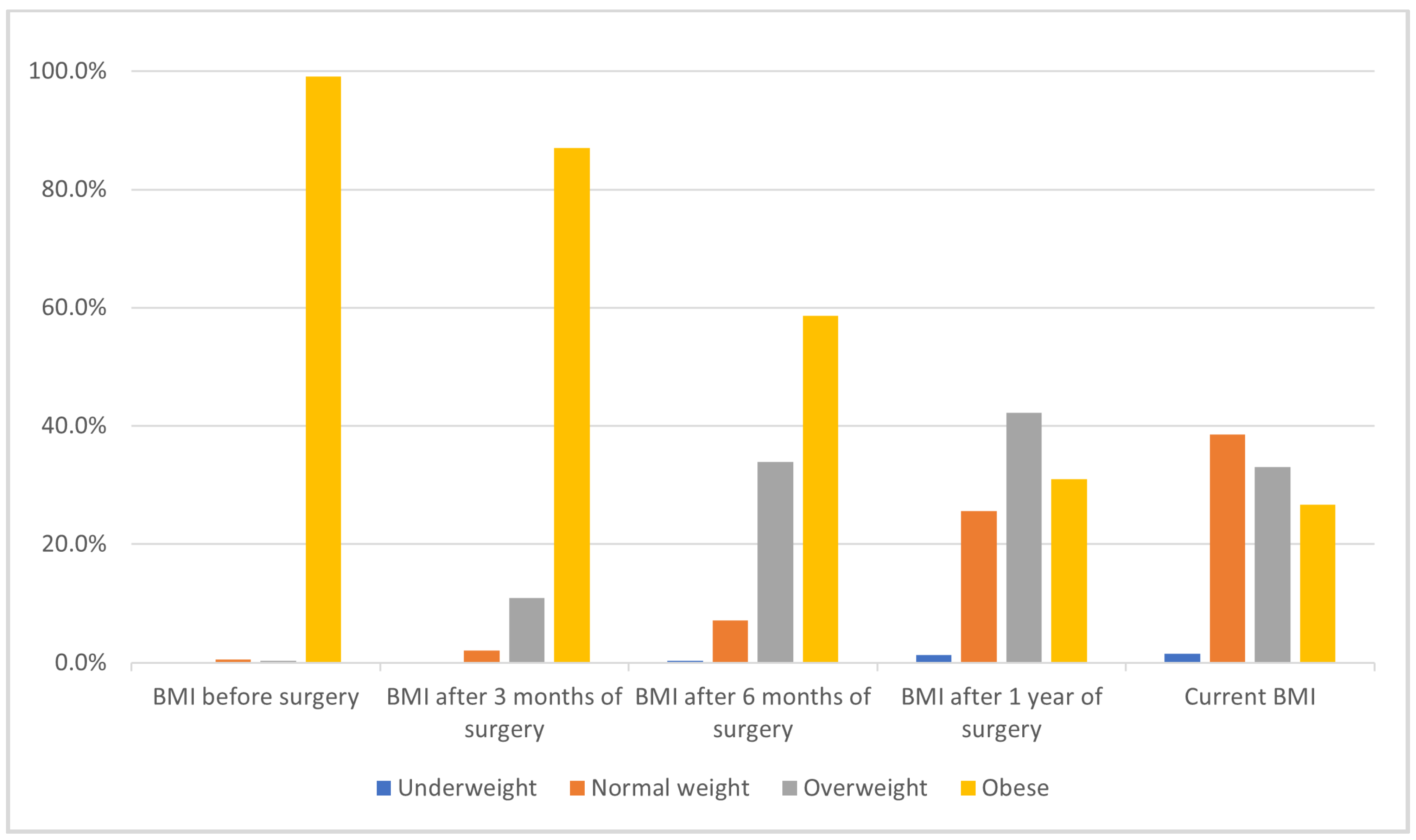

28]. This is consistent with pathophysiological models that associate rapid weight loss, evidenced by significant reductions in BMI at 3, 6, and 12 months, with cholesterol supersaturation, transient biliary stasis, and impaired gallbladder motility during the early postoperative period [

29].

4.2. Demographics and Clinical Risk Factors

Univariate analysis revealed that female sex, age group 26–35 years, marital status (married), and occupation (employee) were significantly associated with increased gallstone risk. However, in the multivariable model, female sex remained an independent predictor (OR: 2.62,

p = 0.003), in line with the literature attributing this to estrogen-mediated effects on cholesterol metabolism [

30]. This contrasts, however, with some studies in which gender differences were less pronounced, suggesting regional variations in metabolic or cultural influences [

23,

31].

4.3. Role of Surgical Technique

Contrary to some earlier studies [

32,

33], the type of bariatric surgery (sleeve gastrectomy, Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, adjustable gastric banding, or other) was not significantly associated with gallstone formation (

p = 0.811 in the adjusted model). However, the small sample size of non-sleeve procedures (e.g., Roux-en-Y: 4.5%, adjustable banding: 3.6%) limits the statistical power to detect procedural differences. While this finding suggests that patient-specific or metabolic factors may outweigh surgical technique in this population, further studies with larger, balanced cohorts are needed to confirm these observations.

4.4. BMI Patterns and Weight Loss

Rapid and substantial postoperative weight loss, as reflected by lower BMI at one year and the most recent follow-up, was associated with gallstone formation in univariate analysis. However, a more detailed examination of BMI categories at one year revealed that the risk of gallstones was highest among patients who transitioned from obesity to the overweight category, while those who achieved normal weight did not have an increased risk compared to those who remained obese. This pattern suggests that the magnitude and rapidity of BMI reduction (i.e., BMI excursion), rather than simply the final BMI category, may play an important role in gallstone pathogenesis. Patients who became overweight may have experienced more abrupt or substantial weight loss, increasing their susceptibility to gallstone formation, whereas those who achieved normal weight might have lost weight more gradually or maintained a healthier metabolic adaptation. In the adjusted model, lower current BMI and longer time since surgery were associated with reduced risk of gallstones. This apparent paradox may be explained by the initial lithogenic effect of rapid weight loss, followed by risk attenuation as weight stabilizes and metabolic adaptation occurs over time. Thus, the period of greatest risk is during the rapid weight loss phase, while sustained lower BMI is ultimately protective. This observation supports the hypothesis that not only the endpoint of weight loss but also the trajectory and rate of BMI change are critical determinants of gallstone risk after bariatric surgery.

4.5. Prophylactic Challenges

Despite guidelines recommending UDCA prophylaxis and promising results associated with its use for gallstone resolution after bariatric surgery [

34,

35,

36,

37], only 11.9% of patients reported using gallstone prevention medication postoperatively. This mirrors other studies where UDCA adherence was suboptimal [

28,

38]. Non-use of prophylaxis was a strong independent risk factor for gallstone formation (OR: 4.12,

p = 0.013), emphasizing the need for greater adherence to preventive strategies. Meta-analysis of randomized control studies demonstrates UDCA reduces cholecystectomy rates and gallstone incidence at three, six, and twelve months when administered prophylactically, emphasizing the need for standardized protocols in Saudi bariatric centers [

39]. Additionally, probiotics (e.g., Lactobacillus) and dietary interventions (e.g., omega-3 supplementation) show promise in modulating bile composition and gut microbiota, offering safer alternatives for long-term management [

40,

41,

42,

43].

4.6. Other Factors

Comorbidities (e.g., hypertension, diabetes), smoking status, and nationality were not significantly associated with gallstone risk in this cohort, highlighting the predominance of sex, weight loss dynamics, and prophylaxis use as the main determinants.

4.7. Clinical and Policy Implications

Given the high incidence and early onset of gallstones, routine ultrasound screening during the first postoperative year is warranted, especially for high-risk groups (females, those with rapid weight loss, and non-users of prophylaxis). Regional guidelines should prioritize early identification and targeted prevention, including patient education and improved access to UDCA and addressing barriers like cost and side effects through subsidized programs or combination therapies with dietary modifications.

4.8. Limitations and Future Directions

This study has several limitations. First, its cross-sectional design precludes causal inferences. Second, the use of convenience sampling and self-reported weights may introduce selection bias (e.g., underrepresentation of certain subgroups) and measurement bias, respectively. Third, the study population, drawn from a single region in Northern Saudi Arabia, may not be fully representative of the broader Saudi or global population, limiting generalizability.

4.9. Future Directions

Future research should adopt prospective designs to (1) track long-term outcomes, such as the progression of asymptomatic gallstones to cholecystitis or pancreatitis, (2) compare UDCA dosing regimens (500 mg vs. 250 mg) in Arab cohorts to optimize adherence and efficacy [

35], and (3) investigate gut microbiota dynamics (e.g., Ruminococcus and Lactobacillus ratios) as predictive biomarkers for gallstone formation [

3].

5. Conclusions

This study highlights a critical public health gap in Northern Saudi Arabia, where the incidence of gallstones after bariatric surgery exceeds global averages. The principal independent risk factors identified were female sex, rapid postoperative weight loss, and lack of prophylactic medication use. While no statistically significant association was observed between the type of bariatric surgery and gallstone risk in this cohort, this finding should be interpreted with caution due to the small number of patients undergoing procedures other than sleeve gastrectomy. Larger, more balanced studies are needed to clarify the impact of surgical techniques. These findings underscore the need for routine postoperative surveillance, targeted patient education, and improved adherence to gallstone prevention strategies, particularly the use of ursodeoxycholic acid, during the high-risk period after surgery. Implementing region-specific guidelines and accessible prophylactic measures can help reduce gallstone-related morbidity and improve long-term outcomes for bariatric patients in this high-risk region.