Urinary Bladder Hamartoma: Narrative Literature Review of an Exotic Pathology and Rare Cause of LUTS

Abstract

1. Introduction

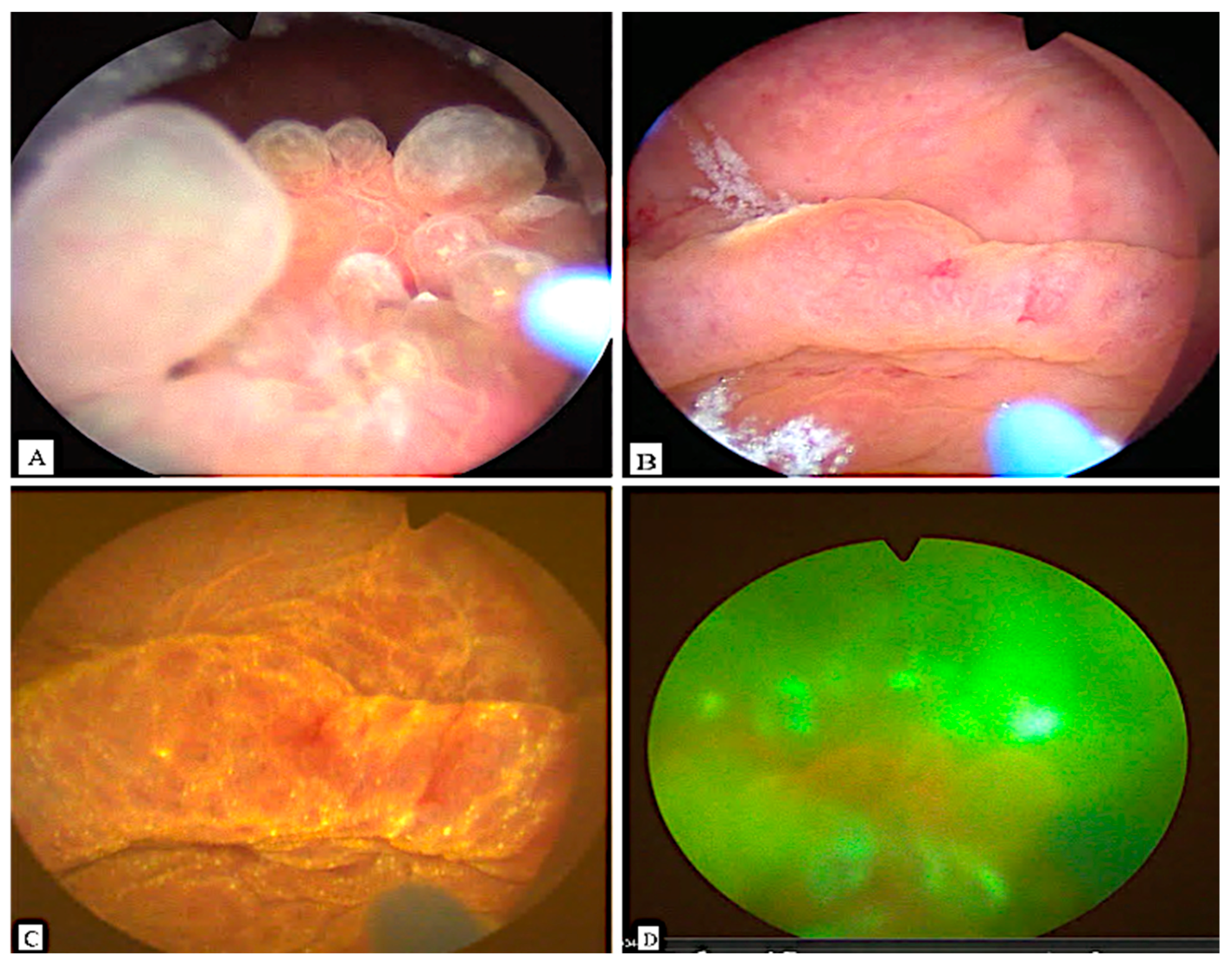

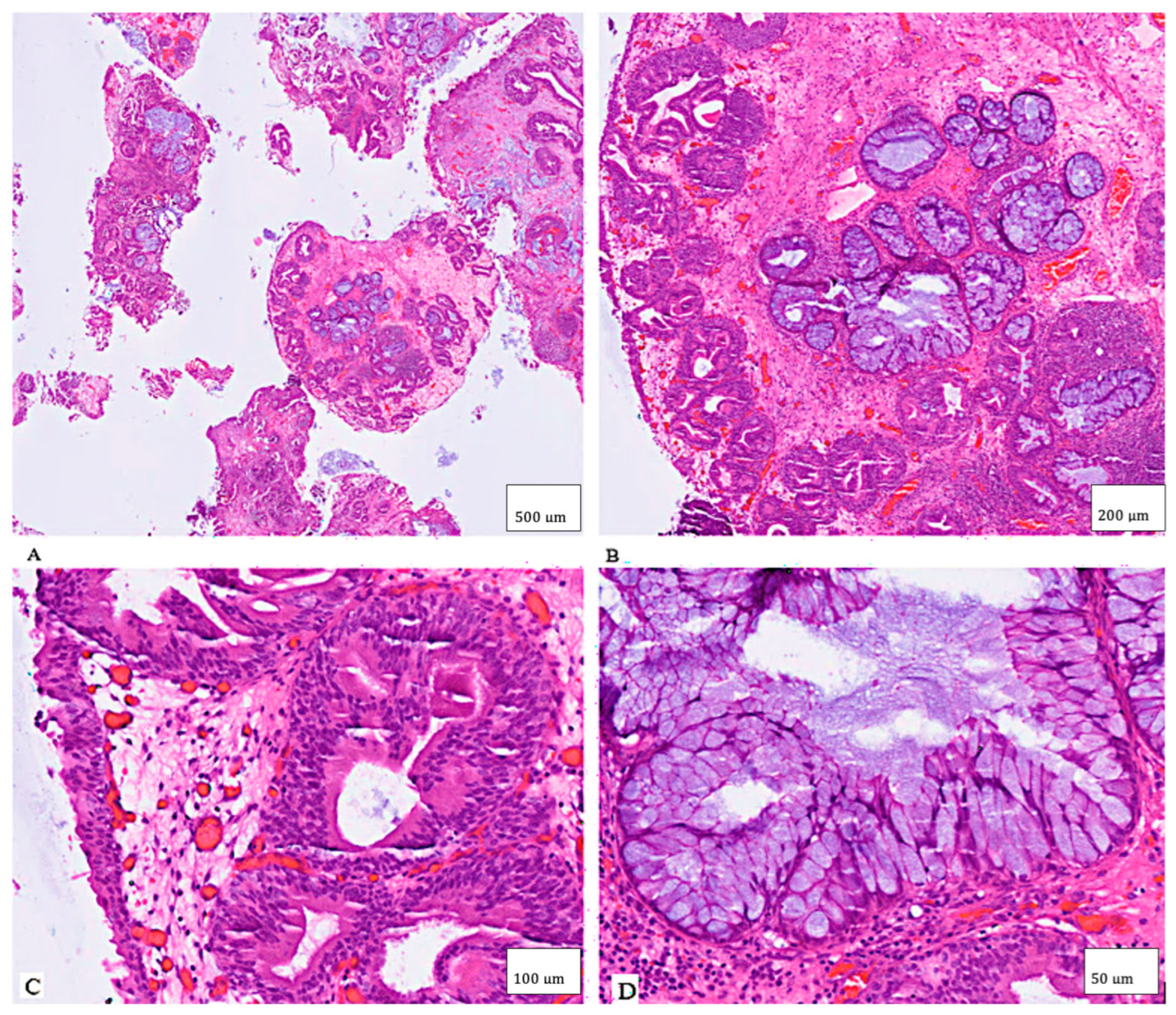

2. Case Presentation

3. Literature Review

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Brancatelli, G.; Midiri, M.; Sparacia, G.; Martino, R.; Rizzo, G.; Lagalla, R. Hamartoma of the urinary bladder: Case report and review of the literature. Eur. Radiol. 1999, 9, 42–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chinyama, C.N. Hamartoma. In Breast Pathology; Sapino, A., Kulka, J., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 135–143. ISBN 978-3-319-62538-6. [Google Scholar]

- Ota, T.; Kawai, K.; Hattori, K.; Uchida, K.; Akaza, H.; Harada, M. Hamartoma of the urinary bladder. Int. J. Urol. 1999, 6, 211–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pescia, C.; Pini, G.; Lopez, G.; Malfatto, M.; Brescia, G.; Tabano, S.; Del Gobbo, A. A Rare Case of Urinary Bladder Hamartoma Clinically Mimicking an Urothelial Carcinoma: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Int. J. Surg. Pathol. 2023, 31, 1572–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, C.; Marchan, J.; Özel, B.; Özel, B. Bladder wall hamartoma: An unusual cause of urinary urgency and frequency. Female Pelvic Med. Reconstr. Surg. 2015, 21, e8–e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, J.; Albeerdy, M.I.; Shaikh, N.A.; Qureshi, A.H. Bladder hamartoma in Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: A rare case report. Afr. J. Urol. 2021, 27, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, A.; Gayaparsad, K.; Engelbrecht, M.J.; Moshokoa, E.; Em, M. Bladder hamartoma: A unique cause of urinary retention in a child with Goldenhar syndrome. Saudi J. Kidney Dis. Transplant. 2013, 24, 89–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, M.P.L.; Ibrahim, S.K.; Rickwood, A.M.K. Hamartoma of the urinary bladder in an infant with Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome. Br. J. Urol. 1990, 65, 106–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moose, L.T.; Garvey, F.K. Hamartoma of the Bladder. J. Urol. 1963, 89, 185–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borski, A.A. Hamartoma of the Bladder. J. Urol. 1970, 104, 718–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keating, M.A.; Young, R.H.; Lillehei, C.W.; Retik, A.B. Hamartoma of the bladder in A 4-year-old girl with hamartomatous polyps of the gastrointestinal tract. J. Urol. 1987, 138, 366–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, C.; Kim, H.; Lee, Y.B.; Song, J.M.; Ro, J.Y. Hamartoma of the urachal remnant. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 1989, 113, 1393–1395. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- McCallion, W.A.; Herron, B.M.; Keane, P.F. Bladder hamartoma. Br. J. Urol. 1993, 72, 382–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duvenage, G.F.; Dreyer, L.; Reif, S.; Bornman, M.S.; Steinmann, C.F. Bladder hamartoma. Br. J. Urol. 1997, 79, 133–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pieretti, A.; Wu, C.-L.; Pieretti, R.V. Bladder Hamartoma in a Fetus: Case Report. Urol. Case Rep. 2014, 2, 154–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Shahwani, N.; Alnaimi, A.R.; Ammar, A.; Al-Ahdal, E.M. Hamartoma of the urinary bladder in a 15-year-old boy. Turk. J. Urol. 2016, 42, 101–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tavora, F.; Kryvenko, O.N.; Epstein, J.I. Mesenchymal tumours of the bladder and prostate: An update. Pathology 2013, 45, 104–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, G.-X.; Weeden, E.M.; Hamele-Bena, D.; Huan, Y.; Unger, P.; Memeo, L.; O’TOole, K. Expression of PAX8 in nephrogenic adenoma and clear cell adenocarcinoma of the lower urinary tract: Evidence of related histogenesis? Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2008, 32, 1380–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López, J.I.; Schiavo-Lena, M.; Corominas-Cishek, A.; Yagüe, A.; Bauleth, K.; Guarch, R.; Hes, O.; Tardanico, R. Nephrogenic adenoma of the urinary tract: Clinical, histological, and immunohistochemical characteristics. Virchows Arch. 2013, 463, 819–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Authors | Ref. | Y | Sex | Age | Localization | Clinical Presentation | Cytology | IHC | Therapy | Outcome | Follow-Up (Months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lathan & Garvey | [9] | 1963 | M | 13 | Left posterior wall with trigone extension | Gross hematuria and pyuria | NA | NA | TUR | No recurrence | 60 |

| Borski | [10] | 1970 | M | 45 | Bladder neck | LUTS | NA | NA | TUR | No recurrence | 6 |

| Keating et al. | [11] | 1987 | F | 4 | Posterior wall | Recurrent UTI in Peutz–Jeghers syndrome | NA | NA | Partial cystectomy | No recurrence | 4 |

| Park et al. | [12] | 1989 | F | 45 | Bladder dome | LUTS | NA | NA | TUR | NA | NA |

| Williams et al. | [8] | 1990 | M | 0.8 | Posterior wall | Hematuria in Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome | NA | NA | TUR | No recurrence | 18 |

| McCallion et al. | [13] | 1993 | M | 41 | Trigone | LUTS with hematuria | NA | NA | TUR | No recurrence | 60 |

| Duvenage et al. | [14] | 1997 | M | 19 | Right posterior wall | Hematuria with schistosomiasis | NA | Muscle markers negative | TUR | No recurrence | 5 |

| Ota et al. | [3] | 1999 | F | 58 | Left posterior wall, invasive appearance on imaging | LUTS | No malignant cells | NA | TUR + partial cystectomy | No recurrence | 36 |

| Brancatelli et al. | [1] | 1999 | M | 30 | Right posterior wall, intramural | Gross hematuria, fever | NA | NA | Partial cystectomy | No recurrence | 12 |

| Adam et al. | [7] | 2013 | M | 5 | Trigone | LUTS with Goldenhar syndrome | NA | NA | TUR | No recurrence | 2 |

| Pieretti et al. | [15] | 2014 | M | 0.2 | Anterior wall | Prenatal detection | NA | S100−, HMB45−, keratin−, SMA+ | TUR | No recurrence | 18 |

| Murray et al. | [5] | 2015 | F | 51 | Bladder neck | LUTS | NA | NA | Transvaginal excision | No recurrence | 2 |

| Al Shahwani et al. | [16] | 2016 | M | 15 | Left lateral wall | LUTS | NA | NA | TUR | No recurrence | NA |

| Kumar et al. | [6] | 2021 | M | 20 | Bladder neck | LUTS in Peutz–Jeghers syndrome | NA | NA | TUR + mitomycin | NA | NA |

| Pescia et al. | [4] | 2022 | F | 54 | Left posterior wall | Incidental finding | No malignant cells | keratin 8/18+, EMA+, p63+, keratin 7 focal+, PAX8− | TUR | NA | NA |

| Present case | NA | 2023 | M | 22 | Bladder neck | LUTS | No malignant cells | NA | Partial TUR | No recurrence of symptoms | 14 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kanaan, M.R.; Akkoyun, M.; Lafos, M.; Kuczyk, M.A.; Tezval, H. Urinary Bladder Hamartoma: Narrative Literature Review of an Exotic Pathology and Rare Cause of LUTS. Clin. Pract. 2025, 15, 218. https://doi.org/10.3390/clinpract15120218

Kanaan MR, Akkoyun M, Lafos M, Kuczyk MA, Tezval H. Urinary Bladder Hamartoma: Narrative Literature Review of an Exotic Pathology and Rare Cause of LUTS. Clinics and Practice. 2025; 15(12):218. https://doi.org/10.3390/clinpract15120218

Chicago/Turabian StyleKanaan, Mohammed Rafea, Meryem Akkoyun, Marcel Lafos, Markus Antonius Kuczyk, and Hossein Tezval. 2025. "Urinary Bladder Hamartoma: Narrative Literature Review of an Exotic Pathology and Rare Cause of LUTS" Clinics and Practice 15, no. 12: 218. https://doi.org/10.3390/clinpract15120218

APA StyleKanaan, M. R., Akkoyun, M., Lafos, M., Kuczyk, M. A., & Tezval, H. (2025). Urinary Bladder Hamartoma: Narrative Literature Review of an Exotic Pathology and Rare Cause of LUTS. Clinics and Practice, 15(12), 218. https://doi.org/10.3390/clinpract15120218