Association Between Parents’ Self-Perceived Oral Health Knowledge and the Presence of Dental Caries in Their Children

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

- Parents (male or female) with at least two children.

- Children between 4 and 14 years of age.

- Signed informed consent and assent of the minors and their legal guardian.

- Children had to be in good general health, without chronic systemic conditions.

3. Statistical Analysis

- Chi-square independence test.

- Odds ratio (OR) calculation with 95% confidence interval.

4. Results

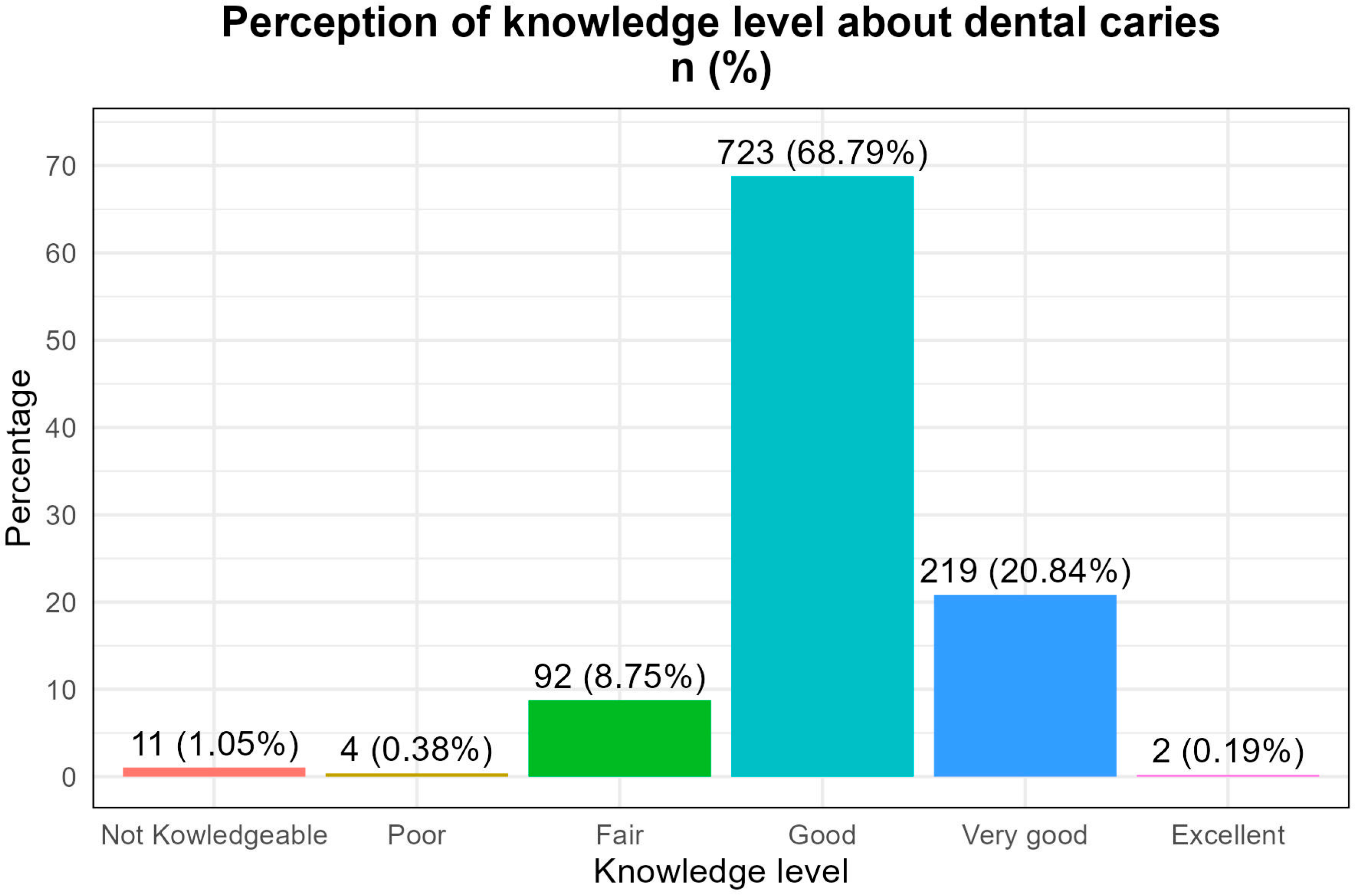

- Good: 68.8%

- Very good: 20.8%

- Excellent: 0.19%

- Fair: 8.75%

- Not knowledgeable: 1.05%

- Terrible: 0.38%

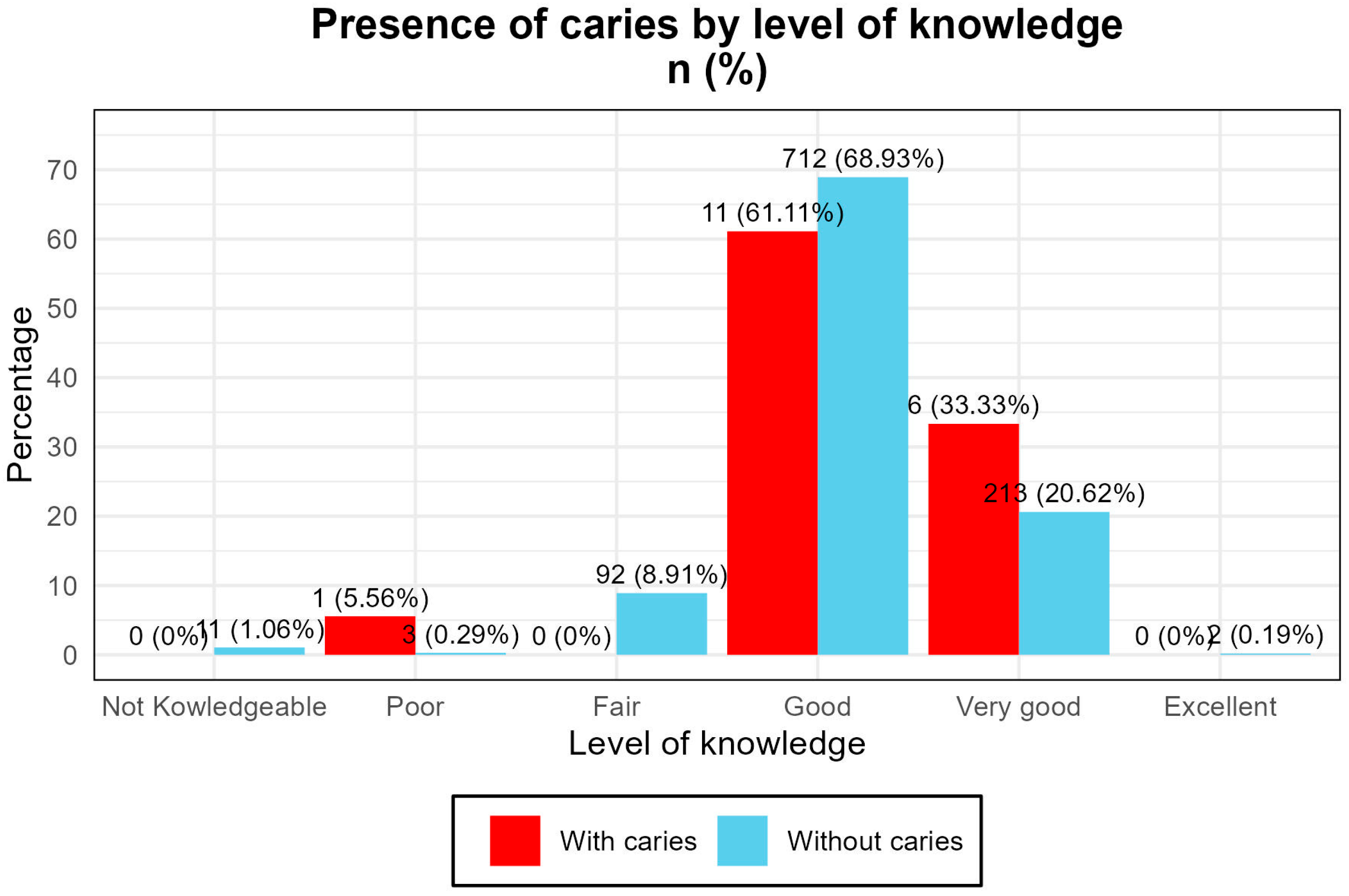

- A total of 61.1% of children with caries had parents who rated their knowledge as “good”.

- A total of 33.3% had parents who rated it as “very good”.

- Only one case was found among parents who rated their knowledge as “terrible”. (Figure 1)

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

7. Limitations of the Study

- The cross-sectional design prevents causal inference.

- The reliance on self-perception may introduce bias.

- The exclusion of non-cavitated lesions may underestimate caries prevalence.

8. Implications for Public Health

- Educational strategies should target parents with low self-perceived knowledge.

- Programs must be culturally adapted and integrated into schools and communities.

- Future research should include objective assessments of knowledge and longitudinal designs to evaluate behavioral outcomes.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ORs | odds ratios |

| MSP | Health Public |

| OCP | heavy crude oil pipeline |

| OHIP-14 | Oral Health Impact Profile |

| OIDP | Oral Impacts on Daily Performance |

| CPQ | Child Perceptions Questionnaire |

| OHQoL-UK | Oral Health-Related Quality of Life—UK |

References

- De Stefani, A.; Bruno, G.; Irlandese, G.; Barone, M.; Costa, G.; Gracco, A. Oral health-related quality of life in children using the child perception questionnaire CPQ11-14: A review. Eur. Arch. Paediatr. Dent. 2019, 20, 425–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, M.; Kabani, F.; Cotter, J. A review of the effects of oral health media hype on clients’ perception of treatment. Can. J. Dent. Hyg. 2022, 56, 31–38. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Hong, J.; Xiong, D.; Zhang, L.; Li, Y.; Huang, S. Are parents’ education levels associated with either their oral health knowledge or their children’s oral health behaviors? A survey of 8446 families in Wuhan. BMC Oral Health 2020, 20, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abanto, J.; Diaz, S.; Veloso, A.; Garza, M.; Reis, V.; Guinot, F. Association between socioeconomic factors, attitudes and beliefs regarding the primary dentition and caries in children aged 1–5 years of Brazilian and Colombian parents. Eur. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2024, 25, 258–265. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tomás, C.C.; Oliveira, E.; Sousa, D.; Uba, M.; Furtado, G.; Rocha, C. Proceedings of the 3rd IPLeiria’s International Health Congress: Leiria, Portugal. 6–7 May 2016. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2016, 16 (Suppl. S3), 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elwenspoek, M.M.; Thom, H.; Sheppard, A.L.; Keeney, E.; O’Donnell, R.; Jackson, J. Defining the optimum strategy for identifying adults and children with coeliac disease: Systematic review and economic modelling. Health Technol. Assess. 2022, 26, 1–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaffee, B.W.; Rodrigues, P.H.; Kramer, P.F.; Vítolo, M.R.; Feldens, C.A. Oral health-related quality-of-life scores differ by socioeconomic status and caries experience. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2017, 45, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiorillo, L. Oral Health: The First Step to Well-Being. Medicina 2019, 55, 676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, S.A.; Quinonez, R.B.; Deutchman, M.; Conklin, C.E.; Rizzolo, D.; Rabago, D. Integrating Oral Health into Health Professions School Curricula. Med. Educ. Online 2022, 27, 2090308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homayouni, A.; Pourjafar, H.; Mirzakhani, E. A comprehensive review of the application of probiotics and postbiotics in oral health. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1120995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.P.; Hsin, H.T.; Wang, B.L.; Wang, Y.C.; Yu, P.C.; Huang, S.H. Gender differences in oral health among prisoners: A cross-sectional study from Taiwan. BMC Oral Health 2023, 23, 900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamster, I.B. The 2021 WHO Resolution on Oral Health. Int. Dent. J. 2021, 71, 279–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corchuelo, J.; González, G.J.; Casas, A. Factors Associated with Self-Perception in Oral Health of Pregnant Women. Health Educ. Behav. 2022, 49, 516–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putri, T.N.; Indriyanti, R.; Setiawan, A.S. A descriptive study on oral hygiene practice and caries increment in children with growth stunting. Front. Oral Health 2023, 4, 1236228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadassi, H.; Millo, I.; Yaari, M.; Kerem, E.; Katz, M.; Porter, B. Enhancing the primary care pediatrician’s role in managing psychosocial issues: A cross sectional study of pediatricians and parents in Israel. Isr. J. Health Policy Res. 2022, 11, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Alkhers, N.; Kopycka, D.T.; Billings, R.J.; Wu, T.T.; Castillo, D.A. Prenatal Oral Health Care and Early Childhood Caries Prevention: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Caries Res. 2019, 53, 411–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nimbeni, S.B.; Al Mejmaj, D.I.; Alrashidi, R.M. Association between Demographic Factors Parental Oral Health Knowledge and their Influences on the Dietary and Oral Hygiene Practices followed by Parents in Children of 2–6 Years in Buraidah City Saudi Arabia: A Pilot Study. Int. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 2022, 15, 407–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, D.; Kumar, A.; Kumar, V.; Sethi, S. Oral health perception and plight of patients of schizophrenia. Int. J. Dent. Hyg. 2021, 19, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, P.; Chua, H.; Ekambaram, M.; Lo, E.; Yiu, C. Risk predictors of early childhood caries increment a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Evid. Based Dent. Pract. 2022, 22, 101732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayre, J.; Pearce, H.; Khera, R.; Lunn, A.; Ford, J. Health impacts of the Sure Start programme on disadvantaged children in the UK: A systematic review. BMJ Open 2025, 15, e089983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napoletano, G.; Putrino, A.; Marinelli, E.; Zaami, S.; De Paola, L. Dental Identification System in Public Health: Innovations and Ethical Challenges: A Narrative Review. Healthcare 2024, 12, 1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, C.; Muñoz, M.; Núñez, E.; Hernández, R. Recurrent Aphthous Stomatitis Affects Quality of Life. A Case-Control Study. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dent. 2022, 14, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daley, S.F.; Gonzalez, D.; Bethencourt, A.; Afzal, M. Child Abuse and Neglect. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Kim, B. The Effects of the Expansion of Dental Care Coverage for the Elderly. Healthcare 2024, 12, 1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pollachi, G.P.; Asokan, S.; Balaraman, C.; Viswanath, S.; Thoppe, Y.K. Pediatrician’s perception of oral health in children—A qualitative study. J. Indian Soc. Pedod. Prev. Dent. 2023, 41, 239–245. [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz, A.; Kleinman, D.; Child, W.; Radice, S.; Maybury, C. Perceptions of Dental Hygienists and Dentists about Preventing Early Childhood Caries: A Qualitative Study. J. Dent. Hyg. 2017, 91, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Soares, R.; da Rosa, S.; Moysés, S.; Rocha, J.; Bettega, P.; Werneck, R. Methods for prevention of early childhood caries: Overview of systematic reviews. Int. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2021, 31, 394–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauricio, H.; Moreira, R. Self-perception of oral health by indigenous people: An analysis of latent classes. Cien. Saude. Colet. 2020, 25, 3765–3772, (In Portuguese, English). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Silva, A.; Barbosa, T.; Gavião, M. Parental Perception of the Oral Health-Related Quality of Life of Children and Adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Procopio, S.; Tavares, M.; Carrada, C.; Ribeiro, F.; Ribeiro, R.; Paiva, S.M. Perceptions of Parents/Caregivers About the Impact of Oral Conditions on the Quality of Life of Children and Adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorder. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2024, 54, 4278–4287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, G.; Firmino, R.; Nóbrega, W.; d’Ávila, S. Oral habits, sociopsychological orthodontic needs, and sociodemographic factors perceived by caregivers impact oral health-related quality of life in children with and without autism? Int. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2024, 34, 593–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goswami, M.; Bhatara, S.; Bhatara, M.; Singh, S.R. Parental perspectives on oral health-related quality of life in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review. Spec. Care Dent. 2024, 44, 700–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jawdekar, A.M.; Kamath, S.; Kale, S.; Mistry, L. Assessment of oral health-related quality of life (OHRQoL) in children with molar incisor hypomineralization (MIH)—A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. J. Indian Soc. Pedod. Prev. Dent. 2022, 40, 368–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, M.U.C.; Freitas Miranda Filho, A.E.; Molena, K.F.; Silva, L.A.B.D.; Stuani, M.B.S.; Queiroz, A.M. The impact of caregiver training on the oral health of people with disabilities: A systematic review. Spec. Care Dent. 2025, 45, e13072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saccomanno, S.; De Luca, M.; Saran, S.; Petricca, M.; Caramaschi, E.; Mastrapasqua, R. The importance of promoting oral health in schools: A pilot study. Eur. J. Transl. Myol. 2023, 33, 11158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puthiyapurayil, J.; Anupam, T.V.; Syriac, G.; Najmunnisa, T. Parental perception of oral health related quality of life and barriers to access dental care among children with intellectual needs in Kottayam, central Kerala-A cross sectional study. Spec. Care Dent. 2022, 42, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scalioni, F.; Carrada, C.; Abreu, L.; Ribeiro, R.; Paiva, S. Perception of parents/caregivers on the oral health of children/adolescents with Down syndrome. Spec. Care Dent. 2018, 38, 382–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karam, S.; Costa, F.; Correa, M.; Bertoldi, A.; Barros, F.; Demarco, F. Socioeconomic inequalities related to maternal perception of children’s oral health at age 4: Results of a birth cohort. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2023, 51, 872–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menoncin, B.; Crema, A.; Ferreira, F.; Zandoná, A.; Menezes, J.; Fraiz, F.C. Parental oral health literacy influences preschool children’s utilization of dental services. Braz. Oral Res. 2023, 37, e090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freire, M.; Graça, S.; Dias, S.; Mendes, S. Oral health-related quality of life in portuguese pre-school children: A cross-sectional study. Eur. Arch. Paediatr. Dent. 2022, 23, 945–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Count | % | Accumulated% |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Man | 374 | 35.59 | 35.59 |

| Woman | 677 | 64.41 | 100.00 |

| Age | |||

| to 4–8 years | 375 | 35.68 | 35.68 |

| to 8–12 years | 325 | 30.92 | 66.60 |

| to 12–14 years | 351 | 33.40 | 100.00 |

| Presence of caries | |||

| With cavities | 18 | 1.71 | 1.71 |

| No cavities | 1033 | 98.29 | 100.00 |

| Relation | Statistical | df | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Presence of caries vs. knowledge | 16.245 | 5 | 0.0062 |

| Relation | Odds Ratio | IC95% [LI − LS] | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low knowledge and presence of caries | 18.18 | [1.80, 183.75] | 0.014 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Coello Hidalgo, A.; Alvear Miquilena, A.; Tipan Venegas, E.; Sandoval Sánchez, Y.; Quiguango Farias, D.; Rodriguez Tates, M.; Velasquez Ron, B. Association Between Parents’ Self-Perceived Oral Health Knowledge and the Presence of Dental Caries in Their Children. Clin. Pract. 2025, 15, 204. https://doi.org/10.3390/clinpract15110204

Coello Hidalgo A, Alvear Miquilena A, Tipan Venegas E, Sandoval Sánchez Y, Quiguango Farias D, Rodriguez Tates M, Velasquez Ron B. Association Between Parents’ Self-Perceived Oral Health Knowledge and the Presence of Dental Caries in Their Children. Clinics and Practice. 2025; 15(11):204. https://doi.org/10.3390/clinpract15110204

Chicago/Turabian StyleCoello Hidalgo, Andrea, Ana Alvear Miquilena, Esteven Tipan Venegas, Yeslith Sandoval Sánchez, Diego Quiguango Farias, Maria Rodriguez Tates, and Byron Velasquez Ron. 2025. "Association Between Parents’ Self-Perceived Oral Health Knowledge and the Presence of Dental Caries in Their Children" Clinics and Practice 15, no. 11: 204. https://doi.org/10.3390/clinpract15110204

APA StyleCoello Hidalgo, A., Alvear Miquilena, A., Tipan Venegas, E., Sandoval Sánchez, Y., Quiguango Farias, D., Rodriguez Tates, M., & Velasquez Ron, B. (2025). Association Between Parents’ Self-Perceived Oral Health Knowledge and the Presence of Dental Caries in Their Children. Clinics and Practice, 15(11), 204. https://doi.org/10.3390/clinpract15110204