Abstract

Neuroimaging can provide significant benefits in evaluating patients with movement disorders associated with drugs. This literature review describes neuroimaging techniques performed to distinguish Parkinson’s disease from drug-induced parkinsonism. The dopaminergic radiotracers already reported to assess patients with drug-induced parkinsonism are [123I]-FP-CIT, [123I]-β-CIT, [99mTc]-TRODAT-1, [18F]-DOPA, [18F]-AV-133, and [18F]-FP-CIT. The most studied one and the one with the highest number of publications is [123I]-FP-CIT. Fludeoxyglucose (18F) revealed a specific pattern that could predict individuals susceptible to developing drug-induced parkinsonism. Another scintigraphy method is [123I]-MIBG cardiac imaging, in which a relationship between abnormal cardiac imaging and normal dopamine transporter imaging was associated with a progression to degenerative disease in individuals with drug-induced parkinsonism. Structural brain magnetic resonance imaging can be used to assess the striatal region. A transcranial ultrasound is a non-invasive method with significant benefits regarding costs and availability. Optic coherence tomography only showed abnormalities in the late phase of Parkinson’s disease, so no benefit in distinguishing early-phase Parkinson’s disease and drug-induced parkinsonism was found. Most methods demonstrated a high specificity in differentiating degenerative from non-degenerative conditions, but the sensitivity widely varied in the studies. An algorithm was designed based on clinical manifestations, neuroimaging, and drug dose adjustment to assist in the management of patients with drug-induced parkinsonism.

Keywords:

dopamine transporter; DAT; dopaminergic imaging; DIP; PET; SPECT; SWEED; SWIDD; neurotransmitter; drug-induced movement disorder 1. Introduction

Drug-induced movement disorders impact a significant portion of the population. At least one percent of the population is estimated to suffer from tremors or ataxia secondary to medications [1,2]. In this context, there is a significant burden related to the high cost of extensive diagnostic workup, hospitalization, increased healthcare expenditures, and lost workdays due to drug-induced movement disorders. More than five percent of subjects initially presenting with Parkinson’s disease are commonly later diagnosed with drug-induced parkinsonism [3].

Neuroleptics are the most common class of medications associated with drug-induced parkinsonism [4]. They may block dopaminergic D2 receptors in the postsynaptic neurons. The prevalence of drug-induced parkinsonism in individuals managed with neuroleptics in the literature widely varies from 15% to 60% [2,5]. In this context, the duration of neuroleptic therapy, neuroleptic doses, and genetic predisposition of individuals may significantly influence the development of drug-induced parkinsonism [6]. Drug-induced parkinsonism can occur secondary to many agents, including antibiotics, antidepressants, antiseizure medications, and calcium channel blockers [7,8].

An inaccurate or delayed diagnosis of drug-induced parkinsonism may result in ineffective treatment and expose patients to side effects, impacting their quality of life. In this context, the clinical differentiation between Parkinson’s disease and drug-induced parkinsonism usually requires discontinuing the offending medication for a long period, which is often challenging and, in some cases, not feasible, such as in active neuropsychiatric disorders. Moreover, a levodopa trial could be effective in suspected subclinical parkinsonism, especially in parkinsonism secondary to dopamine-blocking agents [9].

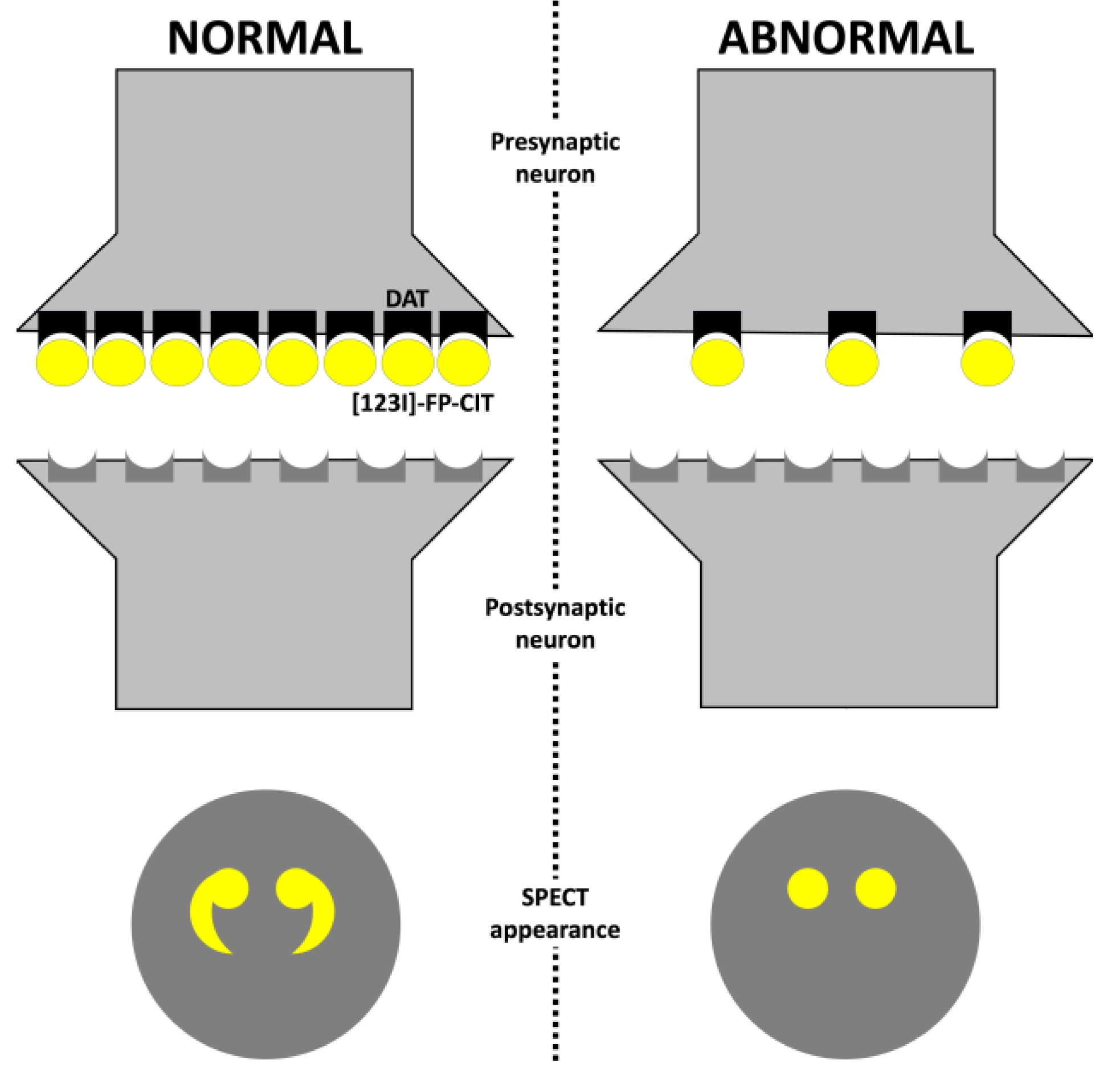

Neuroimaging could provide significant benefits for patients presenting with drug-induced parkinsonism, mainly in those individuals with similar and undifferentiated clinical manifestations to Parkinson’s disease. Neuroimaging techniques have different parameters for assessing brain regions’ structure, function, metabolism, and receptor sites (Figure 1). This literature review describes neuroimaging studies to distinguish Parkinson’s disease from drug-induced parkinsonism.

Figure 1.

Neuroimaging characteristics. Abbreviations: CT, computed tomography; fMRI, functional magnetic resonance imaging; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; MRS, magnetic resonance spectroscopy; PET, positron emission tomography; and SPECT, single-photon emission computed tomography.

2. Dopamine Radiotracers

2.1. History

Several radiotracers were studied in the 1980s. The researchers’ major problems in designing these radioligands were that the agents had an unreliable regional distribution, lower affinity to specific proteins, or slow and long-continued accumulation [10]. The binding of the first radiotracers was relatively non-selective to dopamine, with a similar affinity to other neurotransmitters like noradrenaline and serotonin. Almost a decade later, studies with dopamine transporter (DAT) radiotracers, mainly [123I]-β-CIT, showed significant differences on the valid distribution and affinity to DAT between healthy controls and parkinsonism secondary to 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MTPT) [11].

The cerebellum is usually a reference tissue for assessing the development of new dopamine transporter radiotracers because it does not have these membrane proteins [12]. Among the first radiotracers developed, [123I]-β-CIT has the highest striatal–cerebellum uptake ratio, but the equilibrium for this technique is only achieved after 24 h, which results in delayed scanning. Therefore, researchers developed [123I]-FP-CIT and [123I]-Altropane to shorten the time between intravenous injection and scanning. Nevertheless, these techniques have lower striatal–cerebellum uptake ratios when compared to [123I]-β-CIT [13].

The [123I]-FP-CIT Study Group compared the striatal DAT imaging in individuals with probable Parkinson’s disease and patients with essential tremor, in which the sensitivity and specificity were greater than 90%, to differentiate these two pathologies [14]. This study’s results showed the significance of neuroimaging in the assessment of movement disorders, suggesting the inclusion of DAT radiotracers to support the diagnosis of uncertain cases of parkinsonism. Three further pivotal studies evaluated the specificity of DAT imaging for diagnosing Parkinson’s disease. First, the Clinically Uncertain Parkinsonian Syndromes (CUPS) study compared single-time imaging and evaluation [15]. Second, the Query study compared clinical diagnosis to imaging over six months [16]. Third, there was the European multicenter study in which the clinical diagnosis was prospectively compared to imaging over three years [17]. Interestingly, these studies revealed that clinicians’ assessment, compared to imaging, has a high sensitivity and low specificity in diagnosing Parkinson’s disease.

Some years later, 99mTc-TRODAT-1, a metastable technetium-based tropane tracer, was developed. This chemical compound can accumulate faster than other tropane tracers, but it has a low striatal–cerebellum ratio and is not well-extracted by the brain [13]. Therefore, this imaging technique provides a lower accuracy of the subtle dopamine transporter loss, which can result in more false-negative results in individuals with early Parkinson’s disease.

Cocaine analogues were the most studied radiotracers for assessing dopaminergic transport. These analogues are artificially constructed novel chemical compounds from cocaine’s molecular structure. The mechanism of action of cocaine is not yet completely understood. The main characteristic of the purpose for using cocaine analogues as radiotracers is that cocaine can bind tightly at the dopamine transporters blocking the transporter’s function [18].

The molecules studied, like cocaine analogues, were attached to several radionuclides. There are four main radionuclides, each with a specific chemical step for including the carried molecules (Table 1) [19]. The properties of the radionuclides are important because they define the protocols of the techniques, such as the time of scanning after contrast infusion and the washing-out period of some medications. It is noteworthy that positron emission tomography (PET) scans are superior to single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) for imaging DATs. It is believed that the high energy of positrons provides a higher resolution, resulting in a better image quality with widespread clinical applications [20]. Nevertheless, the majority of the studies in the literature about parkinsonism, including those in patients with drug-induced parkinsonism, performed SPECTs with 123I and 99mTc.

Table 1.

Properties of selected radionuclides.

A basic principle should be remembered when assessing dopaminergic radiotracers in parkinsonism. There are significant limitations of the different neuroimaging techniques developed, mainly the dose related to DAT. They can categorize individuals with parkinsonism into degenerative and non-degenerative diseases [21]. In this context, the degenerative diseases may have a similar degenerative pattern as Parkinson’s disease, including corticobasal degeneration, dementia with Lewy bodies, multiple system atrophy parkinsonian type, and progressive supranuclear palsy. On the other hand, the non-degenerative conditions that can be encountered are drug-induced parkinsonism, tremor related to metabolic or functional causes, dystonic tremor, essential tremor, and vascular parkinsonism [22].

2.2. Mechanism and General Description of Dopamine Transporter (DAT) Radiotracers

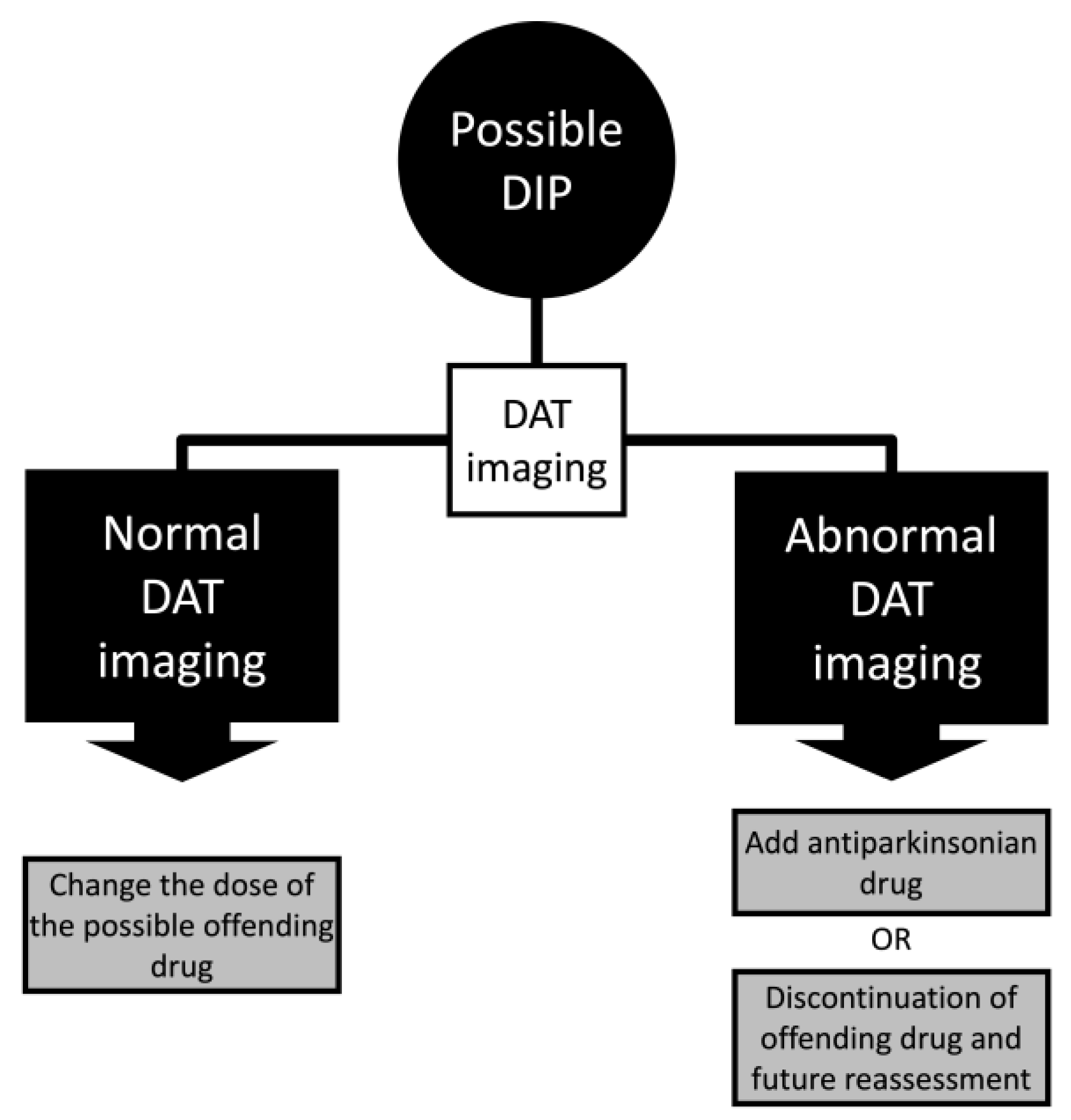

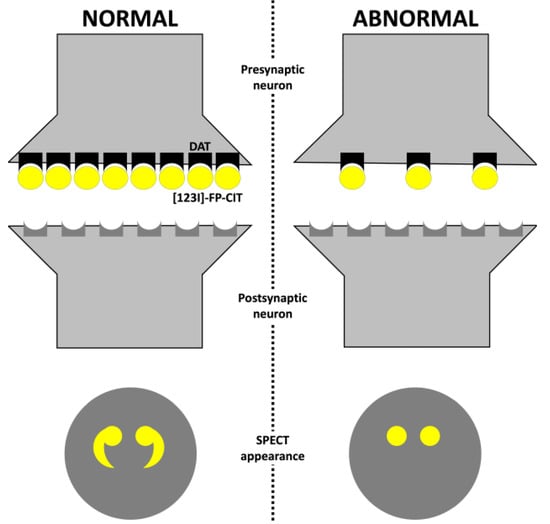

In a healthy individual, dopamine is released in the synaptic cleft, activating post-synaptic neurons. After, dopamine is removed from the synaptic cleft by dopamine transporter (DAT) reuptake. This sodium-dependent DAT is a membrane-spanning protein localized in the presynaptic membrane of neurons. Therefore, DAT imaging measures the functioning of dopaminergic terminals [23].

In a normal SPECT study, ioflupane (I123) binds to the DATs localized in the presynaptic neurons of the striatum (Figure 2). The SPECT appearance will be a comma- or crescent-shaped activity in the striatum region. The abbreviation for a normal DaTscan is SWEED, which stands for scan without evidence of dopaminergic deficit [24].

Figure 2.

Dopamine transporter radiotracer mechanism. Abbreviations: DAT, dopamine transporter; and SPECT, single-photon emission computed tomography.

In individuals with Parkinson’s disease, neuronal degeneration and loss of dopaminergic neurons can be observed in the striatum. Therefore, only a few DATs will be available in the striatal region for ioflupane to bind. The SPECT appearance will be abnormal with a period- or oval-shaped activity, which can also be reflected in a reduced intensity of one or both sides of the striatal region. In the early stages of Parkinson’s disease, a bilateral reduction in putaminal uptake with a more significant reduction in the putamen contralateral to the most affected limbs with normal uptake in the caudate region is observed [25]. The abbreviation for an abnormal DaTscan is SWIDD, which stands for scans with ipsilateral dopaminergic deficit. Some authors proposed a classification for SPECT imaging appearance of DAT based on the tracing uptake in the basal ganglia region (Table 2) [26,27].

Table 2.

Dopamine transporter uptake SPECT appearance classification.

Besides DAT, other mechanisms of the radioligands are related to dihydroxyphenylalanine (DOPA) decarboxylase and vesicular monoamine transporter type 2 (VMAT2). DOPA decarboxylase is a presynaptic radioligand associated with dopamine synthesis. On the other hand, the VMAT2 radioligand is another type of marker of dopaminergic terminals [28].

Some medications may alter tracer binding components due to their affinity to DAT or influencing the metabolism of radioligands or radionuclides. Thus, if possible, stopping them for at least five half-lives before the procedure is advised (Table 3). It is worth mentioning that there are only three absolute contraindications to dopamine transporter imaging: pregnancy, inability to co-operate with the procedure, and hypersensitivity to any component.

Table 3.

Recommendations regarding the influence of different agents in dopamine transporter imaging.

We reviewed the Pubmed database to find articles on radiotracers and drug-induced parkinsonism in humans. Table 4 summarizes the radioligands encountered in the literature (Table 4). The authors did not find studies of drug-induced parkinsonism with some radiotracers, such as [11C]-DOPA, [11C]-Raclopride, [18F]-Dihydrotetrabenazine, [123I]-Altropane, [11C]-Altropane, [11C]-WIN35428, [18F]-CFT, [11C]-PE2I, and [123I]-IPT (Table 5).

Table 4.

Radiotracers and drug-induced parkinsonism.

Table 5.

FreeText and MeSH search terms in the US National Library of Medicine.

2.3. [123I]-FP-CIT

[123I]-FP-CIT is one of the neuroimaging radiopharmaceutical drugs already approved by the US Food and Drug Administration and the European Medicines Agency (Table 6). [123I]-FP-CIT was first approved in Europe ten years before approval by the FDA. In this context, this radiotracer is the most studied form of DAT imaging in individuals with drug-induced parkinsonism.

Table 6.

Labeled indications for [123I]-FP-CIT.

There is a significant concern about the influence of aging on dopamine transporter neuroimaging. Autopsy studies revealed a significant reduction in neuromelanin-pigmented neurons in the substantia nigra and the concentration of striatal dopamine transporters with aging [48]. Thus, two large studies were performed to assess the influence of aging on dopamine transporter imaging with healthy subjects [49,50]. The aging effect found on dopamine transporters was independent of race. Moreover, aging did not affect the caudate-to-putamen ratio of DAT binding. Interestingly, some [123I]-FP-CIT studies reported higher striatal binding ratios in the female sex than in males. This effect was strongly associated with age, in which younger individuals had a more pronounced binding effect [51]. Therefore, the aging effect should not affect the diagnosis of parkinsonism secondary to drugs based on the putamen/caudate ratio found in DAT imaging.

Brigo et al. performed a meta-analysis to investigate the significance of neuroimaging to differentiate degenerative from non-degenerative parkinsonism. They found that [123I]-FP-CIT had a sensitivity and specificity of 85 and 80 percent in differentiating idiopathic PD from secondary parkinsonism associated with drugs and vascular conditions [52]. It is noteworthy that there are several limitations in assessing nuclear imaging with meta-analysis. The most significant are related to imaging processing and radiotracer differences, in which every set has a specific protocol and machine.

Table 7 describes the studies performed with [123I]-FP-CIT to differentiate individuals with Parkinson’s disease from parkinsonism secondary to drugs (Table 7).

Table 7.

[123I]-FP-CIT studies of individuals with drug-induced parkinsonism.

2.4. [123I]-β-CIT

123I-β-CIT is another cocaine derivative first synthesized by the chemist John L. Neumeyer [68]. It is approved by the EMA, but not by the US FDA. [123I]-FP-CIT and [123I]-β-CIT demonstrated a reduction in striatal uptake similarly in people with Parkinson’s disease. But the washed-out time from striatal tissue is up to twenty times faster for [123I]-FP-CIT than [123I]-β-CIT [69]. Moreover, the affinity to DATs was higher with [123I]-FP-CIT. The relatively increased affinity is probably associated with a faster rate of striatal washout and the establishment of transient equilibrium binding conditions at the DAT [70]. Therefore, [123I]-FP-CIT has faster kinetic properties and a relatively high affinity to DAT compared to [123I]-β-CIT.

Eerola et al. investigated the clinical role of [123I]-β-CIT in 195 individuals with movement disorders, of which 12 were diagnosed with drug-induced parkinsonism. The authors found lower [123I]-β-CIT ratios in the putamen, caudate nucleus, and whole striatum in patients with Parkinson’s disease compared to drug-induced parkinsonism. It is noteworthy that [123I]-β-CIT uptake correlated negatively with age (r = −0.39, p < 0.01) in parkinsonism secondary to drugs compared to Parkinson’s disease group [71].

Easterford et al. studied three patients that developed valproate-induced parkinsonism. The authors found no abnormality in the [123I]-β-CIT SPECT [72]. In another study, subjects with schizophrenia and long-term antipsychotic use did not present a difference in striatal dopamine transporter density compared to healthy subjects [73]. It is worth mentioning that these studies demonstrated a non-relationship between the dysfunction of striatal neurons and the development of abnormal movements with high doses or long-term use of offending agents.

2.5. [99mTc]-TRODAT-1

Technetium-99m is a tropane derivative, [99mTc]-TRODAT-1, which binds to the dopamine transporters. Compared to other dopamine transporter techniques, [99mTc]-TRODAT-1 has several advantages, such as the wide availability of Technetium-99m, lower cost, optimal energy for high-quality imaging, and prompt image visualization due to faster pharmacokinetics [74]. In individuals with Parkinson’s disease, compared to healthy individuals, there is a significant decrease in striatal uptake. It is noteworthy that there is no difference in the 99mTc uptake between early and late-onset Parkinson’s disease, so no correlation with disease progression can be assumed [75].

Fallahi et al. studied [99mTc]-TRODAT-1 in Parkinson’s disease and patients with essential tremor and parkinsonism secondary to drugs. They observed that subjects with non-degenerative forms of parkinsonism show significantly higher normalized basal ganglia uptake than individuals with Parkinson’s disease. The sensitivity and specificity of the technique to differentiate between parkinsonism secondary to drugs and Parkinson’s disease were 80% and 83.3%, respectively [76].

Fabiani et al. assessed 153 individuals with parkinsonism, in which [99mTc]-TRODAT-1 was performed. The authors found that, in the group of parkinsonism secondary to drugs, younger subjects showed the most significant reductions in radiotracer uptake. Moreover, the severity of nonmotor signs was associated with the uptake of the radiotracer. The accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity of [99mTc]-TRODAT-1 to differentiate Parkinson’s disease from drug-induced parkinsonism were 66.9%, 73.1%, and 44%, respectively. It is worth mentioning that these findings with an area under the curve of 0.767 should be highlighted because they are among the lowest already described for imaging methods to differentiate drug-induced from idiopathic Parkinson’s disease [77].

2.6. [18F]-DOPA

[18F]-DOPA measures the structural and biochemical integrity of dopaminergic neurons (Table 8). There is a limited number of studies with this radiopharmaceutical drug about drug-induced parkinsonism. A study assessed the efficacy of 18F-DOPA in 13 individuals with severe drug-induced parkinsonism. Putaminal uptake was normal in almost all participants and was predictive of improved clinical signs of parkinsonism. In patients with a reduced uptake, 75% had a progression to clinical parkinsonian symptoms despite the withdrawal of the dopamine receptor antagonist [78]. It is noteworthy that there are data in the literature suggesting that the chronic course of dopamine receptor antagonists may result in a compensatory increase of presynaptic dopamine metabolism, which may contradict the results of Burn et al. [79].

Table 8.

Labeled indications for [18F]-DOPA.

2.7. [18F]-AV-133

VMAT2 is responsible for storing monoamines, including dopamine, in presynaptic vesicles located in nerve endings, cell bodies, and dendrites. The reduction of this protein in the striatum reflects the loss of nigrostriatal terminals, in which the measurement of VMAT2 density has been studied to support the potential diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease [80]. Alexander et al. studied the influence of [18F]-AV-133 imaging in the changing clinical management of subjects with clinically uncertain parkinsonian syndrome. The authors found that three individuals with a previous DIP diagnosis had a post-scan DIP diagnosis. However, one individual with a previous neurodegenerative disorder diagnosis had a DIP diagnosis after the scan [81].

2.8. [18F]-FP-CIT

FP-CIT has been extensively studied with 123I radionuclide, but few studies with 18F exist. The attachment of 18F radionuclide to the FP-CIT ligand provides a radiotracer with high signal-to-noise ratios with low artifacts and fast kinetics. Hong et al. assessed 50 individuals with drug-induced parkinsonism, in which the participants were divided into full and partial recovery. Relative lower ligand uptake was observed in the ventral striatum, anterior putamen, and posterior putamen in the patients that achieved partial recovery compared to the complete recovery group [82].

Oh et al. used [18F]-FP-CIT and imaging software to discover the standardized uptake value ratios between patients with parkinsonism secondary to drugs and healthy individuals [83]. The analyzed volume-of-interest template revealed a decreased monoamine availability in the thalamus in individuals with drug-induced parkinsonism compared to healthy individuals. Interestingly, they did not find any difference in the concentrations of monoamines in other subregions (putamen, globus pallidus, and ventral striatum).

Shin et al. studied 76 patients with DIP that [18F]-FP-CIT was performed. The authors found that symmetric parkinsonism was more prevalent. Moreover, the duration of drug exposure before the onset of parkinsonism was shorter in the patients with normal imaging than those with abnormal imaging [84].

2.9. Neuroimaging and Receptors Occupancy

Some radiotracers related to dopaminergic metabolism are used to assess dopamine receptors’ occupancy by neuroleptic agents in humans. PET studies have shown that D2 receptor occupancy at above eighty percent invariably results in extrapyramidal side effects including, but not limited to, parkinsonian motor symptoms [85]. It is noteworthy that the knowledge of this association can lead to the development of medications with lower or specific dopaminergic occupancy, leading to fewer motor side effects.

Olanzapine was one of the medications whose doses were further adjusted with DAT imaging. Comparing olanzapine 5 mg and 20 mg a day showed an occupancy of 60 and 83% of the dopaminergic receptors, respectively, without differences in clinical efficacy at these doses [86]. Another medication that was already tested with dopamine receptors occupancy is risperidone. In this context, risperidone 4 mg showed an occupancy varying from 70% to 80% [87].

The graphical description of the dopamine receptors’ occupancy can be represented by hyperbole. In this way, increases in higher doses of dopamine blockers will not be beneficial because the patient will achieve an effective plateau [88]. Therefore, several studies with DAT imaging with lower doses of antipsychotics already showed a similar efficacy to higher antipsychotic doses with significantly fewer side effects.

3. [18F]-Fluorodeoxyglucose ([18F]-FDG) PET

[18F]-FDG is a radiotracer that can mark the tissue uptake of glucose, which is closely correlated with some metabolism pathways. Several studies already evaluated the use of [18F]-FDG in supporting the diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease, in which the specific pattern encountered is an increased uptake of the striatum, thalamus, motor cortex, and cerebellum. On the other hand, the temporoparietooccipital cortex is believed to have a lower uptake [89].

Kotomin et al. studied the metabolic brain imaging approach using the 18F-FDG PET and spatial covariance analysis to find possible factors that could predict drug-induced parkinsonism. They found that the expression of a Parkinson’s-disease-related pattern on 18F-FDG was commonly related to the development of parkinsonism secondary to drugs. However, this pattern was also observed in patients receiving antipsychotics without motor symptoms [90].

4. [123I]-MIBG Cardiac Imaging

[123I]-MIBG scintigraphy assesses the integrity of the cardiac sympathetic nerve terminals. Studies showed that this neuroimaging technique can be used to differentiate Parkinson’s disease from other forms of parkinsonism [91]. A limited number of studies assessing [123I]-MIBG scintigraphy in parkinsonism secondary to drugs have already been published in the literature.

Lee et al. evaluated 52 individuals with parkinsonism, of which 20 were diagnosed with drug-induced parkinsonism. Ten percent of the subjects with a drug-induced parkinsonism diagnosis showed a reduced uptake compared to patients with Parkinson’s disease. The two individuals with drug-induced parkinsonism and a reduced uptake also had no improvement in their motor symptoms with drug discontinuation. However, both patients significantly improved motor symptoms with the levodopa trial [92].

Lee et al. performed a second study with cross-cultural smell identification (CCSI) testing in 54 individuals with parkinsonism, of which 15 were diagnosed with drug-induced parkinsonism. One of the participants had low CCSI scores and a reduced uptake of [123I]-MIBG, which can suggest that olfactory tests may help distinguish between parkinsonism secondary to drugs and subclinical Parkinson’s disease. It is noteworthy that the CCSI test can be performed quickly in the outpatient clinic and is inexpensive compared to scintigraphy [93].

Kim et al. studied the combination of [123I]-MIBG and [123I]-FP-CIT SPECT in 36 individuals with parkinsonism, of which 20 had a diagnosis of drug-induced parkinsonism. In this study, 80% of the individuals with drug-induced parkinsonism had normal cardiac imaging and DAT imaging studies. Interestingly, two individuals presented with normal [123I]-FP-CIT and decreased [123I]-MIBG uptakes. After two years, these individuals had worsened parkinsonian symptoms. A second imaging sequence showed a reduced uptake of [123I]-FP-CIT and [123I]-MIBG. Therefore, these findings suggest cardiac abnormalities are found before striatal region lesions. In this way, it is possible that those patients with probable drug-induced parkinsonism and normal DAT scans with less improvement after drug discontinuation will benefit significantly from cardiac imaging [94].

Shafie et al. studied 44 patients with parkinsonism secondary to drugs and 32 patients with idiopathic Parkinson’s disease. The authors found that the difference [123I]-MIBG uptake between the Parkinson’s disease and drug-induced parkinsonism groups was significant. Moreover, Shafie et al. reported that [123I]-MIBG scans could be used to determine the prognosis of people with parkinsonism secondary to drugs. The subjects with drug-induced parkinsonism that did not improve motor symptoms after offending drug discontinuation had a low heart-to-mediastinum ratio [95].

5. Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)—The Swallowtail Appearance

Nigrosomes are small clusters of dopaminergic cells within the healthy substantia nigra. They can have a hypersignal in the axial section, with either a linear or comma appearance. They are bordered anteriorly, laterally, and medially by a low-intensity signal, giving it a swallow-tailed appearance. A loss of the normal swallowtail appearance of the susceptibility signal pattern in the substantia nigra on axial imaging is one of the diagnostic signs for Parkinson’s disease [96].

Sung et al. studied 20 individuals with drug-induced parkinsonism and 29 with Parkinson’s disease. The individuals were first assessed with [18F]-FP-CIT imaging after nigrosome-1 3T imaging was evaluated. Then, 85% of the patients with parkinsonism secondary to drugs were interpreted as normal 3T imaging findings, in which the sensitivity was 100%, specificity 85%, and accuracy 93.9% [97].

Studies with an ultra-high-field MRI (7T) showed significant sensitivity and specificity for diagnosing Parkinson’s disease based on the loss of the swallowtail appearance [98]. Therefore, future investigations with high-quality neuroimaging could be a promising field for supporting the diagnosis of non-degenerative causes of parkinsonism, such as parkinsonism secondary to drugs.

6. Transcranial Ultrasound

B-mode transcranial ultrasonography was already studied to support the diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease. This imaging method, when compared to other techniques, has significant advantages, such as relatively low costs, broad availability, and a noninvasive approach. The characteristic finding in patients with Parkinson’s disease is an increased echogenicity of the mesencephalic substantia nigra region, which is probably related to iron deposition [99]. The presence of this sign is highly specific to the diagnosis of a degenerative form of parkinsonism. Nevertheless, the sensitivity depends on the exact cut-off value of the substantia nigra area used and the type of ultrasound machine [100].

Bouwmans et al. assessed 196 individuals with parkinsonism of unclear etiology. After two years of follow-up, seven individuals were diagnosed with drug-induced parkinsonism. All the individuals were evaluated with [123I]-FP-CIT and B-mode transcranial ultrasonography. Ultrasonography accurately identified drug-induced parkinsonism in 86% of the subjects [101].

Olivares Romero et al.’s study enrolled 20 subjects diagnosed with possible drug-induced parkinsonism in which the offending agent was discontinued. The authors found a sensitivity of 80% and a negative predictive value of 87.5% with the evaluation of echogenicity in the substantia nigra and the lentiform nucleus regions [102].

Oh et al. studied the significance of early transcranial ultrasound in diagnosing drug-induced parkinsonism. They found pure drug-induced parkinsonism has different echogenicity patterns than unmasked Parkinson’s disease. The substantia nigra hyperechogenicity in patients with unmasked Parkinson’s disease showed a sensitivity of 75% and a specificity of 91.1%. Therefore, early transcranial ultrasonography findings may be useful in predicting unmasked Parkinson’s disease in individuals presenting with possible parkinsonism secondary to drugs [103].

7. Optical Coherence Tomography

Patients with Parkinson’s disease commonly present visual symptoms, especially perceptual disturbances such as impairment in stereopsis, visual illusions, and visual hallucinations. Patients with Parkinson’s disease have a decreased average capillary retinal nerve fiber layer in every quadrant [104]. Moreover, Jimenez et al. proposed an equation to determine the Parkinson’s disease progression based on the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) total score and the retinal nerve fiber layer thickness measured by optical coherence tomography [105].

Suh et al. assessed 97 individuals with Parkinson’s disease and 27 with parkinsonism secondary to drugs using optical coherence tomography and [18F] N-(3-fluoropropyl)-2b-carbon ethoxy-3b-(4-iodophenyl) nortropane (FP-CIT). They compared the two groups’ peripapillary retinal nerve fiber layer and macular retinal thickness. There were no significant differences in peripapillary and macular retinal thickness values [106]. Suh et al.’s study is important because it showed that, in the early stages of drug-induced parkinsonism, there is no benefit in measuring these optic parameters to differ from early Parkinson’s disease.

8. Expert Recommendations

The time between “drug discontinuation” and “neuroimaging” in drug-induced parkinsonism is one of the main concerns in clinical practice (Table 9). Some authors state that neuroimaging should be carried out within the first month of the drug withdrawal. Others propose that neuroimaging should only be requested for patients with partial or no improvement of motor symptoms after six months of discontinuing the offending drug.

Table 9.

Comparison among different neuroimaging techniques for the differentiation between PD and DIP.

The best approach may be to search for systematic studies in the literature regarding specific drugs or classes of drugs and their association with parkinsonism, for example, an individual presenting with parkinsonism after flunarizine therapy. Rissardo et al. described a systematic review of cinnarizine and flunarizine associated with movement disorders [107]. The authors found that 94.85% of the individuals who developed cinnarizine- or flunarizine-induced parkinsonism had a complete recovery within six months of drug discontinuation. Therefore, if the individual with parkinsonism does not show improvement within the first six months of drug discontinuation, neuroimaging should be requested to evaluate the dopaminergic pathway in the striatal region.

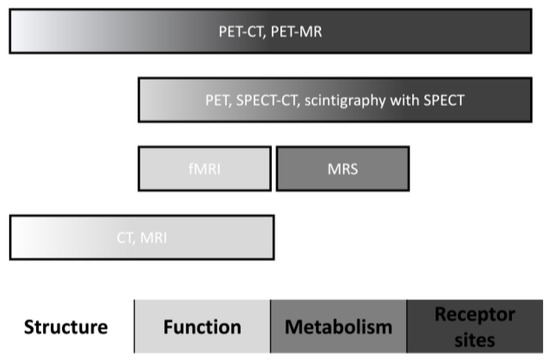

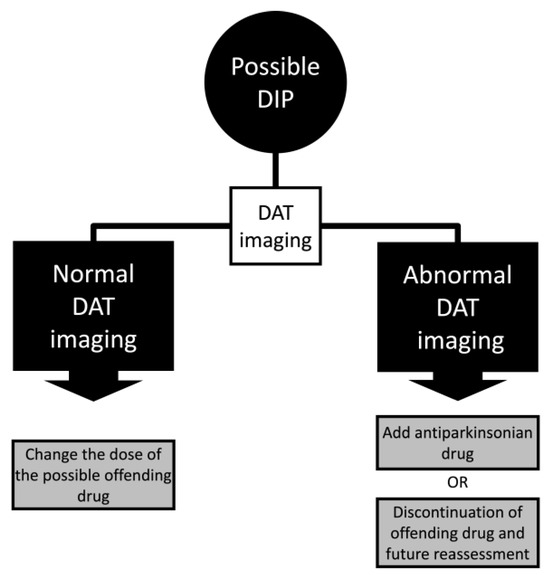

Another important clue for using DAT imaging is that in cases where the drug possibly causing abnormal motor symptoms cannot be discontinued. One possible approach could be to use DAT imaging to titrate the offending drug or include antiparkinsonian drugs in the patient’s therapy (Figure 3). Moreover, the offending drug discontinuation with a further reassessment in patients with abnormal DAT imaging and a low probability of developing Parkinson’s disease should be carried out. One possible explanation in these cases is the subclinical drug-exacerbated parkinsonism, in which the individual develops parkinsonism with a symmetrical abnormality in DAT and neurologic examination after a short term of the medication, mainly dopamine-blocking agents.

Figure 3.

Algorithm of drug-induced parkinsonism (DIP) management with dopamine transporter (DAT) imaging.

There are several limitations in the present study. First, most studies included did not specifically assess only parkinsonism secondary to drugs. In their analysis, the authors included patients with drug-induced parkinsonism with vascular parkinsonism and essential tremor to provide larger samples. Second, there is a significantly low number of studies evaluating the use of neuroimaging techniques to distinguish between neurodegenerative and drug-induced parkinsonism. It is noteworthy that many studies were performed by the same groups, which could lead to the repetition of selective bias. Third, a systematic literature search was only performed to describe the radiotracers.

9. Future Studies

The literature on neuroimaging in drug-induced movement disorders is scarce. There are only a few studies assessing different types of radiotracers. After these initial studies, head-to-head trials comparing the different radiotracers are needed to evaluate sensitivity and specificity. Future studies should develop protocols for performing neuroimaging in individuals with drug-induced parkinsonism. The best time to request neuroimaging and the influence of different medications with washing-out periods should be studied.

Clinical symptoms associated with invasive and non-invasive neuroimaging methods must be studied. These results can provide a significant change in clinical practice, leading to the development of calculators and scores that may help the clinician to provide prognosis and specific management. Another approach for neuroimaging in drug-induced parkinsonism is the dual imaging algorithm, which involves performing imaging in the central and peripheral nervous system. This algorithm has been used in the last decade to differentiate Parkinson’s disease from other forms of parkinsonism. It is worth mentioning that individuals with drug-induced parkinsonism will present normal results in both studies.

10. Conclusions

The neuroimaging techniques already studied with drug-induced parkinsonism are dopaminergic radiotracers, [18F]-FDG, [123I]-MIBG cardiac scintigraphy, structural MRI, transcranial ultrasound, and optical coherence tomography. The procedure with the highest number of publications is dopamine transporter imaging. [123I]-FP-CIT is the most frequently performed and studied imaging agent with drug-induced parkinsonism. There are significant differences between the radiotracers, which future studies should assess. Neuroimaging in drug-induced parkinsonism might improve diagnosis, prognosis, and appropriate medication use, translating into better patient care with favorable outcomes.

Author Contributions

J.P.R. and A.L.F.C. conceived and designed the literature review methodology. J.P.R. and A.L.F.C. extracted and collected the relevant information and drafted the manuscript. A.L.F.C. supervised the article selection and reviewed and edited the manuscript. J.P.R. and A.L.F.C. reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Baizabal-Carvallo, J.F.; Morgan, J.C. Drug-Induced Tremor, Clinical Features, Diagnostic Approach and Management. J. Neurol. Sci. 2022, 435, 120192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rissardo, J.P.; Vora, N.; Mathew, B.; Kashyap, V.; Muhammad, S.; Fornari Caprara, A.L. Overview of Movement Disorders Secondary to Drugs. Clin. Pract. 2023, 13, 959–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esper, C.D.; Factor, S.A. Failure of Recognition of Drug-Induced Parkinsonism in the Elderly. Mov. Disord. 2008, 23, 401–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Germay, S.; Montastruc, F.; Carvajal, A.; Lapeyre-Mestre, M.; Montastruc, J.-L. Drug-Induced Parkinsonism: Revisiting the Epidemiology Using the WHO Pharmacovigilance Database. Park. Relat. Disord. 2020, 70, 55–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feldman, M.; Marmol, S.; Margolesky, J. Updated Perspectives on the Management of Drug-Induced Parkinsonism (DIP): Insights from the Clinic. Ther. Clin. Risk Manag. 2022, 18, 1129–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rissardo, J.P.; Caprara, A.L.F. Predictors of Drug-Induced Parkinsonism. APIK J. Intern. Med. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rissardo, J.P.; Fornari Caprara, A.L. Lamotrigine-Associated Movement Disorder: A Literature Review. Neurol. India 2021, 69, 1524–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rissardo, J.P.; Caprara, A.L.F. Fluoroquinolone-Associated Movement Disorder: A Literature Review. Medicines 2023, 10, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardie, R.J.; Lees, A.J. Neuroleptic-Induced Parkinson’s Syndrome: Clinical Features and Results of Treatment with Levodopa. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 1988, 51, 850–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitri, A.; Hurd, Y.L.; Wyatt, R.J.; Deutsch, S.I. Molecular, Functional and Biochemical Characteristics of the Dopamine Transporter: Regional Differences and Clinical Relevance. Clin. Neuropharmacol. 1994, 17, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaya, E.K.; Scheffel, U.; Dannals, R.F.; Ricaurte, G.A.; Carroll, F.I.; Wagner, H.N.J.; Kuhar, M.J.; Wong, D.F. In Vivo Imaging of Dopamine Reuptake Sites in the Primate Brain Using Single Photon Emission Computed Tomography (SPECT) and Iodine-123 Labeled RTI-55. Synapse 1992, 10, 169–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flace, P.; Livrea, P.; Basile, G.A.; Galletta, D.; Bizzoca, A.; Gennarini, G.; Bertino, S.; Branca, J.J.V.; Gulisano, M.; Bianconi, S.; et al. The Cerebellar Dopaminergic System. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 650614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brooks, D.J. Molecular Imaging of Dopamine Transporters. Ageing Res. Rev. 2016, 30, 114–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benamer, H.T.S.; Patterson, J.; Grosset, D.G.; Booij, J.; de Bruin, K.; van Royen, E.; Speelman, J.D.; Horstink, M.H.I.M.; Sips, H.J.W.A.; Dierckx, R.A.; et al. Accurate Differentiation of Parkinsonism and Essential Tremor Using Visual Assessment of [(123) I]-FP-CIT SPECT Imaging: The [(123) I]-FP-CIT Study Group. Mov. Disord. 2000, 15, 503–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Catafau, A.M.; Tolosa, E. Impact of Dopamine Transporter SPECT Using 123I-Ioflupane on Diagnosis and Management of Patients with Clinically Uncertain Parkinsonian Syndromes. Mov. Disord. 2004, 19, 1175–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jennings, D.L.; Seibyl, J.P.; Oakes, D.; Eberly, S.; Murphy, J.; Marek, K. (123I) Beta-CIT and Single-Photon Emission Computed Tomographic Imaging vs Clinical Evaluation in Parkinsonian Syndrome: Unmasking an Early Diagnosis. Arch. Neurol. 2004, 61, 1224–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, V.L.; Reininger, C.B.; Marquardt, M.; Patterson, J.; Hadley, D.M.; Oertel, W.H.; Benamer, H.T.S.; Kemp, P.; Burn, D.; Tolosa, E.; et al. Parkinson’s Disease Is Overdiagnosed Clinically at Baseline in Diagnostically Uncertain Cases: A 3-Year European Multicenter Study with Repeat [123I]FP-CIT SPECT. Mov. Disord. 2009, 24, 500–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, F.I.; Lewin, A.H.; Boja, J.W.; Kuhar, M.J. Cocaine Receptor: Biochemical Characterization and Structure-Activity Relationships of Cocaine Analogues at the Dopamine Transporter. J. Med. Chem. 1992, 35, 969–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi Gharibkandi, N.; Hosseinimehr, S.J. Radiotracers for Imaging of Parkinson’s Disease. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 166, 75–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaquero, J.J.; Kinahan, P. Positron Emission Tomography: Current Challenges and Opportunities for Technological Advances in Clinical and Preclinical Imaging Systems. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2015, 17, 385–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ba, F.; Martin, W.R.W. Dopamine Transporter Imaging as a Diagnostic Tool for Parkinsonism and Related Disorders in Clinical Practice. Park. Relat. Disord. 2015, 21, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seifert, K.D.; Wiener, J.I. The Impact of DaTscan on the Diagnosis and Management of Movement Disorders: A Retrospective Study. Am. J. Neurodegener. Dis. 2013, 2, 29–34. [Google Scholar]

- Latif, S.; Jahangeer, M.; Maknoon Razia, D.; Ashiq, M.; Ghaffar, A.; Akram, M.; El Allam, A.; Bouyahya, A.; Garipova, L.; Ali Shariati, M.; et al. Dopamine in Parkinson’s Disease. Clin. Chim. Acta 2021, 522, 114–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kägi, G.; Bhatia, K.P.; Tolosa, E. The Role of DAT-SPECT in Movement Disorders. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2010, 81, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filippi, L.; Manni, C.; Pierantozzi, M.; Brusa, L.; Danieli, R.; Stanzione, P.; Schillaci, O. 123I-FP-CIT Semi-Quantitative SPECT Detects Preclinical Bilateral Dopaminergic Deficit in Early Parkinson’s Disease with Unilateral Symptoms. Nucl. Med. Commun. 2005, 26, 421–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharjee, S.; Shankar, P.V.; Elkider, M. Dopamine Transporter Single-Photon Emission Computed Tomography Brain Scan: A Reliable Way to Distinguish between Degenerative and Drug-Induced Parkinsonism. Indian J. Nucl. Med. 2016, 31, 249–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manoharan, P.; Jamieson, S.; Bury, R.F. Initial Clinical Experience with [123I]Ioflupane Scintigraphy in Movement Disorders. Clin. Radiol. 2007, 62, 463–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleppe, R.; Waheed, Q.; Ruoff, P. DOPA Homeostasis by Dopamine: A Control-Theoretic View. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 12862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booij, J.; Kemp, P. Dopamine Transporter Imaging with [(123)I]FP-CIT SPECT: Potential Effects of Drugs. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2008, 35, 424–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkow, N.D.; Chang, L.; Wang, G.J.; Fowler, J.S.; Leonido-Yee, M.; Franceschi, D.; Sedler, M.J.; Gatley, S.J.; Hitzemann, R.; Ding, Y.S.; et al. Association of Dopamine Transporter Reduction with Psychomotor Impairment in Methamphetamine Abusers. Am. J. Psychiatry 2001, 158, 377–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiffer, W.K.; Logan, J.; Dewey, S.L. Positron Emission Tomography Studies of Potential Mechanisms Underlying Phencyclidine-Induced Alterations in Striatal Dopamine. Neuropsychopharmacology 2003, 28, 2192–2198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ukairo, O.T.; Bondi, C.D.; Newman, A.H.; Kulkarni, S.S.; Kozikowski, A.P.; Pan, S.; Surratt, C.K. Recognition of Benztropine by the Dopamine Transporter (DAT) Differs from That of the Classical Dopamine Uptake Inhibitors Cocaine, Methylphenidate, and Mazindol as a Function of a DAT Transmembrane 1 Aspartic Acid Residue. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2005, 314, 575–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kilbourn, M.R.; Kemmerer, E.S.; Desmond, T.J.; Sherman, P.S.; Frey, K.A. Differential Effects of Scopolamine on in Vivo Binding of Dopamine Transporter and Vesicular Monoamine Transporter Radioligands in Rat Brain. Exp. Neurol. 2004, 188, 387–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Argyelán, M.; Szabó, Z.; Kanyó, B.; Tanács, A.; Kovács, Z.; Janka, Z.; Pávics, L. Dopamine Transporter Availability in Medication Free and in Bupropion Treated Depression: A 99mTc-TRODAT-1 SPECT Study. J. Affect. Disord. 2005, 89, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volkow, N.D.; Wang, G.-J.; Fowler, J.S.; Learned-Coughlin, S.; Yang, J.; Logan, J.; Schlyer, D.; Gatley, J.S.; Wong, C.; Zhu, W.; et al. The Slow and Long-Lasting Blockade of Dopamine Transporters in Human Brain Induced by the New Antidepressant Drug Radafaxine Predict Poor Reinforcing Effects. Biol. Psychiatry 2005, 57, 640–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kugaya, A.; Seneca, N.M.; Snyder, P.J.; Williams, S.A.; Malison, R.T.; Baldwin, R.M.; Seibyl, J.P.; Innis, R.B. Changes in Human in Vivo Serotonin and Dopamine Transporter Availabilities during Chronic Antidepressant Administration. Neuropsychopharmacology 2003, 28, 413–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, Y.; Gibbs, M.A.; Marek, G.J.; Stiger, T.; Burstein, A.H.; Marek, K.; Seibyl, J.P.; Rogers, J.F. Displacement of Serotonin and Dopamine Transporters by Venlafaxine Extended Release Capsule at Steady State: A [123I]2beta-Carbomethoxy-3beta-(4-Iodophenyl)-Tropane Single Photon Emission Computed Tomography Imaging Study. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2007, 27, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schillaci, O.; Pierantozzi, M.; Filippi, L.; Manni, C.; Brusa, L.; Danieli, R.; Bernardi, G.; Simonetti, G.; Stanzione, P. The Effect of Levodopa Therapy on Dopamine Transporter SPECT Imaging with( 123)I-FP-CIT in Patients with Parkinson’s Disease. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2005, 32, 1452–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahlskog, J.E.; Uitti, R.J.; O’Connor, M.K.; Maraganore, D.M.; Matsumoto, J.Y.; Stark, K.F.; Turk, M.F.; Burnett, O.L. The Effect of Dopamine Agonist Therapy on Dopamine Transporter Imaging in Parkinson’s Disease. Mov. Disord. 1999, 14, 940–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innis, R.B.; Marek, K.L.; Sheff, K.; Zoghbi, S.; Castronuovo, J.; Feigin, A.; Seibyl, J.P. Effect of Treatment with L-Dopa/Carbidopa or L-Selegiline on Striatal Dopamine Transporter SPECT Imaging with [123I]Beta-CIT. Mov. Disord. 1999, 14, 436–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, J.-P.; Colloby, S.J.; McKeith, I.G.; Burn, D.J.; Williams, D.; Patterson, J.; O’Brien, J.T. Cholinesterase Inhibitor Use Does Not Significantly Influence the Ability of 123I-FP-CIT Imaging to Distinguish Alzheimer’s Disease from Dementia with Lewy Bodies. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2007, 78, 1069–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Volkow, N.D.; Wang, G.J.; Fischman, M.W.; Foltin, R.W.; Fowler, J.S.; Abumrad, N.N.; Vitkun, S.; Logan, J.; Gatley, S.J.; Pappas, N.; et al. Relationship between Subjective Effects of Cocaine and Dopamine Transporter Occupancy. Nature 1997, 386, 827–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Best, S.E.; Sarrel, P.M.; Malison, R.T.; Laruelle, M.; Zoghbi, S.S.; Baldwin, R.M.; Seibyl, J.P.; Innis, R.B.; van Dyck, C.H. Striatal Dopamine Transporter Availability with [123I]Beta-CIT SPECT Is Unrelated to Gender or Menstrual Cycle. Psychopharmacology 2005, 183, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madras, B.K.; Xie, Z.; Lin, Z.; Jassen, A.; Panas, H.; Lynch, L.; Johnson, R.; Livni, E.; Spencer, T.J.; Bonab, A.A.; et al. Modafinil Occupies Dopamine and Norepinephrine Transporters in Vivo and Modulates the Transporters and Trace Amine Activity in Vitro. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2006, 319, 561–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateos, J.J.; Lomeña, F.; Parellada, E.; Mireia, F.; Fernandez-Egea, E.; Pavia, J.; Prats, A.; Pons, F.; Bernardo, M. Lower Striatal Dopamine Transporter Binding in Neuroleptic-Naive Schizophrenic Patients Is Not Related to Antipsychotic Treatment but It Suggests an Illness Trait. Psychopharmacology 2007, 191, 805–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergström, K.A.; Jolkkonen, J.; Kuikka, J.T.; Akerman, K.K.; Viinamäki, H.; Airaksinen, O.; Länsimies, E.; Tiihonen, J. Fentanyl Decreases Beta-CIT Binding to the Dopamine Transporter. Synapse 1998, 29, 413–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaaijer, E.R.; van Dijk, L.; de Bruin, K.; Goudriaan, A.E.; Lammers, L.A.; Koeter, M.W.J.; van den Brink, W.; Booij, J. Effect of Extended-Release Naltrexone on Striatal Dopamine Transporter Availability, Depression and Anhedonia in Heroin-Dependent Patients. Psychopharmacology 2015, 232, 2597–2607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, K.M. The Effects of Aging on Substantia Nigra Dopamine Neurons. J. Neurosci. 2014, 34, 15133–15134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozley, P.D.; Acton, P.D.; Barraclough, E.D.; Plössl, K.; Gur, R.C.; Alavi, A.; Mathur, A.; Saffer, J.; Kung, H.F. Effects of Age on Dopamine Transporters in Healthy Humans. J. Nucl. Med. 1999, 40, 1812–1817. [Google Scholar]

- Lavalaye, J.; Booij, J.; Reneman, L.; Habraken, J.B.A.; van Royen, E.A. Effect of Age and Gender on Dopamine Transporter Imaging with [123I]FP-CIT SPET in Healthy Volunteers. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. 2000, 27, 867–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaasinen, V.; Joutsa, J.; Noponen, T.; Johansson, J.; Seppänen, M. Effects of Aging and Gender on Striatal and Extrastriatal [123I]FP-CIT Binding in Parkinson’s Disease. Neurobiol. Aging 2015, 36, 1757–1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brigo, F.; Matinella, A.; Erro, R.; Tinazzi, M. [123I]FP-CIT SPECT (DaTSCAN) May Be a Useful Tool to Differentiate between Parkinson’s Disease and Vascular or Drug-Induced Parkinsonisms: A Meta-Analysis. Eur. J. Neurol. 2014, 21, 1369-e90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booij, J.; Speelman, J.D.; Horstink, M.W.; Wolters, E.C. The Clinical Benefit of Imaging Striatal Dopamine Transporters with [123I]FP-CIT SPET in Differentiating Patients with Presynaptic Parkinsonism from Those with Other Forms of Parkinsonism. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. 2001, 28, 266–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorberboym, M.; Treves, T.A.; Melamed, E.; Lampl, Y.; Hellmann, M.; Djaldetti, R. [123I]-FP/CIT SPECT Imaging for Distinguishing Drug-Induced Parkinsonism from Parkinson’s Disease. Mov. Disord. 2006, 21, 510–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlaar, A.M.M.; de Nijs, T.; Kessels, A.G.H.; Vreeling, F.W.; Winogrodzka, A.; Mess, W.H.; Tromp, S.C.; van Kroonenburgh, M.J.P.G.; Weber, W.E.J. Diagnostic Value of 123I-Ioflupane and 123I-Iodobenzamide SPECT Scans in 248 Patients with Parkinsonian Syndromes. Eur. Neurol. 2008, 59, 258–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tinazzi, M.; Ottaviani, S.; Isaias, I.U.; Pasquin, I.; Steinmayr, M.; Vampini, C.; Pilleri, M.; Moretto, G.; Fiaschi, A.; Smania, N.; et al. [123I]FP-CIT SPET Imaging in Drug-Induced Parkinsonism. Mov. Disord. 2008, 23, 1825–1829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinazzi, M.; Antonini, A.; Bovi, T.; Pasquin, I.; Steinmayr, M.; Moretto, G.; Fiaschi, A.; Ottaviani, S. Clinical and [123I]FP-CIT SPET Imaging Follow-up in Patients with Drug-Induced Parkinsonism. J. Neurol. 2009, 256, 910–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Corrales, F.J.; Sanz-Viedma, S.; Garcia-Solis, D.; Escobar-Delgado, T.; Mir, P. Clinical Features and 123I-FP-CIT SPECT Imaging in Drug-Induced Parkinsonism and Parkinson’s Disease. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2010, 37, 556–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hambÿe, A.-S.; Vervaet, A.; Dethy, S. FP-CIT SPECT in Clinically Inconclusive Parkinsonian Syndrome during Amiodarone Treatment: A Study with Follow-Up. Nucl. Med. Commun. 2010, 31, 583–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuberas-Borrós, G.; Lorenzo-Bosquet, C.; Aguadé-Bruix, S.; Hernández-Vara, J.; Pifarré-Montaner, P.; Miquel, F.; Álvarez-Sabin, J.; Castell-Conesa, J. Quantitative Evaluation of Striatal I-123-FP-CIT Uptake in Essential Tremor and Parkinsonism. Clin. Nucl. Med. 2011, 36, 991–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinazzi, M.; Cipriani, A.; Matinella, A.; Cannas, A.; Solla, P.; Nicoletti, A.; Zappia, M.; Morgante, L.; Morgante, F.; Pacchetti, C.; et al. [123I]FP-CIT Single Photon Emission Computed Tomography Findings in Drug-Induced Parkinsonism. Schizophr. Res. 2012, 139, 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olivares Romero, J.; Arjona Padillo, A. Diagnostic accuracy of 123 I-FP-CIT SPECT in diagnosing drug-induced parkinsonism: A prospective study. Neurologia 2013, 28, 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tinazzi, M.; Morgante, F.; Matinella, A.; Bovi, T.; Cannas, A.; Solla, P.; Marrosu, F.; Nicoletti, A.; Zappia, M.; Luca, A.; et al. Imaging of the Dopamine Transporter Predicts Pattern of Disease Progression and Response to Levodopa in Patients with Schizophrenia and Parkinsonism: A 2-Year Follow-up Multicenter Study. Schizophr. Res. 2014, 152, 344–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morley, J.F.; Cheng, G.; Dubroff, J.G.; Wood, S.; Wilkinson, J.R.; Duda, J.E. Olfactory Impairment Predicts Underlying Dopaminergic Deficit in Presumed Drug-Induced Parkinsonism. Mov. Disord. Clin. Pract. 2017, 4, 603–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tachibana, K.; HIrata, Y.; Katoh, N.; Ishikawa, H.; Shimada, T.; Shindo, A.; Matsuura, K.; Asahi, M.; Satoh, M.; Ii, Y.; et al. Differentiation of Drug-Induced Parkinsonism and PD.; Utility of 123I-FP-CIT SPECT(DaTscan). J. Neurol. Sci. 2017, 381, 954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajos, A.; Dąbrowski, J.; Bieńkiewicz, M.; Płachcińska, A.; Kuśmierek, J.; Bogucki, A. The Symptoms Asymmetry of Drug-Induced Parkinsonism Is Not Related to Nigrostriatal Cell Degeneration: A SPECT-DaTSCAN Study. Neurol. Neurochir. Pol. 2019, 53, 311–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aamodt, W.W.; Dubroff, J.G.; Cheng, G.; Taylor, B.; Wood, S.; Duda, J.E.; Morley, J.F. Gait Abnormalities and Non-Motor Symptoms Predict Abnormal Dopaminergic Imaging in Presumed Drug-Induced Parkinsonism. NPJ Park. Dis. 2022, 8, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumeyer, J.L.; Wang, S.; Gao, Y.; Milius, R.A.; Kula, N.S.; Campbell, A.; Baldessarini, R.J.; Zea-Ponce, Y.; Baldwin, R.M.; Innis, R.B. N-Omega-Fluoroalkyl Analogs of (1R)-2 Beta-Carbomethoxy-3 Beta-(4-Iodophenyl)-Tropane (Beta-CIT): Radiotracers for Positron Emission Tomography and Single Photon Emission Computed Tomography Imaging of Dopamine Transporters. J. Med. Chem. 1994, 37, 1558–1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abi-Dargham, A.; Gandelman, M.S.; DeErausquin, G.A.; Zea-Ponce, Y.; Zoghbi, S.S.; Baldwin, R.M.; Laruelle, M.; Charney, D.S.; Hoffer, P.B.; Neumeyer, J.L.; et al. SPECT Imaging of Dopamine Transporters in Human Brain with Iodine-123-Fluoroalkyl Analogs of Beta-CIT. J. Nucl. Med. 1996, 37, 1129–1133. [Google Scholar]

- Seibyl, J.P.; Marek, K.; Sheff, K.; Zoghbi, S.; Baldwin, R.M.; Charney, D.S.; van Dyck, C.H.; Innis, R.B. Iodine-123-Beta-CIT and Iodine-123-FPCIT SPECT Measurement of Dopamine Transporters in Healthy Subjects and Parkinson’s Patients. J. Nucl. Med. 1998, 39, 1500–1508. [Google Scholar]

- Eerola, J.; Tienari, P.J.; Kaakkola, S.; Nikkinen, P.; Launes, J. How Useful Is [123I]Beta-CIT SPECT in Clinical Practice? J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2005, 76, 1211–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Easterford, K.; Clough, P.; Kellett, M.; Fallon, K.; Duncan, S. Reversible Parkinsonism with Normal Beta-CIT-SPECT in Patients Exposed to Sodium Valproate. Neurology 2004, 62, 1435–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laruelle, M.; Abi-Dargham, A.; van Dyck, C.H.; Gil, R.; D’Souza, C.D.; Erdos, J.; McCance, E.; Rosenblatt, W.; Fingado, C.; Zoghbi, S.S.; et al. Single Photon Emission Computerized Tomography Imaging of Amphetamine-Induced Dopamine Release in Drug-Free Schizophrenic Subjects. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1996, 93, 9235–9240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolzati, C.; Dolmella, A. Nitrido Technetium-99 m Core in Radiopharmaceutical Applications: Four Decades of Research. Inorganics 2020, 8, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasannezhad, P.; Juibary, A.G.; Sadri, K.; Sadeghi, R.; Sabour, M.; Kakhki, V.R.D.; Alizadeh, H. (99m)Tc-TRODAT-1 SPECT Imaging in Early and Late Onset Parkinson’s Disease. Asia Ocean. J. Nucl. Med. Biol. 2017, 5, 114–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallahi, B.; Esmaeili, A.; Beiki, D.; Oveisgharan, S.; Noorollahi-Moghaddam, H.; Erfani, M.; Tafakhori, A.; Rohani, M.; Fard-Esfahani, A.; Emami-Ardekani, A.; et al. Evaluation of (99m)Tc-TRODAT-1 SPECT in the Diagnosis of Parkinson’s Disease versus Other Progressive Movement Disorders. Ann. Nucl. Med. 2016, 30, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabiani, G.; Camargo, C.H.F.; Filho, R.M.; Froehner, G.S.; Teive, H.A.G. Evaluation of Brain SPECT with (99m)Tc-TRODAT-1 in the Differential Diagnosis of Parkinsonism. Parkinsons Dis. 2022, 2022, 1746540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burn, D.J.; Brooks, D.J. Nigral Dysfunction in Drug-Induced Parkinsonism: An 18F-Dopa PET Study. Neurology 1993, 43, 552–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dackis, C.A.; Gold, M.S. New Concepts in Cocaine Addiction: The Dopamine Depletion Hypothesis. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 1985, 9, 469–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulvihill, K.G. Presynaptic Regulation of Dopamine Release: Role of the DAT and VMAT2 Transporters. Neurochem. Int. 2019, 122, 94–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, P.K.; Lie, Y.; Jones, G.; Sivaratnam, C.; Bozinvski, S.; Mulligan, R.S.; Young, K.; Villemagne, V.L.; Rowe, C.C. Management Impact of Imaging Brain Vesicular Monoamine Transporter Type 2 in Clinically Uncertain Parkinsonian Syndrome with (18)F-AV133 and PET. J. Nucl. Med. 2017, 58, 1815–1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, J.Y.; Sunwoo, M.K.; Oh, J.S.; Kim, J.S.; Sohn, Y.H.; Lee, P.H. Persistent Drug-Induced Parkinsonism in Patients with Normal Dopamine Transporter Imaging. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0157410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, Y.-S.; Yoo, S.-W.; Lyoo, C.H.; Kim, J.-S. Decreased Thalamic Monoamine Availability in Drug-Induced Parkinsonism. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 3749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.-W.; Kim, J.S.; Oh, M.; You, S.; Kim, Y.J.; Kim, J.; Kim, M.-J.; Chung, S.J. Clinical Features of Drug-Induced Parkinsonism Based on [18F] FP-CIT Positron Emission Tomography. Neurol. Sci. 2015, 36, 269–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nordström, A.L.; Nyberg, S.; Olsson, H.; Farde, L. Positron Emission Tomography Finding of a High Striatal D2 Receptor Occupancy in Olanzapine-Treated Patients. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1998, 55, 283–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raedler, T.J.; Knable, M.B.; Lafargue, T.; Urbina, R.A.; Egan, M.F.; Pickar, D.; Weinberger, D.R. In Vivo Determination of Striatal Dopamine D2 Receptor Occupancy in Patients Treated with Olanzapine. Psychiatry Res. 1999, 90, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyberg, S.; Eriksson, B.; Oxenstierna, G.; Halldin, C.; Farde, L. Suggested Minimal Effective Dose of Risperidone Based on PET-Measured D2 and 5-HT2A Receptor Occupancy in Schizophrenic Patients. Am. J. Psychiatry 1999, 156, 869–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinz, A.; Knable, M.B.; Weinberger, D.R. Dopamine D2 Receptor Imaging and Neuroleptic Drug Response. J. Clin. Psychiatry 1996, 57 (Suppl. 11), 84–88, discussion 89–93. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, P.T.; Frings, L.; Rücker, G.; Hellwig, S. (18)F-FDG PET in Parkinsonism: Differential Diagnosis and Evaluation of Cognitive Impairment. J. Nucl. Med. 2017, 58, 1888–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotomin, I.; Korotkov, A.; Solnyshkina, I.; Didur, M.; Cherednichenko, D.; Kireev, M. Parkinson’s Disease-Related Brain Metabolic Pattern Is Expressed in Schizophrenia Patients during Neuroleptic Drug-Induced Parkinsonism. Diagnostics 2022, 13, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagano, G.; Niccolini, F.; Politis, M. Imaging in Parkinson’s Disease. Clin. Med. 2016, 16, 371–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, P.H.; Kim, J.S.; Shin, D.H.; Yoon, S.-N.; Huh, K. Cardiac 123I-MIBG Scintigraphy in Patients with Drug Induced Parkinsonism. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2006, 77, 372–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, P.H.; Yeo, S.H.; Yong, S.W.; Kim, Y.J. Odour Identification Test and Its Relation to Cardiac 123I-Metaiodobenzylguanidine in Patients with Drug Induced Parkinsonism. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2007, 78, 1250–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.-S.; Oh, Y.-S.; Kim, Y.-I.; Yang, D.-W.; Chung, Y.-A.; You, I.-R.; Lee, K.-S. Combined Use of 123I-Metaiodobenzylguanidine (MIBG) Scintigraphy and Dopamine Transporter (DAT) Positron Emission Tomography (PET) Predicts Prognosis in Drug-Induced Parkinsonism (DIP): A 2-Year Follow-up Study. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2013, 56, 124–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shafie, M.; Mayeli, M.; Saeidi, S.; Mirsepassi, Z.; Abbasi, M.; Shafeghat, M.; Aghamollaii, V. The Potential Role of the Cardiac MIBG Scan in Differentiating the Drug-Induced Parkinsonism from Parkinson’s Disease. Clin. Park. Relat. Disord. 2022, 6, 100130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prasuhn, J.; Neumann, A.; Strautz, R.; Dreischmeier, S.; Lemmer, F.; Hanssen, H.; Heldmann, M.; Schramm, P.; Brüggemann, N. Clinical MR Imaging in Parkinson’s Disease: How Useful Is the Swallow Tail Sign? Brain Behav. 2021, 11, e02202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sung, Y.H.; Noh, Y.; Lee, J.; Kim, E.Y. Drug-Induced Parkinsonism versus Idiopathic Parkinson Disease: Utility of Nigrosome 1 with 3-T Imaging. Radiology 2016, 279, 849–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosottini, M.; Frosini, D.; Pesaresi, I.; Costagli, M.; Biagi, L.; Ceravolo, R.; Bonuccelli, U.; Tosetti, M. MR Imaging of the Substantia Nigra at 7 T Enables Diagnosis of Parkinson Disease. Radiology 2014, 271, 831–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, D.; Roggendorf, W.; Schröder, U.; Klein, R.; Tatschner, T.; Benz, P.; Tucha, O.; Preier, M.; Lange, K.W.; Reiners, K.; et al. Echogenicity of the Substantia Nigra: Association with Increased Iron Content and Marker for Susceptibility to Nigrostriatal Injury. Arch. Neurol. 2002, 59, 999–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehnert, S.; Reuter, I.; Schepp, K.; Maaser, P.; Stolz, E.; Kaps, M. Transcranial Sonography for Diagnosis of Parkinson’s Disease. BMC Neurol. 2010, 10, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouwmans, A.E.P.; Vlaar, A.M.M.; Mess, W.H.; Kessels, A.; Weber, W.E.J. Specificity and Sensitivity of Transcranial Sonography of the Substantia Nigra in the Diagnosis of Parkinson’s Disease: Prospective Cohort Study in 196 Patients. BMJ Open 2013, 3, e002613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olivares Romero, J.; Arjona Padillo, A.; Barrero Hernández, F.J.; Martín González, M.; Gil Extremera, B. Utility of Transcranial Sonography in the Diagnosis of Drug-Induced Parkinsonism: A Prospective Study. Eur. J. Neurol. 2013, 20, 1451–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, Y.-S.; Kwon, D.-Y.; Kim, J.-S.; Park, M.-H.; Berg, D. Transcranial Sonographic Findings May Predict Prognosis of Gastroprokinetic Drug-Induced Parkinsonism. Park. Relat. Disord. 2018, 46, 36–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.-Y.; Ahn, J.; Kim, T.W.; Jeon, B.S. Optical Coherence Tomography in Parkinson’s Disease: Is the Retina a Biomarker? J. Park. Dis. 2014, 4, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiménez, B.; Ascaso, F.J.; Cristóbal, J.A.; López del Val, J. Development of a Prediction Formula of Parkinson Disease Severity by Optical Coherence Tomography. Mov. Disord. 2014, 29, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, W.; Baek, S.U.; Oh, J.S.; Seo, S.Y.; Kim, J.S.; Han, Y.M.; Kim, M.S.; Kang, S.Y. Retinal Thickness and Its Interocular Asymmetry Between Parkinson’s Disease and Drug-Induced Parkinsonism. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2023, 38, e86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rissardo, J.P.; Caprara, A.L.F. Cinnarizine- and Flunarizine-Associated Movement Disorder: A Literature Review. Egyp. J. Neurol. Psych. Neurosurg. 2020, 56, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).