Pulpectomy vs. Pulpotomy as Alternative Emergency Treatments for Symptomatic Irreversible Pulpitis—A Multicenter Comparative Randomised Clinical Trial on Patient Perceptions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

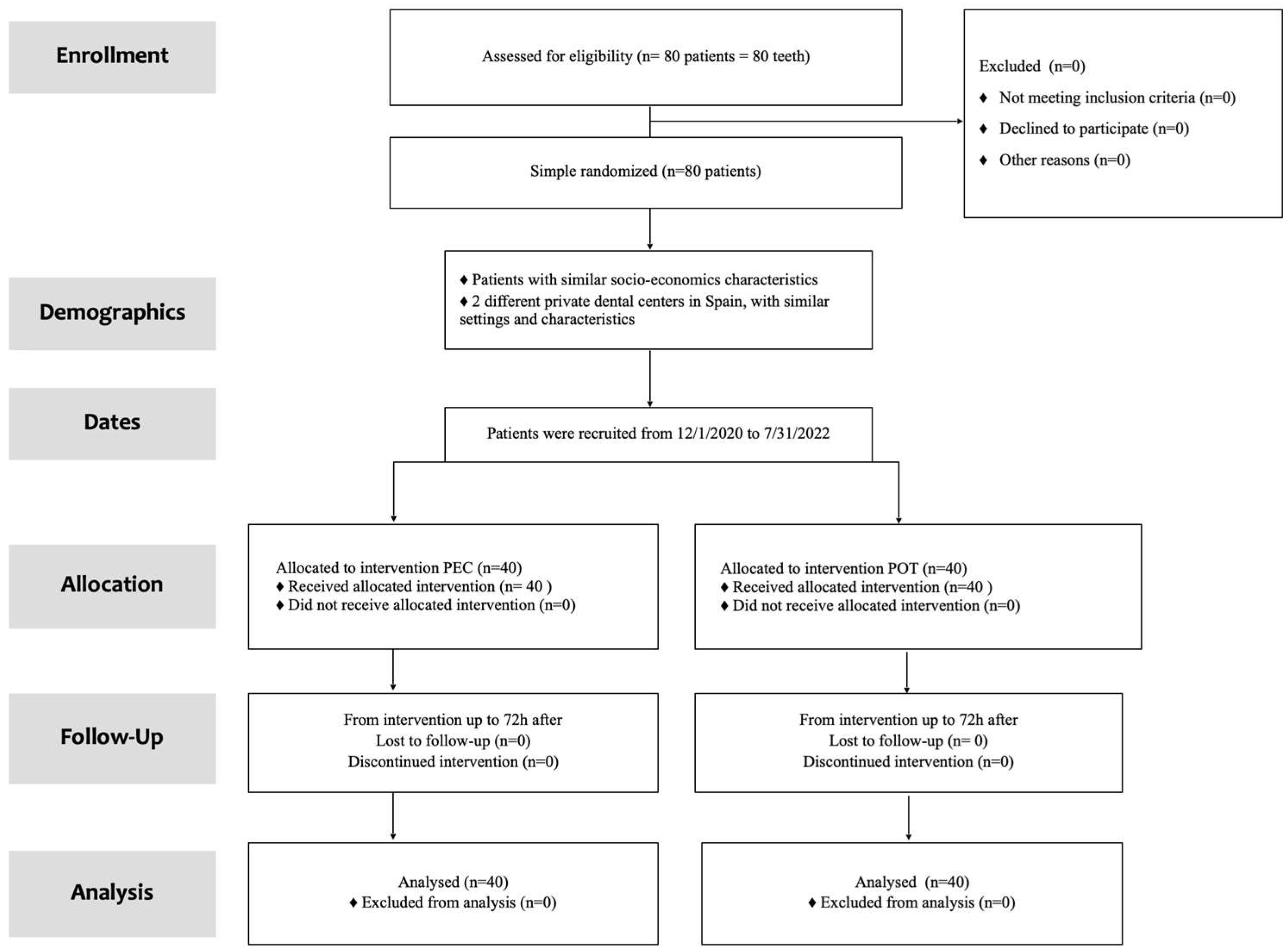

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Sample-Size Calculation

2.3. Outcomes

2.4. Patients

2.5. Interventions

- Isolation of the tooth with a rubber dam.

- Accessing to pulp chamber with a diamond bur.

- Confirmation of the presence of pulp bleeding.

- Removal of pulp tissue of the chamber with a round tungsten carbide bur.

- Use of cotton pellets soaked with sodium hypochlorite (NaOCl 5.25%).

- Waiting until the hemostasis is achieved.

- Placement of Teflon tape (PTFE) condensed on the chamber floor.

- Placement of a temporary restoration (Fermin, DETAX GmbH, Ettlingen, Germany).

- Occlusal reduction, verifying the absence of contact with 200μ articulating paper (Bausch Articulating Paper, NH, USA).

- Isolation of the tooth with a rubber dam.

- Accessing to pulp chamber with a diamond bur.

- Confirmation of the presence of pulp bleeding.

- Removal of pulp tissue of the chamber with a round tungsten carbide bur.

- Irrigation with sodium hypochlorite (NaCl at 5.25%) throughout the procedure, according to the operator’s preference.

- Determination of the working length for each canal using an Electronic Apex Locator (Root ZX mini, Morita, J. Morita Europe GmbH, Frankfurt, Germany) and a Pre-K file (EndoGal, Lugo, Spain).

- Root canal preparation using rotary cutting instruments with a reciprocating system (EndoGal, Lugo, Spain) up to WL and up to a minimum apical diameter of #25.

- Placement of Teflon tape (PTFE) condensed on the chamber floor. Calcium hydroxide was not used so as not to create differences between the two groups due to its anti-inflammatory effects.

- Placement of a temporary restoration (Fermin, DETAX GmbH, Ettlingen, Germany).

- Occlusal reduction, verifying the absence of contact with 200 μ articulating paper (Bausch Articulating Paper, NH, USA).

2.6. Data Collection and Management

- Before the intervention: the patient’s perception of current pain, anxiety, and pain sensation when chewing on the diseased side.

- Immediately after the intervention: the patient’s perception of the duration of treatment and the degree of discomfort during treatment.

- At the time intervals after the intervention: the patient’s perceived pain at 6, 24, and 72 h.

- The patient’s global satisfaction with the treatment 72 h after the procedure.

- Age.

- Gender.

- The number of teeth involved (FDI World Dental Federation notation).

- The cause of SIP (caries, previous restoration, cracks, periodontal affection, trauma, cusp fractures, and occlusal or cervical wear).

- The presence of primary acute apical periodontitis (AAP) with a percussion test before the intervention, in terms of Yes or No.

- Whether preoperative non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) had been taken by the patient, Yes or No.

- The time elapsed from pulp exposure to the end of the intervention in minutes.

- The postoperative chewing pain in terms of Yes or No.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

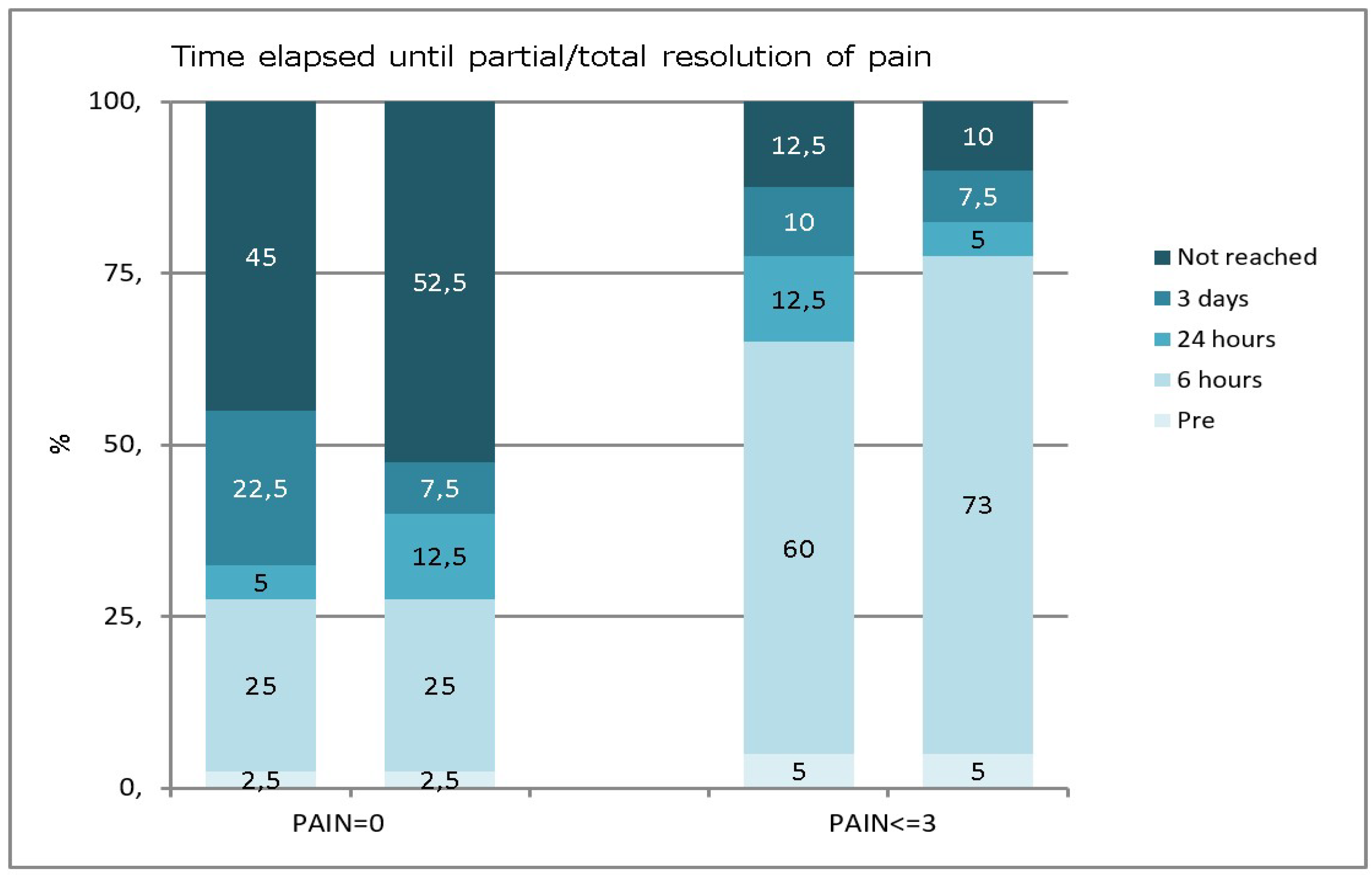

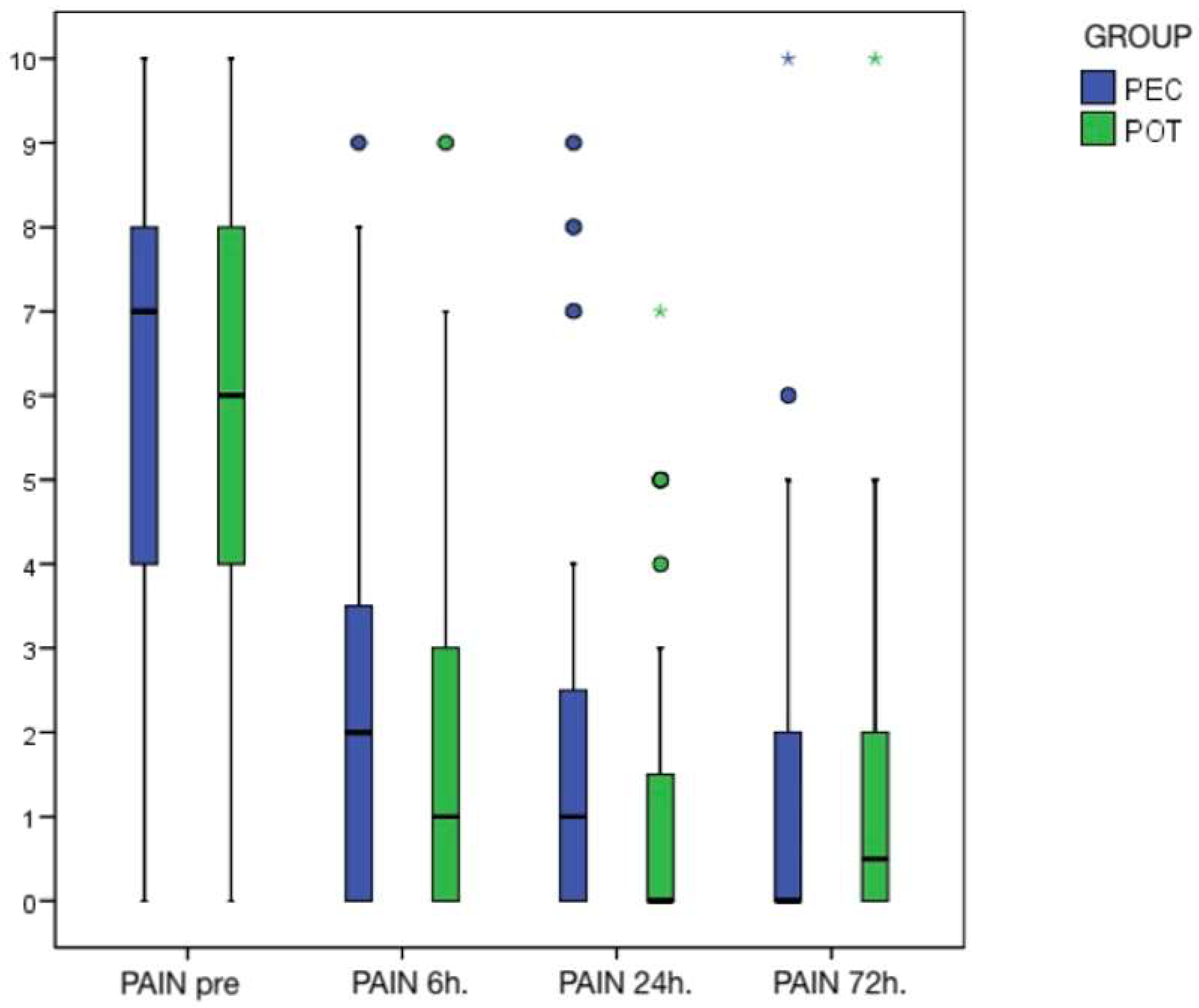

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abbott, P.V. Present status and future directions: Managing endodontic emergencies. Int. Endod. J. 2022, 55 (Suppl. S3), 778–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbott, P.V.; Yu, C. A clinical classification of the status of the pulp and the root canal system. Aust. Dent. J. 2007, 52 (Suppl. S1), S17–S31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakovljevic, A.; Jaćimović, J.; Aminoshariae, A.; Fransson, H. Effectiveness of vital pulp treatment in managing nontraumatic pulpitis associated with no or nonspontaneous pain: A systematic review. Int. Endod. J. 2022, 2022, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segura-Egea, J.J.; Cisneros-Cabello, R.; Llamas-Carreras, J.M.; Velasco-Ortega, E. Pain associated with root canal treatment. Int. Endod. J. 2009, 42, 614–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shueb, S.S.; Nixdorf, D.R.; John, M.T.; Alonso, B.F.; Durham, J. What is the impact of acute and chronic orofacial pain on quality of life? J. Dent. 2015, 43, 1203–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kérourédan, O.; Jallon, L.; Perez, P.; Germain, C.; Péli, J.F.; Oriez, D.; Fricain, J.C.; Arrivé, E.; Devillard, R. Efficacy of orally administered prednisolone versus partial endodontic treatment on pain reduction in emergency care of acute irreversible pulpitis of mandibular molars: Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2017, 18, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AAE. American Association of Endodontists Colleagues of Excellence: Management of Endodontic Emergencies: Pulpotomy Versus Pulpectomy. Colleagues Excell 2017, 2017, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Gemmell, A.; Stone, S.; Edwards, D. Investigating acute management of irreversible pulpitis: A survey of general dental practitioners in North East England. Br. Dent. J. 2020, 228, 521–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulsmann, M.; Peters, O.A.; Dummer, P.M. Mechanical preparation of root canals: Shaping goals, techniques and means. Endod. Top. 2005, 10, 30–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Society of Endodontology. Quality guidelines for endodontic treatment: Consensus report of the European Society of Endodontology. Int. Endod. J. 2006, 39, 921–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutmann, J.L. Minimally invasive dentistry (endodontics). J. Conserv. Dent. 2013, 16, 282–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolters, W.J.; Duncan, H.F.; Tomson, P.L.; Karim, I.E.; McKenna, G.; Dorri, M.; Stangvaltaite, L.; van der Sluis, L.W.M. Minimally invasive endodontics: A new diagnostic system for assessing pulpitis and subsequent treatment needs. Int. Endod. J. 2017, 50, 825–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ather, A.; Patel, B.; Gelfond, J.A.L.; Ruparel, N.B. Outcome of pulpotomy in permanent teeth with irreversible pulpitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 19664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clarkson, J.E.; Ramsay, C.R.; Mannocci, F.; Jarad, F.; Albadri, S.; Ricketts, D.; Tait, C.; Banerjee, A.; Deery, C.; Boyers, D.; et al. Pulpotomy for the Management of Irreversible Pulpitis in Mature Teeth (PIP): A feasibility study. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2022, 8, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, H.F.; El-Karim, I.; Dummer, P.M.H.; Whitworth, J.; Nagendrababu, V. Factors that influence the outcome of pulpotomy in permanent teeth. Int. Endod. J. 2023, 56 (Suppl. S2), 62–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eren, B.; Onay, E.O.; Ungor, M. Assessment of alternative emergency treatments for symptomatic irreversible pulpitis: A randomized clinical trial. Int. Endod. J. 2018, 51 (Suppl. S3), e227–e237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prati, C.; Pirani, C.; Zamparini, F.; Gatto, M.R.; Gandolfi, M.G. A 20-year historical prospective cohort study of root canal treatments. A multilevel analysis. Int. Endod. J. 2018, 51, 955–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antunes, L.S.; Souza, C.R.; Salles, A.G.; Gomes, C.C.; Antunes, L.A. Does Conventional Endodontic Treatment Impact Oral Health-related Quality of Life? A Systematic Review. Eur. Endod. J. 2017, 3, 2–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asgary, S.; Eghbal, M.J.; Shahravan, A.; Saberi, E.; Baghban, A.A.; Parhizkar, A. Outcomes of root canal therapy or full pulpotomy using two endodontic biomaterials in mature permanent teeth: A randomized controlled trial. Clin. Oral Investig. 2022, 26, 3287–3297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asgary, S.; Eghbal, M.J.; Fazlyab, M.; Baghban, A.A.; Ghoddusi, J. Five-year results of vital pulp therapy in permanent molars with irreversible pulpitis: A non-inferiority multicenter randomized clinical trial. Clin. Oral Investig. 2015, 19, 335–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madurantakam, P. Is pulpotomy an effective therapeutic option for the management of acute irreversible pulpitis in mature permanent teeth? Evid. Based Dent. 2022, 23, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galani, M.; Tewari, S.; Sangwan, P.; Mittal, S.; Kumar, V.; Duhan, J. Comparative evaluation of postoperative pain and success rate after pulpotomy and root canal treatment in cariously exposed mature permanent molars: A randomised controlled trial. J. Endod. 2017, 43, 1953–1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AAE. American Association of Endodontists Colleagues of Excellence: Endodontic Diagnosis. Colleagues Excell 2013, 2023, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan, H.F.; Galler, K.M.; Tomson, P.L.; Simon, S.; El-Karim, I.; Kundzina, R.; Krastl, G.; Dammaschke, T.; Fransson, H.; Markvart, M.; et al. European Society of Endodontology position statement: Management of deep caries and the exposed pulp. Int. Endod. J. 2019, 52, 923–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricucci, D.; Siqueira, J.F., Jr.; Li, Y.; Tay, F.R. Vital pulp therapy: Histopathology and histobacteriology-based guidelines to treat teeth with deep caries and pulp exposure. J. Dent. 2019, 86, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, L.M.; Ricucci, D.; Saoud, T.M.; Sigurdsson, A.; Kahler, B. Vital pulp therapy of mature permanent teeth with irreversible pulpitis from the perspective of pulp biology. Aust. Endod. J. 2020, 46, 154–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, Y.L.; Mann, V.; Rahbaran, S.; Lewsey, J.; Gulabivala, K. Outcome of primary root canal treatment: Systematic review of the literature-Part 2. Influence of clinical factors. Int. Endod. J. 2008, 41, 6–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnermeyer, D.; Dammaschke, T.; Lipski, M.; Schäfer, E. Effectiveness of diagnosing pulpitis: A systematic review. Int. Endod. J. 2022. epub ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patro, S.; Meto, A.; Mohanty, A.; Chopra, V.; Miglani, S.; Das, A.; Luke, A.M.; Hadi, D.A.; Meto, A.; Fiorillo, L.; et al. Diagnostic Accuracy of Pulp Vitality Tests and Pulp Sensibility Tests for Assessing Pulpal Health in Permanent Teeth: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmsmari, F.; Ruiz, X.F.; Miró, Q.; Feijoo-Pato, N.; Durán-Sindreu, F.; Olivieri, J.G. Outcome of Partial Pulpotomy in Cariously Exposed Posterior Permanent Teeth: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J. Endod. 2019, 45, 1296–1306.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashem, D.; Mannocci, F.; Patel, S.; Manoharan, A.; Brown, J.E.; Watson, T.F.; Banerjee, A. Clinical and radiographic assessment of the efficacy of calcium silicate indirect pulp capping: A randomized controlled clinical trial. J. Dent. Res. 2015, 94, 562–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Careddu, R.; Duncan, H.F. A prospective clinical study investigating the effectiveness of partial pulpotomy after relating preoperative symptoms to a new and established classification of pulpitis. Int. Endod. J. 2021, 54, 2156–2172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thong, I.S.K.; Jensen, M.P.; Miró, J.; Tan, G. The validity of pain intensity measures: What do the NRS, VAS, VRS, and FPS-R measure? Scand. J. Pain 2018, 18, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karcioglu, O.; Topacoglu, H.; Dikme, O.; Dikme, O. A systematic review of the pain scales in adults Which to use? Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2018, 36, 707–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pagé, M.G.; Katz, J.; Stinson, J.; Isaac, L.; Martin-Pichora, A.L.; Campbell, F. Validation of the numerical rating scale for pain intensity and unpleasantness in pediatric acute postoperative pain: Sensitivity to change over time. J. Pain 2012, 13, 359–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, L.; Vanschaayk, M.M.; Zhang, Y.; Fu, X.; Ji, P.; Yang, D. The prevalence of dental anxiety and its association with pain and other variables among adult patients with irreversible pulpitis. BMC Oral Health 2018, 18, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandraweera, L.; Goh, K.; Lai-Tong, J.; Newby, J.; Abbott, P. A survey of patients' perceptions about, and their experiences of, root canal treatment. Aust. Endod. J. 2019, 45, 225–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cushley, S.; Duncan, H.F.; Lappin, M.J.; Tomson, P.L.; Lundy, F.T.; Cooper, P.; Clarke, M.; El Karim, I.A. Pulpotomy for mature carious teeth with symptoms of irreversible pulpitis: A systematic review. J. Dent. 2019, 88, 103158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eghbal, M.J.; Haeri, A.; Shahravan, A.; Kazemi, A.; Moazami, F.; Mozayeni, M.A.; Saberi, E.; Samiei, M.; Vatanpour, M.; Akbarzade Baghban, A.; et al. Postendodontic Pain after Pulpotomy or Root Canal Treatment in Mature Teeth with Carious Pulp Exposure: A Multicenter Randomized Controlled Trial. Pain Res. Manag. 2020, 2020, 5853412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doğramacı, E.J.; Rossi-Fedele, G. Patient-related outcomes and Oral Health-Related Quality of Life in endodontics. Int. Endod. J. 2023, 56 (Suppl. S2), 169–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, J.M.; Pereira, J.F.; Marques, A.; Sequeira, D.B.; Friedman, S. Vital Pulp Therapy in Permanent Mature Posterior Teeth with Symptomatic Irreversible Pulpitis: A Systematic Review of Treatment Outcomes. Medicina 2021, 57, 573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duncan, H.F.; Nagendrababu, V.; El-Karim, I.A.; Dummer, P.M.H. Outcome measures to assess the effectiveness of endodontic treatment for pulpitis and apical periodontitis for use in the development of European Society of Endodontology (ESE) S3 level clinical practice guidelines: A protocol. Int. Endod. J. 2021, 54, 646–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Type of Criteria | Medical | Clinical |

|---|---|---|

| Inclusion |

|

|

| Exclusion |

|

|

| Variable | PEC-N (%) | POT-N (%) | p Value (Test) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Men | 20 (50%) | 20 (50%) | 1.000 (Chi2) |

| Women | 20 (50%) | 20 (50%) | ||

| Age | Years mean (SD=) | 50.8 (SD = 15.4) | 50.6 (SD = 15.2) | 0.985 (MW) |

| Tooth Type Group | Molar | 28 (70%) | 25 (62.5%) | 0.690 (Chi2) |

| Premolar | 12 (30%) | 13 (32.5%) | ||

| Anterior | 0 (0%) | 2 (5%) | ||

| Cause of pulpitis | Decay | 19 (47.5%) | 21 (52.5%) | 0.760 (Chi2) |

| Restoration | 13 (32.5%) | 10 (25%) | ||

| Others | 8 (20%) | 9 (22.5%) | ||

| Previous AAP present | 20 (50%) | 13 (32.5%) | 0.112 (Chi2) | |

| Previous NSAID intake | 17 (42.5%) | 20 (50%) | 0.501 (Chi2) |

| NSR Scores from 0 to 10 (Mean SD=); Median | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | PEC | POT | p Value (Test) |

| Previous pain | 6.0 (SD = 2.6); 7.0 | 5.6 (SD = 3.1); 6.0 | 0.763 (MW) |

| Previous anxiety | 3.2 (SD = 3.2); 2.0 | 3.3 (SD = 3.5); 2.5 | 0.908 (MW) |

| Previous chewing pain | 7.2 (SD = 2.7); 8.0 | 5.8 (SD = 3.6); 6.5 | 0.147 (MW) |

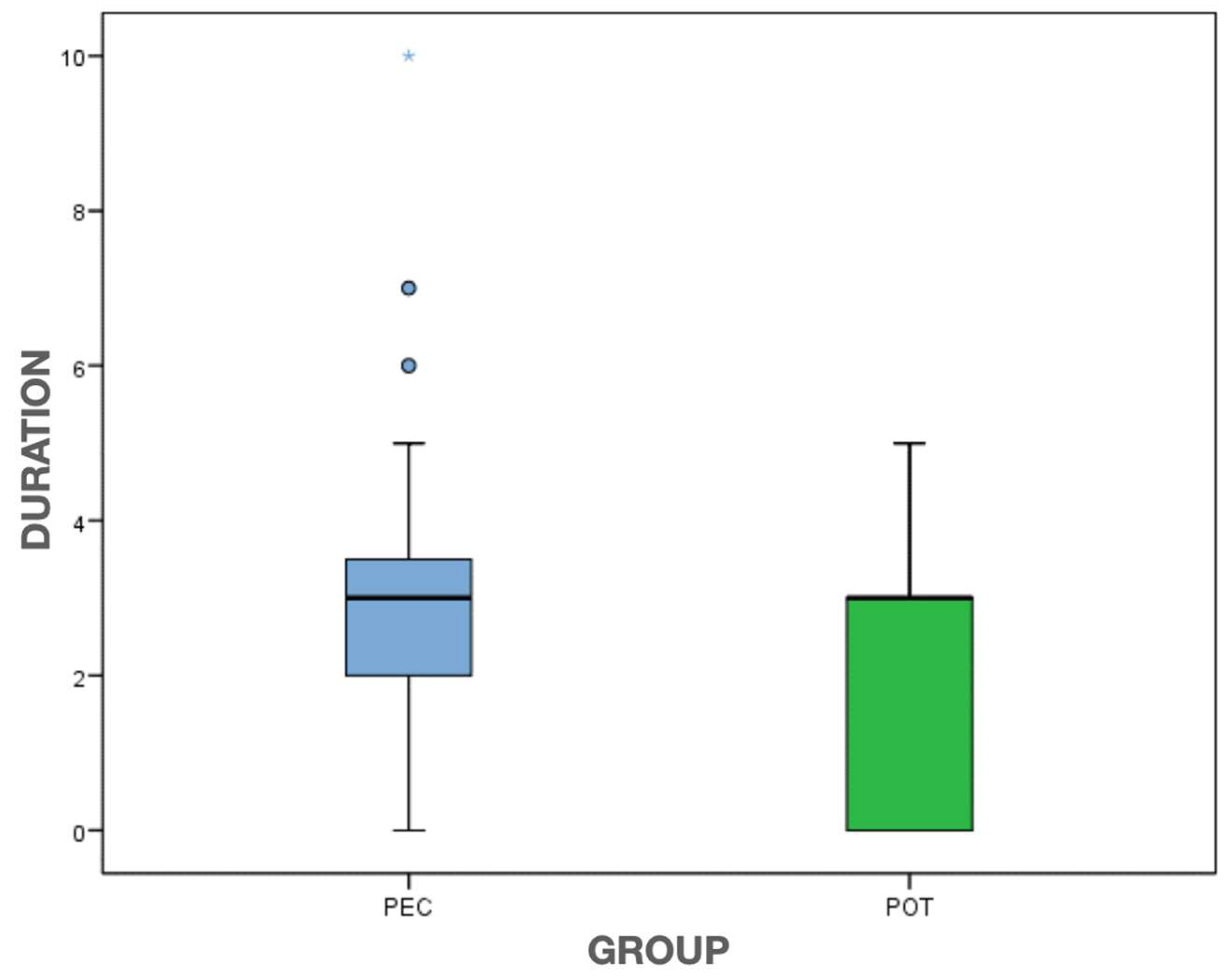

| Perceived duration | 3.1 (SD = 1.9); 3.0 | 2.0 (SD = 1.6); 3.0 | 0.021 * (MW) |

| Degree of discomfort | 1.5 (SD = 2.0); 0.0 | 1.6 (SD = 1.8); 1.0 | 0.453 (MW) |

| Pain after 6 h | 2.2 (SD = 2.6); 2.0 | 2.0 (SD = 2.3); 1.0 | |

| Pain after 24 h | 1.8 (SD = 2.3); 1.0 | 1.3 (SD = 2.0); 0.0 | |

| Pain after 3 days | 1.3 (SD = 2.1); 0.0 | 1.3 (SD = 2.0); 0.5 | 0.522 (ATS) |

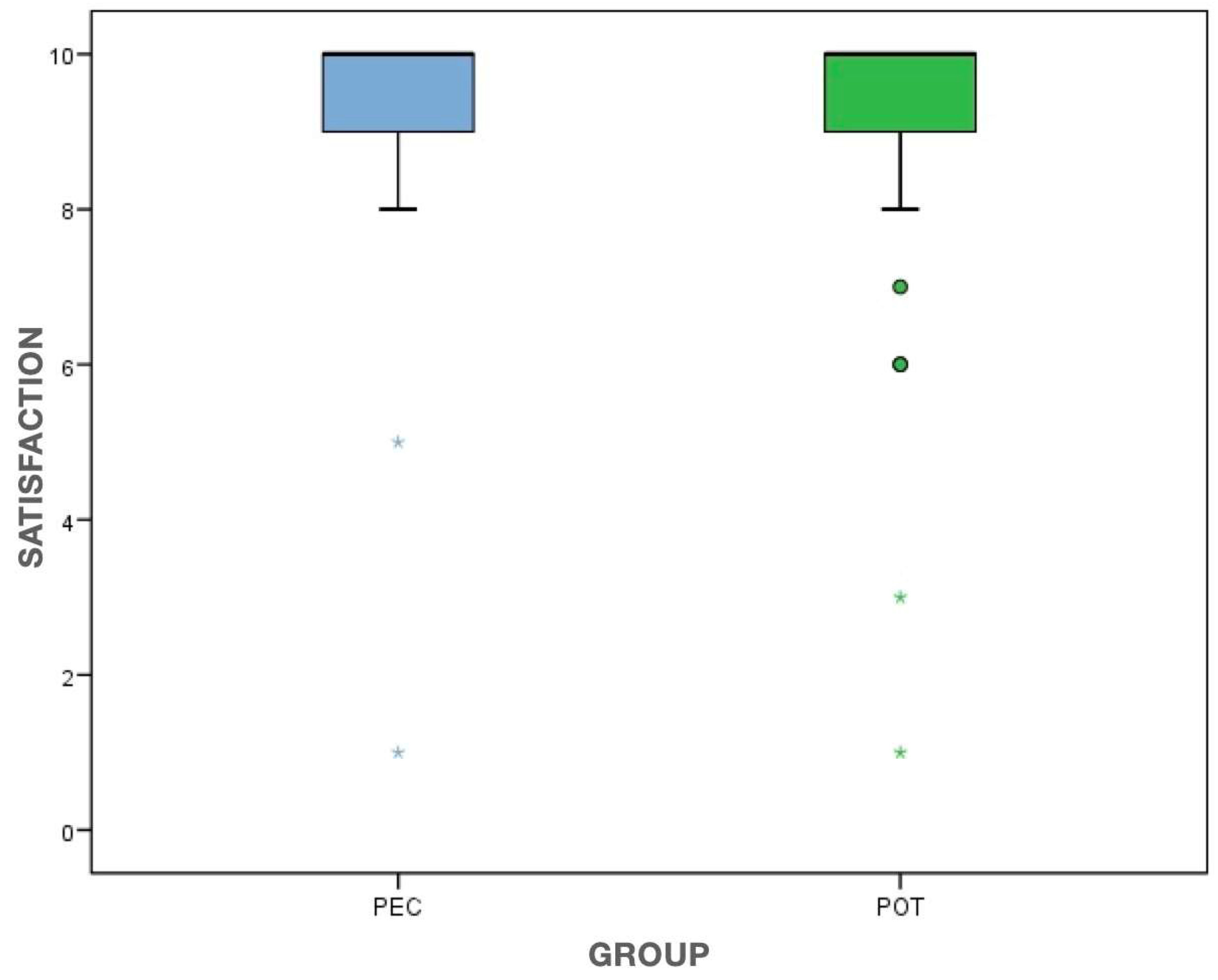

| Degree of satisfaction | 9.2 (SD = 1.7); 10.0 | 9.1 (SD = 2.0); 10.0 | 0.848 (MW) |

| PEC | POT | |

|---|---|---|

| Pre vs. 6 h | <0.001 *** | <0.001 *** |

| 6 h vs. 24 h | 0.849 | 0.003 ** |

| 24 h vs. 3 d | 0.354 | 1.000 |

| Beta | SE | CI 95% | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 9.76 | 0.20 | 9.36 10.2 | <0.001 *** |

| Pain 3 d | −0.50 | 0.09 | −0.67 −0.33 | <0.001 *** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Esteve-Pardo, G.; Barreiro-Gabeiras, P.; Esteve-Colomina, L. Pulpectomy vs. Pulpotomy as Alternative Emergency Treatments for Symptomatic Irreversible Pulpitis—A Multicenter Comparative Randomised Clinical Trial on Patient Perceptions. Clin. Pract. 2023, 13, 898-913. https://doi.org/10.3390/clinpract13040082

Esteve-Pardo G, Barreiro-Gabeiras P, Esteve-Colomina L. Pulpectomy vs. Pulpotomy as Alternative Emergency Treatments for Symptomatic Irreversible Pulpitis—A Multicenter Comparative Randomised Clinical Trial on Patient Perceptions. Clinics and Practice. 2023; 13(4):898-913. https://doi.org/10.3390/clinpract13040082

Chicago/Turabian StyleEsteve-Pardo, Guillem, Pedro Barreiro-Gabeiras, and Lino Esteve-Colomina. 2023. "Pulpectomy vs. Pulpotomy as Alternative Emergency Treatments for Symptomatic Irreversible Pulpitis—A Multicenter Comparative Randomised Clinical Trial on Patient Perceptions" Clinics and Practice 13, no. 4: 898-913. https://doi.org/10.3390/clinpract13040082

APA StyleEsteve-Pardo, G., Barreiro-Gabeiras, P., & Esteve-Colomina, L. (2023). Pulpectomy vs. Pulpotomy as Alternative Emergency Treatments for Symptomatic Irreversible Pulpitis—A Multicenter Comparative Randomised Clinical Trial on Patient Perceptions. Clinics and Practice, 13(4), 898-913. https://doi.org/10.3390/clinpract13040082