Abstract

Heart failure and mental health conditions frequently coexist and have a negative impact on health-related quality of life and prognosis. We aimed to evaluate depression and anxiety symptoms and to determine the association between psychological distress and cardiac parameters in heart failure with reduced and mildly reduced ejection fraction. A total of 43 patients (33 male, mean age 64 ± 10 years) with heart failure and left ventricular systolic dysfunction (29 with HFrEF, 14 with HFmrEF) underwent comprehensive echocardiographic evaluation. All study participants completed questionnaires for the assessment of depression (PHQ-9), anxiety (GAD-7), and health-related quality of life (MLHFQ). Ten (34%) patients with HFrEF and two (14%) participants with HFmrEF had moderate-to-severe depression symptoms. Significant anxiety symptoms were more frequent in HFrEF (10 vs. 2 patients; 34% vs. 14%). Poor quality of life was also more common among patients with HFrEF (17 vs. 5 patients; 59% vs. 36%), showing higher MLHFQ scores (p = 0.009). Moreover, PHQ-9, GAD-7, and MLHFQ scores showed significant correlations between NYHA class severity and the presence of peripheral edema. The symptoms of dyspnea correlated with both PHQ-9 and MLHFQ scores. Significant correlations were observed between MLHFQ scores and a large number of clinical features, such as exercise capacity, 6MWT distance, the need for furosemide, echocardiographic parameters (LVEDVI, LVESVI, LVEF, LVGLS, SVI), and laboratory variables (albumin, GFR, NT-proBNP). In the multiple linear regression analysis, dyspnea proved to be a significant predictor of higher PHQ-9 and MLHFQ scores, even after adjusting for potential confounders. High symptom burden due to psychological distress is common among patients with HFrEF and HFmrEF. More efficient control of congestion may improve depression, anxiety symptoms, and health-related quality of life.

1. Introduction

Heart failure (HF) remains a global healthcare challenge, with multimorbidity and the associated treatment burden affecting most patients. Although currently available guideline-directed medical and device therapy significantly improved morbidity and mortality, poor prognosis and low quality of life (QOL) remain further challenges [1,2].

Depression affects up to 20% of HF patients, negatively influencing disease outcomes and emotional well-being [1]. Both depression and HF show similar pathophysiological pathways, such as inflammation, increased platelet reactivity, arrhythmias, neuroendocrine dysregulation, high-risk behaviors, including smoking, poor physical health, and low adherence to treatment [3]. Depression has a negative impact on QOL, regardless of functional status, and emerged as an independent risk factor of poor outcomes in HF [3]. Current ESC HF guidelines provide recommendations for depression screening using validated questionnaires [1]. Medication, exercise training, and cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) improve depression symptoms in HF patients [3]. Moreover, left ventricular (LV) systolic dysfunction is predictive of depression and symptom severity in patients with myocardial infarction [4,5].

Other mental health conditions, such as anxiety, should also be promptly recognized and treated in HF [1]. Symptoms of anxiety are more common in HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) than in HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) [6]. Both anxiety and depression are reliable predictors of QOL in HFrEF [7].

Anxiety and depression worsen not only HF but also cardiovascular disease generally. In fact, anxiety proved to be a better predictor of serotonin-mediated platelet reactivity than depression in patients with stable coronary artery disease on dual antiplatelet therapy with clopidogrel plus aspirin three months after an acute coronary syndrome [8].

Adverse LV remodeling has a negative impact on morbidity and mortality in patients with HF [9]. LV volumes (especially LVESV) predict HF outcomes even after adjusting for LVEF and infarct size [10]. Moreover, the short-term benefits of drug or device therapy on LV remodeling, as assessed by changes in LVEF, LVESV, and LVEDV, are associated with better longer-term outcomes [11]. Sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors improve HF beyond their glucoretic and natriuretic effect, by enhancing myocardial energetics [12,13]. Empaglifozin ameliorates LV remodeling, improves functional capacity [14], reduces mortality and hospitalization [15], and increases QOL [14,16].

The aim of our study was to evaluate symptom burden due to psychological distress in HFrEF and HF with mildly reduced ejection fraction (HFmrEF), and to determine the relationship between depression and anxiety and heart structure and function as assessed by echocardiography, and other clinical and laboratory parameters. Moreover, we tried to identify cardiac ultrasound parameters indicative of depression and anxiety in HFrEF and HFmrEF, in order to find subgroups of patients at higher risk of developing mental health conditions for targeted screening.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Cohort

Forty-three patients with left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) < 50% were enrolled in a prospective, single-center study, during January and November 2022 in Târgu Mureș, Romania. Inclusion criteria were the diagnosis of HFrEF or HFmrEF according to currently available guidelines [1], New York Heart Association (NYHA) class I-III, hemodynamic stability (regarding heart rate, blood pressure, clinical congestion), and willingness to participate. Exclusion criteria were signs and symptoms of infection, poor kidney function (estimated glomerular filtration rate (GFR) < 20 mL/min/1.73 m2 using the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) equation), known liver disease, autoimmune disorders, and cancer. The recruited patients were either outpatients or inpatients hospitalized for worsening heart failure, assessed after decongestion and right before discharge. The outpatients were on standard HF medication for the last 3 months. Each participant underwent systematic data collection regarding routine demographic, clinical, laboratory, and echocardiographic data. A lung ultrasound (LUS) was also performed for the assessment of pulmonary congestion. Patients were screened for depression symptoms and anxiety. Health-related quality of life (HRQL) was also evaluated.

The study complies with the Declaration of Helsinki. The institutional ethics committee approved the study protocol (7716/02.07.2021, Clinical County Hospital Mureș), and participants provided written informed consent before recruiting.

2.2. Cardiac and Lung Ultrasound

Echocardiography was carried out using a Philips Epiq7 ultrasound machine (Philips Ultrasound, Inc., Bothell, WA, USA) and a Philips X5-1 xMATRIX array transducer (1–5 MHz) according to current recommendations [17,18,19]. LVEF was assessed using the biplane method of disks (modified Simpson’s method). Global longitudinal strain measurements were made in the three standard apical views and then averaged. LV and left atrial (LA) volumes were acquired by 2D echocardiography and normalized by body surface area (BSA). Averaged e’ from medial and lateral sites of the mitral annulus was used for the calculation of E/e’.

An eight-zone LUS protocol was performed on every participant. Each hemithorax was divided into four zones assessing the anterior and lateral chest and scanning for B-lines [20]. Patients were evaluated in a semirecumbent position, using the same cardiac probe (Philips X5-1 xMATRIX, 1–5 MHz) positioned perpendicular to the ribs. Imaging depth was tailored to the patient. All quadrants were screened, and the following threshold was applied: normal (0–2 B-lines/zone) and abnormal (≥3 B-lines/zone) [20].

2.3. Six-Minute Walking Test and Ankle-Brachial Index Assessment

For further risk stratification, the six-minute walking (6MWT) distance was also measured based on available guidelines [21].

Ankle-brachial index testing using standard peripheral CW Doppler (5 MHz) was carried out for the assessment of subclinical peripheral arterial disease (PAD), and a threshold of ≤0.9 was used.

2.4. Mental Health Status and Quality of Life in Heart Failure

The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) and Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) were applied to evaluate coexisting depression and anxiety [22,23,24]. Depression symptoms were categorized using PHQ-9 scores, and values ≥ 10 were considered significant [23]. The same cut-off values were established for anxiety symptoms as determined by GAD-7 (scores ≥ 10 were considered relevant) [24]. HRQL was assessed with Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire (MLHFQ), comprising 21 items, which addressed emotional, physical, and socioeconomic aspects of heart failure [25]. Scores ≥ 24 on the MLHFQ were considered consistent with a moderate-to-poor HRQL [26].

2.5. Laboratory Data

Blood samples were collected after 12-h fasting in red-top and purple-top tubes (Becton-Dickinson Vacutainer Systems, Wokingham, Berkshire, UK). The tubes without additives were centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 min to separate the serum. Total-, LDL-, and HDL-cholesterol, serum triglycerides, creatinine, albumin, serum iron, ferritin, and C-reactive protein (CRP) levels were measured with commercial biochemical kits on an Arhitect C4000 (Abbott Laboratories, Diagnostic Division, Abbott Park, IL, USA). Plasma fibrinogen was determined using a coagulometric method with Multifibren U reagent on Sysmex CA-1500 (Sysmex Corporation, Kobe, Japan). Serum N-terminal pro B-type natriuretic peptide levels (NT-proBNP) were measured using an electrochemiluminescent immunoassay on Elecsys 2010 (Roche Diagnostics International, Rotkreuz, Switzerland). Tripotassium ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (K3 EDTA) precoated tubes were used for complete blood count analysis on a Mindray BC6000 (Mindray Global, Shenzhen, China).

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Data distribution was assessed using Kolmogorov–Smirnov and Shapiro–Wilk tests. Paired t-test was performed for variables showing Gaussian distribution. The Mann–Whitney U test and Spearman rank correlation analysis were applied for variables showing skewed distribution. Categorical variables were quantified for absolute and relative frequency and the 2 × 2 or 3 × 2 contingency tables were analyzed with the χ2 test. p-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Data processing was performed using Microsoft Excel 2016 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) and GraphPad Prism 9.5.0 (GraphPad Software LLC., San Diego, CA, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Study Group Characteristics

Twenty-nine patients with HFrEF and fourteen patients with HFmrEF were included in the study (Table 1 and Table 2). A significantly higher number of participants with HFrEF were recruited before discharge, rather than from ambulatory care (22 (69%) vs. 2 (14%), p = 0.004). Patients with HFmrEF showed better exercise capacity (p = 0.049), had higher levels of serum iron (p = 0.015), lower NT-proBNP values (p = 0.015), and a less frequent need for furosemide for symptom relief (p = 0.036). Study participants with HFrEF had increased LA volume indexes (LAVI), LV end-diastolic and end-systolic volume indexes (LVEDVI, LVESVI), and low stroke volume indexes (SVI).

Table 1.

Clinical, laboratory, and ultrasound variables in HF patients.

Table 2.

Mental Health and HRQL in HF patients.

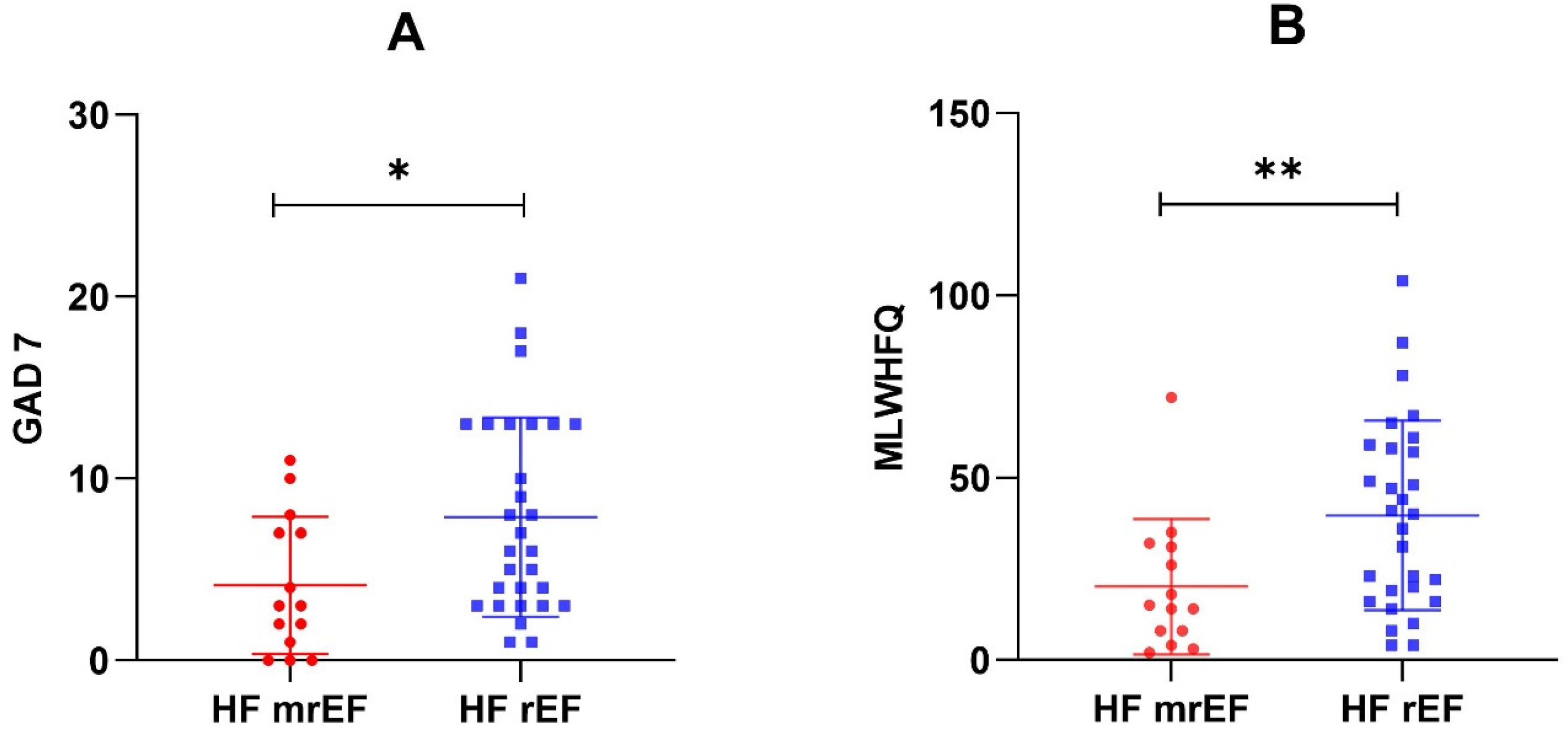

Ten (34%) patients with HFrEF had moderate-to-severe depression symptoms, compared to only two (14%) participants with HFmrEF. Significant anxiety symptoms were also more frequent in HFrEF: 10 (34%) vs. 2 (14%). Reduced HRQL was more common among patients with HFrEF: 17 (59%) vs. 5 (36%), showing higher MLHFQ scores (p = 0.009) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

GAD-7 scores (A) and MLHFQ scores (B) in the two EF subgroups. * p = 0.026; ** p = 0.009.

3.2. Correlations for GAD-7, PHQ-9, and MLHFQ

Table 3 summarizes the association between questionnaire scores and several parameters. GAD-7, PHQ-9, and MLHFQ scores showed significant correlations with NYHA class severity and the presence of peripheral edema. Symptoms of dyspnea correlated with both PHQ-9 and MLHFQ scores. PHQ-9 scores also showed significant correlations with echocardiographic parameters, such as LAVI and SVI. Significant correlations were observed between HRQL scores and a large number of clinical and paraclinical characteristics: exercise capacity, 6MWT distance, the need for loop diuretics, cardiac ultrasound imaging measurements–LVEDVI, LVESVI, LVEF, LVGLS, SVI, and different laboratory variables–albumin, GFR, NT-proBNP.

Table 3.

Correlations for GAD-7, PHQ-9, and MLHFQ scores in the overall group (n = 43).

GAD-7 scores showed statistically significant positive correlations with PHQ-9 scores (Spearman’s R = 0.608, p < 0.0001) and MLHFQ scores (Spearman’s R = 0.521, p = 0.0003). PHQ-9 scores also correlated with MLHFQ scores (Spearman’s R = 0.683, p < 0.0001).

3.3. Multivariate Linear Regression Models for PHQ-9 and MLHFQ

Multiple linear regression models were set up for the determinants of PHQ-9 scores as a continuous variable. In the first model, the symptom of dyspnea proved to be the only significant predictor, which remained significant, even when adjusted for the presence of peripheral edema, LAVI, LVGLS, and SVI (Model 1, Table 4a). Two different models were constructed for MLHFQ (Table 4b). The presence of dyspnea also predicted MLHFQ scores, maintaining its significance when adjusted for LAVI, LVEDVI, LVESVI, LVEF (Model 2), and peripheral edema, LVESVI, LVEF, exercise capacity, and serum albumin (Model 3).

Table 4.

(a). Multivariate linear regression analysis of the factors correlated with PHQ-9 scores in the overall patient group. (b). Multivariate linear regression analysis of the factors correlated with MLHFQ scores in the overall patient group (n = 43).

4. Discussion

Depression is common among patients with HF, negatively affecting healthcare-related economic burdens [3]. Two meta-analyses conducted 10 years apart showed an increasing prevalence of depression in HF—21.5% vs. 29% [27,28]. Age might also play an important role in the frequency of depression symptoms and their impact on mortality. One-year mortality rates were significantly higher in elderly patients (≥70 years), who were associated with higher Beck Depression Inventory scores [29]. We found no significant correlations between age and PHQ-9 scores, but our study population was younger with a mean age of 64 ± 10 years.

The relationship between HF and depression is bidirectional—depression increases the risk of developing HF, especially in specific populations, whereas patients with HF frequently associate comorbid depression, both shown to negatively impact HRQL. Moreover, HF and depression share similar pathophysiological mechanisms, and the inflammatory pathway is considered one of great importance [3]. We failed to find significant correlations between PHQ-9 scores and biomarkers of inflammation, such as neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, CRP, and fibrinogen. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratios of 1.57 or higher proved to be predictors of severe depression in patients diagnosed with depression [30]. Our patients had median neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratios of 2.3 (1.89–3.08), but values showed no association with PHQ-9 scores.

Anxiety and depression symptoms are significantly more common in outpatients with HFpEF when compared to HFrEF [6]. Significant anxiety symptoms using the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory were reported in HFrEF (31.6% and 27.2%) [31]. Moreover, 34% of our patients with HFrEF had moderate-to-severe anxiety symptoms. Trait anxiety failed to show prognostic value in predicting all-cause mortality at 18 months, all-cause death, or readmission, and cardiovascular mortality or readmission in HFrEF, but not in HFpEF [31].

NYHA class showed significant positive correlations with all assessed scores (GAD-7, PHQ-9, MLHFQ). Dyspnea remained significant for predicting depression symptoms and QOL even after adapting for confounders. Moreover, MLHFQ scores correlated with the need for furosemide and NT-proBNP levels. Residual congestion estimated by LUS in decompensated HF was associated with increased all-cause mortality during a 4-year follow-up [32]. This highlights the importance of patient management after discharge and during regular follow-ups, in order to achieve decongestion and prevent episodes of cardiac decompensation and disease progression.

We established LAVI and SVI as potential predictors for depression symptoms. These echocardiographic parameters might help healthcare professionals to identify patients at higher risk of developing depression in HFrEF and HFmrEF. In the MIND-IT study, patients with myocardial infarction and lower EF presented a higher risk of developing depression, especially men [4]. In our study cohort, LVEF (p = 0.093) and LVGLS (p = 0.067) showed a tendency towards a stronger increase in depression symptom scores but did not reach statistical significance.

Depression and 6MWT distance were associated with poor quality of life in patients with advanced HF, who were candidates for left ventricular assist devices [33]. We found significant correlations between exercise capacity, 6MWT distance, and MLHFQ scores. The HF-ACTION trial randomized patients with HF and NYHA class I-IV, LVEF ≤ 35%, to aerobic exercise training or education and guideline-directed therapy, with exercise leading to a significant reduction in depression symptoms at 3 and 12 months [34]. In a meta-analysis on CBT in HF and comorbid depression, patients reported improvement in depression symptoms and QOL after finishing treatment sessions [35].

The routine prescription of pharmacotherapy for depression in HF should be withheld. In the double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized MOOD-HF clinical trial, which included participants with HF and NYHA class II-IV, LVEF < 45%, treatment with escitalopram for 18 months showed no significant reduction in all-cause mortality or hospitalization, nor improvement in depression symptoms [36]. Currently, available ESC guidelines for HF management recommend avoiding the treatment of depression with tricyclic antidepressants because of their possible side effects [1].

5. Conclusions

Depression and anxiety symptoms are prevalent among patients with HFrEF and HFmrEF. GAD-7 and MLHFQ scores are significantly higher in HFrEF, indicating greater symptom burden. Dyspnea proved to be a significant predictor of depression symptoms and HRQL in HF with left ventricular systolic dysfunction. A number of echocardiographic parameters showed significant correlations with PHQ-9 and MLHFQ scores, thus identifying a subgroup of patients more vulnerable to developing depression for future targeted screening.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.M.S. and E.E.N.; writing—original draft preparation, T.M.S. and E.E.N.; writing—review and editing, T.M.S., E.E.N. and A.F.; data collection, T.M.S., Á.K., E.H., H.-L.G.-K. and M.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Collegium Talentum 2022 Programme of Hungary research bursary for first author T.M.S.

Limitations

The main limitation of our study is the small number of participants. Also, baseline differences between the two groups may influence the results. Therefore, larger studies are required to provide more accurate and reliable results.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study complies with the Declaration of Helsinki. The institutional ethics committee approved the study protocol (7716/02.07.2021, Clinical County Hospital Mureș).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed written consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Publicly archived datasets analyzed during the study can be found under the following link: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.21895845.v1, accessd on 13 January 2023.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- McDonagh, T.A.; Metra, M.; Adamo, M.; Gardner, R.S.; Baumbach, A.; Bohm, M.; Burri, H.; Butler, J.; Celutkiene, J.; Chioncel, O.; et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 3599–3726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidenreich, P.A.; Bozkurt, B.; Aguilar, D.; Allen, L.A.; Byun, J.J.; Colvin, M.M.; Deswal, A.; Drazner, M.H.; Dunlay, S.M.; Evers, L.R.; et al. 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure: Executive Summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2022, 145, E876–E894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sbolli, M.; Fiuzat, M.; Cani, D.; O′Connor, C.M. Depression and heart failure: The lonely comorbidity. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2020, 22, 2007–2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Melle, J.P.; de Jonge, P.; Ormel, J.; Crijns, H.; van Veldhuisen, D.J.; Honig, A.; Schene, A.H.; van den Berg, M.P.; Investigators, M.-I. Relationship between left ventricular dysfunction and depression following myocardial infarction: Data from the MIND-IT. Eur. Heart J. 2005, 26, 2650–2656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagherian-Sararoudi, R.; Gilani, B.; Bahrami Ehsan, H.; Sanei, H. Relationship between left ventricular ejection fraction and depression following myocardial infarction: An original article. ARYA Atheroscler. 2013, 9, 16–21. [Google Scholar]

- Bekfani, T.; Nisser, J.; Derlien, S.; Hamadanchi, A.; Frob, E.; Dannberg, G.; Lichtenauer, M.; Smolenski, U.C.; Lehmann, G.; Mobius-Winkler, S.; et al. Psychosocial factors, mental health, and coordination capacity in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction compared with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. Esc. Heart Fail. 2021, 8, 3268–3278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fino, P.; Sousa, R.M.; Carvalho, R.; Sousa, N.; Almeida, F.; Pereira, V.H. Cognitive performance is associated with worse prognosis in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. Esc. Heart Fail. 2020, 7, 3059–3066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafar, M.U.; Paz-Yepes, M.; Shimbo, D.; Vilahur, G.; Burg, M.M.; Chaplin, W.; Fuster, V.; Davidson, K.W.; Badimon, J.J. Anxiety is a better predictor of platelet reactivity in coronary artery disease patients than depression. Eur. Heart J. 2010, 31, 1573–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstam, M.A.; Kramer, D.G.; Patel, A.R.; Maron, M.S.; Udelson, J.E. Left Ventricular Remodeling in Heart Failure Current Concepts in Clinical Significance and Assessment. JACC-Cardiovasc. Imaging 2011, 4, 98–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, H.D.; Norris, R.M.; Brown, M.A.; Brandt, P.W.T.; Whitlock, R.M.L.; Wild, C.J. Left-Ventricular End-Systolic Volume as the Major Determinant of Survival after Recovery from Myocardial-Infarction. Circulation 1987, 76, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, D.G.; Trikalinos, T.A.; Kent, D.M.; Antonopoulos, G.V.; Konstam, M.A.; Udelson, J.E. Quantitative Evaluation of Drug or Device Effects on Ventricular Remodeling as Predictors of Therapeutic Effects on Mortality in Patients With Heart Failure and Reduced Ejection Fraction A Meta-Analytic Approach. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2010, 56, 392–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvaraj, S.; Fu, Z.X.; Jones, P.; Kwee, L.C.; Windsor, S.L.; Ilkayeva, O.; Newgard, C.B.; Margulies, K.B.; Husain, M.; Inzucchi, S.E.; et al. Metabolomic Profiling of the Effects of Dapagliflozin in Heart Failure with Reduced Ejection Fraction: DEFINE-HF. Circulation 2022, 146, 808–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos-Gallego, C.G.; Mayr, M.; Badimon, J. SGLT2 Inhibitors in Heart Failure: Targeted Metabolomics and Energetic Metabolism. Circulation 2022, 146, 819–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos-Gallego, C.G.; Vargas-Delgado, A.P.; Requena-Ibanez, J.A.; Garcia-Ropero, A.; Mancini, D.; Pinney, S.; Macaluso, F.; Sartori, S.; Roque, M.; Sabatel-Perez, F.; et al. Randomized Trial of Empagliflozin in Nondiabetic Patients with Heart Failure and Reduced Ejection Fraction. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2021, 77, 243–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Packer, M.; Anker, S.D.; Butler, J.; Filippatos, G.; Pocock, S.J.; Carson, P.; Januzzi, J.; Verma, S.; Tsutsui, H.; Brueckmann, M.; et al. Cardiovascular and Renal Outcomes with Empagliflozin in Heart Failure. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 1413–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Requena-Ibanez, J.A.; Santos-Gallego, C.G.; Rodriguez-Cordero, A.; Vargas-Delgado, A.P.; Badimon, J.J. Empagliflozin improves quality of life in nondiabetic HFrEF patients. Sub-analysis of the EMPATROPISM trial. Diabetes Metab. Syndr.-Clin. Res. Rev. 2022, 16, 102417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, R.M.; Badano, L.P.; Mor-Avi, V.; Afilalo, J.; Armstrong, A.; Ernande, L.; Flachskampf, F.A.; Foster, E.; Goldstein, S.A.; Kuznetsova, T.; et al. Recommendations for Cardiac Chamber Quantification by Echocardiography in Adults: An Update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2015, 28, 1-U170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lancellotti, P.; Tribouilloy, C.; Hagendorff, A.; Popescu, B.A.; Edvardsens, T.; Pierard, L.A.; Badano, L.; Zamorano, J.L.; European Assoc Cardiovasc, I. Recommendations for the echocardiographic assessment of native valvular regurgitation: An executive summary from the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. Eur. Heart J.-Cardiovasc. Imaging 2013, 14, 611–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, C.; Rahko, P.S.; Blauwet, L.A.; Canaday, B.; Finstuen, J.A.; Foster, M.C.; Horton, K.; Ogunyankin, K.O.; Palma, R.A.; Velazquez, E.J. Guidelines for Performing a Comprehensive Transthoracic Echocardiographic Examination in Adults: Recommendations from the American Society of Echocardiography. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2019, 32, 1–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volpicelli, G.; Mussa, A.; Garofalo, G.; Cardinale, L.; Casoli, G.; Perotto, F.; Fava, C.; Frascisco, M. Bedside lung ultrasound in the assessment of alveolar-interstitial syndrome. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2006, 24, 689–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, A.E.; Spruit, M.A.; Troosters, T.; Puhan, M.A.; Pepin, V.; Saey, D.; McCormack, M.C.; Carlin, B.W.; Sciurba, F.C.; Pitta, F.; et al. An official European Respiratory Society/American Thoracic Society technical standard: Field walking tests in chronic respiratory disease. Eur. Respir. J. 2014, 44, 1428–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B.W. The PHQ-9-Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2001, 16, 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, K.N.; Kalogeropoulos, A.P.; Dunbar, S.B.; Butler, J.; Georgiopoulou, V.V. Depression in heart failure: Can PHQ-9 help? Int. J. Cardiol. 2016, 221, 246–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flint, K.M.; Fairclough, D.L.; Spertus, J.A.; Bekelman, D.B. Does heart failure-specific health status identify patients with bothersome symptoms, depression, anxiety, and/or poorer spiritual well-being? Eur. Heart J.-Qual. Care Clin. Outcomes 2019, 5, 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rector, T.S.; Tschumperlin, L.K.; Kubo, S.H.; Bank, A.J.; Francis, G.S.; McDonald, K.M.; Cohn, J.N. Clinically Significant Improvements in the Living with Heart-Failure Questionnaire Score as Judged by Patients with Heart-Failure. Qual. Life Res. 1994, 3, 60–61. [Google Scholar]

- Behlouli, H.; Feldman, D.E.; Ducharme, A.; Frenette, M.; Giannetti, N.; Grondin, F.; Michel, C.; Sheppard, R.; Pilote, L. Identifying relative Cut-Off Scores with Neural Networks for Interpretation of the Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire. In Proceedings of the Annual International Conference of the IEEE-Engineering-in-Medicine-and-Biology-Society, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 3–6 September 2009; p. 6242. [Google Scholar]

- Rutledge, T.; Reis, V.A.; Linke, S.E.; Greenberg, B.H.; Mills, P.J. Depression in heart failure-A meta-analytic review of prevalence, intervention effects, and associations with clinical outcomes. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2006, 48, 1527–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokoreli, I.; Vries, J.J.G.; Pauws, S.C.; Steyerberg, E.W. Depression and anxiety as predictors of mortality among heart failure patients: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart Fail. Rev. 2016, 21, 49–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regan, J.A.; Kitzman, D.W.; Leifer, E.S.; Kraus, W.E.; Fleg, J.L.; Forman, D.E.; Whellan, D.J.; Wojdyla, D.; Parikh, K.; O′onnor, C.M.; et al. Impact of Age on Comorbidities and Outcomes in Heart Failure with Reduced Election Fraction. JACC-Heart Fail. 2019, 7, 1056–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunbul, E.A.; Sunbul, M.; Yanartas, O.; Cengiz, F.; Bozbay, M.; Sari, I.; Gulec, H. Increased Neutrophil/Lymphocyte Ratio in Patients with Depression is Correlated with the Severity of Depression and Cardiovascular Risk Factors. Psychiatry Investig. 2016, 13, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.K.; Hsu, B.C.; Li, Y.D.; Chen, C.H.; Lin, J.W.; Chien, C.Y.; Weng, C.Y. Prognostic Value of Anxiety Between Heart Failure with Reduced Ejection Fraction and Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2019, 8, e010739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceriani, E.; Casazza, G.; Peta, J.; Torzillo, D.; Furlotti, S.; Cogliati, C. Residual congestion and long-term prognosis in acutely decompensated heart failure patients. Intern. Emerg. Med. 2020, 15, 719–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascino, T.M.; Kittleson, M.M.; Lala, A.; Stehlik, J.; Palardy, M.; Pamboukian, S.V.; Ewald, G.A.; Mountis, M.M.; Horstmanshof, D.A.; Robinson, S.W.; et al. Comorbid Conditions and Health-Related Quality of Life in Ambulatory Heart Failure Patients REVIVAL (Registry Evaluation of Vital Information for VADs in Ambulatory Life REVIVAL). Circ.-Heart Fail. 2020, 13, e006858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumenthal, J.A.; Babyak, M.A.; O′Connor, C.; Keteyian, S.; Landzberg, J.; Howlett, J.; Kraus, W.; Gottlieb, S.; Blackburn, G.; Swank, A.; et al. Effects of Exercise Training on Depressive Symptoms in Patients With Chronic Heart Failure The HF-ACTION Randomized Trial. JAMA-J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2012, 308, 465–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeyanantham, K.; Kotecha, D.; Thanki, D.; Dekker, R.; Lane, D.A. Effects of cognitive behavioural therapy for depression in heart failure patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart Fail. Rev. 2017, 22, 731–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angermann, C.E.; Gelbrich, G.; Stork, S.; Gunold, H.; Edelmann, F.; Wachter, R.; Schunkert, H.; Graf, T.; Kindermann, I.; Haass, M.; et al. Effect of Escitalopramon All-Cause Mortality and Hospitalization in Patients with Heart Failure and Depression The MOOD-HF Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA-J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2016, 315, 2683–2693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).