Microplastics and Nitrite Stress Affect Physiological and Metabolic Functions of the Hepatopancreas in Marine Shrimp

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals

2.2. Shrimp

2.3. Exposure Design and Sample Collection

2.4. Histopathological Analysis

2.5. Biochemical Assays

2.6. mRNA Expression Levels of Hepatopancreas

2.7. Metabolomics Analysis

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Morphological Changes

3.2. Changes in Oxidative Enzyme Activity in the Shrimp Hepatopancreas

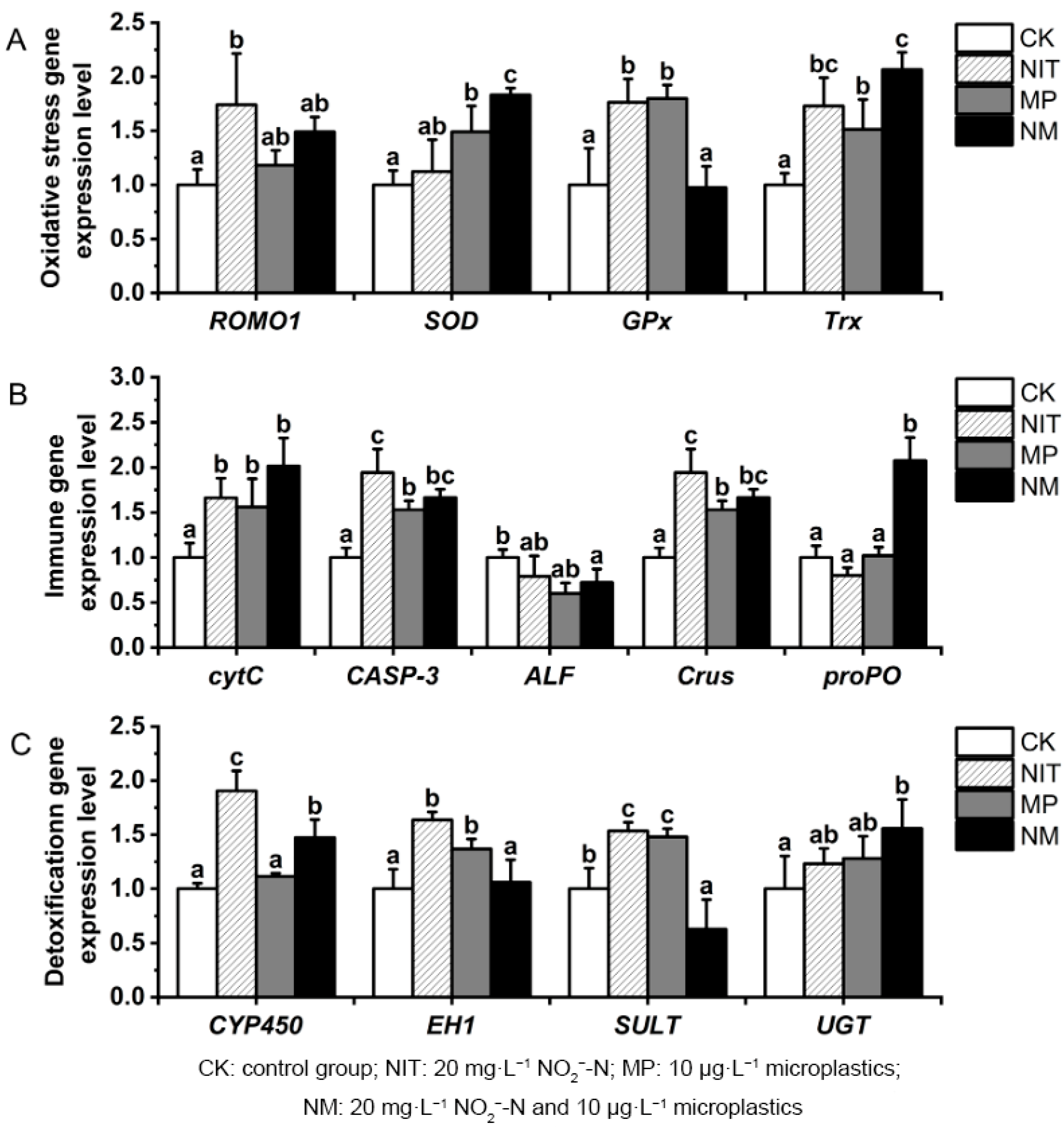

3.3. Changes in Antioxidant Gene Expression Level

3.4. Changes in Immune Gene Expression Level

3.5. Changes in Detoxification Metabolic Gene Expression Level

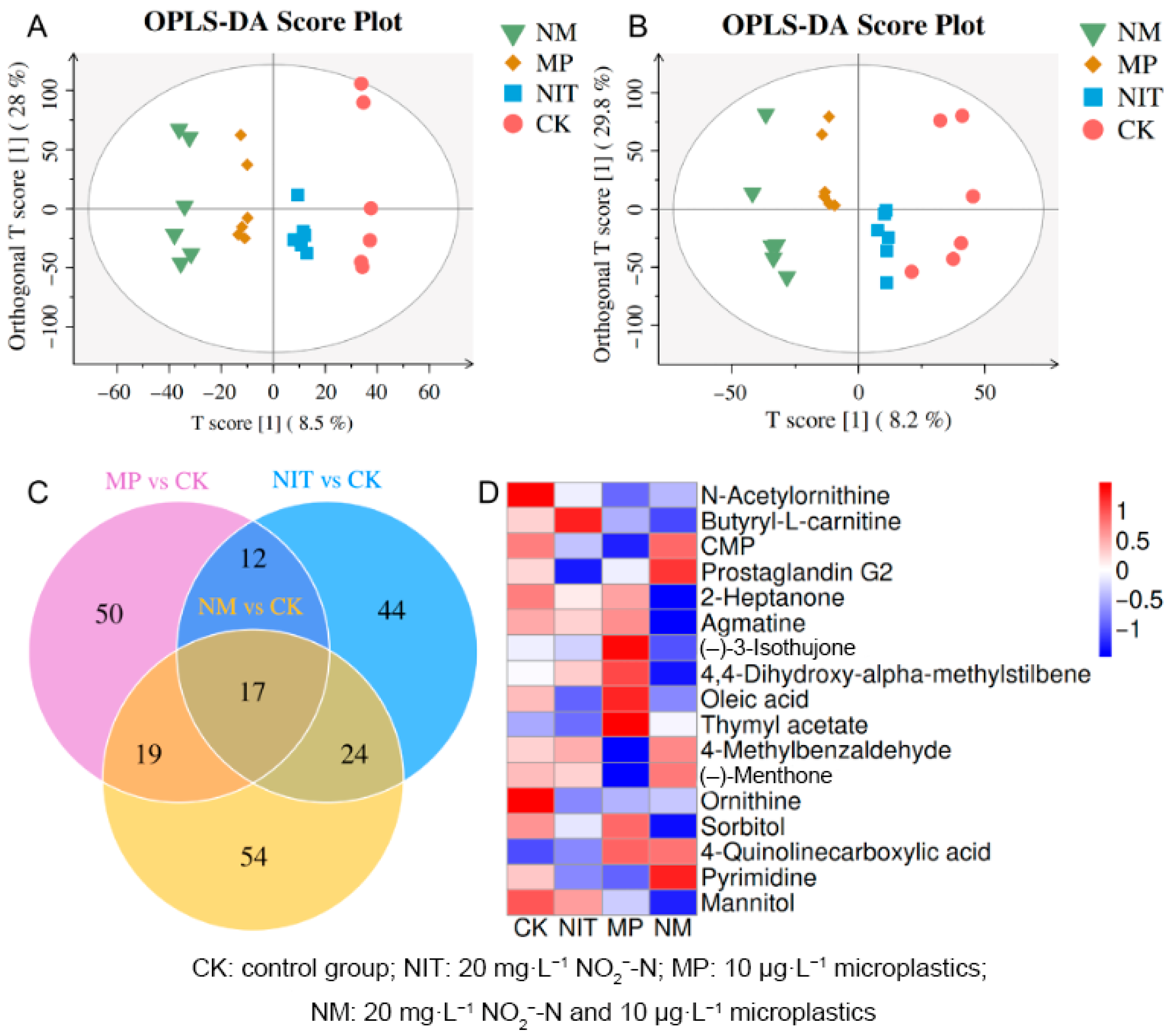

3.6. Metabolic Function Variations

3.6.1. Identification of Differential Metabolites

3.6.2. Functional Analysis of Differential Metabolites

3.6.3. Characteristics of Metabolite Markers

4. Discussion

4.1. Changes in Hepatopancreas Morphology in Response to Nitrite and Microplastics Exposure

4.2. Hepatopancreas Physiological Responses to Nitrite and Microplastics Exposure

4.3. Hepatopancreas Metabolic Response to Nitrite and Microplastics Exposure

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fajardo, C.; Martinez-Rodriguez, G.; Costas, B.; Mancera, J.M.; Fernandez-Boo, S.; Rodulfo, H.; De Donato, M. Shrimp immune response: A transcriptomic perspective. Rev. Aquac. 2022, 14, 1136–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisheries Department, Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Dong, H.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, X.; Zhang, J. Effect of dietary Clostridium butyricum on growth, intestine health status and resistance to ammonia stress in Pacific white shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2017, 65, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.L.; Ji, X.S.; Wang, X.P.; Li, T.M.; Wang, H.; Zeng, Q.F. Identification and characterization of differentially expressed genes in hepatopancreas of oriental river prawn Macrobrachium nipponense under nitrite stress. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2019, 87, 144–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugwu, K.; Herrera, A.; Gómez, M. Microplastics in marine biota: A review. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2021, 169, 112540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, V.G.; Nguyen, M.K.; Ngo, H.H.; Barceló, D.; Nguyen, H.L.; Um, M.J.; Nguyen, D.D. Microplastics in aquaculture environments: Current occurrence, adverse effects, ecological risk, and nature-based mitigation solutions. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2024, 209, 117168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Hu, L.; Tian, D.; Yu, Y.; Lu, L.; Zhang, J.; Huang, X.; Yan, M.; Chen, L.; Wu, Z.; et al. Toxicities of polystyrene microplastics (MPs) and hexabromocyclododecane (HBCD), alone or in combination, to the hepatopancreas of the whiteleg shrimp, Litopenaeus vannamei. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 329, 121646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Deng, B.; Kang, Z.; Araujo, P.; Mjøs, S.A.; Liu, R.; Lin, J.; Yang, T.; Qu, Y. Tissue accumulation of polystyrene microplastics causes oxidative stress, hepatopancreatic injury and metabolome alterations in Litopenaeus vannamei. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2023, 256, 114871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, N.; Zeng, C. Toxic effects of ammonia, nitrite, and nitrate to decapod crustaceans: A review on factors influencing their toxicity, physiological consequences, and coping mechanisms. Rev. Fish. Sci. 2013, 21, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sookruksawong, S.; Pongsomboon, S.; Tassanakajon, A. Genomic organization of the cytosolic manganese superoxide dismutase gene from the Pacific white shrimp, Litopenaeus vannamei, and its response to thermal stress. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2013, 35, 1395–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porter, A.; Godbold, J.A.; Lewis, C.N.; Savage, G.; Solan, M.; Galloway, T.S. Microplastic burden in marine benthic invertebrates depends on species traits and feeding ecology within biogeographical provinces. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 8023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gray, A.D.; Weinstein, J.E. Size- and shape-dependent effects of microplastic particles on adult daggerblade grass shrimp (Palaemonetes pugio). Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2017, 36, 3074–3080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Li, J.; Craig, N.J.; Su, L. Microplastic pollution in wild populations of decapod crustaceans: A review. Chemosphere 2022, 291, 132985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Y.; Zhu, X.; Duan, Y.; Huang, J.; Nan, Y.; Zhang, J. Toxic effects of nitrite and microplastics stress on histology, oxidative stress, and metabolic function in the gills of Pacific white shrimp, Litopenaeus vannamei. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2023, 187, 114531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moncrieffe, R.; Masry, M.; Cai, B.; Rossignol, S.; Kamari, A.; Poirier, L.; Bertrand, S.; Wong-Wah-Chung, P.; Zalouk-Vergnoux, A. Study of the ageing and the sorption of polyaromatic hydrocarbons as influencing factors on the effects of microplastics on blue mussel. Aquat. Toxicol. 2023, 262, 106669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, Y.; Zhang, J.; Huang, J.; Jiang, S. Effects of dietary Clostridium butyricum on the growth, digestive enzyme activity, antioxidant capacity, and resistance to nitrite stress of Penaeus monodon. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2019, 11, 938–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, Y.F.; Wang, Y.; Huang, J.H.; Li, H.; Dong, H.B.; Zhang, J.S. Toxic effects of cadmium and lead exposure on intestinal histology, oxidative stress response, and microbial community of Pacific white shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2021, 167, 112222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, S.L.; Wu, Y.C.; Xu, R.Q.; Chen, Y.T.; Chen, C.W.; Singhania, R.R.; Dong, C.D. Effect of polyethylene microplastics on oxidative stress and histopathology damages in Litopenaeus vannamei. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 288, 117800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Li, C.; Zheng, X. Toxic effects of polystyrene microplastics on the intestine of Amphioctopus fangsiao (Mollusca: Cephalopoda): From physiological responses to underlying molecular mechanisms. Chemosphere 2022, 308, 136362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.M.; Fu, B.; Li, Y.; Sun, J.; Xie, J.; Wang, G.; Tian, J.; Kaneko, G.; Yu, E. The effect of nitrite and nitrate treatment on growth performance, nutritional composition and flavor-associated metabolites of grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella). Aquaculture 2023, 562, 738784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Wang, M.; Wang, B.; Liu, M.; Jiang, K.; Wang, L. A comparative study on oxidative stress response in the hepatopancreas and midgut of the white shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei under gradual changes to low or high pH environment. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2018, 76, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.; Xiong, D.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Li, H.; Dong, H.; Zhang, J. Toxicological effects of microplastics in Litopenaeus vannamei as indicated by an integrated microbiome, proteomic and metabolomic approach. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 761, 143311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciji, A.; Akhtar, M.S. Nitrite implications and its management strategies in aquaculture: A review. Rev. Aquac. 2020, 12, 878–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochman, C.M.; Browne, M.A. Classify plastic waste as hazardous: Policies for managing plastic debris are outdated and threaten the health of people and wildlife. Nature 2013, 494, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.W.; Zhou, Q.; Yu, M.J.; Liu, Y.H.; Teng, X.H.; Gu, X.H. 4-tert-butylphenol triggers common carp hepatocytes ferroptosis via oxidative stress, iron overload, SLC7A11/GSH/GPX4 axis, and ATF4/HSPA5/GPX4 axis. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2022, 242, 113944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.; Su, Y.; Ma, H.; Deng, Y.; Feng, J.; Chen, X.; Jie, Y.; Guo, Z. Effect of nitrite exposure on oxidative stress, DNA damage and apoptosis in mud crab (Scylla paramamosain). Chemosphere 2020, 239, 124668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danial, N.N.; Korsmeyer, S.J. Cell death: Critical control points. Cell 2004, 116, 205–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, S.; Chen, J. Effects of nitrite exposure on the hemolymph electrolyte, respiratory protein and free amino acid levels and water content of Penaeus japonicus. Aquat. Toxicol. 1998, 44, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, H.; Huang, Y.; Li, S.; Weng, S.; Yu, X.; He, J. Characterization of a prophenoloxidase from hemocytes of the shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei that is down-regulated by white spot syndrome virus. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2008, 25, 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amparyup, P.; Kondo, H.; Hirono, I.; Aoki, T.; Tassanakajon, A. Molecular cloning, genomic organization and recombinant expression of a crustin-like antimicrobial peptide from black tiger shrimp Penaeus monodon. Mol. Immunol. 2008, 45, 1085–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Chung, C.; Lin, C.; Sung, H. Function of an anti-lipopolysaccharide factor (ALF) isoform isolated from the hemocytes of the giant freshwater prawn Macrobrachium rosenbergii in protecting against bacterial infection. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2014, 116, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, J.M.; Wolf, C.R.; Philpot, R.M. Interaction of 4-methylbenzaldehyde with rabbit pulmonary cytochrome P-450 in the intact animal, microsomes, and purified systems. Destructive and protective reactions. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1979, 28, 2031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatarinov, D.A.; Osipova, V.I.; Bogdanov, A.V.; Krivolapov, D.B.; Voloshina, A.D.; Mironov, V.F. ChemInform abstract: Synthesis of new 2-[2-(Dialkyl(diaryl)-phosphoryl)-2-methylpropyl] quinoline-4-carboxylic acids. Chem. Heterocycl. Compd. 2016, 47, 717–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, E.D.; Burwinkel, K.E.; Chava, A.K.; Notch, E.G.; Mayer, G.D. Activity of Phase I and Phase II enzymes of the benzo[a]pyrene transformation pathway in zebrafish (Danio rerio) following waterborne exposure to arsenite. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2010, 152, 371–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Topal, A.; Özdemir, S.; Arslan, H.; Çomaklı, S. How does elevated water temperature affect fish brain? (A neurophysiological and experimental study: Assessment of brain derived neurotrophic factor, cFOS, apoptotic genes, heat shock genes, ER-stress genes and oxidative stress genes). Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2021, 115, 198–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, B.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, N.; Deng, M.; Fang, Y. β-Asarone regulates ER stress and autophagy via inhibition of the PERK/CHOP/Bcl-2/Beclin-1 pathway in 6-OHDA-induced parkinsonian rats. Neurochem. Res. 2019, 44, 1159–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Ruan, L.; Shi, H. eIF2α of Litopenaeus vannamei involved in shrimp immune response to WSSV infection. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2014, 40, 609–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Figueiredo-Silva, A.C.; Corraze, G.; Kaushik, S.; Peleteiro, J.B.; Valente, L.M. Modulation of blackspot seabream (Pagellus bogaraveo) intermediary metabolic pathways by dispensable amino acids. Amino Acids 2010, 39, 1401–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szlas, A.; Kurek, J.M.; Krejpcio, Z. The Potential of L-arginine in prevention and treatment of disturbed carbohydrate and lipid metabolism-a review. Nutrients 2022, 14, 961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Zhang, X.; Xie, S.; Luo, J.; Zhu, T.; Yang, Y.; Li, X.; Huang, C.; Dang, Y.; Zhou, Q.; et al. Dietary phenylalanine level could improve growth performance, glucose metabolism and insulin and mTOR signaling pathways of juvenile swimming crabs, Portunus trituberculatus. Aquac. Rep. 2022, 27, 101395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, B.; Liu, H.; Tan, B.; Dong, X.; Chi, S.; Yang, Q.; Zhang, S. MHC II-PI 3 K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway regulates intestinal immune response induced by soy glycinin in hybrid grouper: Protective effects of sodium butyrate. Front. Immunol. 2021, 11, 601665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo, M.A.; Carretta, M.D.; Burgos, R.A. Long chain fatty acids as modulators of immune cells function: Contribution of FFA1 and FFA4 receptors. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 668330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutierrez, S.; Svahn, S.L.; Johansson, M.E. Effects of omega-3 fatty acids on immune cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 5028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucena, M.N.; Garçon, D.P.; Fontes, C.F.L.; Fabri, L.M.; Moraes, C.M.; McNamara, J.C.; Leone, F.A. Dopamine binding directly up-regulates (Na+, K+)-ATPase activity in the gills of the freshwater shrimp Macrobrachium amazonicum. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 2019, 233, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blantz, R.C.; Satriano, J.; Gabbai, F.; Kelly, C. Biological effects of arginine metabolites. Acta Physiol. Scand. 2000, 168, 21–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akram, M. Citric acid cycle and role of its intermediates in metabolism. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2014, 68, 475–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menzies, K.J.; Zhang, H.; Katsyuba, E.; Auwerx, J. Protein acetylation in metabolism—Metabolites and cofactors. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2016, 12, 43–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; YIN, Z.; WENG, S.; GUAN, H.; LI, S.; XING, K.; CHAN, S.; HE, J. Profiling of differentially expressed genes in hepatopancreas of white spot syndrome virus-resistant shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) by suppression subtractive hybridisation. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2007, 22, 520–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Han, M.; Rezaei, A.; Li, D.; Wu, G.; Ma, X. L-arginine modulates glucose and lipid metabolism in obesity and diabetes. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 2017, 18, 599–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizent, A. Oxidative stress-related metabolomic alterations in pregnancy: Evidence from exposure to air pollution, metals/metalloid, and tobacco smoke. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bogaert, J.J.; Favier, J.; Ghouzzi, V.E.; Djouadi, F.; Bénit, P.; Gimenez, A.P.; Rustin, P. Succinate dehydrogenase deficiency in human. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2005, 62, 2317–2324. [Google Scholar]

- Lv, L.; Xu, Z.; Zhao, M.; Gao, J.; Jiang, R.; Wang, Q.; Shi, X. Mannose inhibits Plasmodium parasite growth and cerebral malaria development via regulation of host immune responses. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 859228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obrosova, I.G.; Pacher, P.; Szab, C.; Zsengeller, Z.; Hirooka, H.; Stevens, M.J.; Yorek, M.A. Aldose reductase inhibition counteracts oxidative-nitrosative stress and poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase activation in tissue sites for diabetes complications. Diabetes 2005, 54, 234–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Meng, Q.; Wang, W.; Mo, D.; Dang, W.; Lu, H. Gut microbial composition and liver metabolite changes induced by ammonia stress in juveniles of an invasive freshwater Turtle. Biology 2022, 11, 1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Metabolites | Log2 Fold Change | Categories | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NIT vs. CK | MP vs. CK | NM vs. CK | ||

| Oleic acid | −2.54 | −3.15 | −2.85 | Lipid |

| Prostaglandin G2 | −2.78 | −2.46 | −5.20 | Lipid |

| Linoleic acid | 0 | −1.44 | 0 | Lipid |

| Palmitic acid | 1.28 | 0 | 0 | Lipid |

| Docosahexaenoic acid | 0 | 1.09 | 0 | Lipid |

| Docosapentaenoic acid | 0 | −2.36 | 0 | Lipid |

| L-Leucine | 0 | −2.72 | −1.13 | Amino acid |

| Agmatine | −0.89 | −0.71 | −0.6 | Amino acid |

| L-Arginine | 0 | 3.37 | 0.84 | Amino acid |

| L-Tyrosine | 0 | 1.39 | 2.8 | Amino acid |

| Ornithine | −1.55 | −1.45 | −2.87 | Amino acid |

| N-Acetylornithine | −1.95 | −1.38 | −2.74 | Amino acid |

| Glyceric acid | 0 | 1.26 | 0 | Carbohydrate |

| Citric acid | 0 | −1.46 | −1.63 | Carbohydrate |

| D-Mannose | 0 | 0.72 | 0 | Carbohydrate |

| Sorbitol | −2.24 | −2.04 | −2.41 | Carbohydrate |

| Fumaric acid | 0 | −1.56 | −1.41 | Carbohydrate |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Xing, Y.-F.; Zhu, X.-Y.; Dong, H.-B.; Huang, J.-H.; Duan, Y.-F.; Zhang, J.-S. Microplastics and Nitrite Stress Affect Physiological and Metabolic Functions of the Hepatopancreas in Marine Shrimp. J. Xenobiot. 2026, 16, 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/jox16010022

Xing Y-F, Zhu X-Y, Dong H-B, Huang J-H, Duan Y-F, Zhang J-S. Microplastics and Nitrite Stress Affect Physiological and Metabolic Functions of the Hepatopancreas in Marine Shrimp. Journal of Xenobiotics. 2026; 16(1):22. https://doi.org/10.3390/jox16010022

Chicago/Turabian StyleXing, Yi-Fu, Xuan-Yi Zhu, Hong-Biao Dong, Jian-Hua Huang, Ya-Fei Duan, and Jia-Song Zhang. 2026. "Microplastics and Nitrite Stress Affect Physiological and Metabolic Functions of the Hepatopancreas in Marine Shrimp" Journal of Xenobiotics 16, no. 1: 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/jox16010022

APA StyleXing, Y.-F., Zhu, X.-Y., Dong, H.-B., Huang, J.-H., Duan, Y.-F., & Zhang, J.-S. (2026). Microplastics and Nitrite Stress Affect Physiological and Metabolic Functions of the Hepatopancreas in Marine Shrimp. Journal of Xenobiotics, 16(1), 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/jox16010022