Mining Structural Information from Gas Chromatography-Electron-Impact Ionization-Mass Spectrometry Data for Analytical-Descriptor-Based Quantitative Structure–Activity Relationship

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Dataset and Preparation

2.2. Data Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

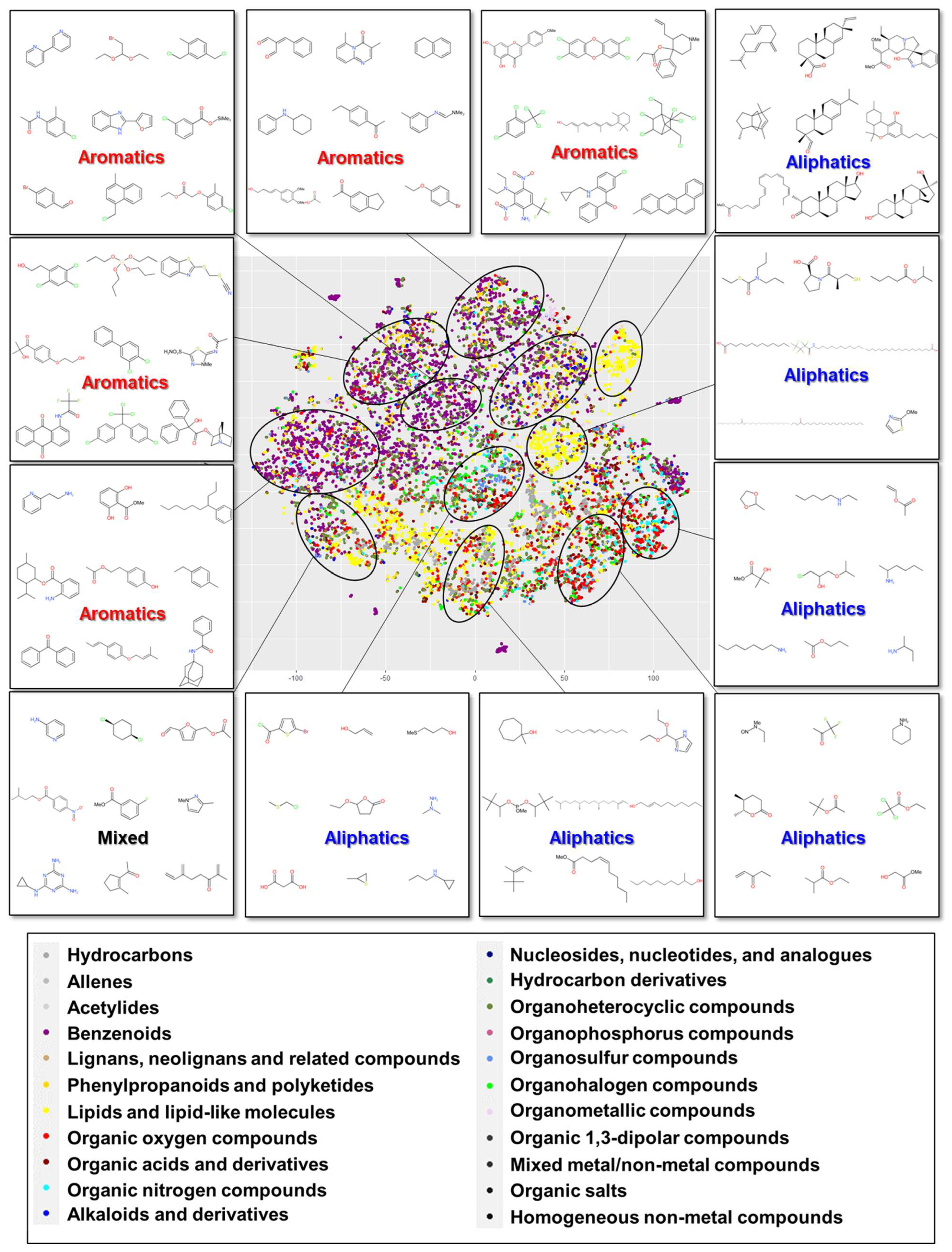

3.1. Relationship Between Chemical Class and Constructed Cluster

3.2. Model Performance Using Analytical and Molecular Descriptors

3.3. Influential Features for Prediction Based on Analytical Descriptor

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AD | Applicability domain |

| BP | Boiling point |

| CAS | Chemical Abstracts Service |

| Ko-w | Octanol-water partitioning coefficient |

| MAE | Mean absolute error |

| ML | Machine learning |

| MP | Melting point |

| Mw | Molecular weight |

| RI | Retention time index |

| RMSE | Root-mean-square error |

| SMILES | Simplified molecular input line entry system |

| WS | Water solubility |

References

- CAS. Available online: https://www.cas.org/ja/node/32521 (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- Reymond, J.-L. The Chemical Space Project. Acc. Chem. Res. 2015, 48, 722–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schymanski, E.L.; Singer, H.P.; Longrée, P.; Loos, M.; Ruff, M.; Stravs, M.A.; Vidal, C.R.; Hollender, J. Strategies to Characterize Polar Organic Contamination in Wastewater: Exploring the Capability of High Resolution Mass Spectrometry. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 48, 1811–1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zushi, Y.; Hashimoto, S.; Tanabe, K. Nontarget approach for environmental monitoring by GC × GC-HRTOFMS in the Tokyo Bay basin. Chemosphere 2016, 156, 398–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vermeulen, R.; Schymanski, E.L.; Barabási, A.-L.; Miller, G.W. The exposome and health: Where chemistry meets biology. Science 2020, 367, 392–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, J.; Ungeheuer, F.; Zheng, F.; Du, W.; Wang, Y.; Cai, J.; Zhou, Y.; Yan, C.; Liu, Y.; Kulmala, M.; et al. Nontarget Screening Exhibits a Seasonal Cycle of PM2.5 Organic Aerosol Composition in Beijing. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 7017–7028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peets, P.; Wang, W.-C.; MacLeod, M.; Breitholtz, M.; Martin, J.W.; Kruve, A. MS2Tox Machine Learning Tool for Predicting the Ecotoxicity of Unidentified Chemicals in Water by Nontarget LC-HRMS. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 15508–15517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, S.; Liu, G.; Zhang, J.; Yan, J.; Zhou, H.; Yan, X. Linking electron ionization mass spectra of organic chemicals to toxicity endpoints through machine learning and experimentation. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 431, 128558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zushi, Y. Direct Prediction of Physicochemical Properties and Toxicities of Chemicals from Analytical Descriptors by GC–MS. Anal. Chem. 2022, 94, 9149–9157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Detective-QSAR. Available online: http://www.mixture-platform.net/Detective_QSAR_Med_Open/ (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- Muratov, E.N.; Bajorath, J.; Sheridan, R.P.; Tetko, I.V.; Filimonov, D.; Poroikov, V.; Tropsha, A. QSAR without borders. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2020, 49, 3525–3564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Djoumbou Feunang, Y.; Eisner, R.; Knox, C.; Chepelev, L.; Hastings, J.; Owen, G.; Wishart, D.S. ClassyFire: Automated chemical classification with a comprehensive, computable taxonomy. J. Cheminformat. 2016, 8, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NIST. Available online: http://chemdata.nist.gov/dokuwiki/doku.php?id=chemdata:amdis (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- Horai, H.; Arita, M.; Kanaya, S.; Nihei, Y.; Ikeda, T.; Suwa, K.; Ojima, Y.; Tanaka, K.; Tanaka, S.; Aoshima, K.; et al. MassBank: A public repository for sharing mass spectral data for life sciences. J. Mass Spectrom. 2010, 45, 703–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MassBank. Available online: https://massbank.eu/MassBank/Search (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- Mona. Available online: https://mona.fiehnlab.ucdavis.edu/ (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- MS-DIAL. Available online: https://systemsomicslab.github.io/compms/msdial/main.html (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- CompTox. Available online: https://comptox.epa.gov/dashboard/ (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- ChemIDplus. Available online: https://chem.nlm.nih.gov/chemidplus/ (accessed on 1 February 2022).

- Mansouri, K.; Grulke, C.M.; Judson, R.S.; Williams, A.J. OPERA models for predicting physicochemical properties and environmental fate endpoints. J. Chemin. 2018, 10, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/ (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- Guha, R. Chemical Informatics Functionality in R. J. Stat. Softw. 2007, 18, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, T.; Gasteiger, J. (Eds.) Chemoinformatics: Basic Concepts and Methods; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Gortari, E.F.-D.; García-Jacas, C.R.; Martinez-Mayorga, K.; Medina-Franco, J.L. Database fingerprint (DFP): An approach to represent molecular databases. J. Cheminform. 2017, 9, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ClassyFire. Available online: http://classyfire.wishartlab.com/ (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- Maaten, L.V.D.; Hinton, G. Visualizing data using t-SNE. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2008, 9, 2579–2605. [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson, J. tsne: T-Distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding for R (t-SNE). 2022. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/tsne/tsne.pdf (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Chen, T.; Guestrin, C. XGBoost: A Scalable Tree Boosting System. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 August 2016; Association for Computing Machinery: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2016; pp. 785–794. [Google Scholar]

- Virtual Computational Chemistry Laboratory. Topological Descriptors. Available online: http://www.vcclab.org/lab/indexhlp/topodes.html (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- Nabi, D.; Gros, J.; Dimitriou-Christidis, P.; Arey, J.S. Mapping Environmental Partitioning Properties of Nonpolar Complex Mixtures by Use of GC × GC. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 6814–6826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orosz, Á.; Héberger, K.; Rácz, A. Comparison of Descriptor- and Fingerprint Sets in Machine Learning Models for ADME-Tox Targets. Front. Chem. 2022, 10, 852893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huber, F.; Ridder, L.; Verhoeven, S.; Spaaks, J.H.; Diblen, F.; Rogers, S.; van der Hooft, J.J.J. Spec2Vec: Improved mass spectral similarity scoring through learning of structural relationships. PLOS Comput. Biol. 2021, 17, e1008724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Detective-QSAR | Topological Descriptor | ECFP6 | MACCS Key | PubChem Fingerprint | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| log Mw | 0.041 | 0.005 | 0.052 | 0.060 | 0.037 |

| log Ko-w | 1.02 | 0.53 | 0.81 | 0.76 | 0.58 |

| BP | 23.5 | 21.2 | 42.9 | 39.0 | 26.8 |

| MP | 52.1 | 42.0 | 53.1 | 50.4 | 44.2 |

| log WS | 1.40 | 0.82 | 1.22 | 1.10 | 0.85 |

| log LD50 (rat, oral) | 0.72 | 0.61 | 0.65 | 0.60 | 0.56 |

| log LD50 (mouse, oral) | 0.67 | 0.55 | 0.58 | 0.55 | 0.55 |

| Detective-QSAR | Detective-QSAR (Without RI) | All-Six-Variable Model | maxint_mz | RI | center_mz | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| log Mw | 0.041 | 0.132 | 0.062 | 0.064 | 0.099 | 0.134 |

| log Ko-w | 1.02 | 0.95 | 1.48 | 1.55 | 1.75 | 1.59 |

| BP | 23.5 | 40.7 | 29.1 | 61.8 | 29.3 | 67.7 |

| MP | 52.1 | 56.9 | 61.3 | 79.6 | 65.6 | 76.5 |

| log WS | 1.40 | 1.26 | 1.68 | 1.84 | 2.03 | 1.76 |

| log LD50 (rat, oral) | 0.72 | 0.67 | 0.79 | 0.79 | 0.80 | 0.82 |

| log LD50 (mouse, oral) | 0.67 | 0.64 | 0.68 | 0.68 | 0.70 | 0.70 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zushi, Y. Mining Structural Information from Gas Chromatography-Electron-Impact Ionization-Mass Spectrometry Data for Analytical-Descriptor-Based Quantitative Structure–Activity Relationship. J. Xenobiot. 2025, 15, 177. https://doi.org/10.3390/jox15060177

Zushi Y. Mining Structural Information from Gas Chromatography-Electron-Impact Ionization-Mass Spectrometry Data for Analytical-Descriptor-Based Quantitative Structure–Activity Relationship. Journal of Xenobiotics. 2025; 15(6):177. https://doi.org/10.3390/jox15060177

Chicago/Turabian StyleZushi, Yasuyuki. 2025. "Mining Structural Information from Gas Chromatography-Electron-Impact Ionization-Mass Spectrometry Data for Analytical-Descriptor-Based Quantitative Structure–Activity Relationship" Journal of Xenobiotics 15, no. 6: 177. https://doi.org/10.3390/jox15060177

APA StyleZushi, Y. (2025). Mining Structural Information from Gas Chromatography-Electron-Impact Ionization-Mass Spectrometry Data for Analytical-Descriptor-Based Quantitative Structure–Activity Relationship. Journal of Xenobiotics, 15(6), 177. https://doi.org/10.3390/jox15060177