Abstract

Background: Beta-lactamase inhibitors (BLIs) are widely used with beta-lactam antibiotics to combat resistant infections, yet their safety profiles, especially for newer agents, remain underexplored. This study aimed to identify potential adverse event (AE) signals associated with BLIs using the USFDA Adverse Event Reporting System (USFDA AERS). Methods: The USFDA AERS was queried for AE reports involving FDA-approved BLIs from March 2004 to March 2024. After removing duplicates, only reports with BLIs listed as primary suspects were included. Disproportionality analysis was conducted using frequentist and Bayesian approaches, with statistical significance assessed by chi-square testing. Results: A total of 12,456 unique reports were analyzed. Common AEs across BLIs included hematologic disorders, hypersensitivity reactions, emergent infections, organ dysfunction, and neurological complications. Signal detection revealed specific associations: septic shock and respiratory failure with avibactam; lymphadenopathy and congenital anomalies with clavulanic acid; antimicrobial resistance and epilepsy with relebactam; disseminated intravascular coagulation and cardiac arrest with sulbactam; and agranulocytosis and conduction abnormalities with tazobactam. For vaborbactam, no distinct AE signals were identified apart from off-label use. Mortality was significantly more frequent with avibactam and relebactam (p < 0.0001). Conclusions: This analysis highlights a spectrum of AE signals with BLIs, including unexpected associations warranting further investigation. While some events may reflect comorbidities or concomitant therapies, these findings underscore the importance of continued pharmacovigilance and targeted clinical studies to clarify causality and ensure the safe use of BLIs in practice.

1. Introduction

Beta-lactam antimicrobials (penicillins, carbapenems, cephalosporins, and monobactams) constitute a vital class of antibiotics within the antimicrobial arsenal. These agents are widely preferred due to their broad antimicrobial spectrum, favorable safety profile, and tolerable adverse effects. However, the extensive use of β-lactam antibiotics has been observed to primarily drive the production of β-lactamases that hydrolyze the β-lactam ring, leading to the development of resistance amongst both Gram-positive and Gram-negative pathogens [1]. To date, sequence analysis has identified over 8200 distinct β-lactamase enzymes [2].

To combat this resistance, β-lactamase inhibitors (BLIs) have been developed and are commonly co-administered with β-lactam antibiotics to enhance their efficacy against drug-resistant infections. Currently, six BLIs, avibactam, clavulanic acid, relebactam, sulbactam, tazobactam, and vaborbactam, are approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration (USFDA) [3]. Clavulanic acid, sulbactam, and tazobactam were developed earlier and were initially effective against a limited range of β-lactamase enzymes. However, the rise of extended-spectrum β-lactamases and carbapenemases necessitated the development of novel BLIs such as avibactam, relebactam, and vaborbactam, which exhibit enhanced activity against these resistant strains [4]. These newer BLIs are particularly valuable in managing infections caused by multidrug-resistant Enterobacterales and Pseudomonas aeruginosa [5].

The first-generation BLIs, clavulanic acid, sulbactam, and tazobactam, are β-lactam-based molecules structurally related to penicillins; they act as “suicide substrates” by forming a covalent acyl-enzyme complex with serine β-lactamases [6]. In contrast, the more recently approved BLIs represent structural innovations designed to expand inhibitory activity. Avibactam and relebactam are diazabicyclooctane (DBO) derivatives, lacking the classical β-lactam core but instead possessing a bicyclic urea scaffold that provides reversible covalent inhibition of both class A and some class C and D β-lactamases [7]. Vaborbactam, on the other hand, belongs to the cyclic boronate class, with a boronic acid moiety that mimics the tetrahedral intermediate of β-lactam hydrolysis, conferring potent activity against class A carbapenemases, notably Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase (KPC) [8].

Interestingly, some BLIs exhibit weak intrinsic antibacterial activity against specific pathogens. Sulbactam, for example, is active against Acinetobacter spp., Neisseria gonorrhoeae, and Bacteroides spp.; clavulanic acid is effective against Haemophilus influenzae and Neisseria gonorrhoeae; and tazobactam shows activity against Borrelia burgdorferi [9,10,11].

Despite their widespread use, the adverse event profiles of BLIs are not comprehensively characterized. Reported adverse effects include gastrointestinal symptoms (nausea, constipation, and diarrhea), nervous system disorders (seizures and insomnia), altered platelet function, and hypersensitivity reactions, including anaphylaxis, Stevens–Johnson syndrome (SJS), toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN), and eosinophilia [12]. The USFDA Adverse Event Reporting System (AERS) collects spontaneously reported adverse events from healthcare professionals and is publicly accessible [13]. Disproportionality analysis of the USFDA AERS database has proven to be a valuable tool in identifying potential adverse event signals, warranting further exploration through clinical studies or mechanistic models [14].

However, there is a significant lack of literature on the adverse event profiles of BLIs, particularly the novel agents. A recent disproportionality analysis of the USFDA AERS database identified 654 reports associated with ceftolozane–tazobactam and 506 reports related to ceftazidime–avibactam, revealing signals of agranulocytosis and encephalopathy, respectively [15]. Beyond this, no prior study has systematically evaluated the adverse event signals across the entire spectrum of FDA-approved BLIs. Therefore, the novelty of our work lies in providing the first comprehensive pharmacovigilance assessment of both early- and recently approved BLIs using the FAERS database, thereby addressing an important gap in safety characterization.

2. Methods

2.1. Data Source

We queried the USFDA AERS database using the names of the USFDA-approved beta-lactamase inhibitors listed in Table 1 [16]. The data analyzed in this study encompassed 81 quarterly reports spanning March 2004 (the earliest publicly available USFDA AERS dataset) to March 2024 (the most recent complete dataset at the time of analysis).

Table 1.

USFDA approved beta-lactamase inhibitors.

2.2. Data Processing

Data processing followed the USFDA’s recommendations for the removal of duplicate reports [17]. Cases were identified using their unique case identification numbers, and for each case, only the entry with the highest individual safety report number was retained, with duplicate records removed. The USFDA categorizes the association between drugs and suspected adverse events into four categories: primary suspect, secondary suspect, interacting, or concomitant. For the purposes of this study, only unique reports in which a BLI was designated as the primary suspect were included, as this classification reflects the reporter’s assessment of the most likely causal drug and reduces confounding from concomitant therapies. From each unique report, data on gender, year of report, adverse events, and outcomes were extracted. Missing data points within the reports were excluded from further analysis.

2.3. Data Mining Algorithms

For this disproportionality analysis, we applied the case–non-case methodology to identify potential safety signals. In this approach, the frequency of specific adverse events reported with the drug of interest (“cases”) is compared against the frequency of the same events reported with all other drugs (“non-cases”) [18]. Signal detection was performed using the OpenVigil 2.1 platform, which incorporates both frequentist and Bayesian statistical methods.

Within the frequentist framework, the measures assessed included the reporting odds ratio (ROR) and the proportional reporting ratio (PRR) [19]. The ROR was expressed with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). A signal was considered statistically significant if it satisfied the following thresholds: a minimum of three independent case reports, PRR of at least 2, chi-square (χ2) value of 4 or greater, and a lower 95% CI bound for the ROR exceeding 1 [20].

For the Bayesian approach, the Bayesian Confidence Propagation Neural Network (BCPNN) and Multi-item Gamma Poisson Shrinker (MGPS) methods were applied to estimate signal detection measures. In BCPNN, signals were identified when the lower 95% CI limit of the information component (IC025) exceeded zero. In the Empirical Bayes geometric mean (EBGM) model, a signal was considered significant when the lower 95% CI limit of EBGM05 exceeded 2 [20].

The reported outcomes were categorized into one of the following: death, life-threatening events, or hospitalization (initial or prolonged).

2.4. Statistical Analysis

The demographic characteristics were described using descriptive statistics. Categorical variables were summarized as percentages. The chi-square (χ2) test was applied to evaluate the significance of differences in the distribution of reported outcomes. A p-value ≤ 0.05 was interpreted as statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA; Version 27.0, released 2020).

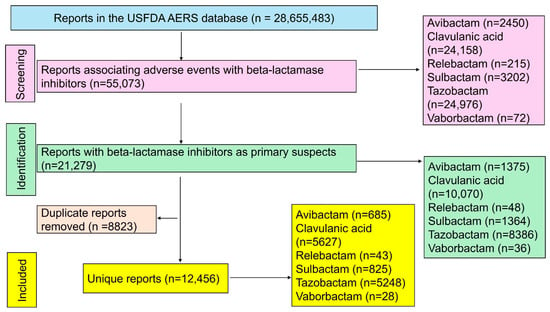

2.5. Search Results

Out of the 28,655,483 reports that were available in the USFDA AERS database, 12,456 unique reports were included in the final analysis (Figure 1). Clavulanic acid (n = 5627) and tazobactam (n = 5248) accounted for most reports, followed by other beta-lactamase inhibitors. The demographic characteristics of patients associated with each beta-lactamase inhibitor are summarized in Table 2. Excluding unreported data, most patients were elderly (>65 years) and predominantly male.

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram. A total of 12,456 unique reports were included in the final analysis.

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics of patients in the reports.

2.6. Signals Detected for Beta-Lactamase Inhibitors

Common adverse events identified across all beta-lactamase inhibitors included hematologic disorders such as myelosuppression, hemolysis, thrombocytopenia, neutropenia, eosinophilia, and hemolytic anemia. Hypersensitivity reactions, including anaphylaxis, drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS), Stevens–Johnson syndrome (SJS), and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN), were also observed, along with increased susceptibility to infections such as Clostridium difficile, Klebsiella, and Candida. Additional adverse events included organ dysfunction, particularly altered hepatic function, renal failure, and multiple organ dysfunction syndrome, as well as neurological disorders like encephalopathy, epilepsy, neurotoxicity, and delirium.

Specific adverse events associated with individual beta-lactamase inhibitors were as follows:

- Avibactam: Reported adverse events included eosinophilia, myelosuppression, death, septic shock, osteomyelitis, hyponatremia, neurotoxicity, encephalopathy, delirium, and respiratory failure (Table 3).

Table 3. Summary of signal detection measures for reports associated with avibactam.

Table 3. Summary of signal detection measures for reports associated with avibactam. - Clavulanic Acid: Associated with lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly, congenital anomalies, hypergammaglobulinemia, Kounis syndrome, mastoiditis, conjunctivitis, diarrhea, oral candidiasis, enterocolitis, megacolon, and serum-sickness-like reaction (Table 4).

Table 4. Summary of signal detection measures for reports associated with clavulanic acid.

Table 4. Summary of signal detection measures for reports associated with clavulanic acid. - Relebactam: Primarily showed signals of antimicrobial resistance and epilepsy (Table 5).

Table 5. Signal detection measures for adverse events reported with relebactam.

Table 5. Signal detection measures for adverse events reported with relebactam. - Sulbactam: Notable adverse events included disseminated intravascular coagulation, hemorrhagic diathesis, Kounis syndrome, cardiogenic shock, cardiac arrest, prolonged activated partial thromboplastin time, anaphylactic reaction, elevated creatine phosphokinase, and coagulopathy (Table 6).

Table 6. Signal detection measures for adverse events reported with sulbactam.

Table 6. Signal detection measures for adverse events reported with sulbactam. - Tazobactam: Specific adverse events included agranulocytosis, lymphohistiocytosis, prolonged prothrombin time, Evans syndrome, platelet dysfunction, cardiac conduction abnormalities, pulseless electrical activity, anaphylactic reaction, and perinatal complications (Table 7).

Table 7. Signal detection measures for adverse events with tazobactam.

Table 7. Signal detection measures for adverse events with tazobactam. - Vaborbactam: No specific adverse events were reported, apart from off-label use (Table 8).

Table 8. Signal detection measures for adverse events with vaborbactam.

Table 8. Signal detection measures for adverse events with vaborbactam.

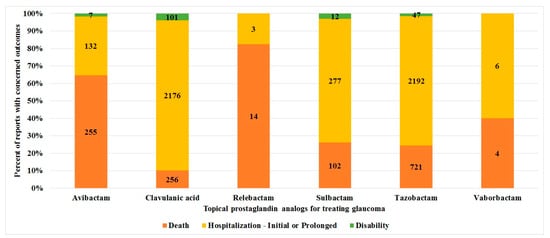

2.7. Comparison of Outcomes Between Adverse Events with Beta-Lactamase Inhibitors

The distribution of key outcomes among beta-lactamase inhibitors is presented in Figure 2. Death was reported more frequently with avibactam and relebactam compared to other inhibitors, with a statistically significant difference (p < 0.0001).

Figure 2.

Comparison of the reported outcomes between beta-lactamase inhibitors. The stacked bar chart depicts the distribution of key outcomes reported for each beta-lactamase inhibitor.

3. Discussion

3.1. Key Findings of This Study

Common adverse events reported for all beta-lactamase inhibitors included hematologic disorders (myelosuppression, hemolysis, thrombocytopenia), hypersensitivity reactions (anaphylaxis, DRESS, SJS, TEN), risk of emergent infections (Clostridium difficile, Klebsiella, Candida), organ dysfunction (hepatic, renal, multiple organ), and neurological issues (encephalopathy, epilepsy, delirium). Avibactam-specific events include septic shock and respiratory failure, while clavulanic acid shows lymphadenopathy, congenital anomalies, and enterocolitis. Relebactam is linked with antimicrobial resistance and epilepsy. Sulbactam shows disseminated intravascular coagulation and cardiac arrest, and tazobactam is associated with agranulocytosis and cardiac conduction abnormalities. Vaborbactam only reported off-label use.

3.2. Comparison with the Existing Literature

Among the adverse event signals identified in this study, hematologic reactions, including myelosuppression and hemolysis, were unexpected. However, these could be attributed to concomitant diseases or drugs causing myelotoxicity, particularly since tazobactam combinations are frequently used in patients with hematological malignancies [21]. Similarly, renal failure, hepatic failure, and multiple organ dysfunction, although unexpected, may result from underlying conditions such as sepsis or the use of other concurrent medications. Discontinuation of beta-lactam/BLI combinations due to organ failure has been previously reported [22]. The emergence of infections, particularly iatrogenic infections like Clostridium difficile, has also been documented with broad-spectrum β-lactam/BLIs [23]. Notably, the incidence of such infections appears higher with newer generations of cephalosporins and tetracyclines, whose usage has declined with the introduction of β-lactam/BLIs due to their comparable efficacy and spectrum [24].

Congenital anomalies associated with clavulanic acid use were identified as potential signals in this study. Clavulanic acid is commonly co-administered with amoxicillin, and epidemiological data have suggested an increased risk of cleft lip with/without cleft palate (odds ratio of 2), particularly when used in the last trimester of pregnancy (odds ratio of 4.3) [25]. However, a prospective, controlled study involving 191 pregnant women exposed to amoxicillin–clavulanic acid during the first trimester found no significant increase in the risk of major congenital malformations (1.9% with amoxicillin–clavulanic acid versus 3% in controls) [26]. Therefore, the association of clavulanic acid with congenital anomalies observed in this study is likely a false signal.

The adverse event patterns observed in this analysis can be interpreted in the context of the distinct chemical scaffolds and mechanisms of action of different BLIs. The classical β-lactam-based inhibitors such as clavulanic acid, sulbactam, and tazobactam share structural similarity with penicillins, which may explain the strong association with hypersensitivity reactions, cutaneous eruptions, and hepatic cholestasis seen in the disproportionality signals, reflecting immunoallergic pathways commonly linked to β-lactam cores. In contrast, the newer DBO derivatives, avibactam and relebactam, which lack a β-lactam ring, demonstrated signals of neurotoxicity, encephalopathy, epilepsy, and septic shock, which may be attributable to their broader β-lactamase binding spectrum and reversible covalent inhibition mechanism, raising the possibility of off-target interactions in neuronal or metabolic pathways. Vaborbactam, a cyclic boronate inhibitor, showed no distinct adverse event signals apart from off-label use, which may reflect its novel boronic-acid-based scaffold and limited clinical exposure to date [27]. Interestingly, signals of hematologic toxicity such as agranulocytosis with tazobactam and myelosuppression with avibactam further suggest potential structural contributions to bone marrow suppression. Similarly, the identification of congenital anomalies and lymphadenopathy with clavulanic acid could be linked to its β-lactam structural reactivity and potential immune-modulatory effects. Taken together, these findings highlight how the evolution of BLI structures, from β-lactam analogues to DBOs and cyclic boronates, may contribute to differing adverse event profiles, underlining the importance of considering both chemical class and mechanism of action when interpreting pharmacovigilance signals.

3.3. Strengths and Limitations

This study leverages a large dataset from the USFDA AERS, offering a comprehensive evaluation of adverse event signals associated with beta-lactamase inhibitors. A major strength of this analysis is the use of robust statistical methods, including frequentist and Bayesian approaches, which enhance the reliability of signal detection. However, the study has several limitations. First, the USFDA AERS is based on spontaneous reporting, which may be subject to underreporting, reporting biases, and incomplete data, potentially affecting the accuracy of the findings. Additionally, the study’s observational nature precludes establishing causality between the drugs and the adverse events. The lack of detailed clinical information in the reports, such as concomitant medications, underlying comorbidities, and dosing regimens, limits the ability to fully understand the context of the adverse events. Furthermore, novel BLIs such as vaborbactam had limited data due to their recent approval, restricting the analysis of adverse events associated with these newer agents.

Moving forward, prospective studies with more detailed clinical data and controlled settings are essential to validate these findings and establish causality. Expanding pharmacovigilance efforts and enhancing reporting accuracy through better healthcare provider awareness and electronic health record integration could provide more precise adverse event data. Additionally, mechanistic studies exploring the pathophysiology of unexpected adverse events, particularly hematologic and organ dysfunctions, are warranted to better understand the safety profile of BLIs and inform safer clinical use.

4. Conclusions

This study highlights a broad spectrum of adverse events associated with beta-lactamase inhibitors, including hematologic, hypersensitivity, infectious, organ dysfunction, and neurological disorders. While some adverse events are consistent with known safety profiles, unexpected signals such as myelosuppression, hemolysis, and organ dysfunction were also observed, warranting further investigation. The findings underscore the importance of continuous pharmacovigilance and signal detection to monitor the safety of both established and novel BLIs. Given the limitations of spontaneous reporting systems, future research should focus on prospective studies and mechanistic evaluations to better understand the causality and clinical implications of these adverse events. This knowledge is critical for optimizing the safe use of beta-lactamase inhibitors in clinical practice, particularly in populations with complex comorbidities.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.S.; methodology, K.S. and G.S.; software, K.S. and G.S.; validation, K.S.; formal analysis, K.S.; data curation, K.S. and G.S.; writing—original draft preparation, K.S.; writing—review and editing, K.S. and G.S.; visualization, K.S. and G.S.; supervision, K.S.; project administration, K.S. and G.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request, as the authors did not seek permission to publicly share them from the data owner.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Tooke, C.L.; Hinchliffe, P.; Bragginton, E.C.; Colenso, C.K.; Hirvonen, V.H.A.; Takebayashi, Y.; Spencer, J. β-Lactamases and β-Lactamase Inhibitors in the 21st Century. J. Mol. Biol. 2019, 431, 3472–3500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beta-Lactamase Database-Structure and Function. Available online: http://www.bldb.eu/ (accessed on 4 September 2024).

- Yahav, D.; Giske, C.G.; Grāmatniece, A.; Abodakpi, H.; Tam, V.H.; Leibovici, L. New β-Lactam-β-Lactamase Inhibitor Combinations. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2020, 34, e00115-20. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wong, D.; van Duin, D. Novel Beta-Lactamase Inhibitors: Unlocking Their Potential in Therapy. Drugs 2017, 77, 615–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sader, H.S.; Mendes, R.E.; Arends, S.R.; Carvalhaes, C.G.; Shortridge, D.; Castanheira, M. Comparative activity of newer β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitor combinations against Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from US medical centres (2020–2021). Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2023, 61, 106744. [Google Scholar]

- Bush, K.; Bradford, P.A. β-Lactams and β-Lactamase Inhibitors: An Overview. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2016, 6, a025247.1. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Wan, L.; Cen, X.; Tang, P.; Chen, F. Catalytic asymmetric total synthesis of diazabicyclooctane β-lactamase inhibitors avibactam and relebactam. Chem. Commun. 2022, 58, 10869–10872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pemberton, O.A.; Tsivkovski, R.; Totrov, M.; Lomovskaya, O.; Chen, Y. Structural Basis and Binding Kinetics of Vaborbactam in Class A β-Lactamase Inhibition. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2020, 64, e00398-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drawz, S.M.; Bonomo, R.A. Three decades of beta-lactamase inhibitors. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2010, 23, 160–201. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins, P.G.; Wisplinghoff, H.; Stefanik, D.; Seifert, H. In vitro activities of the beta-lactamase inhibitors clavulanic acid, sulbactam, and tazobactam alone or in combination with beta-lactams against epidemiologically characterized multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii strains. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2004, 48, 1586–1592. [Google Scholar]

- Levin, A.S. Multiresistant Acinetobacter infections: A role for sulbactam combinations in overcoming an emerging worldwide problem. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2002, 8, 144–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanna, N.R.; Gerriets, V. Beta-Lactamase Inhibitors; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2024. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557592/ (accessed on 27 June 2025).

- FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) Public Dashboard. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/questions-and-answers-fdas-adverse-event-reporting-system-faers/fda-adverse-event-reporting-system-faers-public-dashboard (accessed on 5 September 2024).

- Sridharan, K.; Sivaramakrishnan, G. A pharmacovigilance study assessing risk of angioedema with angiotensin receptor blockers using the US FDA Adverse Event Reporting System. Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 2024, 19, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gatti, M.; Raschi, E.; De Ponti, F. Serious adverse events with novel beta-lactam/beta-lactamase inhibitor combinations: A large-scale pharmacovigilance analysis. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2021, 40, 1169–1176. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Drugs@FDA: FDA-Approved Drugs. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/daf/index.cfm (accessed on 5 September 2024).

- Khaleel, M.A.; Khan, A.H.; Ghadzi, S.M.S.; Adnan, A.S.; Abdallah, Q.M. A Standardized Dataset of a Spontaneous Adverse Event Reporting System. Healthcare 2022, 10, 420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faillie, J.L. Case-non-case studies: Principle, methods, bias and interpretation. Therapie 2019, 74, 225–232. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, I.; Thiessard, F.; Miremont-Salamé, G.; Bégaud, B.; Tubert-Bitter, P. Pharmacovigilance data mining with methods based on false discovery rates: A comparative simulation study. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2010, 88, 492–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, G.; Jung, H.; Heo, S.J.; Jung, I. Comparison of Data Mining Methods for the Signal Detection of Adverse Drug Events with a Hierarchical Structure in Postmarketing Surveillance. Life 2020, 10, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaftari, A.M.; Hachem, R.; Malek, A.E.; Mulanovich, V.E.; Szvalb, A.D.; Jiang, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Ali, S.; Deeba, R.; Chaftari, P.; et al. A Prospective Randomized Study Comparing Ceftolozane/Tazobactam to Standard of Care in the Management of Neutropenia and Fever in Patients with Hematological Malignancies. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2022, 9, ofac079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Anglen, L.J.; Schroeder, C.P.; Couch, K.A. A Real-World Multicenter Outpatient Experience of Ceftolozane/Tazobactam. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2023, 10, ofad173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brink, A.; Coetzee, J.; Richards, G.; Feldman, C.; Lowman, W.; Tootla, H.; Miller, M.; Niehaus, A.; Wasserman, S.; Perovic, O.; et al. Best practices: Appropriate use of the new β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitor combinations, ceftazidime-avibactam and ceftolozane-tazobactam in South Africa. South. Afr. J. Infect. Dis. 2022, 37, 453. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, N.; Yuen, K.Y.; Kumana, C.R. Clinical role of beta-lactam/beta-lactamase inhibitor combinations. Drugs 2003, 63, 1511–1524. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, K.J.; Mitchell, A.A.; Yau, W.P.; Louik, C.; Hernández-Díaz, S. Maternal exposure to amoxicillin and the risk of oral clefts. Epidemiology 2012, 23, 699–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkovitch, M.; Diav-Citrin, O.; Greenberg, R.; Cohen, M.; Bulkowstein, M.; Shechtman, S.; Bortnik, O.; Arnon, J.; Ornoy, A. First-trimester exposure to amoxycillin/clavulanic acid: A prospective, controlled study. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2004, 58, 298–302. [Google Scholar]

- Novelli, A.; Del Giacomo, P.; Rossolini, G.M.; Tumbarello, M. Meropenem/vaborbactam: A next generation β-lactam β-lactamase inhibitor combination. Expert. Rev. Anti Infect. Ther. 2020, 18, 643–655. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).