Escape Room in Nursing Fundamentals Course: Students’ Opinions, Engagement, and Gameful Experience

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Design

3.2. Sample

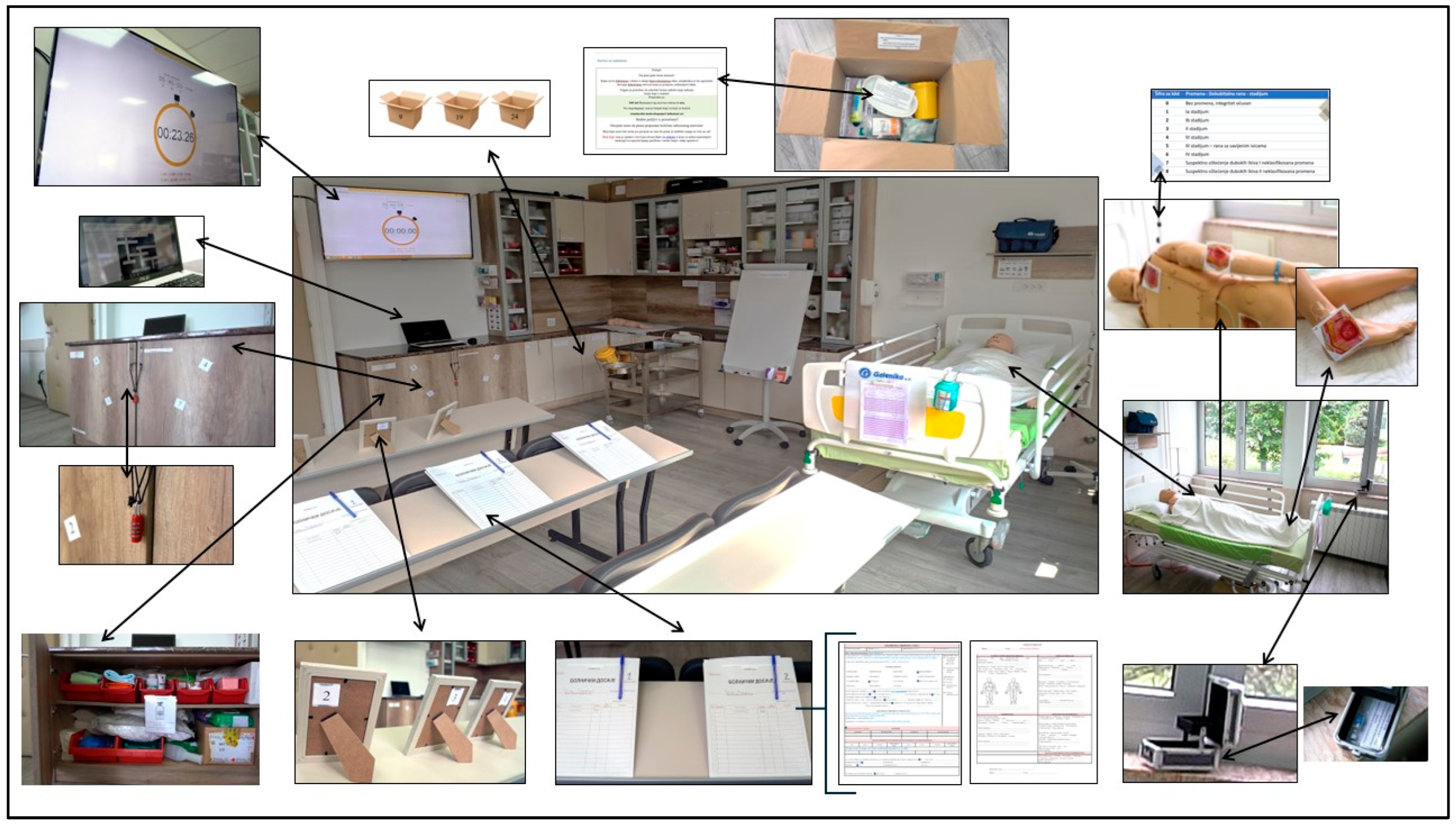

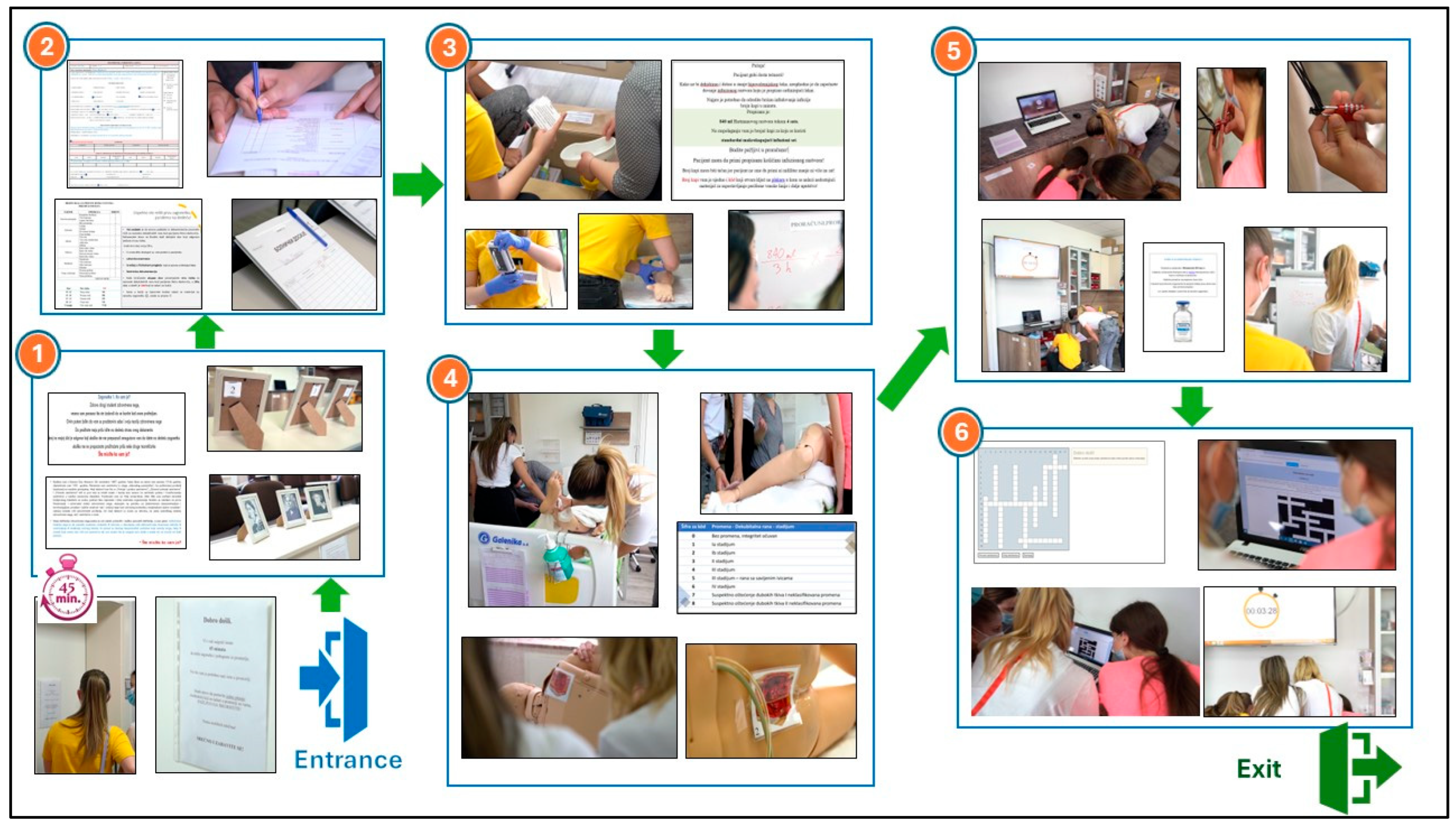

3.3. Development and Implementation of the Escape Room

3.3.1. Design and Rules

3.3.2. Implementation

3.4. Instruments and Data Collection Methods

3.5. Ethical Considerations

3.6. Statistical Data Processing

4. Results

4.1. Socio-Demographic Characteristics

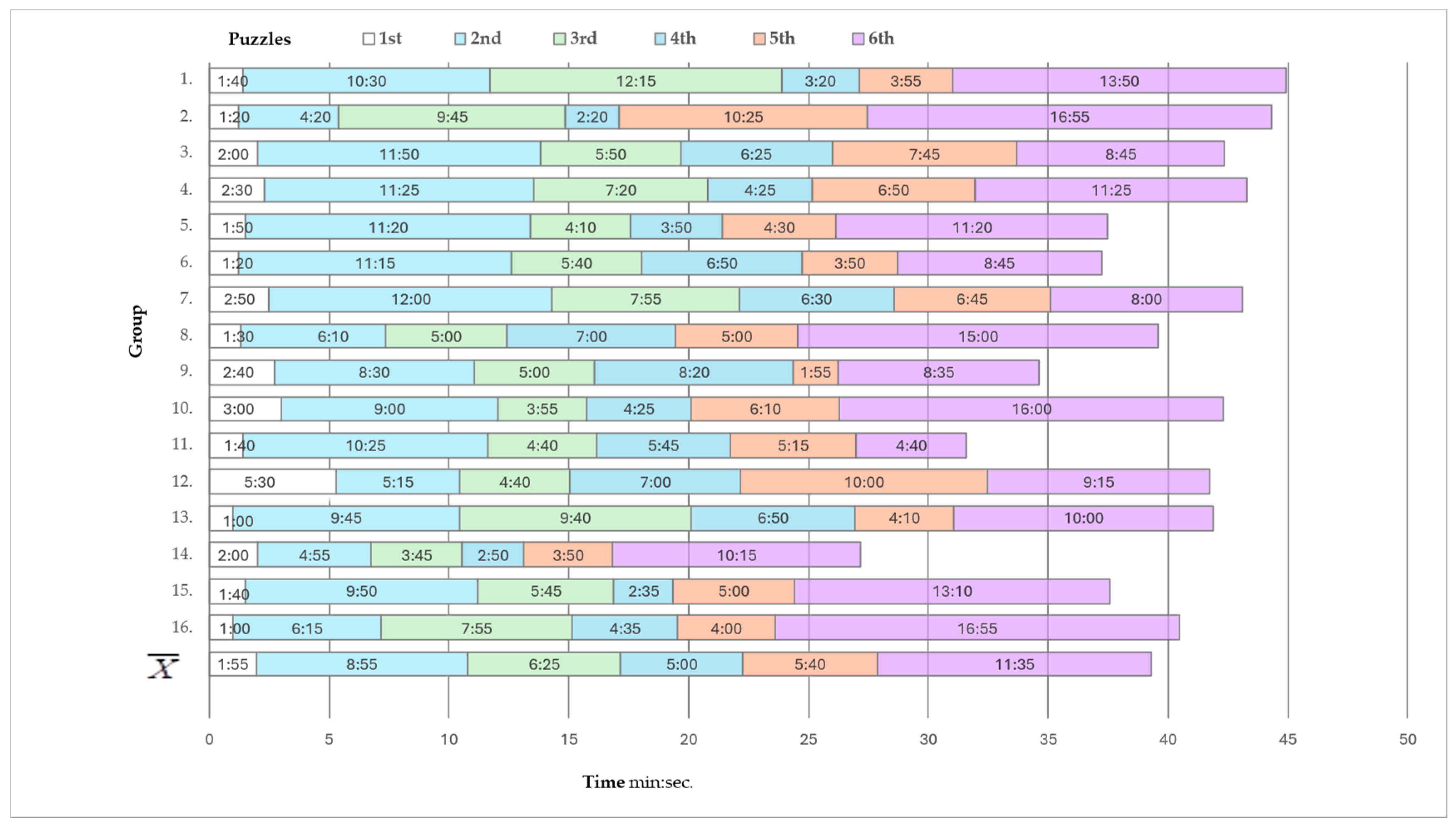

4.2. Playtime

4.3. Students’ Opinions About ER Learning Activities

4.4. Student Engagement Questionnaire

4.5. Gameful Experience Scale

4.6. Results for Standard Multiple Regression Analysis

5. Discussion

Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Public Involvement Statement

Guidelines and Standards Statement

Use of Artificial Intelligence

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ER | Escape Room |

| T&L | Teaching and learning |

| GBL | Game-based learning |

| GAMEX | Gameful Experience Scale |

| M | Mean values |

| SD | Standard deviation |

References

- Davis, K.; Lo, H.Y.; Lichliter, R.; Wallin, K.; Elegores, G.; Jacobson, S.; Doughty, C. Twelve tips for creating an escape room activity for medical education. Med. Teach. 2022, 44, 366–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anguas-Gracia, A.; Subirón-Valera, A.B.; Antón-Solanas, I.; Rodríguez-Roca, B.; Satústegui-Dordá, P.J.; Urcola-Pardo, F. An evaluation of undergraduate student nurses’ gameful experience while playing an escape room game as part of a community health nursing course. Nurse Educ. Today 2021, 103, 104948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubin, L. Using an escape activity in the classroom to enhance nursing student learning. Clin. Simul. Nurs. 2020, 47, 52–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, M.L.; Atanasio, L.L.M.; Medeiros, S.G.; Saraiva, C.O.P.O.; Santos, V.E.P. Evolution of nursing teaching in the use of education technology: A scoping review. Rev. Bras. Enferm. 2021, 21 (Suppl. 5), e20200422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Gaalen, A.E.J.; Brouwer, J.; Schönrock-Adema, J.; Bouwkamp-Timmer, T.; Jaarsma, A.D.C.; Georgiadis, J.R. Gamification of health professions education: A systematic review. Adv. Health Sci. Educ. Theory Pract. 2021, 26, 683–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuruca Ozdemir, E.; Dinc, L. Game-based learning in undergraduate nursing education: A systematic review of mixed-method studies. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2022, 62, 103375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEnroe-Petitte, D.; Farris, C. Using gaming as an active teaching strategy in nursing education. Teach. Learn. Nurs. 2020, 15, 61–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, V.; Burger, S.; Crawford, K.; Setter, R. Can You Escape? Creating an Escape Room to Facilitate Active Learning. J. Nurses Prof. Dev. 2018, 34, E1–E5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taraldsen, L.H.; Haara, F.O.; Lysne, M.S.; Jensen, P.R.; Jenssen, E.S. A review on use of escape rooms in education–touching the void. Educ. Inq. 2020, 13, 169–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veldkamp, A.; van de Grint, L.; Knippels, M.P.J.; van Joolingen, W.R. Escape education: A systematic review on escape rooms in education. Educ. Res. Rev.-Neth. 2020, 31, 100364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quek, L.H.; Tan, A.J.Q.; Sim, M.J.J.; Ignacio, J.; Harder, N.; Lamb, A.; Chua, W.L.; Lau, S.T.; Liaw, S.Y. Educational escape rooms for healthcare students: A systematic review. Nurse Educ. Today 2024, 132, 106004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-de la Torre, H.; Hernández-De Luis, M.-N.; Mies-Padilla, S.; Camacho-Bejarano, R.; Verdú-Soriano, J.; Rodríguez-Suárez, C.-A. Effectiveness of “Escape Room” Educational Technology in Nurses’ Education: A Systematic Review. Nurs. Rep. 2024, 14, 1193–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Brien, K.; Pitera, J. Gamifying instruction and engaging students with Breakout EDU. J. Educ. Technol. Syst. 2019, 48, 192–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reio, J.T.G.; Rocco, T.S.; Smith, D.H.; Chang, E. A critique of Kirkpatrick’s evaluation model. New Horiz. Adult Educ. 2017, 29, 35–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Lau, Y.; Cheng, L.J.; Lau, S.T. Learning experiences of game-based educational intervention in nursing students: A systematic mixed-studies review. Nurse Educ. Today 2021, 107, 105139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Puertas, L.; García-Viola, A.; Márquez-Hernández, V.V.; Garrido-Molina, J.M.; Granados-Gámez, G.; Aguilera-Manrique, G. Guess it (SVUAL): An app designed to help nursing students acquire and retain knowledge about basic and advanced life support techniques. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2021, 50, 102961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Urquiza, J.L.; Gómez-Salgado, J.; Albendín-García, L.; Correa-Rodríguez, M.; González-Jiménez, E.; Cañadas-De la Fuente, G.A. The impact on nursing students’ opinions and motivation of using a “Nursing Escape Room” as a teaching game: A descriptive study. Nurse Educ. Today 2019, 72, 73–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yosanovich, K. Improving Engagement and Collaboration Among Nursing Residents Through Escape Room Utilisation. Ph.D. Thesis, McKendree University, Lebanon, IL, USA, 2020. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/openview/ead25d15924e7770c05c2ae0060977a7/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750&diss=y (accessed on 25 March 2021).

- López-Belmonte, J.; Segura-Robles, A.; Fuentes-Cabrera, A.; Parra-González, M.E. Evaluating Activation and Absence of Negative Effect: Gamification and Escape Rooms for Learning. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2020, 17, 2224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wynn, L. Adapting the Escape Room to Engage Learners Two Ways During COVID-19. J. Diabetes Res. 2021, 3, 6–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powers, K.; Brandon, J.; Townsend-Chambers, C. Preparing nursing students for home health using an escape room: A qualitative study. Nurse Educ. Today 2022, 108, 105215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eukel, H.; Morrell, B. Ensuring educational escape-room success: The process of designing, piloting, evaluating, redesigning, and re-evaluating educational escape rooms. Simul. Gaming 2021, 52, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, D.R.; Gilson, R.L.; Harter, L.M. The psychological conditions of meaningfulness, safety and availability and the engagement of the human spirit at work. J. Occup. Organ. Psych. 2004, 77, 11–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eppmann, R.; Bekk, M.; Klein, K. Gameful experience in gamification: Construction and validation of a gameful experience scale [GAMEX]. J. Interact. Mark. 2018, 43, 98–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaton, D.E.; Bombardier, C.; Guillemin, F.; Ferraz, M.B. Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine 2000, 25, 3186–3191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, P.; Patel, N. ABC of face validity for questionnaire. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Rev. Res. 2020, 65, 164–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermanns, M.; Deal, B.; Campbell, A.; Hillhouse, S.; Opella, J.; Faigle, C.; Campbell, R. Using an “Escape Room” toolbox approach to enhance pharmacology education. J. Nurs. Educ. Pract. 2017, 8, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrue, M.; Suárez, N.; Ugartemendia-Yerobi, M.; Babarro, I. Let’s play and learn: Educational escape room to improve mental health knowledge in undergraduate nursing students. Nurse Educ. Today 2025, 144, 106453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krath, J.; Schürmann, L.; Von Korflesch, H.F. Revealing the theoretical basis of gamification: A systematic review and analysis of theory in research on gamification, serious games and game-based learning. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2021, 125, 106963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, N.; Darby, W.; Coronel, H. An escape room as a simulation teaching strategy. Clin. Simul. Nurs. 2019, 30, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-Torres, G.; Cardona, D.; Requena, M.; Rodriguez-Arrastia, M.; Roman, P.; Ropero-Padilla, C. The impact of using an “anatomy escape room” on nursing students: A comparative study. Nurse Educ. Today 2022, 109, 105205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wynn, L. An escape room simulation focused on renal-impairment for prelicensure nursing students. Teach. Learn. Nurs. 2021, 16, 95–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aktaş, N.; Baykara, Z.G.; Öztürk, D. The effect of education provided with the escape room game on nursing students’ learning of parenteral drug administration. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2024, 80, 104133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagundo-Rivera, J.; Romero-Castillo, R.; Garrido-Bueno, M.; Fernández-León, P. Innovative Methodologies in University Teaching: Pilot Experience of an Escape Room in Nursing Students. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Galiano, J.M.; Gonzalez-Cabrera, M.; Rodriguez-Almagro, J.; Hernández-Martínez, A. Evaluation of Knowledge and Competencies in Sexual and Reproductive Health Care Using an Escape Room with Scenario Simulations. Nurs. Rep. 2024, 14, 683–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Roca, B.; Calatayud, E.; Gomez-Soria, I.; Marcén-Román, Y.; Cuenca-Zaldivar, J.N.; Andrade-Gómez, E.; Subirón-Valera, A.B. Assessing health science students’ gaming experience: A cross-sectional study. Front. Educ. 2023, 8, 1258791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casler, K. Escape passive learning: 10 steps to building an escape room. J. Nurse Pract. 2022, 18, 569–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plass, J.L.; Homer, B.D.; Kinzer, C.K. Foundations of game-based learning. Educ. Psychol. 2015, 50, 258–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Pernas, S.; Gordillo, A.; Barra, E.; Quemada, J. Comparing face-to-face and remote educational escape rooms for learning programming. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 59270–59285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutledge, C.; Walsh, C.M.; Swinger, N.; Auerbach, M.; Castro, D.; Dewan, M.; Khattab, M.; Rake, A.; Harwayne-Gidansky, I.; Raymond, T.T.; et al. Gamification in Action: Theoretical and Practical Considerations for Medical Educators. Acad. Med. 2018, 93, 1014–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guckian, J.; Eveson, L.; May, H. The great escape? The rise of the escape room in medical education. Future Healthc. J. 2020, 7, 112–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampton, D.; Welsh, D.; Wiggins, A.T. Learning Preferences and Engagement Level of Generation Z Nursing Students. Nurse Educ. 2020, 45, 160–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrell, B.L.M.; Eukel, H.N. Escape the Generational Gap: A Cardiovascular Escape Room for Nursing Education. J. Nurs. Educ. 2020, 59, 111–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholson, S. Ask why: Creating a better player experience through environmental storytelling and consistency in escape room design. Meaningful Play 2016, 2016, 1–17. Available online: http://scottnicholson.com/pubs/askwhy.pdf (accessed on 17 July 2022).

- Monaghan, S.R.; Nicholson, S. Bringing escape room concepts to pathophysiology case studies. HAPS Educ. 2017, 21, 49–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Márquez-Hernández, V.V.; Garrido-Molina, J.M.; Gutiérrez-Puertas, L.; García-Viola, A.; Aguilera-Manrique, G.; Granados-Gámez, G. How to measure gamification experiences in nursing? Adaptation and validation of the Gameful Experience Scale [GAMEX]. Nurse Educ. Today 2019, 81, 34–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reed, J.M.; Ferdig, R.E. Gaming and anxiety in the nursing simulation lab: A pilot study of an escape room. J. Prof. Nurs. 2021, 37, 298–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ardenghi, S.; Luciani, M.; Rampoldi, G.; Ausili, D.; Bani, M.; Di Mauro, S.; Strepparava, M.G. Personal values among first-year medical and nursing students: A cross-sectional comparative study. Nurse Educ. Today 2021, 100, 104827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veldkamp, A.; Knippels, M.P.J.; van Joolingen, W.R. Beyond the early adopters: Escape rooms in science education. Front. Educ. 2021, 6, 622860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jambhekar, K.; Pahls, R.P.; Deloney, L.A. Benefits of an Escape Room as a Novel Educational Activity for Radiology Residents. Acad. Radiol. 2020, 27, 276–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullen, M.; Seiler, S.O. Escaping the Confines of Traditional Instruction: The Use of the Escape Room in a Transition to Practice Program. J. Nurses Prof. Dev. 2019, 35, 354–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Item | All Students | Gender | Prior Experience Playing Recreational ER | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | t | p | Yes | No | t | p | ||

| M ± SD | M ± SD | M ± SD | M ± SD | M ± SD | |||||

| Playing the game helped me learn the subject | 4.49 ± 0.53 | 4.80 ± 0.44 | 4.47 ± 0.53 | 1.575 | 0.176 | 4.50 ± 0.54 | 4.49 ± 0.53 | 0.037 | 0.971 |

| I enjoyed playing the game | 4.95 ± 0.27 | 5.00 ± 0.00 | 4.95 ± 0.28 | 0.387 | 0.700 | 5.00 ± 0.00 | 4.95 ± 0.28 | 0.428 | 0.670 |

| I think the game will help me in the exam | 4.32 ± 0.73 | 4.60 ± 0.54 | 4.30 ± 0.74 | 0.880 | 0.382 | 4.17 ± 0.75 | 4.34 ± 0.73 | 0.547 | 0.586 |

| I remembered and applied subject knowledge during the game | 4.68 ± 0.53 | 4.60 ± 0.54 | 4.68 ± 0.53 | 0.333 | 0.740 | 4.67 ± 0.51 | 4.68 ± 0.53 | 0.049 | 0.961 |

| There should be more games of this type in nursing studies | 4.86 ± 0.39 | 5.00 ± 0.00 | 4.85 ± 0.40 | 0.823 | 0.413 | 5.00 ± 0.00 | 4.85 ± 0.40 | 0.911 | 0.366 |

| The game has motivated me to study further, although the exam is still 6 weeks away | 4.37 ± 076 | 4.60 ± 0.54 | 4.35 ± 0.77 | 0.702 | 0.485 | 4.17 ± 0.75 | 4.39 ± 0.76 | 2.876 | 0.006 |

| Total | 4.64 ± 0.34 | 4.77 ± 0.19 | 4.62 ± 0.36 | 0.871 | 0.387 | 4.59 ± 0.21 | 4.64 ± 0.36 | 0.322 | 0.749 |

| Subscale | All Students | Gender | Prior Experience Playing Recreational ER | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | t | p | Yes | No | t | p | ||

| M ± SD | M ± SD | M ± SD | M ± SD | M ± SD | |||||

| Cognitive | 4.41 ± 0.30 | 4.50 ± 0.42 | 4.40 ± 0.42 | 0.496 | 0.62 | 4.44 ± 0.29 | 4.40 ± 0.42 | 0.208 | 0.836 |

| Emotional | 4.10 ± 0.49 | 4.10 ± 0.63 | 4.09 ± 0.48 | 0.018 | 0.986 | 4.00 ± 0.42 | 4.10 ± 0.5 | 0.504 | 0.60 |

| Physical | 4.22 ± 0.43 | 4.35 ± 0.38 | 4.21 ± 0.45 | 0.665 | 0.508 | 3.83 ± 0.44 | 4.26 ± 0.43 | 2.344 | 0.022 |

| Other | 4.55 ± 0.47 | 4.67 ± 0.46 | 4.54 ± 0.47 | 0.562 | 0.576 | 4.44 ± 0.54 | 4.56 ± 0.46 | 0.602 | 0.549 |

| Dimensions | All Students | Gender | Prior Experience Playing Recreational ER | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | t | p | Yes | No | t | p | ||

| M ± SD | M ± SD | M ± SD | M ± SD | M ± SD | |||||

| Enjoyment | 4.81 ± 0.89 | 4.93 ± 0.09 | 4.78 ± 0.40 | 2.327 | 0.029 | 4.86 ± 0.27 | 4.78 ± 0.40 | 0.456 | 0.650 |

| Absorption | 3.59 ± 0.98 | 3.90 ± 0.27 | 3.67 ± 1.04 | 0.493 | 2.624 | 3.89 ± 1.18 | 3.66 ± 1.00 | 0.516 | 0.607 |

| Creative thinking | 4.55 ± 0.88 | 4.60 ± 0.45 | 4.52 ± 0.59 | 0.305 | 0.761 | 4.54 ± 0.46 | 4.52 ± 0.60 | 0.081 | 0.935 |

| Activation | 3.21 ± 0.81 | 3.35 ± 0.57 | 3.31 ± 0.58 | 0.801 | 0.426 | 3.50 ± 0.94 | 3.11 ± 0.53 | 1.571 | 0.121 |

| Absence of negative affect | 1.23 ± 0.77 | 1.27 ± 0.36 | 1.25 ± 0.60 | 0.061 | 0.952 | 1.72 ± 1.47 | 1.20 ± 0.40 | 0.863 | 0.427 |

| Dominance | 2.73 ± 0.89 | 2.25 ± 0.66 | 2.73 ± 0.86 | 1.216 | 0.229 | 3.75 ± 0.95 | 3.53 ± 0.42 | 0.803 | 0.425 |

| Unstandardised Coefficient | Standardised Coefficient | t | p | Correlations Part | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ß | SE | Beta | ||||

| Constant | 8.013 | 2.789 | 2.873 | 0.006 | ||

| Cognitive engagement | 0.122 | 0.102 | 0.140 | 1.198 | 0.236 | 0.107 |

| Emotional engagement | 0.040 | 0.121 | 0.036 | 0.332 | 0.741 | 0.030 |

| Engagement—other | 0.156 | 0.175 | 0.099 | 0.891 | 0.377 | 0.080 |

| GAMEX—Enjoyment | 0.226 | 0.118 | 0.238 | 1.908 | 0.061 | 0.170 |

| GAMEX—Absorption | 0.009 | 0.040 | 0.026 | 0.232 | 0.818 | 0.021 |

| GAMEX—Creative Thinking | 0.384 | 0.119 | 0.408 | 3.214 | 0.002 | 0.287 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Simin, D.; Plećaš Đurić, A.; Aranđelović, B.; Živković, D.; Milutinović, D. Escape Room in Nursing Fundamentals Course: Students’ Opinions, Engagement, and Gameful Experience. Nurs. Rep. 2025, 15, 343. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15090343

Simin D, Plećaš Đurić A, Aranđelović B, Živković D, Milutinović D. Escape Room in Nursing Fundamentals Course: Students’ Opinions, Engagement, and Gameful Experience. Nursing Reports. 2025; 15(9):343. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15090343

Chicago/Turabian StyleSimin, Dragana, Aleksandra Plećaš Đurić, Branimirka Aranđelović, Dragana Živković, and Dragana Milutinović. 2025. "Escape Room in Nursing Fundamentals Course: Students’ Opinions, Engagement, and Gameful Experience" Nursing Reports 15, no. 9: 343. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15090343

APA StyleSimin, D., Plećaš Đurić, A., Aranđelović, B., Živković, D., & Milutinović, D. (2025). Escape Room in Nursing Fundamentals Course: Students’ Opinions, Engagement, and Gameful Experience. Nursing Reports, 15(9), 343. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15090343