Effectiveness of a Gamification-Based Intervention for Learning a Structured Handover System Among Undergraduate Nursing Students: A Quasi-Experimental Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Theoretical Framework

2.2. Gamification Approach

2.3. Sample

2.4. Scenario Context

2.5. Content Validity

2.6. Pre–Post Test

2.7. Procedure

2.8. Student Experience

2.9. Statistical Analysis

2.10. Ethical Considerations and Approvals

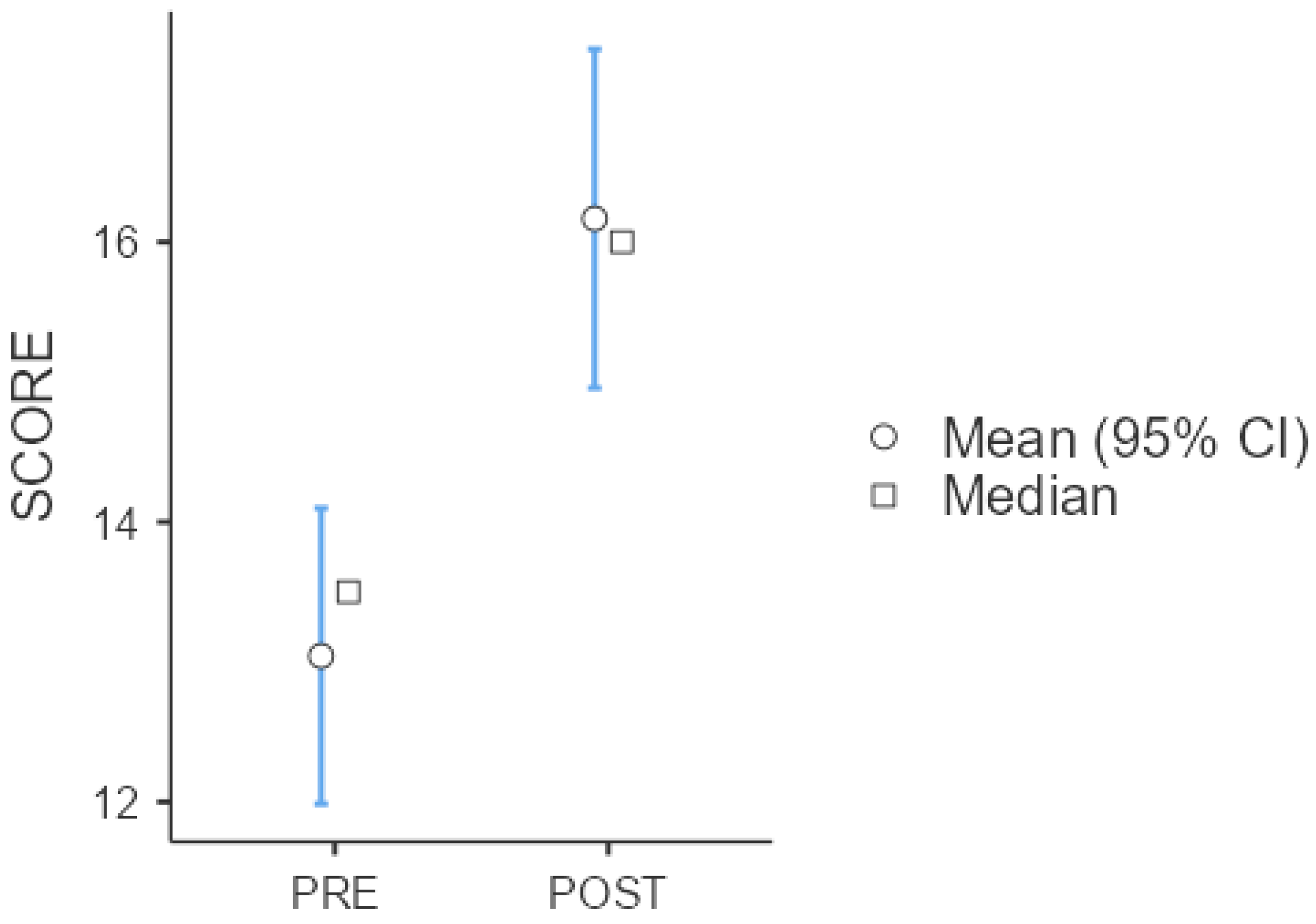

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Implications for Nursing Education and Research

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Public Involvement Statement

Guidelines and Standards Statement

Use of Artificial Intelligence

Abbreviations

| SG | Serious Game |

| SBAR | Situation, Background, Assessment, Recommendation |

| SDT | Self-Determination Theory |

| CLT | Cognitive Load Theory |

Appendix A. Test Sentences to Be Reorganized According to the SBAR Method (English Translation and Italian Original Version)

Appendix A.1. English Version

- Internal Medicine Case

- ☐

- During the ward round, the patient reports burning at the catheter insertion site.

- ☐

- Five days ago, Mr. Giovanni, 79 years old, presented to the Emergency Department (ED) accompanied by his son.

- ☐

- The patient has had arterial hypertension for 15 years and COPD for the past 4 years. Giovanni has smoked 20 cigarettes/day for 40 years.

- ☐

- Blood and catheter urine cultures were collected at 2:30 p.m. following a physician’s order.

- ☐

- Giovanni lives alone.

- ☐

- He arrived at the ED for dyspnea with SpO2 at 91% on room air and peripheral edema. Oxygen therapy was administered according to medical prescription.

- ☐

- Today, broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy was initiated (Amoxicillin and Clavulanic Acid).

- ☐

- At 3:00 p.m., the following vital signs were recorded: BP 130/75 mmHg, HR 98 bpm, SpO2 95% on oxygen therapy, no dyspnea at rest, RR 22/min, tympanic temperature consistently 38.5 °C.

- ☐

- Temperature should be monitored.

- ☐

- Admitted to the Internal Medicine Unit for acute heart failure.

- ☐

- Furosemide 20 mg IV was administered at 4:00 p.m.

- ☐

- Check the results of the culture tests.

- surgical case

- ☐

- One year ago, the patient was diagnosed with arterial hypertension, and seven years ago with type 2 diabetes mellitus. At home, she takes Amlodipine 5 mg and Metformin 500 mg.

- ☐

- At triage, she reported severe abdominal pain in the right iliac fossa, NRS 6/10.

- ☐

- Assess the need for enema administration.

- ☐

- Pain is currently under control, NRS 2/10.

- ☐

- Since admission to the ward, the patient has not had a bowel movement, including during the current shift.

- ☐

- The patient has a urinary catheter, which self-detached during the shift.

- ☐

- The surgical wound is clean and dry, with no signs of infection.

- ☐

- Mrs. Clara reports occasional nausea.

- ☐

- No known allergies.

- ☐

- Admitted to the Surgical Unit for laparoscopic appendectomy performed three days ago.

- ☐

- Reassess the surgical wound.

- ☐

- At 9:00 a.m., the following vital signs were recorded: BP 110/70 mmHg, HR 78 bpm, SpO2 97% on room air.

- ☐

- Mrs. Clara, 53 years old, presented to the ED accompanied by her husband.

- ☐

- Verify that the patient resumes spontaneous urination.

Appendix A.2. Italian Version

- Caso internistico:

- ☐

- Al giro visita l’assistito riferisce bruciore all’inserzione del catetere

- ☐

- Cinque giorni fa il signor Giovanni di 79 anni si presenta in PS accompagnato dal figlio

- ☐

- Da 15 anni il paziente soffre di ipertensione arteriosa e da 4 anni soffre di BPCO. Giovanni fuma 20 sigarette/die da 40 anni

- ☐

- Sono state eseguite emocolture ed urinocolture da catetere su prescrizione medica alle ore 14:30

- ☐

- Giovanni vive da solo.

- ☐

- Giunge in PS per dispnea con SpO2 91% in AA e edemi declivi. Si somministra O2tp come da prescrizione medica.

- ☐

- Oggi ha iniziato la terapia con antibiotico ad ampio spettro (Amoxicillina e Acido Clavulanico)

- ☐

- Alle ore 15:00 oggi presentava i seguenti PV: PA 130/75 mmHg, FC 98 bpm, SpO2 95% in O2tp, assenza di dispnea a riposo, FR 22 a/min, TC sempre 38.5 °C (timpanica).

- ☐

- Va monitorare la TC

- ☐

- Ricoverato nell’UO di Medicina Interna per scompenso cardiaco acuto

- ☐

- È stato somministrato Furosemide 20 mg EV h 16.00

- ☐

- Verificare l’esito degli esami colturali

- Caso Chirurgico

- ☐

- Un anno fa le è stata diagnosticata l’ipertensione arteriosa e 7 anni fa il DM2. Al domicilio l’assistita assume Amlodipina 5 mg e Metformina 500 mg

- ☐

- Al triage riferisce forti algie addominali in fossa iliaca destra, NRS 6/10

- ☐

- Valutare esecuzione di clistere

- ☐

- Dolore controllato, attualmente NRS 2/10

- ☐

- Dall’ingresso in reparto l’assistita non si è ancora scaricata, nemmeno durante il turno

- ☐

- L’assistita ha un CV che nel corso del turno si auto-rimuove

- ☐

- La ferita è pulita e asciutta, non è infetta

- ☐

- La signora Clara riferisce nausea occasionale

- ☐

- Non allergie note

- ☐

- Ricoverata nell’UO di Chirurgia per appendicectomia laparoscopica 3 giorni fa’

- ☐

- Rivalutare la ferita chirurgica

- ☐

- Alle ore 9:00 si rilevano i seguenti PV: 110/70 mmHg, 78 bpm, 97% AA

- ☐

- La signora Clara di 53 anni si presenta in PS accompagnata dal marito

- ☐

- Verificare che l’assistita riprenda ad urinare spontaneamente

References

- Malone, L.; Anderson, J.; Manning, J. Student participation in clinical handover—An integrative review. J. Clin. Nurs. 2016, 25, 575–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pronovost, P.J.; Thompson, D.A.; Holzmueller, C.G.; Lubomski, L.H.; Dorman, T.; Dickman, F.; Fahey, M.; Steinwachs, D.M.; Engineer, L.; Sexton, J.B.; et al. Toward learning from patient safety reporting systems. J. Crit. Care 2006, 21, 305–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suresh, G.; Horbar, J.D.; Plsek, P.; Gray, J.; Edwards, W.H.; Shiono, P.H.; Ursprung, R.; Nickerson, J.; Lucey, J.F.; Goldmann, D.; et al. Voluntary Anonymous Reporting of Medical Errors for Neonatal Intensive Care. Pediatrics 2004, 113, 1609–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations. Approved: Revisions to 2007 National Patient Safety Goals and Universal Protocol. Jt. Comm. Perspect. 2007, 27, 5–6. [Google Scholar]

- HealthGrades. Quality Study: Patient Safety in American Hospitals. Available online: https://www.providersedge.com/ehdocs/ehr_articles/Patient_Safety_in_American_Hospitals-2004.pdf (accessed on 12 April 2025).

- The Joint Commission International. Inadequate Hand-Off Communication. Sentinel Event Alert. 2017. Available online: www.jointcommission.org (accessed on 12 April 2025).

- McCloughen, A.; O’Brien, L.; Gillies, D.; McSherry, C. Nursing handover within mental health rehabilitation: An exploratory study of practice and perception. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2008, 17, 287–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janaway, B.; Zinchenko, R.; Anwar, L.; Wadlow, C.; Soda, E.; Cove, K. Using SBAR in psychiatry: Findings from two London hospitals. BJPsych Open 2021, 7 (Suppl. S1), S197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pazar, B.; Kavakli, O.; Ak, E.N.; Erten, E.E. Implementation and Evaluation of the SBAR Communication Model in Nursing Handover by Pediatric Surgery Nurses. J. Perianesth. Nurs. 2024, 39, 847–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galli, A.; Andreoli, E.; Pallua, F.Y.; Silvestri, I.; Manenti, A.; Dignani, L.; Contucci, S.; Menditto, V.G. Improvement of nursing handover in emergency department: A prospective observational cohort study. Discov. Health Syst. 2025, 4, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.N.; Kim, Y.; Im, Y.S. Educational Needs Assessment in Pediatric Nursing Handoff for Nursing Students. Child Health Nurs. Res. 2015, 21, 204–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; Kim, E.M.; Choi, Y.K.; Lee, H.Y.; Park, M.M.; Cho, E.Y.; Kim, E.S. An Exploration about Current Nursing Handover Practice in Korean Hospitals. J. Korean Clin. Nurs. Res. 2013, 19, 181–194. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, J.Y.; Byun, M.; Kim, E.J. Educational interventions for improving nursing shift handovers: A systematic review. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2024, 74, 103846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazzari, C. Implementing the Verbal and Electronic Handover in General and Psychiatric Nursing Using the Introduction, Situation, Background, Assessment, and Recommendation Framework: A Systematic Review. Iran. J. Nurs. Midwifery Res. 2024, 29, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abela-Dimech, F.; Vuksic, O. Improving the practice of handover for psychiatric inpatient nursing staff. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2018, 32, 729–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Meijel, B.; Van Der Gaag, M.; Kahn Sylvain, R.; Grypdonck, M.H.F. Recognition of early warning signs in patients with schizophrenia: A review of the literature. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2004, 13, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, G.E.; Marsden, R.; O’Connor, N. Clinical handover in acute psychiatric and community mental health settings. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2012, 19, 310–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Zou, G.; Zheng, M.; Chen, C.; Teng, W.; Lu, Q. Correlation between the quality of nursing handover, job satisfaction, and group cohesion among psychiatric nurses. BMC Nurs. 2022, 21, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz-Martos, S.; Álvarez-García, C.; Álvarez-Nieto, C.; López-Medina, I.M.; López-Franco, M.D.; Fernandez-Martinez, M.E.; Ortega-Donaire, L. Effectiveness of gamification in nursing degree education. PeerJ 2024, 12, e17167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nylén-Eriksen, M.; Stojiljkovic, M.; Lillekroken, D.; Lindeflaten, K.; Hessevaagbakke, E.; Flølo, T.N.; Hovland, O.J.; Solberg, A.M.S.; Hansen, S.; Bjørnnes, A.K.; et al. Game-thinking; utilizing serious games and gamification in nursing education—A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med. Educ. 2025, 25, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghafouri, R.; Zamanzadeh, V.; Nasiri, M. Comparison of education using the flipped class, gamification and gamification in the flipped learning environment on the performance of nursing students in a client health assessment: A randomized clinical trial. BMC Med. Educ. 2024, 24, 949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Pozo-Herce, P.; Tovar-Reinoso, A.; Carpintero-Blas, E.G.; Huertas, A.C.; de Viñaspre-Hernández, R.R.; Martínez-Sabater, A.; Chover-Sierra, E.; Rodríguez-García, M.; Juarez-Vela, R. Gamification as a Tool for Understanding Mental Disorders in Nursing Students: Qualitative Study. JMIR Nurs. 2025, 8, e71921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.S.; Chen, M.F.; Hwang, H.L.; Lee, B.O. Effectiveness of a nursing board games in psychiatric nursing course for undergraduate nursing students: An experimental design. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2023, 70, 103657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parozzi, M.; Terzoni, S.; Lomuscio, S.; Ferrara, P.; Destrebecq, A. Virtual Gamification in Mental Health Nursing Education: An In-Depth Scoping Review. In Methodologies and Intelligent Systems for Technology Enhanced Learning; Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 268–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreasen, E.M.; Berg, H.; Steinsbekk, A.; Høigaard, R.; Haraldstad, K. The effect of using desktop VR to practice preoperative handovers with the ISBAR approach: A randomized controlled trial. BMC Med. Educ. 2023, 23, 983. [Google Scholar]

- Streuber, S.; Saalfeld, P.; Podulski, K.; Hüttl, F.; Huber, T.; Buggenhagen, H.; Boedecker, C.; Preim, B.; Hansen, C. Training of patient handover in virtual reality. Curr. Dir. Biomed. Eng. 2020, 6, 20200040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elzeky, M.E.H.; Elhabashy, H.M.M.; Ali, W.G.M.; Allam, S.M.E. Effect of gamified flipped classroom on improving nursing students’ skills competency and learning motivation: A randomized controlled trial. BMC Nurs. 2022, 21, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karcı, H.D.; Bektaş Akpınar, N.; Özcan Yüce, U. Role-Play Based Gamification for Communication Skills and Nursing Competence in Internal Medicine Nursing. J. Nursology 2024, 27, 88–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolb, D.A. Experiential Learning. Experience as The Source of Learning and Development; Case Western Reserve University: Cleveland, OH, USA; Prentice Hall, Inc.: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. The “What” and “Why” of Goal Pursuits: Human Needs and the Self-Determination of Behavior. Psychol. Inq. 2000, 11, 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweller, J.; Ayres, P.; Kalyuga, S. Cognitive Load Theory; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commissione Tecnica Triage Regione Lombardia. Manuale di Triage Intraospedaliero Regione Lombardia. 2022. Available online: https://simeup.it/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/Allegato-1-Manuale-di-Triage.pdf (accessed on 9 October 2024).

- Polit, D.F.; Beck, C.T. The content validity index: Are you sure you know what’s being reported? Critique and recommendations. Res. Nurs. Health 2006, 29, 489–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verkuyl, M.; Djafarova, N.; Mastrilli, P.; Atack, L. Virtual Gaming Simulation: Evaluating Players’ Experiences. Clin. Simul. Nurs. 2022, 63, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abeele, V.V.; Spiel, K.; Nacke, L.; Johnson, D.; Gerling, K. Development and validation of the player experience inventory: A scale to measure player experiences at the level of functional and psychosocial consequences. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Stud. 2020, 135, 102370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Boore, J.R. Translation and back-translation in qualitative nursing research: Methodological review. J. Clin. Nurs. 2010, 19, 234–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanié, A.; Amorim, M.A.; Benhamou, D. Comparative value of a simulation by gaming and a traditional teaching method to improve clinical reasoning skills necessary to detect patient deterioration: A randomized study in nursing students. BMC Med. Educ. 2020, 53, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macwan, C.; Vidani, C.J.; Vidani, J. Exploring the Influence of Reels and Short Videos on the Reading and Listening Habits of Generation Z: A Comprehensive Study. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4889495 (accessed on 12 April 2025).

- Powers, K. Bringing simulation to the classroom using an unfolding video patient scenario: A quasi-experimental study to examine student satisfaction, self-confidence, and perceptions of simulation design. Nurse Educ. Today 2020, 86, 104324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aster, A.; Laupichler, M.C.; Zimmer, S.; Raupach, T. Game design elements of serious games in the education of medical and healthcare professions: A mixed-methods systematic review of underlying theories and teaching effectiveness. Adv. Health Sci. Educ. 2024, 29, 1825–1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erhel, S.; Jamet, E. Digital game-based learning: Impact of instructions and feedback on motivation and learning effectiveness. Comput. Educ. 2013, 67, 156–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grasse, K.M.; Kreminski, M.; Wardrip-Fruin, N.; Mateas, M.; Melcer, E.F. Using Self-Determination Theory to Explore Enjoyment of Educational Interactive Narrative Games: A Case Study of Academical. Front. Virtual Real. 2022, 3, 847120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Schmierbach, M.G.; Chung, M.Y.; Fraustino, J.D.; Dardis, F.; Ahern, L. Is it a sense of autonomy, control, or attachment? Exploring the effects of in-game customization on game enjoyment. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 48, 695–705. [Google Scholar]

- Yildirim, O.; Surer, E. Developing Adaptive Serious Games for Children with Specific Learning Difficulties: A Two-phase Usability and Technology Acceptance Study. JMIR Serious Games 2021, 9, e25997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benton, L.; Mavrikis, M.; Vasalou, A.; Joye, N.; Sumner, E.; Herbert, E.; Revesz, A.; Symvonis, A.; Raftopoulou, C. Designing for “challenge” in a large-scale adaptive literacy game for primary school children. Brit. J. Educ. Technol. 2021, 52, 1862–1880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinelli, C.V.; Nardacchione, G.; Trotta, E.; Di Fuccio, R.; Palladino, P.; Traetta, L.; Limone, P. The Effectiveness of Serious Games for Enhancing Literacy Skills in Children with Learning Disabilities or Difficulties: A Systematic Review. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 4512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vonthron, F.; Yuen, A.; Pellerin, H.; Cohen, D.; Grossard, C. A Serious Game to Train Rhythmic Abilities in Children with Dyslexia: Feasibility and Usability Study. JMIR Serious Games 2024, 12, e42733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, C.; Black, P.; Melby, V.; Fitzpatrick, B. The academic journey of students with specific learning difficulties undertaking pre-registration nursing programmes in the UK: A retrospective cohort study. Nurse Educ. Today 2022, 111, 105318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gender | |

| Female | 37 (77.1%) |

| Male | 10 (20.8%) |

| Prefer not to disclose | 1 (2.1%) |

| Age | |

| Mean (SD) | 23.2 (5.1) |

| Range | 19.0–49.0 |

| Missing | 1 |

| Repeater Student | |

| Yes | 30 (62.5%) |

| No | 18 (37.5%) |

| Nurse Assistant Qualification | |

| Yes | 2 (4.17%) |

| No | 46 (95.83%) |

| Attended Handover Lessons | |

| Yes | 31 (64.6%) |

| No | 17 (35.4%) |

| Group Descriptives | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | N | Mean | Median | SD | SE | |

| SCORE | PRE | 48 | 13 | 13.5 | 3.74 | 0.539 |

| POST | 48 | 16.2 | 16 | 4.28 | 0.618 | |

| Independent samples t-test | Statistic | Df | p | Effect Size | ||

| Student’s t | −3.81 | 94 | <0.001 | Cohen’s d | −0.78 | |

| Mann–Whitney U | 676 | <0.001 | Rank biserial correlation | 0.414 | ||

| DOMAIN | Item | Negative (%) | Neutral (%) | Positive (%) | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meaning | 1 | 2.45 | 19.5 | 78.05 | 1.71 | 1.23 |

| 2 | 0.00 | 9.8 | 90.24 | 2.12 | 0.98 | |

| 3 | 4.91 | 14.6 | 80.49 | 1.63 | 1.24 | |

| Curiosity | 4 | 12.15 | 9.8 | 78.05 | 1.29 | 1.42 |

| 5 | 9.73 | 4.9 | 85.37 | 1.37 | 1.36 | |

| 6 | 17.09 | 19.5 | 63.41 | 0.88 | 1.54 | |

| Mastery | 7 | 34.13 | 36.6 | 29.27 | −0.10 | 1.59 |

| 8 | 41.48 | 19.5 | 39.02 | −0.07 | 1.52 | |

| 9 | 53.69 | 26.8 | 19.51 | −0.66 | 1.51 | |

| Autonomy | 10 | 24.36 | 17.1 | 58.54 | 0.56 | 1.72 |

| 11 | 46.37 | 26.8 | 26.83 | −0.20 | 1.69 | |

| 12 | 36.57 | 36.6 | 26.83 | −0.17 | 1.69 | |

| Immersion | 13 | 43.86 | 9.8 | 46.34 | −0.12 | 2.05 |

| 14 | 19.51 | 12.2 | 68.29 | 0.90 | 1.77 | |

| 15 | 19.52 | 19.5 | 60.98 | 0.80 | 1.57 | |

| Progress Feedback | 16 | 12.23 | 14.6 | 73.17 | 1.37 | 1.48 |

| 17 | 12.15 | 9.8 | 78.05 | 1.37 | 1.3 | |

| 18 | 21.93 | 4.9 | 73.17 | 1.37 | 1.73 | |

| Audiovisual Appeal | 19 | 2.42 | 4.9 | 92.68 | 1.85 | 1.06 |

| 20 | 4.92 | 2.4 | 92.68 | 2.00 | 1.07 | |

| 21 | 2.40 | 9.8 | 87.80 | 1.90 | 1.16 | |

| Challenge | 22 | 2.40 | 9.8 | 87.80 | 1.61 | 1.05 |

| 23 | 4.85 | 17.1 | 78.05 | 1.22 | 1.11 | |

| 24 | 7.35 | 26.8 | 65.85 | 1.12 | 1.17 | |

| Ease of Control | 25 | 9.71 | 9.8 | 80.49 | 1.68 | 1.33 |

| 26 | 4.92 | 2.4 | 92.68 | 1.90 | 1.09 | |

| 27 | 2.43 | 12.2 | 85.37 | 1.88 | 1.08 | |

| Clarity of Goals | 28 | 2.42 | 4.9 | 92.68 | 2.29 | 0.87 |

| 29 | 2.46 | 7.3 | 90.24 | 2.07 | 1.01 | |

| 30 | 2.46 | 7.3 | 90.24 | 2.07 | 1.01 | |

| Enjoyment | 31 | 4.90 | 7.3 | 87.80 | 1.80 | 1.33 |

| 32 | 7.33 | 7.3 | 85.37 | 1.51 | 1.31 | |

| 33 | 7.27 | 9.8 | 82.93 | 1.56 | 1.38 |

| Survey Items (Constructs) | Video-Based SG [35] Score (SD) | This SG Score (SD) | Independent t-Test | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psychosocial consequences | ||||

| Playing the game was meaningful to me (Meaning) | 5.99 (1.32) | 5.71 (1.23) | 1.3175 | 0.1882 |

| I felt I was good at playing this game (Mastery) | 5.23 (1.45) | 3.9 (1.59) | 5.6346 | < 0.0001 |

| I was immersed in the game (Immersion) | 5.78 (1.39) | 4.9 (1.77) | 3.8372 | 0.0001 |

| I felt free to play the game in my own way (Autonomy) | 5.44 (1.65) | 4.76 (1.71) | 2.5423 | 0.0113 |

| I wanted to explore how the game evolved (Curiosity) | 5.70 (1.44) | 5.29 (1.41) | 1.7631 | 0.0784 |

| Functional consequences | ||||

| I thought the game was easy to control (Ease of Control) | 5.88 (1.42) | 5.88 (1.07) | 0 | 1 |

| The game was not too easy and not too hard to play (Challenge) | 5.46 (1.61) | 5.61 (1.04) | 0.5875 | 0.5571 |

| The game gave clear feedback on my progress towards the goals (Progress feedback) | 5.98 (1.31) | 5.37 (1.72) | 2.8132 | 0.0051 |

| I enjoyed the way the game was styled (Audiovisual appeal) | 6.02 (1.38) | 5.9 (1.15) | 0.5432 | 0.5872 |

| The goals of the game were clear to me (Goals and rules) | 6.11 (1.26) | 6.07 (1.1) | 0.1979 | 0.8432 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Parozzi, M.; Meraviglia, I.; Ferrara, P.; Morales Palomares, S.; Mancin, S.; Sguanci, M.; Lopane, D.; Destrebecq, A.; Lusignani, M.; Mezzalira, E.; et al. Effectiveness of a Gamification-Based Intervention for Learning a Structured Handover System Among Undergraduate Nursing Students: A Quasi-Experimental Study. Nurs. Rep. 2025, 15, 322. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15090322

Parozzi M, Meraviglia I, Ferrara P, Morales Palomares S, Mancin S, Sguanci M, Lopane D, Destrebecq A, Lusignani M, Mezzalira E, et al. Effectiveness of a Gamification-Based Intervention for Learning a Structured Handover System Among Undergraduate Nursing Students: A Quasi-Experimental Study. Nursing Reports. 2025; 15(9):322. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15090322

Chicago/Turabian StyleParozzi, Mauro, Irene Meraviglia, Paolo Ferrara, Sara Morales Palomares, Stefano Mancin, Marco Sguanci, Diego Lopane, Anne Destrebecq, Maura Lusignani, Elisabetta Mezzalira, and et al. 2025. "Effectiveness of a Gamification-Based Intervention for Learning a Structured Handover System Among Undergraduate Nursing Students: A Quasi-Experimental Study" Nursing Reports 15, no. 9: 322. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15090322

APA StyleParozzi, M., Meraviglia, I., Ferrara, P., Morales Palomares, S., Mancin, S., Sguanci, M., Lopane, D., Destrebecq, A., Lusignani, M., Mezzalira, E., Bonacaro, A., & Terzoni, S. (2025). Effectiveness of a Gamification-Based Intervention for Learning a Structured Handover System Among Undergraduate Nursing Students: A Quasi-Experimental Study. Nursing Reports, 15(9), 322. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15090322