Boosted Genomic Literacy in Nursing Students via Standardized-Patient Clinical Simulation: A Mixed-Methods Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Simulation Design

- -

- Nurse (acting as genetic counselor): Students practiced delivering genetic counseling to patients.

- -

- Patient: Students acted as patients receiving genetic counseling.

- -

- Observer: Students observed interactions, noting communication styles and clinical skills.

- -

- General briefing (30 min): A shared session introducing the methodology, objectives, structure, and content of the three clinical cases.

- -

- Three simulation stations, each structured as follows:

- ○

- Briefing (10 min) tailored to the specific scenario.

- ○

- Simulation (20 min) with standardized patients.

- ○

- Debriefing (30 min) focused on reflection and learning.

- -

- Transitions between scenarios (2 × 10 min = 20 min).

- -

- Mid-session break (30 min) to allow for rest and decompression.

- -

- Final meta-debriefing (40 min): A concluding group session to integrate the learning outcomes across all scenarios and roles.

2.4. Study Variables and Measurement Instruments

- -

- Knowledge Acquisition: This was evaluated through multiple-choice knowledge tests designed specifically for the course. Each test included 10 questions covering both theoretical and practical aspects of genetic counseling. These tests were administered immediately before (pre-simulation) and after (post-simulation) the simulation sessions to measure learning progression.

- -

- Communication Skills: These were assessed through qualitative analysis of students’ interactions during the simulation, as observed and recorded by facilitators. A thematic analysis was conducted using Atlas.ti 9 version 23 software, focusing on communication effectiveness, empathy, and clarity in delivering complex information. In addition, semi-structured interviews (see Appendix A Table A1) were carried out with a sample of participants to explore perceptions regarding their communication skill development.

- -

- Student Satisfaction: This was measured using the validated satisfaction questionnaire developed by Durá Ros [27], administered at the end of the simulation. The questionnaire uses a Likert scale ranging from 1 (very dissatisfied) to 5 (very satisfied) and evaluates simulation quality, learning usefulness, and perceived confidence improvement. The instrument is an adaptation of validated scales developed by Durá Ros and has demonstrated strong psychometric properties. In prior applications, the questionnaire achieved a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of α = 0.87, indicating high internal consistency and reliability in measuring student satisfaction with simulation-based learning.

2.5. Data Collection

2.6. Data Analysis

2.6.1. Quantitative Data Analysis

2.6.2. Qualitative Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Knowledge Acquisition

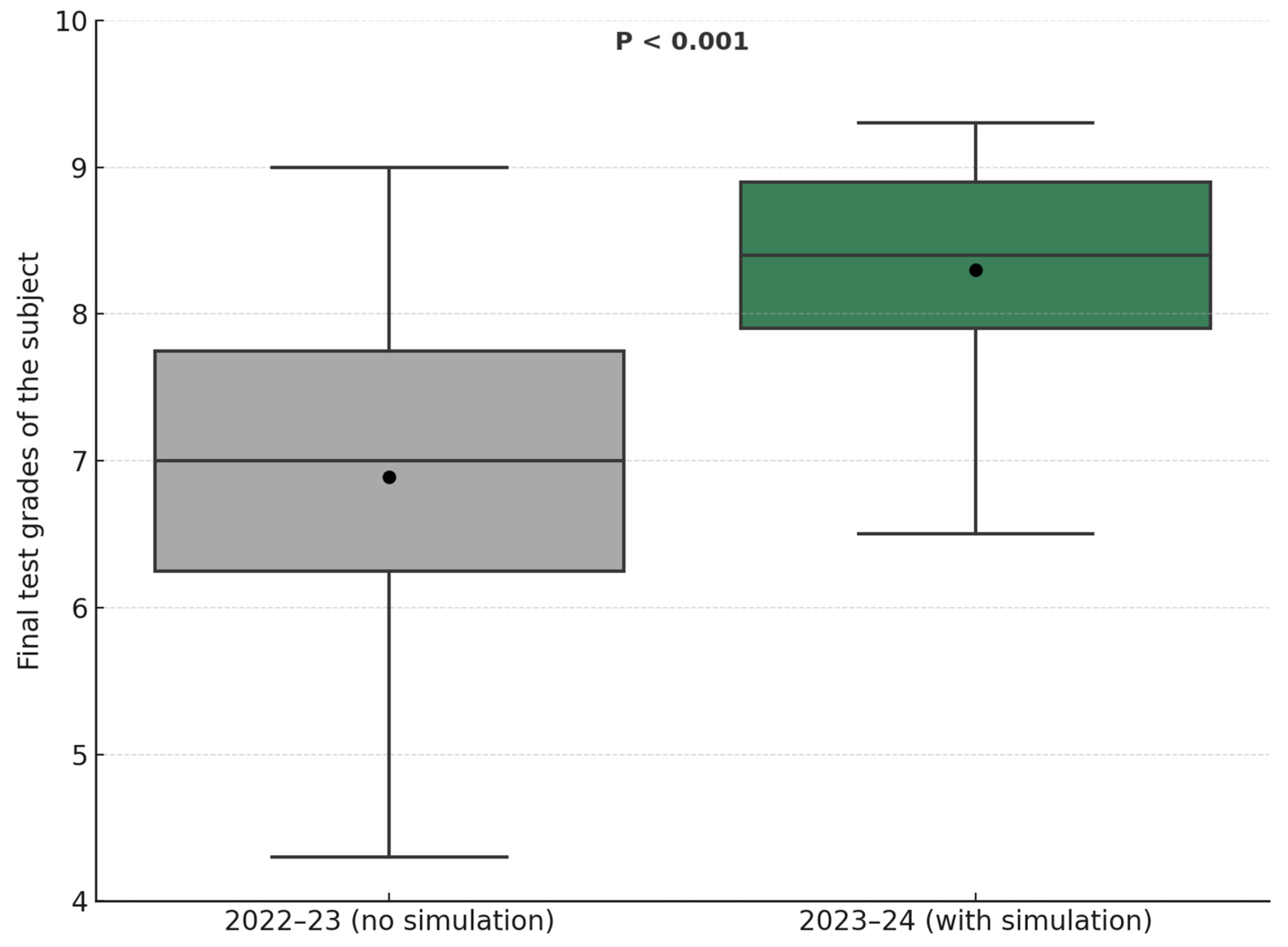

3.2. Final Course Grade Comparison

3.3. Student Satisfaction

3.4. Qualitative Analysis

4. Discussion

- -

- “Clinical simulation has allowed me to acquire solid theoretical genetic knowledge on different medical conditions”.

- -

- “It’s group learning that develops knowledge… I’ve also developed essential practical skills for my future nursing practice thanks to simulation”.

- -

- “Simulation has improved my ability to effectively diagnose genetic diseases”.

- -

- “It allows us to lose the fear of treating patients… helps us build confidence to gather information from the patient”.

- -

- “Simulation boosts my confidence in dealing with real patients as it familiarizes us with genetic counseling consultations”.

- -

- “Practice in simulation helps us overcome the fear of making mistakes… it makes us feel secure in multidisciplinary work”.

- -

- “Simulation helps us gain an idea and vision of what it’s like in reality”.

- -

- “Sometimes simulation practice does not align with theory”.

- -

- “Simulation practice doesn’t reflect reality”.

- -

- Direct experience from the patient’s perspective significantly improved students’ understanding and application of nursing care principles, fostering deeper empathy and holistic understanding of patient needs. Previous scientific evidence has described empathy as crucial in both observer and nurse roles, but not previously in the patient role [49].

- -

- The observer role provided students with opportunities to reflect on their own nursing practices and behaviors, identifying areas for improvement and strengthening critical self-assessment.

- -

- “Simulation is a valuable tool… I’ve improved the application of concepts in clinical practice, especially after being the patient and considering how I would better understand genetic counseling advice”.

- -

- “When observing peers during simulations, you think of many ways to lead the situation… whether they do it well or if there could be alternative diagnoses… which helps organize genetic counseling”.

- -

- “The experience as a patient in simulations provides a more comprehensive understanding of the clinical environment”.

- -

- “As a nursing student, when I played the patient role in simulations, it prompted me to consider issues I’ll have to address in the future that I hadn’t previously considered… it made me think differently… I enjoyed experiencing being both the patient and the nurse”.

- -

- “Acting as an observer in simulations has allowed me to develop critical and reflective skills crucial for my future as a nurse”.

- -

- “The observer role has enabled me to analyze genetic counseling objectively and reflect on it”.

Limitations

- Sample Size and Scope: Conducted with 30 students from a single institution, the sample limits generalizability. However, this size is appropriate for an exploratory design and was complemented by a mixed-methods approach to enhance internal validity.

- Non-Randomized Design: No randomized control group was included, limiting causal inference. Nonetheless, a quasi-experimental comparison was made with the previous academic year, offering a reasonable benchmark. The decision not to randomize was based on ethical and pedagogical considerations.

- Qualitative Sampling Bias: Interviews were conducted with students who had prior simulation experience, which may have biased responses positively. To mitigate this, data triangulation was used with field notes and observations from facilitators to broaden perspectives.

- Measurement and Bias Risk: Learning gains and satisfaction were assessed with validated knowledge tests and self-reported questionnaires, which may be subject to social-desirability or novelty effects; triangulation with qualitative data and historical-cohort comparison helped mitigate this risk. Because examination booklets were retrieved immediately after each sitting and a parallel-form test was applied to the 2023–2024 cohort, the likelihood of item contamination between academic years was greatly reduced, although informal sharing of questions cannot be completely ruled out. This potential test-transmission bias is therefore acknowledged when interpreting the grade comparison.

- Short-Term Assessment: Outcomes were evaluated immediately post-intervention, without long-term follow-up. Future studies should include delayed assessments to measure retention and application of skills in clinical practice.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Public Involvement Statement

Guidelines and Standards Statement

Use of Artificial Intelligence

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

Introduction and Context:

|

Appendix A.2

| Learning | The process by which individuals acquire and develop theoretical knowledge, practical skills, and the ability to establish and maintain therapeutic relationships and communicate effectively. This process involves assimilating information, actively practicing skills, and understanding the importance of human connection in therapeutic environments. |

| Attitudinal | Refers to the emotional and behavioral dispositions that healthcare professionals must demonstrate during simulated practice. This includes aspects such as motivation to learn, effective collaboration in teams, confidence in one’s abilities, empathetic communication, and the ability to manage stress. |

| Feedback | Evaluates the relevance, specificity, and usefulness of feedback provided by facilitators and peers during clinical simulation sessions, considering coherence between theory and clinical reality, as well as formative assessment. It includes aspects such as clarity of feedback, identification of areas for improvement, effectiveness in guiding learning, and the feedback’s ability to integrate theoretical concepts with simulated clinical practice, contributing to meaningful and constructive formative assessment of participant performance. |

| Role | Examine the participant’s ability to effectively perform the assigned role in clinical simulation, considering the impact of the different roles undertaken, empathy, and ethics. This involves assessing understanding of role-associated responsibilities, collaboration with other team members based on the role, and the ability to meet performance expectations corresponding to the assigned role, while maintaining an empathetic approach towards the simulated patient and making ethical decisions in simulated clinical situations. |

Appendix A.3

| Clinical Learning Dimensions in Simulation | Addresses the various dimensions of clinical learning during simulation sessions. Includes aspects related to the acquisition of theoretical knowledge and practical skills, the development of attitudes and competencies, as well as interaction with the simulated environment and effective communication. |

| Comprehensive Evaluation in Clinical Simulation | Encompasses the assessment of participant performance in clinical simulation, considering both the ability to perform assigned roles and the quality of feedback received. Includes aspects such as coherence between theory and clinical practice, the effectiveness of feedback in guiding learning, and the participant’s ability to maintain an empathetic and ethical approach during simulation sessions. |

Appendix A.4

| Dimensions | Metacategories | Category |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical Learning Dimensions in simulation | Learning | C1: Theoretical knowledge C2: Practical skills C3: Therapeutic relationship C4: Communication |

| Attitudinal | C5: Motivation C6: Teamwork C7: Self-confidence and self-efficacy | |

| Comprehensive Evaluation in Clinical Simulation | Feedback | C8: Consistency between theory and clinical reality C9: Formative assessment |

| Role | C10: Impact of different roles played C11: Empathy C12: Ethics |

References

- Eggert, J. Genetics and Genomics in Oncology Nursing: What Does Every Nurse Need to Know? Nurs. Clin. N. Am. 2017, 52, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.E. Nursing Curriculum. Lancet 1962, 278, 715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, J.F.; Prows, C.; Dimond, E.; Monsen, R.; Williams, J. Recommendations for educating nurses in genetics. J. Prof. Nurs. 2001, 17, 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martín Zurro, A. Prevención y promoción de la salud en las consultas de atención primaria: Apuntes sobre su pasado, presente y futuro. Aten. Primaria 2004, 33, 295–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Lea, D.H.; Lawson, M.T. A practice-based genetics curriculum for nurse educators: An innovative approach to integrating human genetics into nursing curricula. J. Nurs. Educ. 2000, 39, 418–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seibert, D.; Edwards, Q.T.; Maradiegue, A. Integrating genetics into advanced practice nursing curriculum: Strategies for success. Community Genet. 2007, 10, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Baraldes, E.; Ariza-Martin, K.; García-Gutiérrez, D.; García-Salido, C. Analysis of Nursing Education Curricula in Spain: Integration of Genetic and Genomic Concepts. Nurs. Rep. 2024, 14, 3689–3705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Salido, C.; Mateu Capell, M.; García Gutiérrez, D.; Ramírez-Baraldes, E. Perception of Knowledge Transfer from Clinical Simulations to the Care Practice in Nursing Students. Investig. Educ. Enferm. 2024, 42, e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adell-Lleixà, M.; Riba-Porquet, F.; Grau-Castell, L.; Sarrió-Colás, L.; Ginovart-Prieto, M.; Mulet-Aloras, E.; Reverté-Villarroya, S. Transforming Communication and Non-Technical Skills in Intermediate Care Nurses Through Ultra-Realistic Clinical Simulation: A Cross-Sectional Study. Nurs. Rep. 2025, 15, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vangone, I.; Caruso, R.; Magon, A.; Giamblanco, C.; Conte, G.; Baroni, I.; Russo, S.; Belloni, S.; Arrigoni, C. High-Fidelity Simulation and Its Impact on Non-Technical Skills Development Among Healthcare Professionals: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Acta Biomed. 2024, 95, e2024095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero, J.G.; Hafiz, A.H.; Eltohamy, N.A.E.; Gomma, N.; Al Jarrah, I. Repeated Exposure to High-Fidelity Simulation and Nursing Interns’ Clinical Performance: Impact on Practice Readiness. Clin. Simul. Nurs. 2021, 60, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshehri, F.D.; Jones, S.; Harrison, D. The Effectiveness of High-Fidelity Simulation on Undergraduate Nursing Students’ Clinical Reasoning-Related Skills: A Systematic Review. Nurse Educ. Today 2023, 121, 105679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanshaw, S.L.; Dickerson, S.S. High Fidelity Simulation Evaluation Studies in Nursing Education: A Review of the Literature. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2020, 46, 102818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar-Danesh, N.; Baxter, P.; Valaitis, R.K.; Stanyon, W.; Sproul, S. Nurse faculty perceptions of simulation use in nursing education. West. J. Nurs. Res. 2009, 31, 312–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, G.R.; Martínez, V.A.; Guerrero, X.M. La metodología de simulación en la enseñanza de los contenidos de parto y atención del recién nacido en enfermería. Rev. Cuba. Educ. Med. Super. 2017, 31, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Juguera Rodríguez, P.; Díaz Agea, J.L.; Pérez Lapuente, M.L.; Leal Costa, C.; Rojo Rojo, A.; Echevarría, P. La simulación clínica como herramienta pedagógica Percepción de los alumnos de Grado en Enfermería en la, UCAM. Enferm. Glob. Docencia-Investig. 2014, 33, 175–190. [Google Scholar]

- Lederman, L.C. Debriefing: Toward a Systematic Assessment of Theory and Practice. Simul. Gaming 1992, 23, 145–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maestre, J.M.; Szyld, D.; del Moral, I.; Ortiz, G.; Rudolph, J.W. The making of expert clinicians: Reflective practice. Rev. Clin. Esp. Engl. Ed. 2014, 214, 216–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller-Botti, S.; Maestre, J.M.; Del Moral, I.; Fey, M.; Simon, R. Linguistic validation of the debriefing assessment for simulation in healthcare in Spanish and cultural validation for 8 Spanish speaking countries. Simul. Healthc. 2021, 16, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudolph, J.W.; Simon, R.; Dufresne, R.L.; Raemer, D.B. There’s No Such Thing as ‘Nonjudgmental’ Debriefing: A Theory and Method for Debriefing with Good Judgment. Simul. Healthc. 2006, 14, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parviainen, A.; Halkoaho, A.; Maguire, J.; Mandysova, P.; Sund, R.; Vehviainen-Julkunen, K. Nursing students’ genomics literacy: Basis for genomics nursing education course development. Teach. Learn. Nurs. 2023, 18, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majstorović, D.; Barišić, A.; Štifanić, M.; Dobrača, I.; Vraneković, J. The Importance of Genomic Literacy and Education in Nursing. Front. Genet. 2021, 12, 759950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tashakkori, A.; Teddlie, C. Quality inferences in mixed methods research. In Advances in Mixed Methods Research: Theories and Applications; Bergman, M., Ed.; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2008; pp. 101–119. [Google Scholar]

- Gadamer, H.-G. El Giro Hermenéutico; Ediciones Cátedra Teorema: Madrid, Spain, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Maykut, P.; Morehouse, R. Investigación Cualitativa. Una Guía Práctica y Filosófica; Hurtado: Barcelona, Spain, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Van Manen, M. Investigación Educativa y Experiencia Vivida; Idea Books: Barcelona, Spain, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Durá Ros, M.J. La Simulación Clínica como Metodología de Aprendizaje y Adquisición de Competencias en Enfermería. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Madrid, Spain, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, B.G.; Strauss, A.L. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research; AldineTransaction: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, M.B.; Huberman, A.M.; Saldana, J. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook, 4th ed.; Sage: Chicago, IL, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Corbin, J.; Strauss, A.L. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory, 3rd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kalpokaite, N.; Radivojevic, I. Demystifying qualitative data analysis for novice qualitative researchers. Qual. Rep. 2019, 24, 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, G.; Alt-White, A.C.; Schaa, K.L.; Boyd, A.M.; Kasper, C.E. Genomics for Nursing Education and Practice: Measuring Competency. Worldviews Evid.-Based Nurs. 2015, 12, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayala, J.L.; Romero, L.E.; Alvarado, A.L.; Cuvi, G.S. La simulación clínica como estrategia de enseñanza-aprendizaje en ciencias de la salud. Metro Cienc. 2019, 27, 32–38. [Google Scholar]

- Rosario Fernández-Quiroga, M.; Yévenes, V.; Gómez, D.; Villarroel, E.; Rosario Fernández Quiroga, D.M. Use of clinical simulation as a learning strategy for the development of communication skills in medical students. Front. Eng. Manag. 2017, 20, 301–304. [Google Scholar]

- Dávila Cervantes, A. Simulación en Educación Médica. Investig. Educ. Med. 2014, 3, 100–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decker, S. Integrating guided reflection into simulated learning experiences. In Simulation in Nursing Education from Conceptualization to Evaluation; Jeffries, P.R., Ed.; National League for Nursing: Washington, DC, USA, 2007; pp. 89–102. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, D.; King, L. An integrative literature review on preparing nursing students through simulation to recognize and respond to the deteriorating patient. J. Adv. Nurs. 2013, 69, 2375–2388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foronda, C.; Liu, S.; Bauman, E.B. Evaluation of simulation in undergraduate nurse education: An integrative review. Clin. Simul. Nurs. 2013, 9, e409–e416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, F.; Passos-Neto, C.; Melro Braghiroli, O.F. Simulation in Medical Education: Brief history and methodology. Princ. Pract. Clin. Res. J. 2015, 1, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astudillo, Á.; López, M.Á.; Cadiz, V.; Fierro, J.; Figueroa, A.; Vilches, N. Validation of quality and satisfaction survey of clinical simulation in nursing students. Cienc. Enferm. 2017, 23, 133–145. [Google Scholar]

- Carvajal, N.; García, D.; Suárez, P.; Orozco, M.; Lozano, Y. Nivel de satisfacción de la simulación clínica en estudiantes de fisioterapia de una institución de educación superior de la ciudad de Cali-Colombia. Retos 2023, 48, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padilla, M.J.; González, J.; Sarmiento, F.; Tripoloni, D.; Cohen Arazi, L. Simulación clínica: Validación de encuesta de calidad y satisfacción en un grupo de estudiantes de Medicina. Rev. Esp Educ. Médica 2023, 5, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perdomo, A.; Díaz, L.; Cedeño, S.; Escalona, L.; Calderón, M. Satisfacción Estudiantil Sobre La Simulación Clínica Como Estrategia Didáctica En Enfermería. Rev. Enferm. Salud. 2022, 7, 36–42. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez, A.; Martinez, E.; Garza, G.; Rivera, C. Satisfacción en simulación clínica en estudiantes de medicina. Educ. Med. Super. 2021, 35, e2331. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez Maldonado, H.A.; Gallardo Casas, C.Á.; Pérez Elizondo, E. Satisfacción de la simulación clínica como herramienta pedagógica para el aprendizaje en estudiantes de pregrado en Enfermería. Med. Investig. Univ. Auton. Estado Mex. 2022, 10, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tortajada Lohaces, A.; García Molina, P.; Balaguer López, E.; Camaño Puig, R. Innovación educativa y simulación clínica en la docencia universitaria de Enfermería. Res. Technol. Best Pract. Educ. 2019, 2019, 134–142. [Google Scholar]

- Berndt, J. Patient safety and simulation in prelicensure nursing education: An integrative review. Teach. Learn. Nurs. 2014, 9, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, C.S. Impact of Training on Use of Debriefing for Meaningful Learning. Clin. Simul. Nurs. 2019, 32, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levett-Jones, T.; Bowen, L.; Ruhl, J.; Griffin, B.; Webb, D. Exploring Nursing Students’ Perspectives of a Novel Point-of-View Disability Simulation. Clin. Simul. Nurs. 2018, 18, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneidereith, T.; Daniels, A. Integration of Simulation to Prepare Adult-Gerontology Acute Care Nurse Practitioners. Clin. Simul. Nurs. 2019, 26, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilbanks, B.A.; McMullan, S.; Watts, P.I.; White, T.; Moss, J. Comparison of Video-Facilitated Reflective Practice and Faculty-Led Debriefings. Clin. Simul. Nurs. 2020, 42, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobbi, M.; Monger, E.; Weal, M.J.; McDonald, J.W.; Michaelides, D.; de Roure, D. The challenges of developing and evaluating complex care scenarios using simulation in nursing education. J. Res. Nurs. 2012, 17, 329–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tun, J.K.; Alinier, G.; Tang, J.; Kneebone, R.L. Redefining Simulation Fidelity for Healthcare Education. Simul. Gaming 2015, 46, 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bambini, D.; Washburn, J.; Perkins, R. Outcomes of Clinical Simulation for Novice Nursing Students: Communication, Confidence, Clinical Judgment. Nurs. Educ. Perspect. 2009, 30, 79–82. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Garcia-Gutiérrez, D.; Ramírez-Baraldes, E.; Orera, M.; Seidel, V.; Martínez, C.; García-Salido, C. Boosted Genomic Literacy in Nursing Students via Standardized-Patient Clinical Simulation: A Mixed-Methods Study. Nurs. Rep. 2025, 15, 297. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15080297

Garcia-Gutiérrez D, Ramírez-Baraldes E, Orera M, Seidel V, Martínez C, García-Salido C. Boosted Genomic Literacy in Nursing Students via Standardized-Patient Clinical Simulation: A Mixed-Methods Study. Nursing Reports. 2025; 15(8):297. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15080297

Chicago/Turabian StyleGarcia-Gutiérrez, Daniel, Estel·la Ramírez-Baraldes, Maria Orera, Verónica Seidel, Carmen Martínez, and Cristina García-Salido. 2025. "Boosted Genomic Literacy in Nursing Students via Standardized-Patient Clinical Simulation: A Mixed-Methods Study" Nursing Reports 15, no. 8: 297. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15080297

APA StyleGarcia-Gutiérrez, D., Ramírez-Baraldes, E., Orera, M., Seidel, V., Martínez, C., & García-Salido, C. (2025). Boosted Genomic Literacy in Nursing Students via Standardized-Patient Clinical Simulation: A Mixed-Methods Study. Nursing Reports, 15(8), 297. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15080297