The Association Between Missed Nursing Care and Job Satisfaction Among Nurses in Saudi Arabian Hospitals: A Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- To assess the prevalence of MNC;

- (2)

- To identify the reasons contributing to MNC;

- (3)

- To evaluate the level of job satisfaction among nurses;

- (4)

- To explore differences in missed nursing care and job satisfaction according to participant demographic and work-related characteristics;

- (5)

- To explore the association between MNC and job satisfaction.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

2.2. Study Population and Sampling

2.3. Data Collection Tools

2.3.1. Demographic and Work-Related Data

2.3.2. Missed Nursing Care (MNC) Scale

2.3.3. Job Satisfaction Scale

2.4. Data Collection Procedure

2.5. Ethical Considerations

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic Characteristics of the Participants

3.2. Reasons for Missed Nursing Care

3.3. Distribution of Job Satisfaction Levels Among Participants

3.4. Differences in Missed Nursing Care and Job Satisfaction by Participant Characteristics

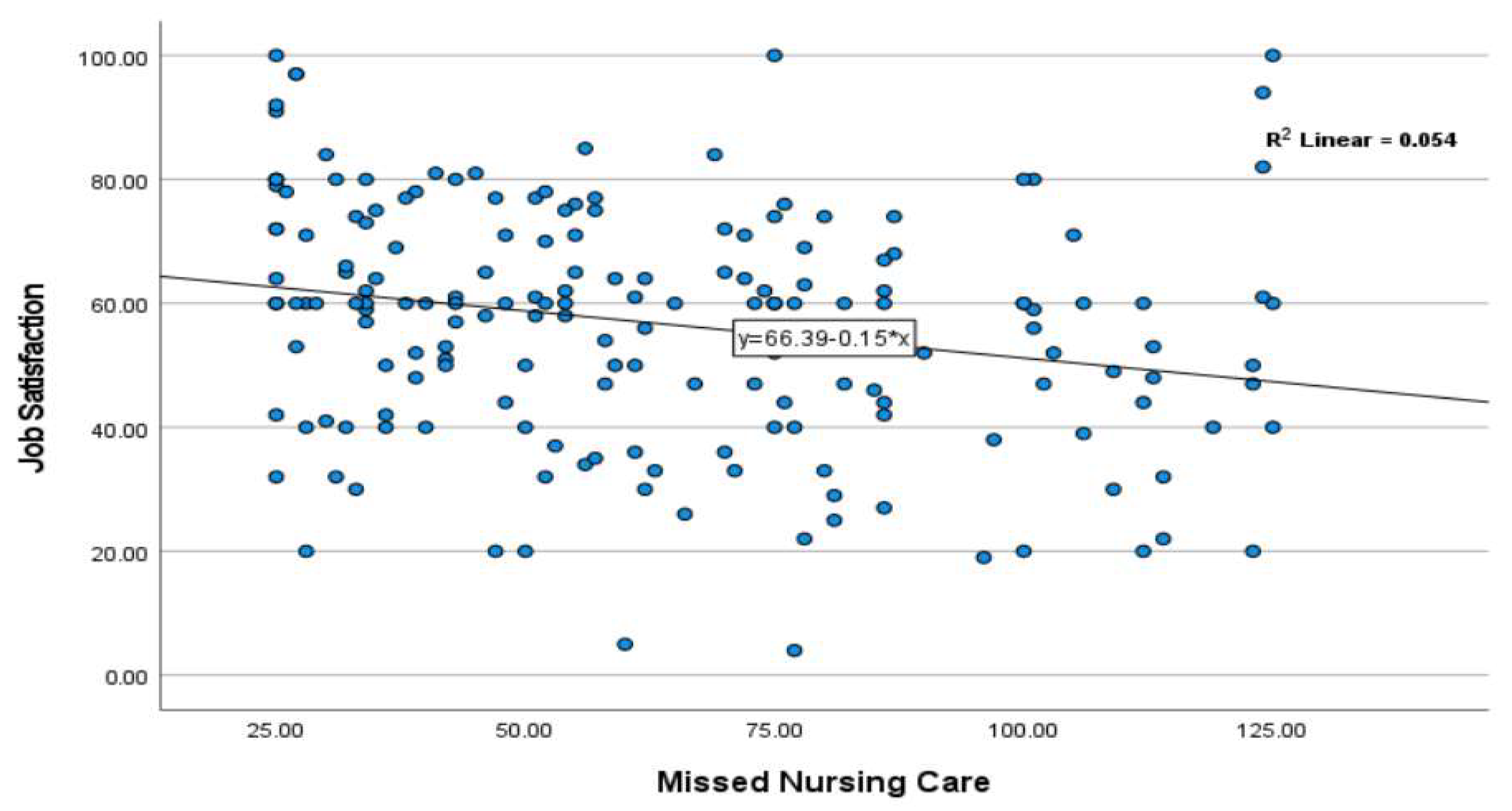

3.5. Correlation Between Missed Nursing Care and Job Satisfaction

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Perspective for Clinical Practice

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Public Involvement Statement

Guidelines and Standards Statement

Use of Artificial Intelligence

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MNC | Missed Nursing Care |

| ER | Emergency Room |

| STROBE | Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology |

| MSQ | Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire |

| ICU | Intensive Care Unit |

| SPSS | Statistical Package for the Social Sciences |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| IQR | Interquartile Range |

References

- Edfeldt, K.; Nyholm, L.; Jangland, E.; Gunnarsson, A.-K.; Fröjd, C.; Hauffman, A. Missed Nursing Care in Surgical Care—A Hazard to Patient Safety: A Quantitative Study within the inCHARGE Programme. BMC Nurs. 2024, 23, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalisch, B.J.; Landstrom, G.; Williams, R.A. Missed Nursing Care: Errors of Omission. Nurs. Outlook 2009, 57, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, E.M.; Aiken, L.H.; McHugh, M.D. Registered Nurse Burnout, Job Dissatisfaction, and Missed Care in Nursing Homes. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2019, 67, 2065–2071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Algin, A.; Yesilbas, H.; Kantek, F. The Relationship Between Missed Nursing Care and Nurse Job Satisfaction: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. West. J. Nurs. Res. 2024, 46, 980–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Labrague, L.J.; Cayaban, A.R. Association Between Patient Safety Culture and Missed Nursing Care in Healthcare Settings: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Adv. Nurs. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Muharraq, E.H.; Alallah, S.M.; Alkhayrat, S.A.; Jahlan, A.G. An Overview of Missed Nursing Care and Its Predictors in Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Nurs. Res. Pract. 2022, 2022, 4971890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alsalem, N.; Rashid, F.A.; Aljarudi, S.; Al Bazroun, M.I.; Almatrouk, R.M.; Alharbi, F.M.; Al Mansour, L.; Abuzaid, N.B. Exploring Missed Nursing Care in the NICU: Perspectives of NICU Nurses in Saudi Arabia’s Eastern Health Cluster. Pediatr. Rep. 2023, 15, 571–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drennan, J.; Murphy, A.; McCarthy, V.J.C.; Ball, J.; Duffield, C.; Crouch, R.; Kelly, G.; Loughnane, C.; Murphy, A.; Hegarty, J.; et al. The Association between Nurse Staffing and Quality of Care in Emergency Departments: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2024, 153, 104706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nantsupawat, A.; Poghosyan, L.; Wichaikhum, O.-A.; Kunaviktikul, W.; Fang, Y.; Kueakomoldej, S.; Thienthong, H.; Turale, S. Nurse Staffing, Missed Care, Quality of Care and Adverse Events: A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Nurs. Manag. 2022, 30, 447–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, P.; Recio-Saucedo, A.; Dall’Ora, C.; Briggs, J.; Maruotti, A.; Meredith, P.; Smith, G.B.; Ball, J.; Missed Care Study Group. The Association between Nurse Staffing and Omissions in Nursing Care: A Systematic Review. J. Adv. Nurs. 2018, 74, 1474–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hessels, A.; Paliwal, M.; Weaver, S.H.; Siddiqui, D.; Wurmser, T.A. Impact of Patient Safety Culture on Missed Nursing Care and Adverse Patient Events. J. Nurs. Care Qual. 2019, 34, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshammari, B.; Pangket, P.; Alrasheeday, A.; Baghdadi, N.; Alkubati, S.A.; Cabansag, D.; Gugoy, N.; Alshammari, S.M.; Alanazi, A.; Alanezi, M.D.; et al. The Mediating Role of Burnout in the Relationship Between Emotional Intelligence and Work Engagement Among Hospital Nurses: A Structural Equation Modeling Approach. Nurs. Rep. 2025, 15, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Haroon, H.I.; Al-Qahtani, M.F. The Demographic Predictors of Job Satisfaction among the Nurses of a Major Public Hospital in KSA. J. Taibah Univ. Med. Sci. 2020, 15, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, D.J.; Dawis, R.V.; England, G.W. Manual for the Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire. Minn. Stud. Vocat. Rehabil. 1967, 22, 120. [Google Scholar]

- Blackman, I.; Henderson, J.; Willis, E.; Hamilton, P.; Toffoli, L.; Verrall, C.; Abery, E.; Harvey, C. Factors Influencing Why Nursing Care Is Missed. J. Clin. Nurs. 2015, 24, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsadaan, N.; Jones, L.K.; Kimpton, A.; DaCosta, C. Challenges Facing the Nursing Profession in Saudi Arabia: An Integrative Review. Nurs. Rep. 2021, 11, 395–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alluhidan, M.; Tashkandi, N.; Alblowi, F.; Omer, T.; Alghaith, T.; Alghodaier, H.; Alazemi, N.; Tulenko, K.; Herbst, C.H.; Hamza, M.M.; et al. Challenges and Policy Opportunities in Nursing in Saudi Arabia. Hum. Resour. Health 2020, 18, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daheshi, N.; Alkubati, S.A.; Villagracia, H.; Pasay-an, E.; Alharbi, G.; Alshammari, F.; Madkhali, N.; Alshammari, B. Nurses’ Perception Regarding the Quality of Communication between Nurses and Physicians in Emergency Departments in Saudi Arabia: A Cross Sectional Study. Healthcare 2023, 11, 645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alshammari, B.; Alanazi, N.F.; Kreedi, F.; Alshammari, F.; Alkubati, S.A.; Alrasheeday, A.; Madkhali, N.; Alshara, A.; Bakthavatchaalam, V.; Al-Masaeed, M.; et al. Exposure to Secondary Traumatic Stress and Its Related Factors among Emergency Nurses in Saudi Arabia: A Mixed Method Study. BMC Nurs. 2024, 23, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almalki, M.; Fitzgerald, G.; Clark, M. Health Care System in Saudi Arabia: An Overview. East. Mediterr. Health J. 2011, 17, 784–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: Guidelines for Reporting Observational Studies. BMJ 2007, 335, 806–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalisch, B.J.; Williams, R.A. Development and Psychometric Testing of a Tool to Measure Missed Nursing Care. J. Nurs. Adm. 2009, 39, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palese, A.; Navone, E.; Danielis, M.; Vryonides, S.; Sermeus, W.; Papastavrou, E. Measurement Tools Used to Assess Unfinished Nursing Care: A Systematic Review of Psychometric Properties. J. Adv. Nurs. 2021, 77, 565–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dziedzic, B.; Jagiełło, M.; Kobos, E.; Sienkiewicz, Z.; Czyżewski, Ł. Job Satisfaction among Nurses Working in Hospitals during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Med. Pracy Work. Health Saf. 2023, 74, 271–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alotaibi, A. Work Environment and Its Relationship with Job Satisfaction Among Nurses in Riyadh Region, Saudi Arabia. Doctoral Dissertation, Majmaah University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Mainz, H.; Tei, R.; Andersen, K.V.; Lisby, M.; Gregersen, M. Prevalence of Missed Nursing Care and Its Association with Work Experience: A Cross-Sectional Survey. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. Adv. 2024, 6, 100196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Ahmadi, H.A. Job Satisfaction of Nurses in Ministry of Health Hospitals in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med. J. 2002, 23, 645–650. [Google Scholar]

- Almansour, H.; Aldossary, A.; Holmes, S.; Alderaan, T. Migration of Nurses and Doctors: Pull Factors to Work in Saudi Arabia. Hum. Resour. Health 2023, 21, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chegini, Z.; Jafari-Koshki, T.; Kheiri, M.; Behforoz, A.; Aliyari, S.; Mitra, U.; Islam, S.M.S. Missed Nursing Care and Related Factors in Iranian Hospitals: A Cross-sectional Survey. J. Nurs. Manag. 2020, 28, 2205–2215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.; Lee, J.; You, S.J.; Song, K.J.; Hong, K.J. Nurse Staffing, Nurses Prioritization, Missed Care, Quality of Nursing Care, and Nurse Outcomes. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2020, 26, e12803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khajoei, R.; Balvardi, M.; Eghbali, T.; Yousefi, M.S.; Forouzi, M.A. Missed Nursing Care and Related Factors: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Nurs. 2025, 24, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, E.; Kalisch, B.J. Identification and Comparison of Missed Nursing Care in the United States of America and South Korea. J. Clin. Nurs. 2021, 30, 1596–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.H.; Hanchett, M.; Ma, C. Practice Environment Characteristics Associated With Missed Nursing Care. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2018, 50, 722–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UC Davis PSNet Editorial Team. Missed Nursing Care; Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, US Department of Health and Human Services: Rockville, MD, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Hammad, M.; Guirguis, W.; Mosallam, R. Missed Nursing Care, Non-Nursing Tasks, Staffing Adequacy, and Job Satisfaction among Nurses in a Teaching Hospital in Egypt. J. Egypt. Public Health Assoc. 2021, 96, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| 98 (26.8) |

| 268 (73.2) |

| Gender | |

| 46 (12.6) |

| 320 (87.4) |

| Marital Status | |

| 130 (35.5) |

| 206 (56.3) |

| 30 (8.2) |

| Nationality | |

| 354 (96.7) |

| 12 (3.3) |

| Educational Level | |

| 96 (26.2) |

| 218 (59.6) |

| 52 (14.2) |

| Years of Experience | |

| 46 (53.5) |

| 40 (46.5) |

| Department | |

| 76 (20.8) |

| 44 (12.0) |

| 40 (10.9) |

| 60 (16.4) |

| 12 (3.3) |

| 12 (3.3) |

| 122 (33.4) |

| Shift Type | |

| 204 (55.7) |

| 22 (6.0) |

| 140 (38.3) |

| Nurse-to-Patient Ratio | |

| 112 (30.6) |

| 92 (25.1) |

| 42 (11.5) |

| 120 (32.8) |

| n | (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Job Satisfaction | Low (20–47) | 92 | (25.1) |

| Moderate (48–76) | 188 | (51.4) | |

| High (77–100) | 86 | (23.5) | |

| Variable | N | Missed Nursing Care | Job Satisfaction | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Rank | p-Value | Mean Rank | p-Value | |||

| Age | ≤30 Years | 98 | 90.59 | 0.828 | 91.52 | 0.941 |

| >30 Years | 268 | 92.51 | 92.18 | |||

| Gender | Male | 46 | 92.39 | 0.970 | 91.43 | 0.956 |

| Female | 320 | 91.94 | 92.08 | |||

| Nationality | Saudi | 354 | 92.45 | 0.531 | 92.01 | 0.984 |

| Non-Saudi | 12 | 78.67 | 91.58 | |||

| Experience | ≤6 Years | 46 | 21.41 | 0.742 | 23.85 | 0.299 |

| >6 Years | 40 | 22.68 | 19.88 | |||

| Marital Status | Single | 130 | 90.14 | 0.594 | 93.29 | 0.902 |

| Married | 206 | 94.81 | 90.58 | |||

| Divorced/Widowed | 30 | 80.80 | 96.17 | |||

| Educational level | Diploma | 96 | 82.73 | 0.273 | 99.36 | 0.460 |

| Bachelor | 218 | 93.57 | 88.18 | |||

| Postgraduate | 52 | 102.54 | 94.40 | |||

| Department | ER | 76 | 90.76 | 0.747 | 87.47 | 0.099 |

| ICU | 44 | 100.07 | 88.80 | |||

| Medical–Surgical Unit | 40 | 94.33 | 73.88 | |||

| Pediatric | 60 | 87.57 | 103.03 | |||

| Obstetrics/Gynecology | 12 | 130.58 | 66.67 | |||

| Psychiatric Unit | 12 | 70.42 | 78.83 | |||

| Others | 122 | 89.93 | 110.46 | |||

| Shift Type | Day shift | 204 | 95.90 | 0.226 | 91.86 | 0.992 |

| Night shift | 22 | 106.55 | 90.36 | |||

| Rotating shifts | 140 | 84.03 | 92.46 | |||

| Nurse-to-Patient Ratio | 1–3 | 112 | 98.50 | 0.576 | 91.87 | 0.887 |

| 4–6 | 92 | 94.38 | 96.10 | |||

| 7–9 | 42 | 83.76 | 85.10 | |||

| 10 or more | 120 | 86.99 | 91.40 | |||

| Variable | Correlation Coefficient (r) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Missed Nursing Care vs. Job Satisfaction | −0.267 ** | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alshammari, B.; Alshammari, M.M.; Baghdadi, N.A. The Association Between Missed Nursing Care and Job Satisfaction Among Nurses in Saudi Arabian Hospitals: A Cross-Sectional Study. Nurs. Rep. 2025, 15, 296. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15080296

Alshammari B, Alshammari MM, Baghdadi NA. The Association Between Missed Nursing Care and Job Satisfaction Among Nurses in Saudi Arabian Hospitals: A Cross-Sectional Study. Nursing Reports. 2025; 15(8):296. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15080296

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlshammari, Bushra, Munirah Matar Alshammari, and Nadiah A. Baghdadi. 2025. "The Association Between Missed Nursing Care and Job Satisfaction Among Nurses in Saudi Arabian Hospitals: A Cross-Sectional Study" Nursing Reports 15, no. 8: 296. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15080296

APA StyleAlshammari, B., Alshammari, M. M., & Baghdadi, N. A. (2025). The Association Between Missed Nursing Care and Job Satisfaction Among Nurses in Saudi Arabian Hospitals: A Cross-Sectional Study. Nursing Reports, 15(8), 296. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15080296