Mapping Care Practices and Service Delivery Models for Refugee and Displaced Families in Private Hosting Arrangements: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.2. Search Strategy

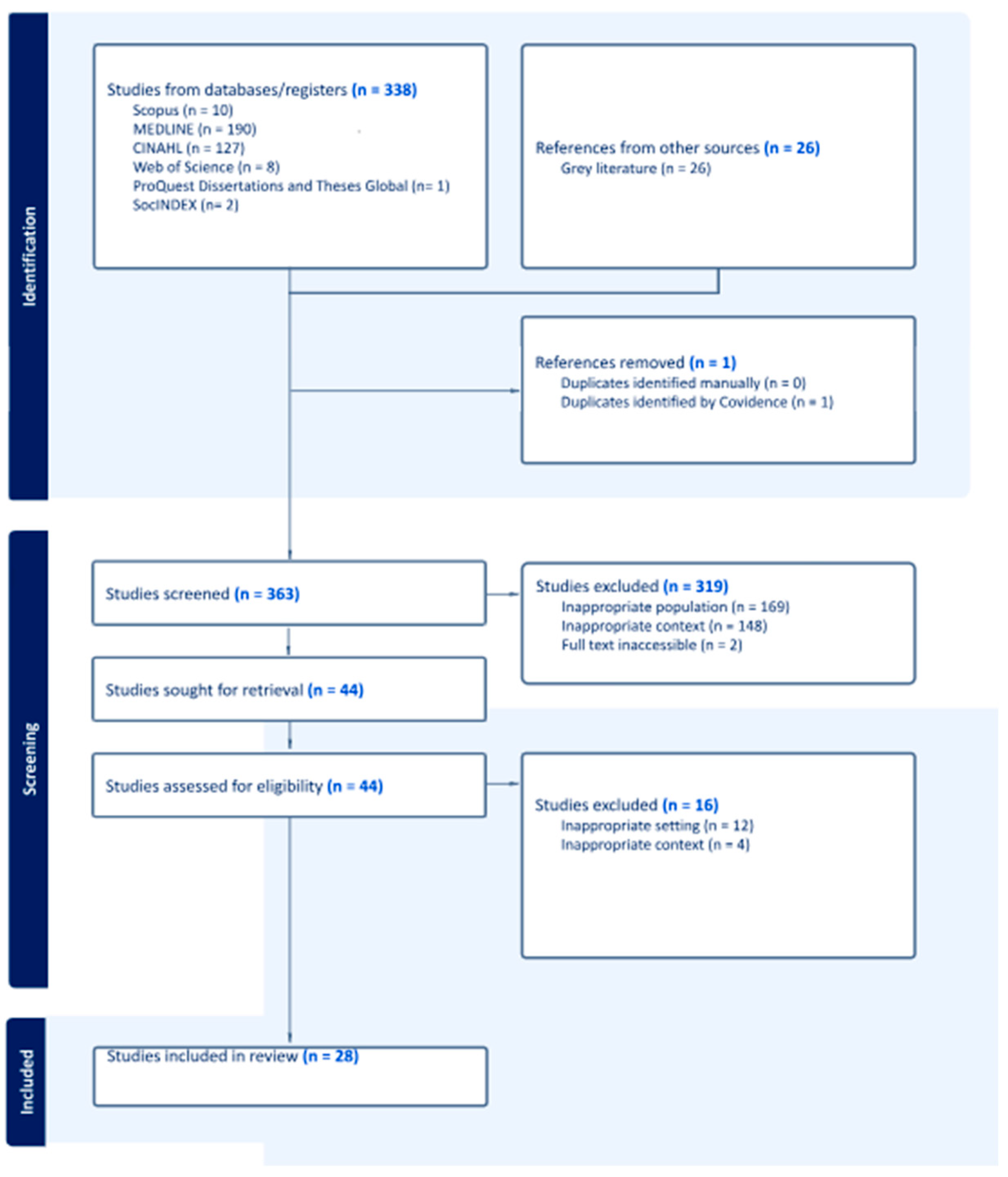

2.3. Study Selection and Extraction

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Description of Studies

3.2. Relational Care and Trust-Building as Core to Effective Hosting (Interpersonal Dimension)

3.3. Program Structure, Support Systems, and Policy Integration (Structural Dimension)

3.4. Holistic Integration Pathways (Integration Dimension)

3.5. Embedding Equity, Protection, and Accountability in Hosting Design (Protection Dimension)

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications

4.2. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Public Involvement Statement

Guidelines and Standards Statement

Use of Artificial Intelligence

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| JBI | Joanna Briggs Institute |

| (PRISMA-ScR) | Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews |

| PCC | Population, Concept, and Context |

References

- Al-Hamad, A.; Yasin, Y.M.; Metersky, K.; Guruge, S.; Hingorani, M.; Gare, C. Picturing the ambiguity of homestay: A photovoice exploration of Ukrainian refugee women’s experiences with their Canadian hosts in Toronto. Cogent Arts Humanit. 2025, 12, 2472536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Hosting Arrangements; United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Hamad, A.; Yasin, Y.M.; Metersky, K.; Guruge, S.; Gare, C.; Hingorani, M. Successful Refugee Cohabitation with Host Families: A Concept Analysis and Model Development. J. Holist. Nurs. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Government of Canada. Private Sponsorship of Refugees Program; Refugee Sponsorship Training Program: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Phillimore, J.; Soto, M.R. Community Sponsorship in the UK: From Application to Integration; University of Birmingham: Birmingham, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Refugees at Home. Making Space for What Matters. Available online: https://refugeesathome.org/?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Burrell, K. Domesticating Responsibility: Refugee Hosting and the Homes for Ukraine Scheme. Antipode 2024, 56, 1191–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Haren, I. Canada’s Private Sponsorship Model Represents a Complementary Pathway for Refugee Resettlement; Migration Policy Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Hamad, A.; Yasin, Y.M.; Metersky, K.; Guruge, S.; Jung, G.; Mahsud, K. Homestay Hosting Dynamics and Refugee Well-Being: Scoping Review. Interact. J. Med. Res. 2024, 13, e58613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrawadieh, Z.; Altinay, L.; Urbančíková, N.; Hudec, O. Refugees at home: The role of hospitableness in fostering pro-social attitudes and behaviours towards refugees. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2023, 36, 3052–3071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, A. Community Sponsorship in the U.S: Motivations and Outcomes of Sponsorship. Available online: https://communitysponsorshiphub.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/Motivations-and-Outcomes-of-Sponsorship_June-2025-CSH.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Darling, J. Hosting the Displaced: From Sanctuary Cities to Hospitable Homes. In The Handbook of Displacement; Adey, P., Bowstead, J.C., Brickell, K., Desai, V., Dolton, M., Pinkerton, A., Siddiqi, A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 785–798. [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch, A.L.; Hoang, K.; Vogl, A. Australia’s Private Refugee Sponsorship Program: Creating Complementary Pathways or Privatising Humanitarianism? Refuge 2019, 35, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herpell, M.; Marbach, M.; Harder, N.; Orlova, A.; Hangartner, D.; Hainmueller, J. The Impact of Private Hosting on the Integration of Ukrainian Refugees; Immigration Policy Lab: Stanford, CA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dauphin, A.; Veronis, L. The role of private sponsorship on refugee resettlement outcomes: A mixed methods study of Syrians in a mid-sized city with a linguistic minority. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2024, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortinovis, R.; Fallone, A. Identifying Criteria for Complementary Pathways to Provide Sustainable Solutions for Refugees: Two Canadian Case Studies. In Global Asylum Governance and the European Union’s Role: Rights and Responsibility in the Implementation of the United Nations Global Compact on Refugees; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 113–132. [Google Scholar]

- Korteweg, A.; Shauna, L.; Macklin, A. Humanitarian bargains: Private refugee sponsorship and the limits of humanitarian reason. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2023, 49, 3958–3975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, J.; Caroline, L.; Al Kalmashi, R. Who is the Host? Interrogating Hosting from Refugee-Background Women’s Perspectives. J. Intercult. Stud. 2022, 43, 621–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hamad, A.; Yasin, Y.M. Intersectional insights into hosting frameworks for refugee women in Canada. Int. J. Soc. Sci. Res. Rev. 2024, 7, 215–226. [Google Scholar]

- Kulovic, D. The Refugee–Burden of the Decade, or an Economic Opportunity?: A Qualitative Study on the Role of the Private Sector in Creating Sustainable Solutions for Refugees in Developing Countries Through Local Integration. Master′s Thesis, NHH Norwegian School of Economics, Bergen, Norway, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hyndman, J.; Reynolds, J.; Yousuf, B.; Purkey, A.; Demoz, D.; Sherrell, K. Sustaining the Private Sponsorship of Resettled Refugees in Canada. Front. Hum. Dyn. 2021, 3, 2673–2726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labman, S. Private Sponsorship Complementary or Conflicting Interests? Refug. Canada’s J. Refug. 2016, 32, 67–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berneri, C. Private Sponsorship of Refugees in Europe, 1st ed.; Bloomsbury Publishing: London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, M.D.; Godfrey, C.M.; McInerney, P.; Soares, C.B.; Khalil, H.; Parker, D. The Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewers’ Manual 2015: Methodology for JBI Scoping Reviews; JBI: Adelaide, Australia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pollock, D.; Alexander, L.; Munn, Z.; Peters, M.D.J.; Khalil, H.; Godfrey, C.M.; McInerney, P.; Synnot, A.; Tricco, A.C. Moving from consultation to co-creation with knowledge users in scoping reviews: Guidance from the JBI Scoping Review Methodology Group. JBI Evid. Synth. 2022, 20, 969–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGowan, J.; Sampson, M.; Salzwedel, D.M.; Cogo, E.; Foerster, V.; Lefebvre, C. PRESS peer review of electronic search strategies: 2015 guideline statement. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2016, 75, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giustini, D. Retrieving Grey Literature, Information, and Data in the Digital Age. In The Handbook of Research Synthesis and Meta-Analysis; Harris Cooper, L.V.H., Jeffrey, C.V., Eds.; Russell Sage Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 101–126. [Google Scholar]

- Piper, C. System for the unified management, assessment, and review of information (SUMARI). J. Med. Libr. Assoc. JMLA 2019, 107, 634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vears, D.F.; Gillam, L. Inductive content analysis: A guide for beginning qualitative researchers. Focus Health Prof. Educ. Multi-Prof. J. 2022, 23, 111–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abuhaloob, L.; Carson, S.; Richards, D.; Freeman, R. Community-based nutrition intervention to promote oral health and restore healthy body weight in refugee children: A scoping review. Community Dent. Health 2018, 35, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canter, A.; Lyons, K.; Fidler, M. ‘It′s Like Airbnb for Refugees’: UK Hosts and Their Guests—In Pictures. The Guardian Picture Essay, 8 May 2017; p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Sirriyeh, A. Hosting strangers: Hospitality and family practices in fostering unaccompanied refugee young people. Child Fam. Soc. Work 2013, 18, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stock, I. Buddy schemes between refugees and volunteers in Germany: Transformative potential in an unequal relationship. Soc. Incl. 2019, 7, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, Z. “If I fall down, he will pick me up”: Refugee hosts and everyday care in protracted displacement. Front. Hum. Dyn. 2024, 6, 1282535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monforte, P.; Maestri, G.; d’Halluin, E. ‘It’s like having one more family member’: Private hospitality, affective responsibility and intimate boundaries within refugee hosting networks. J. Sociol. 2021, 57, 674–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Immigration Refugees and Citizenship Canada. Canada Provides More Support to Refugees and Those Who Host Them; Immigration Refugees and Citizenship Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Keung, N. Could This Project Help Address Our Housing Crisis and Put a Roof Over Refugees’ Heads? FCJ Refugee Centre: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Operation Ukrainian Safe Haven. Housing. Available online: https://ukrainesafehaven.ca/get-involved/housing/ (accessed on 16 March 2025).

- Refugee Housing Canada Program. Help a Refugee by Opening Your Home. Available online: https://refugeehousing.ca/ (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- UNHCR. Refugee Resettlement to Canada. Available online: https://www.unhcr.ca/in-canada/unhcr-role-resettlement/refugee-resettlement-canada/ (accessed on 22 January 2025).

- Al-Hamad, A.; Metersky, K. Homestays Can Help Refugee Women Get to Grips with Life in a New Country; The Conversation: Carlton, Australia, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Peisakhin, L.; Stoop, N.; van der Windt, P. Here’s What Motivates People to Host Refugees; KU Leuven: Leuven, Belgium, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Abu-Ras, W.; Almoayad, F.; Bakry, H.M.; Alammari, D.; Kelly, P.J.; Aboul-Enein, B.H. Interventions to promote mental health in the Occupied Palestinian Territories and Palestinian refugees: A scoping review. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2024, 70, 1037–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD). Housing Support for Ukrainian Refugees in Receiving Countries. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/publications/reports/2022/07/housing-support-for-ukrainian-refugees-in-receiving-countries_ebec3000/9c2b4404-en.pdf (accessed on 19 January 2025).

- International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC). World Refugee Day: Europe’s Experience with ‘Private Hosting’ of Ukrainian Refugees Offers a New Model for Supporting People Fleeing Conflict and Violence. Available online: https://www.ifrc.org/article/world-refugee-day-europes-experience-private-hosting-ukrainian-refugees-offers-new-model (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- Caron, M. Hosting as shelter during displacement: Considerations for research and practice. J. Int. Humanit. Action 2019, 4, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hamad, A.; Yasin, Y.M.; Metersky, K.; Guruge, S.; Mahsud, K. Homestay Hosting Dynamics and Refugee Well-Being: Protocol for a Scoping Review. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2024, 13, e56242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, Z. Why Host Refugees? Refugee Hosts: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Refugees Welcome International. Do You Have a Spare Room in Your Flat or Home? Available online: https://www.refugees-welcome.net/offer-a-room/ (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Room for Refugees Network. Host a Refugee Family or Individual in Your Home; Positive Action in Housing: Glasgow, UK, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- The No Accomodation Network. Host a Refugee in Your Home. Available online: https://naccom.org.uk/get-involved/happytohost-initial-enquiries/ (accessed on 23 January 2025).

| Criteria | Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Literature Type | Peer-reviewed and gray literature (e.g., UNHCR, NGOs, government reports), including commentaries, editorials, opinion pieces, websites, newspapers, and letters to the editor. | Duplicate sources or retracted publications and literature that are not publicly accessible. |

| Study Type | All study types (qualitative, quantitative, mixed-methods studies were included only if findings from private hosting could be disaggregated and various forms of relevant reviews). | Duplicate studies of the same study without new or additional analysis or incomplete conference abstracts. |

| Language | English. | Non-English publications |

| Publication Date | January 2000–April 2025. | Published before January 2000 or after April 2025. |

| Population | Refugee and displaced families (including asylum seekers, stateless individuals, and those forcibly displaced due to conflict or disaster). | Populations not identified as refugee/displaced or lacking clarity on displacement status. |

| Context | Private hosting arrangements (i.e., settings where refugee or displaced families are accommodated within private homes). | Institutional settings (e.g., camps, shelters, group homes). |

| Concept | Care practices and service delivery models considered “care practices,” | Care practices and service delivery models that do not focus on refugee or displaced populations in the context of private hosting. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Al-Hamad, A.; Yasin, Y.M.; Yasin, L.; Zhang, A. Mapping Care Practices and Service Delivery Models for Refugee and Displaced Families in Private Hosting Arrangements: A Scoping Review. Nurs. Rep. 2025, 15, 293. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15080293

Al-Hamad A, Yasin YM, Yasin L, Zhang A. Mapping Care Practices and Service Delivery Models for Refugee and Displaced Families in Private Hosting Arrangements: A Scoping Review. Nursing Reports. 2025; 15(8):293. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15080293

Chicago/Turabian StyleAl-Hamad, Areej, Yasin M. Yasin, Lujain Yasin, and Andy Zhang. 2025. "Mapping Care Practices and Service Delivery Models for Refugee and Displaced Families in Private Hosting Arrangements: A Scoping Review" Nursing Reports 15, no. 8: 293. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15080293

APA StyleAl-Hamad, A., Yasin, Y. M., Yasin, L., & Zhang, A. (2025). Mapping Care Practices and Service Delivery Models for Refugee and Displaced Families in Private Hosting Arrangements: A Scoping Review. Nursing Reports, 15(8), 293. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15080293