Nursing Care to Reduce Suicide Risk in Cancer Patients: A Narrative Review of the Literature

Abstract

1. Introduction

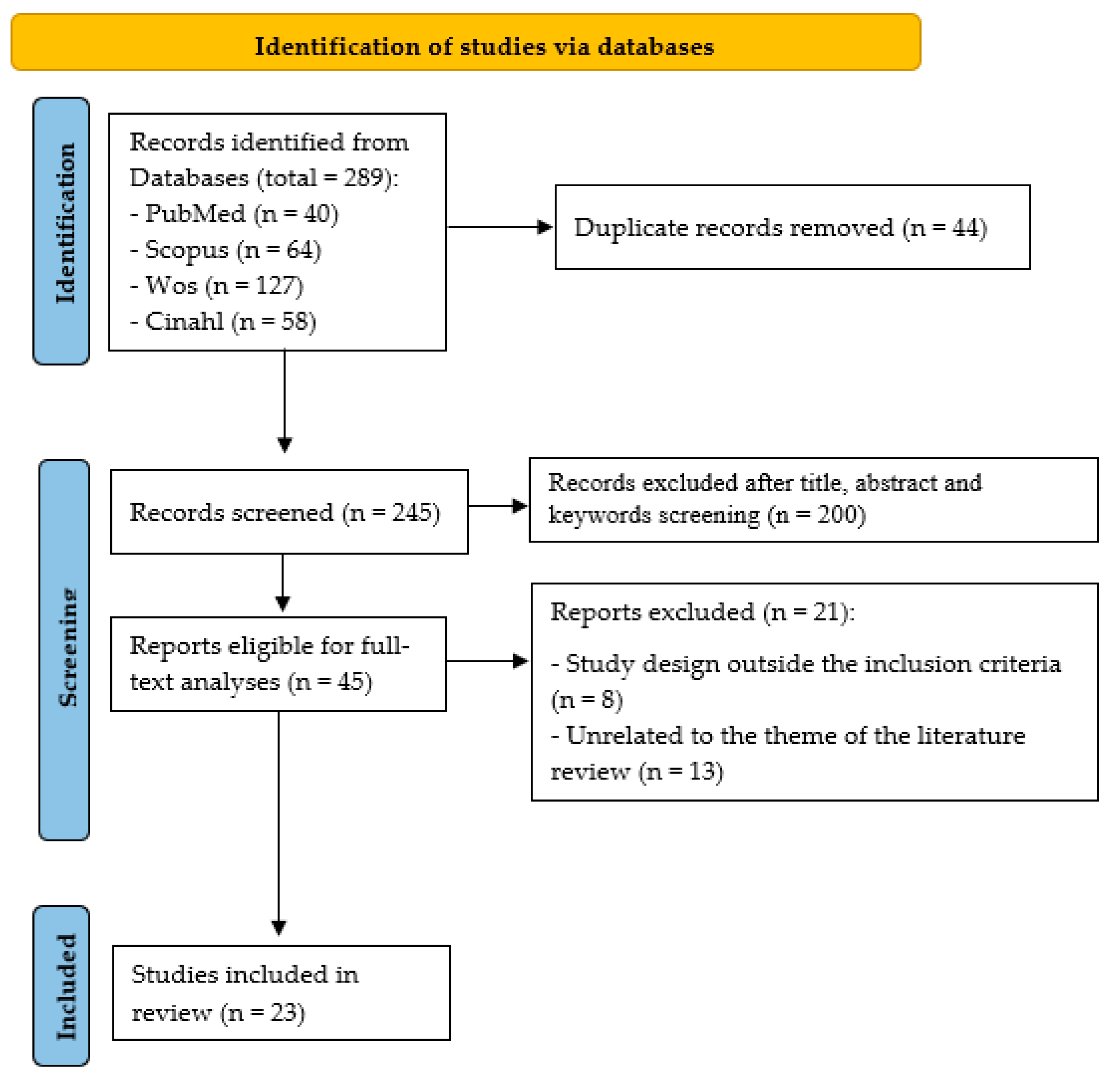

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Search Strategy

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Selection of Articles

2.4. Data Extraction

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Description of the Studies and Characterictics of the Sample

3.2. Study Outcome

3.2.1. Demographic, Socio-Economic, Psycho-Emotional, and Physical Factors Associated with Suicide Risk in Cancer Patients

3.2.2. Nursing Care to Reduce the Risk of Suicide in Oncology Patients

- (1)

- Systematic suicide risk assessment: Seventeen studies emphasised the importance of applying validated tools to assess suicide risk. Instruments such as the Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS) and the Plutchik Suicide Risk Scale are recommended for baseline assessment and periodic reassessment—ideally every three months or following major clinical or psycho-social changes [31,33,34,35,36,37,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,52]. These tools should be complemented by clinical interviews and regular review of patient records to ensure early identification of risk [35,48,52].

- (2)

- Professional training and communication skills development: Eight studies underlined the need for continuous professional development focused on suicide risk recognition, empathic communication, and ethical support practices [35,36,39,40,43,44,45,46]. Proposed strategies include annual workshops, case simulations, and structured communication protocols to improve nurses’ capacity to detect warning signs such as hopelessness or existential distress [35,39,43,45].

- (3)

- Therapeutic and supportive nursing interventions: Several studies reported the effectiveness of specific nursing interventions to alleviate emotional and physical suffering. These include progressive muscle relaxation, therapeutic walking, aromatherapy, behavioural activation therapy, and problem-solving approaches. Such techniques are seen to reduce anxiety, depressive symptoms, and physical discomfort while enhancing quality of life [40,43,45].

- (4)

- Integration into routine clinical practice and interdisciplinary coordination: Some authors advocated for embedding suicide risk assessment into standard nursing documentation and shift reports to promote consistency in detection and follow-up [35,41,46]. Coordination with mental health professionals and social workers was also considered essential to ensure timely and effective response to high-risk cases [45,47].

- (5)

- Family and caregiver support: Eight studies extended suicide prevention strategies to include family members and caregivers, especially in cases involving advanced cancer or young survivors. Interventions included emotional support for caregivers, identification of their own suicide risk or psychological distress, and provision of coping tools and referrals to specialised care when necessary [32,38,47,48,49,50,51,52].

| Authors | Study Design/Methods | Study Period/ Sample/Country | Suicide Risk Factors | Nursing Care |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schwinn et al. [50] | Mixed-methods study. Methods: On the qualitative side, semi-structured interviews were conducted focusing on work experience in oncology, experiences with suicidal behaviour, and suicide risk assessment. The average interview duration was 39.47 ± 8.35 min. Content analysis of the interview transcripts was carried out using MAXQDA R22.7 V5 software. For the quantitative data collection, a questionnaire was administered. Data analysis was performed using R Statistics V.4.3.1. | Period: Not reported. Sample: 20 healthcare professionals from an oncology unit (female: 70%; mean age: 41.45 ± 9.7 years). Country: Germany. | Demographic: Male sex. Socio-economic: Not reported. Psycho-emotional: Not reported. Physical: Worsening of physical symptoms. | The authors highlight the need for adequate training, clear guidelines, validated tools, and referral pathways to support the identification and management of suicidal behaviour. They recommend systematic risk assessment (e.g., C-SSRS) and fostering a trusting relationship with the patient and their family. |

| Espuig et al. [31] | Quantitative study. Methods: Questionnaires used: SF-36, B-IPQ, HADS and Plutchik Suicide Risk Scale. Descriptive analysis of socio-demographic and clinical variables was conducted using SPSS 28.0. Pearson correlations were used to examine associations, and linear regression analysis was performed to identify predictors of suicide risk. | Period: 2019–2024 Sample: 71 patients (female: 29.94%; mean age: 65.18 ± 12.02 years) Country: Spain | Demographic: Single, widowed, and childless. Socio-economic: Lack of social support, limited access to healthcare, and economic instability. Psycho-emotional: Emotional distress and perceived threat. Physical: Pain. | It is essential to address both physical and emotional needs to reduce anxiety and stress. Suicide risk should be assessed systematically. Establishing a trusting relationship and acting as a link between the patient, family, and professionals is key. Effective communication—clear, supportive, and accessible—helps decision-making, coping, and self-care. |

| Öztürk & Hiçdurmaz [23] | Qualitative study. Methods: Data were collected both in person and online, and subsequently via email from individuals who had previously participated. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS and SPSS AMOS v.20.0. Continuous variables were assessed using the median and interquartile range, while categorical variables were presented as frequencies and percentages. | Period: 2021–2022 Sample: 252 oncology nurses (female: 91%; mean age: 29 years) Country: Türkiye | Demographic: Low educational level. Socio-economic: Poverty and unemployment. Psycho-emotional: Depression, anxiety, emotional distress, and presence of psychiatric illness. Physical: Associated physical discomfort. | It is important to identify suitable psycho-social resources for each individual. This requires nursing staff to be trained in empathic communication. The Perceived Effectiveness in Suicide Risk Management Scale is recommended to guide training and evaluate protocols. |

| Zhang et al. [32] | Quantitative study. Methods: Use of the SRI-25 questionnaire. Descriptive techniques, univariate tests, and Pearson correlations were applied for analysis. Additionally, a serial multiple mediation model (PROCESS Model 6) was used to assess mediation effects. | Period: January to March 2022 Sample: 287 cancer patients (female: 58.2%; mean age: not reported) Country: China | Demographic: Not reported. Socio-economic: Lack of social support; unemployment. Psycho-emotional: Lack of coping tools. Physical: Lack of physical activity. | The authors recommend providing continuous emotional support, reinforcing self-care and symptom management strategies, and addressing feelings of burden or guilt. Involving family caregivers is also key to strengthening the patient’s support network and sense of purpose. |

| Zheng et al. [33] | Quantitative study. Methods: The following scales were used: SSQ, MINI Suicide Subscale, PHQ-9, GAD-7 and DT Statistical data analysis was conducted using SPSS v.27.0, PASS v.2021, and Microsoft Excel v.2016. | Period: March 2018–August 2023 Sample: 9703 cancer patients (female: 73.47%; mean age: 49.69 ± 11.59 years) Country: China | Demographic: Not reported. Socio-economic: Changes in social roles. Psycho-emotional: Depression and anxiety. Physical: Pain, fatigue, and weakness. | The authors highlight the Single Suicide Question (SSQ) as a useful initial tool for detecting suicide risk in cancer patients. However, they stress the need to develop simple, concise oncology-specific methods to improve response quality. Nurses should be trained in using these assessment tools. |

| Hu et al. [34] | Quantitative study. Methods: Data were obtained from the North American Cancer Incidence Survival Registry (NA-CISR) and the National Centre for Health Statistics. Two analyses were conducted: 1. Standardised mortality ratios; 2. Risk ratio estimation using regression analysis. | Period: 2000–2016 Sample: 16,954,604 cancer patients (female: 48.5%; mean age: not reported) Country: United States | Demographic: Male sex, non-Hispanic white ethnicity, advanced age, rural residence. Socio-economic: Lack of healthcare coverage under Medicare. Psycho-emotional: Not reported. Physical: High symptom burden. | The authors highlight the importance of suicide risk screening and personalised psycho-oncological interventions, alongside developing clear clinical guidelines. These measures promote early intervention, improve access to support, and strengthen resilience. |

| Katayama et al. [35] | Quantitative study. Methods: Data were collected based on information identified in Medicare. Clinical, demographic, and mental health variables were gathered, along with social vulnerability index and access to mental health services. Analysis included descriptive statistics, chi-square tests, multivariable logistic regression, and variable interaction analysis. | Period: 2004–2016 Sample: 382,266 cancer patients (female: 47.6%; mean age: 72.0 years) Country: United States | Demographic: Male, single, white ethnicity. Socio-economic: Social isolation, limited access to mental health care. Psycho-emotional: Depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder. Physical: Treatment-related physical issues and disability. | Systematic detection and screening using self-report questionnaires such as PHQ-9, BHS, and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, complemented by regular review of medical records to identify risk factors. Enhancing training and education on suicide risk factors in cancer patients is essential, along with ensuring timely referrals to mental health professionals. |

| Öztürk & Hiçdurmaz [43] | Qualitative study. Methods: Data were collected through individual, face-to-face semi-structured interviews. A content analysis was conducted. The COREQ guidelines were followed for report preparation. The average duration of the interviews was 39.3 ± 7.1 min. | Period: July–October 2019. Sample: 33 oncology nurses (female: 90%; mean age: 36 ± 8.7 years). Country: Türkiye. | Demographic: Not reported. Socio-economic: Job loss, difficulties in social interaction, and deterioration of family relationships. Psycho-emotional: Depressive mood, aggression, feelings of despair. Physical: Not reported. | Develop training to improve suicide risk recognition and management. Nurses should systematically assess risk, promote effective communication, and support patients’ hope and spirituality. An institutional culture fostering prevention and timely psycho-social referrals is essential. |

| Men et al. [51] | Mixed study. Methods: Quantitative data were collected from reports prepared by the Hong Kong Coroner’s Court. Qualitative data collection involved a qualitative analysis of suicide notes using a grounded theory approach to identify and code motivations for suicide. | Period: 2012–2017 Sample: 551 individuals with a history of cancer (female: 34.12%; mean age: Not reported) Country: China | Demographic: Not reported. Socio-economic: Concerns related to work and social relationships. Psycho-emotional: Depression, anxiety, feelings of guilt and remorse. Physical: Associated physical discomfort. | The authors describe that suicide prevention should not only focus on the cancer patient but also on their family members and/or caregivers, providing follow-up services that offer emotional and social support. It is key that nurses address the mental, social, and physical needs, thereby delivering a holistic and comprehensive approach. |

| Senf, Maiwurm & Fettel [36] | Quantitative study. Methods: Quantitative data were collected using an online questionnaire consisting of 48 closed and open-ended questions, distributed via email. Quantitative data analysis was performed using IBM SPSS v.23.0. Qualitative data were evaluated through content analysis following Mayring’s method, using the software QCAmap. | Period: 2017–2018. Sample: 354 healthcare professionals working with cancer patients (female: 77.1%; mean age: 47.8 ± 11.5 years). Country: Germany. | Demographic: Not reported. Socio-economic: Social isolation. Psycho-emotional: Feelings of loss of control and autonomy, anxiety, depression. Physical: Pain, physical disability. | The authors highlight the importance of nurse training in communication and suicide risk management to effectively identify and support oncology patients at risk. Nurses should develop specialised knowledge and assessment skills and be able to refer patients to specialists when necessary. |

| Walker et al. [37] | Quantitative study. Methods: Data were collected through the Scottish National Health System Cancer Registry. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) was also administered. All data analyses were performed using Stata 16. | Period: 2008–2012. Sample: 2217 cancer patients with comorbid major depression (female: 80%; mean age: 60 ± 8 years). Country: United Kingdom. | Demographic: Young people. Socio-economic: Not reported. Psycho-emotional: Depression. Physical: Not reported. | The authors describe the need to implement depression screening programmes for the assessment and management of suicide risk in oncology patients. |

| Yang et al. [38] | Quantitative study. Methods: Data were collected using the following scales: IRI, CBI, SDS, SIS, and BSI. All data analyses were conducted using EpiData Entry version 3.1 and SPSS version 25.0. | Period: 2019–2021. Sample: 358 cancer patients (female: 52.51%; mean age: 55.2 ± 3.8 years). Country: China. | Demographic: Not reported. Socio-economic: Social stigma. Psycho-emotional: Insufficient self-efficacy, depressive symptoms. Physical: Not reported. | The authors emphasise the importance of personalised care that helps patients and families recognise their strengths, alongside psycho-social counselling, health education, and palliative care, when necessary, to improve quality of life and reduce suicide risk. |

| Granek et al. [44] | Qualitative study. Methods: In-depth interviews were conducted. Interview transcripts were analysed using line-by-line systematic coding following Grounded Theory principles to identify emerging themes. NVivo 10 software was used to organise, classify, and code the data in a structured manner. | Period: Not reported. Sample: 61 healthcare professionals (female: 32.79%; mean age: not described). Country: Israel. | Demographic: Not reported. Socio-economic: Lack of social support. Psycho-emotional: Emotional distress, hopelessness, history of prior mental disorders. Physical: Physical deterioration related to disease progression. | The authors highlight the following care measures: 1. Promoting communication with the patient to ensure greater sensitivity in the choice of words when interacting with the patient and their family, emphasising essential skills such as empathy and humanisation. 2. Monitoring warning signs, including body language and expressions or desires of death from patients. |

| Senf, Maiwurm & Fettel [39] | Quantitative Study Methods: Data were collected using a 48-item online questionnaire comprising both closed and open-ended questions, distributed via email. Quantitative data were analysed using SPSS version 23.0. Qualitative responses were assessed through content analysis following Mayring’s method, employing the QCAmap software. | Period: December 2017–February 2018. Sample: 354 healthcare professionals working with cancer patients (women: 77.1%; mean age: 47.8 ± 11.5 years). Country: Germany. | Demographic: Not reported. Socio-economic: Not reported. Psycho-emotional: Pre-existing psychiatric illness (depression), high levels of distress. Physical: Not reported. | The authors propose the following measures to improve care: (1) implement psycho-oncological training alongside additional education focused on managing suicidal tendencies; (2) introduce the KoMPASS programme, which centres on communication training to promote positive changes in nurses’ communicative behaviours and attitudes, thereby enhancing professional–patient communication. |

| Granek et al. [45] | Qualitative Study Methods: Grounded theory was employed to analyse interviews conducted with oncology nurses from two academic oncology centres in Israel. Categories were defined concerning the barriers encountered, therapeutic approaches, and perceptions regarding the management of psychological distress and suicidal behaviour. Software: NVivo 10. | Period: Not reported. Sample: 20 nurses (women: 100%; mean age: not reported). Country: Israel. | Demographic: Not reported. Socio-economic: Lack of availability and accessibility of mental health resources. Psycho-emotional: Stigma surrounding mental health care. Physical: Physical pain. | 1. Establish effective communication with key professionals (psychologists, social workers) to assess and manage suicide risk individually, providing early emotional support. 2. Promote continuous training on identifying and managing suicide risk, focusing on pain, distress, and suicidal thoughts. 3. Implement regular suicide risk assessments and tailored intervention protocols in oncology care. |

| Granek et al. [46] | Qualitative Study. Methods: Interviews were conducted using a grounded theory design. The analysis involved identifying emerging categories and patterns from the collected data. Software: NVivo 10. | Period: November 2015 to June 2016. Sample: 61 oncology health professionals (women: 32.79%; mean age: not reported). Country: Israel. | Demographics: Not reported. Socio-economic: Not reported. Psycho-emotional: Expression of distress, hopelessness, mental suffering. Physical: Physical suffering related to illness. | Training healthcare professionals in suicide risk detection and prevention using tools like PHQ-9 or BHS is essential. An ethical approach respecting patient autonomy and providing emotional support should be promoted. Creating spaces for professional reflection and ensuring early referral of at-risk patients to mental health specialists are also crucial. |

| Granek et al. [47] | Qualitative study. Methods: Individual, semi-structured, in-depth interviews were conducted using a grounded theory design. The sample was purposive and focused. NVivo 10 software was used for data management and analysis. | Period: Not reported. Sample: 61 oncology healthcare professionals (women: 32.79%; mean age: Not specified). Country: Israel. | Demographic: Not reported. Socio-economic: Lack of social support. Psycho-emotional: History of mental health disorders; hopelessness and perceived lack of meaning in life; difficulties coping with diagnosis and treatment. Physical: Chronic pain and functional decline. | Suicide risk should be assessed through direct questions about suicidal ideation and by recognising verbal and non-verbal signs. Creating a safe, empathetic environment that encourages emotional expression is essential. Additionally, documenting psychiatric history and offering coping strategies is important. Involving family members strengthens prevention and care. |

| Granek et al. [48] | Qualitative study. Methods: Interviews were conducted based on grounded theory. Categories were developed related to the understanding, assessment, and management of suicidal ideation, as well as factors influencing clinical decision-making and ethical judgment. NVivo 10 software was used. | Period: Not reported. Sample: 61 professionals [oncologists: 23; social workers: 18; nurses: 20] (women: 85.2%; mean age: 47.7 years). Country: Israel. | Demographic: Not reported. Socio-economic: Lack of social support. Psycho-emotional: Fear of being a burden, history of mental illness, delivering bad news. Physical: Physical pain and suffering, disease relapse or progression. | Nurses should identify signs of distress and suffering, as well as suicide risk. This involves conducting individualised assessments and enhancing training to promote coping techniques. They should also encourage open communication about death and patient wishes to identify potential risks, including involving the family in these discussions. Early intervention is recommended for at-risk patients. |

| Sun et al. [40] | Quantitative Study. Methods: Data were collected using the following scales: CES-D, BSI, and the World Health Organization Quality of Life Questionnaire. Data analysis was conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics. Independent t-tests were used to compare means of continuous variables, and the chi-square test was applied to compare categorical variables between two groups. | Period: September 2014–September 2015. Sample: 87 breast cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy (women: 100%; mean age: 54.1 ± 7.7 years). Country: China. | Demographics: Not reported. Socio-economic: Not reported. Psycho-emotional: Depression, hopelessness, mental exhaustion, pre-existing mental illness, and history of suicide attempts. Physical: Physical pain, physical deterioration due to disease progression. | Teach cancer patients muscle relaxation techniques and promote therapeutic walking to help reduce depression, improve quality of life, and alleviate physical pain and negative emotions. Additionally, other methods such as aromatherapy, behavioural activation therapy, and problem-solving therapy can be used. Training in beneficial exercise programs for these patients is also necessary. |

| Zhang et al. [49] | Qualitative Study. Methods: Individual face-to-face interviews were conducted. The data translation followed a back-translation procedure, and thematic analysis was performed according to Braun and Clarke. | Period: April to November 2014 Sample: 32 patients with stomach cancer (women: 15.6%; mean age: 56.8 years). Country: China. | Demographic: Not reported. Socio-economic: Caregiver fatigue and lack of social support. Psycho-emotional: Lack of coping skills and hopelessness. Physical: Physical problems due to poor treatment adherence. | Evaluate modifiable risk and protective factors in each patient by: (a) implementing protocols for suicide risk assessment and management, including appropriate training; (b) facilitating communication between patients and families to strengthen family support as a protective factor; and (c) coordinating with other professionals to provide comprehensive care. |

| Klaassen et al. [41] | Quantitative Study. Methods: Data were collected from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database and the National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4. | Period: 1988–2010. Sample: 1,178,000 bladder cancer patients (women: 286,001, 24.27%; mean age: not reported). Country: United States. | Demographic: Male sex, white race, age over 80, and single/divorced/widowed marital status. Socio-economic: Low socio-economic status. Psycho-emotional: History of psychiatric illness or abuse. Physical: Not reported. | The authors emphasise the importance of clinical professionals being aware of suicide risk factors in patients diagnosed with cancer and employing mental health intervention strategies to manage them effectively and improve quality of life. Nursing staff should conduct routine distress screenings for all patients to identify early signs and enhance psychological care. |

| Park, Chung & Lee [42] | Quantitative Study. Methods: Data were collected using structured questionnaires: Pain in advanced cancer patients, HADS, ECOG and Suicide Risk Assessment Subscale of the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI). Data analysis was performed using SPSS version 18.0. | Period: Not reported. Sample: 457 advanced cancer patients (women: 74.5%; mean age: not described). Country: South Korea. | Demographic: Not reported. Socio-economic: Not reported. Psycho-emotional: Anxiety. Physical: Physical pain. | The authors emphasise the need to identify and provide appropriate care for anxiety and severe physical pain, as these negatively impact the patient and lead to threatening stress levels that must be managed, given that stress increases suicide risk. In this regard, promoting the individual’s spiritual well-being serves a protective role in severe stress situations. |

| Lucas et al. [52] | Mixed Study. Methods: Qualitative data were collected through structured and semi-structured interviews with an open approach. Quantitative data were gathered using standardised scales (BSI and C-SSRS). Content analysis was performed on qualitative notes, and descriptive analysis was applied to quantitative data. | Period: Not reported. Sample: 186 mother caregivers and 134 adolescent and young adult survivors (mother caregivers—women: 100%; mean age: 49.4 years; survivors—women: 43.55%; mean age: 18.18 years). Country: United States. | Demographic: Adolescents and young adults. Single status. Low educational level. Socio-economic: Low family income, recent unemployment. Psycho-emotional: Psychological distress. Physical: Not reported. | Conduct comprehensive assessments of survivors based on suicide risk. Involve family members or caregivers, providing support and access to mental health professionals when needed. Train staff in assessment tools such as BSI and C-SSRS. Implement safety protocols for vulnerable populations experiencing psycho-social distress. |

4. Discussion

4.1. Characteristics of the Studies and the Sample

4.2. Demographic, Socio-Economic, Psycho-Emotional, and Physical-Factors Associated with Suicide Risk in Cancer Patients

4.3. Nursing Care to Reduce the Suicide Risk in Oncology Patients

- (1)

- Systematic suicide risk assessment: Validated tools such as the C-SSRS and the Plutchik Risk Scale are essential for early detection and continuous monitoring of suicide risk [31,33,34,35,36,37,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,52]. Clinical practice guidelines recommend applying these tools regularly—particularly after critical changes in diagnosis or psycho-social circumstances [35,48]. In nursing settings, this involves embedding screening into electronic health records and integrating assessments into routine consultations, as suggested by Gascón et al. [25] and Janes [69].

- (2)

- Professional training and communication skills development: Continuous professional development is crucial to improve nurses’ ability to recognise suicidal ideation, express empathy, and build trust with patients [35,36,39,40,43,44,45,46]. This education should be grounded in an understanding of associated risk factors and clear knowledge of appropriate response protocols [70,71]. Simulation-based training and structured communication models—such as KoMPASS—have demonstrated success in improving detection and intervention rates in clinical settings. From a practice standpoint, this means institutional investment in annual suicide prevention workshops, role-play exercises, and the creation of ethical guidelines for addressing existential distress [39]. Richard et al. [71] highlight the importance of simulation as a pedagogical tool in enhancing confidence and competence in suicide risk management.

- (3)

- Therapeutic and supportive nursing interventions: Interventions such as progressive muscle relaxation, therapeutic walking, aromatherapy, and problem-solving therapy reduce distress and improve patient well-being. Nurses can incorporate these into individualised care plans, especially in palliative and chemotherapy settings where physical symptoms and emotional fatigue often co-occur [40,43,45]. Liu et al. [72] confirm that aromatherapy via inhalation significantly decreases anxiety and depression levels in cancer patients, while Bosman et al. [73] show the utility of art-based interventions in supportive care.

- (4)

- Integration into routine clinical practice and interdisciplinary coordination: Risk detection protocols are most effective when integrated into daily nursing documentation and shift handovers. Collaboration with mental health professionals and social workers is vital to ensure rapid intervention in high-risk cases. In clinical terms, this translates to clear referral pathways, shared decision-making protocols, and multidisciplinary case reviews [35,41,46]. Studies outside the review support these findings, emphasising the importance of multidimensional care, particularly during times when patients may have more complex or shifting needs [73,74]. Kobayakawa et al. [75] advocate for the inclusion of mental health specialists early in the care continuum to address emotional crises and coordinate support for both patients and families.

- (5)

- Family and caregiver support: Suicide prevention must extend beyond the patient to include family members and caregivers, who may also be experiencing psychological distress. Nurses should be trained to screen caregivers for burden and emotional fatigue, facilitate emotional support sessions, and provide referrals to psychological services when needed [32,38,47,48,49,50,51,52]. Lucas et al. [52] demonstrate the effectiveness of caregiver support in reducing distress and improving long-term psycho-social outcomes. In practice, this can involve family-centred care plans, psycho-educational materials, and structured communication strategies to reinforce the family’s protective role.

4.4. Key Implications for Clinical Practice, Health Policy, and Future Research

- (1)

- Relevance for clinical nursing practice: 1. Incorporate validated tools such as the Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS) and the Plutchik Suicide Risk Scale into routine nursing assessments for systematic suicide risk screening [31,35,44,48,50,52]. 2. Promote non-pharmacological nursing interventions—such as progressive muscle relaxation, therapeutic walking, and aromatherapy—to alleviate physical and emotional distress [40,43,45]. 3. Strengthen empathic communication and patient-centred care through active listening, identification of distress signals, and therapeutic nurse–patient relationships [23,39,44,47].

- (2)

- Implications for institutional and health policy: 1. Develop and implement ongoing professional training programmes on suicide prevention, including communication skills, ethical protocols, and clinical simulation methods (e.g., the KoMPASS programme) [35,39,45]. 2. Integrate suicide risk screening into electronic nursing documentation and standardise referral pathways through interdisciplinary coordination with mental health professionals and social workers [35,41,45,46].

- (3)

- Priorities for future research: 1. Conduct controlled studies to evaluate the effectiveness of specific nursing interventions—such as relaxation techniques, family support strategies, and structured psycho-social care—in suicide prevention [32,43,45,52]. 2. Undertake longitudinal research to identify high-risk periods across the cancer care continuum, especially among adolescents, young adults, and caregivers [37,52]. Explore the cultural adaptability and global applicability of these nursing approaches by including under-represented populations and diverse healthcare systems [19,34].

4.5. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Public Involvement Statement

Guidelines and Standards Statement

Use of Artificial Intelligence

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Red Española de Registros de Cáncer. Estimaciones de la Incidencia de Cáncer en España. Available online: https://redecan.org/storage/documentation/442e1d1a-4040-4674-81cf-5e6a67af6458.pdf (accessed on 15 February 2025).

- Sociedad Española de Oncología Médica. El Cáncer en Cifras. Available online: https://seom.org/publicaciones/el-cancer-en-espanyacom (accessed on 14 February 2025).

- Fang, F.; Fall, K.; Mittleman, M.A.; Sparén, P.; Ye, W.; Adami, H.; Valdimarsdóttir, U. Suicide and Cardiovascular Death after a Cancer Diagnosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 366, 1310–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heinrich, M.; Hofmann, L.; Baurecht, H.; Kreuzer, P.M.; Knüttel, H.; Leitzmann, M.F.; Seliger, C. Suicide Risk and Mortality Among Patients with Cancer. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 852–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turecki, G.; Brent, D.A.; Gunnell, D.; O’Connor, R.C.; Oquendo, M.A.; Pirkis, J.; Stanley, B.H. Suicide and suicide risk. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2019, 5, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahn, M.H.; Park, S.; Lee, H.B.; Ramsey, C.M.; Na, R.; Kim, S.O.; Kim, J.E.; Yoon, S.; Hong, J.P. Suicide in cancer patients within the first year of diagnosis. Psycho-Oncol. 2015, 24, 601–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, C.; Park, E.M.; Rosenstein, D.L.; Nichols, H.B. Suicide rates among patients with cancers of the digestive system. Psycho-Oncol. 2018, 27, 2274–2280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, D.; Renshaw, C.; Okello, C.; Møller, H.; Davies, E.E. Suicide in cancer patients in South East England from 1996 to 2005: A population-based study. Br. J. Cancer 2009, 101, 198–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vyssoki, B.; Gleiss, A.; Rockett, I.R.H.; Hackl, M.; Leitner, B.; Sonneck, G.; Kapusta, N.D. Suicide among 915,303 Austrian cancer patients: Who is at risk? J. Affect. Disord. 2015, 175, 287–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaorsky, N.G.; Zhang, Y.; Tuanquin, L.; Bluethmann, S.M.; Park, H.S.; Chinchilli, V.M. Suicide among cancer patients. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avci, D.; Selcuk, K.T.; Dogan, S. Suicide risk in the hospitalized elderly in Turkey and affecting factors. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2017, 31, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, L.; Lin, C.; Shen, W.; Kao, C. Suicide attempts in patients with head and neck cancer in Taiwan. Psycho-Oncol. 2020, 29, 1026–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, L.; Shi, H.Y.; Yu, H.R.; Liu, X.M.; Jin, X.H.; Yan, Q.; Fu, X.L.; Song, Y.P.; Cai, J.Y.; Chen, H.L. Incidence of suicide death in patients with cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 276, 711–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henriques, F.; Almada, A.L.; Monteiro, L. Oncology and suicide. Psicosomática Psiquiatr. 2018, 7, 50–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFarland, D.C.; Walsh, L.; Napolitano, S.; Morita, J.; Jaiswal, R. Suicide in Patients with Cancer: Identifying the Risk Factors. Cancer Netw. 2019, 33, 221–226. [Google Scholar]

- Stanton, A.L.; Danoff-Burg, S.; Cameron, C.L.; Bishop, M.; Collins, C.A.; Kirk, S.B.; Sworowski, L.A.; Twillman, R. El afrontamiento emocionalmente expresivo predice el ajuste psicológico y físico al cáncer de mama. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2000, 68, 875–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mann, J.J.; Apter, A.; Bertolote, J.; Beautrais, A.; Currier, D.; Haas, A.; Hegerl, U.; Lonnqvist, J.; Malone, K.; Marusic, A.; et al. Suicide prevention strategies: A systematic review. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2005, 294, 2064–2074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arenas, P.; Lucio, E.; Forns, M. Indicadores diferenciales de personalidad frente al riesgo de suicidio en adolescentes. Rev. Iberoam. Diagnóstico Evaluación—Avaliação Psicológica 2012, 1, 51–74. [Google Scholar]

- Organización Mundial de la Salud. Preventing Suicide. A Global Imperative; World Health Organization: Geneve, Switzerland; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241564779 (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Campus Mexicali. La Familia es Fundamental en la Prevención y Recuperación del Riesgo Suicida. Available online: https://www.cetys.mx/noticias/la-familia-es-fundamental-en-la-prevencion-y-recuperacion-del-riesgo-suicida/#:~:text=La%20familia%20es%20una%20red,seres%20queridos%2C%20concluy%C3%B3%20el%20psic%C3%B3logo (accessed on 5 March 2025).

- Díaz de Flores, L.; de Villalobos, M.M.D.; de Pardo, P.G.; Daza, B.G.; de Obando, E.G.; de Acuña, Y.G.; del Carmen Gutiérrez de Giraldo, M.; Posada, Á.H.; Maya, J.C.L.; Fergusson, M.E.M.; et al. Análisis de los Conceptos del Modelo de Adaptación de Callista Roy. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=2107433 (accessed on 9 March 2025).

- García, J.; García, H.; Blanco de Tena, E.; Martínez, M.; Aranguren, P. Más allá del modelo biomédico: El enfoque existencial-contextual de la conducta suicida. Panor. Soc. 2023, 38, 53–69. [Google Scholar]

- Öztürk, S.; Hiçdurmaz, D. Desarrollo y evaluación psicométrica de la escala de percepción de eficacia para la gestión del riesgo de suicidio en enfermeras oncológicas. Semin. Enfermería Oncológica 2024, 40, 151740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledo, V. El Suicidio en Pacientes Con Cáncer y su Abordaje Desde Enfermería. Una Revisión Bibliográfica. Trabajo Fin de Grado, Universidad de Valladolid. Available online: https://uvadoc.uva.es/bitstream/handle/10324/42073/TFG-H1813.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 24 February 2025).

- Gascón, B.; Leung, Y.; Espin-Garcia, O.; Rodin, G.; Chu, D.; Li, M. Suicide Risk Screening and Suicide Prevention in Patients with Cancer. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2021, 5, pkab057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolva, E.; Hoffecker, L.; Cox-Martin, E. Suicidal ideation in patients with cancer: A systematic review of prevalence, risk factors, intervention and assessment. Palliat. Support. Care 2020, 18, 206–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valente, S.M. Oncology nurses’ teaching and support for suicidal patients. J. Psychosoc. Oncol. 2007, 25, 121–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urrútia, G.; Bonfill, X. Declaración PRISMA: Una propuesta para mejorar la publicación de revisiones sistemáticas y metaanálisis. Med. Clínica 2010, 135, 507–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Pino, R.; Frías, A.; Palomino, P.A. La revisión sistemática cuantitativa en enfermería. Rev. Iberoam. Enferm. Comunitaria 2014, 7, 24–39. [Google Scholar]

- Perestelo-Pérez, L. Standards on how to develop and report systematic reviews in Psychology and Health. Int. J. Clin. Health Psychol. 2013, 13, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espuig, A.; Pons-Vinent, M.; Carbajo, E.; Lacomba-Trejo, L. The Impact of Pain, Threat Perception and Emotional Distress on Suicide Risk in Individuals with Colorectal Cancer. Nurs. Rep. 2024, 14, 2629–2639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Ding, X.; Liu, Y.; Han, Y.; Wang, G.; Cai, M.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, D.Y. The Relationship Between Social Support and Suicide Resilience in Chinese Cancer Patients: A Serial Multiple Mediation Model Through Self-care Self-efficacy and Meaning in Life. Cancer Nurs. 2024, 47, 236–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, B.; Zhu, N.; Yu, M.; Guan, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Deng, Y.; Jiang, Y. Single Question for Screening Suicide Risk in Patients with Cancer in Nursing Routine Work: A Retrospective Cross-Sectional Study. J. Adv. Nurs. 2025, 81, 4627–4643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, X.; Ma, J.; Jemal, A.; Zhao, J.; Nogueira, L.; Ji, X.; Yabroff, K.R.; Han, X. Suicide Risk Among Individuals Diagnosed with Cancer in the US, 2000–2016. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e2251863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katayama, E.S.; Moazzam, Z.; Woldesenbet, S.; Lima, H.A.; Endo, Y.; Azap, L.; Yang, J.; Dillhoff, M.; Ejaz, A.; Cloyd, J.; et al. Suicidal Ideation Among Patients with Gastrointestinal Cancer. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2023, 30, 3929–3938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senf, B.; Maiwurm, P.; Fettel, J. Attitudes and opinions towards suicidality in professionals working with oncology patients: Results from an online survey. Support. Care Cancer 2022, 30, 1775–1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, J.; Magill, N.; Rosenstein, D.L.; Frost, C.; Sharpe, M. Suicidal Thoughts in Patients with Cancer and Comorbid Major Depression: Findings from a Depression Screening Program. J. Acad. Consult.-Liaison Psychiatry 2022, 63, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, N.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Wang, F.; Yang, G.; Hu, X. Influence of Social Workers’ Empathy Ability on Suicidal Ideation of Cancer Patients. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 925307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senf, B.; Maiwurm, P.; Fettel, J. Exposure to suicidality in professionals working with oncology patients: An online survey. Psycho-Oncol. 2020, 29, 1620–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, F.K.; Hung, C.M.; Yao, Y.; Lu, C.Y.; Chiang, C.Y. The Effects of Muscle Relaxation and Therapeutic Walking on Depression, Suicidal Ideation, and Quality of Life in Breast Cancer Patients Receiving Chemotherapy. Cancer Nurs. 2017, 40, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klaassen, Z.; DiBianco, J.M.; Jen, R.P.; Harper, B.; Yaguchi, G.; Reinstatler, L.; Woodard, C.; Moses, K.A.; Terris, M.K.; Madi, R. The Impact of Radical Cystectomy and Urinary Diversion on Suicidal Death in Patients with Bladder Cancer. J. Wound Ostomy Cont. Nurs. 2016, 43, 152–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.A.; Chung, S.H.; Lee, Y. Factors Associated with Suicide Risk in Advanced Cancer Patients: A Cross-Sectional Study. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2016, 17, 4831–4836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Öztürk, S.; Hiçdurmaz, D. A qualitative study on the perspectives and needs of oncology nurses about recognition and management of suicide risk in cancer patients. J. Clin. Nurs. 2023, 32, 749–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Granek, L.; Nakash, O.; Shapira, S.; Ariad, S.; Ben-David, M.A. Oncologists, oncology nurses and oncology social workers experiences with suicide: Impact on patient care. J. Psychosoc. Oncol. 2020, 38, 543–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Granek, L.; Nakash, O.; Ariad, S.; Shapira, S.; Ben-David, M. Strategies and Barriers in Addressing Mental Health and Suicidality in Patients with Cancer. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 2019, 46, 561–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Granek, L.; Nakash, O.; Ariad, S.; Shapira, S.; Ben-David, M. Oncology healthcare professionals’ perceptions, explanatory models, and moral views on suicidality. Support. Care Cancer 2019, 27, 4723–4732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Granek, L.; Nakash, O.; Ben-David, M.; Shapira, S.; Ariad, S. Oncologists’, nurses’, and social workers’ strategies and barriers to identifying suicide risk in cancer patients. Psycho-Oncol. 2018, 27, 148–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Granek, L.; Nakash, O.; Ariad, S.; Chen, W.; Birenstock-Cohen, S.; Shapira, S.; Ben-David, M. From will to live to will to die: Oncologists, nurses, and social workers identification of suicidality in cancer patients. Support. Care Cancer 2017, 25, 3691–3702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.K.; Procter, N.G.; Xu, Q.; Chen, X.Y.; Lou, F.L. Factors influencing suicidal ideation among Chinese patients with stomach cancer: Qualitative study. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2017, 64, 413–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwinn, T.; Hirschmiller, J.; Wiltink, J.; Zwerenz, R.; Brähler, E.; Beutel, M.E.; Ernst, M. Practitioners’ perspective: A mixed-methods study on dealing with suicidality from the perspective of oncological healthcare professionals. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2025, 151, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Men, Y.V.; Yeung, C.Y.; Lam, T.C.; Fai Yip, P.S.; Emery, C.R. Using suicide notes to understand suicide among cancer patients: A mixed-method study. Psycho-Oncol. 2022, 31, 614–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucas, M.S.; Brawner, B.M.; Hardie, T.L.; Beacham, B.; Paidipati, C.; Diaz, M.; Lauer, A.; Hobbie, W.L.; Deatrick, J.A. Assessing Suicidal Ideation and Behaviors Among Survivors of Childhood Brain Tumors and Their Mothers During Sociobehavioral Research. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 2015, 42, 319–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gimeno, J.; Sánchez, R.; Esteve, A.; Gómez, S.; Miranda, I.; Zaragoza, L. Estudio cualitativo fenomenológico sobre el impacto emocional del diagnóstico del cáncer y efectos secundarios del tratamiento de quimioterapia. Rev. Sanit. Investig. 2022, 3, 194. [Google Scholar]

- Niedzwiedz, C.L.; Knifton, L.; Robb, K.A.; Katikireddi, S.V.; Smith, D.J. Depression and anxiety among people living with and beyond cancer: A growing clinical and research priority. BMC Cancer 2019, 19, 943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernández, R.; Fernández, C.; Baptista, P. Metodología de la Investigación, 6th ed.; McGraw-Hill: Mexico, México, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Carreira, H.; Williams, R.; Müller, M.; Harewood, R.; Stanway, S.; Bhaskaran, K. Associations Between Breast Cancer Survivorship and Adverse Mental Health Outcomes: A Systematic Review. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2018, 110, 1311–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linden, W.; Vodermaier, A.; MacKenzie, R.; Greig, D. Anxiety and depression after cancer diagnosis: Prevalence rates by cancer type, gender, and age. J. Affect. Disord. 2012, 141, 343–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hem, E.; Loge, J.H.; Haldorsen, T.; Ekeberg, O. Riesgo de suicidio en pacientes con cáncer de 1960 a 1999. J. Clin. Oncol. 2004, 22, 4209–4216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kendal, W.S. Suicidio y cáncer: Un estudio comparativo de género. Soc. Eur. Oncol. Médica 2007, 18, 381–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vehling, S.; Lehmann, C.; Oechsle, K.; Bokemeyer, C.; Krüll, A.; Koch, U.; Mehnert, A. Significado global y actitudes vitales relacionadas con el significado: Exploración de su papel en la predicción de la depresión, la ansiedad y la desmoralización en pacientes con cáncer. Support. Care Cancer 2011, 19, 513–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yousaf, U.; Christensen, M.L.; Engholm, G.; Storm, H. Suicidios en pacientes con cáncer daneses, 1971–1999. Br. J. Cancer 2005, 92, 995–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michalek, I.M.; Caetano Dos Santos, F.L.; Wojciechowska, U.; Didkowska, J. Suicide risk among adolescents and young adults after cancer diagnosis: Analysis of 34 cancer groups from 2009 to 2019. J. Cancer Surviv. Res. Pract. 2023, 17, 657–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heynemann, S.; Thompson, K.; Moncur, D.; Silva, S.; Jayawardana, M.; Lewin, J. Risk factors associated with suicide in adolescents and young adults (AYA) with cancer. Cancer Med. 2021, 10, 7339–7346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osazuwa-Peters, N.; Simpson, M.C.; Zhao, L.; Boakye, E.A.; Olomukoro, S.I.; Deshields, T.; Loux, T.M.; Varvares, M.A.; Schootman, M. Suicide risk among cancer survivors: Head and neck versus other cancers. Cancer 2018, 124, 4072–4079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darvishi, N.; Farhadi, M.; Poorolajal, J. The role of social support in preventing suicidal ideations and behaviors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Res. Health Sci. 2024, 24, e00609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahn, G.D.; Tam, S.H.; Felton, J.W.; Westphal, J.; Simon, G.E.; Owen-Smith, A.A.; Rossom, R.C.; Beck, A.L.; Lynch, F.L.; Daida, Y.G.; et al. Cancer and psychiatric diagnoses in the year preceding suicide. Cancer Med. 2022, 12, 3601–3609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cianci, F. Suicidal events in cancer patients and the importance of an early prevention: A narrative review. La Clin. Ter. 2024, 175, 123–129. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, C.; Wang, L.; Wang, X. Effects of physical and psychological symptoms on cancer-related fatigue among esophageal cancer patients. BMC Cancer 2024, 24, 398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janes, T. How can a suicide screening and prevention procedure be implemented in a cancer center? Clin. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2018, 22, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Granek, L.; Nakash, O. Prevalence and risk factors for suicidality in cancer patients and oncology healthcare professionals strategies in identifying suicide risk in cancer patients. Curr. Opin. Support. Palliat. Care 2020, 14, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richard, O.; Jollant, F.; Billon, G.; Attoe, C.; Vodovar, D.; Piot, M.A. Simulation training in suicide risk assessment and intervention: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Med. Educ. Online 2023, 28, 2199469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, T.; Cheng, H.; Tian, L.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, S.; Lin, L. Aromatherapy with inhalation can effectively improve the anxiety and depression of cancer patients: A meta-analysis. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2022, 77, 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bosman, J.T.; Bood, Z.M.; Scherer-Rath, M.; Dörr, H.; Christophe, N.; Sprangers, M.A.G.; Van Laarhoven, H.W.M. The effects of art therapy on anxiety, depression, and quality of life in adults with cancer: A systematic literature review. Support. Care Cancer 2021, 29, 2289–2298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamal, A.H.; Warraich, H.J. Advanced Analytics as an Accelerator for Palliative Care and Oncology Integration. JCO Oncol. Pract. 2021, 18, 11–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobayakawa, M.; Ogawa, A.; Konno, M.; Kurata, A.; Hamano, J.; Morita, T.; Kizawa, Y.; Tsuneto, S.; Shima, Y.; Aoyama, M.; et al. Psychological and psychiatric symptoms of terminally ill patients with cancer and their family caregivers in the home-care setting: A nation-wide survey from the perspective of bereaved family members in Japan. J. Psychosom. Res. 2017, 103, 127–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molina-Azorin, J.F. Misex methods research: An opportunity to improve our studies and our research skills. Eur. J. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2016, 25, 37–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, K.; Chimoriya, R. A guide to a Mised-Methods Approach to Healthcare Research. Encyclopedia 2025, 5, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirmayer, L.J. Suicide in cultural context: An ecosocial approach. Transcult. Psychiatry 2022, 59, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Borrallo-Riego, Á.; García-Mayo, M.; Gil-Ordóñez, I.; Domínguez-Sánchez, I.; Guerra-Martín, M.D. Nursing Care to Reduce Suicide Risk in Cancer Patients: A Narrative Review of the Literature. Nurs. Rep. 2025, 15, 265. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15080265

Borrallo-Riego Á, García-Mayo M, Gil-Ordóñez I, Domínguez-Sánchez I, Guerra-Martín MD. Nursing Care to Reduce Suicide Risk in Cancer Patients: A Narrative Review of the Literature. Nursing Reports. 2025; 15(8):265. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15080265

Chicago/Turabian StyleBorrallo-Riego, Álvaro, María García-Mayo, Irene Gil-Ordóñez, Isabel Domínguez-Sánchez, and María Dolores Guerra-Martín. 2025. "Nursing Care to Reduce Suicide Risk in Cancer Patients: A Narrative Review of the Literature" Nursing Reports 15, no. 8: 265. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15080265

APA StyleBorrallo-Riego, Á., García-Mayo, M., Gil-Ordóñez, I., Domínguez-Sánchez, I., & Guerra-Martín, M. D. (2025). Nursing Care to Reduce Suicide Risk in Cancer Patients: A Narrative Review of the Literature. Nursing Reports, 15(8), 265. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15080265