Uncovering the Professional Landscape of Clinical Research Nursing: A Scoping Review with Data Mining Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

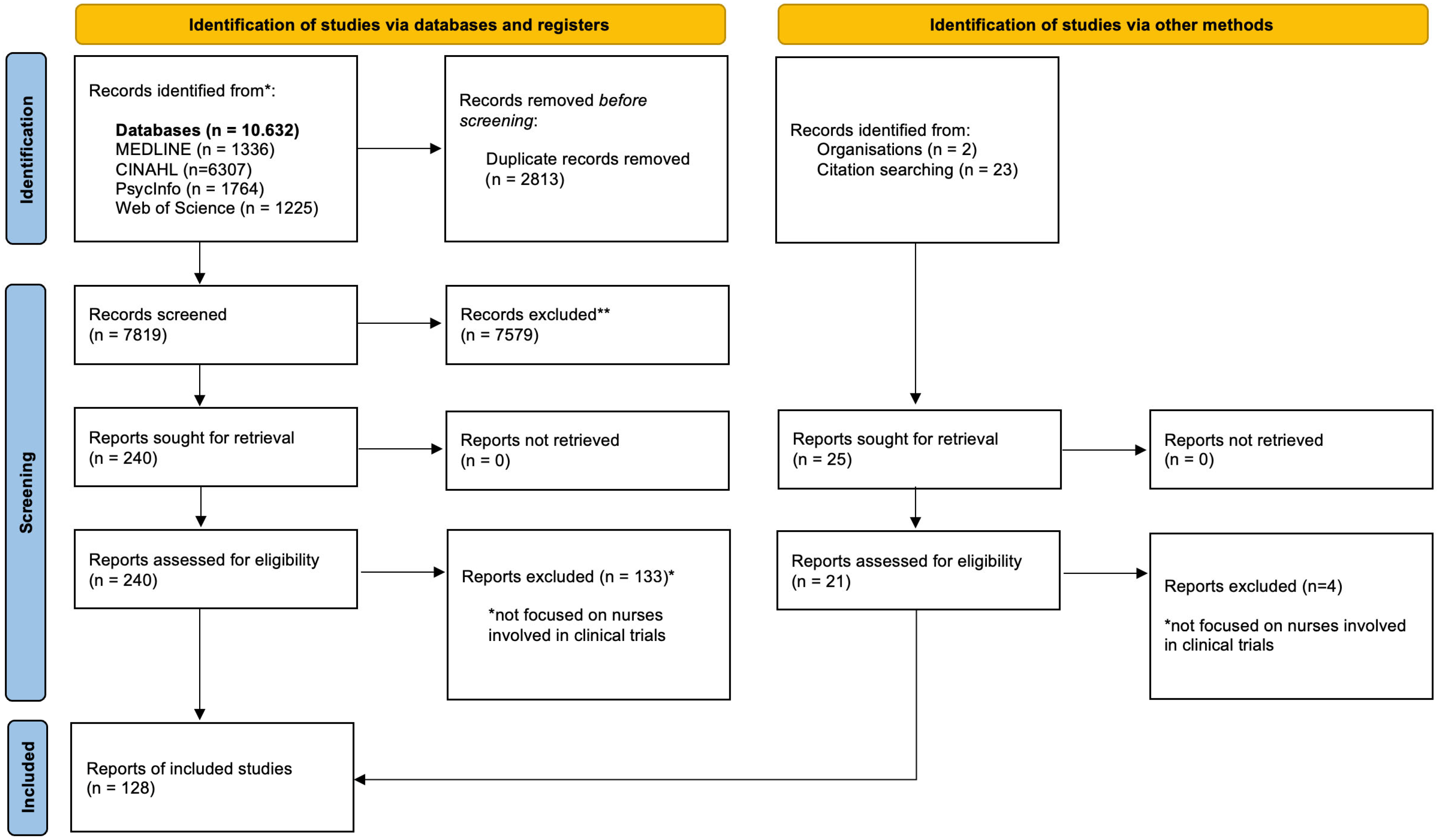

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Research Questions

2.3. Population, Context, and Concept

2.4. Eligibility Criteria

2.5. Search Strategy

2.6. Study Selection Process

2.7. Data Extraction

2.8. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Scope of Practice of CRNs (RQ1)

Role Perception, Integration, and Professional Recognition

3.2. Core Competences of CRNs (RQ2)

3.2.1. Formalization of Competencies and Reference Frameworks

3.2.2. Career Stagnation and Mismatch Between Skills and Professional Advancement

3.3. Obstacles Linked to the Position of CRNs (RQ3)

3.3.1. Ethical Tensions in Care Delivery and Trial Implementation

3.3.2. Organizational Barriers and Operational Constraints

3.4. Current Employment Status of CRNs Worldwide (RQ4)

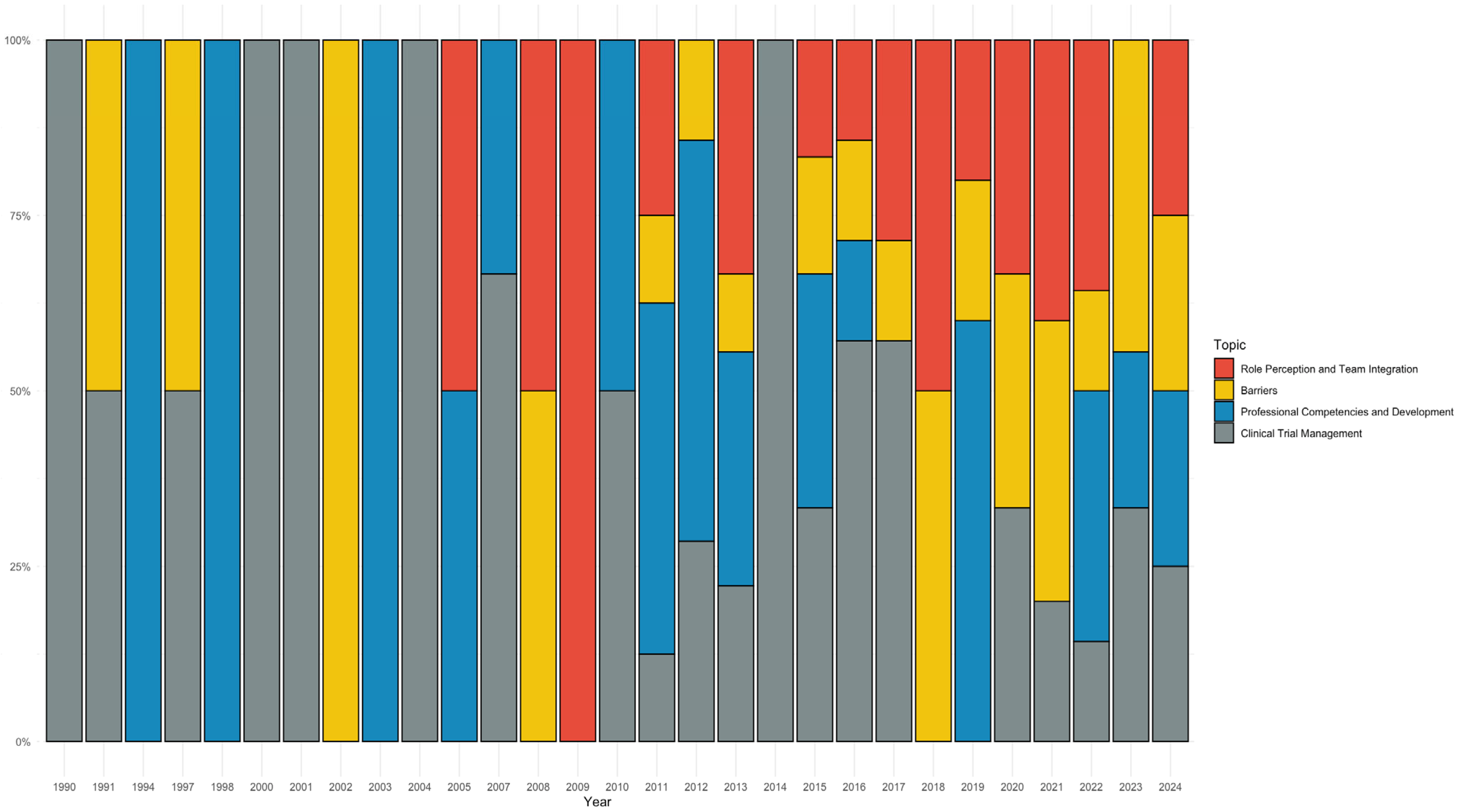

3.5. Geographical and Temporal Patterns in the CRN Literature (RQ5 and RQ9)

3.6. Clinical and Organizational Settings in Which the Crn Role Has Been Implemented (RQ6)

3.7. Outcomes Used to Study the Impact of the CRN Role (RQ7)

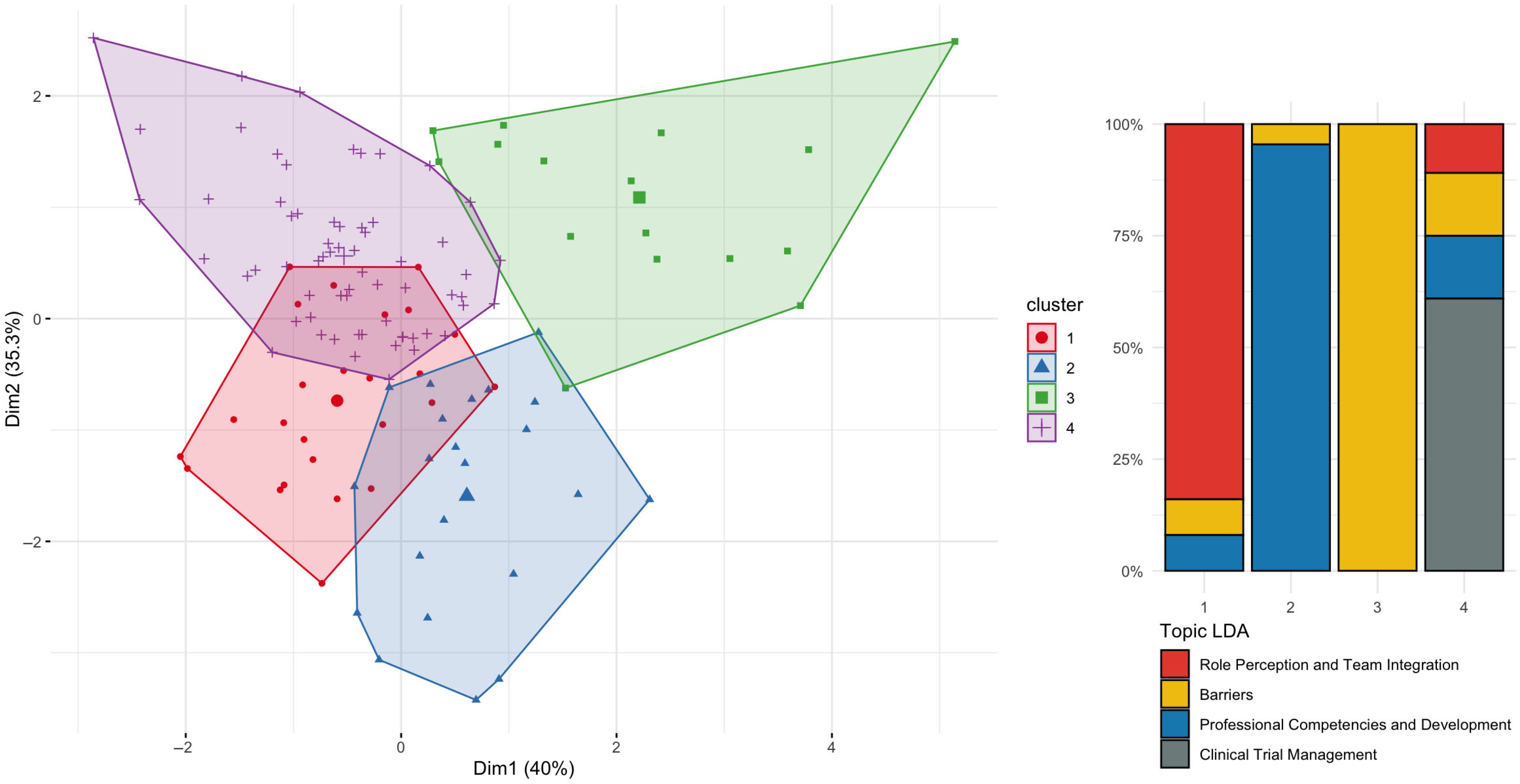

3.8. Temporal Patterns and Emerging Themes in the Literature (RQ9)

4. Discussion

4.1. Research Gaps and Reccomendations

4.2. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Public Involvement Statement:

Guidelines and Standards Statement:

Use of Artificial Intelligence:

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CRN | Clinical Research Nurse |

| SCR | Scoping Review |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| LDA | Latent Dirichlet Allocation |

| MCA | Multiple Correspondence Analysis |

References

- Gumber, L.; Agbeleye, O.; Inskip, A.; Fairbairn, R.; Still, M.; Ouma, L.; Lozano-Kuehne, J.; Bardgett, M.; Isaacs, J.D.; Wason, J.M.; et al. Operational complexities in international clinical trials: A systematic review of challenges and proposed solutions. BMJ Open 2024, 14, e077132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Nurses Association; International Association of Clinical Research Nursing. Clinical Research Nursing: Scope and Standards of Practice; American Nurses Association: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Society, O.N. Oncology Clinical Research Nurse Competencies. 2024. Available online: https://www.ons.org/oncology-clinical-research-nurse-competencies?utm_campaign=Clinical&utm_content=315308688&utm_medium=social&utm_source=linkedin&hss_channel=lcp-359947 (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Fox, R.C. Experiment Perilous: Physicians and Patients Facing the Unknown; Transaction Publishers: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Mayrink, N.N.V.; Alcoforado, L.; Chioro, A.; Fernandes, F.; Lima, T.S.; Camargo, E.B.; Valentim, R.A.M. Translational research in health technologies: A scoping review. Front. Digit. Health 2022, 4, 957367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastings, C.E.; Fisher, C.A.; McCabe, M.A. Clinical research nursing: A critical resource in the national research enterprise. Nurs. Outlook 2012, 60, 149–156.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinney, J.; Vermeulen, W. Research nurses play a vital role in clinical trials. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 2000, 27, 28. [Google Scholar]

- McEvoy, M.D.; Cannon, L.; MacDermott, M.L. The professional role for nurses in clinical trials. Semin. Oncol. Nurs. 1991, 7, 268–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Giulio, P.; Arrigo, C.; Gall, H.; Molin, C.; Nieweg, R.; Strohbucker, B. Expanding the role of the nurse in clinical trials: The nursing summaries. Cancer Nurs. 1996, 19, 343–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bevans, M.; Hastings, C.; Wehrlen, L.; Cusack, G.; Matlock, A.M.; Miller-Davis, C.; Tondreau, L.; Walsh, D.; Wallen, G.R. Defining clinical research nursing practice: Results of a role delineation study. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2011, 4, 421–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro, K.; Bevans, M.; Miller-Davis, C.; Cusack, G.; Loscalzo, F.; Matlock, A.M.; Mayberry, H.; Tondreau, L.; Walsh, D.; Hastings, C. Validating the clinical research nursing domain of practice. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 2011, 38, E72–E80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gwede, C.K.; Johnson, D.J.; Roberts, C.; Cantor, A.B. Burnout in clinical research coordinators in the United States. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 2005, 32, 1123–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Marnie, C.; Tricco, A.C.; Pollock, D.; Munn, Z.; Alexander, L.; McInerney, P.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H. Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evid. Synth. 2020, 18, 2119–2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.K.K.; O’Brien Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; Hempel, S.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Int. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruso, R.; Conte, G.; Arcidiacono, M.A.; Caponetti, S.; Cremona, G.; Dabbene, M.; Guberti, M.; Piredda, A.; Magon, A. Shaping the future research agenda of Cancer Nursing in Italy: Insights and strategic directions. J. Cancer Policy 2024, 42, 100505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Team, R.C. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Moor, N. Nikita-Moor/Ldatuning. 2023. Available online: https://github.com/nikita-moor/ldatuning (accessed on 21 March 2025).

- Arun, R.; Suresh, V.; Madhavan, C.E.V.; Murthy, M.N.N. On Finding the Natural Number of Topics with Latent Dirichlet Allocation: Some Observations; Springer Berlin: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 391–402. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, J.; Xia, T.; Li, J.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, S. A density-based method for adaptive LDA model selection. Neurocomputing 2009, 72, 1775–1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deveaud, R.; SanJuan-Ibekwe, E.; Bellot, P. Accurate and effective latent concept modeling for ad hoc information retrieval. Doc. Numérique 2014, 17, 61–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, T.L.; Steyvers, M. Finding scientific topics. Proc Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101 (Suppl. S1), 5228–5235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjellbrekke, J. Multiple Correspondence Analysis for the Social Sciences; Routledge Taylor & Francis Group: Abingdon, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Alsleben, A.R.; Alexander, J.L.; Matthews, E.P. Clinical Research Nursing: Awareness and Understanding Among Baccalaureate Nursing Students. J. Nurs. Educ. 2018, 57, 598–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beer, K.; Gentgall, M.; Templeton, N.; Whitehouse, C.; Straiton, N. Who’s included? The role of the Clinical Research Nurse in enabling research participation for under-represented and under-served groups. J. Res. Nurs. 2022, 27, 143–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capili, B.; Baker, L.; Thangthaeng, N.; Legor, K.; Larkin, M.E.; Jones, C.T. Development and evaluation of a clinical research nursing module for undergraduate nursing schools: Expanding Clinical Research Nurses’ outreach. J. Res. Nurs. 2022, 27, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, F.; Zhu, Q.; Wang, S.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, L.; Pan, R. The Role and Function of Clinical Research Nurses in Anti-tumor Drug Clinical Trials for Lung Cancer Patients. Chin. J. Lung Cancer 2008 2022, 25, 501–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubejko, B.; Good, M.; Weiss, P.; Schmieder, L.; Leos, D.; Daugherty, P. Oncology Clinical Trials Nursing. Clin. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2011, 15, 637–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martucci, M.; Guarrera, A.; Valente, D.; Resente, F.; Cagnazzo, C. Clinical research nurse in italian centers: A mandatory figure? Recent. Prog. Med. 2020, 111, 535–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Showalter, B.L.; Cline, D.; Yungclas, J.; La Frentz, K.; Stafford, S.R.; Maresh, K.J. Clinical Research Nursing: Development of a residency program. Clin. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2017, 21, 633–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Showalter, B.L.; Malecha, A.; Cesario, S.; Clutter, P. Moral distress in clinical research nurses. Nurs. Ethics 2022, 29, 1697–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirapelli, B.; Santos, S.S.D.; Kupper, B.E.C.; Nobrega, A.A.F.D. Research nurses contributions to research practice: An oncology nursing experience in Brazil. Appl. Cancer Res. 2018, 38, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cline, D.; Showalter, B. Research Nurse Residency: New Registered Nurses Transition to the Role of a Clinical Trials Nurse. Asia-Pac. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2020, 7, 229–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, H.A.; Wilson, J.; McInerney, V.; Kelsey, M.; Foley, J.; Moloney, M.C.; Irish Research Nurses Network (IRNN). Initial Report from the 2017–2018 Irish Research Nurses Network Survey on Research Nurses & Midwives. 2018, pp. 1–15. Available online: https://irnm.ie/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Initial-Report-from-the-2017-2018-Irish-Research-Nurses-Network-Survey-on-Research-Nurses-Midwives.pdf (accessed on 3 February 2025).

- Jones, H.C. Clinical research nurse or nurse researcher? Nurs. Times 2015, 111, 12–14. [Google Scholar]

- McNiven, A.; Boulton, M.; Locock, L.; Hinton, L. Boundary spanning and identity work in the clinical research delivery workforce: A qualitative study of research nurses, midwives and allied health professionals in the National Health Service, United Kingdom. Health Res. Policy Syst. 2021, 19, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, G.; Ellis, M.; Irvine, L. Duality of practice in clinical research nursing. J. Res. Nurs. 2022, 27, 116–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunhunny, S.; Salmon, D. The evolving professional identity of the clinical research nurse: A qualitative exploration. J. Clin. Nurs. 2017, 26, 5121–5132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlow, C.; Farrar, H.M. The role of the clinical trial nurse in Oklahoma. Okla. Nurse 2013, 58, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Best, I. Central role of the research nurse in improving accrual of older persons to cancer treatment trials. J. Clin. Oncol. 2005, 23, 7752, author reply 7752–7753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brearley, S. Diabetes research nursing. Study recruitment is the biggest challenge for the diabetes research nurse. J. Diabetes Nurs. 2013, 17, 197–198. [Google Scholar]

- Hemingway, B.; Storey, C. Role of the clinical research nurse in tissue viability. Nurs. Stand. 2013, 27, 62, 64, 66–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.X.; Xu, Y. Enhancing competency of clinical research nurses: A comprehensive training and evaluation framework. World J. Clin. Cases 2024, 12, 1378–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orriss-Dib, L. The research nurse’s role in managing patient expectation in clinical trials. Nurs. Times 2022, 118, 40–43. [Google Scholar]

- Brioni, E. L’Infermiere di Ricerca: Un point of view. L’Infermiere 2019, 1, 17–20. [Google Scholar]

- Rickard, C.M.; Roberts, B.L. Commentary on Spilsbury K, Petherick E, Cullum N, Nelson A, Nixon J & Mason S (2008) The role and potential contribution of clinical research nurses to clinical trials. J. Clin. Nurs. 2008, 17, 549–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyland, D.; Molone, M.C. Spotlight on clinical research nursing. World Ir. Nurs. Midwifery 2016, 24, 52–53. [Google Scholar]

- Liptrott, S.; Orlando, L.; Clerici, M.; Cocquio, A.; Martinelli, G. A competency based educational programme for research nurses: An Italian experience. Ecancer 2009, 3, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Huband, K.; Dobra, R.; Lewis, A.; Simpson, A. Perceptions of the role of the respiratory Clinical Research Nurse. Eur. Respir. J. 2018, 52, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguiar, D.F.; Camacho, K.G. The daily activity of the nurse in clinical research: An experience report. Revista da Escola de Enfermagem da USP 2010, 44, 526–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barthow, C.; Jones, B.; Macdonald, L.; Vernall, S.; Gallagher, P.; McKinlay, E. Researching in the community: The value and contribution of nurses to community based or primary health care research. Prim. Health Care Res. Dev. 2015, 16, 224–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, L.; Kulkarni, D. Perspectives of Oncology Nursing and Investigational Pharmacy in Oncology Research. Semin. Oncol. Nurs. 2020, 36, 151004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boulton, M.G.; Hopewell, N. The workforce delivering translational and applied health research: Across sectional survey of their characteristics, studies and responsibilities. Collegian 2017, 24, 469–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnett, C.; Bullock, L.; Collins, C.A.; Hauser, L. Evaluation of a Clinical Cancer Trial Research Training Workshop: Helping Nurses Build Capacity in Southwest Virginia. Public Health Nurs. 2016, 33, 565–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisk, B.; Beier, J. Study nurses in Germany—A survey of job-related activities in clinical trials as a basis for a job description and for training curricula. Pflege 2007, 20, 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabó, A.; Kurucz-Asztalos, N.; Demeter, Z.; Pikó, B.; Dank, M. A vizsgálati nővér („Study Nurse”) szerepe a klinikai gyógyszervizsgálatokban. Nővér 2021, 34, 34–39. [Google Scholar]

- Ness, E.A.; Royce, C. Clinical Trials and the Role of the Oncology Clinical Trials Nurse. Nurs. Clin. N. Am. 2017, 52, 133–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purdom, M.A.; Petersen, S.; Haas, B.K. Results of an Oncology Clinical Trial Nurse Role Delineation Study. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 2017, 44, 589–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinberg, H. Oncology Nurse Coordinators in Clinical Trials—Shaking up the Melanoma Team. Asia-Pac. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2020, 7, 250–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, D.C.; Gaudaur, H.; Marchant, M.; Viera, L.; McCubbin, A.; Verble, W.; Mendell, A.; Gilliam, C. Enhancing the clinical research workforce: A collaborative approach with human resources. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1295155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, C.T.; Griffith, C.A.; Fisher, C.A.; Grinke, K.A.; Keller, R.; Lee, H.; Purdom, M.; Turba, E. Nurses in clinical trials: Perceptions of impact on the research enterprise. J. Res. Nurs. 2022, 27, 50–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zucchelli, F.; Rumsey, N.; Humphries, K.; Bennett, R.; Davies, A.; Sandy, J.; Stock, N.M. Recruiting to cohort studies in specialist healthcare services: Lessons learned from clinical research nurses in UK cleft services. J. Clin. Nurs. 2018, 27, e787–e797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyte, D.; Ives, J.; Draper, H.; Keeley, T.; Calvert, M. Inconsistencies in Quality of Life Data Collection in Clinical Trials: A Potential Source of Bias? Interviews with Research Nurses and Trialists. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e76625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oncology nurses are playing key roles in clinical trials. Oncol. News Int. 2000, 9, 36–37. Available online: https://www.cancernetwork.com/view/oncology-nurses-are-playing-key-roles-clinical-trials (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Practice nurses play key role in unique clinical trial. Pract. Nurse 2014, 44, 10.

- Association, A.N. Specialty Practice of Clinical Research Nursing Recognized. Okla. Nurse 2016, 61, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Brearley, S. The ever-changing role of the diabetes specialist research nurse. J. Diabetes Nurs. 2014, 18, 37. [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy, J.; Macfarlane, D.K. The role of the nurse in clinical cancer-research. Cancer Nurs. 1991, 14, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catley, C. Clinical research nursing: A possible career pathway for renal nurses. J. Kidney Care 2016, 1, 92–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chester, P.; Kennedy, E.D.; Hynd, S.; Matthews, D.R. Clinical research networks in diabetes: The evolving role of the research nurse. Eur. Diabetes Nurs. 2007, 4, 10–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driver, R.L. How Did You Get That Job? Exploring the Role of the Perinatal Clinical Research Nurse. Jognn-J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. 2013, 42, S55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fish, L.C. Special focus. The role of the clinical research nurse. Mass. Nurse 1997, 67, 8–12. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs, C.L.; Lowton, K. The role of the clinical research nurse. Nurs. Stand. 2012, 26, 37–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grady, C. Viewpoint. Clinical research: The power of the nurse. AJN Am. J. Nurs. 2001, 101, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, L. Explaining the role of the nurse in clinical trials. Nurs. Stand. 2011, 25, 35–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herzog-LeBoeuf, C.; Willenberg, K.M. The History of Clinical Trials Research: Implications for Oncology Nurses. Semin. Oncol. Nurs. 2020, 36, 150997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodges, L.C.; Patterson, R.; Rapp, C.G. Clinical trials: The role of the neuroscience nurse. J. Neurosci. Nurs. 1990, 22, 195–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holaday, B.; Mills, D.M. Clinical research and the development of new drugs: Issues for nurses. Dimens. Crit. Care Nurs. 2004, 23, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackley, A.; Bollinger, M.; Lynch, S. Clinical Research Nursing. Nurs. Womens Health 2012, 16, 325–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCabe, M.; Lawrence, C.A.C. Viewpoint. The clinical research nurse. AJN Am. J. Nurs. 2007, 107, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDermott, S.; Hathaway, K.; Saunders, C. Developing good practice for clinical research nurses. Nurs. Stand. 2014, 28, 40–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moro-Tejedor, M.N.; García-Pozo, A. Role of the nurse in research. Rev. Esp. Salud Publica 2023, e1–e5. [Google Scholar]

- Perry, N. The role of clinical research nurse. HIV Nurs. 2007, 7, 17–18. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, K.; Gelder, S.; Wild, H. Clinical research nurse interns: The future research workforce. Nurse Res. 2016, 24, 6–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kampelman, J.A. Lived experiences of clinical research nurses: Competence and expectations, Dissertation Abstracts International Section A: Humanities and Social Sciences. Ph.D. Thesis, Saint Louis University, Saint Louis, MO, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez, A.G.; Castillo, G.; Argota, I.B.; Sanchis, M.; Sanz, M.; Suarez, I.; Ballabrera, F.S.; Montana, F.J.R.; Gonzalez, N.S.; Valdivìa, A.A.; et al. Role of translational oncology research nurse (TORN) in improving patients (pts) adherence to microbiome research projects. Ann. Oncol. 2023, 34, S1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCabe, M.; Behrens, L.; Browning, S.; Vessey, J.; Williams, M.J. CE: Original Research: The Clinical Research Nurse: Exploring Self-Perceptions About the Value of the Role. Am. J. Nurs. 2019, 119, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legor, K.A.; Hayman, L.L.; Foust, J.B.; Blazey, M.L. Clinical research nurses’ perceptions of the unique needs of people of color for successful recruitment to cancer clinical trials. Contemp. Clin. Trials 2023, 128, 107161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamer, S. The nurse’s changing role in clinical research. Nurs. Times 2015, 111, 12–14. [Google Scholar]

- Purdom, M.A. Validating a Taxonomy of Nursing Practice for Oncology Clinical Trial Nurses. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Texas at Tyler, Tyler, TX, USA, 2016; pp. 1–108. [Google Scholar]

- Mackle, D.; Nelson, K. Research nurses in New Zealand intensive care units: A qualitative descriptive study. Aust. Crit. Care 2019, 32, 148–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, P.; Wu, L.; Liu, Y. A survey on work status and competencies of Clinical Research Nurses in China. J. Res. Nurs. 2022, 27, 82–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, C.Y.; Huang, G.S.; Dai, Y.T.; Pai, Y.Y.; Hu, W.Y. An Investigation of the Role Responsibilities of Clinical Research Nurses in Conducting Clinical Trials. Hu Li Za Zhi 2015, 62, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, H.J.; Yu, S. The role of clinical trial nurses: Transitioning from clinicians to clinical research coordinators. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2022, 28, e12943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rickard, C.M.; Williams, G.; Ray-Barruel, G.; Armit, L.; Perry, C.J.; Luke, H.; Duffy, P.; Wallis, M. Towards improved organisational support for nurses working in research roles in the clinical setting: A mixed method investigation. Collegian 2011, 18, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, K.; White, K.; Johnson, C.; Roydhouse, J.K. Knowledge and skills of cancer clinical trials nurses in Australia. J. Adv. Nurs. 2012, 68, 1111–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkes, L.; Jackson, D.; Miranda, C.; Watson, R. The role of clinical trial nurses: An Australian perspective. Collegian 2012, 19, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinkler, L.; Robinson, L. Clinical research nursing and factors influencing success: A qualitative study describing the interplay between individual and organisational leadership influences and their impact on the delivery of clinical research in healthcare. J. Res. Nurs. 2020, 25, 361–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinkler, L.; Smith, V.; Yiannakou, Y.; Robinson, L. Professional identity and the Clinical Research Nurse: A qualitative study exploring issues having an impact on participant recruitment in research. J. Adv. Nurs. 2018, 74, 318–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legor, K.A.; Hayman, L.L.; Foust, J.B.; Blazey, M.L. The role of clinical research nurses in minority recruitment to cancer clinical trials. Contemp. Clin. Trials 2021, 110, 106590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adan, C. Clinical nurses’ understanding of the role of the clinical research nurse in the renal unit. Br. J. Nurs. 2023, 32, 183–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrigo, C.; Gall, H.; Delogne, A.; Molin, C. The involvement of nurses in clinical trials: Results of the EORTC Oncology Nurses Study Group survey. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer. Cancer Nurs. 1994, 17, 429–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lönn, B.B.; Olofsson, N.; Jong, M. Translation and validation of the Clinical Trial Nursing Questionnaire in Swedish-A first step to clarify the clinical research nurse role in Sweden. J. Clin. Nurs. 2019, 28, 2696–2705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lönn, B.B.; Hajdarevic, S.; Olofsson, N.; Hörnsten, Å.; Styrke, J. Clarifying the role of clinical research nurses working in Sweden, using the Clinical Trial Nursing Questionnaire—Swedish version. Nurs. Open 2022, 9, 2434–2443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cantini, F.; Ells, C. The role of the clinical trial nurse in the informed consent process. Can. J. Nurs. Res. 2007, 39, 126–144. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Catania, G.; Poirè, I.; Bernardi, M.; Bono, L.; Cardinale, F.; Dozin, B. The role of the clinical trial nurse in Italy. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2012, 16, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisher, C.A.; Griffith, C.A.; Lee, H.; Smith, H.A.; Jones, C.T.; Grinke, K.A.; Keller, R.; Cusack, G.; Browning, S.; Hill, G. Extending the description of the clinical research nursing workforce. J. Res. Nurs. 2022, 27, 102–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagel, K.; Gender, J.; Bonner, A. Delineating the role of a cohort of clinical research nurses in a pediatric cooperative clinical trials group. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 2010, 37, E180–E185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Shan, W.C.; Liu, J.M.; Zhang, Q.Q.; Ye, Y.; Huang, S.T.; Zhong, K. Construction of clinical research nurse training program based on position competence. World J. Clin. Cases 2023, 11, 7363–7371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, I.; Kong, H.S.; Kim, W.O. Clinical research nurses: Roles and qualifications in South Korea. Drug Inf. J. 2007, 41, 251–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulli, K.; Anderson, N.; Jones, E.S.; Brand, S. The role of the clinical research nurse in kidney settings. J. Kidney Care 2024, 9, 90–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pye, C.; Tinkler, L.; Metwally, M. Clinical research nurse and midwife as an integral member of the Trial Management Group (TMG): Much more than a resource to manage and recruit patients. BMJ Lead 2023, 7, 152–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xanthos, G.J.; Carp, D.; Geromanos, K.L. Recognizing nurses’ contributions to the clinical research process. JANAC J. Assoc. Nurses AIDS Care 1998, 9, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, K.; White, K.; Roydhouse, J.K. Advancing the educational and career pathway for clinical trials nurses. J. Contin. Educ. Nurs. 2013, 44, 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caselgrandi, A.; Guaraldi, G.; Cottafavi, K.; Artioli, G.; Ferri, P. Clinical Research Nurse involvement to foster a community based transcultural research in RODAM European study. Acta Biomed. 2016, 87 (Suppl. S2), 80–87. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jones, C.T.; Hastings, C.; Wilson, L.L. Research nurse manager perceptions about research activities performed by non-nurse clinical research coordinators. Nurs. Outlook 2015, 63, 474–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paglione, M.L. A day in the life of a clinical research nurse: By sharing their work diaries, three cancer clinical research nurses offer an insight into the challenges and rewards of the role. Cancer Nurs. Pract. 2019, 18, 18–20. [Google Scholar]

- Badalucco, S.; Reed, K.K. Supporting Quality and Patient Safety in Cancer Clinical Trials. Clin. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2011, 15, 263–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cousins, R. How clinical research nursing is shaping the future of urology trials. Br. J. Nurs. 2022, 31, 1136–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croudass, A. Research notes. A pilot role for nurses is helping to increase knowledge of cancer clinical trials. Nurs. Stand. 2003, 17, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cubells, M.; Rodriguez, A.; Sole, L.; Nascimento, A. The strategic role of the research nurse: No research nurse, no trial. Neuromuscul. Disord. 2019, 19, S112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardicre, J. Developing research nurses: A structured taxonomic model. Br. J. Nurs. 2013, 22, 416–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, J.; Liu, Y.; Gan, B.; Liu, Y.; Liu, X.; Qiao, J.; Zhao, Q.; Chang, T.; Wang, J.; Xing, J. Expert consensus on clinical research nurse management in China. Asia-Pac. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2023, 10, 100254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imran, A.; Mpofu, S.; Weldon, S.M. Clinical research nurses, perspectives on recruitment challenges and lessons learnt from a large multi-site observational study. J. Res. Nurs. 2022, 27, 579–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biswell, R.E.; Clark, M.; Tinelli, M.; Manthorpe, G.; Neale, J.; Whiteford, M.; Cornes, M. Beyond clinical trials: Extending the role of the clinical research nurse into social care and homeless research. J. Clin. Nurs. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lönn, B.B.; Hornsten, Å.; Styrke, J.; Hajdarevic, S. Clinical research nurses perceive their role as being like the hub of a wheel without real power: Empirical qualitative research. Nurs. Open 2024, 11, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forbes, S.G.; Phillips, C.A. Ethical Challenges Encountered by Clinical Trials Nurses: A Grounded Theory Study. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 2020, 47, 428–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godskesen, T.; Björk, J.; Juth, N. Challenges regarding informed consent in recruitment to clinical research: A qualitative study of clinical research nurses’ experiences. Trials 2023, 24, 801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larkin, M.E.; Beardslee, B.; Cagliero, E.; Griffith, C.A.; Milaszewski, K.; Mugford, M.T.; Myerson, J.M.; Ni, W.; Perry, D.J.; Winkler, S.; et al. Ethical challenges experienced by clinical research nurses: A qualitative study. Nurs. Ethics 2019, 26, 172–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, M.; Mamo, L. The nurse clinical trial coordinator: Benefits and drawbacks of the role. Res. Theory Nurs. Pract. 2002, 16, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spilsbury, K.; Petherick, E.; Cullum, N.; Nelson, A.; Nixon, J.; Mason, S. The role and potential contribution of clinical research nurses to clinical trials. J. Clin. Nurs. 2008, 17, 549–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godskesen, T.E.; Petri, S.; Eriksson, S.; Halkoaho, A.; Mangset, M.; Pirinen, M.; Nielsen, Z.E. When Nursing Care and Clinical Trials Coincide: A Qualitative Study of the Views of Nordic Oncology and Hematology Nurses on Ethical Work Challenges. J. Empir. Res. Hum. Res. Ethics 2018, 13, 475–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercieca-Bebber, R.; Calvert, M.; Kyte, D.; Stockler, M.; King, M.T. The administration of patient-reported outcome questionnaires in cancer trials: Interviews with trial coordinators regarding their roles, experiences, challenges and training. Contemp. Clin. Trials Commun. 2018, 9, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawton, J.; Jenkins, N.; Darbyshire, J.L.; Holman, R.R.; Farmer, A.J.; Hallowell, N. Challenges of maintaining research protocol fidelity in a clinical care setting: A qualitative study of the experiences and views of patients and staff participating in a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2011, 12, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueser, T.; Lawan, M. Trials and beyond: Role of the cardiovascular research nurse. Br. J. Card. Nurs. 2017, 12, 168–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramley, K.; Rees, J. The role of a clinical research dental nurse. Dent. Nurs. 2020, 16, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulson, C.; Grange, A. Developing clinical research nurses. Nurs. Times 2012, 108, 23–25. [Google Scholar]

- Hagan, T.; Francis, R.; Campbell, E. The role of the clinical research nurse: A Sir Charles Gardiner Hospital nuclear medicine department and WA PET service perspective. Intern. Med. J. 2013, 43, 28–29. [Google Scholar]

- Herena, P.S.; Paguio, G.; Pulone, B. Clinical Research Nurse Education: Using Scope and Standards of Practice to Improve Care, Clin. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2018, 22, 450–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hazelton, J. The role of the nurse in phase I clinical trials, Journal of Pediatric. Oncol. Nurs. 1991, 8, 43–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, J. Research and development. Clinical trials, palliative care and the research nurse. Int. J. Palliat. Nurs. 1997, 3, 192–196. [Google Scholar]

- Lawton, J.; Jenkins, N.; Darbyshire, J.; Farmer, A.; Holman, R.; Hallowell, N. Understanding the outcomes of multi-centre clinical trials: A qualitative study of health professional experiences and views. Soc. Sci. Med. 2012, 74, 574–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozzetti, M.; Soncini, S.; Bassi, M.C.; Guberti, M. Assessment of Nursing Workload and Complexity Associated with Oncology Clinical Trials: A Scoping Review. Semin. Oncol. Nurs. 2024, 40, 151711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napolitano, D.; Cascio, A.L.; Bozzetti, M.; Guberti, M. Implementing research, improving practice: Synergizing the clinical research nurse and the nurse researcher. Minerva Gastroenterol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedetti, F. Placebo and the new physiology of the doctor-patient relationship. Physiol. Rev. 2013, 93, 1207–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Research Questions (RQ) | |

|---|---|

| RQ1 | What is the scope of practice for CRNs? |

| RQ2 | What are the core competences of CRNs? |

| RQ3 | What obstacles are linked to the position of CRNs? |

| RQ4 | What is the current employment status of CRNs worldwide? |

| RQ5 | What geographical contexts have examined the role of CRNs? |

| RQ6 | What clinical and organizational settings have contributed to developing and implementing the CRN role? |

| RQ7 | What outcomes have been used to evaluate the impact of CRNs? |

| RQ8 | What emerging themes or subtopics have been identified through data mining techniques? |

| RQ9 | Is there a temporal pattern in the thematic focus of the literature, and are there emerging themes tied to specific publication periods? |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bozzetti, M.; Guberti, M.; Lo Cascio, A.; Privitera, D.; Genna, C.; Rodelli, S.; Turchini, L.; Amatucci, V.; Giordano, L.N.; Mora, V.; et al. Uncovering the Professional Landscape of Clinical Research Nursing: A Scoping Review with Data Mining Approach. Nurs. Rep. 2025, 15, 266. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15080266

Bozzetti M, Guberti M, Lo Cascio A, Privitera D, Genna C, Rodelli S, Turchini L, Amatucci V, Giordano LN, Mora V, et al. Uncovering the Professional Landscape of Clinical Research Nursing: A Scoping Review with Data Mining Approach. Nursing Reports. 2025; 15(8):266. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15080266

Chicago/Turabian StyleBozzetti, Mattia, Monica Guberti, Alessio Lo Cascio, Daniele Privitera, Catia Genna, Silvia Rodelli, Laura Turchini, Valeria Amatucci, Luciana Nicola Giordano, Vincenzina Mora, and et al. 2025. "Uncovering the Professional Landscape of Clinical Research Nursing: A Scoping Review with Data Mining Approach" Nursing Reports 15, no. 8: 266. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15080266

APA StyleBozzetti, M., Guberti, M., Lo Cascio, A., Privitera, D., Genna, C., Rodelli, S., Turchini, L., Amatucci, V., Giordano, L. N., Mora, V., Napolitano, D., & Caruso, R. (2025). Uncovering the Professional Landscape of Clinical Research Nursing: A Scoping Review with Data Mining Approach. Nursing Reports, 15(8), 266. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15080266