Nurse-Led Bereavement Support During the Time of Hospital Visiting Restrictions Imposed by the COVID-19 Pandemic—A Qualitative Study of Family Members’ Experiences

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Aim of the Study

2.2. Study Design

2.3. Context

2.4. Bereavement Support Service

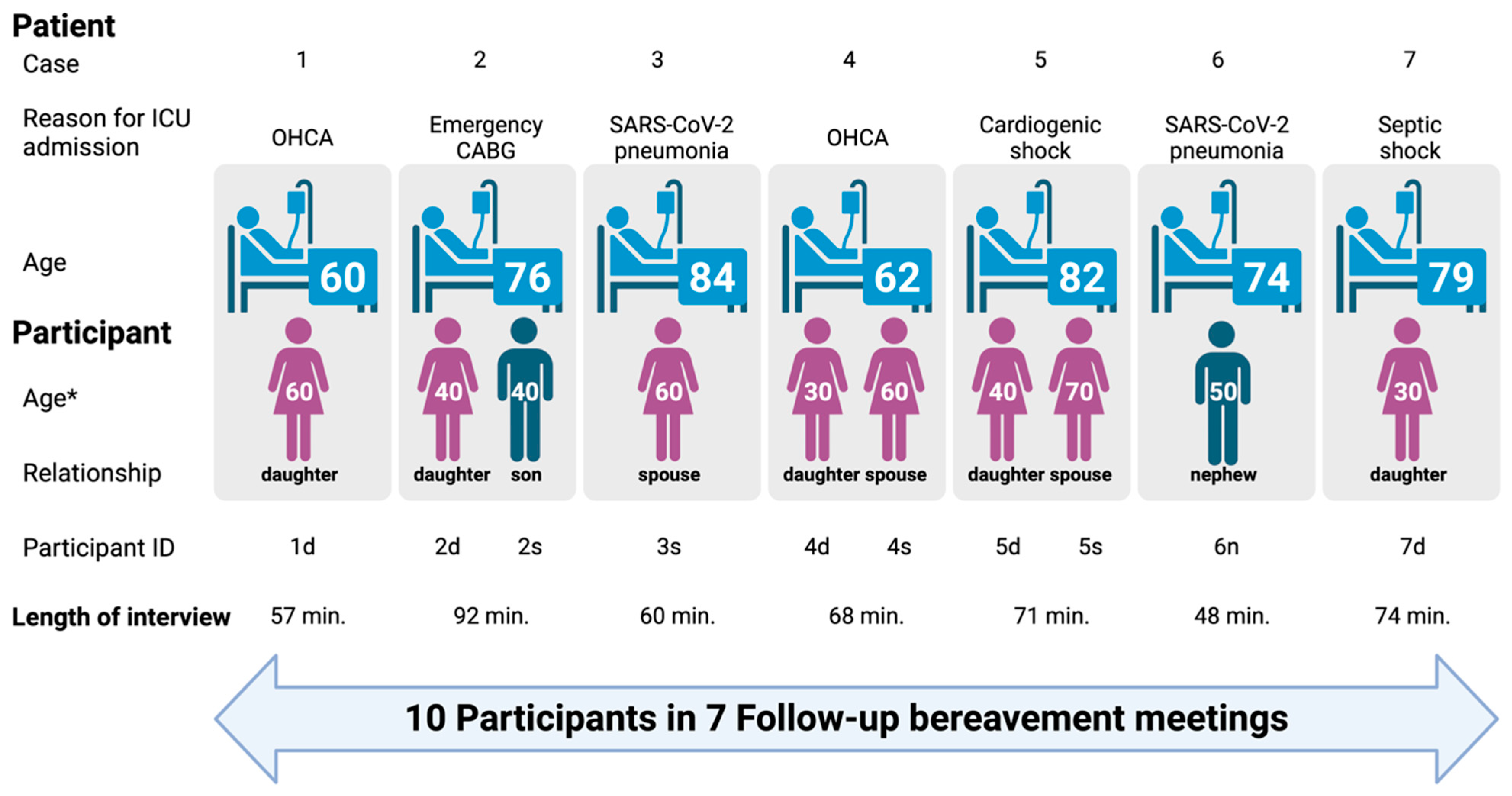

2.5. Sample

2.6. Data Collection

2.7. Data Analysis

2.8. Ethical Considerations

2.9. Accuracy and Trustworthiness

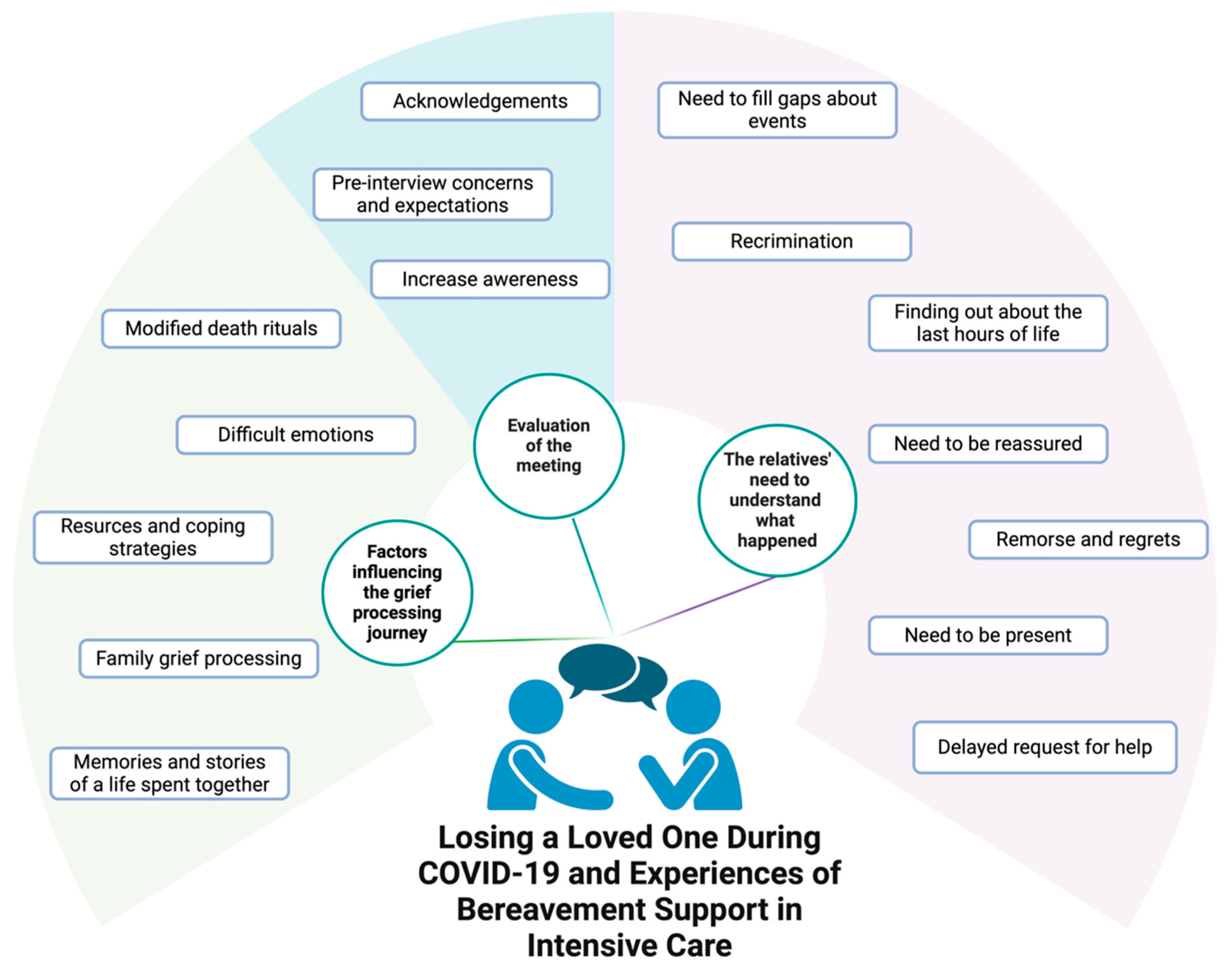

3. Findings

3.1. Theme 1: The Relatives’ Need to Understand What Happened

3.2. Theme 2: Factors Influencing the Grief Processing Journey

3.3. Theme 3: Evaluation of the Meeting

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Public Involvement Statement

Guidelines and Standards Statement

Use of Artificial Intelligence

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CABG | Coronary Artery Bypass Graft |

| COREQ | Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research |

| COVID-19 | COronaVIrus Disease 19 |

| ICU | Intensive Care Unit |

| OHCA | Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest |

| PTSD | Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder |

| SARS-Cov-2 | Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome COronaVirus 2 |

Appendix A

- Interview guide

- During your loved one’s hospitalization were you able to stay in touch with him? How were you able to get the information and reassurance about his health condition?

- During phone calls or brief visits, were you able to get clear information from the doctors and nurses? Would you have wished for something different?

- How do you consider the quality of information you received from doctors and nurses during phone calls? Would you have liked which thing was different?

- When did you last see your relative? What do you remember about that moment?

- After the death were you able to have someone close to talk to and share what you were going through?

- After the death were you able to have someone close to share what you were going through? Did you feel the need for support such as: attending physician, psychologist, priest, relatives? What were the predominant feelings?

- How did you feel when the condolence letter from the hospital reached you? And when you were contacted by phone?

- Today, coming to this meeting, what feelings and sensations did you have? Did you have clear expectations?

- During the meeting were you able to ask the questions you set out to ask? Did you receive clear answers? Did you feel listened to?

- Now that the meeting is over, how do you feel? Would you do it again?

- Do you find the meeting useful? Would you recommend it to other people who come to your situation?

References

- Yardley, S.; Rolph, M. Death and dying during the pandemic. BMJ 2020, 369, m1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallace, C.L.; Wladkowski, S.P.; Gibson, A.; White, P. Grief During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Considerations for Palliative Care Providers. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2020, 60, e70–e76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laranjeira, C.; Moura, D.; Marcon, S.; Jaques, A.; Salci, M.A.; Carreira, L.; Cuman, R.; Querido, A. Family bereavement care interventions during the COVID-19 pandemic: A scoping review protocol. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e057767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, D.; Boerner, K.; Moorman, S. Bereavement in the Time of Coronavirus: Unprecedented Challenges Demand Novel Interventions. J. Aging Soc. Policy 2020, 32, 425–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siddique, H.; Marsh, S. Coronavirus: Britons Saying Final Goodbyes to Dying Relatives by Videolink. The Guardian. 2020. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/mar/24/britons-saying-final-goodbyes-to-dying-relatives-by-videolink-covid-19 (accessed on 22 March 2023).

- Van Schaik, T.; Brouwer, M.A.; Knibbe, N.E.; Knibbe, H.J.J.; Teunissen, S.C.C.M. The Effect of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Grief Experiences of Bereaved Relatives: An Overview Review. Omega 2022, 91, 851–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kentish-Barnes, N.; Cohen-Solal, Z.; Morin, L.; Souppart, V.; Pochard, F.; Azoulay, E. Lived Experiences of Family Members of Patients With Severe COVID-19 Who Died in Intensive Care Units in France. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2113355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labram, A.H.; Johnston, B.; McGuire, M. An integrative literature review examining the key elements of bereavement follow-up interventions in critical care. Curr. Opin. Support. Palliat. Care 2023, 17, 193–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa, M.; Gallo, D.; Palermo, A.; Tiziano, C. Follow-up meeting post death, an unmet need: The right moment to start. Minerva Anestesiol. 2020, 86, 1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kentish-Barnes, N.; Chevret, S.; Valade, S.; Jaber, S.; Kerhuel, L.; Guisset, O.; Martin, M.; Mazaud, A.; Papazian, L.; Argaud, L.; et al. A three-step support strategy for relatives of patients dying in the intensive care unit: A cluster randomised trial. Lancet 2022, 399, 656–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downar, J.; Barua, R.; Sinuff, T. The desirability of an Intensive Care Unit (ICU) clinician-led bereavement screening and support program for family members of ICU Decedents (ICU Bereave). J. Crit. Care 2014, 29, 311.e9–311.e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kentish-Barnes, N.; Chevret, S.; Champigneulle, B.; Thirion, M.; Souppart, V.; Gilbert, M.; Lesieur, O.; Renault, A.; Garrouste-Orgeas, M.; Argaud, L.; et al. Effect of a condolence letter on grief symptoms among relatives of patients who died in the ICU: A randomized clinical trial. Intensive Care Med. 2017, 43, 473–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kock, M.; Berntsson, C.; Bengtsson, A. A follow-up meeting post death is appreciated by family members of deceased patients. Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand. 2014, 58, 891–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fridh, I.; Åkerman, E. Family-centred end-of-life care and bereavement services in Swedish intensive care units: A cross-sectional study. Nurs. Crit. Care 2019, 25, 291–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watland, S.; Solberg Nes, L.; Ekeberg, Ø.; Rostrup, M.; Hanson, E.; Eksted, M.; Stenderg, U.; Hagen, M.; Børøsund, E. The Caregivers Pathway Intervention can contribute to reduced post-intensive care syndrome among family caregivers of ICU survivors: A randomized controlled trial. Crit. Care Med. 2025, 53, e555–e566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menichetti Delor, J.P.; Borghi, L.; Cao di San Marco, E.; Fossati, I.; Vegni, E. Phone follow up to families of COVID-19 patients who died at the hospital: Families’ grief reactions and clinical psychologists’ roles. Int. J. Psychol. 2021, 56, 498–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, C.; Honey, J.R.; Lovick, R.; Zapiain Creamer, N.; Henry, C.; Langford, A.; Stobert, M.; Barclay, S. ‘A silent epidemic of grief’: A survey of bereavement care provision in the UK and Ireland during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e046872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillippi, J.; Lauderdale, J. A Guide to Field Notes for Qualitative Research: Context and Conversation. Qual. Health Res. 2018, 28, 381–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graneheim, U.H.; Lundman, B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ. Today 2004, 24, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, B.; Sim, J.; Kingstone, T.; Baker, S.; Waterfield, J.; Bartlam, B.; Burroughs, H.; Jinks, C. Saturation in qualitative research: Exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Qual. Quant. 2018, 52, 1893–1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, S.; Xiang, Z. Who suffered most after deaths due to COVID-19? Prevalence and correlates of prolonged grief disorder in COVID-19 related bereaved adults. Glob. Health 2021, 17, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeitziner, M.M.; Camenisch, S.A.; Jenni-Moser, B.; Schefold, J.C.; Zante, B. End-of-life care during the COVID-19 pandemic-What makes the difference? Nurs. Crit. Care 2021, 26, 212–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradi, S. Emotional supportive care for first-degree relatives of deceased people with COVID-19: An important but neglected issue. Evid. Based Nurs. 2022, 25, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, W.; Trapani, J. Spotlight on Bereavement Care. Nurs. Crit. Care 2018, 23, 169–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kentish-Barnes, N.; Chaize, M.; Seegers, V.; Legriel, S.; Cariou, A.; Jaber, S.; Lefrant, J.Y.; Floccard, B.; Renault, A.; Vinatier, I.; et al. Complicated grief after death of a relative in the intensive care unit. Eur. Respir. J. 2015, 45, 1341–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mailer, J.; Ward, K.; Aspinall, C. The impact of visiting restrictions in intensive care units for families during the COVID-19 pandemic: An integrative review. J. Adv. Nurs. 2023, 80, 1355–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bloomer, M.J.; Ranse, K. How the COVID-19 pandemic has reaffirmed the priorities for end-of-life care in critical care: Looking to the future. Intensive Crit. Care Nurs. 2022, 72, 103259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Martínez, E.; Mapango, E.A.; Martínez-Fernández, M.C.; Valle-Barrio, V. Family-centred care of patients admitted to the intensive care unit in times of COVID-19: A systematic review. Intensive Crit. Care Nurs. 2022, 70, 103223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloomer, M.J.; Walshe, C. Smiles behind the masks: A systematic review and narrative synthesis exploring how family members of seriously ill or dying patients are supported during infectious disease outbreaks. Palliat. Med. 2021, 35, 1452–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egerod, I.; Kaldan, G.; Coombs, M.; Mitchell, M. Family-centered bereavement practices in Danish intensive care units: A cross-sectional national survey. Intensive Crit. Care Nurs. 2018, 45, 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, M.; Coombs, M.; Wetzig, K. The provision of family-centred intensive care bereavement support in Australia and New Zealand: Results of a cross sectional explorative descriptive survey. Aust. Crit. Care 2017, 30, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berry, M.; Brink, E.; Metaxa, V. Time for change? A national audit on bereavement care in intensive care units. J. Intensive Care Soc. 2017, 18, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kesecioglu, J.; Rusinova, K.; Alampi, D.; Arabi, Y.M.; Benbenishty, J.; Benoit, D.; Boulanger, C.; Cecconi, M.; Cox, C.; van Dam, M.; et al. European Society of Intensive Care Medicine guidelines on end of life and palliative care in the intensive care unit. Intensive Care Med. 2024, 50, 1740–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Main Theme 1: The Relatives’ Need to Understand What Happened | ||

|---|---|---|

| Sub-Themes | # | Quotes (ID Participant) |

| Need to fill gaps about events | 1 | I just want to know what happened the day he got here. All I know was that one moment he was on the phone with his girlfriend and the next he was being intubated… (7d) |

| 2 | We knew about his heart condition, but he lived a long life. It’s hard to make sense of it, all these thoughts that come up afterwards are hard to process. (5d) | |

| 3 | The first question is about re-capping everything… not that it’s not clear, by now everything’s clear. At the beginning you had administered her antibiotics because it was written that whoever had performed the heart massage had transmitted something to her. Not sure about this, I think I’m still wrapping my head around this part. (1d) | |

| Recriminations | 4 | At home, my mother and I were wondering, because the matter is still somewhat… unclear. He had had a medical check-up done, after which no follow-up was done because of the COVID outbreak. And then he got admitted here as an urgent case… and it’s unclear if he should have maybe been admitted sooner… (5s) |

| 5 | The night he died, I must say I was really angry with the nurse who asked that I call later as apparently they were busy with some paperwork at the time. A few hours later, my brother called to tell me that dad had passed away. I’d like to talk about this. I’d like to make it understood that this is a delicate matter and to be more sensitive because… when a father dies… and until the very end I couldn’t be with him or see him… I mean, knowing my father is there, sick, and me being completely cut off. Is it too much to ask to know something about it? (2s) | |

| Finding out about the last hours of life | 6 | Ever since the ambulance took him away, we were unable to reach him… The following day at three o’clock they called, telling us that he’d died. I’d like to know if he was aware, if he said anything. Can it be possible that he didn’t utter even a single word? (5s) |

| 7 | I’m unsure whether he was aware of what happened or not. If he really never asked for me, if prior to surgery he had asked to see someone or have something, in the end I don’t know, I mean he must have been confused, scared… (2s) | |

| 8 | I need to know if he passed away peacefully, and I know it’s a hard question to answer, but you know, my children are asking me if their uncle liked the drawings that we sent him… (6n) | |

| Need to be reassured | 9 | Another question, because I wasn’t there unfortunately, that I’m being asked by her, and by my brother is: was he awake and aware? Was he sedated during his passing? (2d) |

| 10 | Yes, what you told me about him passing away peacefully, unaware, has helped me. This is something that eases my mind a little… it helps dealing with the thought that we weren’t there during the darkest moments. (5d) | |

| 11 | It’s really nice to hear what you’re telling me, it helps me knowing that he passed away peacefully. (4s) | |

| Remorse and regrets | 12 | Then there’s that thought that still lingers: maybe I could have, not seen him alive necessarily, but you know, be there for him. Being able to say that, even though he’d already made his decision, I could be close to him…. (2d) |

| 13 | I would have liked to see him just one more time. It was a wish of mine, one that I was denied. For my personal story it would have been an important moment. I was there in the funeral home, and it was there that I saw my father, alone, inside the coffin. I regret that he left this world alone, that he had none of us there with him. (2s) | |

| 14 | I asked myself this later, once I had realised, “why hadn’t I asked if it was possible for me to be there in the hospital”. Surely you would have told me it wasn’t, but it’s something that I now regret not having asked; it’s a burden I carry inside me, I feel the guilt. (5d) | |

| Need to be present | 15 | ... it shouldn’t have happened during this situation, this COVID situation; in the end, that night my mum called for an ambulance, and that was the last time we saw him. That is what is really, really hard to accept. (4d) |

| 16 | I wanted to see him, but they kept telling me: “We can’t let you in”. I told them that I needed to see him, talk to him. “No, it’s not possible,” they insisted. I only saw him again at the funeral. He is dead… (3s) | |

| 17 | ... I could have mustered up the courage to see him intubated, even while hooked up to a machine, for even a second. Even as he was dying. But I saw him in a coffin. I couldn’t do anything…. (2s) | |

| Delayed request for help | 18 | If it hadn’t been for COVID, he would have seen the medic in time. (4s) |

| 19 | It was because of the Coronavirus situation that I told her: “mum, if you’re not feeling well, we can go to the hospital.” And she answered: “No, no, that’s where the Coronavirus is… She was terrorised by this COVID business, and she would never have called. She decided all on her own, she could have called anyone, but she didn’t. (1d) | |

| Theme 2: Factors influencing the grief processing journey | ||

| Modified funeral rituals | 20 | When he died. Eh. They called me on my phone telling me that Mr. X had died, but that I couldn’t come to the hospital. During the funeral I saw him inside a bag, inside a coffin. Only five people from the family were allowed to be present. But why? So many people knew him and would have liked to be present, but we were powerless. (3s) |

| 21 | We were lucky enough to be able to arrange a small funeral, with about 10 people, out in the open. My father’s partner couldn’t come however, as she was out of Switzerland at that time. (7d) | |

| Difficult emotions | 22 | When you then lose your last parent, you’re overcome by the feeling of being an orphan. That’s what it feels like. Doesn’t matter if you’re not a child anymore. When you lose your original family. This is what hurts most and is so hard to accept… and what’s more my brother’s far away. (7d) |

| 23 | I don’t feel so well, I feel like crying now… because the day I lost him I refused to cry… he died here in the hospital. I still can’t bring myself to accept that he died. Today’s the first time I’ve allowed myself to cry. From the day he left I still hadn’t cried. (3s) | |

| 24 | ... I want to remember her alive, still warm. And then we saw her, at the funeral home, inside the coffin… I wasn’t sure if I wanted to look inside. I told myself: “Come on! It’s my own mother!” (crying)… it’s not something so obvious for everyone… damn it! I hadn’t cried in two weeks. (1d) | |

| Resources and coping strategies | 25 | Working has helped me. I spent a few days at home, but then started going in again. Working has allowed me to get out of my head. Once you’re at work, you leave other problems at the door. That has helped me, it’s been a useful resource. (5d) |

| 26 | It’s just the two of us now, and we support and encourage each other. (5s) | |

| 27 | My dad’s being extremely supportive, and my partner and my friends are also helping. I have two good friends from the volleyball team who have also lost their mother, they give good advice and have gotten to be quite close. (1d) | |

| 28 | I’ve also spoken about this to the priest. We talked about family relationships and marital relationships. He knew him well, and has been really helpful through all of this. (5s) | |

| Family grief processing | 29 | Still today his partner, despite the fact that it’s now been several months, has difficulties sleeping cause she sees him there. Lying on the floor. Compared to the first days, she now seems to be feeling slightly better. (2s) |

| 30 | Before going out, my younger son asked me why I still come here… that evening he cried all night long. The older one is more introverted, closed off, and I think he still hasn’t processed the whole thing, he needs time. We didn’t take them to their grandpa’s funeral. (2s) | |

| Memories and stories of a life spent together | 31 | He was my father’s cousin, so something like an uncle, but he really did a lot for us. He taught me many things, just like an uncle would, like tying my shoelaces when I was little. My children have always seen him as a grandfather of sorts. They never met their real grandpa. In the end, they did have a grandfather. (6n) |

| 32 | A few months ago, it was me and my brother in one room, while my son was in the other room with grandpa and they were chatting. It was a rare and pleasant situation as my father never used to speak much. The pleasant memories need to slowly replace the painful ones. (7d) | |

| 33 | He didn’t live with us, he left home when I was 6 years old. It could be that my relationship with him improved when I got married. (2d) | |

| 34 | ... we talked a bit about us, about our story. (2s) | |

| Theme 3: Evaluation of the meeting | ||

| Pre-interview concerns and expectations | 35 | When I got the letter, I immediately thought: “Wow what a nice service. It’s unusual to find hospitals offering something like it. How nice!” My mum’s partner, on the other hand, immediately dismissed it, saying that he wouldn’t come. He didn’t want to relive the whole experience. However, as soon as I got here, I said to myself: “Why did I to this, now everything’s going to come back to the surface”. (1d) |

| 36 | My daughter was against me coming here. I told her that I wanted to do this because I wanted to know, because in any case thoughts and questions always come to mind about this. I want to know how he died, if he called for us, if he felt distressed. That’s how it is, isn’t it? (5s) | |

| 37 | After you called, I said to myself: “Let’s do it”. My husband told me that it would only hurt me, going back to the hospital means reliving the whole thing, experiencing it again. I don’t agree, I need to put the pieces together. (5d) | |

| 38 | My brother didn’t want to come because he was afraid he’d get angry. (7d) | |

| Acknowledgements | 39 | I really appreciated this, thank you. I feel a bit better as I was finally able to talk about what I had bottled up inside. I’ve never cried until now. I couldn’t talk about it openly with my daughter because the whole thing makes her cry every time it comes up. (3s) |

| 40 | We now have no further questions, talking about this has brought us some relief. Well done. It’s a nice thing you’re doing, really. (5s) | |

| 41 | I think that what you’re doing here can be truly helpful, more than ever in this moment. People need this. (5d) | |

| Increased awareness | 42 | It’s been good for me as at least I know what really went on with my father. I wasn’t involved in the situation at the time, as I was informed mostly through what my brother told me. He would come to me and tell me: “Look, they decided this and that. and so on and so forth”. Thanks to you I now have had a genuine and direct testimony. (2s) |

| 43 | I can’t say I’m at peace, because it’s really going to take a lot of time as we were very close, but still talking about it to you and learning a few more facts has helped me. (5d) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Villa, M.; Palermo, A.; Montemarano, D.G.; Bottega, M.; Deelen, P.; Grassellini, P.R.; Bernasconi, S.; Cassina, T. Nurse-Led Bereavement Support During the Time of Hospital Visiting Restrictions Imposed by the COVID-19 Pandemic—A Qualitative Study of Family Members’ Experiences. Nurs. Rep. 2025, 15, 254. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15070254

Villa M, Palermo A, Montemarano DG, Bottega M, Deelen P, Grassellini PR, Bernasconi S, Cassina T. Nurse-Led Bereavement Support During the Time of Hospital Visiting Restrictions Imposed by the COVID-19 Pandemic—A Qualitative Study of Family Members’ Experiences. Nursing Reports. 2025; 15(7):254. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15070254

Chicago/Turabian StyleVilla, Michele, Annunziata Palermo, Dora Gallo Montemarano, Michela Bottega, Paula Deelen, Paola Rusca Grassellini, Stefano Bernasconi, and Tiziano Cassina. 2025. "Nurse-Led Bereavement Support During the Time of Hospital Visiting Restrictions Imposed by the COVID-19 Pandemic—A Qualitative Study of Family Members’ Experiences" Nursing Reports 15, no. 7: 254. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15070254

APA StyleVilla, M., Palermo, A., Montemarano, D. G., Bottega, M., Deelen, P., Grassellini, P. R., Bernasconi, S., & Cassina, T. (2025). Nurse-Led Bereavement Support During the Time of Hospital Visiting Restrictions Imposed by the COVID-19 Pandemic—A Qualitative Study of Family Members’ Experiences. Nursing Reports, 15(7), 254. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15070254