Exploring Applications of Artificial Intelligence in Critical Care Nursing: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

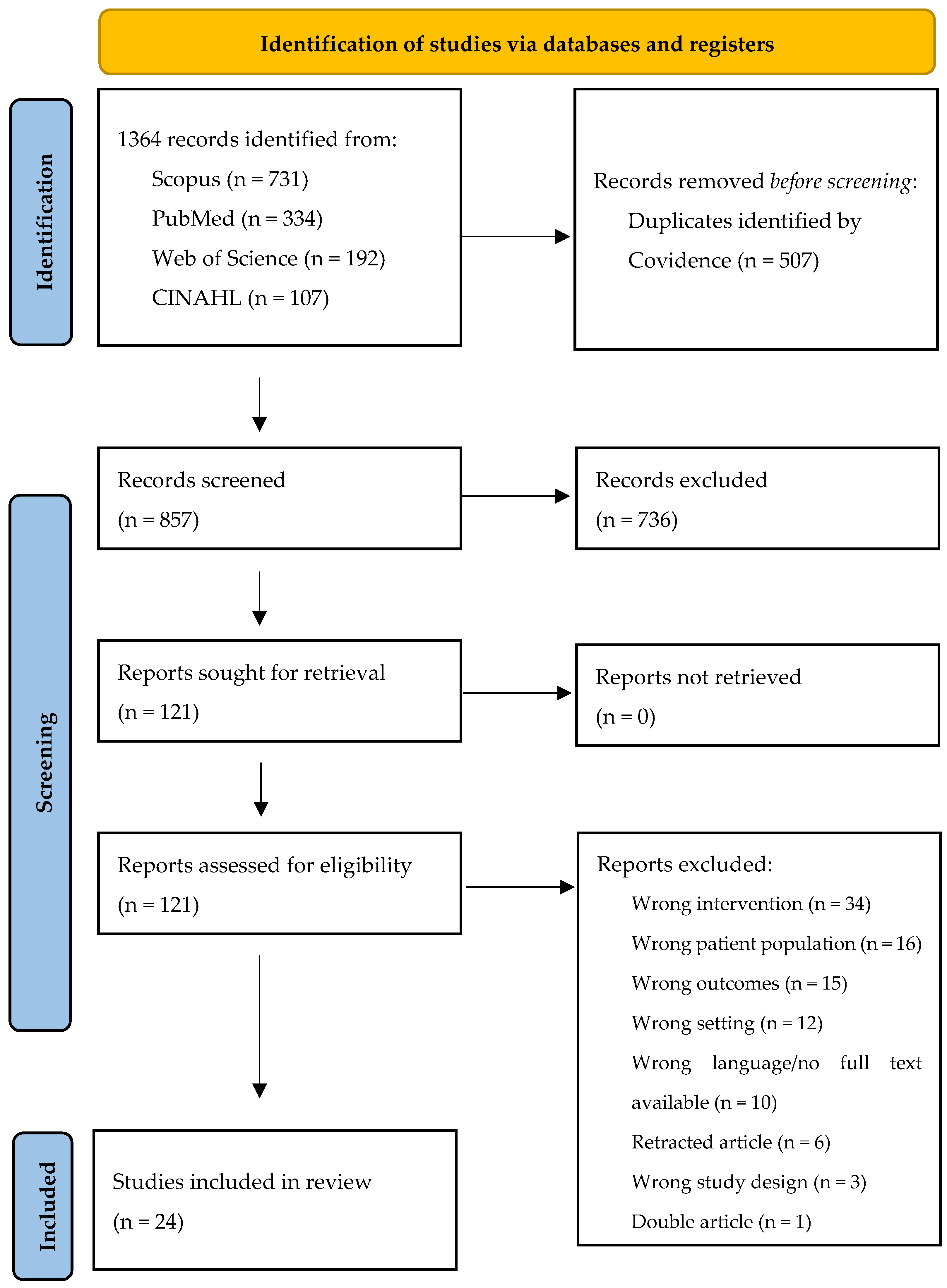

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Study Selection

2.4. Data Extraction

2.5. Studies’ Quality Assessment

2.6. Knowledge Synthesis

3. Results

3.1. General Characteristics

| Total Sample Size | Number of Studies |

|---|---|

| <100 | 2 |

| 100–1000 | 4 |

| 1000–10,000 | 6 |

| 10,000–100,000 | 6 |

| >100,000 | 5 |

3.2. Training Models’ Techniques

3.3. Type of Data Approach

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications for Nursing Practice

4.2. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Public Involvement Statement

Guidelines and Standards Statement

Use of Artificial Intelligence

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Samoili, S.; Lopez, C.M.; Gomez, G.E.; De, P.G.; Martinez-Plumed, F.; Delipetrev, B. AI WATCH. Defining Artificial Intelligence. Available online: https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/handle/JRC118163 (accessed on 14 May 2024).

- Gutierrez, G. Artificial Intelligence in the Intensive Care Unit. Crit. Care 2020, 24, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellini, V.; Valente, M.; Gaddi, A.V.; Pelosi, P.; Bignami, E. Artificial Intelligence and Telemedicine in Anesthesia: Potential and Problems. Minerva Anestesiol. 2022, 88, 729–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chee, M.L.; Ong, M.E.H.; Siddiqui, F.J.; Zhang, Z.; Lim, S.L.; Ho, A.F.W.; Liu, N. Artificial Intelligence Applications for COVID-19 in Intensive Care and Emergency Settings: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2021, 18, 4749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rafie, N.; Jentzer, J.C.; Noseworthy, P.A.; Kashou, A.H. Mortality Prediction in Cardiac Intensive Care Unit Patients: A Systematic Review of Existing and Artificial Intelligence Augmented Approaches. Front. Artif. Intell. 2022, 5, 876007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallifant, J.; Zhang, J.; del Pilar Arias Lopez, M.; Zhu, T.; Camporota, L.; Celi, L.A.; Formenti, F. Artificial Intelligence for Mechanical Ventilation: Systematic Review of Design, Reporting Standards, and Bias. Br. J. Anaesth. 2022, 128, 343–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrini, F.; Gendreau, S.; Morel, J.; Carteaux, G.; Thille, A.W.; Antonelli, M.; Mekontso Dessap, A. Prediction of Extubation Outcome in Critically Ill Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Crit. Care 2021, 25, 391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adebayo, O.; Bhuiyan, Z.A.; Ahmed, Z. Exploring the Effectiveness of Artificial Intelligence, Machine Learning and Deep Learning in Trauma Triage: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Digit. Health 2023, 9, 20552076231205736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alderden, J.; Pepper, G.A.; Wilson, A.; Whitney, J.D.; Richardson, S.; Butcher, R.; Jo, Y.; Cummins, M.R. Predicting Pressure Injury in Critical Care Patients: A Machine-Learning Model. Am. J. Crit. Care 2018, 27, 461–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, E.A.; El-Ashry, A.M. Leading with AI in critical care nursing: Challenges, opportunities, and the human factor. BMC Nurs. 2024, 23, 752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covidence—Better Systematic Review Management. Available online: https://www.covidence.org/ (accessed on 10 May 2024).

- Hong, Q.N.; Pluye, P.; Fabregues, S.; Bartlett, G.; Boardman, F.; Cargo, M.; Dagenais, P.; Gagnon, M.-P.; Griffiths, F.; Nicolau, B.; et al. Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT), Version 2018. Available online: http://mixedmethodsappraisaltoolpublic.pbworks.com/w/file/fetch/127916259/MMAT_2018_criteria-manual_2018-08-01_ENG.pdf (accessed on 14 May 2024).

- Abraham, J.; Bartek, B.; Meng, A.; Ryan King, C.; Xue, B.; Lu, C.; Avidan, M.S. Integrating Machine Learning Predictions for Perioperative Risk Management: Towards an Empirical Design of a Flexible-Standardized Risk Assessment Tool. J. Biomed. Inform. 2023, 137, 104270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyfroidt, G.; Güiza, F.; Cottem, D.; De Becker, W.; Van Loon, K.; Aerts, J.-M.; Berckmans, D.; Ramon, J.; Bruynooghe, M.; Van den Berghe, G. Computerized Prediction of Intensive Care Unit Discharge after Cardiac Surgery: Development and Validation of a Gaussian Processes Model. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2011, 11, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mutegeki, H.; Nahabwe, A.; Nakatumba-Nabende, J.; Marvin, G. Interpretable Machine Learning-Based Triage For Decision Support in Emergency Care. In Proceedings of the 2023 7th International Conference on Trends in Electronics and Informatics (ICOEI), Tirunelveli, India, 11–13 April 2023; pp. 983–990. [Google Scholar]

- Nazzal, L.; Arafeh, E.; Diab, H.; Nassar, M.; Shamayleh, A.; Awad, M. Utilization of Machine Learning in Patient Admission into Intensive Care Units. In Proceedings of the 2020 Advances in Science and Engineering Technology International Conferences (ASET), Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 4 February–9 April 2020; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- De Koning, E.; van der Haas, Y.; Saguna, S.; Stoop, E.; Bosch, J.; Beeres, S.; Schalij, M.; Boogers, M. AI Algorithm to Predict Acute Coronary Syndrome in Prehospital Cardiac Care: Retrospective Cohort Study. JMIR Cardio 2023, 7, e51375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaboli, A.; Brigo, F.; Sibilio, S.; Mian, M.; Turcato, G. Human Intelligence versus Chat-GPT: Who Performs Better in Correctly Classifying Patients in Triage? Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2024, 79, 44–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, S.; Lee, E.W.; Zhang, W.; Simpson, R.L.; Hertzberg, V.S.; Ho, J.C. Evaluating Natural Language Processing Packages for Predicting Hospital-Acquired Pressure Injuries From Clinical Notes. CIN Comput. Inform. Nurs. 2024, 42, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horng, S.; Sontag, D.A.; Halpern, Y.; Jernite, Y.; Shapiro, N.I.; Nathanson, L.A. Creating an Automated Trigger for Sepsis Clinical Decision Support at Emergency Department Triage Using Machine Learning. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0174708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, O.; Wolf, L.; Brecher, D.; Lewis, E.; Masek, K.; Montgomery, K.; Andrieiev, Y.; McLaughlin, M.; Liu, S.; Dunne, R.; et al. Improving ED Emergency Severity Index Acuity Assignment Using Machine Learning and Clinical Natural Language Processing. J. Emerg. Nurs. 2021, 47, 265–278.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramer, E.M.; Seneviratne, M.G.; Sharifi, H.; Ozturk, A.; Hernandez-Boussard, T. Predicting the Incidence of Pressure Ulcers in the Intensive Care Unit Using Machine Learning. EGEMs Gener. Evid. Methods Improv. Patient Outcomes 2019, 7, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenbaum, N.R.; Jernite, Y.; Halpern, Y.; Calder, S.; Nathanson, L.A.; Sontag, D.A.; Horng, S. Improving Documentation of Presenting Problems in the Emergency Department Using a Domain-Specific Ontology and Machine Learning-Driven User Interfaces. Int. J. Med. Inf. 2019, 132, 103981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.Y.; Jeong, G.Y.; Jeong, O.S.; Chang, D.K.; Cha, W.C. Machine Learning and Initial Nursing Assessment-Based Triage System for Emergency Department. Healthc. Inform. Res. 2020, 26, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsumoto, S.; Matsuoka, K.; Yokoyama, S. Risk Mining in Hospital Information Systems. In Proceedings of the Sixth IEEE International Conference on Data Mining—Workshops (ICDMW’06), Hong Kong, China, 18–22 December 2006; pp. 699–704. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.Y.; Park, H.-A.; Chung, E. Use of Electronic Critical Care Flow Sheet Data to Predict Unplanned Extubation in ICUs. Int. J. Med. Inf. 2018, 117, 6–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.-L.; Kuo, Y.-T.; Kuo, L.-C.; Liang, H.-P.; Cheng, Y.-W.; Yeh, Y.-C.; Tsai, M.-T.; Chan, W.-S.; Chiu, C.-T.; Chao, A.; et al. Early Prediction of Delirium upon Intensive Care Unit Admission: Model Development, Validation, and Deployment. J. Clin. Anesth. 2023, 88, 111121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, A.J.; Angus, D.C.; Cooper, G.F.; Mowery, D.L.; Seaman, J.B.; Potter, K.M.; Bukowski, L.A.; Al-Khafaji, A.; Gunn, S.R.; Kahn, J.M. A Voice-Based Digital Assistant for Intelligent Prompting of Evidence-Based Practices during ICU Rounds. J. Biomed. Inform. 2023, 146, 104483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, D.; Chang, D.; Pourhomayoun, M. Risk Prediction of Critical Vital Signs for ICU Patients Using Recurrent Neural Network. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Computational Science and Computational Intelligence (CSCI), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 5–7 December 2019; pp. 1003–1006. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharyya, A.; Sheikhalishahi, S.; Torbic, H.; Yeung, W.; Wang, T.; Birst, J.; Duggal, A.; Celi, L.A.; Osmani, V. Delirium Prediction in the ICU: Designing a Screening Tool for Preventive Interventions. JAMIA Open 2022, 5, ooac048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Chen, D.; Deng, X.; Pan, X.; Chen, Y.; Zhuang, X.; Sun, C. Development and Validation of a Machine Learning Algorithm–Based Risk Prediction Model of Pressure Injury in the Intensive Care Unit. Int. Wound J. 2022, 19, 1637–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladios-Martin, M.; Fernández-de-Maya, J.; Ballesta-López, F.-J.; Belso-Garzas, A.; Mas-Asencio, M.; Cabañero-Martínez, M.J. Predictive Modeling of Pressure Injury Risk in Patients Admitted to an Intensive Care Unit. Am. J. Crit. Care 2020, 29, e70–e80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toledo, L.V.; Bhering, L.L.; Ercole, F.F. Artificial Intelligence to Predict Bed Bath Time in Intensive Care Units. Rev. Bras. Enferm. 2024, 77, e20230201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, L.; Jin, L. Predicting ICU Pressure Injuries with Historical Data: A Multivariate Time Series Approach. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Knowledge Graph (ICKG), Shanghai, China, 1–2 December 2023; pp. 100–107. [Google Scholar]

- Brandao-de-Resende, C.; Melo, M.; Lee, E.; Jindal, A.; Neo, Y.N.; Sanghi, P.; Freitas, J.R.; Castro, P.V.I.P.; Rosa, V.O.M.; Valentim, G.F.S.; et al. A Machine Learning System to Optimise Triage in an Adult Ophthalmic Emergency Department: A Model Development and Validation Study. eClinicalMedicine 2023, 66, 102331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, A.; Min, I.K.; Hong, S.; Chung, H.S.; Lee, H.S.; Kim, J.H. Effect of Applying a Real-Time Medical Record Input Assistance System With Voice Artificial Intelligence on Triage Task Performance in the Emergency Department: Prospective Interventional Study. JMIR Med. Inform. 2022, 10, e39892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, M.; Johnson, K. Applied Predictive Modeling, 1st ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013; ISBN 978-1-4614-6848-6. [Google Scholar]

| Author(s) and Year | Country | Study Design | Health Outcomes | Critical Care Setting |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abraham et al., 2023 [14] | USA | Qualitative study | Postoperative complications (delirium, AKI, DVT, pneumonia, pulmonary embolism) | ICU, OR (perioperative setting) |

| Meyfroidt et al., 2011 [15] | Belgium | Observational study | Intensive care unit discharge: second day discharge prediction and day of discharge. | ICU |

| Mutegeki et al., 2023 [16] | USA | Observational study | Triage level: emergency severity index | ED |

| Nazzal et al., 2020 [17] | USA | Observational study | Intensive care unit admission | ICU |

| De Koning et al., 2023 [18] | Holland | Retrospective cohort study | Prediction of acute coronary syndrome | Prehospital care, ED |

| Zaboli et al., 2024 [19] | Italy | Observational study | Triage code assessment | ED |

| Gu et al., 2024 [20] | USA | Observational study | High-pressure injuries | ICU |

| Horgn et al., 2017 [21] | Israel | Retrospective, observational cohort study | Sepsis | ED |

| Ivanov et al., 2021 [22] | USA | Retrospective study | Triage level: emergency severity index | ED |

| Cramer et al., 2019 [23] | Israel | Observational study | Prevention of pressure ulcers | ICU |

| Greenbaum et al., 2019 [24] | not reported | Retrospective cohort before-and-after study design and qualitative study | Prediction of presenting problems in emergency department | ED |

| Yu et al., 2020 [25] | Korea | Retrospective study | Prediction of adverse clinical outcome (mortality in the emergency department or intensive care unit admission) | ED |

| Tsumoto et al., 2006 [26] | Japan | Observational study | Prediction of adverse events | ED |

| Lee et al., 2018 [27] | Korea | Observational study | Prevention of unplanned extubation | ICU |

| Wang et al., 2023 [28] | Taiwan | Retrospective cohort study | Prediction of delirium | ICU |

| King et al., 2023 [29] | USA | Retrospective cohort study | Integration of evidence-based practices in rounding teams | ICU |

| Chang et al., 2019 [30] | USA | Observational study | Prediction of critical vital signs | ICU |

| Bhattacharyya et al., 2022 [31] | USA | Observational study | Delirium prediction | ICU |

| Xu et al., 2022 [32] | China | Retrospective cohort study | Prediction of pressure injury | ICU |

| Ladios-Martin et al., 2020 [33] | Spain | Retrospective study and sequential prospective study | Prediction of pressure injury | ICU |

| Toledo et al., 2024 [34] | Brazil | Observational study | Bed bath time | ICU |

| Cui & Jin, 2023 [35] | China | Observational study | Prediction of pressure injury | ICU |

| Brandao-de-Resende et al., 2023 [36] | UK, Brazil | Retrospective study | Triage level | ED |

| Cho et al., 2022 [37] | Korea | Prospective interventional study | Triage | ED |

| Author and Year | Training Model Technique(s) | Techniques of AI | Performance’s Measure(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Abraham et al., 2023 [14] | Gradient-boosted tree model | Machine learning | Accuracy Predicted risk |

| Meyfroidt et al., 2011 [15] | Gaussian Processes (GP) | Machine learning | AUC-ROC Brier score Hosmer–Lemeshow u-statistic Loss penalty function Root mean square relative error |

| Mutegeki et al., 2023 [16] | Decision tree classifier Random forest classifier XGBoost Hist gradient boosting | Machine learning Machine learning Machine learning Machine learning | Precision Accuracy F-1 score AUC |

| Nazzal et al., 2020 [17] | Naive bayes Generalized linear model Logistic regression Fast large margin Deep learning Decision tree classifier Random forest classifier Gradient-boosted trees Support vector machine | Machine learning Machine learning Classic model Deep learning Machine learning Machine learning Machine learning Machine learning Machine learning | Accuracy Precision Sensitivity Specificity Processing time (min) |

| De Koning et al., 2023 [18] | Support vector machine Random forest classifier K-nearest neighbor Logistic regression | Machine learning Machine learning Machine learning Machine learning | Sensitivity Specificity Negative predictive value Positive predictive value Precision F-beta score |

| Zaboli et al., 2024 [19] | ChatGPT | Large Language Model | Sensitivity Specificity Negative predictive value Positive predictive value AUC-ROC Unweighted Cohen’s kappa |

| Gu et al., 2024 [20] | Logistic regression XGBoost | Classic model Machine learning | Accuracy AUC Precision Sensitivity F-1 score |

| Horgn et al., 2017 [21] | Support vector machine Logistic regression Naive bayes Random forest | Machine learning Classic model Machine learning Machine learning | AUC-ROC Sensitivity Specificity Positive predictive value |

| Ivanov et al., 2021 [22] | XGBoost | Machine learning | Accuracy AUC-ROC F-1 score Precision Sensitivity Under-triage Over-triage |

| Cramer et al., 2019 [23] | Logistic regression Elastic net Support vector machine with a linear kernel Random forest Gradient boosting machine Feed-forward neural network with a single hidden layer | Classic model Machine learning Machine learning Machine learning Machine learning Deep learning | Precision Sensitivity |

| Greenbaum et al., 2019 [24] | Support vector machine | Machine learning | Structured data capture Completeness Precision Overall quality Mean keystrokes required |

| Yu et al., 2020 [25] | Logistic regression Deep learning with R package “keras” Random forest | Classic model Deep learning Machine learning | AUC-ROC |

| Tsumoto et al., 2006 [26] | Decision tree classifier | Machine learning | Number of events |

| Lee et al., 2018 [27] | Logistic regression (nearest value) Logistic regression (nearest value, recording frequency) Logistic regression (nearest value; recording frequency; minimum, maximum, and mean with highest effect size) | Classic model Classic model Classic model | AUC-ROC Sensitivity Specificity Positive predictive value Negative predictive value |

| Wang et al., 2023 [28] | Logistic regression Gradient-boosted tree Deep learning | Classic model Machine learning Deep learning | AUC-ROC Sensitivity Precision Specificity Brier score Calibration plot |

| King et al., 2023 [29] | Regression model | Classic model | Positive predictive value Sensitivity Negative predictive value Specificity |

| Chang et al., 2019 [30] | Random forest XGBoost Artificial neural net Recurrent neural network—Long short-term memory network | Machine learning Machine learning Deep learning Deep learning | Heart rate AUC-ROC Blood oxygen level AUC-ROC Mean arterial pressure AUC-ROC Respiratory rate AUC-ROC Systolic blood pressure AUC-ROC |

| Bhattacharyya et al., 2022 [31] | Logistic regression Random forest Bidirectional long short-term memory | Classic model Machine learning Deep learning | AUC-ROC AUPRC Sensitivity Brier score |

| Xu et al., 2022 [32] | Logistic regression Decision tree Random forest | Classic model Machine learning Machine learning | AUC-ROC Sensitivity Specificity Accuracy Precision Positive predictive value Negative predictive value F-1 score |

| Ladios-Martin et al., 2020 [33] | Averaged perception Bayes point machine Decision tree Boosted decision forest Decision jungle Locally deep support vector machine Logistic regression Neural network Support vector machine | Machine learning Machine learning Machine learning Machine learning Machine learning Machine learning Classic model Deep learning Machine learning | AUC-ROC Sensitivity Specificity Accuracy Positive predictive value Negative predictive value |

| Toledo et al., 2024 [34] | Perceptron neural network 1 Perceptron neural network 2 Neural network with radial basis function Decision tree Random forest | Deep learning Deep learning Deep learning Machine learning Machine learning | R square Root mean square error Mean absolute error |

| Cui & Jin, 2023 [35] | Bidirectional long short-term memory Recurrent neural network Gated recurrent units Long short-term memory Random forest Logistic regression | Deep learning Deep learning Machine learning Machine learning Machine learning Classic model | F-1 score Precision Sensitivity AUC-ROC |

| Brandao-de-Resende et al., 2023 [36] | Logistic regression Decision tree Random forest XGBoost | Classic model Machine learning Machine learning Machine learning | Sensitivity Specificity |

| Cho et al., 2022 [37] | Neural network | Deep learning | Time for triage Intraclass correlation coefficient |

| Author(s) | Type of Data Used by AI | Input Data | Output Data |

|---|---|---|---|

| Abraham et al., 2023 [14] | Vitals Clinical notes | Structured data (continuous data) Unstructured data | Continuous data |

| Meyfroidt et al., 2011 [15] | Vitals Admission data (patient history and preoperative medical condition) Medication data Laboratory data Physiological data (urine output, ventilator, blood loss) | Structured data (continuous data) Unstructured data | Continuous data |

| Mutegeki et al., 2023 [16] | Vitals Demographical data Triage variables Disposition Chief patient complaint Past medical history Laboratory data Medication data Imaging data Historical usage statistics | Structured data (continuous, binary, categorical) Unstructured data | Categorical data |

| Nazzal et al., 2020 [17] | Vitals Demographical data Laboratory data Past medical history Medication data Admission data Discharge data | Structured data (continuous, binary, categorical) Unstructured data | Categorical data |

| De Koning et al., 2023 [18] | Vitals Demographical data Triage variables Past medical history Medication data ECG’s description Physical examination Symptoms | Structured data (continuous data) Unstructured data | Binary data |

| Zaboli et al., 2024 [19] | Vitals Demographical data Triage code Past medical history | Structured data (continuous, categorical) Unstructured data | Categorical data |

| Gu et al., 2024 [20] | Nursing notes | Unstructured data | Binary data, text |

| Horgn et al., 2017 [21] | Vitals Demographical data Chief complaint Nursing notes Acuity level | Structured data (continuous, binary, categorical) Unstructured data | Binary data |

| Ivanov et al., 2021 [22] | Vitals Demographical data Past medical history Chief complaint Nursing notes | Structured data (continuous, categorical) Unstructured data | Categorical data |

| Cramer et al., 2019 [23] | Vitals Demographical data Admission data Laboratory data Comorbidities Ventilation status | Structured data (continuous, categorical data) | Categorical data |

| Greenbaum et al., 2019 [24] | Vitals Demographical data Nursing notes | Structured data (continuous, categorical data) | Categorical data |

| Yu et al., 2020 [25] | Vitals Demographical data Admission data | Structured data (continuous, binary, categorical data) | Categorical data |

| Tsumoto et al., 2006 [26] | Type of near miss Patient factors Medical staff factors Shift information | Structured data (continuous, categorical data) Unstructured data | Continuous data |

| Lee et al., 2018 [27] | Vitals Demographical data Ventilation status Nurses’ notes | Structured data (continuous, categorical data) Unstructured data | Categorical data |

| Wang et al., 2023 [28] | Vitals Demographical data Medication data Laboratory data Comorbidities Glasgow coma scale | Structured data (continuous, binary, categorical data) | Continuous data |

| King et al., 2023 [29] | Rounding teams’ recordings | Unstructured data (audio) | Text |

| Chang et al., 2019 [30] | Vitals Demographical data Laboratory data Medication data Mortality | Structured data (continuous, categorical, binary data) | Continuous data |

| Bhattacharyya et al., 2022 [31] | Vitals Demographical data Laboratory data Medication data Ventilation status Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score | Structured data (continuous, categorical data) Unstructured data | Continuous data |

| Xu et al., 2022 [32] | Age Comorbidities Surgical history Ventilation status Glasgow coma scale | Structured data (continuous, binary, categorical data) | Categorical data |

| Ladios-Martin et al., 2020 [33] | Demographical data Mobility Care process Medication data Laboratory data Mental status Surgical history Skin status Nutrition | Structured data (continuous, categorical data) Unstructured data | Categorical data |

| Toledo et al., 2024 [34] | Demographical data Bed bath time Comorbidities Medication data Devices Oxygen therapy | Structured data (continuous, binary data) | Continuous data |

| Cui & Jin, 2023 [35] | Vitals Laboratory data Braden scale-related features Glasgow Coma Scale Overall patient condition | Structured data (continuous, categorical data) Unstructured data | Categorical data |

| Brandao-de-Resende et al., 2023 [36] | Demographical data History of presenting illness Medical history Signs and symptoms | Structured data (continuous, binary data) Unstructured data | Categorical data |

| Cho et al., 2022 [37] | Vitals Chief concern Medical history Allergies | Unstructured data (voice) | Text |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Porcellato, E.; Lanera, C.; Ocagli, H.; Danielis, M. Exploring Applications of Artificial Intelligence in Critical Care Nursing: A Systematic Review. Nurs. Rep. 2025, 15, 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15020055

Porcellato E, Lanera C, Ocagli H, Danielis M. Exploring Applications of Artificial Intelligence in Critical Care Nursing: A Systematic Review. Nursing Reports. 2025; 15(2):55. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15020055

Chicago/Turabian StylePorcellato, Elena, Corrado Lanera, Honoria Ocagli, and Matteo Danielis. 2025. "Exploring Applications of Artificial Intelligence in Critical Care Nursing: A Systematic Review" Nursing Reports 15, no. 2: 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15020055

APA StylePorcellato, E., Lanera, C., Ocagli, H., & Danielis, M. (2025). Exploring Applications of Artificial Intelligence in Critical Care Nursing: A Systematic Review. Nursing Reports, 15(2), 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15020055